archives for 10/2009

Picking Rhubarb Swiss

Chard on a chilly morning, I nearly put my hand into a stunning

dragonfly. The insect was too cold to fly away immediately so it

just quivered its wings as I snapped shot after shot. Finally,

its muscles were warm enough for liftoff, and the dragonfly sped off to

nibble on gnats.

I suspect our healthy population of dragonflies (and bats) is part of

the reason why we aren't plagued by biting insects, despite living next

door to a swamp. If you want dragonflies in your garden (and you

do!), putting in even a tiny pond can do the trick, especially if you

add some plants to give the dragonflies a spot to land. As a kid,

I transplanted some dragonfly nymphs from a more established pond to my

tiny backyard water garden and was rewarded with a healthy dragonfly

population for the rest of my childhood.

My dragonfly is a female Common

Green Darner, distinguished from the male by the brown eyes.

Even if you don't care about dragonfly identification, you should check

out the site linked above for the stunning photos. Enjoy!

Some of your storage

vegetables need to be cured before storage; some don't. If you

cure vegetables that don't need to be cured, they'll rot. And if

you don't cure vegetables that do need to be cured, they'll rot

too. Time for a good list!

| Vegetable |

Curing

method |

| Beet |

none |

| Cabbage |

none |

| Carrot |

none |

| Garlic |

1 - 2 weeks in a warm, dry place |

| Onion |

2 - 3 weeks in a warm, dry place |

| Parsnip |

none |

| Potato |

2 weeks at 50 - 60 degrees

Fahrenheit and 95% humidity (slightly warmer than a root cellar) |

| Sweet Potato |

2 weeks at 80 - 85 degrees

Fahrenheit (dry) |

| Turnip |

none |

| Winter Squash (including

Pumpkins) |

2 weeks in a warm, dry

place. (Don't cure acorn squash!) |

Curing serves a couple of purposes. In all crops except white potatoes, a primary purpose is to dry the vegetable up so that it won't rot in storage. White and sweet potatoes and winter squashes develop a hard skin during curing that will protect the crop during storage.

The cheapest and easiest method I've come up

with for curing vegetables is to lay them out on some old window

screens Mom found for me by the side of the road. I put the first

screen on four cinderblocks, cover the screen with drying vegetables,

then put bricks on the four corners of the frame to let me put another

screen on top for a second drying layer. The trick is to get good

air circulation all the way around your vegetables, so don't pile the

roots on top of each other. If you're a good scavenger, you can

recreate my curing rack setup for next to nothing.

The cheapest and easiest method I've come up

with for curing vegetables is to lay them out on some old window

screens Mom found for me by the side of the road. I put the first

screen on four cinderblocks, cover the screen with drying vegetables,

then put bricks on the four corners of the frame to let me put another

screen on top for a second drying layer. The trick is to get good

air circulation all the way around your vegetables, so don't pile the

roots on top of each other. If you're a good scavenger, you can

recreate my curing rack setup for next to nothing.People with more space will get away with drying their vegetables inside, but our trailer just isn't big enough to handle that type of operation. Instead, I harvest my crops a bit earlier than other folks might and put my drying racks under a tarp or roof outside to cure storage vegetables before the frost hits.

| This post is part of our Storage Vegetables lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We started putting the foundation together for our upcoming 8x16

workshop/bath house today.

The ground needs to be built up in a few places and pounding it with

the back of the new shovel seems to do the trick nicely.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

Wednesday night reached

a low of 37 F --- dangerously close to the frost. We're not ready

to light our first fire, so it took a while for us to emerge from our

nightly cocoons. When I did get up, Strider was unusually

affectionate, nestling down beside me as I read my morning blogs, and

even Lucy didn't seem quite so keen on uncurling herself before her

morning walk.

The great thing about sudden cold weather, though, is wildlife.

"Cold-blooded" animals aren't ready to hibernate yet, but the chilly

temperatures make them slow down. While weeding, I got a great

shot of a tiny Pickerel Frog. Usually, Pickerel Frogs are the

fastest amphibians on our farm, pushing off with those long hind legs

and disappearing before my mind even registers "frog." But not

today!

The

trick to keeping your storage vegetables fresh all winter is

understanding the type of conditions they prefer. Storage

conditions can be measured by temperature, humidity, ventilation, and

darkness. Nearly all crops like it dark and airy, but each

vegetable has a favorite range of temperature and humidity conditions.

The

trick to keeping your storage vegetables fresh all winter is

understanding the type of conditions they prefer. Storage

conditions can be measured by temperature, humidity, ventilation, and

darkness. Nearly all crops like it dark and airy, but each

vegetable has a favorite range of temperature and humidity conditions.

In practice, I divide

our storers up into two main categories --- cool, wet storers and warm,

dry storers. Cool, wet storers thrive in root cellars and can

also be kept well in simpler storage operations like mulched garden

rows, storage mounds ("clamps"), trenches, a basement, or the crisper

drawer in your fridge. Warm, dry storers will do much better in

your attic, an unheated room, or under your kitchen sink.

I'm vastly

oversimplifying by dividing crops into these two categories, but it's

far too easy to get carried away trying to provide a half dozen

different storage conditions to keep all of your crops happy. The

table below gives some storage data on common vegetables:

| Vegetable |

Optimal

storage conditions |

My storage

conditions |

My storage

location |

| Beet |

32 - 40 F, 90 - 95% humidity | cool, moist |

haven't done it yet |

| Cabbage |

32 - 40 F, 80 - 90% humidity | cool, moist |

haven't done it yet |

| Carrot |

32 - 40 F, 90 - 95% humidity |

cool, moist |

haven't done it yet |

| Garlic |

32 - 50 F, 60 - 70% humidity | warm, dry |

kitchen shelf |

| Onion |

32 - 50 F, 60 - 70% humidity | warm, dry |

kitchen shelf |

| Parsnip |

32 - 40 F, 90 - 95% humidity | cool, moist |

haven't done it yet |

| Potato |

32 - 40 F, 80 - 90% humidity | cool, moist |

storage mound |

| Sweet Potato |

50 - 60 F, 60 - 70% humidity |

warm, dry |

under the kitchen sink |

| Turnip |

32 - 40 F, 90 - 95% humidity | cool, moist |

haven't done it yet |

| Winter Squash (including Pumpkin) |

50 - 60 F, 60 - 70% humidity | warm, dry |

under the kitchen sink |

Despite ignoring some of the optimal conditions, I've had great luck keeping onions, winter squash, and sweet potatoes fresh until they're all eaten up. (In fact, we still have some of last year's sweet potatoes to finish up as this year's are curing!) Don't get too caught up in thinking you have to build a fancy root cellar before you can enter the world of storage vegetables.

| This post is part of our Storage Vegetables lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Boing

Boing has an interesting post on a National Geographic news article

that reports on a recent round of tests to see how productive a mix of

human urine and wood ash would be for tomatoes.

Boing

Boing has an interesting post on a National Geographic news article

that reports on a recent round of tests to see how productive a mix of

human urine and wood ash would be for tomatoes.

The plants fertilized this way yielded 4 times as much fruit as non

fertilized plants, and bore a significant increase in the nutrient

magnesium.

I would be a little concerned about the long term salt build up that

may occur with this method and need more information before I try

something as risky as mixing a salty substance with our topsoil.

