archives for 01/2010

(I know Mark has already told you some of

this, but it's so momentous I wanted to post about it too!)

(I know Mark has already told you some of

this, but it's so momentous I wanted to post about it too!)

Mark and I finally got away from the farm Wednesday to visit my family

in Bristol. When we got home, we were thrilled to see the

powerline back in place atop its poles! We scurried into the

trailer...only to discover that the juice was still off.

Remember how I

lost faith on day 1 of the outage? Now it was Mark's

turn. When the electricity was still off on Thursday morning, I

could see his spirits plummeting into his (cold, wet) boots. It

was too rainy outside to heat anything up on the wood stove for lunch,

so we shivered in the kitchen, eating cold chicken sandwiches and

bemoaning our fate.

Then I gasped.

"Oh, no!" Mark responded. "What's wrong now?"

Speechless, I pointed down the hall to where our CFL had flickered into

light. "Look, Mark! Electricity!!!!!!"

We stared in rapture at the glowing bulb for a couple of minutes, then

jumped into action. Mark plugged in the stove fan and freezer

while I started up the fridge and internet. I turned on the

drinking water pump and filled

up our emergency milk jugs of water, then we headed out to pump

water from the creek to fill the thousand

gallon washing-water tank. (We'd been caught, very

unfortunately, with it nearly completely empty, which really made the

outage more difficult than it should have been.)

Next, Mark plugged in the

golf cart while I filled pots of water to heat on the stove.

Near instant hot water, and plenty of it! After skimping for

nearly two weeks, washing each day's dishes in a scant gallon of melted

snow, I was so

excited that I filled our sink with gallons and gallons worth, even

though there weren't really that many dishes.

Next, Mark plugged in the

golf cart while I filled pots of water to heat on the stove.

Near instant hot water, and plenty of it! After skimping for

nearly two weeks, washing each day's dishes in a scant gallon of melted

snow, I was so

excited that I filled our sink with gallons and gallons worth, even

though there weren't really that many dishes.

Before I was able to calm down enough to check my email, I had to twirl

around outside in the snow, singing at the top of my lungs,

"Elec-tri-ci-ty! Light! Heat! Water!"

My weather-forecaster buddy warns that bitter cold weather is on its

way tonight, with all next week slated to stay below freezing.

Right at this instant, though, I can't muster any doom and gloom at all.

This post is part of our Two Weeks Without Electricity series.

Read all of the entries:

|

To

hear Michael Phillips write about it, you would think that apple trees

are fortunate to make it through the year, let alone set fruit.

He

fights a slew of insect pests along with fungal, bacterial, and viral

diseases, struggling to end up with a harvest of fruits pretty enough

to sell to his customers.

To

hear Michael Phillips write about it, you would think that apple trees

are fortunate to make it through the year, let alone set fruit.

He

fights a slew of insect pests along with fungal, bacterial, and viral

diseases, struggling to end up with a harvest of fruits pretty enough

to sell to his customers.

I feel lucky to be a

homesteader who cares mostly about taste. Still, I plan to take

some of his preventative advice to heart. We're slowly cutting

down nearby cedar trees and would do the same if we had nearby

crabapples or hawthorns since all three serve as alternate hosts for

apple diseases.

Once our trees are

bearing, we'll rake up their leaves in the fall and compost them since

fallen apple trees can innoculate the tree with diseases the next year

if left in place. While thinning our hypothetical fruits, we'll

be careful to remove insect-damaged apples and will also rake up

June-dropped fruits to feed to our chickens. Old timey apple

farmers used to run poultry and swine under their trees during that

period --- maybe we'll have pigs

by then and can work something out.

For now, though, we're

in that golden period before the apple trees mature when we can

fantasize that our fruits won't fall prey to any diseases or

pests. I'll dream while I can, and remember The

Apple Grower for

organic tips when the time comes.

| This post is part of our Growing Organic Apples lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Happy New Year!

We started 2010 on a level footing by plugging away at our latest storage

building project today.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

A

few quick book-keeping notes for the new year....

A

few quick book-keeping notes for the new year....

First

of all, thank you

to everyone who posted comments this month to enter our daffodil

giveaway! I've

really enjoyed hearing all of your feedback and getting to know you

better. The grand prize winner is my father --- I swear it was

random! :-) We had a really good month selling automatic chicken waterers, so there were only about 20

daffodil bulbs left to give away. I'm tossing in some poppy seeds

to round his

flower bed out. Stay tuned for another giveaway soon!

On

another vaguely

chicken-related topic, I'm posting a long series about chicken tractors

on our chicken blog this month. Some of

the posts you've already seen over here while others are totally

new. My goal is to really think through all of the chicken

tractor designs we've used in the past so that our next tractor will be

awesome. I hope my musings will also help other folks design a

cheap and effective tractor and get those hens out of the mud.

You can subscribe to the RSS feed of that blog just like this one --- I

look forward to seeing some of you over there!

Finally,

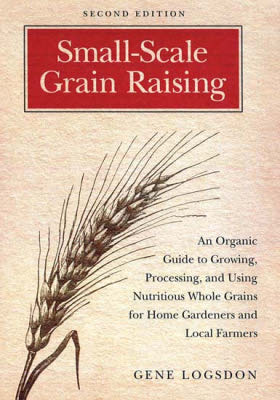

I was going to post a review of the best non-fiction books I'd

read in 2009 over here, but instead decided to finally set myself up a

Goodreads account.

If I stick to it, I plan to post all of my fiction and non-fiction book

ratings over there (although I'll keep posting lunchtime series over

here.) Feel free to friend me and share your own books!

And have a great 2010!

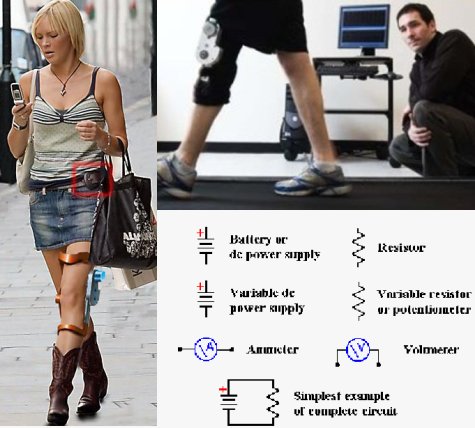

The

University of

Michigan has made some impressive strides in the area of human

generated electricity.

The

University of

Michigan has made some impressive strides in the area of human

generated electricity.

Their latest prototype is a knee brace that

harnesses the energy normally lost when the knee is bent. It can

produce up to 5 watts of power, which would be enough juice to run 10

mobile phones.

It would be interesting to see how much electricity the average person generates

over the course of a day?

Last

week, I was paging through old blog entries from this summer and

literally couldn't remember the earth looking so green. On the

south side of the trailer, the ground is still covered by snow where

it's shaded by the hill, and the rest of the world is mostly

brown. I watch deer pulling honeysuckle out of trees and dream of

a big, black bull calf doing the same in search of green leaves.

Last

week, I was paging through old blog entries from this summer and

literally couldn't remember the earth looking so green. On the

south side of the trailer, the ground is still covered by snow where

it's shaded by the hill, and the rest of the world is mostly

brown. I watch deer pulling honeysuckle out of trees and dream of

a big, black bull calf doing the same in search of green leaves.

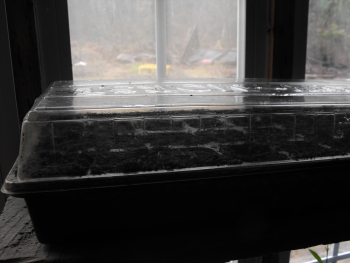

How

do I relieve winter gardener's blues? Luckily, I've got some

house plants in need of attention. My citrus trees (dwarf

Meyer lemon and

dwarf tangerine) have sunken down in their pots over the long growing

season and need a new infusion of stump dirt. I also have a

rosemary in need of potting --- one of the six sprigs I got from my

father finally sprouted roots.

