archives for 06/2010

We've been eating broccoli for a week, but the crop

finally reached critical mass Monday. Perhaps a third of the

plants had heads at full maturity --- if I left them any later, they'd

start to degrade. So I picked a basketful...

...and

put over a gallon away for the winter.

...and

put over a gallon away for the winter.Last fall, I cut the tops off our broccoli and let the plants send out side florets for a couple of months, but I manage spring broccoli quite differently. With my spring crop, I cut down the whole plant when I harvest the top, peeling the stems to be added to the steamer pot.

Part of the reason for this different management is pests. As we reach June, the few, easily-picked cabbage worms are joined by the southern cabbageworm, which burrows up under the florets and is very difficult to pry out. I figure it's not worthwhile to fight the bugs for a few sideshoots.

I also planted the broccoli a bit too close together this spring, so it's good to thin the crop and give the smaller plants room to grow. Once the little guys mature, I want to hurry and put in a different summer crop in the broccoli beds while it still has time to grow. Finally, I just really love the taste of broccoli stalks!

While I was at it, I froze 5 pints of spinach, collards, and swiss chard. I've resolved that we will not have to resort to buying vegetables next March and April!

The

primary reason for the mixed reports on comfrey's efficacy stems from a

confusion of terms. Even after reading the entire chapter in

Hills' Russian Comfrey about comfrey species, I had

to do a bit more research to make sure I had the story straight.

The

primary reason for the mixed reports on comfrey's efficacy stems from a

confusion of terms. Even after reading the entire chapter in

Hills' Russian Comfrey about comfrey species, I had

to do a bit more research to make sure I had the story straight.

There appear to be three

comfrey species in cultivation at the moment

(as well as several others growing wild.) The least interesting

from a permaculture point of view is Prickly Comfrey (Symphytum

asperrimum, aka S. asperum.) This comfrey is

easily identified by its sky blue flowers, and is only useful as an

ornamental.

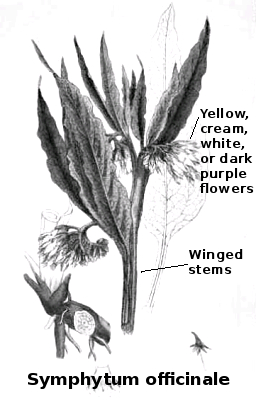

On the other hand,

Common Comfrey (sometimes just called Comfrey, Symphytum

officinale) is

largely cultivated as a

healing herb. The plant usually has winged stems and yellow,

cream, white, or dark purple flowers. Common Comfrey is

relatively easy to confuse with the third species of comfrey, but

yields much less biomass.

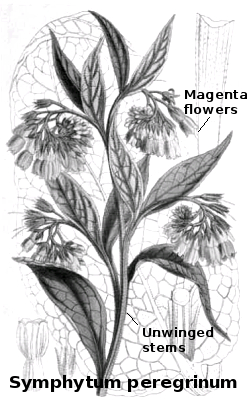

Finally, Russian Comfrey

is the star of the permaculture show. To

make it nice and simple, Russian Comfrey has been known by the

following scientific names: S.

peregrinum, S.

officinale x asperrimum, S.

uplandicum, or S.

asperum x officinale.

To cut through the Latin for you, that means that some folks think

Russian Comfrey is a hybrid between the first two comfrey species I

discussed, while others think it merits species status.

The best Russian

Comfreys --- which may not be all of them --- are very

palatable to livestock, have magenta flowers (or perhaps blue flowers

that fade to pink), and have solid, wingless flower stems.

Russian Comfrey can produce up to 120 tons of plant matter per acre per

year, while Common Comfrey clocks in at about a third that.

Although he didn't write

about it in his book, Lawrence Hills apparently

went on to select a super productive Russian Comfrey now known as

"Bocking 14". Since I'm pretty sure that the comfrey I've been

playing with is merely Common Comfrey, I've put "Bocking 14" on my

plant wish list. Anyone out there have a cutting you can spare?

| This post is part of our Comfrey lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

When we first started using

the large

well pump to supply water to the irrigation sprinklers I was timid

about how long it should be used at one time.

I was concerned that too much

continued pumping might damage the motor, but little by little we kept

using it for longer episodes. Now it's not uncommon to see them going

for hours at a time.

Every now and then a

sprinkler head will get clogged with some creek debris, but it only

takes a minute to unscrew the hose and remove any offending algae or

sand.

What's most challenging is

getting 220 volts from the trailer to the creek. More on that in part 2

of this creek pumping series.

Internet

sources tell me to harvest new potatoes when:

Internet

sources tell me to harvest new potatoes when:

- The potatoes begin to bloom.

- The calendar changes to June.

- The peas are ripe.

I noticed the first

flowers on our potato plants this weekend, so I decided to dig around

and see what's there. The result? The potatoes are past the

tiny new potato stage I love, and are already swelling into the

half-fist-size zone. I guess option 3 is the best indicator for

my garden since the peas have been ripe for a week or two, which is

just about when I should have harvested new potatoes.

Most

people harvest new potatoes by grubbing them out from around the bases

of plants, leaving some tubers in place to finish growing. I

opted to just yank out two plants since they were encroaching on my

biggest tomato's growing zone. This gave me a great opportunity

to explore the benefits of my modified

Ruth Stout method,

and I'm totally sold on the heavy mulch. The potatoes required

just a little digging with the trake, but they came out clean and

beautiful, with nary a spot of green. The area is also nearly

weed-free despite never being weeded (though I did toss a few more

handfuls of grass clippings on insipient weeds a few weeks ago.)

Most

people harvest new potatoes by grubbing them out from around the bases

of plants, leaving some tubers in place to finish growing. I

opted to just yank out two plants since they were encroaching on my

biggest tomato's growing zone. This gave me a great opportunity

to explore the benefits of my modified

Ruth Stout method,

and I'm totally sold on the heavy mulch. The potatoes required

just a little digging with the trake, but they came out clean and

beautiful, with nary a spot of green. The area is also nearly

weed-free despite never being weeded (though I did toss a few more

handfuls of grass clippings on insipient weeds a few weeks ago.)

I picked a bowlful of

our stunning sugar snap and snow peas, cut up the first basil leaves of

the year, and added the rest of the ingredients for a modified Green Bean and

Potato Salad.

The taste of summer!

The

traditional farm use for comfrey has

been as livestock food. Once dried, comfrey contains up to 26%

crude protein, along with an assortment of minerals sucked from the

subsoil by eight foot deep roots. In addition, comfrey contains

less fiber than grass does (10.9% of dry weight), which makes it a good

feed for non-ruminants like pigs and chickens that have a hard time

digesting fiber. Anecdotal evidence exists for feeding comfrey to

horses, cows, donkeys, sheep, goats, chickens, and pigs, and at the

time Lawrence

Hills wrote his book (the early 1950s), race horses were being fed

comfrey as a way of keeping the animals in top condition.

The

traditional farm use for comfrey has

been as livestock food. Once dried, comfrey contains up to 26%

crude protein, along with an assortment of minerals sucked from the

subsoil by eight foot deep roots. In addition, comfrey contains

less fiber than grass does (10.9% of dry weight), which makes it a good

feed for non-ruminants like pigs and chickens that have a hard time

digesting fiber. Anecdotal evidence exists for feeding comfrey to

horses, cows, donkeys, sheep, goats, chickens, and pigs, and at the

time Lawrence

Hills wrote his book (the early 1950s), race horses were being fed

comfrey as a way of keeping the animals in top condition.

The question is --- how

much of these animals' traditional diets can be replaced by

comfrey? Little data existed at the time Hills' book was written,

but he suggested several hypotheses based on information about various

animals' known nutritional needs and a few on-the-ground trials.

