archives for 11/2010

"Hey,

Junior, would you mind moving off the road?" Maybe I wasn't being

polite enough, because the calf just stuck out his tongue at me.

"Hey,

Junior, would you mind moving off the road?" Maybe I wasn't being

polite enough, because the calf just stuck out his tongue at me.

I was on my way over to

my movie star neighbor's farm to stream

monitor when I had my bovine encounter. The folks who live in

my neighbor's intentional community spend a lot of their time off the

farm, so they let their neighbor run his beef cattle

on their fields in exchange for working on their driveway. This

calf clearly wasn't used to having anyone in his turf, but he ambled  away

when I inched my car up to his snout.

away

when I inched my car up to his snout.

After freezing our feet

in the Clinch River, we all headed inside to warm up and enthuse over

my neighbor's stunning dwarf

Meyer lemon tree. The lemon has its own alcove (as well as a

patio where it spends its summers) and, as you can see, the tree is

completely laden with fruit. Upstairs, ten baby lemon trees are

growing up while 57 butternuts and a slew of sweet potatoes cure in the

risen warmth.

Later,

we headed down to the garden to see a surprise trio of extremely late

tomatoes. My neighbor stuck the volunteer seedlings in the ground

a month and a half ago and has been covering them with a tarp during

frosty nights. Despite getting a bit nipped on the edges, huge

tomatoes are hanging in the middle of the vines. My neighbor is

bound and determined to pick a ripe tomato on Thanksgiving, and I'm

keen on seeing how his experiment goes.

Later,

we headed down to the garden to see a surprise trio of extremely late

tomatoes. My neighbor stuck the volunteer seedlings in the ground

a month and a half ago and has been covering them with a tarp during

frosty nights. Despite getting a bit nipped on the edges, huge

tomatoes are hanging in the middle of the vines. My neighbor is

bound and determined to pick a ripe tomato on Thanksgiving, and I'm

keen on seeing how his experiment goes.

Back

when every

yard in the Deep South had a hog butchering station, ordinary farmers used to

practice permaculture. They planted persimmons in their pastures

to feed their pigs, cows, and horses, and the smartest farmers

hand-picked persimmon varieties so that they ripened continuously from

August to February. Since no livestock --- even goats and sheep

--- like the leaves, persimmons can be planted directly into pastures

with no protection. Can you imagine seven months of free

livestock feed growing on your hillside?

Back

when every

yard in the Deep South had a hog butchering station, ordinary farmers used to

practice permaculture. They planted persimmons in their pastures

to feed their pigs, cows, and horses, and the smartest farmers

hand-picked persimmon varieties so that they ripened continuously from

August to February. Since no livestock --- even goats and sheep

--- like the leaves, persimmons can be planted directly into pastures

with no protection. Can you imagine seven months of free

livestock feed growing on your hillside?

As always, I'm looking

for plants to include in our chickens'

forest pasture, and

I think persimmons might be a good addition. The downside of

persimmons, in my opinion, is that the fruits are nearly completely

sugar, with only about 3% protein by dry weight. However, my

experience with sugary fruits lying on the ground is that they attract  nearly their own weight in

insects, a chicken's favorite food. Even in the winter, insects

seem to show up if they've got something to eat, and fresh food of any

sort is highly appreciated by my flock during the cold season.

nearly their own weight in

insects, a chicken's favorite food. Even in the winter, insects

seem to show up if they've got something to eat, and fresh food of any

sort is highly appreciated by my flock during the cold season.

This week's lunchtime

series highlights the most interesting and useful facts about

persimmons, drawn out of Tree

Crops: A Permanent Agriculture, by J. Russell Smith, Organic

Orcharding: A Grove of Trees to Live In, by Gene Logsdon, and Two Promising Fruit Plants for Northern

Landscapes,

by E. Goodell (the last of which you can download by clicking on the

link.) It's amazing what delicious reading material turns up when

I take the time to go through my bookcase!

| This post is part of our Persimmons lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The new 18

volt DeWalt portable drill

continues to impress me with its over abundance of power.

I've been trying to estimate

when I hit halfway with the battery time and recharge it at

that point instead of waiting till it drains all the way down. This

might extend the life of each battery. It would help if the next

generation drill had a little indicator light that let you know when

you hit 50 percent.

The

cross-quarter days (rather than solstices and equinoxes) mark the

beginnings of seasons in ancient Irish and east Asian cultures.

Even though these four days --- halfway between the solstice and

equinox --- are primarily pagan holidays, we tend to celebrate them

without knowing it with Groundhog's Day, May Day, and Halloween.

And I've noticed that the cross-quarter days do feel like more

realistic representations of the annual divide than the more mainstream

seasonal holidays of Christmas/Solstice and Easter/Equinox.

The

cross-quarter days (rather than solstices and equinoxes) mark the

beginnings of seasons in ancient Irish and east Asian cultures.

Even though these four days --- halfway between the solstice and

equinox --- are primarily pagan holidays, we tend to celebrate them

without knowing it with Groundhog's Day, May Day, and Halloween.

And I've noticed that the cross-quarter days do feel like more

realistic representations of the annual divide than the more mainstream

seasonal holidays of Christmas/Solstice and Easter/Equinox.

Mark

and I mostly took All Soul's Day off to celebrate the onset of

winter. (As you can see, I couldn't quite resist putting the

first coat of paint on the newly christened East Wing since the

afternoon was so brilliant.) Although a bit of greenery remains

here and there, most of the leaves have fallen and we crossed two big

hurdles this weekend --- the first fire in the wood stove and the first

summer produce thawed out of the freezer. Neither was really

necessary since days are quite warm (once the sun comes up over the

hill around 11 am) and there's still gobs of food in the garden.

But both felt like nice splurges to mark the changing seasons. Happy

Winter!

Mark

and I mostly took All Soul's Day off to celebrate the onset of

winter. (As you can see, I couldn't quite resist putting the

first coat of paint on the newly christened East Wing since the

afternoon was so brilliant.) Although a bit of greenery remains

here and there, most of the leaves have fallen and we crossed two big

hurdles this weekend --- the first fire in the wood stove and the first

summer produce thawed out of the freezer. Neither was really

necessary since days are quite warm (once the sun comes up over the

hill around 11 am) and there's still gobs of food in the garden.

But both felt like nice splurges to mark the changing seasons. Happy

Winter!

Although I'm primarily

interested in growing

persimmons as food for livestock, the persimmon has a long

history as a people food. Here in the United States, Native

Americans added the fruit to their cornbread as sweetener, dried the

pulp for winter fruit, ground seeds into meal, and even made a

beer-like drink by combining persimmons and honey locust pods. In

Asia, persimmons were such a large part of the traditional diet that

farmers cultivated varieties perfect for eating fresh and others just

for drying, then planted them in large orchards. American

cookbooks that are at least a few decades old often include recipes for

persimmon bread and persimmon pudding, the former of which tastes to me

a lot like banana bread.

Although I'm primarily

interested in growing

persimmons as food for livestock, the persimmon has a long

history as a people food. Here in the United States, Native

Americans added the fruit to their cornbread as sweetener, dried the

pulp for winter fruit, ground seeds into meal, and even made a

beer-like drink by combining persimmons and honey locust pods. In

Asia, persimmons were such a large part of the traditional diet that

farmers cultivated varieties perfect for eating fresh and others just

for drying, then planted them in large orchards. American

cookbooks that are at least a few decades old often include recipes for

persimmon bread and persimmon pudding, the former of which tastes to me

a lot like banana bread.