How

do I relieve winter gardener's blues? Luckily, I've got some

house plants in need of attention. My citrus trees (dwarf

Meyer lemon and

dwarf tangerine) have sunken down in their pots over the long growing

season and need a new infusion of stump dirt. I also have a

rosemary in need of potting --- one of the six sprigs I got from my

father finally sprouted roots.

So I climb the hill

halfway to the cars, heading straight to my

favorite, hollow beech.

This old beauty churns out around seven or eight gallons of stump dirt

every year, which I scoop out with our yellow-handled shovel, savoring

every teaspoonful. I chose a warm day so that the stump dirt

would be shovelable, but that means the driveway is too wet to drive

on. So I lug the dirt home in five gallon buckets. It's all

worthwhile, though, when I get to sink my fingers into rich soil, the

combined scent of actinomycetes and rosemary smelling as good as baking

bread.

10 years ago I found this hand cranked radio in the discount bin of a

Radio Shack just after the Y2K hype was settling down. Most hand

powered devices use a small dynamo that charges an even smaller battery

that will eventually stop holding a charge over time. This unit uses a

medium sized spring that slowly releases its mechanical power after the

energy is stored in the form of hand cranks. It will hold up to 40

cranks, which equals about 20 minutes of power.

The radio is very basic and also works on a little solar cell that is embedded in the top, but only if you place it directly in the sun. I like to have it on hand as a back up power source and someday dream of building a larger version that might be more capable of powering something like our modem and router and maybe a laptop or two. It only produces enough electricity for a small flashlight, which can be considered night time entertainment during a power outage.

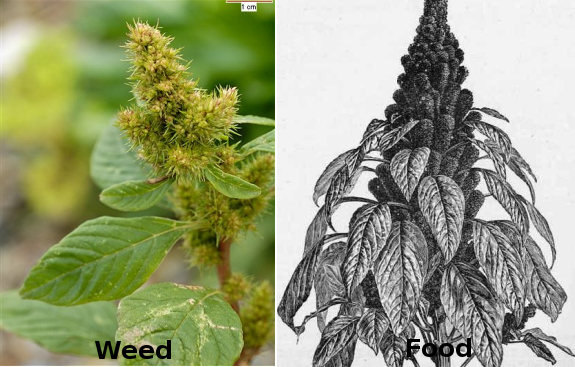

In response to my post

on easy to grow

grains, two of you

asked whether I was concerned about amaranth being a weed. I

decided to do a bit of research and disentangle fact from fiction.

The

word "amaranth" can be used to refer to any plant in the genus Amaranthus --- 70 species total.

Some species are weeds and some are useful foods dating back thousands

of years.

The

weed species are generally known as pigweed and include Amaranthus

albus, A.

blitoides, A.

hybridus, A. palmeri, A.

powellii, A.

retroflexus, A.

spinosus (the one

that wreaks havoc on my bare feet in the summer), A.

tuberculatus, and

A. viridis. I wonder whether any

of these plants were also grown by Native Americans for food,

accounting for their widespread growth across the U.S.?

Unfortunately, I couldn't find any data on this.

On

the other hand, A.

caudatus, A.

cruentus, and A.

hypochondriacus are grown

as food plants,

with the latter being the species most often grown in the U.S.

Amaranth was grown by the Incas, the Aztecs, and various Native

Americans in what is now Mexico until the conquistadores came and

nearly wiped amaranth out of existence. Nowadays, you can find

the seeds of the edible varieties for sale from some of the more

heirloom-inclined seed companies.

We

opted to buy some Manna de Montana Amaranth from Seeds of Change --- I'll let you know how it

goes as the growing season progresses. Meanwhile, I splurged on a

few more experimental crops --- Hungarian Blue Breadseed Poppy, Temuco

Quinoa, Urd Sprouting Bean, Black Kabouli Garbanzo Bean (since we have

to drive an hour to get these in the store), Hullless Oats (thanks for

the tip, Sena!), and Afghani Sesame. I figure at least one or two

should work out and make it onto our list of regulars!

My

brother posted about the last decade of his life so vibrantly (and

succinctly) that I decided to give it a go. The last decade fills

up pretty much a full third of my life to date and my entire

post-college adulthood --- yikes!

My

brother posted about the last decade of his life so vibrantly (and

succinctly) that I decided to give it a go. The last decade fills

up pretty much a full third of my life to date and my entire

post-college adulthood --- yikes!

2000 started with the

last few months of my senior year at college. Although my

freshman, sophomore, and junior years had been life-changing and fun,

my senior year was stressful and angsty. By the beginning of

July, I was glad to see campus disappear and to instead be hopping on a

plane to England (then Australia, then Costa Rica) for a solid year of

camping and drawing plants.

Although

I'd dreamed of living on a homestead in the woods ever since I was

ripped from our family farm in elementary school, I think my world

travel year cemented the deal. I backpacked the whole time, and

was shocked to return home to the U.S. and discover the size of stores

and supermarkets, and to see the many boxes of possessions I had

waiting for me in my mom's basement. Why would I need all of this

stuff when I'd happily lived with just fifty pounds of camping and

drawing equipment for the last year?

Although

I'd dreamed of living on a homestead in the woods ever since I was

ripped from our family farm in elementary school, I think my world

travel year cemented the deal. I backpacked the whole time, and

was shocked to return home to the U.S. and discover the size of stores

and supermarkets, and to see the many boxes of possessions I had

waiting for me in my mom's basement. Why would I need all of this

stuff when I'd happily lived with just fifty pounds of camping and

drawing equipment for the last year?

| This post is part of our Decade in Review series.

Read all of the entries: |

Cutting through difficult nails within a tight space like this is where

these reciprocating

saws really shine. The medium sized metal blade allows you to bend

it at an angle, just don't bend it too much or it will kick like a mule.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

Daddy told me that it

looks fishy for him to win the giveaway, and one of our regular readers

agreed. :-) So the daffodils will go

to whoever of the following top five randomly selected commenters emails me their mailing address

first:

Shannon (who got two votes from the random number generator!)

Vester

Heather

Everett

Among

the folks whose blogs I read, several people have made a New

Year's resolution to post at least three sentences every day on their

blogs. I, on the other hand, have a hard time limiting myself to

two

posts a day. :-) I didn't want to "waste" an entry on this, so

here's

a quick note that's not an entry, really! (See, no picture!!)

I'd

be the first one to tell you that our homemade

storage building has growing pains.

Although I've read a lot of books and websites, this is the first time

I've ever put screw to 2x4, and it shows.

I'd

be the first one to tell you that our homemade

storage building has growing pains.

Although I've read a lot of books and websites, this is the first time

I've ever put screw to 2x4, and it shows.

We probably could have

the whole thing done by now if we knew what we were doing, but we've

still got two walls to raise and the roof to put on before we even

start on the interior. Still, I can feel the building process

picking up momentum as we repeat steps we've figured out in the past.

Monday, Mark let me try

my hand at framing a wall. Those square bits that come in the

screw boxes make it much easier for a novice like me to drive screws

without stripping the heads.

I nearly finished the

half wall section I was working on before I ran out of lumber.

Unfortunately, we had to call it quits for the day since we got a flat

driving the golf cart through ice to the cars where

the rest of the 2x4s are stored. Mark's teaching me that things

happen on a farm --- you just have to roll with it and allow plenty of

extra time to get projects done!

Read our ebook about quitting your job and becoming financially independent.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

Although

backpacking gave me a glimpse of simplicity, I didn't have any

money to buy a farm, so I instead spent the next few years wandering

around in other peoples' woods. Every year, I moved to a new

property

where I identified the plants and animals and told the owners what they

were doing right or wrong. Some of my hosts turned out to be my

best

friends, and I got all of my maternal urges out of my system by helping

with one set of kids who I still adore (even though they're all

grown up now!)