One farmer noted that providing pigs unlimited comfrey allows you to

lower their storebought feed by 50%, and another farmer used the exact

same figures with his two horses. Comfrey can be used to replace

up to 10% of chickens' feed without lowering egg yield (though chickens

are the most sensitive to excess roughage of all the livestock

mentioned, so you might not want to go much higher than that.)

Lawrence suggests slowly increasing the proportion of comfrey included

in an animal's diet until signs of negative effects are noted.

When I first heard that

chickens eat comfrey, I got excited and tossed some in the

tractor...and my girls looked at me like I was crazy. Hills says

that most livestock will learn to like comfrey, but not in the fresh

form. The prickly hairs that make me use gloves when harvesting

can't be pleasant in an animal's mouth, but luckily the prickles are

merely a thin layer of silica stiffened with water. If you cut

the leaves and wilt them for a day or so, animals can eat the comfrey

with no ill effects --- I'll have to give that a shot! Other

farmers cut comfrey to make hay for the winter, or even turn goats and

sheep (who don't mind the prickles) onto a pasture of comfrey in the

spring and fall when grass pasture quality is at its worst.

If you're considering

comfrey as animal feed, you should cut your comfrey often so that it

never sends up flower stalks (like those shown in the second

image.) The percentages listed in this post are all for comfrey

in the leafy stage, while flower stalks have nearly double the fiber

and less than half the protein.

Have you tried feeding

comfrey to your animals? What did you think?

| This post is part of our Comfrey lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

When we first started this irrigation

project the budget was a bit limited.

I'm sure it breaks every law

of proper electric wiring, but sometimes you've got to do what you've

got to do.

It's basically four 100 foot extension cords cobbled together and wired

so each pole is carrying 110 volts. I'm pretty sure this is close to

the maximum distance you should think about stretching these cords.

Electrical tape works well for sealing up the junctions where each cord

is plugged into.

We're going on the third year

of this setup. There was a problem in the

beginning with the pump connections, but I solved that by figuring out

how to make the contact points waterproof.

If you feel like you're

testing the limits of safety try picking up the

cord in question to see if it's giving off much heat while you have

your pump working. It's this heat

that can be dangerous and must be dealt with by making the distance

shorter or the electrical cord thicker.

Mark and I are thinking

of printing up some Walden Effect t-shirts roughly based on a

petroglyph, but tweaked to more closely resemble our farm. Poll

time!

Mark and I are thinking

of printing up some Walden Effect t-shirts roughly based on a

petroglyph, but tweaked to more closely resemble our farm. Poll

time!

Even if you hate

t-shirts, please vote in the first poll so that we can get an idea of

the size of our readers. We want to make sure to have the right

sizes on hand for giveaways.

What

size t-shirt do you

wear most frequently?

Are

you interested in

buying this t-shirt (somewhere in the $10 to $15 range)?

Do you like this t-shirt

design?

Would you be interested

in a t-shirt larger than XL even though it costs about $5 more?

Thanks! Once we

get an idea for sizes and quantity, we'll figure out a price --- our

cost plus shipping --- and will put in an order.

Hills

boldly states that no other

plant will produce as much biomass for composting when grow in an out

of the way corner as comfrey. In addition, comfrey is a

much-lauded dynamic

accumulator, able to

stretch its roots deep into the

subsoil and draw up calcium, potassium, phosphorus, and trace minerals

that are out of reach of most other plants. Finally, comfrey's

C:N ratio is so low that it nearly

melts into the soil, creating

compost in next to no time. What's not to like?

Hills

boldly states that no other

plant will produce as much biomass for composting when grow in an out

of the way corner as comfrey. In addition, comfrey is a

much-lauded dynamic

accumulator, able to

stretch its roots deep into the

subsoil and draw up calcium, potassium, phosphorus, and trace minerals

that are out of reach of most other plants. Finally, comfrey's

C:N ratio is so low that it nearly

melts into the soil, creating

compost in next to no time. What's not to like?

When growing comfrey as

the raw material for compost, Hills recommends

taking six to eight cuttings between April and November. If

you're using a highly productive Russian Comfrey variety, you can

produce 100 or more tons of leaves per acre in this manner, and you

could

potentially double or triple that yield in heavily fertilized patches

on a small scale. The plants are cut two inches above the ground

when they are between one and three feet tall, allowed to dry for 48

hours to lower their moisture content, then gathered and

added to the compost pile.

An alternative use of comfrey as a fertility

plant is found in forest

gardening literature, which suggests planting

comfrey below fruit

trees as a sort of

living mulch. Last year, I tried this out, planting comfrey

around the

base of our nectarine, and now I'm cutting the comfrey every week or

two, allowing the leaves to drop down and produce a heavy mulch and

then compost around the tree's trunk.

An alternative use of comfrey as a fertility

plant is found in forest

gardening literature, which suggests planting

comfrey below fruit

trees as a sort of

living mulch. Last year, I tried this out, planting comfrey

around the

base of our nectarine, and now I'm cutting the comfrey every week or

two, allowing the leaves to drop down and produce a heavy mulch and

then compost around the tree's trunk.

On the positive side, I've

noticed that the under-tree area requires nearly no weeding, but I feel

like the comfrey may be competing with the tree more than it's giving

back with my frequent cuttings --- the nectarine's leaves aren't as

vibrantly green as the leaves of our two peach trees.

Unfortunately, I have no other nectarines to compare mine to, so the

data is very inconclusive. However, Hills agrees with my gut

reaction, noting that comfrey will steal potassium from fruit trees and

requires more nitrogen than the tree can handle well. I'm going

to keep searching for some other literature to the contrary, but for

now I'm thinking I would probably be better off planting comfrey beyond

the tree's spread and cutting the leaves to drop around my tree's base.

| This post is part of our Comfrey lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Having a mother hen

cooped up with a baby chick

presents a small adjustment issue for the Avian Aqua Miser that is

easily resolved with a booster step.

I prefer the look of

something natural like this piece of firewood that Lucy has long since carried away and gnawed.

Weeding

may be a boring job, but it has its perks. While ripping up big

weeds in the upper raspberry patch, Mark came across this tiny box

turtle. Ten minutes later, he found another! I guess our

berry patch has the box turtle seal of approval.

Weeding

may be a boring job, but it has its perks. While ripping up big

weeds in the upper raspberry patch, Mark came across this tiny box

turtle. Ten minutes later, he found another! I guess our

berry patch has the box turtle seal of approval.

I have to admit that I'm

a bad, bad farmer. A good farmer would move the box turtles out

of the area since they like to eat strawberries and tomatoes.

Instead, I carefully relocated the pair to the shade under the worm bin and gave them a strawberry

apiece. What can I say --- finding a hatchling box turtle has

been my life-long dream.

Hopefully

you're sold by now and can think of at least one use for comfrey on your homestead. So

how do you grow it?

Hopefully

you're sold by now and can think of at least one use for comfrey on your homestead. So

how do you grow it?

Choose

a good location.

Comfrey isn't picky about soil quality, but it requires deep soil with

no hardpan, rock layer, or high water table to prevent the roots from

reaching

deep. Heavy clay is no problem, and is in fact preferred.

Although comfrey is moderately shade tolerant, it will be less

productive when planted out of the sun.

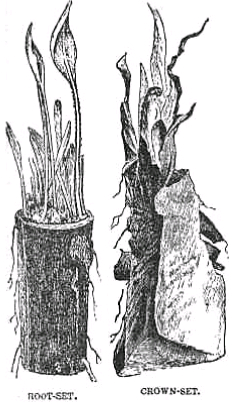

Propagate

your plants.

Comfrey is only grown from cuttings, so unless your pockets are deep

you will want to buy a few plants and then divide them up. The

good news is that one good-sized comfrey plant can be divided into

dozens of small plants, many of which can be harvested starting the

first

year. First dig up the large plant and cut off sections near the

top containing leaves --- each leaf crown area can become its own

plant. Then take all of the small roots that are left, cut them

into one inch sections, and plant them in a nursery bed one inch deep

and two inches apart. These youngsters can be transplanted into

permanent locations the next spring.

