archives for 12/2010

Darren pointed me toward worm

towers, which are a

way of integrating small-scale worm bins into your garden. As Milkwood explains, "Essentially a

worm tower is an in-garden worm farm that allows the

worms and their nutrients to interact directly with the surrounding

garden bed."

Darren pointed me toward worm

towers, which are a

way of integrating small-scale worm bins into your garden. As Milkwood explains, "Essentially a

worm tower is an in-garden worm farm that allows the

worms and their nutrients to interact directly with the surrounding

garden bed."

Simply take a two foot

long, 6" diameter PVC pipe, drill a bunch of holes around it for

aeration, bury it a foot deep in the soil of your garden, and fill it

with worms and bedding. Top the worm tower with a cap (like an

upturned flower pot) to protect the worms from the sun and then toss in

your food scraps and extra bedding just as you could in a normal worm

bin.

The innovative part is

that the plant roots and microorganisms in the surrounding soil can

also interact with the worm bin, sucking up worm tea and eating

castings as they appear. The worms can migrate down into the

below-ground portion of the worm tower when cold weather strikes, which

makes  this small-scale worm bin

much more able to deal with outdoor winter temperatures than the

typical household-size worm bin.

this small-scale worm bin

much more able to deal with outdoor winter temperatures than the

typical household-size worm bin.

I'm enthralled by the

idea and am suddenly envisioning a worm tower in each of our garden

beds, fed each week with cafeteria scraps and paper waste from the

local school. I guess the sticking point would be Lucy --- would

she dig up the worm tower to get to those rotting hamburgers?

Although

various waste products (like sawdust and wood chips) can be used as

bedding in the worm bin, Binet Payne found that shredded paper was the

most effective. I've just about talked myself into buying a

shredder to turn junk mail into worm bedding since that's one of the

few waste products we don't fully utilize on our farm, and since I've

had bad luck keeping worms going in the bedding materials I've used in

the past (leaves, unshredded paper, etc.) The trick is that worm

bedding should be high in carbon to counteract the high nitrogen food

wastes, should hold water well to keep the worms moist, and should stay

fluffy to allow plenty of air to circulate through the bin.

Although

various waste products (like sawdust and wood chips) can be used as

bedding in the worm bin, Binet Payne found that shredded paper was the

most effective. I've just about talked myself into buying a

shredder to turn junk mail into worm bedding since that's one of the

few waste products we don't fully utilize on our farm, and since I've

had bad luck keeping worms going in the bedding materials I've used in

the past (leaves, unshredded paper, etc.) The trick is that worm

bedding should be high in carbon to counteract the high nitrogen food

wastes, should hold water well to keep the worms moist, and should stay

fluffy to allow plenty of air to circulate through the bin.

When preparing your worm

bin the first time (or adding bedding later to

cover up food), soak your shredded paper with three times its weight in

water. The perfect bedding is damp but not soggy, so you can't

squeeze any water out by hand. If the bedding is too wet, just

let it drain in the bin for a while before adding your worms. As

the bedding drains, sprinkle a shovelful of dirt over the damp paper to

provide grit for your worms and to stock bacteria to expedite the

decomposition process. Then toss in a bit of food waste and

manure worms (Eisenia fetida), cover them up, and let

your worms get to work.

You

need to provide two pounds of worms for every daily pound of food

waste you'll be adding to the bin, which should also equal two pounds

of worms for every cubic foot of bin space. So, your 2 cubic foot

kitchen sink worm bin will need to start with 4 pounds of worms, and

your 8 foot by 4 foot by 1 foot bin will need 64 pounds of worms.

These

aren't the same worms you can dig up in your backyard, and buying

manure worms can be expensive, so you might need to stock your bin

with fewer worms than is recommended. In that case, add less food

waste to the bin at first, slowly putting in more as the worm

population grows. Binet Payne notes that 8 pounds of worms will

fully stock a 32 square foot bin within three months.

You

need to provide two pounds of worms for every daily pound of food

waste you'll be adding to the bin, which should also equal two pounds

of worms for every cubic foot of bin space. So, your 2 cubic foot

kitchen sink worm bin will need to start with 4 pounds of worms, and

your 8 foot by 4 foot by 1 foot bin will need 64 pounds of worms.

These

aren't the same worms you can dig up in your backyard, and buying

manure worms can be expensive, so you might need to stock your bin

with fewer worms than is recommended. In that case, add less food

waste to the bin at first, slowly putting in more as the worm

population grows. Binet Payne notes that 8 pounds of worms will

fully stock a 32 square foot bin within three months.

| This post is part of our Worm Cafe lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We spent some time today re-organizing the roost and nest box

placements in the chicken coop.

A fourth roosting location is

in the corner you don't see in the picture, which might be high enough

for our

rooster to finally feel like he's captain of the coop.

I'll check in on them a bit

after their bedtime tonight to see who ended up roosting on the top spot.

I've

been doing a lot of thinking about self-sufficiency lately. When

I was in my early twenties and dreaming of (and saving for) a

homestead, my goal was complete self-sufficiency. I imagined

parking at the corner of my wooded property and walking back to a tent,

where I lived until I'd cut down enough trees to make my home. I

had absolutely no contact with the outside world in this dream, and

needed none.

I've

been doing a lot of thinking about self-sufficiency lately. When

I was in my early twenties and dreaming of (and saving for) a

homestead, my goal was complete self-sufficiency. I imagined

parking at the corner of my wooded property and walking back to a tent,

where I lived until I'd cut down enough trees to make my home. I

had absolutely no contact with the outside world in this dream, and

needed none.

Age (and Mark's

mitigating influence) have slowly redefined my vision of

self-sufficiency to include the local community and beyond.

Rather than living without electricity for a couple of decades until we

saved enough for an off-grid power setup, we went ahead and plugged

into the cheap, mainstream grid, and reaped the benefits by making a living online. We take advantage of

the copious waste in American society, living

in a forty year old trailer that was being thrown away and trading

fresh eggs for horse manure. Nowadays, my vision

of self-sufficiency involves tricking talking enough like-minded

--- but subtly different --- neighbors into settling nearby so that we

could trade peaches for fresh milk and homegrown honey for half of a

pig rather than having to raise every sort of livestock ourselves.

That said, I have to

admit that I love days when we're flooded in and it becomes clear how

self-sufficient our homestead already is. Even without high creek

waters, we generally only go into town two days a week to mail our chicken waterers, hitting the grocery store

once every week or two for the scant provisions we don't grow

ourselves, and visiting the big city perhaps once or twice a month for

other supplies. Who cares if it floods Tuesday night when you're

not due to go into town until Friday anyway?

Binet Payne's method of

worm bin management is quite complex, but it can be summed up as

follows:

Only add

as much food as your bin can handle. The first step is to

audit your food waste over the course of a month and then build an

appropriately sized bin that you stock with the right number of

worms. Then weigh your food waste each day as you put it in the

bins to make sure the amount of food is close to the daily

average. If you get a sudden glut of food waste, use the extra in

a traditional compost pile or feed it to your chickens rather than

overwhelming the worm bin (and promoting fruit flies.)

Only add

as much food as your bin can handle. The first step is to

audit your food waste over the course of a month and then build an

appropriately sized bin that you stock with the right number of

worms. Then weigh your food waste each day as you put it in the

bins to make sure the amount of food is close to the daily

average. If you get a sudden glut of food waste, use the extra in

a traditional compost pile or feed it to your chickens rather than

overwhelming the worm bin (and promoting fruit flies.)- Keep food under cover. Every day when Binet's students add new food to her bins, they dig a trench across the width of the bin, put in the food, break up any large pieces of food with a shovel, then completely cover the food with bedding.

- Turn bins at least once a week

to double the compost speed. If you use the complicated

filling method I'll outline below, you'll need to turn each section

separately so that you don't mix old and new food waste together.

- Give your worms six weeks for the first round of composting. Binet Payne splits each of her four bins into eight sections and fills alternate sections every day, so she has completely filled the 32 sections in her bins at the end of six weeks. Although the method is complicated, I can see the utility --- you don't overload one bin all at once, and worms can move between areas with lots of fresh food waste and areas with fresh bedding as necessary to keep themselves healthy.

