archives for 01/2011

The woodpile melted

enough that I could stack logs in the shed....

...and the firewood is

already dripping dry.

The snow is melting off

the garden.

The wash water tank is

full again, and Mark's

insulated exit point

clearly works.

Best of all, for the

first time in months, the birds are singing! Happy New Year!

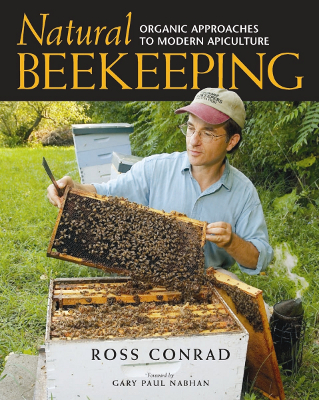

Our

bees took advantage of the recent warm snap to do some house cleaning by

bringing out the dead bees that expired recently.

Our

bees took advantage of the recent warm snap to do some house cleaning by

bringing out the dead bees that expired recently.

Bee keeping sure is easy when

all you have to do is take a few pictures of your wife doing the actual

work and then let the bees do the rest.

Of course I help when it

comes to eating the honey, which makes it a sweet spectator chore that

I recommend to all homesteading husbands out there.

When

Mark

and I got married,

Mark's family kept saying that they wanted to bring a stack cake to our

wedding. We both looked at them in confusion since neither of us

like apple butter, and we instead ended up with the most delicious and

beautiful cake known to man (thanks, Sheila!)

When

Mark

and I got married,

Mark's family kept saying that they wanted to bring a stack cake to our

wedding. We both looked at them in confusion since neither of us

like apple butter, and we instead ended up with the most delicious and

beautiful cake known to man (thanks, Sheila!)

Years later, Mark's mom

sent me the following email, and suddenly the obsession with stack

cakes made sense:

This is the

old apple stack cake, also known as the Appalachian wedding cake.

Years ago, people would come to a wedding and it was a tradition, the

guest would bring one layer of the cake, baked very thin, like with

molasses, ginger, etc. It would  be real dry, could travel without ruin.

Then the hostess would put them all together with apple butter, between

each layer, so the more layers meant that the bride & groom were

that well known.

be real dry, could travel without ruin.

Then the hostess would put them all together with apple butter, between

each layer, so the more layers meant that the bride & groom were

that well known.

This is Mom's favorite cake. I

was able to bake one this year, wanted to share with you how pretty it

came out. I am freezing part of it, so you and Mark can taste

it. Yum yum. This one is 12 layers.

Now that the tradition

has been explained to me, I almost wish we'd gone old-fashioned and had

each of our guests bring a layer to our wedding. Doesn't a stack

cake sound like a fun center-piece for a potluck, but perhaps with

chocolate cakes instead of apple? Or maybe with any cake that

goes well with chocolate frosting?

Thanks for the beautiful

photos and for not minding our cluelessness, Rose Nell! We're

looking forward to tasting such a traditional cake.

A couple of inches of rain

and a lot of melting snow mean that our garden is about as wet as it

gets right now. Still, I was intrigued when I read about pitcher

irrigation. This traditional technique is a bit like drip

irrigation for dummies --- you bury an unglazed ceramic pot in the

soil, fill it with water, and the liquid seeps out into a three to six

foot diameter area, keeping the soil at a constant 80% of

saturation. If the soil gets too wet, water will actually seep

back into the pot, so there's no need to worry about overwatering, and

there is clearly no runoff.

A couple of inches of rain

and a lot of melting snow mean that our garden is about as wet as it

gets right now. Still, I was intrigued when I read about pitcher

irrigation. This traditional technique is a bit like drip

irrigation for dummies --- you bury an unglazed ceramic pot in the

soil, fill it with water, and the liquid seeps out into a three to six

foot diameter area, keeping the soil at a constant 80% of

saturation. If the soil gets too wet, water will actually seep

back into the pot, so there's no need to worry about overwatering, and

there is clearly no runoff.

I've read that 1.5 to

2.5 gallon ceramic pots are ideal, but infonet-biovision suggests using a dried sweet

monkey orange fruit (whatever that is.) Makes me wonder if a

dried gourd would work? I'm very content with our

irrigation method

for the main part of the garden, but would like to have something more

low-tech in my arsenal, especially for watering trees and other

perennials that are spread out across the yard. I can even see

pitcher irrigation being a fun way to keep those potted plants wet

during a dry summer on a hot patio. Has anybody tried it?

After

trying out the kindergarten level of cooking

on the wood stove, I

decided to move on to first grade. Joey gave us this beautiful

Dutch oven after our power outage last year, and it seemed to be the

obvious choice for expanding our culinary arts to roasting a

chicken. I prepared the veggies and chicken as I usually do when roasting in the

electric oven,

settled the fire on a medium-low setting, and then put on the lid of

the Dutch oven.

After

trying out the kindergarten level of cooking

on the wood stove, I

decided to move on to first grade. Joey gave us this beautiful

Dutch oven after our power outage last year, and it seemed to be the

obvious choice for expanding our culinary arts to roasting a

chicken. I prepared the veggies and chicken as I usually do when roasting in the

electric oven,

settled the fire on a medium-low setting, and then put on the lid of

the Dutch oven.

I stirred the vegetables

a few times so that they wouldn't stick to the bottom --- which I

assume is more of a problem in a Dutch oven since the heat comes up

from the bottom --- but I didn't have to baste the chicken at

all. That made this roast chicken a bit lower work than my

oven-roasted chicken, where I try to remember to baste every ten

minutes or so.  On

the other hand, the chicken took about half an hour longer than usual

to cook, and I was glad I had a meat thermometer so that I'd know when

the meat was safely done.

On

the other hand, the chicken took about half an hour longer than usual

to cook, and I was glad I had a meat thermometer so that I'd know when

the meat was safely done.

Our taste test declared

the Dutch oven roasted chicken and vegetables just as good as the

oven-roasted version, but the aesthetics weren't quite as good. I

didn't get the crispy skin I usually end up with and the vegetables

turned into a mush, making me think that I probably should have cooked

the chicken alone for about an hour before adding the root and onion

mixture.

In fact, the Dutch oven

roasted chicken reminded me of the results I've seen from folks who

roast their chicken in a crock pot. That makes me think that

crock pot recipes would be a good place to start when looking for meals

I can cook in the Dutch oven on top of the wood stove.

In

the garden, one of our biggest experiments in 2010 was embarking on the

first stage of experimentation with grain. We tried a do-nothing

oats bed, grew amaranth and quinoa in the vegetable garden, and tried

out buckwheat and oats in the chicken pasture. We learned a lot,

but we still have a long way to go before we achieve grain independence.

In

the garden, one of our biggest experiments in 2010 was embarking on the

first stage of experimentation with grain. We tried a do-nothing

oats bed, grew amaranth and quinoa in the vegetable garden, and tried

out buckwheat and oats in the chicken pasture. We learned a lot,

but we still have a long way to go before we achieve grain independence.

First, I have to admit

that our eating habits changed dramatically in the middle of our grain

experiment, which veered my priorities away from grain. After

extensive research, I decided that we needed to increase the percentage

of protein in our diets. Since I wasn't going to cut back on

fruits and vegetables, that meant reducing our carbohydrates to leave

more room on our plates for beans and meat. Growing oats suddenly

seemed much less important once I stopped eating them for breakfast,

and other grains were similarly sidetracked to the chicken feed

category. But we both felt that the change was a plus since we

started feeling perkier, our brains flowed faster, and we even lost

some weight.