Although

backpacking gave me a glimpse of simplicity, I didn't have any

money to buy a farm, so I instead spent the next few years wandering

around in other peoples' woods. Every year, I moved to a new

property

where I identified the plants and animals and told the owners what they

were doing right or wrong. Some of my hosts turned out to be my

best

friends, and I got all of my maternal urges out of my system by helping

with one set of kids who I still adore (even though they're all

grown up now!)

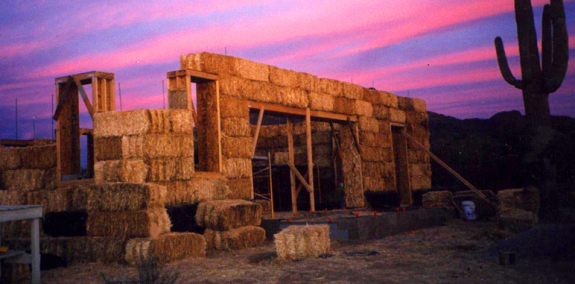

In 2003, I finally

achieved the goal I'd been saving for and dreaming of for so long --- I

bought 58 acres of swamp and hillside about an hour from the farm I

grew up on. With no experience under my belt, I took my father's

advice and decided to build a little house by hand, first tearing down

the old house on the property to get some supplies.

Crowbarring on

winter days, I came down with carpal tunnel and ended up dropping that

dream for the time being.

In 2003, I finally

achieved the goal I'd been saving for and dreaming of for so long --- I

bought 58 acres of swamp and hillside about an hour from the farm I

grew up on. With no experience under my belt, I took my father's

advice and decided to build a little house by hand, first tearing down

the old house on the property to get some supplies.

Crowbarring on

winter days, I came down with carpal tunnel and ended up dropping that

dream for the time being.

| This post is part of our Decade in Review series.

Read all of the entries: |

I had my 2nd flat tire of the week just as I got yesterday's fixed.

The first one was due to a sharp tree root jutting out of the frozen

ground and jabbing itself into the side wall, but today's deflation could

have been avoided if I'd had an inner tube in the tire, which it now

has.

At least we got all the 2x4s shuttled back to our storage

building project before this next storm sets in.

Today's

homesteading tip originated with my mother, I swear, not with a

homeless person. On a farm, it's awfully easy to get your boots

wet even if they're waterproof. Maybe the world is full of deep,

damp snow (like last week) and clods drop down the back of your

heel. Maybe you slip off the creek bank while sawing through a

grapevine (like this week) and your foot submerges in frigid

water. Either way, the worst thing you can do is keep working

with wet feet. But if you don't have a good pair of spare boots,

what do you do?

Today's

homesteading tip originated with my mother, I swear, not with a

homeless person. On a farm, it's awfully easy to get your boots

wet even if they're waterproof. Maybe the world is full of deep,

damp snow (like last week) and clods drop down the back of your

heel. Maybe you slip off the creek bank while sawing through a

grapevine (like this week) and your foot submerges in frigid

water. Either way, the worst thing you can do is keep working

with wet feet. But if you don't have a good pair of spare boots,

what do you do?

Take a plastic grocery

store bag and wrap it around your dryly socked foot. Then slide the whole

shebang into your boot --- this has the added bonus of making boots

slide on even easier! The grocery store bag separates your foot

from the damp boot wall until the evening, when you can set your

footware by the stove to dry. Dry feet!

When

I had to put my farm dream on hold, I ended up

moving back in with one of my inventory families, to help with those

same kids. The family matriarch had plans for me, though I didn't

know

it. She (Sue Ella) and her sister (Rose Nell) were playing

matchmaker and believed that Rose Nell's son and I were perfect for

each other. Sue Ella tried every trick in the book

to get us to meet, but I scurried the other way just as quickly as

possible. He'd be coming down for Thanksgiving? Sorry --- I

have to

go visit my father! You want me to help him drive your son's

possessions across country? Are you nuts?! Even though I'd

traveled

the world, I'd never kissed a boy --- women in my mother's family tend

to be late bloomers --- and I didn't particularly see why I should

start now.

When

I had to put my farm dream on hold, I ended up

moving back in with one of my inventory families, to help with those

same kids. The family matriarch had plans for me, though I didn't

know

it. She (Sue Ella) and her sister (Rose Nell) were playing

matchmaker and believed that Rose Nell's son and I were perfect for

each other. Sue Ella tried every trick in the book

to get us to meet, but I scurried the other way just as quickly as

possible. He'd be coming down for Thanksgiving? Sorry --- I

have to

go visit my father! You want me to help him drive your son's

possessions across country? Are you nuts?! Even though I'd

traveled

the world, I'd never kissed a boy --- women in my mother's family tend

to be late bloomers --- and I didn't particularly see why I should

start now.

When Sue Ella finally

pinned me down in 2005, she and Rose Nell didn't trust us to go on this

first,

blind date on our own. Intead, Sue Ella put me in her car, Rose

Nell

put Mark in her car, and all four of us met at a restaurant in the

middle. After our date, we browsed for a while in the Dollar

Store,

and went our separate ways. In fact, Mark fled all the way to New

Mexico, but he emailed me and slowly wiggled his way through my

defenses and into my heart. Four months later, we kissed for the

first

time while listening to a chorus of spring peepers. When we

kissed again

in a cave, my knees went weak, and 17 months later we moved onto the

land. Mark had been the missing link in my farm dream, even

though I

hadn't known it at the time.

| This post is part of our Decade in Review series.

Read all of the entries: |

Using this utility pump to fill a proper water container feels like a

huge improvement over last

year's 5 gallon bucket method. The biggest downside was lifting the

bucket back out once you filled it as full as you dared.

This

is my new wall --- I'm so proud of making it (nearly) all by

myself. That said, I should have measured a little better to make

it "square" (a perfect rectangle) so that we didn't have to take it

back apart to get the window to fit....

This

is my new wall --- I'm so proud of making it (nearly) all by

myself. That said, I should have measured a little better to make

it "square" (a perfect rectangle) so that we didn't have to take it

back apart to get the window to fit....Next time, I'm not going to assume that the diagonals being off by a quarter of an inch is okay. Unsurprisingly, Mark decided he would be in charge of putting in the door, which is the next step.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

The last three years of

the decade, we got the farm running and I learned to garden. I've

always been torn in several directions --- between art and writing on

one hand and biology on the other. The farm --- and this blog ---

turned out to be the junction of the two fields, letting me create

beauty and play with plants all at once.

The last three years of

the decade, we got the farm running and I learned to garden. I've

always been torn in several directions --- between art and writing on

one hand and biology on the other. The farm --- and this blog ---

turned out to be the junction of the two fields, letting me create

beauty and play with plants all at once.

After moving to the farm, I first worked

as a part-time professor at a local college, then as an employee at a

non-profit organization. Both of these jobs were fun in parts but

also

stressful. Only last year did we reach what had been Mark's dream

all

decade --- such a simplicity of needs and diversification of income

sources that we could both quit our jobs and work for

ourselves.

Meanwhile, Mark and I

grew together in delightful ways. Every day seemed (and still

seems)

to be better than the last, and his kisses still make me weak at the

knees. In December 2008, we finally decided to get legal, so we went

to the courthouse and got hitched. Last year, we celebrated

with our family and friends with a

picnic at the park.

| This post is part of our Decade in Review series.

Read all of the entries: |

The 6th wall section is now up and looking like a storage

building.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

We

kicked off Mark appreciation week on Thursday with a trip to the big

city to see Avatar in 3D. Even though the story had some flaws,

the world building and visuals were so stunning that by the time we

stepped back out the door, we were shocked to see snow falling on a

dark, cold night.

We

kicked off Mark appreciation week on Thursday with a trip to the big

city to see Avatar in 3D. Even though the story had some flaws,

the world building and visuals were so stunning that by the time we

stepped back out the door, we were shocked to see snow falling on a

dark, cold night.