There are dozens of

species of persimmons scattered around the world, but most people

talking about persimmons are interested in just two species. The

persimmon cultivated in Asia (and which you can find in fancy

supermarkets in the U.S.) is primarily Diospyrus

kaki, which has

large fruits that ship well and often competely lack the  puckery astringency that

marks our native persimmon when the fruits aren't quite ripe. A

few people grow the Asian persimmon (sometimes called "kaki", "Japanese

persimmon", or "oriental persimmon") in the United States, but

cultivation is risky north of zone 7, so I'm focusing on our native

species. If you live in the Deep South, the Asian persimmon is

worth looking into since you can find dozens of named varieties, at

least one of which is bound to suit your needs.

puckery astringency that

marks our native persimmon when the fruits aren't quite ripe. A

few people grow the Asian persimmon (sometimes called "kaki", "Japanese

persimmon", or "oriental persimmon") in the United States, but

cultivation is risky north of zone 7, so I'm focusing on our native

species. If you live in the Deep South, the Asian persimmon is

worth looking into since you can find dozens of named varieties, at

least one of which is bound to suit your needs.

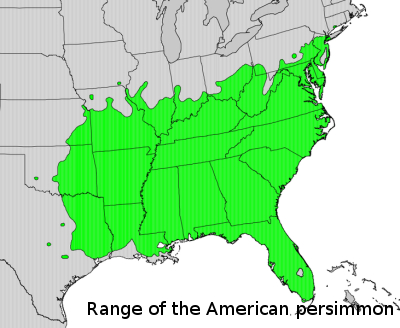

The American persimmon (Diospyrus

virginiana) grows

wild throughout the southeast and is often ignored by locals in modern

times. Little work has been done on breeding tastier varieties

and the fruits have to turn to mush before they are fully ripe, so

they're impossible to ship and will probably never show up at your

local supermarket. On the other hand, the American persimmon is a

more dependable bearer of fruit than the Asian persimmon --- American

persimmons bloom late and are almost never impacted by spring

frosts. According to may people, the American persimmon has a

better taste and is also higher in nutrients like vitamin C and calcium

than the Asian persimmon.

| This post is part of our Persimmons lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It has taken me a long time to wise up to the fact that you usually get

what you pay for when it comes to paint products.

A lesser grade paint may have

needed a 2nd or even a 3rd coat to look good, but this Kilz stuff has what it takes to

cover a wall right the first time.

We got lucky and found a few

cans of this high quality paint discounted where someone had ordered a

mixed color and wasn't quite happy with it.

Recent

visitors to my garden have been drawn to the brilliant yellow-green oilseed radish leaves like moths to a

flame. They skip right past all of my edibles --- lettuce,

broccoli, mustard greens, garlic, potato onions, parsley --- and beg to

eat my cover crops. I don't let them, but I am having a love

affair of my own with the oats, even delaying cutting down the waist-high stand in the

waterlogged back garden because I'm so attached to their beauty.

Recent

visitors to my garden have been drawn to the brilliant yellow-green oilseed radish leaves like moths to a

flame. They skip right past all of my edibles --- lettuce,

broccoli, mustard greens, garlic, potato onions, parsley --- and beg to

eat my cover crops. I don't let them, but I am having a love

affair of my own with the oats, even delaying cutting down the waist-high stand in the

waterlogged back garden because I'm so attached to their beauty.

The

garden is turning into a patchwork quilt of color --- purple swiss

chard, yellow radishes, dark green oats, tan straw. This photo

shows the last corner of the garden that still needs to be put to bed

for the winter. I'll weed the strawberries and mulch them

heavily, then cover up the few bare beds. Due to my extensive

cover crop trials and a moderate fall garden, there are only a handful

of beds that have nothing growing in them. A stroll through the

vibrant garden fends off any winter blues.

The

garden is turning into a patchwork quilt of color --- purple swiss

chard, yellow radishes, dark green oats, tan straw. This photo

shows the last corner of the garden that still needs to be put to bed

for the winter. I'll weed the strawberries and mulch them

heavily, then cover up the few bare beds. Due to my extensive

cover crop trials and a moderate fall garden, there are only a handful

of beds that have nothing growing in them. A stroll through the

vibrant garden fends off any winter blues.

Both American

and Asian persimmons can be tricky to grow, which in part explains

their absence from many permaculturalists' gardens. Although you

can buy named persimmon varieties from nurseries, you're taking a big

chance since persimmons put down a long taproot and hate to be

transplanted. In addition, Gene Logsdon reports that persimmon

seeds germinate better and trees transplant better into forest soil

rather than into garden soil, suggesting to me that there may be some

kind of soil microorganism the tree needs to associate with in order to

grow well. From

all I've read, your best bet for growing persimmons is to mimick

natural conditions, gathering wild seeds and planting them into a wild

habitat.

Both American

and Asian persimmons can be tricky to grow, which in part explains

their absence from many permaculturalists' gardens. Although you

can buy named persimmon varieties from nurseries, you're taking a big

chance since persimmons put down a long taproot and hate to be

transplanted. In addition, Gene Logsdon reports that persimmon

seeds germinate better and trees transplant better into forest soil

rather than into garden soil, suggesting to me that there may be some

kind of soil microorganism the tree needs to associate with in order to

grow well. From

all I've read, your best bet for growing persimmons is to mimick

natural conditions, gathering wild seeds and planting them into a wild

habitat.

In tomorrow's post, I'll

run through all of the tricks I've read about for getting your

persimmons to sprout and grow, but there are a few other things to

consider as you plan your planting. On the positive side, once

that seedling sprouts or that transplant puts down new roots,

persimmons can live quite well in poor soil, seeming to thrive in just

about every soil type out there. The trees will grow in the shade

(although they need sun to fruit), so you can get away with starting

them in a small gap in existing forest, opening up the canopy bit by

bit as your persimmon tree grows.

Keep in mind that

persimmons are large trees, requiring at least 30 feet spacing, and

that most trees are either male or female. Although you might get

lucky and find a variety that is self-pollinating (like the one in the

photo to the left), in general you should plan to plant at least one

male for every twelve female persimmons.

Finally, be aware that

there are two races of American persimmons and that the races can't

interbreed. The tetraploid race, with 60 chromosomes, is found in

the

southern Appalachians while the hexaploid race, with 90 chromosomes,

grows further north and west. In general, the latter has larger

fruits

that ripen earlier and has wider, more fuzzy leaves. If you're

going to try to start an orchard from seed, you may want to include

both races to extend your harvest, in which case you'll need to be sure

to plant both a tetraploid and a hexaploid male to pollinate your

females.

As a final side note,

persimmon flowers are reportedly beloved by bees. Maybe that will

push a few beekeepers over the edge into including persimmons in their forest pastures.

| This post is part of our Persimmons lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The tree we identified lately

as having wild

oyster mushrooms growing

out of it decided to fall in our driveway, which felt to me like it was

screaming "Cut me up....take me home...and Eat Me!"

I guess I'm always happy to

oblige a talking mushroom tree when it offers up such a yummy gift.

Everett posted over on Living

A Simple Life about the things

he wishes he could do (or at least do better.) He tagged me and Mark

to share our own lists of dream skills, and I got quite inspired by the

project. I'm a student at heart, and there's nothing I love more

than setting up my own lesson plans. So, here's my current course

of study:

Everett posted over on Living

A Simple Life about the things

he wishes he could do (or at least do better.) He tagged me and Mark

to share our own lists of dream skills, and I got quite inspired by the

project. I'm a student at heart, and there's nothing I love more

than setting up my own lesson plans. So, here's my current course

of study:

- Learn all of the skills necessary to create a permaculture system that feeds us with few non-waste inputs from outside the farm. This set of skills is what the Walden Effect is all about, and includes lots of things I'm currently learning: propagating mushrooms, figuring out forest pastures, growing our own straw, pressing our own oil, and much more.

Learning to live in the moment.

Mark has helped me make enough progress on this step that I can see how

amazing it would be to be able to fully relax and self-indulge, to let

go of time completely and simply be

from time to time. I've got a lot more to learn, though.

Learning to live in the moment.