That said, we learned a lot

about growing grains anyway. Our do-nothing

patch (first photo)

wasn't very successful --- leaving the chicken tractor on a patch of

ground for a week in the winter is not enough to kill off the weeds,

and the oats had a lot of competition and ended up patchy and

scrawny. A more effective do-nothing method turned out to be planting

grains in a paddock of the chicken pasture that was scratched bare over

the early summer and then had the last few hardy weeds hoed out

by hand. Of course, growing grains in the vegetable garden

was easy, but seemed like a waste of space since the plants were hardy

enough to put up with the minimal work chicken pasture situation.

That said, we learned a lot

about growing grains anyway. Our do-nothing

patch (first photo)

wasn't very successful --- leaving the chicken tractor on a patch of

ground for a week in the winter is not enough to kill off the weeds,

and the oats had a lot of competition and ended up patchy and

scrawny. A more effective do-nothing method turned out to be planting

grains in a paddock of the chicken pasture that was scratched bare over

the early summer and then had the last few hardy weeds hoed out

by hand. Of course, growing grains in the vegetable garden

was easy, but seemed like a waste of space since the plants were hardy

enough to put up with the minimal work chicken pasture situation.

In terms of variety

selection, the results were once again a mixed bag. I was

intrigued by hullless oats, but in practice found that they were much

more finicky than traditional oats. I can't draw many conclusions

from the failure of hullless oats in the do-nothing patch, but I did

grow side by side hullless and traditional oats as cover crops starting

in August and the former achieved a height of perhaps a third the size

of the latter. I suspect that it's better to just grow

traditional oats and find a way to hull them if you want to eat them

yourselves.

In

the unusual grain category, quinoa

was a flop ---

perhaps I need to try another variety? On the other hand, Manna

de Montana Amaranth was extremely productive, and grew so tall that I

suspect I could grow it in the chicken pasture and let the flock graze

between the plants without worrying about them reaching the

seeds. Amaranth was also very easy to thresh and winnow, although I'm still learning

how to cook it.

In

the unusual grain category, quinoa

was a flop ---

perhaps I need to try another variety? On the other hand, Manna

de Montana Amaranth was extremely productive, and grew so tall that I

suspect I could grow it in the chicken pasture and let the flock graze

between the plants without worrying about them reaching the

seeds. Amaranth was also very easy to thresh and winnow, although I'm still learning

how to cook it.

Back among traditional

grains, we're experimenting with growing

wheat this winter,

but the jury is still out. I have enough data about buckwheat, though, to say that it's a

so-so grain that I probably won't repeat (except as a cover

crop.) Buckwheat did relatively well in the chicken pasture, but

complained about drought --- I think that for maximum yields, I  should

plant it in a part of the garden that gets irrigated. On

the other hand, buckwheat wasn't a fan of the waterlogged soil where I

grew it as a cover crop. The plants also didn't seem to produce

all that much grain, and it would have been tough to pick the

individual seeds if I hadn't just turned the chickens in to eat it

up.

should

plant it in a part of the garden that gets irrigated. On

the other hand, buckwheat wasn't a fan of the waterlogged soil where I

grew it as a cover crop. The plants also didn't seem to produce

all that much grain, and it would have been tough to pick the

individual seeds if I hadn't just turned the chickens in to eat it

up.

Looking toward the

future, our grain patches next year will look very different. The

only grains we eat much of nowadays are a bit of rice and wheat, but

since I can't grow the former I'll be planting wheat and amaranth for

our table. For the chickens, I want to try out millet and field

corn, but will focus more on the high protein sunflower seeds and

perhaps some sort of legume. My hope is that I can continue to

grow our grains in the two chicken pasture paddocks which are on flat

ground, utilizing the chickens to prepare the soil for me and to delete

most weeds.

This post is part of our 2010 experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

1. Leave a 5 gallon

bucket out in the yard to collect rain.

2. Wait for water to freeze.

3. Remove top layer of ice

and position on an old fence post.

After

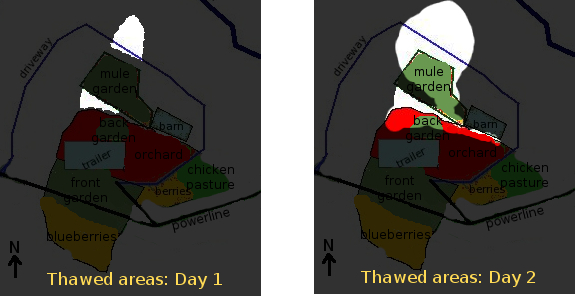

over four years gardening on the same two acres of vegetables, orchard,

and chicken pasture, I'm constantly surprised at how little I know

about the yard's microclimates. As Eliza pointed out on her blog,

snow-melt

is a perfect time to get those microclimates pertaining to sun figured

out --- sunny spots

will be the first to melt while shady spots will keep their snow for

hours or days longer. Our accumulated December snow took days to

melt (tiny bits of it are still out there), so I had a perfect

opportunity to scope out sunny spots day by day.

After

over four years gardening on the same two acres of vegetables, orchard,

and chicken pasture, I'm constantly surprised at how little I know

about the yard's microclimates. As Eliza pointed out on her blog,

snow-melt

is a perfect time to get those microclimates pertaining to sun figured

out --- sunny spots

will be the first to melt while shady spots will keep their snow for

hours or days longer. Our accumulated December snow took days to

melt (tiny bits of it are still out there), so I had a perfect

opportunity to scope out sunny spots day by day.

We live in pretty much

the worst place for gardening in the winter --- on a north-facing slope

on the north side of a hill. As the sun sinks lower into the sky

during the colder months, more and more of the area up against the hill

remains in shadow, and I look with longing at our neighbor's hay field,

across the creek and far enough from the hill that frost on the field  melts

hours before it does in our garden. So I was a bit surprised to

realize that a gap in the hills made an area just beyond the mule

garden melt off even before my neighbor's field did. Doesn't this

look like the absolutely perfect spot for a winter forest pasture? Can't you just

imagine how happy our flock would be, scratching through these leaves,

when their current pasture is still socked in under three inches of

snow and ice?

melts

hours before it does in our garden. So I was a bit surprised to

realize that a gap in the hills made an area just beyond the mule

garden melt off even before my neighbor's field did. Doesn't this

look like the absolutely perfect spot for a winter forest pasture? Can't you just

imagine how happy our flock would be, scratching through these leaves,

when their current pasture is still socked in under three inches of

snow and ice?

Moving

back toward our main yard, I realized that we had another abnormally

sunny spot --- the south-facing side of the gully that divides our mule

garden from our back garden. Seeing the bare soil on this sheer

south face while everything around it was covered with snow made me

realize that I'm leaving a lot of sun on the table by letting this spot

grow up in weeds. Maybe we should put Mark's hobbit cave here

(assuming we could deal with drainage since the bottom of the gully

stays good and damp.) Or perhaps this would be a good spot to

terrace and plant sun-loving something-or-other halfway up the south

face? If we went to all of the work of building a stone wall

behind the terrace, I'll bet we could gain as much as two climate zones

and plant just about anything we want there.

Moving

back toward our main yard, I realized that we had another abnormally

sunny spot --- the south-facing side of the gully that divides our mule

garden from our back garden. Seeing the bare soil on this sheer

south face while everything around it was covered with snow made me

realize that I'm leaving a lot of sun on the table by letting this spot

grow up in weeds. Maybe we should put Mark's hobbit cave here

(assuming we could deal with drainage since the bottom of the gully

stays good and damp.) Or perhaps this would be a good spot to

terrace and plant sun-loving something-or-other halfway up the south

face? If we went to all of the work of building a stone wall

behind the terrace, I'll bet we could gain as much as two climate zones

and plant just about anything we want there.