Tempt

your worms to migrate to fresh bedding after six weeks.

After the first six weeks passes and each of the sections in her four

bins are full, Binet Payne rakes the contents of each bin to one side,

leaving three quarters of the bin bare. The bare part of the bin

is filled with fresh bedding and is then divided into six sections,

which she will fill with food waste in the same alternate manner she

used to fill the bin the first time. Meanwhile, worms will be

migrating out of the older composting materials and into the fresh

bedding as they finish composting the older section.

Tempt

your worms to migrate to fresh bedding after six weeks.

After the first six weeks passes and each of the sections in her four

bins are full, Binet Payne rakes the contents of each bin to one side,

leaving three quarters of the bin bare. The bare part of the bin

is filled with fresh bedding and is then divided into six sections,

which she will fill with food waste in the same alternate manner she

used to fill the bin the first time. Meanwhile, worms will be

migrating out of the older composting materials and into the fresh

bedding as they finish composting the older section.- Move nearly completed compost to the finishing bin. Five to ten days after raking the old material to one side of the bin, begin to move those castings to a finishing bin. The worms should have migrated sideways and down out of the top two inches of the old material, so you can rake that part off wth a hand rake. Wait a day and rake two more inches and repeat until you're near the bottom of the bin. The last bit of material may be chock full of worms, in which case it is scattered across the new material in the rest of the bin to speed up decomposition.

- Use castings only from the

finishing bin. The finishing bin is like another worm bin,

but the materials inside are nearly or completely done

composting. Binet Payne found that compiling all of the finished

castings into one bin made it easy for other members of the school to

use them in gardening projects and science experiments without

bothering the busy worms in active bins.

When I first read Binet

Payne's method, it felt overly complex, but as I sum it up for you, I

can see the importance of each step. For anyone who's not an

obsessive list-maker, though, I suspect this sytem would be tough to

stick to, which makes me think somebody needs to invent a system that

does all of the thinking for you. I've seen worm bins where you

fill the bottom bin up, stack on another bin which you fill up and into

which worms migrate as they finish the bottom bin, and so forth, but

this would be a very bulky system on any scale larger than a few cubic

feet. I'm sure we can come up with something better. Any

suggestions on how to scale this idea up to a farm-sized version?

When I first read Binet

Payne's method, it felt overly complex, but as I sum it up for you, I

can see the importance of each step. For anyone who's not an

obsessive list-maker, though, I suspect this sytem would be tough to

stick to, which makes me think somebody needs to invent a system that

does all of the thinking for you. I've seen worm bins where you

fill the bottom bin up, stack on another bin which you fill up and into

which worms migrate as they finish the bottom bin, and so forth, but

this would be a very bulky system on any scale larger than a few cubic

feet. I'm sure we can come up with something better. Any

suggestions on how to scale this idea up to a farm-sized version?

| This post is part of our Worm Cafe lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It was a relief to see all 6

chickens off the ground and on a roost last night.

The fact that one of our hens

is on a lower perch is more than likely some sort of expression of our

particular flock dynamics.

I suspect it's the white Cochin hen who is not letting the loner girl

play any reindeer games.

Even

though I've got some last mulching and transplanting to slip into the

early winter, we've turned a lot of our attention inside for the colder

months. One of the projects I hope to tackle is turning Mark's

old bedroom into a chicken waterer construction

room and general work space, and the first thing it needed was a big

work bench.

Even

though I've got some last mulching and transplanting to slip into the

early winter, we've turned a lot of our attention inside for the colder

months. One of the projects I hope to tackle is turning Mark's

old bedroom into a chicken waterer construction

room and general work space, and the first thing it needed was a big

work bench.

Mark's usually the

carpenter in the family, but he was nice enough not to mind me  spreading

my craftsman wings. As usual, the goal was to build something

with as little storebought materials as possible. After a bit of

poking around, I came up with a used kitchen counter (from Mark's mom

--- thanks, Rose Nell!), some used 4X4s (from my mom --- thanks, Mom!),

and some slightly used 2X4s that we'd taken out of another

project. The only really storebought component was a heaping

handful of screws, worth perhaps four dollars.

spreading

my craftsman wings. As usual, the goal was to build something

with as little storebought materials as possible. After a bit of

poking around, I came up with a used kitchen counter (from Mark's mom

--- thanks, Rose Nell!), some used 4X4s (from my mom --- thanks, Mom!),

and some slightly used 2X4s that we'd taken out of another

project. The only really storebought component was a heaping

handful of screws, worth perhaps four dollars.

I

built a box the shape of the counter out of the 2X4s, attached the 4X4s

in each corner as legs, and screwed the counter on top. Instant

work bench! Next, I plan to add a shelf underneath and a bunch

more shelves on the walls to get our tools organized and off the ground.

I

built a box the shape of the counter out of the 2X4s, attached the 4X4s

in each corner as legs, and screwed the counter on top. Instant

work bench! Next, I plan to add a shelf underneath and a bunch

more shelves on the walls to get our tools organized and off the ground.

It's hard to believe

that I didn't even know what a cordless drill was when we embarked on

this adventure four years ago. Mark has been a very patient

teacher, and has barely cringed when I broke his favorite drill bit,

sometimes offering a gentle "Are you sure you want to do it that way?",

but generally letting me make my own mistakes. Thanks, honey!

I'm ashamed to say that we

haven't done very well with our worms in the

past. Part of the problem is that we had very little waste to

give

them since nearly all of our food scraps go to the chickens, and

another part of the problem is that I didn't use optimal bedding.

From

reading Binet Payne's Worm Cafe, though, I'm also starting

to realize

that small-scale worm bins are inherently finicky, a problem that is

overcome by expanding the worm bin to compost more waste.

I'm ashamed to say that we

haven't done very well with our worms in the

past. Part of the problem is that we had very little waste to

give

them since nearly all of our food scraps go to the chickens, and

another part of the problem is that I didn't use optimal bedding.

From

reading Binet Payne's Worm Cafe, though, I'm also starting

to realize

that small-scale worm bins are inherently finicky, a problem that is

overcome by expanding the worm bin to compost more waste.

Binet Payne notes that

her 32 cubic foot worm bins are very forgiving

of environmental conditions. She places them in the shade, but

otherwise doesn't worry too much about the weather even though the bins

are located outside. When the top layer of vermicompost freezes

in the

winter, the worms just move a bit deeper into the part of the bin where

microbial decomposition warms the bedding. During the summer when

school is out, the worms do

fine coasting along on just a couple of

feedings. Not only do mid-scale worm bins provide enough castings

to actually make a dent in a homestead's needs, they are also easier to

handle.

school is out, the worms do

fine coasting along on just a couple of

feedings. Not only do mid-scale worm bins provide enough castings

to actually make a dent in a homestead's needs, they are also easier to

handle.

But where do you get ten

to twenty-five pounds of food waste per day? After failing at our

attempt to beg food waste from the local grocery store, I've got my eye

on the school down the road. I'm on the fence about whether to

try to find funding so that I could help them implement Binet Payne's

entire program (estimated cost $1,000 to $3,000), or whether I just

want to come up with air-tight containers that we could pick up on our

bi-weekly trips to town and then compost the food waste on our own

farm. I'll probably present both ideas to their principal and see

which one seems most exciting to her.

| This post is part of our Worm Cafe lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Training

chickens is a new way of learning dog training skills.

Operant conditioning from

B.F. Skinner involves a clicker and yummy snacks for reinforcement. You

can train a chicken to discriminate between shapes, navigate an

obstacle course, or just ring a bell.

I wonder if a chicken could

be trained to open and close an automatic

chicken coop door by

pushing the right button?

Does anybody reading this have an especially outrageous task they've

always wanted to train a chicken to do?

Out

of curiosity, I've had Mark keep track of how much wood he's been

splitting and stacking for our new Jotul

wood stove this

week. Even though the Jotul is very efficient, I've been very

profligate with wood, keeping the trailer perhaps ten to fifteen

degrees warmer than we did last winter with the beast, and temperatures

have been on the lower end of average outside. Even so, at the

rate we're burning, it would take us nearly two months to run through a

cord of wood. For the sake of comparison, we burned 1.75 cords of

wood in perhaps four to six weeks last year and then were cold for the

rest of the winter.