Mark has helped me make enough progress on this step that I can see how

amazing it would be to be able to fully relax and self-indulge, to let

go of time completely and simply be

from time to time. I've got a lot more to learn, though.- Becoming fluent in Spanish. Ever since my family took me on a field trip to New York City and I heard some kids chattering away in Spanish on the subway, I've dreamed of being fully functional in another language. Despite four years of high school Spanish, though, I barely made any progress until I began studying the Platiquemos system on my own this year. Finally, I think I might be able to speak Spanish at the level of a two year old! Clearly, I have a ways to go.

Learning to create community. My

weakest point is my extreme introversion which makes it tough to make

new friends or hang out with strangers. But I dream of tempting

some of our blog readers and other like-minded folks to settle here in

our county where we can bandy ideas back and forth a little better than

we do over the internet. I'm not sure exactly what skills I would

need to make this happen, but it's a dream, so it goes on the list.

Learning to create community. My

weakest point is my extreme introversion which makes it tough to make

new friends or hang out with strangers. But I dream of tempting

some of our blog readers and other like-minded folks to settle here in

our county where we can bandy ideas back and forth a little better than

we do over the internet. I'm not sure exactly what skills I would

need to make this happen, but it's a dream, so it goes on the list.- Learning to write fiction in a way that doesn't make me cringe. Non-fiction is easy for me to write, but I've always been drawn to a challenge, so I dream of one day writing a fiction piece that I can look at the next day without blushing.

Everett's list is 19

items long, so I feel a bit silly stopping at five, but I did include

about a dozen in the permaculture goal. I've never had a shortage

of skills I want to learn, so I'm sure that in a decade when I've

figured all of this out, I will have another five or ten items to teach

myself. What skills do you dream of perfecting?

If you haven't already,

please read my previous post to learn about persimmon

spacing, varieties, and other factors to consider when planning your

persimmon orchard.

This post is a quick rundown on three methods of persimmon propagation.

If you haven't already,

please read my previous post to learn about persimmon

spacing, varieties, and other factors to consider when planning your

persimmon orchard.

This post is a quick rundown on three methods of persimmon propagation.

Starting

persimmons from seed.

The cheapest (and probably least problematic) method of growing

persimmons is to gather seeds from wild trees and sprout them right

where you want your own persimmon to grow. I've had mixed success

with sprouting persimmon seeds, but I now know that if you use a couple

of tricks, your persimmons will germinate quite well. First,

gather whole persimmon fruits and remove the seeds, but don't let

the seeds dry out.

Your seeds will need to stratify,

so plant them in fall or winter, no more than an inch deep in the

soil. Persimmon seeds won't germinate until late spring, so if

you want to be able to keep track of them, you might try planting your

seeds in outdoor pots at this time of year, then transplanting them

into their final location as soon as they germinate and before they

send down their long tap root. If you choose the pot method,

plant your seeds in soil taken from the woods to promote germination.

As I cleaned my first batch

of persimmon seeds, I noticed that a layer of pulp continued to cling

to the seed, so I'm experimenting with whether persimmon seeds also

need a fermentation stage. I planted half of my seeds

directly into pots of woodland soil, and am letting the other seeds

soak in water for a week or two the way I do with tomato

seeds. I'll

report back this spring about which method gave me better germination

rates.

As I cleaned my first batch

of persimmon seeds, I noticed that a layer of pulp continued to cling

to the seed, so I'm experimenting with whether persimmon seeds also

need a fermentation stage. I planted half of my seeds

directly into pots of woodland soil, and am letting the other seeds

soak in water for a week or two the way I do with tomato

seeds. I'll

report back this spring about which method gave me better germination

rates.

Grafting

persimmons.

Starting persimmons from seed is relatively easy, but your final tree

may or or may not be exactly the way you want it to be. You can

develop your own, locally adapted persimmon varieties by setting aside

a patch of land to test out dozens of different seeds. The

persimmons in your test strip can be planted much closer together since

you just need them to grow to about five feet tall, at which point they

will begin to fruit. Select your favorite varieties from this

test bed (maybe an early, mid-season, and late tree?) and graft scion

wood onto seedlings started at the same time in their permanent

location. I won't go into the basics of grafting here, but I've

read that persimmons can be grafted using the same methods you would

use to graft apples.

Transplanting persimmons.

If at all possible, it's best to plan your persimmon orchard so that

you don't need to transplant. However, if for some reason it's

essential to move a persimmon from one spot to another, orchardists

have developed a method that is time-consuming but which seems to work.

Transplanting persimmons.

If at all possible, it's best to plan your persimmon orchard so that

you don't need to transplant. However, if for some reason it's

essential to move a persimmon from one spot to another, orchardists

have developed a method that is time-consuming but which seems to work.

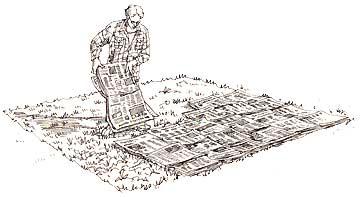

The best time to

transplant is at the beginning of the third growing

season. To prepare, prune the roots the previous summer by

digging your spade into the soil a few inches from the trunk of the

tree in alternating sections, as is shown in the image to the

right. Two months later, repeat the process, cutting into the

areas that were left uncut last time. This process will make your

persimmon grow roots close to the trunk where you'll be able to dig

them up (although you'll still lose the taproot.)

During the next dormant

season, lay out black plastic in the area you

plan to transplant into. This will warm the soil up so that when

you transplant the persimmon in early spring, it is ready to grow

immediately. Prune back the top of the tree extensively so that

only half to a third of the branches remain, then transplant the

persimmon into its new location. Keep the persimmon very well

waterered until mid summer --- a flush of growth right off the bat

doesn't mean that your tree is established and can be ignored. If

your persimmon is still alive, stop watering in August to let it harden

off for the winter.

After reading all of

that, you probably think, like I do, that it's

best to just start seedlings! I'm currently gathering seeds from

persimmons that ripen at various times, with the goal of putting some

directly into the forest pasture in the spring and others into a test

strip for later grafting onto male seedlings in the pasture. Like

many parts of my forest pasture

experiment, growing persimmons is a

long term project, with seedlings slated to bloom in four to eight

years and then the grafted persimmons not beginning to fruit until

three years after that. Maybe by 2020, persimmons will make up a

significant portion of our chickens' diets.

| This post is part of our Persimmons lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I've always heard chickens

like to roost at night off the ground and on some sort of stick.

Well for whatever reason our

chickens don't seem to like the roost I made for them in the coop. They prefer hunkering down on the ground in the weeds instead.

The above stump has been a

popular place at night, which is why I thought a roost extention might

just be the thing to remind them how nice it is to sleep off the ground.

Regular

readers may remember that we're creating

a forest garden in a patch of young woods, leaving some useful trees

but replacing others with cultivated species that do well in partial

shade when young --- mostly nuts. Since nut trees grow so big,

there's really only room for three or four trees on the little table of

flat forestland, and last year I thought I'd filled it up with a

butternut, a persimmon, and a Chinese chestnut. Now I know that persimmons

hate to be transplanted, so it's no surprise that my

Regular

readers may remember that we're creating

a forest garden in a patch of young woods, leaving some useful trees

but replacing others with cultivated species that do well in partial

shade when young --- mostly nuts. Since nut trees grow so big,

there's really only room for three or four trees on the little table of

flat forestland, and last year I thought I'd filled it up with a

butternut, a persimmon, and a Chinese chestnut. Now I know that persimmons

hate to be transplanted, so it's no surprise that my

transplanted persimmon kicked the bucket. I didn't mark the

chestnut, and thought it had died too (although, as you'll see later,

it didn't.) Having read that Carpathian

walnuts are a more cold hardy version of the English walnut, I decided to buy a pair and

fill in the gaps.

transplanted persimmon kicked the bucket. I didn't mark the

chestnut, and thought it had died too (although, as you'll see later,

it didn't.) Having read that Carpathian

walnuts are a more cold hardy version of the English walnut, I decided to buy a pair and

fill in the gaps.