Flowers tend to be at the very bottom of my

gardening list, and I only managed to toss some seeds in the ground

around June this year. I ignored them for a month, then gave them

a half-hearted weed. Flowers. Whatever.

Flowers tend to be at the very bottom of my

gardening list, and I only managed to toss some seeds in the ground

around June this year. I ignored them for a month, then gave them

a half-hearted weed. Flowers. Whatever.

But in the middle of September, the first brilliantly red zinnia popped

open. Our deer deterrents

were up and running, so a couple of sunflowers kept their leaves,

opening huge yellow heads. The Cocks' Comb from Mark's mom pushed

up brilliant magenta combs and the marigolds turned into a hedge of

orange.

Suddenly, my half-hearted flower bed is the heart of the garden.

Why didn't I plant more? Why didn't I plant them sooner? I

guess next year I'll have to pay more attention to flowers!

We checked up on our remaining 3 bee hives

today and were happy to discover evidence of well functioning

colonies in all of them.

We checked up on our remaining 3 bee hives

today and were happy to discover evidence of well functioning

colonies in all of them.

The home made frame

perch tool seems to have warped a bit since the last upgrade,

which means I should have allowed more distance between the arms.

An easy fix once I finish fixing a few other things around here.

One volunteer, though, is going strong. Its big, red tommy-toes are ripening just about as fast as Lucy can pick them (darn dog!) and the leaves and stem show no sign of blight. Looks like we found a seriously blight-resistant tomato!

I stole one tommy-toe out from under Lucy's nose and am processing the seeds in preparation to saving them for next year. There's a good chance the tomato is Crazy, a variety I grew in my garden last year but that didn't make it onto my roster this year due to old seeds. What didn't kill us will make us stronger!

We started to have some trouble back in the

summer with one of the Plymouth Rock hens laying her egg on the ground, which

made it easy to miss and pull the tractor over it, creating a

scrambled egg in the yard.

We started to have some trouble back in the

summer with one of the Plymouth Rock hens laying her egg on the ground, which

made it easy to miss and pull the tractor over it, creating a

scrambled egg in the yard.

It seems like a golf ball is close enough to an egg to fool even our

smart Plymouth Rocks. No broken eggs since we installed the fake at a

price well under a buck depending on where you get your sporting

supplies from.

When I was in high school, I was obsessed with

water gardening. My father and I built a little concrete pond in

the backyard and I stocked it with plants and aquatic life. But

the places where the concrete liner rose above the surface were an

eyesore, so I did everything I could think of to try to get moss to

grow there. I had absolutely no luck. In the end, I decided

that moss was hard to grow.

When I was in high school, I was obsessed with

water gardening. My father and I built a little concrete pond in

the backyard and I stocked it with plants and aquatic life. But

the places where the concrete liner rose above the surface were an

eyesore, so I did everything I could think of to try to get moss to

grow there. I had absolutely no luck. In the end, I decided

that moss was hard to grow.

Looks like my raised beds don't think so. After our six months of

autumn, one bed has grown quite a nice crop of moss amid the Egyptian

onions. I hope that means that my no-till technique has built an

equally lush soil ecosystem below the surface!

A week from today, Mark and I will be

climbing the Uxmal pyramid on the Yucatan Peninsula. So this

week's lunchtime series is actually a two week series, spanning the

days we'll be away on our honeymoon.

A week from today, Mark and I will be

climbing the Uxmal pyramid on the Yucatan Peninsula. So this

week's lunchtime series is actually a two week series, spanning the

days we'll be away on our honeymoon.

Luckily, I found just

the book to fuel two weeks of permaculture musings: Designing

and Maintaining Your Edible Landscape Naturally by Robert Kourik. This

book was written about the time I entered third grade, but the facts

are nowhere near out of date. Actually, I can see where the

fascinating forest

garden book I read a

few months ago grew organically out of the rich compost of Robert

Kourik's guide.

Robert Kourik's

flawlessly researched and referenced book is also based on his years as

a landscape architect, tempting clients to include edible plants in

their ornamental gardens. This week's first half of the series

sums up his wisdom about the foundation of permaculture plantings ---

soil.

This post is part of our lunchtime series reviewing Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining your

Edible Landscape Naturally.

Read all of the entries:

|

I found out today that our Maytag wringer washer is the model E2L, the

longest running production of any of the wringer machines. The run

started in 1945 and the last one was made in 1983.

Judging by how brittle our discharge hose was I'm guessing ours is

closer to the 1945 era. I tried building one back from scrap pieces and

2 layers of silicone. Tomorrow will be the test run to see if this

operation is a viable solution without any leaking.

I figure chances are pretty good that we'll

return from our honeymoon to a frosted farm, so we're doing frost

preparations before we leave. I've gathered up our curing

sweet potatoes, garlic, and butternut squash to be hung in mesh

bags in the kitchen. In the garden, I picked the last of the

basil (already nipped by a 35 degree night on Saturday) and what may be

the last of the summer squash, peppers, and green beans. One more

gallon of summer bounty hit the freezer and we ate our last batch of

pesto pasta with basil fresh from the sun.

I figure chances are pretty good that we'll

return from our honeymoon to a frosted farm, so we're doing frost

preparations before we leave. I've gathered up our curing

sweet potatoes, garlic, and butternut squash to be hung in mesh

bags in the kitchen. In the garden, I picked the last of the

basil (already nipped by a 35 degree night on Saturday) and what may be

the last of the summer squash, peppers, and green beans. One more

gallon of summer bounty hit the freezer and we ate our last batch of

pesto pasta with basil fresh from the sun.

I'm torn about whether to pick all of the green peppers and bring them

inside to eat when we return, or whether to gamble by draping the

plants in row covers and hoping that we'll have some orange peppers

when we get back instead. I vastly prefer the latter, but think I

might do the former --- I'm not big on gambling and even green peppers

taste pretty good after the frost.

I've been dabbling in no-till techniques for

the last few years, due to a vague understanding that tilling is bad

for the soil. Robert Kourik's book gave me the low down on the

best no-till techniques and why they succeed (or fail.)

I've been dabbling in no-till techniques for

the last few years, due to a vague understanding that tilling is bad

for the soil. Robert Kourik's book gave me the low down on the

best no-till techniques and why they succeed (or fail.)

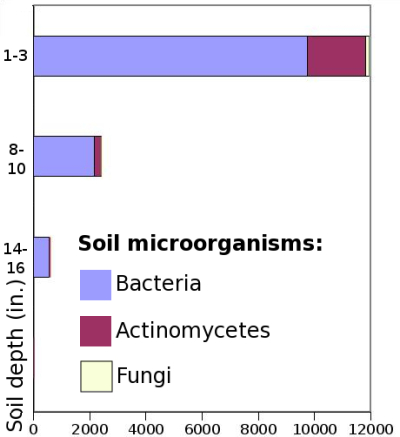

So, what's wrong with

tilling? Although we can't see it, our soil is teeming with

microscopic and macroscopic life, most of which lives in the top three

inches of soil. Tilling churns up soil, mixing the microorganism

playground with the lower soil and resulting in a lot less life.

Although you might expect that the microorganisms folded deeper into

the earth just expand their populations, lack of air and sun quickly

kills them off.