Prepare your ground.

Comfrey will outcompete almost anything once it gets a foothold, but

you could lose your crop to weeds while it's getting established.

So take a bit of time to root out any perennial weeds.

Prepare your ground.

Comfrey will outcompete almost anything once it gets a foothold, but

you could lose your crop to weeds while it's getting established.

So take a bit of time to root out any perennial weeds.

Plant

your comfrey.

Comfrey needs a permanent location, much like an orchard, since it's

very difficult to eradicate once comfrey has gained a foothold on a

plot of

ground. Space plants three feet apart in good soil, or half that

in poor soil. Plant in the fall (September to November) or spring

(March to May.)

Weed and

fertilize.

One tantilizing system consists of planting comfrey in the chicken

run. Since chickens don't like unwilted comfrey leaves, the birds

will weed

between the comfrey and fertilize it in the process, only requiring you

to add wood ashes or another form of potassium every few years to

balance the fertility. You can cut a plant or two every day while

feeding your chickens, and the poultry will eat up the cuttings the

next day once they're wilted. If you're not using chickens, dig

out any perennial weeds by hand and fertilize annually.

Weed and

fertilize.

One tantilizing system consists of planting comfrey in the chicken

run. Since chickens don't like unwilted comfrey leaves, the birds

will weed

between the comfrey and fertilize it in the process, only requiring you

to add wood ashes or another form of potassium every few years to

balance the fertility. You can cut a plant or two every day while

feeding your chickens, and the poultry will eat up the cuttings the

next day once they're wilted. If you're not using chickens, dig

out any perennial weeds by hand and fertilize annually.

Harvest. You can begin

cutting leaves as early as the first year, but the plants produce the

maximum yield

starting in the third year. After several more years,

productivity will

begin to decline as the centers of the huge comfrey plants die

out. This is the point at which you'll want to dig up the plants

and divide them, or just turn in pigs to root out the comfrey and start

a new comfrey patch elsewhere.

| This post is part of our Comfrey lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The flock block is

wearing down to more of a bowl shape.

It seems to be a good value compared to the 50 pound bags of feed due

to what I think is an increase in protein.

Let's

look at a contest between the six beds of shelling peas I planted in

early March and the six beds of broccoli I transplanted in early

April. This week, I've harvested about a quarter of the shelling

peas, and about two thirds of the broccoli, freezing all of the peas

and most of the broccoli. Elapsed harvest and freezing

time? Half an hour for the peas, an hour and a half for the

broccoli.

Let's

look at a contest between the six beds of shelling peas I planted in

early March and the six beds of broccoli I transplanted in early

April. This week, I've harvested about a quarter of the shelling

peas, and about two thirds of the broccoli, freezing all of the peas

and most of the broccoli. Elapsed harvest and freezing

time? Half an hour for the peas, an hour and a half for the

broccoli.

So far the two crops

seem to be about even, right? Now let's look at how much food

we've gotten out of those beds --- one cup for the peas, two gallons for the broccoli. When

you look at the food produced per hour harvest time, that's like the

difference between being paid $2.50 per hour and $50 per hour --- I

know which one I'd choose.

Granted, peas do have a

lot going for them in other ways. They provide protein for our

bodies, and also fix nitrogen to feed the soil. They freeze well

(but so does the broccoli) and are finished in time for me to plant a

summer crop (though broccoli wins here, coming out a precious week or

two earlier.) We find them tasty and easy to cook with, too, but

no more so than broccoli.

This is the fourth year

we've grown shelling peas, and each year I was certain the problem was

the pea variety. Having run through four different varieties now,

I'm ready to accept that maybe shelling peas aren't the best crop for

our farm. Our snow and sugar snap peas seem to produce about four

times as much plant matter per bed, but we can't really grow more of

them since we only like them fresh. Maybe we'll skip the shelling

peas next year and double up on broccoli instead?

In fact, we could have

tripled our broccoli planting since I still have five empty beds that

are waiting to be filled with the other half of our sweet potato slips,

slowly budding in the sun room. Why maintain empty beds all

spring when they could be feeding us broccoli?

I'm not suggesting we

actually get $50 worth of food per hour with the broccoli. I

didn't count in the planting, transplanting, weeding, and watering

time, and I actually have no clue how much frozen broccoli costs in the

store.

Did we really need the extra Trake?

Yes...the Trake is one of

those garden instruments that when backed up with a twin can become

twice the tool if you've got the extra hands to wield them.

I've

been known to tell prospective apiarists that bee stings don't

hurt. "It's about like getting a shot," I tell them. "You

feel it for a minute, but pretty soon you've forgotten it even

happened." Friday, I learned that I was lying.

I've

been known to tell prospective apiarists that bee stings don't

hurt. "It's about like getting a shot," I tell them. "You

feel it for a minute, but pretty soon you've forgotten it even

happened." Friday, I learned that I was lying.

I've been going into the

hives every week lately, trying to keep the brood boxes open while the

bees try to fill them with honey in preparation for an eventual swarm

that I'm determined won't happen. Last week, I added a second

brood box on one of the hives, checkerboarding empty frames and full

frames so that the hive now had two half empty brood boxes rather than

one mostly full one. I wanted to see how that experiment was

working out, but when I opened the hive all I saw was honey.

We've barely had any

rain in the last few weeks, so I shouldn't have been too surprised to

see that two supers were chock full of mostly or completely capped

honey. I carefully removed two frames for extraction, and paged

through the other frames to make sure the queen hadn't moved up to lay

in the supers. So far so good --- all twenty frames were brood

free. But there was just so much honey that I accidentally nicked

a couple of frames, and sweet, gooey honey dripped down through the

hive.

Maybe the open honey got

the bees' dander up, or more likely the bees sensed the first few

clouds converging and the dropping barometric pressure that forecast a

storm moving into our neighborhood. All I know is that halfway

through my inspection of the top brood box, a bee stung me on the

arm. Whatever --- no big deal. But I know that when one bee

stings, the other bees can smell it and I should close up the

hive. Unfortunately, a sting also jars me out of my "bee zone"

--- a zen-like state where I move slowly and the bees barely know I'm

there. I started to close the hive too quickly and the second

sting came, then the third.

Those of you who've been

following along at home have probably noticed that I wear a pretty

tight shirt when checking on the hive. It shouldn't be that tight

since having cloth appressed to skin makes it easy for a bee to sting

through, but it's the only light-weight, non-button-up, long-sleeved

shirt I own (a wardrobe choice that is soon to be remedied.)

Anyway, the bees were mad, and they made straight for the big things

bulging out at them, which unfortunately happened to be a very

sensitive portion of my anatomy. Ten stings later, the hive was

closed, and I was nearly in tears.

Once

I calmed back down and did a bit of research, I discovered that --- as

usual when I get stung --- I was doing several things wrong. As

soon as I noticed the first clouds gathering, I should have packed

everything up and gone home. Secondly, I should have stuck to

either checking on the brood box or robbing honey, not both.

Finally, when I did get stung, I should have immediately left the hive, puffed a little

smoke on the wound, and given both the bees and myself a couple of

minutes to calm down. I suspect if I'd taken that first sting as

a warning, brought myself back to the bee zone, and closed up the hive

slowly, all would have been well. I certainly don't want to leave

any potential beekeepers thinking that the hive is a dangerous place,

but it is quite easy to get stupid, especially as a newbie.

Once

I calmed back down and did a bit of research, I discovered that --- as

usual when I get stung --- I was doing several things wrong. As

soon as I noticed the first clouds gathering, I should have packed

everything up and gone home. Secondly, I should have stuck to

either checking on the brood box or robbing honey, not both.

