Hugelkultur

Davia

asked me if I'd ever heard of Hugelkultur. I thought the

answer was no, until I googled the term and discovered that hugelkultur

is very

similar to the mounds

I built last fall using dirt tossed over decomposing branches. Putting a name to the

method really expedited my research and turned up a lot more

information than I thought was out there. Thanks, Davia!

Davia

asked me if I'd ever heard of Hugelkultur. I thought the

answer was no, until I googled the term and discovered that hugelkultur

is very

similar to the mounds

I built last fall using dirt tossed over decomposing branches. Putting a name to the

method really expedited my research and turned up a lot more

information than I thought was out there. Thanks, Davia!

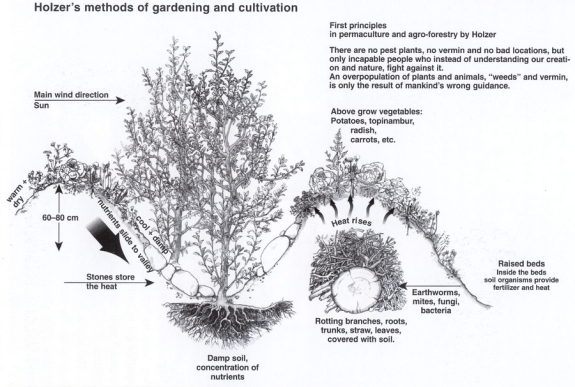

The idea is pretty

simple --- adding wood to a raised bed acts as a sponge, evening out

soil moisture so that the ground doesn't become waterlogged and also

doesn't dry up. As the wood rots, it turns into wonderful organic

matter a lot like the stump

dirt I rave about.

However, I think I made

a few mistakes with my hugelkultur beds. If you research the

technique, you'll discover that the correct way to make the beds is to

bury the woody material at least a foot or two under the earth. I

just built up piles of partly rotten branches and shoveled dirt in the

gaps, a method that worked okay for the hazels and wildflower mixes I

grew there, but that wouldn't have worked for vegetables. I'm

sure the branches are locking up nitrogen out of the soil as I type,

but everything I put in the beds is extremely resilient and seems to be

surviving.

The real problem is that

my beds are too dry. The wood hasn't rotted down enough yet to

act as a sponge, and the loosely shoveled clay has a lot of air pockets

that let water drain right through. Granted, I located the mounds

in an area where the groundwater is so high nothing will grow there, so

this "problem" isn't so bad --- it made a nice spot to put in rosemary

without ending up with root rot the way my rosemary plants usually do.

Problem number two is also

related to my haphazard construction. I left bits of branches

sticking out around the edges, which made Mark very leery of mowing up

to the sides of the mounds. Add to that the fact that my mulch

mostly blew away over the winter and I forgot to refresh it or weed the

mounds, and the result is a weed thicket. Surprisingly, the

thickly seeded wildflowers seem to be holding their ground against the

weeds, and the honeybees consider this area their second home, so all

is not lost.

Problem number two is also

related to my haphazard construction. I left bits of branches

sticking out around the edges, which made Mark very leery of mowing up

to the sides of the mounds. Add to that the fact that my mulch

mostly blew away over the winter and I forgot to refresh it or weed the

mounds, and the result is a weed thicket. Surprisingly, the

thickly seeded wildflowers seem to be holding their ground against the

weeds, and the honeybees consider this area their second home, so all

is not lost.

Now that I know more

about the technique, though, I want to try hugelkultur again as another

winter project. This time, I'll bury the wood deeper and plant a

cover crop to add fertility for the first year or so before planting

anything important. I'll be curious to see how quickly the

rotting wood starts benefiting my plants.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Hügelkultur is not a common German word.

Such a bed is properly named (and known as) a "Hügelbeet", which means "raised bed without a border". It is related to the Hochbeet; "raised bed with border". For those who don't read German, the second link has pictures.

According to the first link, you should put a fine steel mesh under your hill to protect it from voles and other arvicolinae.

Mrs. Fuzzy --- well rotted wood is golden (depending on how well rotted, of course)!

Roland --- I'm so glad you know German! I don't think the people who use the term were going for just "raised bed", though. Could the "kultur" part refer to the wood in some way?

The German word "kultur" means more or less the same as the English "culture" and the Dutch "cultuur". It can have different meanings depending on the context. In the context of a Hügelbeet it just means "a way of growing things on a hill". The word "agriculture" comes from the same Latin root; "agri cultura"; "working the field".

Nothing particular to do with wood, AFAIK. The German and Dutch words for wood are "Holz" resp. "hout", should you ever come across them. German and Dutch are related languages. They're often confused by native English speakers. There's this ethnic group in the US called "Pennsylvania Dutch" who are actually mostly of German descent.

The German and Dutch words for wood are "Holz" resp. "hout", should you ever come across them. German and Dutch are related languages. They're often confused by native English speakers. There's this ethnic group in the US called "Pennsylvania Dutch" who are actually mostly of German descent.

I don't think there are any constraints on soil type, but there are soils that would benefit from Hugelkultur more than others. The type I'm practicing is specialized to my waterlogged soil --- I'm not burying the wood in the ground, but instead putting down a kill mulch, adding the logs, and then topping it off with soil, mulch, and compost. If you had sandy soil with the opposite problem --- too much water loss --- I'd go back to the original method and bury the logs so that you hold onto more water.

The only real problem I've run into is small mammals moving into the rotting wood, which tempts my dog to dig them out and ruin the whole bed. Some folks put down a layer of hardware cloth under the wood in an attempt to keep the critters out. Of course, if you don't have a rodent-obsessed dog, that might not matter much.