The roads get dicey fast

in the mountains, and it took us about two hours to drive what usually

takes 45 minutes. On the north side of the hills, the snow that

knocked out our power three weeks ago is still hanging on, but is

now invisible under another layer of white. Luckily, Mark's an

experienced driver and we made it home with no mishaps.

The world has been white and frozen for so long that I feel like I've

moved to New England for the winter!

What do I foresee in the

twenty-teens? Honestly, if you'd asked me what my life would be

like a

decade later in 2000, the only part I could have imagined would have

been the farm, so I don't think my predictions should hold much

weight. But I can tell you what I'd like to see.

What do I foresee in the

twenty-teens? Honestly, if you'd asked me what my life would be

like a

decade later in 2000, the only part I could have imagined would have

been the farm, so I don't think my predictions should hold much

weight. But I can tell you what I'd like to see.

In ten years, I hope

that Mark and I will still be living on this same farm, but hopefully a

slightly more

advanced farm with a pasture or two,

a growing forest

garden, and maybe

even an indoors bathtub and outdoors greenhouse. By then, I want

to have streamlined the garden process to cut back a bit on the time we

spend on repetitive chores like weeding and increase the time we spend

on the more fun part. Maybe by then we'll

truly be food independent, having figured out grains, oil, and a few

more meats.

I hope to have built my

social network a little more by then. My college years were

blissful

in that regard, and ever since I've been looking for a similar

community where I can feel accepted and at ease. We're slowly

making

friends in the area now that we're settled, so hopefully this community

will grow organically with time.

Last decade, I found

Mark --- he and the farm were really the highlights of the 2000s.

This

decade, I hope that we'll find someone to back us up on the farm when

we go on our explorations. Whether that will be a live-in

apprentice,

a nearby farmer who we can trade caretaking with, or something else

entirely, I'll leave

up to the toss of the dice.

Last decade, I found

Mark --- he and the farm were really the highlights of the 2000s.

This

decade, I hope that we'll find someone to back us up on the farm when

we go on our explorations. Whether that will be a live-in

apprentice,

a nearby farmer who we can trade caretaking with, or something else

entirely, I'll leave

up to the toss of the dice.

Lately, I've started to

find a good balance of computer work, physical work, and relaxation

--- hopefully by the end of the decade I'll have it as well figured out

as Mark does. Maybe this decade will be all about balance.

| This post is part of our Decade in Review series.

Read all of the entries: |

![]()

A new layer of snow and some frigid temperatures kept us working inside

today. Brrrrr.

The movie Avatar

was a fantastic initiation into the new realm of 3D cinema. Science

fiction is the perfect genre for this new technology and Avatar was a

non stop ride that remains with you long after the house lights come on. A great way to celebrate the beginning of my 41st year.

Last

year, I posted about the most

delightful, fluffy, completely whole wheat bread recipe that counts on wheat gluten to increase the fluff

factor. Ever since then, folks have been asking me, "Isn't gluten

bad for you?"

Last

year, I posted about the most

delightful, fluffy, completely whole wheat bread recipe that counts on wheat gluten to increase the fluff

factor. Ever since then, folks have been asking me, "Isn't gluten

bad for you?"

Some people are gluten

intolerant, which means that their bodies can't break down

gluten. If these folks eat foods containing gluten, they end up

with all kinds of health problems. On the other hand, gluten

isn't like trans-fat or any of the other components of food that cause

problems in everyone. If you don't have a gluten sensitivity, you

can dive right in with no problems!

Gluten is found

naturally in most grains, and is currently added to a long list of

other foods (including things like chocolate, soup, and potato

chips.) Basically, if you're not making an effort to be

gluten-free, you're almost certainly eating gluten on a regular

basis. As long as you aren't showing any gluten intolerance

symptoms, you might as well get in the habit of adding gluten to your

whole wheat bread for a tastier texture (and extra protein.)

The team at KMS

woodworks has made some interesting progress in bringing together a compact solar charger that can be used for several low

end power needs like a lap top. They are still in the testing stage,

but it looks like they might make them available for sale in the 300 to

350 dollar range in the not too distant future.

It would be worth that much to me if it could power our modem and both

lap tops for a few hours per day, especially during a power outage.

I really like the idea of having a portable off the grid option,

especially one that can be taken on a back pack to provide the power

for blog posts in some random ancient megalith site or more Mayan ruins.

I felt like such a wimp complaining, but it turns out that this weather really is out of the ordinary. There's a high pressure zone sitting on Greenland that's deflecting cold air into the U.S., a situation that hasn't been this extreme since 1950. But all's not lost --- Dr. Walter Meier of the National Snow and Ice Data Center wants us to know that “pretty much all of the Arctic is above normal." There, don't you feel better now?

We made it out this afternoon for a wonderful Christmas party that had

been rescheduled due to the Blizzard of 09.

A big thanks to Steve and Maxine for making such a fantastic chocolate cake and

helping to ring in my 41st year with a delicious bang.

You know when you're a

homesteading geek when...

- you go to a party and one of the big attractions is heading down into the basement to check out your host's stored produce...

- ...and all of your friends want to go too so you have to wait your turn.

Check out these homemade

shelves spaced apart with log sections. Very classy!

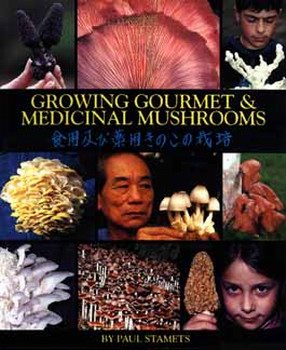

Regular

readers will remember how Mycelium

Running

sent me on a quest to propagate our edible mushrooms cheaply.

Paul Stamets' enthusiasm was so contagious that I've spent the last

nine months experimenting (with semi-success, which I'll discuss

later.) I reached a point where I needed to know more, so I

requested another one of his books on interlibrary loan.

Regular

readers will remember how Mycelium

Running

sent me on a quest to propagate our edible mushrooms cheaply.

Paul Stamets' enthusiasm was so contagious that I've spent the last

nine months experimenting (with semi-success, which I'll discuss

later.) I reached a point where I needed to know more, so I

requested another one of his books on interlibrary loan.

The 574 page Growing

Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms arrived at my library a few

weeks ago, and I've been reading it ever since. This book

is more technical than Mycelium

Running,

since the purpose is to provide the information new commerical growers

need to start their operation. The result is a book that is

slightly more tedious than Mycelium

Running, so I

can't recommend it to the general reader quite as whole-heartedly.

Nevertheless, Stamets'

enthusiasm shines through...along with so much

information that I'm struggling to pare it down to fit into two

lunchtime series! After reading the book from cover to cover, I

seem to have come up with twice as many questions as I started with,

but at least my original questions got answered.

This post is part of our Growing Gourmet Mushrooms lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

I puzzled over these strange ice formations for several minutes this

morning wondering how such a thing could have occured and where the

source of water was coming from.

I got my answer when I noticed Anna trying to hold back a serious case

of the giggles when I went back in. Turns out she thought it would be

nice to break off a couple sticks of ice and implant them as "dragon

horns" for the golf cart.

Baking

a cake on the farm is always an adventure. As the culmination of

Mark appreciation week, I decided on a rich chocolate cake that called

for seven eggs...only to look in the fridge and see a mere four

eggs! So I put on my boots and coat and headed outside in search

of three more.

Baking

a cake on the farm is always an adventure. As the culmination of

Mark appreciation week, I decided on a rich chocolate cake that called

for seven eggs...only to look in the fridge and see a mere four

eggs! So I put on my boots and coat and headed outside in search

of three more.

Usually, our nine hens

give us more eggs than we can eat, but this abnormal cold spell has

frozen the chicken

tractors in place and put our hens in a bad mood. Some days

this month, we've only gotten one egg between them. Would we get

lucky today?

I opened the nest box

door in the Plymouth Rock's tractor --- one egg. The young Golden

Comets are always good for at least an egg, so I wasn't concerned there

--- sure enough, one egg. But the last tractor has Golden Comets

who are finishing up their fourth year of life and are starting to slow

down in their laying. I opened the dryer

door and peeked in the last nest box...and breathed a sigh of

relief. One last egg!