And

now for the bad news. Since the gully has never been reclaimed

(aka mowed), young trees, briars, and Japanese honeysuckle create a

wall along the south side of the mule garden. Here, in our

sunniest piece of flat ground, I'm wasting an eight foot strip of

growing area along the southern edge due to deep shade from my briar

bushes. We clearly need to find a way to get that gully under

control so that the mule garden will work even better as our sunny

winter garden spot.

And

now for the bad news. Since the gully has never been reclaimed

(aka mowed), young trees, briars, and Japanese honeysuckle create a

wall along the south side of the mule garden. Here, in our

sunniest piece of flat ground, I'm wasting an eight foot strip of

growing area along the southern edge due to deep shade from my briar

bushes. We clearly need to find a way to get that gully under

control so that the mule garden will work even better as our sunny

winter garden spot.

One

of our goals for 2010 was constant mulch cover in the vegetable

garden. We didn't get there, mostly because I got so caught up in

weeding in the middle of the summer that I forgot I could have been

spending half that time mulching and getting the same results.

But we did try out a lot of different mulching materials, discovering

in the process which ones work well for our garden.

One

of our goals for 2010 was constant mulch cover in the vegetable

garden. We didn't get there, mostly because I got so caught up in

weeding in the middle of the summer that I forgot I could have been

spending half that time mulching and getting the same results.

But we did try out a lot of different mulching materials, discovering

in the process which ones work well for our garden.

The easiest and best-suited

mulch (in terms of

C:N ratio and water infiltration) for the vegetable garden is straw, but straw costs an arm and

a leg in our non-grain-growing region. I have high hopes that we

will eventually be growing our own straw as part of our grain

experiments, but in the meantime, I wanted to see which free mulches

would work in its place.

Cardboard showed a lot of promise

early in the season, but ended up keeping the soil too dry. In

the early summer, soil was wetter under the cardboard mulch than in

unmulched areas, but I suspect that was due to the cardboard preventing

evaporation of water that was already in the soil. Even though I

punched holes in the cardboard to promote infiltration of rainwater,

the cardboard-mulched beds started drying out by mid-summer. In

the fall, it was clear that the cardboard-mulched beds were bone dry,

and even our dry-soil-loving peppers started to wilt near the end of

the year. Cardboard seems to be more useful as part of sheet

mulches to delete weeds from new garden areas or from around woody

perennials, and I don't think I'll be using it in the vegetable garden

again.

Cardboard showed a lot of promise

early in the season, but ended up keeping the soil too dry. In

the early summer, soil was wetter under the cardboard mulch than in

unmulched areas, but I suspect that was due to the cardboard preventing

evaporation of water that was already in the soil. Even though I

punched holes in the cardboard to promote infiltration of rainwater,

the cardboard-mulched beds started drying out by mid-summer. In

the fall, it was clear that the cardboard-mulched beds were bone dry,

and even our dry-soil-loving peppers started to wilt near the end of

the year. Cardboard seems to be more useful as part of sheet

mulches to delete weeds from new garden areas or from around woody

perennials, and I don't think I'll be using it in the vegetable garden

again.

Paper was even less

promising. If we subscribed to the newspaper, we probably would

have had better luck, but the junk mail I mulched with had too high of

a percentage of colored dyes and glossiness, and the plants around the

paper mulch mostly died. I'd be curious to see if running the

paper through a shredder first would make it a slightly better mulch by

adding fluffiness and air pockets, but we'll probably use up our junk

mail in the worm bin and perhaps with mushrooms in the future.

Paper was even less

promising. If we subscribed to the newspaper, we probably would

have had better luck, but the junk mail I mulched with had too high of

a percentage of colored dyes and glossiness, and the plants around the

paper mulch mostly died. I'd be curious to see if running the

paper through a shredder first would make it a slightly better mulch by

adding fluffiness and air pockets, but we'll probably use up our junk

mail in the worm bin and perhaps with mushrooms in the future.

We used tree

leaves as a winter mulch on most of the garden last

year, but they were a bit too high in carbon to be optimal for the

vegetable garden. This winter, we're using tree  leaves

as bedding in the chicken coop, where they mix with manure and (I hope)

will turn into a perfect mulch by spring.

leaves

as bedding in the chicken coop, where they mix with manure and (I hope)

will turn into a perfect mulch by spring.

Green leaves --- like grass

clippings, elderberry

leaves, and comfrey

leaves --- are well suited to being used directly on the vegetable

garden as mulch, but each has flaws as well. Elderberry and

comfrey leaves work great, but it feels like the juice isn't worth the

squeeze unless I can find a quicker way of harvesting them, and grass

clippings are really only suitable in the spring before the plants

start to go to seed. I think that this year, I'm only going to

have Mark bag grass clippings for the first month or two, then let the

grass grow up in out of the way parts of the yard in late summer to use

as hay for the chickens.

The

final mulch possibility is wood chips. Well aged wood

chips make the best

mulch for our woody plants, full of beneficial fungi and other soil

microorganisms. I suspect that wood chip mulch that has been well

worked over by the chickens and looks like it's halfway on its path to

becoming stump dirt would also make a perfect mulch for the vegetable

garden since chicken manure would keep this mulch from locking up

nitrogen in the soil. Unfortunately, I rarely have enough really

good (aka homemade) wood chip mulch for the trees and berries, let

alone for the vegetable garden.

The

final mulch possibility is wood chips. Well aged wood

chips make the best

mulch for our woody plants, full of beneficial fungi and other soil

microorganisms. I suspect that wood chip mulch that has been well

worked over by the chickens and looks like it's halfway on its path to

becoming stump dirt would also make a perfect mulch for the vegetable

garden since chicken manure would keep this mulch from locking up

nitrogen in the soil. Unfortunately, I rarely have enough really

good (aka homemade) wood chip mulch for the trees and berries, let

alone for the vegetable garden.

In 2011, we'll probably

continue to buy quite a bit of straw for the garden, but we'll

supplement it in the spring with grass clippings and with the deep

bedding from the chicken coop. In the long run, someday I'd like

to be making enough compost (from cafeteria food scraps?) and wood chip

mulch to keep the garden happy with entirely homemade mulches.

This post is part of our 2010 experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

I've been experimenting

with one of these L.E.D. night lights to see if it can function as a

low budget deer deterrent that shows motion during vulnerable night

hours.

It only took a few minutes to

wrap electrical tape around the cracks to make it water proof and

mounting was even easier as shown in the image above.

A little sensor knows when

the sun goes down and begins projecting different colored light

patterns on the side of the barn, which will hopefully appear as

human/hunter movement to any potential night nibblers.

Worm bin

experiment 2011 is

gearing up. Our new shredder came in the mail yesterday --- the

Fellows PS-60. As usual, I over-researched the decision, but was

glad I did. Most of the shredders on the market today are

cross-cut or confetti shredders, made to turn your paper into pieces

too small for your nosy neighbors to read. However, the whole

point of a shredder for me is to get long strips that won't mat down

quickly in the worm bin, so I kept hunting until I found what's called

a "strip-cut" model. Mark talked me into choosing a shredder in

the $100 price range since he figures the ones half that price will

break down much faster.

Worm bin

experiment 2011 is

gearing up. Our new shredder came in the mail yesterday --- the

Fellows PS-60. As usual, I over-researched the decision, but was

glad I did. Most of the shredders on the market today are

cross-cut or confetti shredders, made to turn your paper into pieces

too small for your nosy neighbors to read. However, the whole

point of a shredder for me is to get long strips that won't mat down

quickly in the worm bin, so I kept hunting until I found what's called

a "strip-cut" model. Mark talked me into choosing a shredder in

the $100 price range since he figures the ones half that price will

break down much faster.