Finally, when I did get stung, I should have immediately left the hive, puffed a little

smoke on the wound, and given both the bees and myself a couple of

minutes to calm down. I suspect if I'd taken that first sting as

a warning, brought myself back to the bee zone, and closed up the hive

slowly, all would have been well. I certainly don't want to leave

any potential beekeepers thinking that the hive is a dangerous place,

but it is quite easy to get stupid, especially as a newbie.

One final note: Although

the bees clearly won that round, as you'll see in my next post, the

ending was sweet....

The first do

it yourself pet door lasted a few months before the screen

broke free. Not a good choice of material.

I found some see through

material that is working out much better once I installed a layer on

each side.

It got Huckleberry's meow of

approval, but Strider is still reserving judgment due to his fear of

change.

Although

I was running toward the trailer at top speed and swatting at my

breasts, I still had

the presence of mind to grab those two full frames

of honey. My beekeeping mentor (aka movie star neighbor)

had admonished me that, at this time of year, the frames need to go

back on

the hive ASAP. Within a couple of hours, he warned, bees will

start building comb willie nillie to fill that empty space. So,

even though I mostly felt like crawling into bed, I needed to extract

our honey and open the mean hive back up.

Although

I was running toward the trailer at top speed and swatting at my

breasts, I still had

the presence of mind to grab those two full frames

of honey. My beekeeping mentor (aka movie star neighbor)

had admonished me that, at this time of year, the frames need to go

back on

the hive ASAP. Within a couple of hours, he warned, bees will

start building comb willie nillie to fill that empty space. So,

even though I mostly felt like crawling into bed, I needed to extract

our honey and open the mean hive back up.

I iced my wounds, but my

head wasn't quite on

straight when I got to work on the honey. In fact, this post

really should be called "how to do everything wrong while extracting

honey." I hope you'll learn by seeing

the error of my ways.

Step

1: Remove the bees from the honey.

I actually managed to do this step well, moving the frames a good

distance from the hives (which calmed the bees down),

then gently brushing one frame at a time free of bees.

Step

2: Uncap the honey.

Here's where I failed miserably. For future reference, a plain

kitchen knife will mangle your comb so that it falls apart in the

extractor. A bread knife works great.

Step

3: Extract the comb honey. Place the cappings in a

collander on top of a bowl and mash the wax with a spoon to let the

honey begin to drain out.

Step 4: Place a bowl under the spout at the

bottom of the extractor. With the state my head

was in, I'm surprised I remembered this step.

Step 4: Place a bowl under the spout at the

bottom of the extractor. With the state my head

was in, I'm surprised I remembered this step.

Step

5: Extract.

Place

the frames in the extractor opposite each other so that they are

balanced. With new comb like ours, it's best to gently spin the

extractor a few times, then flip the frames around and fully empty out

the other side of each frame, before flipping the frames a second time

and giving the handle a few hard spins. My beekeeping mentor

explained

this to me in great detail, but when I tried the gentle spin, I

couldn't see honey coming out (even though it was), so I spun

harder. As a result, the comb on my mangled frame from step 2

fell apart, and even the other frame got a bit distorted.

Step 6: Cut out the mangled frame to join the

cappings.

Oops.

Step 6: Cut out the mangled frame to join the

cappings.

Oops.

Step

7: Put the frames back on the

angry, angry hive, along with an extra super since the bees are clearly

making honey faster than we can extract it. Your hive won't be

angry. Mine was because I made a mistake.

Step

8: Pour the honey from under the collander and from under the extractor

into canning jars for storage. No need to can ---

honey will keep indefinitely if harvested when fully capped and stored

in an  air-tight container.

Some people strain the honey first to remove the little bits of wax,

but I didn't bother.

air-tight container.

Some people strain the honey first to remove the little bits of wax,

but I didn't bother.

Step

9: Taste a bit of honey. It was all worth it!

I'm actually glad I

tried a couple of frames before embarking on a larger extracting

expedition. Now I'll know what I'm doing this week when we remove

a gallon (!!!) from the hive.

Several

friends of mine have neither the inclination, time, nor space to grow

their own vegetables, so they join a CSA

to be part of the local food

system. Inevitably, a few weeks in, they regret the

decision. "What do I do with a huge basket of mixed greens?" they

moan. Or, "Five butternut squash? I

don't know how to cook squash!"

Several

friends of mine have neither the inclination, time, nor space to grow

their own vegetables, so they join a CSA

to be part of the local food

system. Inevitably, a few weeks in, they regret the

decision. "What do I do with a huge basket of mixed greens?" they

moan. Or, "Five butternut squash? I

don't know how to cook squash!"

The truth is that the

beginning gardener often feels the same

way. We're used to buying whatever vegetables suit our fancy or

are mandated by our favorite recipes, and we don't know how to make a

salad when we realize that lettuce and tomatoes are never in season at

the same time. On a similar note, we might want to start a

garden, but we don't know which vegetables are within our reach and

which ones are the domain of experienced green thumbs. How can we

even start when the whole endeavor looks so daunting? It's much

easier to pick up some organic produce at the grocery store and figure

we're doing our part to save the world.

Although I know that

many of our readers are long time gardeners and

cooks who use in-season produce without thinking about it, I also

suspect that others of

you are afraid to put the first plants in the ground because you just

don't know how to go from seed to gourmet feast. This week's

lunchtime series launches a new facet of this blog geared toward giving

beginners the information they need to start a quick and easy garden

and then to enjoy the bounty. I hope that you experienced

gardeners and

foodies will read along and add your own advice on which plants are

easy to grow in your neck of the woods, and on simple recipes you use

to produce delicious, in-season meals.

| This post is part of our Beginner's Guide to Gardening and Eating in

Season lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

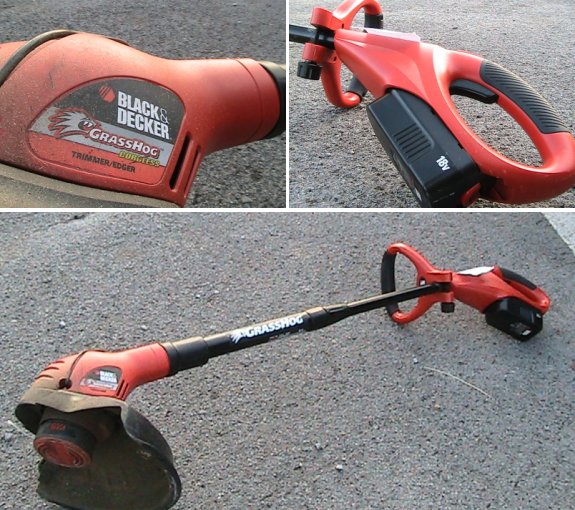

I

picked my beekeeping mentor's brains this weekend, and decided to go

ahead and harvest

a lot more honey out

of the overflowing hive. My mentor told me that when he harvests

honey, he takes the super off the hive, closes the hive back up, turns

the super on its side on top of the hive, and blasts the bees out with

a leaf blower. Wow!

I

picked my beekeeping mentor's brains this weekend, and decided to go

ahead and harvest

a lot more honey out

of the overflowing hive. My mentor told me that when he harvests

honey, he takes the super off the hive, closes the hive back up, turns

the super on its side on top of the hive, and blasts the bees out with

a leaf blower. Wow!

I was a bit too scared

to do that (and don't have a leaf blower), so I tried the same method I

used last week, carrying the frames around to the other side of the

trailer to confuse the guard bees, then brushing off the frames one at

a time. Since I took two whole supers off the hive this time,

though, rather than just a couple of frames, the method didn't work so

well. There were gobs of bees present, and when I brushed them

loose, they flew around the front door in a writhing (and not very

amused) mass.

No major stings

resulted, but I had once again riled up the hive. They began to

harass Mark in the garden so much that he had to come inside, and when

my cousin-in-law stumbled in from the yurt, he was a bit surprised to

be divebombed on his way through the door.