Out

of curiosity, I've had Mark keep track of how much wood he's been

splitting and stacking for our new Jotul

wood stove this

week. Even though the Jotul is very efficient, I've been very

profligate with wood, keeping the trailer perhaps ten to fifteen

degrees warmer than we did last winter with the beast, and temperatures

have been on the lower end of average outside. Even so, at the

rate we're burning, it would take us nearly two months to run through a

cord of wood. For the sake of comparison, we burned 1.75 cords of

wood in perhaps four to six weeks last year and then were cold for the

rest of the winter.

But

are we saving any time? We've discovered that it's a lot easier

to fit wood into the Jotul's smaller firebox if it's split well, and

since the fire is so easy to start I've been letting it go out a lot

and restarting it with finely split box-elder kindling. And some

of the logs are too long to fit in our new stove, so we cut them in

half with the miter saw. That's a lot more prep per log than our exterior

wood furnace

required. Even so, I estimate that Mark spent only about 15

minutes per day splitting, cutting, and hauling wood, which is probably

half the time he spent processing wood for the beast.

But

are we saving any time? We've discovered that it's a lot easier

to fit wood into the Jotul's smaller firebox if it's split well, and

since the fire is so easy to start I've been letting it go out a lot

and restarting it with finely split box-elder kindling. And some

of the logs are too long to fit in our new stove, so we cut them in

half with the miter saw. That's a lot more prep per log than our exterior

wood furnace

required. Even so, I estimate that Mark spent only about 15

minutes per day splitting, cutting, and hauling wood, which is probably

half the time he spent processing wood for the beast.

All things considered, I

think the Jotul is actually going to save us more time and money than I

initially estimated. We had been planning on a cheaper option for

the East Wing, but we're now seriously considering just saving our

pennies and buying a second Jotul.

The loner

hen now gets to sleep on

the top roost, but the trio of popular girls still won't let her perch

at their table.

I find it hard to believe

that it's December and we're still eating fresh produce for almost

every meal. I snagged these oyster mushrooms a couple of days ago

while walking Lucy --- they had sprung up on the part of the fallen

oyster mushroom log that I thought was mushroom-free and thus left

behind. Even though the mushrooms were frozen solid, they thawed

out to make tasty fajitas.

I find it hard to believe

that it's December and we're still eating fresh produce for almost

every meal. I snagged these oyster mushrooms a couple of days ago

while walking Lucy --- they had sprung up on the part of the fallen

oyster mushroom log that I thought was mushroom-free and thus left

behind. Even though the mushrooms were frozen solid, they thawed

out to make tasty fajitas.

Meanwhile, we're filling

our salad bowls with lots of lettuce and the steamer with masses of

mustard and swiss chard greens along with a weekly dose of broccoli

side florets. There are parsley and Egyptian onion tops for extra

fresh greenery, and our house is full of stored sweet potatoes, white

potatoes, butternuts, and garlic. We've still got a few ripening

tomatoes, but they're not anything to write home about.

In the interest of

variety, we've thawed out a gallon and a half of vegetables from the

freezer, but in terms of quantity, we could still be eating entirely

from the garden if we felt like it. Even though half of our fall

garden didn't germinate, the plants that did come up have given us the

tastiest early winter ever!

I think a good way to

determine if it's going to be a cold day is when our flock decides to stay in.

Today was one of those cold

days.

Although I'm sure 75% of

you know all about this, I was thrilled to be clued into one of Mark's

best tool add-ons --- the quick change adapter on the cordless

drill. This adapter hooks onto the front of the drill and allows

special drill bits and drivers to be popped in and out with a  flick

of your wrist. (To be more literal, on our drill, you just push

part of the adapter backwards and the drill bit pops out. I've

read that different brands require slightly different motions, but

they're all easy to do with your hands full.) Some other names

for the same thing include hex-shank or ultralok drill bits.

flick

of your wrist. (To be more literal, on our drill, you just push

part of the adapter backwards and the drill bit pops out. I've

read that different brands require slightly different motions, but

they're all easy to do with your hands full.) Some other names

for the same thing include hex-shank or ultralok drill bits.

With a quick change

adapter in place, it's simple to swap back and forth between drilling

pilot holes and then driving in the screw. The only problem is

that you have to use special bits with a hexagonal (rather than round)

base, so if you lose your favorite snap-in drill bit, you might spend

as long looking for it as you would have swapping between the drill bit

and the phillips head driver. Maybe once all of our tools are

organized, we won't have this problem any more?

Ice and Easy de-icer

+ 4 feet of Reflectix=

Experimental chicken water heater.

We'll know in the morning if

this will be good enough to keep the automatic chicken nipple from

freezing.

My

maternal grandfather died when I was six, so I can't actually remember

anything about him. But lately I've realized that I probably get

my obsessive list-making from Grandpa Eckberg.

My

maternal grandfather died when I was six, so I can't actually remember

anything about him. But lately I've realized that I probably get

my obsessive list-making from Grandpa Eckberg.

I also inherited this

little red bookcase from him. The story goes that Grandpa made

this bookcase out of orange crates while he and his family were

stationed in California during World War II. Were the wooden

orange crates disposable, a slightly more sturdy version of the half

bushel cardboard boxes of oranges you can buy today? Was Grandpa

reusing the wood because he couldn't bear to throw the boxes away, or

was it just an example of Yankee frugality? Either way, I figured

that Grandpa wouldn't mind me adding a couple of extra shelves and a

back to his bookcase to make it easier to fill up with containers of

screws.

The

pile of miscellaneous stuff awaiting organization in the middle of our

office doesn't seem to be getting any smaller, but the space is already

easier to use. This photo of Mark working on our homemade chicken

waterers doesn't

look like much, but you have to realize that just a year and a half ago

Mark was making waterers under a tent in the backyard. When you

start with nothing, every little improvement is exciting.

The

pile of miscellaneous stuff awaiting organization in the middle of our

office doesn't seem to be getting any smaller, but the space is already

easier to use. This photo of Mark working on our homemade chicken

waterers doesn't

look like much, but you have to realize that just a year and a half ago

Mark was making waterers under a tent in the backyard. When you

start with nothing, every little improvement is exciting.

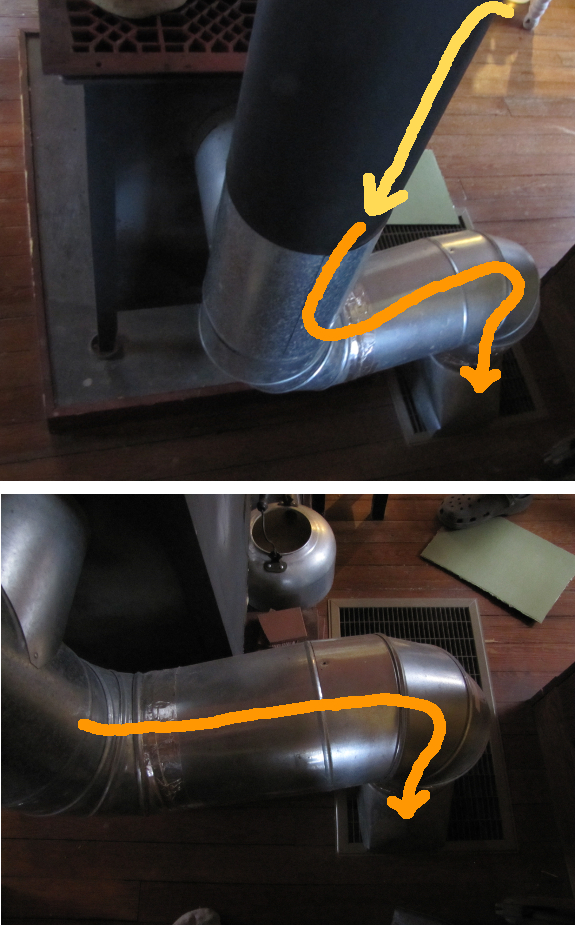

The Ice

and Easy did a good job keeping the water from freezing in the

bucket, but last night it got down to 17 degrees farenheit, which

equaled frozen chicken nipples this morning.