Bare soil is another

bane of conventional tilling. Erosion is the obvious problem ---

rain washes away the precious topsoil when it is unprotected by plants

or mulch. But sun is just as much of a problem. When bare

soil is exposed to summer sun, the heat vaporizes nitrogen and kills

the precious soil microorganisms, resulting in a garden that requires

much more fertilizer in order to grow your veggies.

Of course, we can't just

throw our lettuce seeds amid the grass in our lawns and expect it to

grow. So how do we garden without annual tilling and bare soil?

This post is part of our lunchtime series reviewing Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining your

Edible Landscape Naturally.

Read all of the entries:

|

The wringer

washer is working again with a small leak, which is a bit smaller

than before.

The wringer

washer is working again with a small leak, which is a bit smaller

than before.

I think silicone was a bad choice for this problem due to the nature of

the metal in question, but I went for it because it's what I had on

hand.

Next time I think I'll take john wilson's advice and use some of that

fiberglass bondo stuff when trying to merge this type of metal with a

hard plastic.

Conventional wisdom has

it that honeybees are attracted to asters and goldenrod at this time of

year. The chilly, cloudy weather we've had lately hasn't been

conducive to much bee activity at all, but when the sun does tempt our

bees out, they go straight to the smartweed instead. Tiny, pink

smartweed flowers seem to be just my bees' speed, especially since the

"lawn" right outside their hive is chock full of it.

I have a difficult time identifying smartweeds. All of them

belong to the genus Polygonum,

half of them are invasive species, and most areas have about two dozen

look-alike species to choose from. My best guess is that my

smartweed is Oriental Lady's Thumb (Polygonum

caespitosum), a native of Asia that is common in damp areas.

Mark suggested collecting seeds of the smartweed and expanding its

territory since the flowers seem to be so popular with the bees.

I'm not comfortable encouraging invasive plants too much, but I think I

will make a habit of skipping the last grass mowing in the fall to give

our bees some late nectar right by the hive.

I've already written a long post about sheet mulching, one good method of growing

plants without tilling the soil. The problem with sheet mulching

is that it requires gobs of organic matter. Can you get similar

results with less outlay of cash?

I've already written a long post about sheet mulching, one good method of growing

plants without tilling the soil. The problem with sheet mulching

is that it requires gobs of organic matter. Can you get similar

results with less outlay of cash?

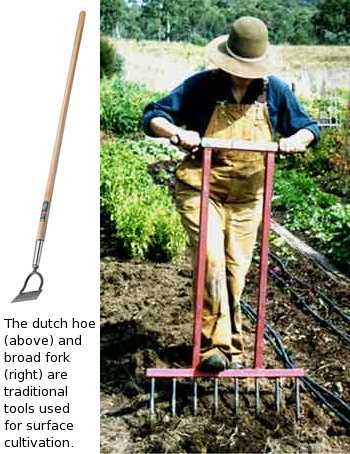

A traditional British

method of gardening without tilling is known as surface

cultivation. Farmers usually till or dig the soil the first year

to loosen the ground and increase soil pores, but after this they

merely layer two to four inches of compost onto the ground each year

and plant without tilling. A special hoe known as a Dutch hoe

cuts off weeds just below the crown, leaving the roots in place to

increase fertility of the soil and leaving the tops in place to mulch

the soil surface. By the third year of surface cultivation, very

few weeds are left since new seeds aren't turned up through tilling.

My gardening technique

has aspects of surface cultivation in it, and I'm looking forward to

that decline in weeding (two years from now since my 2008 garden went

to seed and set me back a couple of years.) Robert Kourik notes

that the tedious weeding in surface cultivation can be minimized by

mulching as much as possible. My father has good luck laying damp

newspapers around his vegetables, a method that I may have to try next

year. This year's grass

clipping mulch has

also been highly effective.

The problem with surface

cultivation, beyond labor-intensive weeding, is that productivity often

begins to decline after 5 to 6 years when soil compacts. Some

farmers simply till their garden at that point and begin again.

Others use a spading fork or broad fork to loosen the soil without

tilling. I suspect that simple crop rotation may do the trick in

our garden --- we grow enough root crops that require the ground to be

churned up during harvest that we will probably end up digging every

bed at least once or twice a decade.

This post is part of our lunchtime series reviewing Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining your

Edible Landscape Naturally.

Read all of the entries:

|

Transporting piles of leaf material with a large tarp

is a lot easier than putting them in trash bags if your goal is garden

mulch.

September

gave us 6.2 inches of rain over 10 days. The days that didn't

rain were generally cloudy, so I put off doing laundry until we both

ran out of the essentials.

September

gave us 6.2 inches of rain over 10 days. The days that didn't

rain were generally cloudy, so I put off doing laundry until we both

ran out of the essentials.

Tuesday, I gave in and washed anyway. Three big loads of laundry

later, I had filled up the clothesline and moved on to draping clothes

on the grape trellises. I didn't even get to our bedding before

running out of both laundry detergent and space on the line.

Four hours of clouds later, it started to rain. I scurried around

and gathered up damp clothes, then draped them all over the house while

a quarter inch of water fell on our garden. Wednesday turned out

to be the prettiest sunny day in a long time, so I carried all of the

clothes back outside,

flipping clothes over halfway through the day so that every one finally

dried all the way through. Just this once, I think if I had a

clothes drier I would have used it. (Good thing I don't have one!)

Despite the astonishing amount of effort required to get there, we have

enough clean clothes to last us for our entire week long

honeymoon. Most of the posts for the next eight days will be

auto-posted --- saved up topics we never got a chance to serenade you

with during the height of the growing season. The farm will be in

the able hands of my brother, and we plan to not even check email for

most of the time. So if anything looks funny on the site, I

promise I'll fix it when I get home!

Another no-till technique is double-digging, a

slightly complicated method of breaking up the soil to a depth of two

feet without inverting the soil layers. Double-digging is

extremely laborious, but can result in porous soil that greatly

increases vegetable yields, especially in heavy clay soil like

ours. After double-digging, soil doesn't need to be worked for

several years, much like the surface cultivation system.

Another no-till technique is double-digging, a

slightly complicated method of breaking up the soil to a depth of two

feet without inverting the soil layers. Double-digging is

extremely laborious, but can result in porous soil that greatly

increases vegetable yields, especially in heavy clay soil like

ours. After double-digging, soil doesn't need to be worked for

several years, much like the surface cultivation system.

We used a modified method of double-digging to create

our raised beds. First, Mark tilled up our topsoil, being

careful not to go too deep (not a problem with the tiny tiller I had

him working with the first year.) Then I laid out aisles and

shoveled the loose soil from the aisles to the side to create raised

beds. The result is a double thickness of loose topsoil without

as much of the back-breaking labor of double-digging. The

grassy/clovery aisles between our raised beds produce high quality

mulch, protect the soil from erosion, and promote water infiltration

(rather than runoff) during heavy rains.

We used a modified method of double-digging to create

our raised beds. First, Mark tilled up our topsoil, being

careful not to go too deep (not a problem with the tiny tiller I had

him working with the first year.) Then I laid out aisles and

shoveled the loose soil from the aisles to the side to create raised

beds. The result is a double thickness of loose topsoil without

as much of the back-breaking labor of double-digging. The

grassy/clovery aisles between our raised beds produce high quality

mulch, protect the soil from erosion, and promote water infiltration

(rather than runoff) during heavy rains.