Back

inside, I melted and beat and mixed. It was the first day this

year that had reached above freezing (even if only by a degree) and the

cats were feeling their oats. Every time the sun came out from

behind a cloud, both cats begged to be let out. Five minutes

later, the clouds closed and two chilly cats wanted in. My

routine was a bit like this --- turn on the microwave, let in a cat,

stir in the butter, let out a cat, measure the flour, let in a

cat. I think I didn't miss any ingredients (or cats.)

Back

inside, I melted and beat and mixed. It was the first day this

year that had reached above freezing (even if only by a degree) and the

cats were feeling their oats. Every time the sun came out from

behind a cloud, both cats begged to be let out. Five minutes

later, the clouds closed and two chilly cats wanted in. My

routine was a bit like this --- turn on the microwave, let in a cat,

stir in the butter, let out a cat, measure the flour, let in a

cat. I think I didn't miss any ingredients (or cats.)

Finally, the cake was

ready to hit the oven...except that I couldn't find the second round

cake pan. After a few minutes of looking around the kitchen with

a furrowed brow, I realized that I hadn't baked a double layer cake

since we stopped watering

the bees in a marble-filled cake pan. Out came the marbles,

in went the batter. Finally, the cake was in the oven and I could

relax. Happy birthday week, Mark!

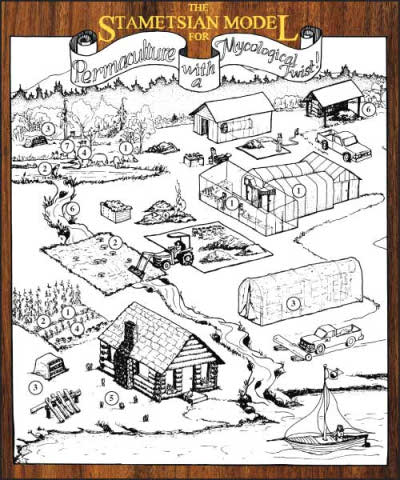

I checked out Growing Gourmet and Medicinal

Mushrooms

to learn a bit more about just what the title says, but I ended up

getting sucked in by the chapter on permaculture. (I know, what a

shock.) In the multi-use world of a working farm ecosystem, one

species stands out --- the King Stropharia (Stropharia rugosoannulata).

I checked out Growing Gourmet and Medicinal

Mushrooms

to learn a bit more about just what the title says, but I ended up

getting sucked in by the chapter on permaculture. (I know, what a

shock.) In the multi-use world of a working farm ecosystem, one

species stands out --- the King Stropharia (Stropharia rugosoannulata).

King Stropharia mushrooms are supposed to be both edible and tasty, but

their utility doesn't stop there. Paul Stamets reports food webs

that I wouldn't have believed coming from anyone else. I wasn't

so surprised to read that vegetables growing near the King Stropharia

grow better since I've read about how many

fungi team up with plant roots.

But I was shocked to hear that honey bees feed on the mushroom's

mycelium! Is this a possible method of providing our bees with

supplemental food other than sugar water?

Do bees feed on other species of fungi? I've personally seen our

workers harvesting something out of urine-soaked soil, and ever since

have been dubious of the the popular wisdom that bees just need

nectar/sugar and pollen.

As if that isn't enough of a reason to grow King Stropharia mushrooms,

Paul Stamets notes that the species is a potent bioremediator. He

sends runoff from his cow pasture through beds of wood chips full of

King Stropharia mycelium and sees clean water flowing out the other

end. Since Stamets has shown than the mushrooms can filter

bacteria and nitrogen out of contaminated water, I think that a King

Stropharia bed might be a perfect fit for our graywater leach field to

clean the water running out of our kitchen sink.

If you're as sold on the idea of King

Stropharia mushrooms as I am,

you'll probably want to know how to grow them. Once you get a

start from one of the mushroom companies (such as Paul Stamets'

Fungi

Perfecti), this species is reported to be extremely easy to grow

outside. Just rake fresh wood chips to a depth of one foot, add

five to twenty pounds of sawdust spawn per hundred square feet, water

for four days with a sprinkler, and keep the bed moist thereafter by

watering for half an hour in the morning and evening. If you

start your King Stropharia bed in the early spring, as is recommended,

you should see fruits by late July and continue to eat this

permaculture king until autumn weather cools the ground. Be sure

to pick the mushrooms young and expand your bed once it's in full swing

using the stem

butt method!

If you're as sold on the idea of King

Stropharia mushrooms as I am,

you'll probably want to know how to grow them. Once you get a

start from one of the mushroom companies (such as Paul Stamets'

Fungi

Perfecti), this species is reported to be extremely easy to grow

outside. Just rake fresh wood chips to a depth of one foot, add

five to twenty pounds of sawdust spawn per hundred square feet, water

for four days with a sprinkler, and keep the bed moist thereafter by

watering for half an hour in the morning and evening. If you

start your King Stropharia bed in the early spring, as is recommended,

you should see fruits by late July and continue to eat this

permaculture king until autumn weather cools the ground. Be sure

to pick the mushrooms young and expand your bed once it's in full swing

using the stem

butt method!

This post is part of our Growing Gourmet Mushrooms lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Anna and Lucy are the miter saw experts on this

job. I'm just backing them up with some heavy lifting and the

occasional two cents.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

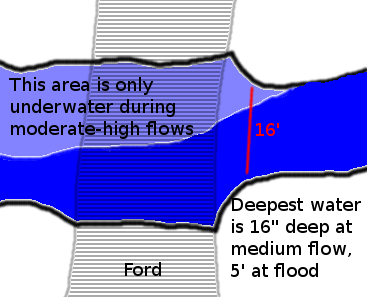

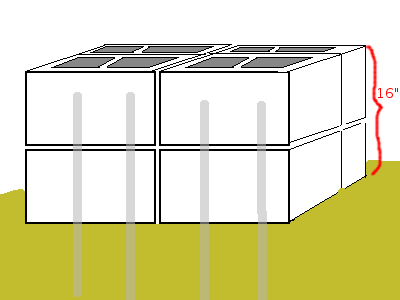

Halfway

through our homemade

storage building project, we opted to make a few changes. It

was originally envisioned as a workshop where Mark could build our chicken waterers, but once we decided to put

the exterior wood stove

inside, it made sense to repurpose it as Mark's bedroom/office

instead. In its new incarnation, though, the bed would have been

too close to the stove, and Mark wanted to raise his mattress up a bit,

so we decided to add another four feet to the length of the

structure.

Halfway

through our homemade

storage building project, we opted to make a few changes. It

was originally envisioned as a workshop where Mark could build our chicken waterers, but once we decided to put

the exterior wood stove

inside, it made sense to repurpose it as Mark's bedroom/office

instead. In its new incarnation, though, the bed would have been

too close to the stove, and Mark wanted to raise his mattress up a bit,

so we decided to add another four feet to the length of the

structure.

Tuesday,

we installed the floor for the bed addition, which felt a bit like

doing homework math problems --- you get a chance to correct the

misunderstandings you made the first time around and to cement the

proper method into your motor memory. This time, I

took Shannon's advice and put the rim joists on right away, which had the added benefit

of meaning that we didn't need to use expensive brackets.

Tuesday,

we installed the floor for the bed addition, which felt a bit like

doing homework math problems --- you get a chance to correct the

misunderstandings you made the first time around and to cement the

proper method into your motor memory. This time, I

took Shannon's advice and put the rim joists on right away, which had the added benefit

of meaning that we didn't need to use expensive brackets.

We

used salvaged three by fours for the floor joists. The sawmill

lumber wasn't exactly straight, but I suspect it'll be just as strong

as store bought two by sixes. After all, the three by fours

really are three inches by four inches, so they have nearly half again

as much cross-sectional area as the two by sixes.