The nut orchard is too

far from our usual stomping grounds to have running water or golf cart

access, so trees planted there suffer from neglect and I decided to see

if a better planting job might help our new walnuts survive without

supplemental watering. I planted each tree in a small depression

and mounded up dirt on the downhill side to catch rainwater, then I

raked up leaves from under nearby trees to mulch each walnut

heavily. Since I'm fall planting, the trees should have time to

establish a good root structure before they're faced with any potential

summer droughts.

When

placing my second walnut, I wandered around the woods until I found the

spot with the best canopy gap, then proceeded to dig my hole, ripping

up small trees in the surrounding area. My hands plucked out the

Chinese chestnut I'd carefully planted in the exact same spot last year

just as my brain was saying "No! Wait! That's a good

tree!" I have no clue if the seedling will survive the abuse, but

I gave it a new home thirty feet further down the the plateau, and I

really do plan to mark it...the next time I'm up that way.

up small trees in the surrounding area. My hands plucked out the

Chinese chestnut I'd carefully planted in the exact same spot last year

just as my brain was saying "No! Wait! That's a good

tree!" I have no clue if the seedling will survive the abuse, but

I gave it a new home thirty feet further down the the plateau, and I

really do plan to mark it...the next time I'm up that way.

The tannins in unripe

persimmons are thoroughly unpleasant, so it's no wonder that folklore

has arisen to teach us how to ripen the fruits. Every real

Appalachian knows that frost ripens persimmons, and some of us even go

so far as to simulate the frost. I once put a bag of persimmons

in the freezer then pulled them out a week later, hoping they would be

sweet and ripe. When I went over to visit my movie star neighbor

last week, I saw that he had laid his persimmons outside in a platter

so that a hard freeze would ripen them up. Too bad we were both

on the wrong track.

The tannins in unripe

persimmons are thoroughly unpleasant, so it's no wonder that folklore

has arisen to teach us how to ripen the fruits. Every real

Appalachian knows that frost ripens persimmons, and some of us even go

so far as to simulate the frost. I once put a bag of persimmons

in the freezer then pulled them out a week later, hoping they would be

sweet and ripe. When I went over to visit my movie star neighbor

last week, I saw that he had laid his persimmons outside in a platter

so that a hard freeze would ripen them up. Too bad we were both

on the wrong track.

Scientists have discovered

that persimmons ripen like most other fruits, and that frost near the

time of ripening is purely coincidental. That said, you can

hasten the ripening of your fruits by putting persimmons in a plastic

bag with an apple. The ethylene released by the apple will make

your persimmon ripen up as long as the persimmon fruit has already

become somewhat soft on the tree.

What do you do if you bite

into a persimmon and the puckery astringency makes you spit it right

back out? I tested a few puckery persimmons on our flock, and our

chickens gave persimmons two thumbs up. In fact, the persimmons

started a soccer match --- the most intense one I've seen among our

flock yet. Clearly, chickens think persimmons are delicious,

tannins or no tannins.

What do you do if you bite

into a persimmon and the puckery astringency makes you spit it right

back out? I tested a few puckery persimmons on our flock, and our

chickens gave persimmons two thumbs up. In fact, the persimmons

started a soccer match --- the most intense one I've seen among our

flock yet. Clearly, chickens think persimmons are delicious,

tannins or no tannins.

| This post is part of our Persimmons lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

1. How to make my own music.

1. How to make my own music.

2. How to tell a story

with animation.

3. How to make our own

electricity.

4. How to be more in

touch with nature.

5. How to fly a

powered parachute cross country.

6. How to grow more of

our own food.

7. How to meet people

as weird as myself.

8. How to sail a boat

to Mexico.

I would also like to know who

really shot JFK, what really happened on September 11th 2001, and why Huckleberry never seems to be satisfied.

Image credit goes to coverbrowser.com

for sharing the secret of perpetual motion.

Our Chicago Hardy Fig arrived

on the same day as our Carpathian walnuts even though it was coming

from a different nursery --- clearly, this must be prime fall-planting

time in zone 6. Like rosemary, planting figs outdoors is a

dicey proposition in our region, but I'm hopeful that careful variety

selection and winter protection will let us harvest our own fruits in a

few years.

Our Chicago Hardy Fig arrived

on the same day as our Carpathian walnuts even though it was coming

from a different nursery --- clearly, this must be prime fall-planting

time in zone 6. Like rosemary, planting figs outdoors is a

dicey proposition in our region, but I'm hopeful that careful variety

selection and winter protection will let us harvest our own fruits in a

few years.

If various fig-growers

on the internet are to be believed, the hardiest fig varieties are

Chicago Hardy, Mission, Brown Turkey, Alma, Nordland, and

Celeste. Chicago Hardy won my admiration since it's reputed to be

able to produce fruit on new wood even if the top dies back to the

ground, which means that as long as the roots don't die, we will get

some sort of crop from our fig every year. In contrast, if you're

growing another variety of fig, you will have to wait until the next

year (and risk being winter-killed again) before tasting fruits from

your fig after a cold winter.

Despite the promise of cold

hardiness, I went ahead and protected my fig, staking a loop of trellis

fencing around it and then filling the loop up with leaves. In

coldier climates (zone 5), fig growers go to more extremes, sometimes

carefully bending the plant over and burying it in a trench of

soil. Other growers simply convert their fig to a potted plant

and bring it in for the winter.

Despite the promise of cold

hardiness, I went ahead and protected my fig, staking a loop of trellis

fencing around it and then filling the loop up with leaves. In

coldier climates (zone 5), fig growers go to more extremes, sometimes

carefully bending the plant over and burying it in a trench of

soil. Other growers simply convert their fig to a potted plant

and bring it in for the winter.

As a final note, growers

of Chicago Hardy do have one warning I plan to take to heart.

This particular variety of fig fruits much less if unpruned, so be sure

to cut stems back to 30 inches every year and clear out all but three

main branches. If all goes as planned, we could be tasting our

first homegrown fig as early as 2012.

If you're looking for a wide

variety of heirloom apple trees grafted and tended by a master, the Urban Homestead in Bristol, Virginia, is the

place for you. I could spend hours poring over the descriptions of

their old-fashioned apple varieties, of which this excerpt is a prime

example:

If you're looking for a wide

variety of heirloom apple trees grafted and tended by a master, the Urban Homestead in Bristol, Virginia, is the

place for you. I could spend hours poring over the descriptions of

their old-fashioned apple varieties, of which this excerpt is a prime

example:

Ben

Davis - The most

widely planted apple variety in the South after the Civil

War. Think of it as the

nineteenth century’s Red Delicious. A

large, dull-red apple; hardy, vigorous,  dependable, productive.

Keeps like a cobblestone. Often

described as having only passing flavor. Ms.

Genevieve Gray, an octogenarian from South Elgin, Illinois sent us a

story

several years ago that well illustrates the point:

“There was a joke going around when I was a girl about a fellow who

claimed to be such an expert in recognizing apples by taste that he

could

identify any kind blindfolded. He

was challenged, of course, and given apple after apple to

taste--identifying

each correctly. Finally, in

desperation to fool him, one of the challengers grabbed a large piece

of cork,

carved it into the shape of an apple, and offered it to him.

He bit out a chunk, hesitated, bit out another, then reluctantly

admitted

that he wasn’t real sure. “I

think it’s a Ben Davis,” he said. And

then he quickly added, “But if it is, it’s the best one I’ve ever

eaten.” We would add only that

any tree that can stand up to 125 years of ribbing

dependable, productive.

Keeps like a cobblestone. Often

described as having only passing flavor. Ms.

Genevieve Gray, an octogenarian from South Elgin, Illinois sent us a

story

several years ago that well illustrates the point:

“There was a joke going around when I was a girl about a fellow who

claimed to be such an expert in recognizing apples by taste that he

could

identify any kind blindfolded. He

was challenged, of course, and given apple after apple to

taste--identifying

each correctly. Finally, in

desperation to fool him, one of the challengers grabbed a large piece

of cork,

carved it into the shape of an apple, and offered it to him.