I pulled her out of the

box, sorted my paper into glossy and unglossy, and let her rip.

Junk mail is suddenly a joy! The Fellows shredder will take

twelve sheets of normal paper at a time, which means I could feed

unopened envelopes, big hanks of catalogs, and even the thin cardboard

that tea bags come in through with no trouble. Flattened toilet

paper center rolls were too much for her, but you can just turn the

switch to reverse if you overdo it and your paper will come right back

out.

Meanwhile, I've talked

it over with my non-profit, and they're on board for

being the public face of asking the local school for their food

scraps. I hope that with a non-profit behind me, I won't look

quite so much like a kook. My letter to the principal is going in

the mail this week. Wish me luck!

Cover

crops were another innovation in 2010, doing double-duty as weed

suppressors and compost creators. My first goal was to find

varieties that like our clay soil and work well with no-till conditions

in zone 6 (i.e. they die over the winter or are easy to kill

by mowing), while

also building up as much organic matter in the soil as possible.

Meanwhile, I wanted to learn the best planting dates in order to grow

vegetables for as much of the year as possible and still find time to

slide in a cover crop planting.

Cover

crops were another innovation in 2010, doing double-duty as weed

suppressors and compost creators. My first goal was to find

varieties that like our clay soil and work well with no-till conditions

in zone 6 (i.e. they die over the winter or are easy to kill

by mowing), while

also building up as much organic matter in the soil as possible.

Meanwhile, I wanted to learn the best planting dates in order to grow

vegetables for as much of the year as possible and still find time to

slide in a cover crop planting.

Here's a rundown on each

species I tried, with the caveat that the December snow coat prevented

a winter kill in several species that I suspect will still die out

before spring planting time. I also can't tell how much organic

matter has been added to the soil yet --- I'll try to remember to post

again when I delve into the dirt in each bed and notice the differences

between crops, but for now I'm just making guesses based on how much

vegetation is on the surface.

Here's a rundown on each

species I tried, with the caveat that the December snow coat prevented

a winter kill in several species that I suspect will still die out

before spring planting time. I also can't tell how much organic

matter has been added to the soil yet --- I'll try to remember to post

again when I delve into the dirt in each bed and notice the differences

between crops, but for now I'm just making guesses based on how much

vegetation is on the surface.

- Oats are currently my very favorite cover crop. They had no problem with our heavy clay soil and thrived even in the most water-logged beds, creating more top growth than any other cover crop we tried. Forage oats that I bought in a 50 pound bag at the feed store grew much better than hull-less oats, and the oats also seemed to need a top-dressing of compost to achieve maximum growth (which is worth it to me, although some people might wonder about using compost to grow compost.) The best planting period for oats in our garden seems to extend from the beginning of August (or possibly earlier?) through mid September --- the earliest ones bloomed two months later and had to be cut down, which is a bit of extra work but not a significant deterrent, while the late September and October planted oats just didn't get big enough to make it worth our while. The jury is still out on whether oats will winter kill, but mowing them is easy and weakens the plants enough that they die in even a moderate cold snap.

Oilseed radishes

are currently my second favorite cover crop, perhaps to be promoted to

favorite once I dig into the dirt --- they produce most of their

biomass below ground, so I can only guess at how their organic matter

production will stack up compared to oats. The only downside of

oilseed radishes is seed cost --- you can't buy the seeds at the feed

store, so you're stuck paying shipping and a higher price through

online suppliers (and they're new and trendy, so they cost a

lot.) Otherwise, though, the radishes do just as well as oats at

growing fast, putting up with clay soil and waterlogged conditions, and

outcompeting weeds. They are currently about two-thirds

winter-killed too, so I'm pretty sure I won't need to do any mowing to

wipe the radish cover crop out in the spring. As for planting

date, I planted radishes each week in September, and the earliest ones

definitely did better than the later ones, so I suspect their optimal

planting date is around the same as for oats, perhaps leaning a hair

toward earlier planting.

Oilseed radishes

are currently my second favorite cover crop, perhaps to be promoted to

favorite once I dig into the dirt --- they produce most of their

biomass below ground, so I can only guess at how their organic matter

production will stack up compared to oats. The only downside of

oilseed radishes is seed cost --- you can't buy the seeds at the feed

store, so you're stuck paying shipping and a higher price through

online suppliers (and they're new and trendy, so they cost a

lot.) Otherwise, though, the radishes do just as well as oats at

growing fast, putting up with clay soil and waterlogged conditions, and

outcompeting weeds. They are currently about two-thirds

winter-killed too, so I'm pretty sure I won't need to do any mowing to

wipe the radish cover crop out in the spring. As for planting

date, I planted radishes each week in September, and the earliest ones

definitely did better than the later ones, so I suspect their optimal

planting date is around the same as for oats, perhaps leaning a hair

toward earlier planting.

Annual ryegrass got off to a much

slower start than oats and oilseed radishes, but it seems to have kept

growing later in the year as well. When I went out to check on it

after the snow melted, I was surprised to find such a dense growth on

the ryegrass beds, and it's possible ryegrass might do as well as my

oats, especially when a bed opens up for cover crops later in the

year. Beds planted on September 1 did the best, but those planted

at the end of September did better than oats planted on neighboring

beds on the same day. The real question will be whether annual

ryegrass will winter kill since we're on the edge of its hardiness zone

and the beds are still bright green. If so, I'd plant annual

ryegrass on any bed that opens up between mid September and early

October.

Annual ryegrass got off to a much

slower start than oats and oilseed radishes, but it seems to have kept

growing later in the year as well. When I went out to check on it

after the snow melted, I was surprised to find such a dense growth on

the ryegrass beds, and it's possible ryegrass might do as well as my

oats, especially when a bed opens up for cover crops later in the

year. Beds planted on September 1 did the best, but those planted

at the end of September did better than oats planted on neighboring

beds on the same day. The real question will be whether annual

ryegrass will winter kill since we're on the edge of its hardiness zone

and the beds are still bright green. If so, I'd plant annual

ryegrass on any bed that opens up between mid September and early

October.

- Buckwheat was a

disappointment. The plants hated waterlogged clay soil, and even

where buckwheat seemed to grow well, very little biomass was left

behind. Buckwheat's main advantages are that it will grow fast,

reaching maturity in just a bit over a month, and that the crop is very

easy to mow-kill. I could envision planting buckwheat in a bed

that was being reserved for a late spring planting, but I don't think

it's worth using up prime fall beds with buckwheat.

Barley

is still a big question mark. I planted it on a whim in late

October, and the plants didn't do much. Clearly, I'll have to try

again at a more realistic planting date.

Barley

is still a big question mark. I planted it on a whim in late

October, and the plants didn't do much. Clearly, I'll have to try

again at a more realistic planting date.

- Crimson Clover is also a

"who knows." I seeded clover in early October, and it came up and

produced its first set of true leaves before the cold weather hit, but

it's hard to tell anything else.

Looking beyond the

minutae, cover crops are a great addition to the garden, and I can't

imagine why it took me so long to come on board. (Well, I know

why --- I thought they were incompatible with no-till.) Cover

crops keep the soil from eroding and the food web alive in the fall

after the main garden is done, and it really

perks me up to look out at a sea of colors in November rather than at a

lot of dead stalks.

If I had to make only one recommendation to gardeners based on my 2010

vegetable garden experiments, it would be "Plant cover crops!"

This post is part of our 2010 experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

2010 was the year we figured out the power of having a large truck to

haul big loads and just how much of a time saver it can be.