They both thawed out this

afternoon when the temperature got around 25 degrees.

I installed a light with

another layer of Reflectix to keep some of the heat within the nipple

drinking area. We'll see tomorrow morning if this is enough to keep

water flowing during this sub freezing cold spell.

Do

you

remember learning in high school biology class about mitochondria,

those tiny organelles inside your cells which convert sugars into

energy? Remember how they fold their cell membranes up into a

convoluted mass to provide surface area for all those reactions?

That's what I've been thinking about all week as I add surface area

(aka shelves) to the office, turning it into the powerhouse of the

trailer.

Do

you

remember learning in high school biology class about mitochondria,

those tiny organelles inside your cells which convert sugars into

energy? Remember how they fold their cell membranes up into a

convoluted mass to provide surface area for all those reactions?

That's what I've been thinking about all week as I add surface area

(aka shelves) to the office, turning it into the powerhouse of the

trailer.

My most recent addition

is a homemade bookcase, sized just right to fit

into that difficult spot beside the door. Although not as elegant

as Grandpa's

bookcase, it will

hold twice as many odds and ends.

Yes, scary pile in the middle of the floor, I'm talking about you.

It works!

Now I need to simplify the

design. Maybe have the light automatically switch off during the day

and when it's above freezing, or experiment with Roland's

idea of applying heat through an electrical current directly to the

nipple in question.

Visit our heated

chicken waterer page for more details on designing your own.

Once

I started damping our Jotul

F 602 wood stove

down at night, I realized that the stove makes copious amounts of first

class charcoal. Thirteen days of fires filled up our bucket

beyond the brim --- time to figure out how to filter the charcoal from

the ash.

Once

I started damping our Jotul

F 602 wood stove

down at night, I realized that the stove makes copious amounts of first

class charcoal. Thirteen days of fires filled up our bucket

beyond the brim --- time to figure out how to filter the charcoal from

the ash.

Both wood ashes and

charcoal are good for the garden, but they have different uses.

Ash is high in potassium, and also contains quite a bit of phosphorus,

magnesium, and various trace minerals. More important, though,

wood ashes are a quarter to a half calcium carbonate (aka "lime"), so

you have to be aware that you will raise the pH of your soil by

applying the ashes. Since our soil already has a pH around 6 and

our potassium levels are naturally very high, I don't want to apply too

much ash or I'll raise the pH above the optimal 6.5 recommended for a

vegetable garden and possibly bring the potassium up to toxic levels.

The charcoal is what I'm

really excited about. We've been sold on the benefits of

biochar to soil,

but haven't

been ready to put in the time to build a biochar production

chamber. Sure is nice of the airtight wood stove to do that job

for us while also producing plenty of heat to keep my toes warm.

I built a sifting box to

separate the charcoal from the ashes, a process that went pretty

smoothly but needs a bit of tweaking. First of all, even though

the coals had been sitting in the ash bucket for nearly twelve hours,

some were still burning, and I scorched the wood  on

the inside of my sifter. Mark suggested adding flashing to the

inside, which is a great idea. The job was also pretty messy, with ash flying everywhere --- maybe I need to add a lid to the top of the sifter?

on

the inside of my sifter. Mark suggested adding flashing to the

inside, which is a great idea. The job was also pretty messy, with ash flying everywhere --- maybe I need to add a lid to the top of the sifter?

Despite needing some

optimizing, the sifting operation went quickly once I realized I should

only dump in about four inches of stove debris at a time and jiggle the

sifter a lot to get the ashes to fall through the holes. The

really difficult bit will be figuring out how to crush the biochar into

powder. We could use the chunks as they are, but my understanding

is that we get more surface area and more microbial action if we crush

the biochar into much smaller pieces. While we put our thinking

caps on, I'll be storing our charcoal in a metal container so that it

can't burn through the bottom and start a fire.

Going

up our little hill to fetch 3 pails of water takes about 5 minutes once

you break a hole in the top layer of ice in the tank.

Going

up our little hill to fetch 3 pails of water takes about 5 minutes once

you break a hole in the top layer of ice in the tank.

While I'm doing this I often

compare it to the early days of getting water from the creek where the

main problem was finding a deep enough spot so the bucket would mostly

fill up.

I estimate this tank method

is 4 to 5 times faster and easier.

We've

been operating under deep freeze conditions all week. Friday

night, the snow started falling, and by the end of the weekend we had

about four inches. Then the temperatures dropped way down, with

days below freezing and nights in the teens and single digits.

For the sake of comparison, December's average high is 48 and our

average low is 26 --- waking up to ice in my water bottle inside the

trailer is highly unusual, but that's what Thursday morning was like.

We've

been operating under deep freeze conditions all week. Friday

night, the snow started falling, and by the end of the weekend we had

about four inches. Then the temperatures dropped way down, with

days below freezing and nights in the teens and single digits.

For the sake of comparison, December's average high is 48 and our

average low is 26 --- waking up to ice in my water bottle inside the

trailer is highly unusual, but that's what Thursday morning was like.

Even though our water

line is buried to within four feet of the house, we didn't finish it up

because of a

kink in the plan.

Usually, a frozen water line isn't a big deal --- you fill up a few

pots with wash water and a few jugs with drinking water, and the line

thaws out in the afternoon a day or two later. Not this

week. Instead, it stayed so cold that the snow sat on the ground

and the line stayed frozen solid until Mark

busted some ice out of the thousand gallon tank to carry wash water to

the house.

The positive part of

this deep freeze is that it's been a real test of our other winter

projects. Mark's homemade

heated chicken waterer was still operating on a 9 degree Fahrenheit

morning, which is just about as cold as it ever gets around here.

And when the snow finally melted enough that I could pull back the row

covers in the mule garden, I was able to pick fresh, beautiful mustard

greens for our lunch.

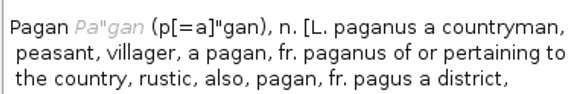

The enclosed pet

porch suffered a set back this week when water leaked in and formed

a solid sheet of ice on the floor.

I decided to use some

Reflectix to block the water path, which should also help to hold in

some heat if one or both of the cats decide they want to sleep there.

They've both figured out how

to use it and seem to like the new freedom.

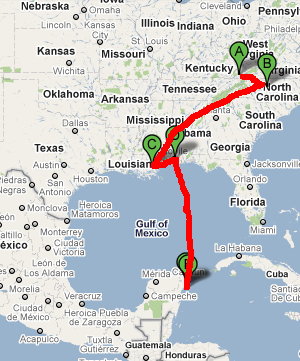

Last

year's honeymoon

cruise to the Yucatan

exceeded my wildest

expectations, so we decided we had to give it another shot, but a

little later in the year once the garden was sound asleep. This

evening, we'll be taking the train south, then jumping aboard a cruise

ship to drift through the Gulf of Mexico, explore Mayan ruins, and

experience a Mayan steam lodge. So, for all of those people who

would usually call me on my birthday, please send me an email instead

--- I'll be away from the phone and having a blast!

Last

year's honeymoon

cruise to the Yucatan

exceeded my wildest

expectations, so we decided we had to give it another shot, but a

little later in the year once the garden was sound asleep. This

evening, we'll be taking the train south, then jumping aboard a cruise

ship to drift through the Gulf of Mexico, explore Mayan ruins, and

experience a Mayan steam lodge. So, for all of those people who

would usually call me on my birthday, please send me an email instead

--- I'll be away from the phone and having a blast!

One of our readers ---

Shannon --- kindly offered to mind the homestead

while we're sunning ourselves in Mexico, and once I learned the sheer

quantity of firepower he possesses, we couldn't turn him down.

Mark felt better about me announcing to the world that we'd be away

from home once he saw Shannon's arsenal. Don't have a heart

attack, Mom, he's a nice guy despite the guns! Single female

readers, Shannon is available and a very hearty woodchopper --- very

good farm-husband material.

The real point of this post

(there's a point?) is to let you know that

our internet access will be spotty over the next week and a half, so

your comments might languish for a while in moderation. We've

saved up a bunch of fun posts to tide you over until we return to the

homestead, but my crontab syntax needs a bit of work, and there's a

chance my auto-posts just won't go through --- I apologize in advance

if you have to go a day without the Walden Effect. Please do keep

commenting as usual --- I love coming home to tidbits of information

from our loyal readers. Have a great solstice!