After the first

year, we put the rototiller away and spend the rest of our time

weeding, applying manure, and mulching. I'd recommend our bed system

to anyone, with just one caveat. Raised beds don't work well in

sandy soil or extremely hot climates where the soil will dry out

rapidly. Of course, if you have sandy soil, increasing soil

porosity won't be a problem for you anyway.

This post is part of our lunchtime series reviewing Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining your

Edible Landscape Naturally.

Read all of the entries:

|

I was struck by a throwaway sentence in Good Farmers, a book about traditional

farming practices in Central America and Mexico. The author

noted that traditional farmers usually lack heavy equipment and funds

to pay for lots of hired help, so they have to take a process-oriented

approach to big tasks rather than being project-oriented. For

example, if they have a steep hillside that they'd like to terrace and

create farmable ground, traditional farmers are more likely to put in a

spare afternoon here and there building the terrace bit by bit rather

than renting a bulldozer to get 'r done.

I was struck by a throwaway sentence in Good Farmers, a book about traditional

farming practices in Central America and Mexico. The author

noted that traditional farmers usually lack heavy equipment and funds

to pay for lots of hired help, so they have to take a process-oriented

approach to big tasks rather than being project-oriented. For

example, if they have a steep hillside that they'd like to terrace and

create farmable ground, traditional farmers are more likely to put in a

spare afternoon here and there building the terrace bit by bit rather

than renting a bulldozer to get 'r done.

Homesteading is slowly teaching me to slip out of my project-oriented

mindset and enjoy the journey. For example, the wood we bought

was delivered to our parking area, half a mile from our house. At

first, I was considering just taking a day and making golf cart trip

after golf cart trip to bring the wood back to its shed. But

instead I've been taking in a load of wood whenever I need to drive the

golf cart out to the cars anyway. A week later, our shed is

already a third of the way full!

Honeymoon, day 1. We drove south out of

the mountains of Virginia all the way down to the flatlands of

Alabama. Roadside pine trees push their way in amid the hardwoods

I'm used to and an unfamiliar grass coats the edge of the

blacktop. We don't stop for me to botanize, although we do pass a

man pulled off on the side of a six lane highway by a lake, fishing

pole in hand.

Honeymoon, day 1. We drove south out of

the mountains of Virginia all the way down to the flatlands of

Alabama. Roadside pine trees push their way in amid the hardwoods

I'm used to and an unfamiliar grass coats the edge of the

blacktop. We don't stop for me to botanize, although we do pass a

man pulled off on the side of a six lane highway by a lake, fishing

pole in hand.

Down south, the humidity has not yet lifted to give way to a crisp,

mountain fall. I'm a homebody most of the time, but I love the

feeling of covering new territory, even if it is pavement and

buildings. Mark and I sleep fitfully and wake up early, in a

different time zone, ready to explore a Native American mound!

(Nothing photogenic yet on our trip, so this is a picture of the lemon

tree soon after we brought it inside to prepare for our trip.

Huckleberry enjoyed the new addition to his living space.)

The obvious method to prevent bare soil in

a vegetable garden is mulch, but unless you shell out the cash for a

dumptruck load or two, chances are there won't be enough to go

around. How else can you protect your soil?

The obvious method to prevent bare soil in

a vegetable garden is mulch, but unless you shell out the cash for a

dumptruck load or two, chances are there won't be enough to go

around. How else can you protect your soil?

Close plant spacing can shade your soil surface, preventing damage to

the underground ecosystem while also keeping weeds from growing.

I often plant my lettuce and leafy greens far closer than the

instructions on the seed packet recommend. The result is an

endless carpet of green food, with little weeding after the vegetable

seedlings catch hold.

|

|

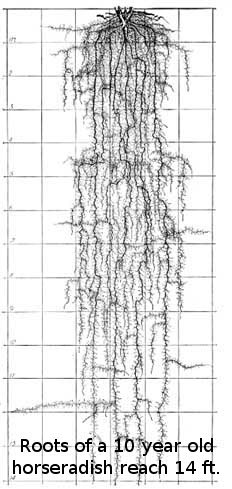

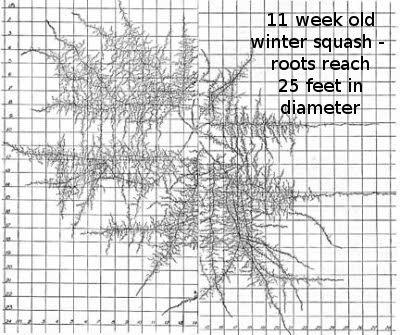

Close spacing does have its limits, though. I've learned the hard way that tomatoes need lots of air circulation in our climate to prevent blight --- Kourik recommends planting them four feet apart. In addition, roots of our garden vegetables are much larger than I'd ever suspected --- carrot and swiss chard roots reach seven feet deep while pumpkin roots can grow horizontally to 20 feet in diameter. Without double digging and heavy amendments of compost, roots of these plants will compete with the neighbors and both will struggle. Check out the amazing root diagrams in John Weaver's Root Development of Field Crops (available free online) for more information. |

More fascinating tidbits from

Robert Kourik's book are coming next week. If you can't wait,

check out his

blog.

This post is part of our lunchtime series reviewing Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining your

Edible Landscape Naturally.

Read all of the entries:

|

Moundsville is an exciting and interactive park that provides an

interesting glimpse into what life may have been like in this country

before European influences began their crusade against all who opposed

them.

This post is part of our Moundville and Cruise to Mexico honeymoon

series.

Read all of the entries:

|

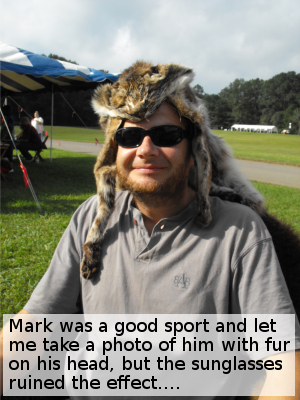

Eight hundred years ago, Moundville, Alabama, was the home of a city of 10,000 people.

Once a year, a thousand of their descendants and random tourists

descend on the mounds for a day of fun and edification. Mark and

I were thrilled to discover that the Native American Festival was being

held the day before our cruise ship departed, and was nearly on our

way. The stars were aligned to bring us to another Native

American mound.

Eight hundred years ago, Moundville, Alabama, was the home of a city of 10,000 people.

Once a year, a thousand of their descendants and random tourists

descend on the mounds for a day of fun and edification. Mark and

I were thrilled to discover that the Native American Festival was being

held the day before our cruise ship departed, and was nearly on our

way. The stars were aligned to bring us to another Native

American mound.

While our visit to Moundville wasn't the same soul-bending experience as our trip to Serpent Mound,

we still ended up rivetted. The mounds themselves were amazing

--- a dozen "small" ones and one sixty feet tall, the last of which we

were allowed to climb. But what really captured my attention was

the educational booths set up for the festival. I learned so much

about Native American crafts that I'll have to turn it into a lunchtime

series --- fire making, river cane baskets, pit-fired pottery!

Then there was the semi-authentic Native American food, an actual

archaeological dig, and an astonishing number of vendors whose crafts

should have been in a museum. Despite hundreds of screaming kids,

we stayed until the Alabama heat sent us scurrying for cover. If

you're ever close to Alabama in October, I highly recommend that you

drop by the festival!

This post is part of our Moundville and Cruise to Mexico honeymoon

series.