Joey

was kind enough to make us an offer to transfer ownership and we were

happy to accept. Of course he retains shared custody for times when he

needs to move something large.

It's that time of year when

the ground temperature determines if the truck can move or just spin in

the mud. So far when it gets stuck the course of action is to wait till

it freezes, which is a lot easier than using a hand winch like we did

in the good old days with the Isuzu baby truck.

I

saved up a few special books as treats to take along on our recent

cruise, one of which was Holy

Shit: Managing Manure to Save Mankind by Gene Logsdon. I

have to admit that I was partly saving the book because it made me

laugh to envision reading a book called Holy Shit on a cruise, but I was

also really looking forward to learning more about one of my favorite

forms of biomass. I've thoroughly enjoyed several of Gene

Logsdon's other books, like Small-Scale

Grain Raising,

so I figured I was in for a treat.

I

saved up a few special books as treats to take along on our recent

cruise, one of which was Holy

Shit: Managing Manure to Save Mankind by Gene Logsdon. I

have to admit that I was partly saving the book because it made me

laugh to envision reading a book called Holy Shit on a cruise, but I was

also really looking forward to learning more about one of my favorite

forms of biomass. I've thoroughly enjoyed several of Gene

Logsdon's other books, like Small-Scale

Grain Raising,

so I figured I was in for a treat.

Unfortunately, Holy Shit let me down. I was

hoping for some data and hands-on information that would help me use

manure more effectively on our homestead, but the book was instead an

extended rant on how our society is broken because we throw away our

manure. I kept my pen poised on my notebook for hours, and

couldn't come up with a single tip to write down and pass on to you

folks. If you're interested in reading Gene Logsdon's latest

book, I recommend you check it out of your local library as light

reading rather than seeking any answers in its pages.

After

four years of hard-core gardening, the vegetable garden doesn't require

much experimentation any more. I've mostly figured out when to

plant our crops, which varieties grow well in our soil, and how to

fight the worst diseases and pests. I do keep trying out new

experimental varieties, but I've discussed this year's successes and

failures previously (for example: amaranth, urd beans, other

experimental beans,

and quinoa,

sesame, and poppies.)

In this post, I just want to sum up our dealings with some of the

thornier issues --- how to

keep tomatoes from getting blight, how to keep cucurbits from dying of

anything and everything, and some work with woody plants.

After

four years of hard-core gardening, the vegetable garden doesn't require

much experimentation any more. I've mostly figured out when to

plant our crops, which varieties grow well in our soil, and how to

fight the worst diseases and pests. I do keep trying out new

experimental varieties, but I've discussed this year's successes and

failures previously (for example: amaranth, urd beans, other

experimental beans,

and quinoa,

sesame, and poppies.)

In this post, I just want to sum up our dealings with some of the

thornier issues --- how to

keep tomatoes from getting blight, how to keep cucurbits from dying of

anything and everything, and some work with woody plants.

2009

was the year without a tomato,

when every tomato in the eastern U.S. seems to have been impacted by

blight. We adore tomatoes, so we tried a lot of techniques to

keep our plants blight-free in 2010, including pruning

tomatoes to keep their leaves away from the damp soil, ripping

out any plants that contract the fungus, planting

blight-resistant tomato varieties, scattering

tomatoes throughout the garden and planting some later in the year, and weeding out

volunteer potatoes and weedy nightshades that can harbor the blight.

The combination of factors all added up to a good tomato year, despite

blight spores wafting through the air, although I don't think that the

tomato islands and succession planting did much good. We put away

enough tomatoes for pizza and spaghetti sauce, soups, and general

cooking to last us through the winter, and the only thing I would have

done differently would be to start drying

tomatoes earlier in

the year so we could have more of those delicious treats!

2009

was the year without a tomato,

when every tomato in the eastern U.S. seems to have been impacted by

blight. We adore tomatoes, so we tried a lot of techniques to

keep our plants blight-free in 2010, including pruning

tomatoes to keep their leaves away from the damp soil, ripping

out any plants that contract the fungus, planting

blight-resistant tomato varieties, scattering

tomatoes throughout the garden and planting some later in the year, and weeding out

volunteer potatoes and weedy nightshades that can harbor the blight.

The combination of factors all added up to a good tomato year, despite

blight spores wafting through the air, although I don't think that the

tomato islands and succession planting did much good. We put away

enough tomatoes for pizza and spaghetti sauce, soups, and general

cooking to last us through the winter, and the only thing I would have

done differently would be to start drying

tomatoes earlier in

the year so we could have more of those delicious treats!

We

also mostly licked our cucurbit problems. In the past, we've lost

many of our squashes to vine borers and our cucumbers and melons to

wilts and blights, and we've tried lots of complicated methods to solve

these problems. In the end, it seems like the lowest tech answers

are the best when it comes to cucurbits. Among winter squashes,

we simply converted

over to an all-butternut garden, which deleted all of the

issues and also fed us the tastiest of the winter squashes. For

summer squashes, we settled on succession

planting, seeding a

new bed May 1, May 15, June 1, June 15, July 15, and July 30. As

soon as the earlier bed succumbed to vine borers, the next bed was

producing, and our freezer is chock full of squash slices. We

used nearly the same succession planting technique with cucumbers, with

the addition that we chose a more mildew-resistant variety (Diamont

Hybrid), and for the first time we were overrun with cucumbers for most

of the summer. We had a so-so watermelon year, but the problem

there was mislabelled seeds. In the end, the only cucurbit that

still eludes me is canteloupes --- since these plants need a long

growing season like winter squash, I can't just succession plant to

beat the blight. Maybe some research will turn up a more

resistant variety, or perhaps I'll follow my movie star neighbor's lead

and plant canteloupes atop black plastic for faster drying.

We

also mostly licked our cucurbit problems. In the past, we've lost

many of our squashes to vine borers and our cucumbers and melons to

wilts and blights, and we've tried lots of complicated methods to solve

these problems. In the end, it seems like the lowest tech answers

are the best when it comes to cucurbits. Among winter squashes,

we simply converted

over to an all-butternut garden, which deleted all of the

issues and also fed us the tastiest of the winter squashes. For

summer squashes, we settled on succession

planting, seeding a

new bed May 1, May 15, June 1, June 15, July 15, and July 30. As

soon as the earlier bed succumbed to vine borers, the next bed was

producing, and our freezer is chock full of squash slices. We

used nearly the same succession planting technique with cucumbers, with

the addition that we chose a more mildew-resistant variety (Diamont

Hybrid), and for the first time we were overrun with cucumbers for most

of the summer. We had a so-so watermelon year, but the problem

there was mislabelled seeds. In the end, the only cucurbit that

still eludes me is canteloupes --- since these plants need a long

growing season like winter squash, I can't just succession plant to

beat the blight. Maybe some research will turn up a more

resistant variety, or perhaps I'll follow my movie star neighbor's lead

and plant canteloupes atop black plastic for faster drying.

I've learned a lot about

propagating perennials this year, too, but was much less successful

with my first attempts. I easily got

hardy kiwis to root from softwood cuttings, but then transplanted them

straight into the unirrigated part of the garden when their roots were

too small, and the plants promptly kicked the bucket. Since the

original kiwi vines seem to have really taken off this year (their

second full summer in the ground), I figure I'll have a lot more

material to root next year and can try again. I also completely

failed at starting

various trees from seed since I didn't count on

their slow germination and lost track of exactly where I'd planted

them. This year, I'm starting

seeds that need stratification in pots, and also plan to put down a

kill mulch and start a little nursery area up by the water tank.