The real point of this post

(there's a point?) is to let you know that

our internet access will be spotty over the next week and a half, so

your comments might languish for a while in moderation. We've

saved up a bunch of fun posts to tide you over until we return to the

homestead, but my crontab syntax needs a bit of work, and there's a

chance my auto-posts just won't go through --- I apologize in advance

if you have to go a day without the Walden Effect. Please do keep

commenting as usual --- I love coming home to tidbits of information

from our loyal readers. Have a great solstice!

We

finally got around to killing one of our hens who hadn't laid an egg

since the spring. After a couple of months by herself with top

notch food, I determined that she had developed a defective

shell gland that wouldn't heal and that she needed to be culled

from the flock. You might be interested in reading my post over

on our chicken blog about my philosophy on when

to cull chickens from your flock.

We

finally got around to killing one of our hens who hadn't laid an egg

since the spring. After a couple of months by herself with top

notch food, I determined that she had developed a defective

shell gland that wouldn't heal and that she needed to be culled

from the flock. You might be interested in reading my post over

on our chicken blog about my philosophy on when

to cull chickens from your flock.

I'm

ashamed to say that I procrastinated all fall and never put the hen's

demise on our list until the end of November. Those five minutes

a day I spent giving her individualized attention and the cup of food

per day she ate while laying no eggs really adds up, and I hope that

I've learned my lesson not to procrastinate in the future. After

all, it took less than an hour of concerted attention to dispatch,

pluck, and gut her.

I'm

ashamed to say that I procrastinated all fall and never put the hen's

demise on our list until the end of November. Those five minutes

a day I spent giving her individualized attention and the cup of food

per day she ate while laying no eggs really adds up, and I hope that

I've learned my lesson not to procrastinate in the future. After

all, it took less than an hour of concerted attention to dispatch,

pluck, and gut her.

Usually,

I would turn an old hen into potstickers or

another sausage-type dish, but I was a bit worried about the condition

of this hen's meat. As soon as we slit her throat, fecal matter

came bubbling up from her crop, and it was impossible to keep the

manure off the meat. I assume there was some kind of physical

blockage inside her, which contributed to her egg-laying problem, but I

just didn't feel good about eating the questionable meat. So we

cut her into quarters as a winter treat for Lucy, who wants all dog

owners to know that uncooked poultry bones are a

perfectly safe (and very nutritious) addition to the canine diet.

Usually,

I would turn an old hen into potstickers or

another sausage-type dish, but I was a bit worried about the condition

of this hen's meat. As soon as we slit her throat, fecal matter

came bubbling up from her crop, and it was impossible to keep the

manure off the meat. I assume there was some kind of physical

blockage inside her, which contributed to her egg-laying problem, but I

just didn't feel good about eating the questionable meat. So we

cut her into quarters as a winter treat for Lucy, who wants all dog

owners to know that uncooked poultry bones are a

perfectly safe (and very nutritious) addition to the canine diet.

I'm not sure how practical this chicken coop is, but it sure impresses

me with its sleek design and egg like curves.

It's called the Nogg, and it has wheels hidden

underneath and is made from cedar.

The website doesn't list the

price, which I assume is because it costs a small fortune.

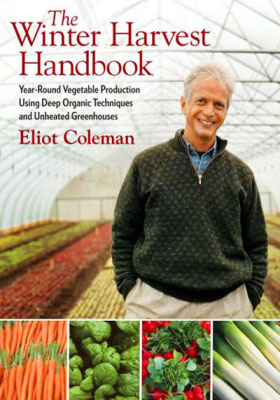

In 1968, Eliot Coleman (quite

literally) bought Helen and Scott

Nearings'

back 40 acres and started farming. His farm is on the

coast of Maine --- zone 5 --- where many people think growing

conditions are tough for even producing a summer crop. But

Coleman didn't want to think so small. Instead, he dreamed of

developing a low tech and economical way to harvest fresh vegetables

year round. The

Winter Harvest Handbook

is a beautifully illustrated and clearly written guide that sums up

forty years of gardening experience and tells precisely how to harvest

salad greens and a few other crops all winter long.

In 1968, Eliot Coleman (quite

literally) bought Helen and Scott

Nearings'

back 40 acres and started farming. His farm is on the

coast of Maine --- zone 5 --- where many people think growing

conditions are tough for even producing a summer crop. But

Coleman didn't want to think so small. Instead, he dreamed of

developing a low tech and economical way to harvest fresh vegetables

year round. The

Winter Harvest Handbook

is a beautifully illustrated and clearly written guide that sums up

forty years of gardening experience and tells precisely how to harvest

salad greens and a few other crops all winter long.

Coleman started his

journey by looking into the past. 150 years ago, Parisian farmers

(maraichers)

grew all of the city's vegetables and even exported some to England

using just 6% of the city's land area as growing space. Their

highly intensive

gardens depended on copious amounts of horse manure from the city

stables --- sometimes as much as 400 tons per acre. (For the sake

of comparison, Lee

Reich's mulch campaign,

which I thought was beyond my ability to achieve, used only about 90

tons of organic matter per acre,  assuming

a conversion rate of about 1350 pounds per cubic yard.) This

French manure was used fresh as the heat source in hotbeds for winter

growing, with panes of glass over the top and then a mat of straw for

additional night-time insulation as needed. They also used

thousands of glass cloches (bottomless jars) to protect individual

plants.

assuming

a conversion rate of about 1350 pounds per cubic yard.) This

French manure was used fresh as the heat source in hotbeds for winter

growing, with panes of glass over the top and then a mat of straw for

additional night-time insulation as needed. They also used

thousands of glass cloches (bottomless jars) to protect individual

plants.

The French intensive

gardening system was clearly successful, but it

was also hugely labor-intensive. The hotbeds and cloches could

overheat on sunny days, so farmers would spend hours walking down the

rows and manually propping them open in the morning, then closing each

one back up as the sun fell at night. Modern winter-growers have

replaced all of this labor with high tech thermostats and self-opening

vents and fans, but Coleman wanted to find a system somewhere in the

middle. This week's lunchtime series details his method that

combines the simplicity of the French system with enough modern

conveniences to let you grow winter greens without quite so much

back-breaking labor.

| This post is part of our Winter Harvest Handbook lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

A

few years ago, I decided to figure out which winter squash suited our

tastebuds and garden the best, so I tested out Baby Bear, Howden, and

Jack-o-lite Pumpkins, Butternut Squash, Royal Acorn Squash, and

Cushaw. They all produced something, but the Cushaw was

definitely the most productive in terms of pounds of vegetables per

vine while Butternuts were quickly decided to be the taste test winner.

A

few years ago, I decided to figure out which winter squash suited our

tastebuds and garden the best, so I tested out Baby Bear, Howden, and

Jack-o-lite Pumpkins, Butternut Squash, Royal Acorn Squash, and

Cushaw. They all produced something, but the Cushaw was

definitely the most productive in terms of pounds of vegetables per

vine while Butternuts were quickly decided to be the taste test winner.I have a bit of a French mindset when it comes to food --- I believe that we should eat what tastes good, but consider high carb foods to be a treat to be eaten in small quantities now and then. We'd much rather eat a butternut pie once a week than a pumpkin pie twice a week because the former is just so much tastier! As a result, we haven't grown pumpkins since our trial year, and have found that butternuts are seldom bothered by pests or diseases.

If

you're bound and determined to grow pumpkins, though, I have a few

words of advice from fighting my own battles to grow summer squash

here. The first step is to figure out what's killing your

pumpkins. Is it one of the fungi or bacteria which love moist

conditions? If so, plant your pumpkins far apart in the sunniest

spot like

we do with our tomatoes so that they dry out quickly

after rains. Or are your pumpkins succumbing to the squash vine

borer, which is our

personal bane? Variety selection seems to be your best bet when

fighting the vine borer, so try a half dozen types this year and see

which one does best. Good luck!