Apparently I'm still

making basic beginner mistakes. Next time, I'll try brushing the

bees off near the hive so that they can head home quickly. It

also turned out that only five of the frames were fully capped, so I

probably would have been better off picking frames out of the hive

rather than disrupting so many workers' lives. Still, no harm

done, and we've now harvested about five and a half quarts of honey.

I still haven't even

opened up the most productive hive, though. Maybe in a few days

once my poor cousin-in-law flees the farm.

The

easiest way to lose the gardening bug permanently is to start a huge

garden with a bunch of vegetable varieties suited only to an expert,

then see everything disappear down insect gullets in a few

months. I recommend that beginning gardeners instead start small,

with just a few vegetables that are nearly impossible to kill.

Here are my top contenders:

The

easiest way to lose the gardening bug permanently is to start a huge

garden with a bunch of vegetable varieties suited only to an expert,

then see everything disappear down insect gullets in a few

months. I recommend that beginning gardeners instead start small,

with just a few vegetables that are nearly impossible to kill.

Here are my top contenders:

Leaf

lettuce - The

time has

already passed for this cool season crop, but fall will be here before

you know it. Lettuce is great for beginners because you can't do

anything wrong and you get to harvest a month after planting. One

of the easiest to grow in our area is Black-seeded Simpson, but I like

to mix in a red variety for eye candy. Read all of my tips

on growing lettuce here.

Swiss chard - Most greens are

extremely easy, but Swiss chard takes the cake. Unlike other

greens, swiss chard doesn't get bitter, nor does it bolt the first

year. The greens are mild in flavor and can be substituted in

recipes which call for spinach (a vegetable that does bolt quite

quickly.) Although they taste the same as the white-stalked

variety, urban gardeners will love Swiss chard varieties with leaf

stalks ranging in color from white to yellow to red since they're

pretty enough to mix into your flower border. This warm season

crop should be planted after your frost-free date ---

for nearly all of you, that means you can go ahead and plant now.

Once

the leaves are four inches tall, I start cutting them just like leaf

lettuce once or twice a week, making sure I don't cut the growing bud,

but taking most other leaves.

Swiss chard - Most greens are

extremely easy, but Swiss chard takes the cake. Unlike other

greens, swiss chard doesn't get bitter, nor does it bolt the first

year. The greens are mild in flavor and can be substituted in

recipes which call for spinach (a vegetable that does bolt quite

quickly.) Although they taste the same as the white-stalked

variety, urban gardeners will love Swiss chard varieties with leaf

stalks ranging in color from white to yellow to red since they're

pretty enough to mix into your flower border. This warm season

crop should be planted after your frost-free date ---

for nearly all of you, that means you can go ahead and plant now.

Once

the leaves are four inches tall, I start cutting them just like leaf

lettuce once or twice a week, making sure I don't cut the growing bud,

but taking most other leaves.

Tomatoes - In my opinion,

tomatoes are really a year two crop, but the flavor difference between

a homegrown tomato and a storebought one is so great that few people

can resist planting them. For the raw beginner, you should go

ahead and buy a transplant or two from the feed store and put them out

after the frost-free date. Choose a slicer or a tommy-toe (or

both). Be sure to cage or stake your tomato, and if you're

starting this year, I

highly recommend pruning since the blight is still in the air. In

later

years, I think you'll be happier starting your own tomatoes from seed

and growing primarily romas for ease of storage, but in year one you

should stick to simple vegetables that go straight on your plate.

Tomatoes - In my opinion,

tomatoes are really a year two crop, but the flavor difference between

a homegrown tomato and a storebought one is so great that few people

can resist planting them. For the raw beginner, you should go

ahead and buy a transplant or two from the feed store and put them out

after the frost-free date. Choose a slicer or a tommy-toe (or

both). Be sure to cage or stake your tomato, and if you're

starting this year, I

highly recommend pruning since the blight is still in the air. In

later

years, I think you'll be happier starting your own tomatoes from seed

and growing primarily romas for ease of storage, but in year one you

should stick to simple vegetables that go straight on your plate.

Basil - I see people buy basil

transplants, and I can't figure out why. Basil is the easiest

herb you can grow --- throw the seeds on the ground around your

frost-free date and you'll be picking off leaves a couple of weeks

later. The trick to a summer-long harvest is to cut your basil

back regularly (at least once a week) and never let it bloom.

With lettuce and swiss chard, I told you to be careful not to harvest

the central growing bud, but with basil I advocate the reverse.

Cut the whole top off the plant, leaving one or two pairs of older

leaves at the base, and it will branch out into a bush. Keep

cutting the youngest, tastiest leaves, and your plant will just get

bigger and bushier. When the basil does start trying to bloom,

pick off the flower buds. I recommend a simple Sweet Italian or

Genovese basil for your first year, but later you can branch out into

the varieties that taste great in other ethnic foods.

Sweet Corn - The only major

thing that can go wrong with corn is lack of pollination if you plant

too small of an area. I try to plant at least two short rows

together, and three or four are better. Your corn will mature

nearly all at once, so for a full summer harvest, I plant a bed on our

frost-free date, and continue planting another bed every two weeks

until the end of June. Like tomatoes, there's no comparison

between homegrown and storebought sweet corn. But this is the one

vegetable where I like to stick with fancy hybrids --- heirloom

varieties are starchy instead of sweet.

Sweet Corn - The only major

thing that can go wrong with corn is lack of pollination if you plant

too small of an area. I try to plant at least two short rows

together, and three or four are better. Your corn will mature

nearly all at once, so for a full summer harvest, I plant a bed on our

frost-free date, and continue planting another bed every two weeks

until the end of June. Like tomatoes, there's no comparison

between homegrown and storebought sweet corn. But this is the one

vegetable where I like to stick with fancy hybrids --- heirloom

varieties are starchy instead of sweet.

Okra - Okra may seem like an

odd choice for the beginner, but in the South few crops beat its ease

of growth. In fact, the plant has such huge, beautiful flowers

that okra can easily pass for an ornamental. Plant the seeds at

the frost-free date, and in a couple of months you'll see blooms and

little, furry fruits. Cut the whole fruit off at the stem when it

is less than three inches long and steam it --- the trick to defeating

okra slime is to never let water touch the interior of the fruit.

We eat our steamed okra with our fingers, holding it by the stem and

eating the fruit portion off, but you could cut the tops off after

steaming them if you like. The traditional method of eating okra

is to slice, batter, and fry it, but I can't really recommend that

approach. Our favorite variety is Clemson Spineless.

The beginner should pick

two to four of these varieties to try out their first year,

steering clear of okra if you live in the north and of tomatoes if you

live in a very hot area like Texas. Plant a very small garden, no

more than perhaps 100 feet square, and mulch the whole thing if

possible to cut down on weeding. If you have anther choice, steer

clear of pots, which are harder than they look, and keep good records

of when and where you planted and what happened. Most of you

still have time to start something this year, so go do it!

| This post is part of our Beginner's Guide to Gardening and Eating in

Season lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I only made it 2 weeks before

I hit another fatal stump with the mower which took out the new

flywheel shaft key that

was installed recently.

This time I used a different

guy who was a lot closer and 3 bucks cheaper. I was all ready with a

long screw driver/pry bar and mini-sledge to try to do the operation

myself, but once I started taking it all apart I realized the first guy

tightened down some of the nuts too tight. I remember him using an air

wrench, and not seeing a torque wrench being applied. Most experts

think they can gauge it by feel, but this nut was on so tight I broke

2 sockets trying to get it off.

The moral of this story is to

make sure your nuts don't get over tightened.

If

you ask ten gardeners the best way to manage tomatoes, you'll get

twenty answers. We've tried out a different method every year,

and still haven't found one we're truly happy with. This year

we're using out the old standby --- one stake per plant, then prune to

three main stems.