Read all of the entries:

|

The location we chose for the new

building has a bit of a slope to it. This requires different size

blocks at different intervals to make it all level.

The location we chose for the new

building has a bit of a slope to it. This requires different size

blocks at different intervals to make it all level.

After a shopping spree at the hardware store I learned you can get the

solid cinder blocks in both 4 inch and 2 inch sizes, which oddly cost

the same even though you get twice as much material with the 4 inch

version.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

During the last frantic day before our

wedding celebration, I noticed a monarch licking the handles of our

iced tea jugs. One of the butterfly's wings was slightly

crumpled, and I guessed that the insect was having trouble making the

long journey to its wintering grounds in central Mexico. Even

though I believe that nature picks off wounded animals for a reason, I

had to carry the monarch over to the sunflowers, where it began feeding

greedily.

During the last frantic day before our

wedding celebration, I noticed a monarch licking the handles of our

iced tea jugs. One of the butterfly's wings was slightly

crumpled, and I guessed that the insect was having trouble making the

long journey to its wintering grounds in central Mexico. Even

though I believe that nature picks off wounded animals for a reason, I

had to carry the monarch over to the sunflowers, where it began feeding

greedily.

Since we're currently cruising toward Mexico

at this moment while my brother watches the farm, I thought this

monarch was an apt symbol of this week's mini-adventure. Despite

being a homebody, I've always dreamed of traveling. Nine years

ago, I did --- setting off with a backpack full of camping supplies and

sketchbooks for a year-long expedition through Great Britain,

Australia, and Costa Rica.

Since we're currently cruising toward Mexico

at this moment while my brother watches the farm, I thought this

monarch was an apt symbol of this week's mini-adventure. Despite

being a homebody, I've always dreamed of traveling. Nine years

ago, I did --- setting off with a backpack full of camping supplies and

sketchbooks for a year-long expedition through Great Britain,

Australia, and Costa Rica.

In the end, what I remember most from that journey was the

homecoming. How American grocery stores seemed huge and slighly

obscene. How the dozens of boxes of books and clothes I'd stored

in my mother's basement seemed even more obscene --- what did I need

with so many possessions?

In a way, that trip was the beginning of my path toward

simplicity. Slipping

outside my own world, I saw myself in a completely new way. What

insight will this adventure bring?

I've always said a cat would be worth its weight in gold if it could

pull weeds out of the garden.

I guess the next best thing is to have your cat keep you company while

you get the job done yourself.

No

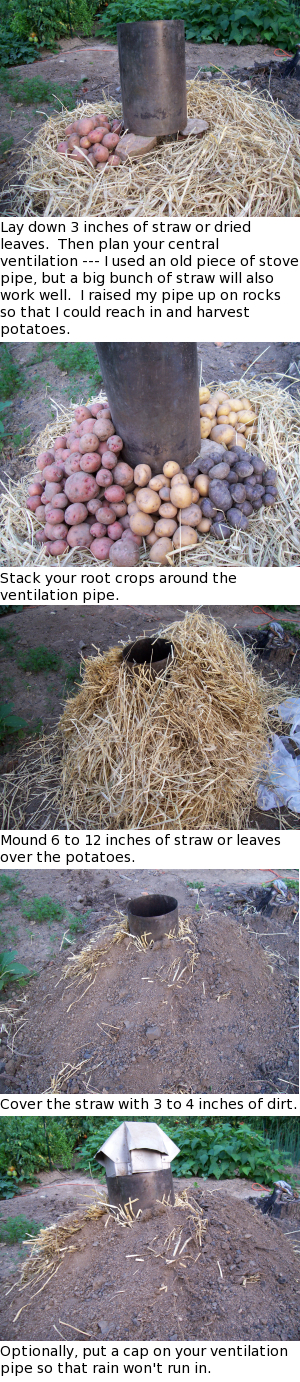

root cellar, but you still want to store root crops for the

winter? Don't despair --- storage mounds are cheap and easy to

build. You'll see a few more potatoes rot away than you would in

a good root cellar, but storage mounds are definitely worth the effort.

No

root cellar, but you still want to store root crops for the

winter? Don't despair --- storage mounds are cheap and easy to

build. You'll see a few more potatoes rot away than you would in

a good root cellar, but storage mounds are definitely worth the effort.

We tried out a simple

storage mound in 2007 that kept our potatoes fresh for months. If

I'd known what I know now, I suspect we would have had potatoes all the

way through to spring. What I did wrong:

- I dug my potatoes and stored them in August when the ground was still warm. I would have been better off leaving them in their rows until October.

- I put all of my potatoes in one mound, so I had to re-cover the mound every time I wanted a fresh potato. I would have been better off if I made several smaller mounds rather than one big mound.

- I should have stuffed straw down the ventilation pipe for additional insulation.

- I should have begun the mound slightly underground for better

insulation. Digging eight to twelve inches down before laying

down the first mulch layer works well.

- I wrapped a piece of plastic around my mound, hoping to keep the dirt from washing away in the rain. Bad idea! You want plenty of ventilation in your storage mound, so leave the plastic off.

Storage mounds --- also

known as "clamps" --- won't work well in the extreme north or the

extreme south, but if you have moderate winter temperatures, lots of

root crops, and no root cellar, they're worth a shot. Be sure to

build your clamps in a well-drained location. Potatoes, carrots,

beets, turnips, cabbage, parsnips, and apples can all be successfully

stored in clamps.

Check out our storage

vegetable series for more information about planting, harvesting,

and curing crops for fresh winter eating.

| In addition to rivetting

information about soil, Robert Kourik's Designing

and Maintaining Your Edible Landscape Naturally

is chock full of what may be my very favorite thing in life --- well

researched lists! I took copious notes and even made a few

spreadsheets, preparing for the hard day when I have to return the book

to the library. Now, I understand that some of you may find lists less tantalizing than I do. In fact, my father told me that spreadsheets give him shivers, and not the excited ones they give me. So, I promise you some tempting tidbits along with the lists. And for you list-lovers --- start salivating now! These lists are good! |

|

This post is part of our lunchtime series reviewing Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining your

Edible Landscape Naturally.

Read all of the entries:

|

When building a wooden holder for the Avian Aqua Miser one must

remember to allow a bit of wiggle room for the container to slide in

and out easily. Even though the hens don't seem to mind the tilt, a

simple back bracket is all it takes to even things out for a more

balanced look.

Mark wants to live in a

round house some day, and I have to admit that the idea has merit every

time I go visit Joey's yurt. The circles and lines in the yurt

always capture my interest and I end up taking photos that could almost

be abstract, like the one on the left.

Joey considered taking the yurt down for the winter, but instead he

bought a Two

Dog Stove, specially designed for safe use in tents. The

stove is so small that Joey was able to carry it in by himself soon

after our most

recent flood. Setup took mere minutes with the ultra-cool

telescoping stove pipe --- no need to laboriously fit pieces together;

just grab both ends and puuuullll.... I'm curious to see how well

the stove keeps Joey warm during his wintry visits to the farm.