If

you're bound and determined to grow pumpkins, though, I have a few

words of advice from fighting my own battles to grow summer squash

here. The first step is to figure out what's killing your

pumpkins. Is it one of the fungi or bacteria which love moist

conditions? If so, plant your pumpkins far apart in the sunniest

spot like

we do with our tomatoes so that they dry out quickly

after rains. Or are your pumpkins succumbing to the squash vine

borer, which is our

personal bane? Variety selection seems to be your best bet when

fighting the vine borer, so try a half dozen types this year and see

which one does best. Good luck! The heart of Eliot Coleman's

winter gardening is a two-tiered method of protecting the plants from

winter cold. He grows his vegetables under floating row covers

inside simple greenhouses (hoop houses), and the combination of the two

is the equivalent of moving his garden 1,000 miles south to where it is

three climatic zones warmer. The majority of his growing area ---

and the part I will be discussing in this lunchtime series --- is

completely unheated, but he does note that for some people who have a

cheap source of heat, it might be worthwhile to warm the greenhouses

until they stay just above freezing.

The heart of Eliot Coleman's

winter gardening is a two-tiered method of protecting the plants from

winter cold. He grows his vegetables under floating row covers

inside simple greenhouses (hoop houses), and the combination of the two

is the equivalent of moving his garden 1,000 miles south to where it is

three climatic zones warmer. The majority of his growing area ---

and the part I will be discussing in this lunchtime series --- is

completely unheated, but he does note that for some people who have a

cheap source of heat, it might be worthwhile to warm the greenhouses

until they stay just above freezing.

I've always been leery

of hoop houses and greenhouses because of

disease and pest buildup, and Eliot Coleman notes that permanent

greenhouses also have the side effect of building up soil nutrients to

poisonous levels. By cutting your growing space off from the

outside world, you're promising to keep the ecosystem in balance, which

is a tough job when we haven't even identified all of the

microorganisms at work in our soil. Coleman has a solution ---

let nature do that hard work for you. His greenhouses are light

enough that his tractor can pull them to a new patch of ground a couple

of times a year, allowing nature to heal the wacky greenhouse ecosystem

left behind. His movable greenhouses also have the side benefit

of allowing him to grow heat-loving summer crops in the greenhouse

until late October, then move the greenhouse onto two-month-old fall

crops just as the killing frosts commence --- in essence, he gets

fourteen months of greenhouse time per year for each structure.

The row covers Coleman

uses inside his greenhouse are the same

spun-bonded fabric you can purchase in many seed catalogs and which

you'll see in my garden. (He uses Agribon brand row covers from

Johnny's.) Since the greenhouse blocks wind and heavy weather,

you can simply drape your row covers over twelve inch tall wickets made

of #9 wire and spaced every four feet along the bed. Snap a few

clothespins on to hold the fabric in place, and you're done with your

second tier of protection. Unlike glass-topped cold frames or

cloches, row cover fabric is self-venting and only needs to be removed

when warm spring days in March begin to overheat your crops.

I was glad to see that

Coleman did some research to determine the best

kind of row cover since I've been confused by all the choices in the

past. Your first decision is whether to choose polyvinyl alcohol

fabric or the simple spun-bonded fabric which is more readily

available. The former has marked advantages of lasting about four

times as long, allowing 90% of light to pass through (versus 30 to

85%), and keeping the air underneath about one degree warmer, but with

a price tag five times higher, polyvinyl alcohol probably isn't worth

it.

I was glad to see that

Coleman did some research to determine the best

kind of row cover since I've been confused by all the choices in the

past. Your first decision is whether to choose polyvinyl alcohol

fabric or the simple spun-bonded fabric which is more readily

available. The former has marked advantages of lasting about four

times as long, allowing 90% of light to pass through (versus 30 to

85%), and keeping the air underneath about one degree warmer, but with

a price tag five times higher, polyvinyl alcohol probably isn't worth

it.

Next choice is --- light

fabric or heavy fabric? In the seed

catalogs, you'll see the heavy fabrics listed as protecting your plants

several degrees colder, but in Coleman's experience, these heavy

fabrics block so much of the sun's light that the ground actually ends

up colder in the long run. Instead, he recommends the thinnest

row covers, which are rated as protecting your plants only down to 28

degrees Fahrenheit, but which Coleman said provide increasing amounts

of protection as the weather gets colder.

I won't go into the

specifics of Coleman's greenhouse construction

since his scale of greenhouse --- 48 feet by 22 feet --- is beyond the

scope of our homestead garden. If you want to know more, check

his book out of the local library, or visit his website (from which I snagged these

photos.) Or stay tuned for tomorrow's

post, in which I'll consider ways to apply Coleman's method to the

backyard.

This post is part of our Winter Harvest Handbook lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Winter Harvest Handbook lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

When

we embarked on the East Wing project, Mark floated the idea of using a

bit of the extra space opened up in the trailer to put in a modern

washing machine. At first, the idea seemed okay, but the more I

thought about it, the more I clung to my wringer

washer.

When

we embarked on the East Wing project, Mark floated the idea of using a

bit of the extra space opened up in the trailer to put in a modern

washing machine. At first, the idea seemed okay, but the more I

thought about it, the more I clung to my wringer

washer.

On summer days, doing

laundry in the wringer washer is pure joy.

I sink my hands in the soapy water to pull out a shirt, pass it through

the wringer into the rinse water, then back through the wringer into

the laundry basket. Later, I hang up the load in the sunniest

spot of the yard, shared by our three bee hives, and the workers come

to explore the damp clothing. Now and then, a guard bee gets

pissed off at me working five feet from her door and she buzzes me

until I back off a bit, before trying again.

In

the winter, laundry can be a bit tricky, but the experience is almost more enjoyable.

Once the laundry basket starts to fill up, I scan the ten day weather

forecast looking for the most sunny, beautiful day. Here in zone

6, there's generally at least one beautiful day per

month, even in the dead of winter, and looking forward to laundry on

that day makes it extra special. Since we dry our clothes

on the line, we need that warm day anyway to suck moisture from the

clean clothes, and I suspect that if we got a washing machine, I'd soon

be ignoring the weather and buying a drier. Meanwhile, wringing

each piece of clothing by hand reminds me to wear our clothes

until they're truly dirty rather than dropping a clean sweather in the

laundry basket after one light wearing. Plus, the wringer washer

drains completely by gravity, so it can be left outside all winter

rather than taking up heated space in the house.

In

the winter, laundry can be a bit tricky, but the experience is almost more enjoyable.

Once the laundry basket starts to fill up, I scan the ten day weather

forecast looking for the most sunny, beautiful day. Here in zone

6, there's generally at least one beautiful day per

month, even in the dead of winter, and looking forward to laundry on

that day makes it extra special. Since we dry our clothes

on the line, we need that warm day anyway to suck moisture from the

clean clothes, and I suspect that if we got a washing machine, I'd soon

be ignoring the weather and buying a drier. Meanwhile, wringing

each piece of clothing by hand reminds me to wear our clothes

until they're truly dirty rather than dropping a clean sweather in the

laundry basket after one light wearing. Plus, the wringer washer

drains completely by gravity, so it can be left outside all winter

rather than taking up heated space in the house.

I know that Mark was

trying to save me work by offering a modern

washing machine, but right now I feel like I don't want to set foot on

that slippery slope. Maybe I'll change my tune in February....

Eliot

Coleman's method of growing winter crops under row covers inside

unheated greenhouses clearly works like a charm for the market

gardener, but can those of us just growing for ourselves follow

suit? First of all, Coleman writes that true southerners (those

in zones 8 and 9) can probably get away with growing winter crops under

just row covers, and my father's experience in South Carolina bears

that out. And Coleman also presents a simpler alternative that

may provide all the protection we would need here in zone 6 --- quick

hoops.

Eliot

Coleman's method of growing winter crops under row covers inside

unheated greenhouses clearly works like a charm for the market

gardener, but can those of us just growing for ourselves follow

suit? First of all, Coleman writes that true southerners (those

in zones 8 and 9) can probably get away with growing winter crops under

just row covers, and my father's experience in South Carolina bears

that out. And Coleman also presents a simpler alternative that

may provide all the protection we would need here in zone 6 --- quick

hoops.