He bit out a chunk, hesitated, bit out another, then reluctantly

admitted

that he wasn’t real sure. “I

think it’s a Ben Davis,” he said. And

then he quickly added, “But if it is, it’s the best one I’ve ever

eaten.” We would add only that

any tree that can stand up to 125 years of ribbing  has

earned its place in the

orchard.

has

earned its place in the

orchard.

The Urban Homestead

offers just shy of 100 old and new favorites, and yet they feel obliged

to add this apologetic note to the website: "Economics dictates that we keep a tight rein on the

number of varieties

we graft each season. We have

access, however, to a large number of stock trees, and offer a custom

grafting

service for some of the harder-to-find varieties." Basically, if you've

heard of it, they can probably get it for you. I was thrilled to

read that they have not just one, but two versions of the old-fashoned

Winesap (as well as the easier to find Stayman Winesap.) I

ordered a Winesap and Liberty from them to round out our orchard.

Tim Hensley is the man behind

this 2 acre operation, which he fits into his suburban backyard and a

rented lot across the street. I was charmed to see three of his

sons digging and labeling apple trees while I snooped around the

premises, and their father said that all of his kids help out ---

except for the four year old, who isn't terribly handy yet. I'm

going to have to reserve tomorrow's post for notes on his intriguing

permaculture techniques, but suffice it to say that he's not an

old-fashioned apple grower even if his apples have deep roots.

Tim Hensley is the man behind

this 2 acre operation, which he fits into his suburban backyard and a

rented lot across the street. I was charmed to see three of his

sons digging and labeling apple trees while I snooped around the

premises, and their father said that all of his kids help out ---

except for the four year old, who isn't terribly handy yet. I'm

going to have to reserve tomorrow's post for notes on his intriguing

permaculture techniques, but suffice it to say that he's not an

old-fashioned apple grower even if his apples have deep roots.

In addition to apples

($18 to $28, depending on size of tree), Tim Hensley also sells a

selection of other edible plants, not all of which are listed on his

website. For example, I was shocked to see rows of Chicago

Hardy figs, just

like the one I mail-ordered --- I wish I'd realized I could pick them

up in person at the Urban Homestead!

Speaking

of picking them up, if you live closeby, I highly recommend that you

make the drive to the Urban Homestead, not only to get your trees in

the ground ASAP so that they will thrive, but also to explore Hensley's

operation. Mom wants you to know that they have the best swing

she's enjoyed in years. On the other hand, don't let distance

stop you --- Tim Hensley mails his trees across the United States.

Speaking

of picking them up, if you live closeby, I highly recommend that you

make the drive to the Urban Homestead, not only to get your trees in

the ground ASAP so that they will thrive, but also to explore Hensley's

operation. Mom wants you to know that they have the best swing

she's enjoyed in years. On the other hand, don't let distance

stop you --- Tim Hensley mails his trees across the United States.

The Urban Homestead is

located on 818 Cumberland St., behind the library in Bristol.

Give them a call at (276) 466-2931 or an email at urbanhomestead@aol.com. Don't forget that

buying heirloom apples not only preserves a vanishing tradition but

also means your trees are more likely to survive the pests that nature

throws at them with no need for posionous sprays.

The Urban Homestead is

located on 818 Cumberland St., behind the library in Bristol.

Give them a call at (276) 466-2931 or an email at urbanhomestead@aol.com. Don't forget that

buying heirloom apples not only preserves a vanishing tradition but

also means your trees are more likely to survive the pests that nature

throws at them with no need for posionous sprays.

We've had the Chopper1 in service for one complete

firewood chopping season and I'm ready to declare it my all time

favorite axe.

What I like most about this

invention is the fact that it never gets stuck in a wedged sort of way

that the old Super

Splitter was prone to do.

Not only did it take more energy to separate the maul from the wood but

it breaks up your pace.

Sometimes the Chopper1 will

bounce off a log, but that's only when I haven't applied enough force

in my swing.

Even

though he had customers to the Urban

Homestead showing up

right and left, Tim Hensley was kind enough to take a few minutes out

of his Saturday afternoon to give me a quick tour of his

backyard. There, I learned answers to three pressing questions

that I've been pondering for a while.

Even

though he had customers to the Urban

Homestead showing up

right and left, Tim Hensley was kind enough to take a few minutes out

of his Saturday afternoon to give me a quick tour of his

backyard. There, I learned answers to three pressing questions

that I've been pondering for a while.

How

do you keep enough adult apple trees on hand to provide scionwood for

100 heirloom varieties in a tiny city lot? Tim espaliers many of his apple trees so

that they can fit in a small space, then he adds a permaculture twist,

running his chickens under the espaliered trees to prevent populations

of bad bugs from building up. In addition to planting these

espaliered trees just a couple of feet apart, he has a few rows of

adult trees in his nursery planted five or six feet apart.

Clearly, close spacing is okay if you're growing the trees for

scionwood (or, presumably, as a test orchard.)

I've read that the triofliate

orange is a species of citrus that is hardy enough to fruit in zone 6,

but I've heard varying reports on its flavor. What do you think? Tim Hensley just

happened to have a Flying Dragon trifoliate orange on the side of his

house. It was loaded with lovely fruits, and I could tell the

mass of thorns would make good hedge material. However, Tim was

less impressed by the flavor. Trifoliate oranges are really only

good enough for making lemonade or marmalade, and Tim said that the

resulting food had a "plasticky" flavor. I guess I'll stop

considering planting a trifoliate orange.

I've read that the triofliate

orange is a species of citrus that is hardy enough to fruit in zone 6,

but I've heard varying reports on its flavor. What do you think? Tim Hensley just

happened to have a Flying Dragon trifoliate orange on the side of his

house. It was loaded with lovely fruits, and I could tell the

mass of thorns would make good hedge material. However, Tim was

less impressed by the flavor. Trifoliate oranges are really only

good enough for making lemonade or marmalade, and Tim said that the

resulting food had a "plasticky" flavor. I guess I'll stop

considering planting a trifoliate orange.

Will

my hardy figs survive the winter and fruit? Tim has two huge and

lovely fig trees growing in his yard. The first --- LSU Purple

--- has never fruited for him and he doesn't recommend it in our

climate. On the other hand, he told me that his Chicago

Hardy fig has never been winter-killed, perhaps because it is

tucked into a beautiful nook surrounded on two sides by his house and

with the dryer exhaust vent coming out nearby. I feel like he

told me he wasn't getting many fruits off of the Chicago Hardy, but all

of the information I was trying to take in is starting to get mushed up

in my head. Maybe Mom can chime in with her memory here....

Finally,

I enjoyed trading broiler tales with Tim and one of his customers, Brody

from Damascus. Brody told us that he likes to soak his newly

killed chickens in a bath of icy saltwater, which he said hastens the

end of rigor mortis so that he can freeze his chickens nearly right

away and still get tender meat. I'd be curious to hear if anyone

else has had any experience with the saltwater trick.

Finally,

I enjoyed trading broiler tales with Tim and one of his customers, Brody

from Damascus. Brody told us that he likes to soak his newly

killed chickens in a bath of icy saltwater, which he said hastens the

end of rigor mortis so that he can freeze his chickens nearly right

away and still get tender meat. I'd be curious to hear if anyone

else has had any experience with the saltwater trick.

We were thrilled when Mark's

mom gave us an external wood

furnace

a couple of years ago, and we are still very grateful. However,

over time, we've discovered that external wood furnaces have a variety

of problems associated with them:

We were thrilled when Mark's

mom gave us an external wood

furnace

a couple of years ago, and we are still very grateful. However,

over time, we've discovered that external wood furnaces have a variety

of problems associated with them:

- Extremely inefficient. Even the most efficient new wood furnance I could find in my web searches (the Mini-Caddy, listed as an Energy Star furnace, and pictured here) is vastly inferior to moderately efficient wood stoves. You can download a list of EPA certified wood stoves which will tell you the emissions and efficiency of all tested models. The Caddy, which the Mini-Caddy is based on, has 6.6 g/hr emissions and 63% efficiency. Compare it, for example, to the Drolet Savannah wood stove (which has slightly less output than the Mini-Caddy and is much cheaper) --- 6.28 g/hr emissions and 75% efficiency.