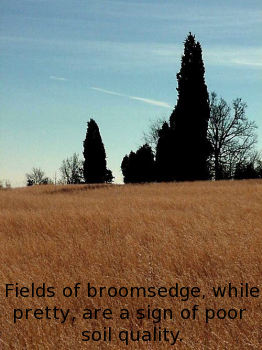

Imagine for a minute that you just moved onto

a large farm, the way we did three years ago. How do you know

where the soil is ideal for a garden? Soil tests are a good move,

but it would cost an arm and a leg to decipher the microhabitats that

cover even a quarter of an acre on our farm. You can do what I

did and just plant things randomly and watch half of them die, or you

can use Robert Kourik's list of indicator plants to find good and poor

garden spots.

Imagine for a minute that you just moved onto

a large farm, the way we did three years ago. How do you know

where the soil is ideal for a garden? Soil tests are a good move,

but it would cost an arm and a leg to decipher the microhabitats that

cover even a quarter of an acre on our farm. You can do what I

did and just plant things randomly and watch half of them die, or you

can use Robert Kourik's list of indicator plants to find good and poor

garden spots.

Is your yard overrun with hopclover and whitetop aster? Chances

are your soil is excessively alkaline and needs some acidification

before it will make good garden ground. What if you've got a lot

of sheep sorrel, goldenrod, and field bindweed? That means your

soil is sandy.

I took Robert Kourik's three page list of indicator plants and compiled

all of the ones that live in Virginia and the surrounding area, adding

in an indicator plant or two of my own. The resulting spreadsheet

is easy to sort by category so that you can see all of the wetland or

cultivated land indicators in one spot --- oh the wonders of

technology! Download my Virginia soil

indicator plants spreadsheet and enjoy!

This post is part of our lunchtime series reviewing Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining your

Edible Landscape Naturally.

Read all of the entries:

|

I was walking by the bee hives today and noticed this crowding by the

entrance. No doubt it's due to it being cold this morning, but a steady

flow of bees were going and coming which makes me wonder how they

decide who gets to stay home on a cold day like this one?

There's nothing more

depressing than picking one of the two watermelons

in your garden, cutting it open, and discovering that it's not yet

ripe. That's what happened in our garden last year, so this year

we grew more watermelons and started learning the secrets to

ensure we only pick the watermelons when they are fully ripe.

Some folks say they can tell when their watermelons are ripe by

thumping the side and listening for a hollow sound. Good

luck. Others count the days since they planted their seeds and

look at the days to maturity on the seed packet --- this is a good

start, but doesn't factor in chilly weather droughts, and other

features that set your ripening back by a day, a week, or a month.

I've found two signs that seem to be much more fail-safe. A ripe

watermelon will turn yellow, tan, or white on the portion touching the

ground --- the Sugar Baby in the photo on the left is a great

example. This pale spot can be harder to see on lighter green

watermelons, like the Dixie Queen on the right. Here, I focus on

the tendrils directly opposite the stem running to the

watermelon. Once these tendrils start to dry up and turn brown,

your watermelon should be juicy and sweet.

As a final note, we grew four varieties of watermelons this year ---

Sugar Baby, Dixie Queen, Early Moonbeam, and Sweet Favorite

Hybrid. Sugar Baby won the prolific fruit prize and Dixie Queen

won the taste test (but had very few fruits.) Early Moonbeam was

more of a novelty melon, with its yellow flesh, while we never actually

got a fruit from the Sweet Favorite Hybrid. It's always worth

planting several varieties if you have a fruit or vegetable that

doesn't seem to be working for you --- chances are that one of the

varieties will become your garden's new star!

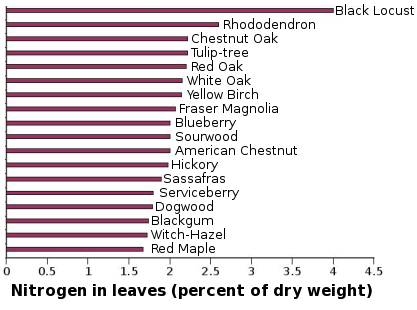

Once you know the

shortcomings of your soil, you can start planning green manures,

mulches, and herbal leys to correct deficiencies. All three of

these fertility campaigns are built around dynamic

accumulators ---

plants that concentrate micro and macronutrients from the soil into

their leaves, stems, and roots. Robert Kourik's book seems to be

the source of most of the data in more current books and websites about

dynamic accumulators, and once again I compiled the most useful species

into a dynamic accumulator

spreadsheet.

Once you know the

shortcomings of your soil, you can start planning green manures,

mulches, and herbal leys to correct deficiencies. All three of

these fertility campaigns are built around dynamic

accumulators ---

plants that concentrate micro and macronutrients from the soil into

their leaves, stems, and roots. Robert Kourik's book seems to be

the source of most of the data in more current books and websites about

dynamic accumulators, and once again I compiled the most useful species

into a dynamic accumulator

spreadsheet.

Looking for a

calcium-rich plant to help harden your chicken's eggshells? Why

not grow some comfrey or dandelions. Need to boost the nitrogen

content of low fertility soil? Clovers and vetches are hard to

beat, but you might also be able to gather high nitrogen tobacco-stalks

from your tobacco-growing neighbors.

All summer, as I dragged

our heaviest chicken tractor up and down a steep hill in the mule

garden, I've been considering planting a dynamic accumulator patch

there to be mowed at intervals, providing fertility to nearby garden

beds. It turns out that this concept has a formal name --- an

herbal ley. The term herbal ley technically refers to a pasture

of mixed grasses, legumes, and herbs, but I see no reason why I can't

use a similar patch to feed my darling fruit trees and

vegetables. I'll be playing with my dynamic accumulator

spreadsheet this winter to come up with a mixture of plants that

provides a well-rounded assortment of nutrients.

This post is part of our lunchtime series reviewing Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining your

Edible Landscape Naturally.

Read all of the entries:

|

The Club Car continues to be a work horse for

hauling in heavy loads, even during this wetter than usual spell we've

been going through.

The Club Car continues to be a work horse for

hauling in heavy loads, even during this wetter than usual spell we've

been going through.

I think it's time to consider building a frame towards the back to

upgrade the carrying capacity from 2 full golf club bags to something

more farm appropriate.

As a budding beekeeper,

I've learned that most stinging insects aren't so bad. Honeybee

stings stop hurting in minutes, the wasps that move into our trailer in

search of ladybugs rarely sting, and bumblebees generally mind their

own business. But I have a hard spot in my heart for

yellowjackets.

Last year was the worst year ever for yellowjackets --- it seemed like

every time I mowed the yard, I got stung. This year, we only seem

to have one nest within our cultivated perimeter (and another along the

driveway). Since I've marked the locations and give them a wide

berth, stings have been relatively minor.

I've been stung

by pretty much everything out there, and I have to say that

yellowjacket stings are the most painful. All summer, I've

considering finding a way to kill the colony living between my rhubarb

and asparagus, but I can't wrap my mind around poison. Turns out

I've waited long enough that winter will soon do it for me.

Unlike honeybees where most of the colony survives the winter, only the queen

yellowjacket overwinters, starting a new colony in the

spring. Sure is nice to be able to put off one more problem until

next year....

In the rush to produce the

world's biggest pumpkin and the world's tastiest strawberries, it's

easy to ignore flowers. But flowering plants should have a

prominent place in any organic garden since they attract beneficial

insects. Everyone knows that ladybugs are the cat's meow, but did

you know that hover flies (also known as syrphid flies) are great

aphid-eaters and that tiny parasitic wasps will eat your pest insects

from the inside out?