If

you ask ten gardeners the best way to manage tomatoes, you'll get

twenty answers. We've tried out a different method every year,

and still haven't found one we're truly happy with. This year

we're using out the old standby --- one stake per plant, then prune to

three main stems.

The Master Gardeners of

Santa Clara County have a very comprehensive page about the advantages

and disadvantages of different tomato support methods. They note that the

one stake method results in less productive plants, which is the reason

I've steered clear of pruning in the past.

On the other hand, the

tomato blight is still in the air this year across the eastern U.S.,

and I'm willing to accept a lower yield if I actually get something. Pruning does have the

advantage of keeping the plant drier, which means that fungi don't have

the humid environment they need to thrive. Here's hoping that

drastic pruning and other blight

prevention will give

us a crop.

If

you take my advice and plant a few of the easy vegetables

mentioned in

my last post, you will quickly be overrun with fresh produce. Now

what do you do with it?

If

you take my advice and plant a few of the easy vegetables

mentioned in

my last post, you will quickly be overrun with fresh produce. Now

what do you do with it?

First of all, it's

essential that you get over the grocery store

mentality that a slight blemish means a vegetable gets tossed in the

trash. Your vegetables may have a bug nibble here and there, or

even a crack in the side. Don't worry about it. I can't for

the life of me find a link, but I was recently told about a sect of

monks who were quite healthy vegans until they began to buy commercial

produce and came down with nutritional deficiencies. It turned

out that the insects they were accidentally ingesting in their previous

diet of non-commercial vegetables had been keeping them healthy.

I don't wash our homegrown produce, and we find it delicious, bugs,

dirt, blemishes, and all.

Chances

are, once you discover how good your homegrown vegetables

taste, a good amount of the bounty won't even make it out of the

garden. Eventually, you'll probably want to present the

vegetables as part of the meal, which is the purpose of this

post. Tomorrow I'll

give you pointers on becoming a bit fancier.

Chances

are, once you discover how good your homegrown vegetables

taste, a good amount of the bounty won't even make it out of the

garden. Eventually, you'll probably want to present the

vegetables as part of the meal, which is the purpose of this

post. Tomorrow I'll

give you pointers on becoming a bit fancier.

Lettuce - By the time fresh

tomatoes and cucumbers reach my plate, lettuce is long gone, which

blows my traditional salad out the window. Here are some in-season salad ideas.

Swiss

chard - The

easiest way

to prepare stellar greens is to cut them into bite-size pieces and

steam them for a few minutes until the stems are soft. Drizzle

them with balsamic vinegar and eat. Once you get bored with that,

try sauteing the greens in a large pot in a bit of oil, adding minced

garlic for the last minute of cooking.

Tomatoes - Once you get sick of just

eating tomato slices (if ever), try our cucumber and tomato salad. Some people add goat

cheese and/or mozarella to the mix for a heartier salad.

Basil - Pesto is the obvious

solution to an overdose of basil. I've posted my recipe for chestnut pesto, but we usually use walnuts

in our daily lives. Pine nuts are the classic pesto component,

but are extremely pricey.

Basil - Pesto is the obvious

solution to an overdose of basil. I've posted my recipe for chestnut pesto, but we usually use walnuts

in our daily lives. Pine nuts are the classic pesto component,

but are extremely pricey.

Sweet

corn - In my

opinion, the

only way to eat sweet corn is to very lightly cook it. Bring a

big pot of water to a boil while you shuck the corn, then drop the ears

in for less than a minute, just until they change color.

Carefully pull them out with a pair of tongs and eat immediately (with

salt and/or butter if you prefer.)

Okra - I already mentioned that I

prefer steaming okra, and that most people fry it. What's your

favorite way to eat okra?

Whatever you do,

remember that freshness is key. As soon as you

pick an ear of corn, the sugars begin to turn to starches and the

flavor declines. Although the difference isn't quite as

pronounced with other vegetables, the trend is the same. For

maximum flavor and nutrition, pick produce right before eating it.

| This post is part of our Beginner's Guide to Gardening and Eating in

Season lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I was all set to get a

Craftsman 24 inch pry bar/flywheel remover when I found this one for

only 4.99

at Harbor Freight.

Usually the Craftsman no

questions lifetime warranty is enough to push me into spending more for

a tool, but in this case I think I'll be okay with the cheaper

model....especially when it also has a lifetime warranty at a third of

the price.

It says Pittsburgh, but it's

made in Taiwan and it feels heavy duty. Stay tuned to see how it handles

some real world pressure when I replace my first flywheel

shaft key in hopefully what will be far in the future.

If

the beginner

recipes in my last

post look boring to you, you're

probably ready to become an experimental, in-season chef. Most

cookbooks are chock full of fascinating recipes...which call for

ingredients from three different seasons per dish. Here are my

intermediate tips for learning to cook in season.

If

the beginner

recipes in my last

post look boring to you, you're

probably ready to become an experimental, in-season chef. Most

cookbooks are chock full of fascinating recipes...which call for

ingredients from three different seasons per dish. Here are my

intermediate tips for learning to cook in season.

First, start with the

ingredients. Rather than saying, "I feel

like lasagna tonight," take a look in the garden and see what's

ripe. Our recipes at the moment revolve around snow and sugar

snap peas, new potatoes, eggs, broccoli, greens, basil, and parsley,

which is why we've been making meals like pesto pasta with balsamic

vinegared greens and a fried egg on the side.

Once

you know what you're cooking with, head to one of the recipe

websites like epicurious and type your

ingredients into the search

box. The website will spit out a whole string of recipes for you

to choose between.

Once

you know what you're cooking with, head to one of the recipe

websites like epicurious and type your

ingredients into the search

box. The website will spit out a whole string of recipes for you

to choose between.

Chances are, you still

won't have all of the ingredients required by a

recipe, so you should be willing to substitute for a more appropriate,

in-season vegetable or herb. Some of my favorite replacement

plants are Egyptian onions for leeks and parsley for celery since I can

harvest Egyptian onions and parsley for at least 11 months out of the

year.

Finally, some vegetables

are such good keepers that they can be

considered to almost always be in season. Bulb onions, potatoes,

garlic, and carrots are a few examples. You can add them to your

recipes with impunity.

| This post is part of our Beginner's Guide to Gardening and Eating in

Season lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The

Jackson Titanium Xtra is hands down the best shovel I've ever moved

dirt with.

The

Jackson Titanium Xtra is hands down the best shovel I've ever moved

dirt with.

The soft rubberized grip makes it easy to hold, but what sold me was

the power step feature, which increases leverage by allowing your foot

and legs to do more of the work.

It costs over twice what a cheaper shovel goes for, but well worth it

in my opinion.

The squash vine

borer will be

hitting our farm shortly --- I know because the first brilliant flowers

have come out on the summer squash. With the impending collapse

of our plants looming, I've resolved to find a better solution than

Bt. Bacillus

thuringiensis is

rated organic but is still a relatively broad spectrum insecticide,

which means it may be doing more harm than good by killing beneficials

that would otherwise wipe out the borer. In addition, try as we

might to spray once a week and after rains, Bt doesn't seem to be

preventing the total destruction of our summer squash crop each

year. We're both willing to do without summer squash for a year

or two, if need be, while we figure out a better option.

The squash vine

borer will be

hitting our farm shortly --- I know because the first brilliant flowers

have come out on the summer squash. With the impending collapse

of our plants looming, I've resolved to find a better solution than

Bt. Bacillus

thuringiensis is

rated organic but is still a relatively broad spectrum insecticide,

which means it may be doing more harm than good by killing beneficials

that would otherwise wipe out the borer. In addition, try as we

might to spray once a week and after rains, Bt doesn't seem to be

preventing the total destruction of our summer squash crop each

year. We're both willing to do without summer squash for a year

or two, if need be, while we figure out a better option.