We

used salvaged three by fours for the floor joists. The sawmill

lumber wasn't exactly straight, but I suspect it'll be just as strong

as store bought two by sixes. After all, the three by fours

really are three inches by four inches, so they have nearly half again

as much cross-sectional area as the two by sixes.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

Of

course, the meat of Growing

Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms

is information about how to take an existing mushroom and turn it into

thousands of new mushrooms. My previous lunchtime series about how

to cultivate edible mushrooms for free

explains most of the first step for turning an existing mushroom into a

mass of mycelium (the vegetative growth form of the fungus.)

Basically, you can either choose to start with spores

(like growing your mushroom from seed) or clone a mushroom you really like (like taking

cuttings of a grape vine.)

Of

course, the meat of Growing

Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms

is information about how to take an existing mushroom and turn it into

thousands of new mushrooms. My previous lunchtime series about how

to cultivate edible mushrooms for free

explains most of the first step for turning an existing mushroom into a

mass of mycelium (the vegetative growth form of the fungus.)

Basically, you can either choose to start with spores

(like growing your mushroom from seed) or clone a mushroom you really like (like taking

cuttings of a grape vine.)

The stem butt method of

cloning was the one mentioned in Mycelium

Running, and I

have to admit that this method is a winner. I managed to create

a mass of mycelium this fall using oyster mushroom stem butts with nearly no effort.

Still, I've always interested in learning new techniques, and Growing

Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms had a few in depth mushroom

cloning tips.

First of all, it's best

to start with a young mushroom in the button

stage when cloning. Also, I probably should have used only the

inside of the stem butt since the outer portion is likely to be

contaminated with competitor species, especially when cloning

ground-fruiting mushrooms. Other locations on the mushroom are

just as useful for cloning, including the area just above the gills on

the cap and the area on the stem right below the disk of the cap.

This post is part of our Growing Gourmet Mushrooms lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Blue skies and above freezing temperatures helped us to breeze through

two and a half more wall sections of our home

made storage building project today.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

As

we pull together our first semi-serious structure on the farm, we've

received a

lot of feedback from really helpful folks who want us to build

something more sturdy.

Some of the feedback is right on track --- we are new to this after all

and we just miss some steps. For example, we'll be adding a

header to both load-bearing walls to fix the window/door problem and

will add rim joists on the ends of the floor joists.

As

we pull together our first semi-serious structure on the farm, we've

received a

lot of feedback from really helpful folks who want us to build

something more sturdy.

Some of the feedback is right on track --- we are new to this after all

and we just miss some steps. For example, we'll be adding a

header to both load-bearing walls to fix the window/door problem and

will add rim joists on the ends of the floor joists.

On the other hand, we've

intentionally underbuilt some areas rather than following the

conventional wisdom to build a house that'll last two hundred

years. Americans seem to be obsessed with building things to last

centuries --- odd since Europeans have only been on this continent for

a few hundred years. As a nation, we build out of steel and

concrete, then opt to tear it all down twenty years later to build

something bigger and better. The rubble is unusable --- pure

waste. It's almost as if we're struggling to overcome our own

mortality, or to prove ourselves immune to the natural cycle of decay.

When

we visited Mexico,

our tour guide told us that traditional Mayan families tore down their

houses and rebuilt them every few years. The structures were made

of plant matter that could end up back in the garden, so this wasn't

really waste. They also built modularly, making several small

structures instead of one huge house so that when one hut had to be

taken down it didn't turn their lives inside out. Similarly, the

folks who lived on our farm before us believed that a dozen rocks

sitting on the ground were a fine foundation for their house --- and

the structure stood for three quarters of a century. I think all

of these people had a good point --- why not build something simpler

and cheaper that won't last forever and instead plan to repair or

replace in a decade or two?

Granted,

if you live in the city or are paying off a mortgage, you probably have

to build for the long haul and abide by nitpicky building codes,

spending ten times as much money on your house as is actually

necessary. The freedom to do our own thing is one of the many

reasons we love our farm. Sure, some of our experiments will

probably fail, and our building piers may start to rot out in ten or

twenty years. But we've barely put any cash into it, so we can

just rebuild.

Granted,

if you live in the city or are paying off a mortgage, you probably have

to build for the long haul and abide by nitpicky building codes,

spending ten times as much money on your house as is actually

necessary. The freedom to do our own thing is one of the many

reasons we love our farm. Sure, some of our experiments will

probably fail, and our building piers may start to rot out in ten or

twenty years. But we've barely put any cash into it, so we can

just rebuild.

Or maybe we're just

young and stupid. :-) Time will tell....

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

So you've cloned

your mushroom ---

now what? Paul Stamet's Growing

Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms

comes at this from a commercial point of view, so he recommends working

in an

ultra-sterile laboratory and growing cloned mushrooms on agar in

petri dishes. Once the mycelium has nearly colonized the entire

petri dish, he cuts the agar into sections and uses it to inoculate

jars of grain.

So you've cloned

your mushroom ---

now what? Paul Stamet's Growing

Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms

comes at this from a commercial point of view, so he recommends working

in an

ultra-sterile laboratory and growing cloned mushrooms on agar in

petri dishes. Once the mycelium has nearly colonized the entire

petri dish, he cuts the agar into sections and uses it to inoculate

jars of grain.

Although Stamets' lab

technique isn't really applicable on our farm, I

still teased out a lot of information that will probably be equally

true for our cardboard

mushroom cultivation.

The purpose of this stage in the procedure --- known as the spawn run

--- is to take a little bit of fungal growth and turn it into a lot of

growth. Stamets repeatedly urges you to keep the spawn running at

all times by providing the perfect growing conditions --- moderate

humidity of around 60 to 75%, a warm temperature

around 75 degrees Fahrenheit, and darkness to moderate light.

If you play your cards

right, the mycelium will run very quickly at this point and it must

always have more room to grow into. Never let the spawn cover all

of its petri

dish/ cardboard/ whatever or it will use up its food, build up wastes

to

toxic levels, and lose vitality. Once the mycelium comes near the

edge of its container, expand it by mixing the spawn into five to ten

times as much fresh substrate. Feel free to expand your spawn

twice (which means it can become 100 times bigger than it was to start

with!), but use caution when expanding beyond that or your mycelium may

show loss of vigor.

This post is part of our Growing Gourmet Mushrooms lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Today was a great day for laughing and celebrating Anna's mom's

birthday.

One

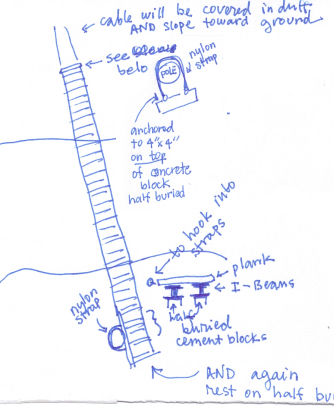

of the least important casualties in the blizzard of '09 was our clothesline.

The wet snow clung to our old cotton line so heavily that three of the

four strings snapped! They were pretty rotten anyway, so rather

than tie yet another knot in them, I opted to replace all four.

One

of the least important casualties in the blizzard of '09 was our clothesline.

The wet snow clung to our old cotton line so heavily that three of the

four strings snapped! They were pretty rotten anyway, so rather

than tie yet another knot in them, I opted to replace all four.

Our barn is a royal

mess, but it has its uses. A few minutes of

poking around turned up a spool of some kind of cable --- plastic over

wire. Perfect clothesline replacement at an unbeatable price!

Once I cut the new line

pieces to the right length and tied them in

place, I started wondering whether that cable should have been saved

for something more important. I hope it wasn't leftover ethernet

cable from Joey's yurt....

Next

week, I'll continue my summary of the techniques Paul Stamets uses to

cultivate mushrooms in a commercial setting. But I wanted to take

a break and talk about my own experiment. If you haven't already,

you can read how I

sandwiched oyster mushroom stem butts

between layers of wet cardboard in a flower pot --- this is the cloning

stage of the operation. After a week, I saw mycelium

running across the cardboard, so I expanded

it by putting the mycelium between more layers of wet cardboard in a

bigger container.