In the rush to produce the

world's biggest pumpkin and the world's tastiest strawberries, it's

easy to ignore flowers. But flowering plants should have a

prominent place in any organic garden since they attract beneficial

insects. Everyone knows that ladybugs are the cat's meow, but did

you know that hover flies (also known as syrphid flies) are great

aphid-eaters and that tiny parasitic wasps will eat your pest insects

from the inside out?

The problem with

attracting beneficial insects is that there are a dozen or more key

insect players, and each one needs to be fed supplemental pollen and

nectar all through the growing season. Luckily, many plants

support several different kinds of beneficial insects, especially

plants like umbellifers, composites, and mints that host scores of tiny blooms.

I compiled another spreadsheet to help me keep track of all

of the different nectary plants for beneficial insects, starting with

the ones listed in Robert Kourik's book but expanding out to include

plants listed on Farmer

Fred's website.

It's clear that fennel, goldenrod, and Queen Anne's lace are top

nectary plants, while ragweed appears to be as beloved by some species

as it is by our honeybees. Stay tuned for more nectary musings as

I plan next year's garden.

This post is part of our lunchtime series reviewing Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining your

Edible Landscape Naturally.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our lunchtime series reviewing Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining your

Edible Landscape Naturally.

Read all of the entries:

|

It's been over a year since our phone line was cut in half by some

reckless weed eating on my part. At the time I just stripped each wire

and wrapped them together with a bit of electrical tape for protection.

Well that kind of repair will only last so long if it's subjected to

the outside elements.

I had to repeat that fix twice last winter due to moisture getting into

the taped area and knocking out our phone service. Also the twisting of

the wires can sometimes cause them to become weak and break.

I was quizzing our local radio shack guy on this last week hoping to

find a clever solution and he came through with these phone splice

connectors. Expect to spend just under a buck for each one, and get 2

packages if you need more than 4 wires spliced like most phone cables.

It's really easy. You just slide each wire all the way in and crimp

down with a set of pliers. Make sure you press hard.

We're

home, safe and sound! Two purring cats, an ecstatic dog, three

tractors of happy chickens. Deer damage in the garden --- I will

consider it a tithe to the earth for our stunning cruise

adventure. Plenty of orders for our homemade chicken

waterer ---

yay! The earth smells of damp leaves and the creek is middlin'

high.

We're

home, safe and sound! Two purring cats, an ecstatic dog, three

tractors of happy chickens. Deer damage in the garden --- I will

consider it a tithe to the earth for our stunning cruise

adventure. Plenty of orders for our homemade chicken

waterer ---

yay! The earth smells of damp leaves and the creek is middlin'

high.

We'll be more talkative later. For now, I'm just glad to be home!

Now that we're home from our

journey, it's time to bring my obsession with Robert Kourik's book to

an end too. Where better to end than with my greatest weakness

--- fruit trees?

Now that we're home from our

journey, it's time to bring my obsession with Robert Kourik's book to

an end too. Where better to end than with my greatest weakness

--- fruit trees?

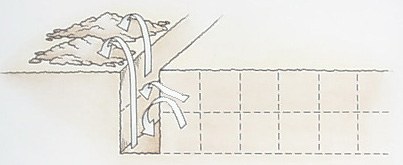

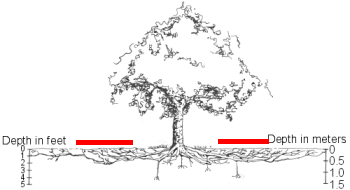

Robert Kourik's book

threw everything I thought I knew about fruit trees on its head.

You know how the roots of trees extend as far vertically and

horizontally underground as the tree's canopy spreads

aboveground? That's bunk. In fact, tree roots often grow

1.5 to 3 times as wide as the canopy of the tree. And while some

vertical roots sink deep to give the tree stability, the majority of

the tree's feeding is done in the top two to four feet of the soil,

with the primary focus on the top few inches.

What does this mean for

folks planting a little orchard in their backyard? Many of us

mulch our trees to prevent them from having to compete with grass for

nutrients --- if we do that, we should be mulching much further out

than the cute donut around the trunk. In fact, Kourik recommends

planting a cover crop close to the trunk of the tree and instead

focusing your mulch on the area halfway between the trunk and the

dripline of the tree, then continuing the same distance beyond the

dripline of the tree. (I've marked this area with a red line in

the diagram above.)

If all of this talk of

roots has whetted your appetite like it has mine, you might want to

check out one of Robert Kourik's more recent books --- Roots

Demystified.

My copy is already on hold through the interlibrary loan system.

This post is part of our lunchtime series reviewing Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining your

Edible Landscape Naturally.

Read all of the entries:

|

Sailing on the cruise ship Holiday is considered the lower end of the

cruise industry, and our expedition was one of its last voyages before it

gets retired next month.

It's hard to believe this level of luxury is considered out of date. We

had a stellar time aboard the Holiday and have managed to sum it all up

with a couple of videos and some pictures for next week's lunch time

series.

This post is part of our Moundville and Cruise to Mexico honeymoon

series.

Read all of the entries:

|

The frost kindly waited until our return to

threaten --- frost by the end of the weekend. Most major frost

preparations are long since complete, but I picked the last of the

everbearing red raspberries and Mexican sour gherkins, took in a

bowlful of green tommy-toe tomatoes, and picked the last big bowl of

shiitakes.

The frost kindly waited until our return to

threaten --- frost by the end of the weekend. Most major frost

preparations are long since complete, but I picked the last of the

everbearing red raspberries and Mexican sour gherkins, took in a

bowlful of green tommy-toe tomatoes, and picked the last big bowl of

shiitakes.

Meanwhile, our first day home glowered coldly at us, so I decided to

make some roast roots to warm up the house and our dispositions.

The  parsnip I dug clearly wasn't

quite ready yet, so I filled up our roasting pan with masses of

carrots, tiny sweet potatoes that need to be eaten ASAP, and white

potatoes, shiitakes, onions, garlic, thyme, and parsley, all from the

garden. Toss on a storebought chicken, and our dinner was nearly

as good as the ones on our cruise.

parsnip I dug clearly wasn't

quite ready yet, so I filled up our roasting pan with masses of

carrots, tiny sweet potatoes that need to be eaten ASAP, and white

potatoes, shiitakes, onions, garlic, thyme, and parsley, all from the

garden. Toss on a storebought chicken, and our dinner was nearly

as good as the ones on our cruise.

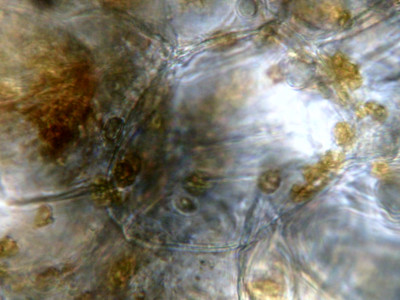

The second photo is a closeup of a carrot cell, showing the

chromoplasts that give the root its color. More on the fancy,

digital microscope the photo was taken with later.

In doing a little research on the ship we

sailed on I discovered it was one of three ships contracted by FEMA

after hurricane Katrina to provide housing for relief workers and

victims of the storm.

In doing a little research on the ship we

sailed on I discovered it was one of three ships contracted by FEMA

after hurricane Katrina to provide housing for relief workers and

victims of the storm.

