Eastern agricultural complex

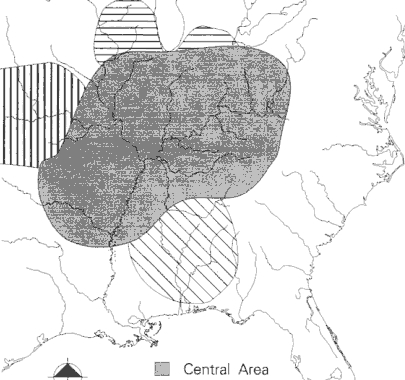

Most

laypeople believe that eastern native Americans didn't start farming

until corn, beans, and squash made their way north from Mexico,

becoming common crops around 1000 AD. But well before then,

Native Americans in the area shaded on this map had domesticated a

whole suite of other crops. These plants, known as the Eastern

Agricultural Complex, may have made up as much as 67% of the diet of

the Native Americans 2500 years ago, with the history of the plants'

cultivation extending perhaps as far back as 2050 BC.

Most

laypeople believe that eastern native Americans didn't start farming

until corn, beans, and squash made their way north from Mexico,

becoming common crops around 1000 AD. But well before then,

Native Americans in the area shaded on this map had domesticated a

whole suite of other crops. These plants, known as the Eastern

Agricultural Complex, may have made up as much as 67% of the diet of

the Native Americans 2500 years ago, with the history of the plants'

cultivation extending perhaps as far back as 2050 BC.

Oily

seeds were an important part of the Eastern Agricultural

Complex. We're still familiar with one of these eastern North

American natives --- sunflowers. Another oil-seed crop is

familiar for a different reason --- the original squashes cultivated

in eastern North America had an inedible flesh and were instead grown

for their tasty seeds. Finally, sumpweed (also known as

marsh-elder) was an important crop which produced nutritional seeds

made up of 32% protein and 45% oil, but which has largely disappeared

from our knowledge-base. Gayle

Fritz's Laboratory Guide to

Archaeological Plant Remains from Eastern North America notes that "Harvesting

experiments using wild stands show that sumpweed holds considerable

economic potential."

Oily

seeds were an important part of the Eastern Agricultural

Complex. We're still familiar with one of these eastern North

American natives --- sunflowers. Another oil-seed crop is

familiar for a different reason --- the original squashes cultivated

in eastern North America had an inedible flesh and were instead grown

for their tasty seeds. Finally, sumpweed (also known as

marsh-elder) was an important crop which produced nutritional seeds

made up of 32% protein and 45% oil, but which has largely disappeared

from our knowledge-base. Gayle

Fritz's Laboratory Guide to

Archaeological Plant Remains from Eastern North America notes that "Harvesting

experiments using wild stands show that sumpweed holds considerable

economic potential."

Small "grains" (meaning

plants with starchy seeds in this context) were

also important, and are mostly familiar to us now as garden

weeds. Look for lamb's quarter, maygrass, erect knotweed, and

little barley in your garden and think of their long history.

In the case of most of

the species in the Eastern Agricultural Complex,

Native Americans selected for plants that were easier to harvest or

better to eat, so we can distinguish the wild ancestors from the

domesticated versions in the archaeological  record.

As a result,

you shouldn't assume that the lamb's quarter you pull out of your

garden every year is the same as the one the Native Americans

grew. First of all, the most common lamb's quarter weed is in a

different species (Chenopodium

album instead of

Chenopodium

berlandieri).

Even if you tracked down a wild Chenopodium

berlandieri,

it probably wouldn't look much like the domesticated version since the

Native Americans bred their lamb's quarter to produce all of its

flowers at the same time and to concentrate the enlarged seeds in the

top inflorescence for easy harvest. In fact, like most of our

current garden vegetables, the varieties in the Eastern Agricultural

Complex had changed so much from the wild type that they depended on

humans to propagate

them and many couldn't reproduce or compete naturally in the wild.

record.

As a result,

you shouldn't assume that the lamb's quarter you pull out of your

garden every year is the same as the one the Native Americans

grew. First of all, the most common lamb's quarter weed is in a

different species (Chenopodium

album instead of

Chenopodium

berlandieri).

Even if you tracked down a wild Chenopodium

berlandieri,

it probably wouldn't look much like the domesticated version since the

Native Americans bred their lamb's quarter to produce all of its

flowers at the same time and to concentrate the enlarged seeds in the

top inflorescence for easy harvest. In fact, like most of our

current garden vegetables, the varieties in the Eastern Agricultural

Complex had changed so much from the wild type that they depended on

humans to propagate

them and many couldn't reproduce or compete naturally in the wild.

Are you interested in trying

to grow some of North America's most ancient

crops in your own garden. Too bad! Just as modern farmers

are ignoring the hundreds of varieties of heirloom vegetables

well-suited to their climate in favor of a few industrial varieties,

Native American farmers quickly ditched most components of the Eastern

Agricultural Complex when corn came on the scene. By the time of

European contact, all domesticated varieties except sunflowers and

squash were extinct.

Are you interested in trying

to grow some of North America's most ancient

crops in your own garden. Too bad! Just as modern farmers

are ignoring the hundreds of varieties of heirloom vegetables

well-suited to their climate in favor of a few industrial varieties,

Native American farmers quickly ditched most components of the Eastern

Agricultural Complex when corn came on the scene. By the time of

European contact, all domesticated varieties except sunflowers and

squash were extinct.

| This post is part of our Native American Paleoethnobotany lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

- Remove comment

- Remove comment