Next

week, I'll continue my summary of the techniques Paul Stamets uses to

cultivate mushrooms in a commercial setting. But I wanted to take

a break and talk about my own experiment. If you haven't already,

you can read how I

sandwiched oyster mushroom stem butts

between layers of wet cardboard in a flower pot --- this is the cloning

stage of the operation. After a week, I saw mycelium

running across the cardboard, so I expanded

it by putting the mycelium between more layers of wet cardboard in a

bigger container.

And then I messed

up. The electricity went out and the trailer's interior

temperature dropped pretty low --- nearly to freezing on the floor

furthest from the wood stove where I happened to have my spawn.

When I checked on it, my mycelium was just sitting there and some of it

had died back. Drat! I'm hoping that the cold temperatures

just put my fungi into temporary hibernation, so I've moved them to a

warmer location and will report back in a few weeks. If I don't

see growth by then, I'll go back to the beginning with new mushrooms in

the spring.

My dream is to develop a

relatively simple method of propagating oyster mushrooms on the home

scale, without petri dishes, autoclaves, or even storebought

grain. Wouldn't it be great if mushroom-keeping was as easy as

building a worm bin and if those mushrooms could be fed with your junk

mail and cardboard, turning waste into food and garden soil? In

case you think I'm living in an ivory tower, check

out this website where the author turned cardboard and junk mail into

mushrooms --- it is

possible! I just need to work a few kinks out of my system.

My dream is to develop a

relatively simple method of propagating oyster mushrooms on the home

scale, without petri dishes, autoclaves, or even storebought

grain. Wouldn't it be great if mushroom-keeping was as easy as

building a worm bin and if those mushrooms could be fed with your junk

mail and cardboard, turning waste into food and garden soil? In

case you think I'm living in an ivory tower, check

out this website where the author turned cardboard and junk mail into

mushrooms --- it is

possible! I just need to work a few kinks out of my system.

This post is part of our Growing Gourmet Mushrooms lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

We got the Chopper

1 axe up and running thanks to a couple of replacement springs

and clips from the Chopper 1 website.

We got the Chopper

1 axe up and running thanks to a couple of replacement springs

and clips from the Chopper 1 website.

I've only just started using it, but I can already say I like it a lot.

It feels like I'm getting more splitting action for less energy input,

which is a very good thing. What I like most so far is the feeling of

increased safety. When there's not enough power to split the log

the Chopper 1 just sort of bounces as opposed to grazing off out of

control like the Super

Splitter has been known to do if your aim is a little off.

Credit goes to Anna for capturing the exact moment when the Chopper 1 is

completing a split.

The temperatures rose above

freezing at last, and the month-old snow began to creep back toward the

hill. The first daffodil leaves peeked through the soil in the

sunniest spot, and an amorous cardinal started to sing.

The temperatures rose above

freezing at last, and the month-old snow began to creep back toward the

hill. The first daffodil leaves peeked through the soil in the

sunniest spot, and an amorous cardinal started to sing.

I celebrated by washing

our laundry, pumping water down the hill from the thousand

gallon tank since our water line is still frozen. Then I

turned off the pump...and water kept right on flowing. Gotta love

capillary action! Now I know that I only need to use electricity

to get the suction started --- after that, water will flow four feet up

out of the tank all by itself!

The frozen water

shuffle got a bit easier after I installed a plastic faucet onto

the pour spout of our 6 gallon jug.

Winter

is the season that makes or breaks bee hives. Our goal is to be

such good bee stewards that our fuzzy little friends have no problem

with the cold weather.

Winter

is the season that makes or breaks bee hives. Our goal is to be

such good bee stewards that our fuzzy little friends have no problem

with the cold weather.

Although the hives look

abandoned during most of the winter, during warm spells we can see the

bees fly out on "cleansing flights" --- this is a euphemism for the

fact that honey bees won't use the bathroom in the hive. Luckily,

bees are able to hold it and only need one warm day a month for their

cleansing flights. While they're out, I've also seen them poking

around on the ground, seeming to lap up water from melting snow.

During the rest of the

winter, the bees huddle together around the queen (and the

honey.) They slowly rotate from the outside to the center so that

no one gets too cold. At the core of this cluster of bees,

workers shiver their bodies and raise the temperature of the cluster as

high as 95 Fahrenheit, but just outside the cluster, the unheated

portion of the hive may drop below freezing.

Our job as winter

beekeepers is quite simple --- make sure that

the bees have enough honey to keep shivering. We took

advantage of a day above 50 on Friday to quickly open up the hives and

count the frames of honey. All three still have good stores,

though one has significantly less than the others. If that hive

is still low on honey during the February check, I'll give them a few

frames of sweet stuff from our strongest hive, which has plenty to

spare.

In doing some research for the home

made storage building I discovered the term garden office which is

how they describe some sheds in parts of Europe.

In doing some research for the home

made storage building I discovered the term garden office which is

how they describe some sheds in parts of Europe.

Shedworking.co

is a great place to browse pictures of other garden offices to spark

your imagination and learn new techniques.

I'm partial to this thatch roof design, but don't think it would work

for us here.

My

sister has been doing a lot of thinking and writing about the impact of

routine in her life, and that got me thinking about my own

routines. The first half hour of my "work day" is always the same

--- walking

Lucy and then taking care of the chickens.

Although I rarely write

about it here, the morning chores are a very important part of the

Walden Effect. They clear my head and give me time to think

through any thorny issues that need my attention.

Saturday, I brought the

new camcorder along to document my journey. I hope you enjoy

seeing a glimpse of my daily life rather than finding it boring --- if

the latter, take heart that the video is less than two minutes long.

Last

week, I posted how to

clone mushrooms then

expand

your spawn as the

first steps toward growing your own mushrooms. Of course, if you

have extra cash and little time, you can always buy spawn from one of

the many companies that cater to the home mushroom grower.

Regardless of how you get it, what do you do with that spawn?

Last

week, I posted how to

clone mushrooms then

expand

your spawn as the

first steps toward growing your own mushrooms. Of course, if you

have extra cash and little time, you can always buy spawn from one of

the many companies that cater to the home mushroom grower.

Regardless of how you get it, what do you do with that spawn?

The pros grow their

mushrooms indoors in bags, trays, or jars. These methods are

definitely the most cost-effective for large-scale growers since the

growing conditions can be tweaked easily to speed up mushroom

production. However, I'm leery of indoors growing since it

requires sterile conditons and lots of up front equipment costs.

Basically, by providing the perfect conditions for your mushrooms,

you're also providing the perfect conditions for lots of molds and

bacteria, so you need to fight contaminants constantly.

On the homestead scale,

I think that outdoor growing is usually the best way to go. We've

had good luck growing both

oyster mushrooms and shiitakes on logs, and a similar method can be

used to inoculate fresh stumps.

A new method I want to

check out is growing mushrooms in beds of wood chips, straw, or other

materials. If you inoculate your chips in early spring or fall,

the mycelium will naturally expand through the substrate and you may

get mushrooms within the same year. Just be sure to give the

fungus at least four weeks to grow before cold weather kicks in and put

your mushroom bed in a damp, shady, north-facing area.

This post is part of our Growing Gourmet Mushrooms lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

We closed in on finishing up the walls for the do it

yourself storage bulding today. It was such a treat to have the sun

on our backs during the afternoon portion of the project.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

This video started out as a

serious summary of Monday morning's work on the homemade

storage building.

Then I sped it up so you wouldn't be sitting around waiting for

something to happen. And suddenly the chipmunk noises made me

laugh.

Mark watched it and said

something along the lines of, "That's nice, dear." I think I may just have an

odd sense of humor.... Hope at least a few of you

get a kick out of it.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

The material which mushrooms are grown on

is known as the substrate. Although some species are very picky,

others (like the oyster mushroom) can be grown on almost anything that

started life as a plant. We'll provide sterilization instructions

for all of these substrates tomorrow. For now, here are recipes

for turning your plant matter into growing media.