This year, we're keeping

our experiments simple. I'm planting a new bed of summer squash

every two weeks to give me an idea of the timing of the

infestation. In the north, you can just plant your summer

squashes late, after the fourth of July, and the vine borer  will

have finished its flying stage. In the south, though, the vine

borer has multiple generations, so I'm not sure how early I can plant

squash and still miss the insect's depradations. A planting at

the beginning of August 2009 netted us a bounty of summer squash...for

about two weeks before the frost hit. I'm hoping to be able to

plant a bit earlier than that and still miss the borer.

will

have finished its flying stage. In the south, though, the vine

borer has multiple generations, so I'm not sure how early I can plant

squash and still miss the insect's depradations. A planting at

the beginning of August 2009 netted us a bounty of summer squash...for

about two weeks before the frost hit. I'm hoping to be able to

plant a bit earlier than that and still miss the borer.

Other options to try in

later years if the easy route fails include:

- Planting a more resistant summer squash variety such as Summer

Crookneck

- Using a floating row cover over the plants to physically exclude attack

- Wrapping something around the stem (panty hose and aluminum foil

have both been used) to keep the larvae out

- Mounding up dirt over the stem at intervals to promote rooting

(which would require a different squash variety since we've been

planting bush squash)

This

week's lunchtime series has barely scratched the surface of learning to

start a small garden and eat the fruits of your labor. If you

catch the bug, you're sure to want to learn more. Of course,

you'll keep reading our blog, but where else should you turn?

This

week's lunchtime series has barely scratched the surface of learning to

start a small garden and eat the fruits of your labor. If you

catch the bug, you're sure to want to learn more. Of course,

you'll keep reading our blog, but where else should you turn?

Barbara Kingsolver's Animal,

Vegetable, Miracle

may help to get you inspired, and also includes some in-season

recipes. For more solid information about

growing your food, many beginners report getting a lot out of Square Foot

Gardening,

despite its flaws. The basic spacing, planting, and harvesting

information about all vegetables can be found on extension service

websites using a quick google search. (I've found keyword

combinations like "tomato cultivation" get good results.)

Year one is a good time

to start learning about the soil food web, and Teaming

With Microbes

is a quick, fun way to open your eyes to what's going on beneath the

surface. I don't have specific books to recommend, but other

important topics to consider include composting and

beneficial insects.

Finally, why not take a

master gardener class? Most state

extension services now offer these semester-long classes for a small

fee. You'll meet other gardeners in your area and will come away

with a great grounding in basic concepts.

Whatever you do, don't

put the process off until next year. If all you have the time and

energy for is throwing one tomato plant in the ground, do it!

Right this instant! Turn off your computer, pick up your trowel,

and plant!

| This post is part of our Beginner's Guide to Gardening and Eating in

Season lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I've decided these plastic hose repair kits are better than the metal

ones.

It's easier to install, and

most importantly won't snag on every other thing that comes by.

I know the metal might stand

the test of time better, but this is some hard plastic, and I'll do

almost anything to prevent any more entanglement with the mower.

The

current small subset of the forest pasture has finally been mostly

denuded. In

preparation for switching the cockerels over to the larger paddock

(where the weeds are now waist-high), I opened the dividing gate and

let the mother hen and her chick mingle with the flock.

The

current small subset of the forest pasture has finally been mostly

denuded. In

preparation for switching the cockerels over to the larger paddock

(where the weeds are now waist-high), I opened the dividing gate and

let the mother hen and her chick mingle with the flock.

I was a bit concerned

that the lone chick

would be no match for 25 mostly grown cockerels, but I needn't have

worried. When I went in to feed the combined flock Friday

morning, the cockerels stampeded me and even rushed out the door.

Were they starving? Nope. They were just terrified of Mama

Hen, who was walking behind them.

All

the mother hen has to do is glare in their general direction and 25

teenage males scatter in terror. How's that for a matriarch?

All

the mother hen has to do is glare in their general direction and 25

teenage males scatter in terror. How's that for a matriarch?

On a semi-related note,

next week we'll be slaughtering our first round of cockerels. If

you're not ready to see that part of the life cycle, you have now been

forewarned.

Was that a Snap

On magnetic, ratcheting, screwdriver I saw in yesterday's

picture of the plastic hose repair kit?

Kevin, Carlsbad,

CA.

You've got a keen eye for

quality.

Yes, It's one of the few

tools I still have from my copier repair days of the 1990s.

The handle is hollow and can

be used to store spare bits, but what I like most is the magnetic tip

and long reach. The additional leverage combined with the ratcheting

feature make this screwdriver in my opinion the best money can buy.

It's got a steep price of 67

bucks, but somehow I justified it by using it 5 days a week as the main

tool that began each copier operation. Could I have gotten by with a

cheaper one? Sure, but one stripped screw in a hard to reach place can

really ruin your day and once I started applying the added leverage the

days of stripped screws were long gone.

Two

weeks ago, I pinched off the tops of the

black raspberry canes. Left to their own devices, black raspberry

primocanes will grow so long they bend down and root a new plant at

their tip. This trait is useful if you're looking to expand your

berry patch, but is less useful if you actually want to be able to get

into the patch to pick berries.

Two

weeks ago, I pinched off the tops of the

black raspberry canes. Left to their own devices, black raspberry

primocanes will grow so long they bend down and root a new plant at

their tip. This trait is useful if you're looking to expand your

berry patch, but is less useful if you actually want to be able to get

into the patch to pick berries.

If you choose to keep

your plants contained, you can pinch off the tips

when the brambles reach waist high. In most plants, apical

dominance tells the plant to put all of its energy into growing the

main shoot, but if that main shoot is gone, the side buds are allowed

to grow. The bottom photo shows what one plant looks like two

weeks after pinching. Notice how the side shoots have grown out

--- these will all be coated with fruits next year when the primocane

becomes a floricane.

I've

similarly pruned our cultivated

blackberries.

Blackberries usually aren't tip-rooters, but

mine are, and I've also found that they will grow primocanes a dozen

feet long if left to their own devices. I prefer the plants to

stay contained in my obsessive rows, so I take a few minutes to summer

prune.

I've

similarly pruned our cultivated

blackberries.

Blackberries usually aren't tip-rooters, but

mine are, and I've also found that they will grow primocanes a dozen

feet long if left to their own devices. I prefer the plants to

stay contained in my obsessive rows, so I take a few minutes to summer

prune.

Common

wisdom (perhaps apocryphally) holds that children were originally sent

home from school for three months of working on the farm in the

summer. Although we're child-free by choice, I wouldn't mind a

few extra field hands at this time of year.

Common

wisdom (perhaps apocryphally) holds that children were originally sent

home from school for three months of working on the farm in the

summer. Although we're child-free by choice, I wouldn't mind a

few extra field hands at this time of year.

June is the overlap zone

between spring and summer, when we're harvesting honey, chickens,

broccoli, peas, and greens as fast as we can, but are also nurturing

the summer crops in preparation for the main event. Meanwhile,

we're starting to plant the first of the fall crops in beds freed up by

the spring bounty, and Mark's mowing his heart out, trying to stay

ahead of the grass.

In the winter, I

literally can't remember the tastes, scents, and sights of June.

The days are so long, the garden and woods so green, that I wake up at

dawn ready to get to work. Garden tasks feel urgent --- we both

know how easy it would be to lose all of our hard work in just a few

weeks of getting behind on the weeding.

When the sun finally sets

around 9:30, lightning bugs drifting through the garden and tree frogs

calling from the floodplain, my eyelids are drooping. We're

currently subscribed to one netflix at a time, and I can't remember the

last time I actually made it through the movie before falling asleep.

When the sun finally sets

around 9:30, lightning bugs drifting through the garden and tree frogs

calling from the floodplain, my eyelids are drooping. We're

currently subscribed to one netflix at a time, and I can't remember the

last time I actually made it through the movie before falling asleep.