Coleman makes his quick

hoops by bending ten foot lengths of 1/2" electrical conduit into half

circles, then sinking ten inches of each end into the ground so that

the hoop covers an area about six feet wide. After placing a hoop

every five feet along the rows, he covers them with ten foot wide

sections of row cover which are weighed down on the edges with

sandbags. Once very cold weather threatens, he adds a sheet of

plastic on top (primarily to shed snow?)

In effect, Coleman's quick

hoops are a combination of a floating row cover and a hoop house.

He notes that a quick hoop costs only 5% as much as the same square

footage of greenhouse and protects low-growing overwintering crops like

onions, spinach, and lettuce so that they can be harvested very early

in the spring on his farm in Maine.

In effect, Coleman's quick

hoops are a combination of a floating row cover and a hoop house.

He notes that a quick hoop costs only 5% as much as the same square

footage of greenhouse and protects low-growing overwintering crops like

onions, spinach, and lettuce so that they can be harvested very early

in the spring on his farm in Maine.

I'm tempted by his quick

hoop concept much more than by his larger scale greenhouses, but I have

a few reservations. First of all, I'm not thrilled by the

recurring cost of buying row cover fabric --- under heavy use, it tends

to last only a year or two. On the other hand, I could cover most

of the mule garden with row cover fabric for only $40, which would

probably be about equivalent to the cost of cooling that amount of

summer produce over the winter in the freezer. The sticking point

would be whether our cats and dog love jumping on the quick hoops and

tearing them to pieces as much as they love ruining my cold frames ---

if so, buying row cover fabric multiple times a year just wouldn't be

worth it.

The other question is

--- are quick hoops enough to protect a winter harvest here in chilly

zone 6? Coleman didn't seem to think so, but he also advocated

using the lowest tech solution first to try it out before moving up to

more expensive solutions, so I think he would approve of us trying

quick hoops on our farm.

| This post is part of our Winter Harvest Handbook lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

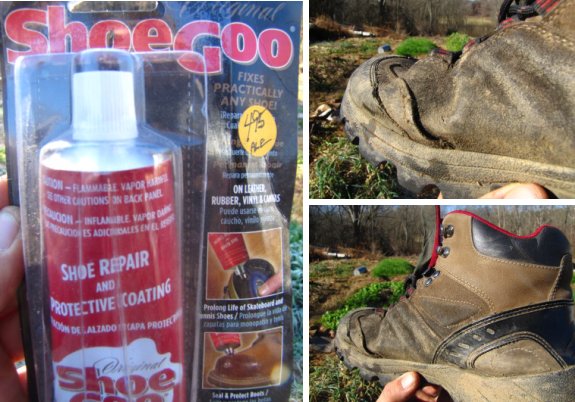

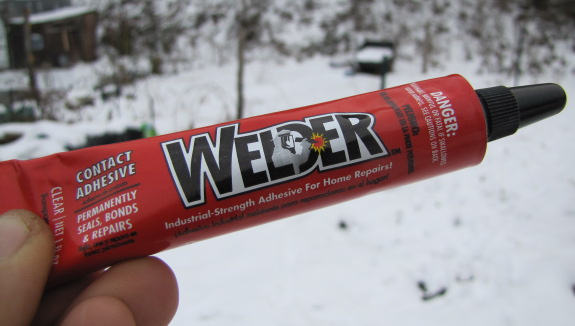

The work load here on Wetknee

farm has proven to be rough on work boots.

I thought an expensive pair

of Timberlands would last

longer. Turns out they started to fail within the same time frame as

cheaper boots which prompted me to keep going with Ozark Trail, which usually sells

for 30 dollars but can sometimes be found for 20.

The weak point is always

where my toes bend. This time I tried to extend the life of the above

pair with a product called Shoe Goo.

I made sure they were nice and dry and applied a liberal amount within

the gaps and gave it the full 48 hours of set up time.

My feet got wet the first day

just by stepping in puddles while chopping wood.

I think this product would

work well if you needed to re-attach the sole to the shoe as pictured

on the package. It might even form a decent protective coating to seal

up some shoes, but I don't think it's up to the task of bringing back

footwear that is so far gone they get your socks wet everytime you

cross the creek.

After

years of experimentation, Eliot Coleman concluded that most plants stop

growing when the day length drops below 10 hours. After this

time, even if you protect your vegetables from the cold, they are

merely existing in a semi-hibernatory state.

After

years of experimentation, Eliot Coleman concluded that most plants stop

growing when the day length drops below 10 hours. After this

time, even if you protect your vegetables from the cold, they are

merely existing in a semi-hibernatory state.

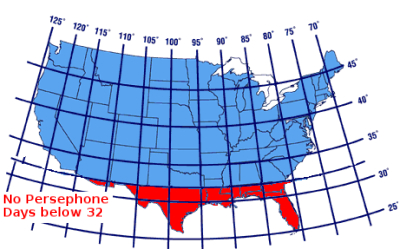

Coleman coined the term

"Persephone Days" to refer to this deep winter

period of short days, which occurs from November 5 to February 5 on his

farm in Maine, from December 1 to January 10 in Charlotte, North

Carolina, and from about November 22 to January 19 here in southwest

Virginia. Those of you who are lucky enough to live south of the

32nd parallel have no Persephone Days and can keep your crops active

all winter if you play your cards right.

The trick to a long

winter harvest is to plant your crops at just the

right stage of the late summer and fall so that they are just shy of

maturity when the Persephone Days begin. Young plants are much

hardier than older ones, so planting dates are even more important in

the fall than in the spring --- planting too early is just as bad as

too late. You'll also need to pay close attention to succession

planting so that you'll have a continuous harvest throughout the winter

rather than a mass of lettuce one week and then no more for the rest of

the year. In effect, you're not extending the growing season,

just the harvest season.

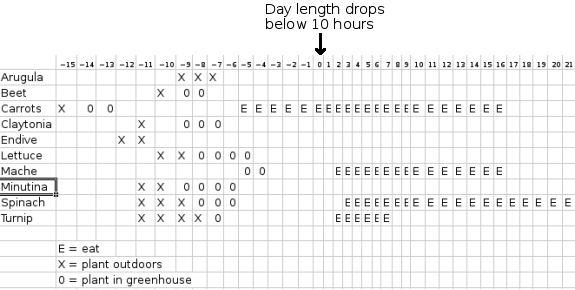

I mocked up the chart

above based on information in The

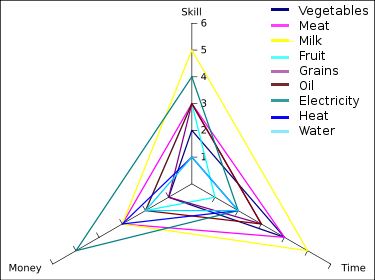

Winter Harvest Handbook,

but converted it over to the type of planting calendar I find so

helpful. Rather than placing the last or first frost date

at 0 the way I do with my spring

planting and fall planting

calendars,

I've placed the onset of the Persephone Days there, but the chart is

otherwise read in the same manner. For example, Eliot Coleman's

Persephone Days begin November 5, so he plants his first arugula nine

weeks before, around September 3. Since my Persephone Days begin

on November 22, I should plant my first arugula on September 20.

You'll also notice that

Coleman lists outdoors and greenhouse planting

times for many of his crops. As I mentioned in a previous post,

the greenhouse crops don't really need to be covered for a couple of

months in many cases, so his "greenhouse-planted" carrots seeded

fourteen weeks before his Persephone Days are actually planted in

the open, then have a greenhouse moved over top of them in late

October.

You'll also notice that

Coleman lists outdoors and greenhouse planting

times for many of his crops. As I mentioned in a previous post,

the greenhouse crops don't really need to be covered for a couple of

months in many cases, so his "greenhouse-planted" carrots seeded

fourteen weeks before his Persephone Days are actually planted in

the open, then have a greenhouse moved over top of them in late

October.

A word of warning ---

all of Coleman's data is for the far

northeast, so I expect I'll need to play around with these planting

dates by as much as a week or two to find the optimal planting times

for my climate. If you've already developed a planting calendar

for winter harvest in the southeastern or mid-Atlantic states, I'd be

curious to hear your specifics.

| This post is part of our Winter Harvest Handbook lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I'd

heard tidbits of Eliot

Coleman's wisdom

secondhand, which is what tempted me to plant

extra mustard greens and leave them be through the fall in hopes of a

winter harvest.