I've learned a lot about

propagating perennials this year, too, but was much less successful

with my first attempts. I easily got

hardy kiwis to root from softwood cuttings, but then transplanted them

straight into the unirrigated part of the garden when their roots were

too small, and the plants promptly kicked the bucket. Since the

original kiwi vines seem to have really taken off this year (their

second full summer in the ground), I figure I'll have a lot more

material to root next year and can try again. I also completely

failed at starting

various trees from seed since I didn't count on

their slow germination and lost track of exactly where I'd planted

them. This year, I'm starting

seeds that need stratification in pots, and also plan to put down a

kill mulch and start a little nursery area up by the water tank.

This post is part of our 2010 experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

This picture shows a medium

size pile of horse manure in front of the large mass of wood chips near

our parking area.

That load of horse dung

represents years of back and forth with the guy who scoops it out of

the neighbors barn. My timing was just right last week on New Years Eve

when I was driving home from the store with some beer and happened to

notice the guy pull in to the driveway of the barn full of organic gold

as Anna sometimes calls it.

I stopped....shared a couple

beers....casually mentioned how easy it might be for him to dump the

latest horse manure next to our wood chips instead of the previous

place. Talked about

chicken waterers and sweet potatos and headed on home.

In my opinion the moral of

this story is to never under estimate the motivation that a cold beer

can inspire.

Doesn't

that look like a useful pile of biomass?

Doesn't

that look like a useful pile of biomass?

Mark pointed out to me

last week that our miter saw channels the sawdust

(mostly) through a little tube in the back of the saw.

Presumably, the purpose is to enable you to hook the saw up to a bag or

vaccuum system to keep your house from turning into a mess when using

the miter saw indoors, but Mark has a plan to add a hose to the opening

and channel that sawdust into a five gallon bucket. Meanwhile,

I've just been scooping it up and adding it to various mulch piles.

Mark dreams of providing

so much biomass that I get sick and tired of it, a bit like parents who

make their kids smoke a whole pack of cigarettes if they catch them

easing into the bad habit at a young age. I'm afraid I'm already

too addicted, though, for his strategy to work.

I'll

end my run-down on 2010 experiments with the ones nearest and dearest

to my heart --- the forest garden. My forest garden trials are by

far the most experimental, so it's no surprise that most of them didn't

do all that well. You should also keep in mind that I planted my

primary forest garden in the worst part of the yard, where the topsoil

eroded away under the care of previous owners leaving behind solid clay

with an abnormally high groundwater. Quite possibly, these

techniques would have worked in more prime garden soil.

I'll

end my run-down on 2010 experiments with the ones nearest and dearest

to my heart --- the forest garden. My forest garden trials are by

far the most experimental, so it's no surprise that most of them didn't

do all that well. You should also keep in mind that I planted my

primary forest garden in the worst part of the yard, where the topsoil

eroded away under the care of previous owners leaving behind solid clay

with an abnormally high groundwater. Quite possibly, these

techniques would have worked in more prime garden soil.

I've

read in several books that comfrey makes a great living mulch beneath

fruit trees, sucking up nutrients from deep in the subsoil with its

taproots and then depositing the hard-to-find minerals right by the

tree roots. Unfortunately, my

experience with comfrey around fruit trees is entirely negative ---

the tree with comfrey around its base seems to be growing slower and

its summer leaves were yellowish, suggesting that the comfrey is

fighting the tree for nitrogen. While this experiment has no

control (I put the comfrey around my only nectarine and can only

compare it to the closely related peaches planted in another part of

the yard), I'd be leery of planting comfrey around any other fruit

trees, and am planning on putting down a kill mulch to try to eradicate

the comfrey from around my nectarine. It's possible that comfrey

makes a good living mulch around the drip-line of more established

fruit trees, but for now I'm sticking to planting my comfrey where it

won't fight with anyone, then cutting the leaves for mulch.

I've

read in several books that comfrey makes a great living mulch beneath

fruit trees, sucking up nutrients from deep in the subsoil with its

taproots and then depositing the hard-to-find minerals right by the

tree roots. Unfortunately, my

experience with comfrey around fruit trees is entirely negative ---

the tree with comfrey around its base seems to be growing slower and

its summer leaves were yellowish, suggesting that the comfrey is

fighting the tree for nitrogen. While this experiment has no

control (I put the comfrey around my only nectarine and can only

compare it to the closely related peaches planted in another part of

the yard), I'd be leery of planting comfrey around any other fruit

trees, and am planning on putting down a kill mulch to try to eradicate

the comfrey from around my nectarine. It's possible that comfrey

makes a good living mulch around the drip-line of more established

fruit trees, but for now I'm sticking to planting my comfrey where it

won't fight with anyone, then cutting the leaves for mulch.

Meanwhile,

I installed swales around several fruit trees

in an attempt to drain a bit of water away from their roots and keep

the forest garden from turning into a morass of mud in the

winter. In areas where the groundwater is extremely high, the

swales just made the muddy area larger --- ditches would have been a

better choice. On the other hand, in moderately problematic area,

the swales nearly did the job, just leaking a bit of water to the

downhill side. When I find enough organic matter, I plan to fill

the good swales up with mulch and also to add an extensive kill mulch

around each fruit tree in this trouble area so that the tree roots can

benefit from the concentrated water in the dry period of summer.

Meanwhile,

I installed swales around several fruit trees

in an attempt to drain a bit of water away from their roots and keep

the forest garden from turning into a morass of mud in the

winter. In areas where the groundwater is extremely high, the

swales just made the muddy area larger --- ditches would have been a

better choice. On the other hand, in moderately problematic area,

the swales nearly did the job, just leaking a bit of water to the

downhill side. When I find enough organic matter, I plan to fill

the good swales up with mulch and also to add an extensive kill mulch

around each fruit tree in this trouble area so that the tree roots can

benefit from the concentrated water in the dry period of summer.

My hugelkultur mounds

--- rotting wood topped with soil --- did what I wanted only too

well. I hoped they would keep plants out of the groundwater in

the trouble spots, but the small amount of soil and large amount of

not-yet-rotted wood in the mounds meant that during year one, they were

too dry for anything except rosemary. Also, Lucy loved

digging my mounds up in search of small mammals. On the other hand, I

think that hugelkultur has a lot of potential for my forest garden if I

can put them in spots where nothing needs to grow for a year or two

until the wood really breaks down. This year, I'm creating

hugelkultur extensions to each tree mound to give my fruit trees more

dry ground to spread out, and this time I'm putting a layer of

cardboard below each mound so tenacious weeds won't grow up through.

My hugelkultur mounds

--- rotting wood topped with soil --- did what I wanted only too

well. I hoped they would keep plants out of the groundwater in

the trouble spots, but the small amount of soil and large amount of

not-yet-rotted wood in the mounds meant that during year one, they were

too dry for anything except rosemary. Also, Lucy loved

digging my mounds up in search of small mammals. On the other hand, I

think that hugelkultur has a lot of potential for my forest garden if I

can put them in spots where nothing needs to grow for a year or two

until the wood really breaks down. This year, I'm creating

hugelkultur extensions to each tree mound to give my fruit trees more

dry ground to spread out, and this time I'm putting a layer of

cardboard below each mound so tenacious weeds won't grow up through.

As

you can tell from the photos, my favorite part of the forest garden is

that I get to play with it in the winter when a dormant vegetable

garden combined with the garden itch would otherwise itch drive me

nutty. The forest garden pretty much takes care of itself for the

rest of the year, so it's hard to complain about some growing

pains. And, lest you still become disheartened from this dismal

list of problems, I should also tell you that my forest

garden island (in

the portion of the garden with good soil) is huge and provided masses

of fruits for us --- clearly, permaculture concepts have a lot of merit

even if they have to be tweaked a bit to work in the most problematic

parts of the yard.