Which is all a long way

of saying --- our lunchtime series will be going on summer vacation

starting this week. Look for a return to deep thoughts in a few

months when I want to dream of the garden again, rather than live in

it. (There may be a series thrown in here and there if I just

can't resist, though, so don't get your hopes up too high.)

This is what's called a 6

person bed weeder.

I like the idea of always

having a shade cover that follows you around and it seems like it has

to be easier on the back than the old standard method.

Afternoon siestas must be

mandatory when you have such a shady place to lay down at after lunch?

Mark

dug the rest of the garlic on Monday and hung it under the eaves to

dry. I can honestly tell you that there's more garlic beside our

front door than I've ever seen in one spot in my life!

Mark

dug the rest of the garlic on Monday and hung it under the eaves to

dry. I can honestly tell you that there's more garlic beside our

front door than I've ever seen in one spot in my life!

Learning from last

year's drying fiasco, we hung up the garlic in

small clumps immediately after digging. This photo shows some of last

week's garlic ---

notice how it's already drying up nicely due to the air movement around

the exposed bulbs and leaves. If we had room indoors, we could

also have spread the plants out in a single layer on screens to dry.

Either way, the bulbs

will be thoroughly cured and ready to move to storage two weeks after

harvest. At that point, the garlic will have sucked all of the

nutrients out of the leaves and roots, so it's safe to cut off the

excess plant material. We store our garlic in mesh bags we save

from buying winter oranges.

Last

year's garlic is still lingering on our kitchen shelf, proving that it

is quite possible to eat your own garlic for an entire year without any

special storage area. The trick for preventing your garlic from

sprouting is counter-intuitive --- keep it warm. Once garlic has

been cooled and then re-warmed, the plant thinks it has survived a

winter and starts to grow. Keep the heads warm (but not hot) and

they'll linger in an eternal summer.

Last

year's garlic is still lingering on our kitchen shelf, proving that it

is quite possible to eat your own garlic for an entire year without any

special storage area. The trick for preventing your garlic from

sprouting is counter-intuitive --- keep it warm. Once garlic has

been cooled and then re-warmed, the plant thinks it has survived a

winter and starts to grow. Keep the heads warm (but not hot) and

they'll linger in an eternal summer.

One last note on garlic

curing and storing --- be sure to pull out the biggest heads for next

year's planting. I'm pretty sure that the few small heads mixed

in with our many large heads were due to me not being vigilant enough

about planting only the biggest cloves from the biggest heads last

fall. Even though you might want to brag by giving away those

beautiful big heads to your friends and family, just think how much

more you'll get to brag next year when every one of your garlic heads

is that size!

These

new dark

cornish chickens we've been pasturing are said to be more predator

resistant than most birds.

These

new dark

cornish chickens we've been pasturing are said to be more predator

resistant than most birds.

We've yet to see any signs of

predator trouble thanks to Lucy and the new K9

electric fence strand.

What predator resistant

really means for this operation is a substantial increase in the

challenge to catch your bird when it's time to process.

It gets easier with practice,

but I think we'll experiment with a different breed next time.

We

dispatched

the first third of our cockerels Tuesday morning. They

were quite small at 12 weeks old, dressing out to only 2.25 pounds

apiece (not counting the necks and giblets), and they clearly don't

compete with grocery store prices at $5.64 per bird. Of course,

we didn't set out to save money with these broilers or we would have

stuck to the traditional Cornish

Cross. The

real test will be

flavor --- can we tell a difference between our pastured chickens and

storebought?

We

dispatched

the first third of our cockerels Tuesday morning. They

were quite small at 12 weeks old, dressing out to only 2.25 pounds

apiece (not counting the necks and giblets), and they clearly don't

compete with grocery store prices at $5.64 per bird. Of course,

we didn't set out to save money with these broilers or we would have

stuck to the traditional Cornish

Cross. The

real test will be

flavor --- can we tell a difference between our pastured chickens and

storebought?

We're going to kill

another third of the cockerels in a month, and then

the last third at 16 weeks old, testing to see how the price per pound

and the flavor of the meat changes over time. Although everyone

is in agreement that Cornish Crosses should be

killed at around eight weeks, the internet lists widely

varying

maturity dates for the Dark Cornish, and I like experimentation.

On the other hand,

despite enjoying the experiment, I don't think we'll

be raising Dark Cornish again. They didn't live up to the hype of

being good foragers --- they mostly sat around and waited for their

feed, even going so far as to run away when I tossed grubs into their

pasture. Instead, I'm torn between several alternatives:

- Cornish Cross --- This is

the traditional way to go, but raising these grain-only-eating broilers

at home is little better for the environment and our bodies than buying

grocery store meat. Also, since they're hybrids, we would have to

buy chicks every year, which doesn't pass the sustainability test.

- Freedom Rangers --- Many small growers swear by this breed, reporting that Freedom Rangers are good foragers (although they said that about Dark Cornish too.) The major downside is that we couldn't create our own breeding flock since Freedom Rangers are a cross of carefully bred parental lines owned by European corporations.

- Create our own Cornish cross

--- We could save back the biggest cockerel and cross him with our

Plymouth Rocks to create our own Cornish

Cross. We might get hybrid vigor, but I can't quite see where the

foraging ability would come from, and I'm bound and determined to grow

chickens without such large inputs of grain.

- Eat the roosters from our layer

flock

--- Traditionally, farmers used to just raise dual purpose breeds and

eat the roosters from their flock along with the old hens. We've

been well trained to think we want big breasts and tender meat, so

I'm not sure if we could stomach this option. But it would

definitely be the most sustainable, and probably the best for our

health if we stuck to a good forager like Rhode Island Red.

What do you think?

Have you given some of the above options a

shot and think they've got merit (or should be avoided at all

cost?) We won't be raising another batch of broilers until next

year, but we need to make a decision soon about whether to save back

one of the Cornishes from the chopping block.

Things got a bit more crowded for the mother hen and her cute chick

today when I installed a west wing door to the coop.

This allows us to cut off the

previous pasture so we can give it a rest and plant something more

edible than the weed buffet they started off with.

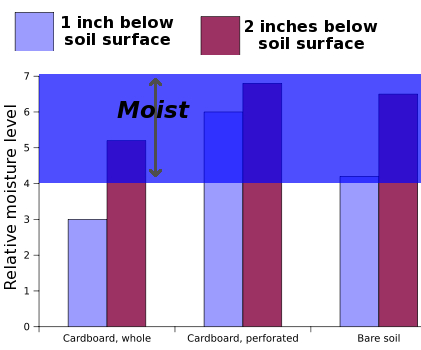

I'm

sure you've all been perched on the edge of your seats for the last

couple of weeks wondering: Will cardboard

mulch retard water

penetration and harm our plants? A couple of days after I posted

about our cardboard mulch, Mark had the great idea of poking a bunch of

holes in the cardboard with a pitchfork. Even so, I was a bit

concerned that the perforated cardboard would keep the soil too dry.

I'm

sure you've all been perched on the edge of your seats for the last

couple of weeks wondering: Will cardboard

mulch retard water

penetration and harm our plants? A couple of days after I posted

about our cardboard mulch, Mark had the great idea of poking a bunch of

holes in the cardboard with a pitchfork. Even so, I was a bit

concerned that the perforated cardboard would keep the soil too dry.

Rather than waiting to see if

our vegetables started

struggling, we

bought a $10 moisture meter from Lowes and took some

measurements. As you can see, the perforated cardboard actually

kept the soil wetter than either whole cardboard or bare soil,

especially in the top inch of the soil. Whole cardboard, on the

other hand, was a loser --- I headed out with the pitchfork to

perforate the overlooked bed right after taking these measurements.

Rather than waiting to see if

our vegetables started

struggling, we

bought a $10 moisture meter from Lowes and took some

measurements. As you can see, the perforated cardboard actually