I planted several beds on August 20, then planted more on September

9. Both sets of greens grew beautifully, but the August-planted

mustard greens reached and passed peak maturity before our Persephone

Days began, and soon

the oldest greens were absolutely loaded with aphids.

I'd

heard tidbits of Eliot

Coleman's wisdom

secondhand, which is what tempted me to plant

extra mustard greens and leave them be through the fall in hopes of a

winter harvest.

I planted several beds on August 20, then planted more on September

9. Both sets of greens grew beautifully, but the August-planted

mustard greens reached and passed peak maturity before our Persephone

Days began, and soon

the oldest greens were absolutely loaded with aphids.

I subscribe to the

belief that insect infestations are a sign that I'm doing something

wrong, especially when it comes to aphids. The question is, which

of the three factors that separate the aphid-covered greens from the

healthy greens is the cause of the infestation?

- Early planting --- Eliot

Coleman advises that crops for winter harvest should just be reaching

maturity as the Persephone Days begin, and the buggy mustard was

overmature. Mustard in the later-planted beds is aphid-free and

vibrant.

- Protected microclimate

--- I used row cover fabric over the buggy plants earlier than I used

it over the non-buggy plants. I wonder if the fabric helped the

aphids survive freezing temperatures.

Poor soil and shade --- Even though all

of the aphid-coated mustard was planted early, one early-planted bed

skipped the aphid infestation. The buggy beds are at the west end

of the mule garden where they get more shade and where the soil is much

thinner --- the plants were probably already struggling a bit before

the aphids moved in. The happy but elderly mustard is in the

better soil of the east end of the mule garden and receives the most

winter sun.

Poor soil and shade --- Even though all

of the aphid-coated mustard was planted early, one early-planted bed

skipped the aphid infestation. The buggy beds are at the west end

of the mule garden where they get more shade and where the soil is much

thinner --- the plants were probably already struggling a bit before

the aphids moved in. The happy but elderly mustard is in the

better soil of the east end of the mule garden and receives the most

winter sun.

Since I don't know which

factor is the primary cause of my aphid infestation, I'll try to

correct all three for next year. Meanwhile, I've discovered that

you don't even notice the aphids once the greens are cooked --- extra

protein.

Eliot

Coleman experimented with dozens of

types of cool season vegetables to discover the ones that work best for

winter harvest. His overall winner --- and the crop to which he

devotes half of his greenhouse space during the cold season --- is spinach. I've played with

spinach a bit and ended up mainly deleting it from our cycle since I

felt it wasn't as cold hardy as kale, the leaves were slow to pick

compared to other greens, and its germination can be quite

spotty. However, spinach has the benefit of being willing to put

out new leaves all winter, while even the most cold hardy crucifers

like kale just sit dormant during the darkest months. Clearly,

spinach is worth another try.

Eliot

Coleman experimented with dozens of

types of cool season vegetables to discover the ones that work best for

winter harvest. His overall winner --- and the crop to which he

devotes half of his greenhouse space during the cold season --- is spinach. I've played with

spinach a bit and ended up mainly deleting it from our cycle since I

felt it wasn't as cold hardy as kale, the leaves were slow to pick

compared to other greens, and its germination can be quite

spotty. However, spinach has the benefit of being willing to put

out new leaves all winter, while even the most cold hardy crucifers

like kale just sit dormant during the darkest months. Clearly,

spinach is worth another try.

Coleman's other top

winter crops are listed below:

Mache

is a hardy salad

green that grows all winter like spinach. Unlike spinach, though,

you have to succession plant mache since you harvest the entire plant

rather than snipping off leaves.

Mache

is a hardy salad

green that grows all winter like spinach. Unlike spinach, though,

you have to succession plant mache since you harvest the entire plant

rather than snipping off leaves.- Leeks are a year-round crop for Coleman. I consider leeks too nitpicky for our garden when we can get the same results with less work using Egyptian onions, but The Winter Harvest Handbook reminded me that growing Egyptian onions inside a quick hoop would probably turn this nearly evergreen crop into a true all-winter producer.

- Claytonia is another very cold-hardy salad green.

- Asian greens --- specifically mizuna, mibuna, tatsoi, pak choi, and tokyo bekana --- are among Coleman's favorites, again due to their hardiness.

- Lettuce is listed as less hardy than many of the other crops, making me think that we could extend our winter salad season by a month or two just by swapping crops. Although lettuce has no problem growing with only eight hours of sunlight per day, cool soil temperatures slow it down considerably.

Kale can

be used as both

a salad green (for which he prefers Dwarf Scotch Curled Kale) or as a

cooking green (for which he prefers Tuscan Kale.)

Kale can

be used as both

a salad green (for which he prefers Dwarf Scotch Curled Kale) or as a

cooking green (for which he prefers Tuscan Kale.)- Carrots are part of his fresh-from-the-garden harvest from October through February. Although they can keep longer, he's noticed (as have I) that once the top growth begins in the spring, the flavor declines markedly. Coleman plants Napoli for winter harvest, then another crop of Nelson carrots in late December for an early spring crop.

- Turnips are a favorite of his customers, so he grows them even though they only last until Christmas in his greenhouse. Hakurei is his favorite variety for sweet roots and tasty greens.

As you can see, the

majority of the winter harvest is salad and cooking

greens, but anything fresh from the garden tastes better than the most

carefully frozen summer bounty by February. I've read blogs of

homesteaders who nearly delete their stockpile of summer goodies,

instead relying on the bounty of the winter garden to feed them during

the cold months. Although I'm not ready to give up my freezer of

corn, beans, squash, and tomatoes, I hope that next year's cold season

will bring more fresh food from the garden to our plates.

| This post is part of our Winter Harvest Handbook lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

- Cheap land in an area with cheap land prices. Most people like to think of their home as an investment, but I would have to be in extremely dire straights to sell our beloved farm. Instead of looking for a property that will increase in value, I recommend that folks consider looking for land that they can buy without going into debt and which will maintain a low value so that their property taxes will stay within reasonable bounds. We pay just over $25 per month on property taxes but know people who pay twenty times that much. Do you really want to keep working a mainstream job just to pay property taxes?

- Rural, non-swanky neighborhood.

Although Appalachia has lots of problems, it

also has a slew of

benefits. Around here, building codes are really only an issue in

cities, and even the mayor of a nearby town told Mark that he wouldn't

apply for a building permit for a project like our East Wing.

When I think of all of the hoops we could have had to jump through to

run our seat-of-the-pants operation, I feel very lucky that the long

arm of the law doesn't reach our farm. Our half mile driveway,

passable only by golf carts and four-wheel-drive vehicles, helps us

maintain that independence.

also has a slew of

benefits. Around here, building codes are really only an issue in

cities, and even the mayor of a nearby town told Mark that he wouldn't

apply for a building permit for a project like our East Wing.

When I think of all of the hoops we could have had to jump through to

run our seat-of-the-pants operation, I feel very lucky that the long

arm of the law doesn't reach our farm. Our half mile driveway,

passable only by golf carts and four-wheel-drive vehicles, helps us

maintain that independence.

- Plentiful water. I chose our farm in part because of the huge creek that runs along a boundary and the smaller creek that flows into it, but I didn't realize until we moved here how useful that water really is. Our climate is naturally wet, and many people farm without irrigating, but it's nice to have unlimited water at our beck and call. We also pump that water up into a storage tank to gravity feed to the house for unlimited wash water, which means we can just drink out of our well and not worry about running low on potable water.

Starting with nothing. Although

at first it seems like it would have been easier to step into an

operational farm, in retrospect I'm very glad we started with nothing

except a briar patch. If our farm had come with a pasture,

I suspect we would have immediately bought sheep and a milk cow, and

then we would have had our hands full with serious livestock and

bushhogging weeds while we were still wet behind the ears. Having

to start new garden areas from scratch with hand tools also helped me

rein in my boundless garden dreams to more manageable

proportions. Each year, we add a bit more infrastructure as we

can afford the time and money, and the slow growth gives us time to