As

you can tell from the photos, my favorite part of the forest garden is

that I get to play with it in the winter when a dormant vegetable

garden combined with the garden itch would otherwise itch drive me

nutty. The forest garden pretty much takes care of itself for the

rest of the year, so it's hard to complain about some growing

pains. And, lest you still become disheartened from this dismal

list of problems, I should also tell you that my forest

garden island (in

the portion of the garden with good soil) is huge and provided masses

of fruits for us --- clearly, permaculture concepts have a lot of merit

even if they have to be tweaked a bit to work in the most problematic

parts of the yard.

This post is part of our 2010 experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

The

guy at the wood stove store mentioned how they have a problem with

these high quality pallets stacking up behind their store.

The

guy at the wood stove store mentioned how they have a problem with

these high quality pallets stacking up behind their store.

I'm thinking of planning the

next big city trip with a visit to this alley. He just wants to get rid

of them and says the local pallet guys aren't interested because of the

irregular shapes. They seem to be of a higher grade than normal pallets

which should make good firewood if no other uses come to mind.

I've been itching for a soil

thermometer, but haven't wanted to pay for shipping and couldn't find

one locally. When we were in Wal-Mart the other day, I stumbled

across a meat thermometer in the cooking section that I suspected would

do the job. As far as I can tell, the only difference between a

typical meat thermometer and a soil thermometer is that the latter

tends to measure lower temperatures, and the Mainstays Quick-Response

Thermometer goes all the way down to 0 degrees Fahrenheit so that you

can test meat temperatures in the freezer as well as on the grill ---

perfect!

I've been itching for a soil

thermometer, but haven't wanted to pay for shipping and couldn't find

one locally. When we were in Wal-Mart the other day, I stumbled

across a meat thermometer in the cooking section that I suspected would

do the job. As far as I can tell, the only difference between a

typical meat thermometer and a soil thermometer is that the latter

tends to measure lower temperatures, and the Mainstays Quick-Response

Thermometer goes all the way down to 0 degrees Fahrenheit so that you

can test meat temperatures in the freezer as well as on the grill ---

perfect!

I gave my new soil

thermometer a test run in the chicken coop's deep bedding yesterday and was highly

impressed to see that composting action raises the temperature from the

exterior soil temperature (27 degrees Fahrenheit) to a toasty 58

degrees! Just think how useful this thermometer will be to help

me figure out when the soil is warm enough to plant peas (35 to 40

degrees.) Usually, I just put the seeds in the ground two or

three times throughout the late winter in hopes that I'll hit on the

right soil temperature by chance, and I suspect adding a little science

to the mix will save me the $7.97 cost of the thermometer in lowered

seed costs during the first year.

I gave my new soil

thermometer a test run in the chicken coop's deep bedding yesterday and was highly

impressed to see that composting action raises the temperature from the

exterior soil temperature (27 degrees Fahrenheit) to a toasty 58

degrees! Just think how useful this thermometer will be to help

me figure out when the soil is warm enough to plant peas (35 to 40

degrees.) Usually, I just put the seeds in the ground two or

three times throughout the late winter in hopes that I'll hit on the

right soil temperature by chance, and I suspect adding a little science

to the mix will save me the $7.97 cost of the thermometer in lowered

seed costs during the first year.

Now, if I can just

remember not to stick my chicken-poop-covered thermometer into a juicy

steak....

Days

when the snow fills the air are perfect for planning next summer's

garden and ordering seeds. The first step is to go through all of

my old seeds to see which ones will last another year and which ones

need to be replaced. I've posted previously about how long

seeds last,

but you have to take that chart with a grain of salt --- we live in a

very humid climate and I haven't gotten around to making a good seed

storage box, so some of our seeds have less longevity than they

should. For example, some turnip seeds that I thought had a year

or two left in them completely failed to germinate in 2010, so those

bit the dust and will be replaced.

Days

when the snow fills the air are perfect for planning next summer's

garden and ordering seeds. The first step is to go through all of

my old seeds to see which ones will last another year and which ones

need to be replaced. I've posted previously about how long

seeds last,

but you have to take that chart with a grain of salt --- we live in a

very humid climate and I haven't gotten around to making a good seed

storage box, so some of our seeds have less longevity than they

should. For example, some turnip seeds that I thought had a year

or two left in them completely failed to germinate in 2010, so those

bit the dust and will be replaced.

Meanwhile, I had five

species that I just wasn't sure of. One was

parsley that I harvested this year in the garden, but am not sure I

matured well enough on the plant. Another is bean seeds saved

from 2009 (or was it 2008?). Last year's corn and peanut

seeds should still be good, but both can have low germination rates

after the first year, so I wanted to try them out. Finally, I

have extra onion seeds from last year, but they didn't germinate well

in the spring garden --- did I just plant them when the soil was too

cold, or were the seeds a dud to begin with?

I

placed five seeds of each questionable variety between two moistened

cloth

napkins in a plastic container for a germination test. Those of

you with conventional kitchens may choose to use paper towels, but

disposables are verboten in our household. Since all of these

seeds

prefer relatively warm temperatures for germination, I've situated the

container on the back of the electric stove where heat from the wood

stove keeps temperatures around 70 degrees during the day. Night

temperatures will fall much lower, but I'll just add a few days onto my

germination test to take that into consideration. In conventional

kitchens, finding a warm spot is often easier --- just put your

germination chamber on top of the fridge or hot water tank.

I

placed five seeds of each questionable variety between two moistened

cloth

napkins in a plastic container for a germination test. Those of

you with conventional kitchens may choose to use paper towels, but

disposables are verboten in our household. Since all of these

seeds

prefer relatively warm temperatures for germination, I've situated the

container on the back of the electric stove where heat from the wood

stove keeps temperatures around 70 degrees during the day. Night

temperatures will fall much lower, but I'll just add a few days onto my

germination test to take that into consideration. In conventional

kitchens, finding a warm spot is often easier --- just put your

germination chamber on top of the fridge or hot water tank.

Now I just need to wait

and see what happens. See

this site for optimal germination temperature and time to germination

for many common vegetables. After two and a half

weeks have passed, I'll conclude the experiment and order any of the

seeds that didn't germinate well, or choose to just double or triple my

seeding rate for the spring.

This is the 2nd time I've

managed to get the truck stuck in the mud this winter season.

Each time has been an

opportunity to help gauge the limitations of its traction.

I think getting stuck pushes

my "loss of power" buttons in the same way not knowing where

I'm at does.

The lesson I've been trying

to learn lately is to not get so bent out of shape when these dips in

power happen. My first instinct is to react in a way that solves the

problem in the easiest and quickest way possible, but my latest

findings seem to indicate that there is often an advantage to stepping

back and looking at a problem from a few different perspectives.

The week before Mark's

birthday, I try to take a bit of time every day to appreciate the

specialness of my sweet husband. I don't buy him flowers or

candy, but I do try to cook his favorite foods (especially things like

hamburgers with white buns that don't make the diet-police cut during

the rest of the year, or more time-consuming treats like potstickers

that don't spring to mind when I'm pulling together a quick

supper.) This year I took over the dishes for the week --- I

suspect Mark would rather have those couple of extra hours of freedom

rather than a toy I picked up on a whim at the store. It's not

much, but I hope he feels appreciated. Happy birthday, honey!