The material which mushrooms are grown on

is known as the substrate. Although some species are very picky,

others (like the oyster mushroom) can be grown on almost anything that

started life as a plant. We'll provide sterilization instructions

for all of these substrates tomorrow. For now, here are recipes

for turning your plant matter into growing media.

When commercial growers start their mycelium in a petri dish, they

often expand it into jars of sterilized grain. Millet, rye, and

wheat are most often used, but Paul Stamets reports that any grain will

do. To fill a one quart jar, mix 200 grams of grain, 220 mL of

water, and 1 gram of gypsum (to keep the kernels separated and provide

calcium and sulfur.)

Later, mycelia can be expanded onto a mixed wood substrate made up of

different sizes of chips and sawdust. The fungus will quickly

colonize the smallest sawdust grains, while the larger chips provide

for air flow and allow the fungus to form rhizomorphs that lead to big

mushroms. Paul Stamets recommends using only one species of tree

at a time, if possible, and sticking to fast-growing and -decomposing

species like alder. These trees have more sapwood, which is easy

for your mycelium to colonize quickly. His recipe for sawdust

spawn is very simple --- moisten the sawdust to 60 to 70% water,

sterilize, and innoculate.

Sawdust and wood chips are a bit hard for

your mushrooms to digest quickly, so if you want to boost your yields

you may choose to supplement them with some source of protein.

Lots of homestead and farm waste products fit the bill, including rice,

wheat, or oat bran; ground corn; grape pumice from wineries; spent

barley from breweries; vegetable oil; and stale bread. Enriching

your substrate, though, is a double-edged sword --- the extra nutrients

also help contaminants grow quickly, so you'll need to double your

sterilization time. Paul Stamets' recipe for enriched sawdust is

as follows: 100 pounds of sawdust, 50 pounds of one half to four inch

wood chips, 40 pounds of bran, and 5 to 7 pounds of gypsum, moistened

to 60 to 65% water and then sterilized.

Sawdust and wood chips are a bit hard for

your mushrooms to digest quickly, so if you want to boost your yields

you may choose to supplement them with some source of protein.

Lots of homestead and farm waste products fit the bill, including rice,

wheat, or oat bran; ground corn; grape pumice from wineries; spent

barley from breweries; vegetable oil; and stale bread. Enriching

your substrate, though, is a double-edged sword --- the extra nutrients

also help contaminants grow quickly, so you'll need to double your

sterilization time. Paul Stamets' recipe for enriched sawdust is

as follows: 100 pounds of sawdust, 50 pounds of one half to four inch

wood chips, 40 pounds of bran, and 5 to 7 pounds of gypsum, moistened

to 60 to 65% water and then sterilized.

The last widely used mushroom substrate is straw --- this is Paul

Stamets' favorite for economical oyster mushroom production. He

chops wheat, rye, oat, or rice straw into 1 to 4 inch lengths, then

pasteurizes it and inoculates.

Although grain, wood chips, and straw are the main substrates used in

commercial mushroom production, you shouldn't stop there! Growing Gourmet and Medicinal

Mushrooms teased me with notes that mushrooms can be grown on

newspaper, cardboard, books, corncobs, corntalks, peanut shells, tea

leaves, coffee grounds, and much more. I hope that by this time

next year I'll have information on the best ways to turn these waste

products into mushrooms!

This post is part of our Growing Gourmet Mushrooms lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Today we installed some hard wood beams from the old house on the top

of our walls to form a solid box for the storage

buiding. We decided to extend each side out by a foot to provide

some additional cover for the outer walls.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

Just keeping the farm going uses most

of our energy, but we like to end each year a little better off than

the last. I get easily frustrated, though, when the big projects

have to get pushed to the back burner to accomodate planting, weeding,

and the usual cycle of farm chores. The solution? Take the

dozens of big projects we'd like to complete and narrow them down to

the top ten to be completed each year.

Just keeping the farm going uses most

of our energy, but we like to end each year a little better off than

the last. I get easily frustrated, though, when the big projects

have to get pushed to the back burner to accomodate planting, weeding,

and the usual cycle of farm chores. The solution? Take the

dozens of big projects we'd like to complete and narrow them down to

the top ten to be completed each year.

I thought you might

enjoy seeing last year's top ten goals (and our status on each

project). This is my version of New Year's resolutions

--- why make a resolution when you can instead make a plan?

Better

steps to the house. We shored up the existing steps and

they work fine.

Better

steps to the house. We shored up the existing steps and

they work fine.- Fence deer out of the full perimeter. After some fencing, Mark invented our deer deterrent, which solved the same problem for vastly smaller amounts of time and money.

- Start saving for retirement (again.) This goal fell by the wayside for a few years as we poured our finances into the farm's startup costs. Luckily, this year we got back on track and started putting money away again. (Check out our ebook for information about becoming fiscally solvent on the farm.)

- Running water in the trailer. We came close to reaching this goal, burying about 75% of the water line from the thousand gallon tank to the trailer. We've still got a bit more to go, though, which is why our lines froze up and we went back to carrying water.

Bees.

We started our bees!

Bees.

We started our bees!- Irrigation to all plants. Due to an extremely wet summer, we didn't water much at all. But we did put in most of the irrigation infrastructure we'll need. We'll test it out during the next drought.

- Expand the shiitakes. We not only added a few more shiitake logs, we even started oyster mushrooms (which fruited already!)

Root

cellar. After embarking on a huge root cellar project, we

changed directions and decided

to work on making

a root cellar out of a fridge. We completed it, but the dirt

slumped in a rain and pushed the fridge over. We need to dig it

out and add a roof.

Root

cellar. After embarking on a huge root cellar project, we

changed directions and decided

to work on making

a root cellar out of a fridge. We completed it, but the dirt

slumped in a rain and pushed the fridge over. We need to dig it

out and add a roof.- Fix the barn roof. We didn't get to this....

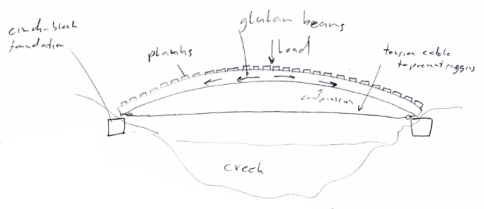

- Build a wider, higher footbridge. We shored up the existing bridge instead, but it gave out in early winter.

- Build a woodshed. Done!

- Build Mark a loft/office space. We built him a loft inside the trailer, then made a good start on our new building.

As you can see, we didn't manage to narrow our goals down to ten, but

we did complete seven and make good progress on another four. Not

too bad for working around all of the little things that inevitably

come up on a farm! Stay tuned for this year's overly ambitious

goals in a later post.

When

growing mushrooms, your goal is to get your mycelium to colonize a new

substrate as quickly as possible --- definitely within two weeks.

As every gardener knows, nature abhors a vaccuum. Just as your

garden beds will quickly become coated with weeds if you don't plant

your veggies thickly or mulch them, your mushroom substrate will be

full of harmful contaminants if you don't make sure your mushrooms get

a head start.

When

growing mushrooms, your goal is to get your mycelium to colonize a new

substrate as quickly as possible --- definitely within two weeks.

As every gardener knows, nature abhors a vaccuum. Just as your

garden beds will quickly become coated with weeds if you don't plant

your veggies thickly or mulch them, your mushroom substrate will be

full of harmful contaminants if you don't make sure your mushrooms get

a head start.

The best way to

jump-start your mycelium in a new substrate is to

sterilize or pasteurize the material to kill off the harmful

competitors. Heat is the primary method used, but you have to be

sure not to raise the temperature of your substrate over 200 F or

you'll do more harm than good by waking up bad molds.

Sterilization sounded

very difficult to me until I realized that the methods

used at the home scale are basically the same as canning. Want to