- Expensive. We got very lucky and were given our furnace as a gift, so I wasn't prepared for the price tag when we considered upgrading to a more efficient model. The Mini-Caddy seems to retail for somewhere in the $2,000 range, compared to efficient, non-catalytic wood stoves that can be got for closer to $700 (and which also have higher efficiency, don't forget.) You can get a 30% federal tax credit on either purchase.

Not suited

for indoor use. After finishing up the East Wing, we moved

in our wood furnace, figuring that we'd be able to capture some of the

heat previously lost to the outside air. I know that the term "exterior

wood furnace" should have tipped me off, but we were shocked at how

smoky the East Wing got when we lit our first fire this year.

Granted, our model (LTD Limited by Jordahl Mfg.) is very old, and its

drawing problem may not be

found in more modern wood furnaces.

Not suited

for indoor use. After finishing up the East Wing, we moved

in our wood furnace, figuring that we'd be able to capture some of the

heat previously lost to the outside air. I know that the term "exterior

wood furnace" should have tipped me off, but we were shocked at how

smoky the East Wing got when we lit our first fire this year.

Granted, our model (LTD Limited by Jordahl Mfg.) is very old, and its

drawing problem may not be

found in more modern wood furnaces.

- Fails during power outages.

Without

electricity to turn on the electric fan, we had to burn huge fires in

our furnace to keep the trailer at all habitable during last year's 10

day power outage.

Is meant to

heat the whole house rather than a small section. You have

to burn a lot more wood in general to keep your house warm using an

exterior furnace since you depend on fans to move the hot air

throughout the house. With an indoor wood stove, you can situate

the stove in the population center of the house and burn small fires to

heat just that area.

Is meant to

heat the whole house rather than a small section. You have

to burn a lot more wood in general to keep your house warm using an

exterior furnace since you depend on fans to move the hot air

throughout the house. With an indoor wood stove, you can situate

the stove in the population center of the house and burn small fires to

heat just that area.

All told, our exterior

wood furnace has definitely been better than

heating with electric space heaters, but we run through wood like

nobody's business. This week, I'm going to post about some of the

options we're considering --- I suspect you'll all have good advice, so

please chime in!

| This post is part of our Wood Stove lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Edited to add:

Learn how to safely install an energy-efficient wood stove in a moibile

home in Trailersteading. Now available for

$1.99 on Amazon.

The project to bury our

waterline is now at the point where the pipe comes out of the tank.

My plan is to build a small,

insulated enclosure that follows the pipe out of the tank for 5 or 6

feet before it begins to be submerged.

Stay tuned to see if this

experiment prevents pipe freezing like I think it might.

I

was a bit concerned by the bee hive that dropped 540 varroa mites in

three days when I tested

in the middle of September, so I decided to do a

re-test and see what the mite populations are like in early

November. This time, all I had on hand were some four inch wide

strips of cardboard that are a byproduct of the way we package our pre-made

chicken waterers, so

I went ahead and lathered those with petroleum jelly and stuck them

under the screened bottom boards of our hives.

I

was a bit concerned by the bee hive that dropped 540 varroa mites in

three days when I tested

in the middle of September, so I decided to do a

re-test and see what the mite populations are like in early

November. This time, all I had on hand were some four inch wide

strips of cardboard that are a byproduct of the way we package our pre-made

chicken waterers, so

I went ahead and lathered those with petroleum jelly and stuck them

under the screened bottom boards of our hives.

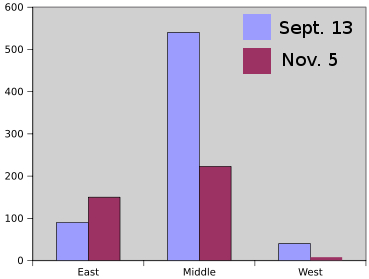

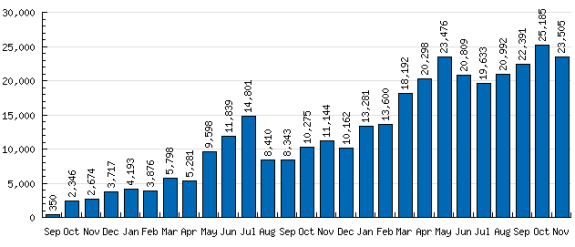

Three

days later, I counted mites and did a bit of math to determine what the

total mite fall would have been if I had put something under the entire

bottom board. As you can see from this graph, the hive with all

of the varroa mites in September dropped down to a far more manageable

level (223 mites) in November. None of the other hives have mite

populations in the danger zone at all.

Three

days later, I counted mites and did a bit of math to determine what the

total mite fall would have been if I had put something under the entire

bottom board. As you can see from this graph, the hive with all

of the varroa mites in September dropped down to a far more manageable

level (223 mites) in November. None of the other hives have mite

populations in the danger zone at all.

Most sources report that

mite numbers rise as autumn progresses, so I'm not quite sure why I saw

declining varroa mite numbers. I assume that as workers die and

aren't replaced, the hive hosts fewer varroa mites as well.

Regardless of the reason for low mite populations in my hives, I'm

happy to be heading into the winter without chemical pesticides in the

hive.

We

started out with an exterior wood

furnace because we had been told by

reputable sources that you can't put a wood stove in a mobile

home. It turns out that's just not true. Instead, there are

a series of guidelines to follow when installing a wood stove in a

trailer, and you also need to choose a wood stove specially tested to

be

mobile home safe.

We

started out with an exterior wood

furnace because we had been told by

reputable sources that you can't put a wood stove in a mobile

home. It turns out that's just not true. Instead, there are

a series of guidelines to follow when installing a wood stove in a

trailer, and you also need to choose a wood stove specially tested to

be

mobile home safe.

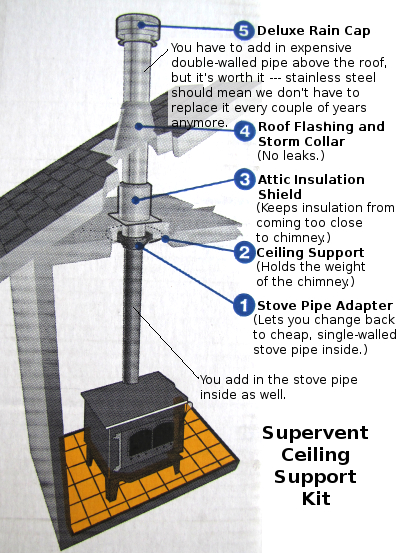

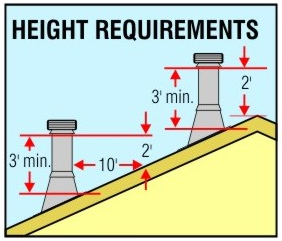

This

Mother Earth News article (from which I snagged the

diagram in this post) and this more up to

date site

together tell you everything you need to know about installing a wood

stove in a mobile home. The differences between mobile home and

traditional home installation come down to six main points:

- A close clearance pipe must be used to connect the stove to the chimney.

- Spark arresters are installed in the chimney cap.

- The stove should be grounded to the home chassis.

- The stove must have tie downs to attach it to the floor so it won't shift around when the trailer is moved. (Presumably, this is only relevant if your trailer is less than forty years old and will actually be moved again.)

- The stove should use exterior air for combustion.

- Wood stoves are not permissable in mobile home bedrooms.

In

addition, you should choose a wood stove that has been approved for use

in a mobile home. In general, these stoves are on the small to

medium side and have a top-exiting flue collar and a heat shield on the

back. These characteristics combine to make the clearance around

all sides of the stove less, which in turn lets them fit into a mobile

home. In fact, from browsing the internet, it sounds like the

small size of mobile homes is really the biggest danger feature, so

your goal should be to find a spot for your wood stove where you can

provide plenty of air space around it.