Permaculture books trip over

themselves to toss out the names of intriguing perennial vegetables,

but the books are short on specifics of where and how these vegetables

can be grown. When I heard that Eric Toensmeier (co-author of Edible Forest Gardens) had written a book called Perennial

Vegetables, I

knew I'd fond the holy grail, but I put off reading Toensmeier's book

for one simple reason --- I knew that I'd want to buy every vegetable

listed. So, be forewarned --- don't pick up this book unless

you've got $100 or more burning a hole in your pocket.

Permaculture books trip over

themselves to toss out the names of intriguing perennial vegetables,

but the books are short on specifics of where and how these vegetables

can be grown. When I heard that Eric Toensmeier (co-author of Edible Forest Gardens) had written a book called Perennial

Vegetables, I

knew I'd fond the holy grail, but I put off reading Toensmeier's book

for one simple reason --- I knew that I'd want to buy every vegetable

listed. So, be forewarned --- don't pick up this book unless

you've got $100 or more burning a hole in your pocket.

Perennial

Vegetable

provides cultivation information for over 100 plants that are grown for

edible leaves, shoots, tubers, and more. In this lunchtime series, I've picked out the crops that I find the most

intriguing, but I highly recommend that you read the book yourself,

especially if you live further south than zone 6 --- over half of the

species like warmer temperatures, so I skipped over them. My list

is also low on tubers because we don't eat that may of them and I'm

very happy with our potatoes and sweet potatoes. Tuber-lovers

should look up Perennial

Vegetables to

read about additional crops like lotuses, skirret, Jerusalem artichokes, and Chinese yams.

Finally, if you want to

get a head-start on checking out which plants might suit your climate,

you can go directly to Eric Toensmeier's website and find plant lists for

various parts of the U.S., a list of other books to read, and sources

for perennial vegetable seeds and starts. Or drop a comment here

to let me know which perennial vegetables you've tried in your own

garden.

| This post is part of our Perennial Vegetables lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

This experiment is still in

the planning stages...but one of these small metal tubs placed on

top of the Jotul

F 602 wood stove does a good job at reaching temperatures suitable

for baking.

The goal is to see if it's

possible or practical to bake muffins.

Of course the temperature

will depend on the size of the fire, but this first test proves that

reaching the main baking temperature of 350 degrees is indeed workable.

The idea is to use a couple of fire bricks to support the muffin pan

which might be enough to prevent the pan from getting too hot and

burning the product.

When I mentioned our goal

of making a small oven on top of the wood stove,

Roland pointed out that it's essential to do some basic tests first and

make sure the stove top temperature is within baking range.

Purchasing an oven thermometer in order to make those tests was the

real reason we

were in the kitchen section of Wal-mart to pick up my meat

thermometer turned soil thermometer.

When I mentioned our goal

of making a small oven on top of the wood stove,

Roland pointed out that it's essential to do some basic tests first and

make sure the stove top temperature is within baking range.

Purchasing an oven thermometer in order to make those tests was the

real reason we

were in the kitchen section of Wal-mart to pick up my meat

thermometer turned soil thermometer.

I compared three

different permutations to get an idea of stove top

temperatures while the wood stove was running at medium to high

heat. First, I just put the oven thermometer on a fire brick on

the hot-plate section of the wood stove top and got a reading of 210

degrees Fahrenheit --- not that hot. But when I upending the

galvanized

basin Mark had

bought for the purpose over top of the whole wood stove, the addition

raised the

internal temperature to 525 degrees. (You don't see the fire

brick in the photo because I actually did a test without it the

first time around, but figured the off-the-chart reading just couldn't

be

right.)

The fire brick didn't quite

fit into the Dutch oven, so I first tested with the thermometer set on

the bottom of the cast iron pot and got a reading of 475 degrees.

Figuring a lot of heat was getting conducted from the metal of the pan

to the metal of the thermometer, but unable to add in a fire brick

because it was too large, I set a pot holder on the bottom of the oven

with the thermometer on top. Ten minutes later, a foul stench

filled the trailer --- the pot holder had spontaneously

combusted. So, unfortunately, I can't tell you whether Mark's

idea of cutting down the sides of a 6-pack muffin tin so that it sits

on a fire brick inside the Dutch oven will give me temperatures

sufficient to bake his favorite sweet treat. Clearly, more

experiments are required.

The fire brick didn't quite

fit into the Dutch oven, so I first tested with the thermometer set on

the bottom of the cast iron pot and got a reading of 475 degrees.

Figuring a lot of heat was getting conducted from the metal of the pan

to the metal of the thermometer, but unable to add in a fire brick

because it was too large, I set a pot holder on the bottom of the oven

with the thermometer on top. Ten minutes later, a foul stench

filled the trailer --- the pot holder had spontaneously

combusted. So, unfortunately, I can't tell you whether Mark's

idea of cutting down the sides of a 6-pack muffin tin so that it sits

on a fire brick inside the Dutch oven will give me temperatures

sufficient to bake his favorite sweet treat. Clearly, more

experiments are required.

Before

I delve right into the most intriguing

plants from Eric Toensmeier's Perennial Vegetables, it's

worth taking a minute to see if perennial vegetables are right for

you. The advantages are intriguing. Since you don't have to

plant them every year, perennial vegetables are low maintenance and

work very well with no-till systems, building soil quality with their

decaying leaves. Some are shade tolerant, which is seldom true

with annual vegetables, so you can slide these perennials into out of

the way spots in your garden. Even more intriguing, perennial

vegetables

extend the harvest season, often providing food when your annual

vegetable garden is at its worst. I was won over this March when

I wandered out into the yard and picked

some mulch-blanched dandelion greens long before any of our

annual

greens were ready to eat --- who wouldn't want delicious food that they

hadn't worked for when no other fresh food is available?

Before

I delve right into the most intriguing

plants from Eric Toensmeier's Perennial Vegetables, it's

worth taking a minute to see if perennial vegetables are right for

you. The advantages are intriguing. Since you don't have to

plant them every year, perennial vegetables are low maintenance and

work very well with no-till systems, building soil quality with their

decaying leaves. Some are shade tolerant, which is seldom true

with annual vegetables, so you can slide these perennials into out of

the way spots in your garden. Even more intriguing, perennial

vegetables

extend the harvest season, often providing food when your annual

vegetable garden is at its worst. I was won over this March when

I wandered out into the yard and picked

some mulch-blanched dandelion greens long before any of our

annual

greens were ready to eat --- who wouldn't want delicious food that they

hadn't worked for when no other fresh food is available?

As a certified picky eater,

the answer could

be "me." Toensmeier is very realistic about the potential of

perennial vegetables, and goes so far as to explain that many perennial

vegetables are too strong-flavored to be a mainstay of the diet.

Perennial greens are usually at their best just when I picked my March

dandelions (which were scrumptious, by the way), but later in the year

after the perennials bloom, you'd be much better off eating swiss chard

out of your annual garden. Another disadvantage is that many

perennial vegetables take years to establish, just like asparagus or

fruit trees, and since you can't rotate perennials through your garden,

viral diseases can build up and wipe out your crop. Other

perennials are altogether too tenacious, turning into weeds in your

garden, and non-vegetable weeds can be yet another problem among your

perennials if you're not adept at creating weed-free no-till beds.

As a certified picky eater,

the answer could

be "me." Toensmeier is very realistic about the potential of

perennial vegetables, and goes so far as to explain that many perennial

vegetables are too strong-flavored to be a mainstay of the diet.

Perennial greens are usually at their best just when I picked my March

dandelions (which were scrumptious, by the way), but later in the year

after the perennials bloom, you'd be much better off eating swiss chard

out of your annual garden. Another disadvantage is that many

perennial vegetables take years to establish, just like asparagus or

fruit trees, and since you can't rotate perennials through your garden,