In

addition, you should choose a wood stove that has been approved for use

in a mobile home. In general, these stoves are on the small to

medium side and have a top-exiting flue collar and a heat shield on the

back. These characteristics combine to make the clearance around

all sides of the stove less, which in turn lets them fit into a mobile

home. In fact, from browsing the internet, it sounds like the

small size of mobile homes is really the biggest danger feature, so

your goal should be to find a spot for your wood stove where you can

provide plenty of air space around it.

The cheapest mobile home

compatable wood stoves that I've found are the

Drolet Savannah 55,000 BTU stove (83% efficient!) and the Century

Heating 50,000 BTU stove for $700 and $650, respectively, from Northern

Tool and Equipment. For our tiny trailer, even these would be

overkill, so I was glad to hear that many other models can be converted

to mobile home wood stoves by adding on an outside air kit (around $50

to $60.)

| This post is part of our Wood Stove lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Edited to add:

Learn how to safely install an energy-efficient wood stove in a moibile

home in Trailersteading. Now available for

$1.99 on Amazon.

I ended up using the standard

foam pipe cover and then added a couple wraps of Reflectix for the new water

tank anti-freeze box.

Now we wait for the next

freeze to see how well this protection holds up.

For

the last few years, our first frost of the year was a killing frost,

but this year we got a bit of a reprieve. Even though our

first frost came right on schedule in the middle of October, we didn't have a killing

frost until November 6.

For

the last few years, our first frost of the year was a killing frost,

but this year we got a bit of a reprieve. Even though our

first frost came right on schedule in the middle of October, we didn't have a killing

frost until November 6.

In case you're

scratching your head in puzzlement, a killing frost is generally

considered to be a frost with temperatures at or below 25 degrees

Fahrenheit. Lighter frosts will kill your summer-loving plants

like tomatoes and okra, but fall crops shrug these baby frosts off and

keep right on growing. A killing frost, though, tends to take out

all but the  most

hardy garden plants --- the few uncovered lettuce plants were mildly

nipped by our recent frost and the broccoli was slightly damaged, but

mustard and kale were still green and happy the next morning.

most

hardy garden plants --- the few uncovered lettuce plants were mildly

nipped by our recent frost and the broccoli was slightly damaged, but

mustard and kale were still green and happy the next morning.

The first killing frost

also tends to knock the last of the autumn color out of the trees, so

now only a few oak leaves cling to the branches. Our hills

suddenly seem much lower when you can see through the trees.

Our homemade chicken waterer is always POOP-free.

I've

recently come to the conclusion that there are two ways of being green

--- the Prius method and the penny-pinching method. Followers of

the Prius method spend a lot of money to buy the most expensive model,

not realizing that the increased efficiency they're paying for could be

obtained just as easily (and much more cheaply) by downsizing a

bit. For example, my 20+ year old Ford Festiva has gas mileage

nearly compatible with the Prius for a fraction of the up-front cost

(and a fraction of the construction cost since my Festiva has already

been on

the road for two decades.)

I've

recently come to the conclusion that there are two ways of being green

--- the Prius method and the penny-pinching method. Followers of

the Prius method spend a lot of money to buy the most expensive model,

not realizing that the increased efficiency they're paying for could be

obtained just as easily (and much more cheaply) by downsizing a

bit. For example, my 20+ year old Ford Festiva has gas mileage

nearly compatible with the Prius for a fraction of the up-front cost

(and a fraction of the construction cost since my Festiva has already

been on

the road for two decades.)

Which is all a way

of saying that there are two ways to buy a very

energy

efficient wood stove.

Followers of the Prius method will

jump on a catalytic wood stove, an innovation that will lower their

emissions and increase their burning efficiency. On the negative

side, catalytic wood stoves are extremely expensive, and the catalyst

will have to be replaced in two to six years, which has environmental

repurcussions and makes a deep dent in your pocketbook.

Middle of the road wood stove

buyers will gravitate to Energy Star

non-catalytic wood stoves. The use of baffles, firebox

insulation, and preheated combustion air combine to make these wood

stoves nearly as efficient as the catalytic versions and at least 60%

more efficient than old-fashioned wood stoves. Like the catalyst

in a catalytic wood stove, the baffle in a non-catalytic wood stove may

need to be replaced from time to time, but my understanding is that

this replacement is considerably less expensive.

Middle of the road wood stove

buyers will gravitate to Energy Star

non-catalytic wood stoves. The use of baffles, firebox

insulation, and preheated combustion air combine to make these wood

stoves nearly as efficient as the catalytic versions and at least 60%

more efficient than old-fashioned wood stoves. Like the catalyst

in a catalytic wood stove, the baffle in a non-catalytic wood stove may

need to be replaced from time to time, but my understanding is that

this replacement is considerably less expensive.

Then there's the

penny-pinching route, which I'm seriously

considering. Even the most efficient wood stoves only burn at

peak efficiency if you keep your fire hot, and the smallest Energy Star

wood stoves seem to clock in at about 60,000 BTU. Although it's

only a rough guide, many sources suggest planning on 50 to 55 BTU per

square foot in the extreme north of the U.S., 30 to 35 BTU per square

foot in the deep south, and around 40 to 45 BTU per square foot here in

southwest Virginia. Using those numbers, we should be in the

market for a 20,000 to 22,500 BTU wood stove for our 500 square foot

trailer, since we'd lose a lot of efficiency by damping down a larger

wood stove. Even if a tiny stove is much less efficient than a

big Energy Star stove, we'd burn less wood and make less pollution with

the penny-pinching method. Plus, tiny wood stoves are

considerably cheaper, as I'll explain tomorrow.

| This post is part of our Wood Stove lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Step 1 in making room for the

new

woodstove is to take down the old water tower.

We've decided to make a tiny

addition to the trailer to ease wood stove installation. The four

foot by two foot "room" will give us a bit more air space around the

stove inside and (more importantly) will allow us to send the stove

pipe straight up and then out a roof built around it, rather than

risking causing leaks by cutting a hole in the trailer roof. The

supreme ease with which you can extend the wall by a couple of feet is

one of my favorite parts of trailer

life.

We've decided to make a tiny

addition to the trailer to ease wood stove installation. The four

foot by two foot "room" will give us a bit more air space around the

stove inside and (more importantly) will allow us to send the stove

pipe straight up and then out a roof built around it, rather than

risking causing leaks by cutting a hole in the trailer roof. The

supreme ease with which you can extend the wall by a couple of feet is

one of my favorite parts of trailer

life.

While

Mark is making space outside, I took on the task of

clearing space inside. Kitchen remodeling, Walden Effect style,

consists of finding room for endless sacks of sweet potatoes and

garlic. Oh, and can I fit a few more butternut squash on that

shelf? I was very proud of myself for being able to take down

shelves from one wall and put them up in a new order on the other wall

--- an easy task for Mark, but I wouldn't have even known where to

start when faced with such a project just four years ago.

Everything I build could be better, but I don't mind living with my

imperfections since each is a lesson in self-sufficiency.

If

you're in the market for a tiny wood stove, the choices are relatively

limited. The smallest stove I've found among mainstream stores is

the Vogelzang

Lit'L Sweetie,

$199 from Northern Tool and Equipment. This cast iron stove is

marked on their website as being eligible for the federal tax credit,

which suggests that it must be efficient, but I can't seem to find any

efficiency data on the internet and the model is small enough that it

is exempt from EPA certification. On the other hand, even this 19

by 25 by 23 inch stove feels too big for us since it's rated at 63,801

BTU. Various reviews also suggest that it isn't very well put

together and may leak smoke or be unsafe.

If

you're in the market for a tiny wood stove, the choices are relatively

limited. The smallest stove I've found among mainstream stores is

the Vogelzang

Lit'L Sweetie,

$199 from Northern Tool and Equipment. This cast iron stove is

marked on their website as being eligible for the federal tax credit,

which suggests that it must be efficient, but I can't seem to find any

efficiency data on the internet and the model is small enough that it

is exempt from EPA certification. On the other hand, even this 19

by 25 by 23 inch stove feels too big for us since it's rated at 63,801

BTU. Various reviews also suggest that it isn't very well put

together and may leak smoke or be unsafe.

Moving down to smaller

stoves, you'll find the Two, Three, Four, and Five Dog

Stoves.

These stoves are made for use in tents and yurts, so I find them very

difficult to compare to more traditional stoves. The Four Dog

Stove ($305 once you factor in shipping) has a 15.5 by 11.5 by 24 inch

firebox

and "will heat up a 14' X 16' wall tent at -30". Its smaller

siblings heat progressively smaller spaces. All of the stoves in

the Four Dog line have baffles and an airtight gasketed door, which

make the stoves more efficient and safer while also

concentrating heat on a hot spot on the surface for cooking. On

the negative side, the stoves are light-weight with walls made of 3/32

inch hot rolled steel, no fire bricks, and aren't designed to preheat

their combustion air, so they lack some efficiency and maybe

longevity. I wonder if it

would be possible to take a Four Dog Stove (which I suspect might be

too big for us) and retrofit it with fire bricks to turn it into a more

efficient model with a smaller firebox.

Moving down to smaller

stoves, you'll find the Two, Three, Four, and Five Dog

Stoves.

These stoves are made for use in tents and yurts, so I find them very

difficult to compare to more traditional stoves. The Four Dog

Stove ($305 once you factor in shipping) has a 15.5 by 11.5 by 24 inch

firebox

and "will heat up a 14' X 16' wall tent at -30". Its smaller

siblings heat progressively smaller spaces. All of the stoves in

the Four Dog line have baffles and an airtight gasketed door, which

make the stoves more efficient and safer while also

concentrating heat on a hot spot on the surface for cooking. On

the negative side, the stoves are light-weight with walls made of 3/32

inch hot rolled steel, no fire bricks, and aren't designed to preheat

their combustion air, so they lack some efficiency and maybe

longevity. I wonder if it

would be possible to take a Four Dog Stove (which I suspect might be

too big for us) and retrofit it with fire bricks to turn it into a more

efficient model with a smaller firebox.

If

we want to spend an arm and a leg, the Jotul

F 602

is just the right size for us, with a 19 by 12.5 inch firebox

(with a guestimated third dimension of around 16 inches) and a heat

output of 28,000

BTU. Due to its baffles, the stove is 75% efficient, has low

emissions

of 5.2 g/hr, and is eligible for the federal tax credit. The

price

seems to be a bit harder to figure out, but one review lists it at $700

(which would end up costing us $490 after the tax credit.) One

website notes that this model is "alcove approved", perhaps because of

its heat shield, which makes me wonder if it might be the safest of the

options to put in a mobile

home. The

Jotul stove even has a

cookplate on top, which is something I'm yearning for as a backup

cooking option.

If

we want to spend an arm and a leg, the Jotul

F 602

is just the right size for us, with a 19 by 12.5 inch firebox

(with a guestimated third dimension of around 16 inches) and a heat

output of 28,000

BTU. Due to its baffles, the stove is 75% efficient, has low

emissions

of 5.2 g/hr, and is eligible for the federal tax credit. The

price

seems to be a bit harder to figure out, but one review lists it at $700

(which would end up costing us $490 after the tax credit.) One

website notes that this model is "alcove approved", perhaps because of

its heat shield, which makes me wonder if it might be the safest of the

options to put in a mobile

home. The

Jotul stove even has a

cookplate on top, which is something I'm yearning for as a backup

cooking option.

I estimate that any of

these stoves would cut our wood use (and the associated labor) at least

in half. However, we would have to install one stove in the

trailer and another one in the East Wing, so the up front cost would be

pretty steep. I'm pondering a Two Dog Stove in the tiny East Wing

($240) and a Jotul F 602 or Four Dog Stove in the trailer, and am

counting on spending a few more hundred dollars on associated hardware

for the safest installation (and we might even splurge beyond that to

pay for a professional to install the stove in the trailer.) If

we went the most expensive but most efficient route (the Jotul), it

would probably take us about six years to pay back the cost through

wood savings, whereas we'd pay ourselves back in five years using the

cheaper option.

| This post is part of our Wood Stove lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Edited to add:

Learn how to safely install an energy-efficient wood stove in a moibile

home in Trailersteading. Now available for

$1.99 on Amazon.

These railroad ties were in pretty

bad shape when we got them 5 years ago.

These railroad ties were in pretty

bad shape when we got them 5 years ago.

Two of them broke off at

ground level while I was working on digging them out.

Not the best option for

making such a tower, but a whole lot cheaper than buying new lumber. I

remember paying 5 bucks apiece for these from a guy who owns a junk

yard.

"Why mulch the garden

now?" Daddy asked when he was visiting in October. "Weeds aren't

going to grow this late in the season." It turns out that weeds were growing, and if I'd had my

act together, it would have been smarter to get the garden mulched down

by the end of September when a lot of the winter weeds

germinated. Your garden may have different trouble plants, but

these are our three most common winter weeds.

Common

Chickweed (Stellaria

media) loves

bare, disturbed ground and will quickly spread its runner-like stems

across your garden. Identify this alien species by the rosette

form of its growth, by the small, roundish leaves, and the tiny white

flowers. Although chickweed is a pain in the butt to hack out of

half-frozen ground when you want to plant your early spring crops, if

you do let the chickweed get ahead of you at least you'll know that the

chickweed greens are beloved by your flock of chickens. In fact, I've read

that common chickweed is often eaten by humans either in salad or as a

cooked green.

Common

Chickweed (Stellaria

media) loves

bare, disturbed ground and will quickly spread its runner-like stems

across your garden. Identify this alien species by the rosette

form of its growth, by the small, roundish leaves, and the tiny white

flowers. Although chickweed is a pain in the butt to hack out of

half-frozen ground when you want to plant your early spring crops, if

you do let the chickweed get ahead of you at least you'll know that the

chickweed greens are beloved by your flock of chickens. In fact, I've read

that common chickweed is often eaten by humans either in salad or as a

cooked green.

Purple Dead Nettle (Lamium

purpureum) is

easy to identify when it blooms in the early spring --- the top few

leaves turn purplish to set off the pink flowers, and the square stem

proclaims it to be a member of the mint family. At this time of

year, the non-stinging dead nettle takes a bit more care to identify,

but once you feel the fuzzy leaves, you'll realize few other wild

plants have the same gestalt. Like nearly all of our garden

weeds, Purple Dead Nettle hails from Europe, probably introduced for

the edible young leaves that can be eaten like chickweed.

Although Purple Dead Nettle does like to fill up the winter garden, the

flip side of the coin is that it will bloom even in the winter if the

weather is mild, providing food for honeybees during warm days.

Purple Dead Nettle (Lamium

purpureum) is

easy to identify when it blooms in the early spring --- the top few

leaves turn purplish to set off the pink flowers, and the square stem

proclaims it to be a member of the mint family. At this time of

year, the non-stinging dead nettle takes a bit more care to identify,

but once you feel the fuzzy leaves, you'll realize few other wild

plants have the same gestalt. Like nearly all of our garden

weeds, Purple Dead Nettle hails from Europe, probably introduced for

the edible young leaves that can be eaten like chickweed.

Although Purple Dead Nettle does like to fill up the winter garden, the

flip side of the coin is that it will bloom even in the winter if the

weather is mild, providing food for honeybees during warm days.

Hairy

Bittercress (Cardamine

hirsuta) always

cheers me up since it's the first flower I see most years, blooming as

early as February or March. Although the bittercress grows its

leaves in a rosette, they are very different from chickweed, never

taking on the sprawling appearance and usually reaching only two or