Politicians from both parties criticized the deal due to the ships not

being fully utilized, but with a little hind sight it seems like it

was a quick decision in the face of a disaster that didn't quite work

out as planned.

I like the idea of relief workers having a comfortable place to

recharge after a long day or night of helping people as they try to put

various pieces back together. Maybe the government should consider

designing a ship with this purpose in mind?

This post is part of our Moundville and Cruise to Mexico honeymoon

series.

Read all of the entries:

|

The best book I read while on

our cruise

was Brad Kessler's Goat

Song: A Seasonal Life, a Short History of

Herding, and the Art of Making Cheese. The book traces the

first year in the author's life with Nubian milk goats, and I warn you

that after you finish it you will want milk goats too. I had to

remind myself repeatedly that I wouldn't have been able to leave the

farm if I got milk goats and thus wouldn't have been on the cruise.

The best book I read while on

our cruise

was Brad Kessler's Goat

Song: A Seasonal Life, a Short History of

Herding, and the Art of Making Cheese. The book traces the

first year in the author's life with Nubian milk goats, and I warn you

that after you finish it you will want milk goats too. I had to

remind myself repeatedly that I wouldn't have been able to leave the

farm if I got milk goats and thus wouldn't have been on the cruise.

The book was almost blog-like in parts, a format that I obviously

enjoy. One chapter ran through the highlights of a season of

milking, day by day, and another chapter was a blow by blow account of

cheese-making. He mixed in some monks, a visit to artisanal

cheese-makers in France, and the effects that herding has had on our

language and culture. When I closed the cover, I could almost

smell new hay, meadow flowers, and goat cheese lingering in our cabin.

Our tour of Uxmal in the Yucatan of Mexico was one of the highlights of

the cruise. We had an awesome tour guide by the name of Armando Chan

who was part Mayan. His words really added a nice element to our

understanding of this amazing culture.

The atmosphere of history is fascinating and we decided 3 hours was

just not enough time to explore such a mystical place. Maybe we can

plan for an extended adventure at Uxmal for our next Yucatan excursion?

This post is part of our Moundville and Cruise to Mexico honeymoon

series.

Read all of the entries:

|

We

got back home Thursday after dark, so I was shocked the next morning

when I stumbled out of bed, looked out the window, and saw huge blobs

of color on the hillside. Autumn leaves!

We

got back home Thursday after dark, so I was shocked the next morning

when I stumbled out of bed, looked out the window, and saw huge blobs

of color on the hillside. Autumn leaves!

Sunday, the cloudy weather broke for a few hours, and I took Lucy and

the camera out in the woods to explore. Mushrooms had popped up

all over and freshly fallen leaves were strewn around them.

Closer to home, our shiitake logs were all coated in mushrooms, despite

not being soaked in weeks. I guess this is perfect mushroom

weather --- cool and wet.

And now, Monday morning, the ground is thick with our first frost and

temperatures are in the mid 20s. Surely we haven't skipped

straight to winter?

Now

that we're back on land, it's time to bombard you with pictures and

stories of our adventures. We can't force you all to come over

and watch a mind-numbing, three-hour-long slide show, so instead this

week's lunchtime series covers the highlights. This way, rather

than falling asleep in the dark, you can just skip our posts if they

get too boring.

As we mentioned previously, before hopping on the cruise ship we spent

a day at Moundville's

Native American Festival, the highlight of which

was learning to make fire. I summed up the fire-making experience

in a four minute video --- my first effort at video editing, so please

excuse my growing pains. The expert on the video created an ember

out of two pieces of pine, a bow,

and a cap stone in less than three minutes. It didn't quite catch

in

his tinder due to humid Alabama weather, but the concept is

extraordinarily well explained. Watch and learn!

This post is part of our Moundville and Cruise to Mexico honeymoon

series.

Read all of the entries:

|

A friend of mine gracefully brought to my attention the fact that I was

ignoring the 6 inch freeze zone when I was laying the

ground work for our new building project.

I decided to experiment with some posts from the large cedar tree I cut

down last month. It's easier for an amateur like me to use this method

compared to leveling out the cinder blocks.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

At the end of last winter, Huckleberry tore

apart the air pipe that channels heat from our exterior wood

furnace into the trailer. Then the stove pipe rusted

out. We were trying to hold

off on lighting our wood stove until the end of the week when we would

hopefully have the floor of the shed up and could just move the stove

there, rather than fixing it in its current location.

At the end of last winter, Huckleberry tore

apart the air pipe that channels heat from our exterior wood

furnace into the trailer. Then the stove pipe rusted

out. We were trying to hold

off on lighting our wood stove until the end of the week when we would

hopefully have the floor of the shed up and could just move the stove

there, rather than fixing it in its current location.

All weekend, I shivered in a house that barely reached 50 degrees,

baking large dinners to warm up the kitchen. Mark had a space

heater in his room, but I didn't want to break down and use

electricity. Finally, Monday morning, the interior temperatures were in the

thirties. Yikes!

So sweet Mark threw

together some short-term fixes on the wood stove and lit us a

fire. By mid morning, I took off my winter coat, sweater, gloves,

and second pair of pants. Ah, wood heat!

As a side note, you can see that our wood shed is already halfway

full. It looks like we may run out of space before we run out of

wood and will have to build a second shed. A good problem to have!

We

also learned about two other intriguing Native American crafts at the

Moundville

festival --- cane baskets and pit-fired pottery. The

lady on the right is splitting a piece of river cane (a native bamboo)

in half, then in half again. Next, she will shave the top off

each quarter to make a strong, slender cane perfect for basket-weaving.

We

also learned about two other intriguing Native American crafts at the

Moundville

festival --- cane baskets and pit-fired pottery. The

lady on the right is splitting a piece of river cane (a native bamboo)

in half, then in half again. Next, she will shave the top off

each quarter to make a strong, slender cane perfect for basket-weaving.

River cane used to be ubiquitous throughout the South, and Native

Americans put it to good use, turning the canes into baskets, spears,

shelters, and much more. I was inspired by the demonstration to

work harder at planting our own mini cane brake where the power line

cut creates an opening in our floodplain forest.

Crowds

of school children pushed us onward, past the basket-weaver to the

pit-fired pottery demonstration. I took pottery classes in high

school and college and loved the feel of mud on my hands, but always

found the kiln infrastructure too daunting to try on my own.

Native Americans, of course, used simpler techniques than electric

kilns. Instead, they dug shallow pits about a foot deep, placed

pots on a mound in the center, and built a fire around the edges.

The fire starts small, but is slowly allowed to engulf the pots over

the course of five to six hours, turning the pots first black then back

to clay color. Again, I resolved to try to mine a bit of the clay

along our creekbank and give pit-firing a shot.

Crowds

of school children pushed us onward, past the basket-weaver to the

pit-fired pottery demonstration. I took pottery classes in high

school and college and loved the feel of mud on my hands, but always

found the kiln infrastructure too daunting to try on my own.

Native Americans, of course, used simpler techniques than electric

kilns. Instead, they dug shallow pits about a foot deep, placed

pots on a mound in the center, and built a fire around the edges.

The fire starts small, but is slowly allowed to engulf the pots over

the course of five to six hours, turning the pots first black then back

to clay color. Again, I resolved to try to mine a bit of the clay

along our creekbank and give pit-firing a shot.

This post is part of our Moundville and Cruise to Mexico honeymoon

series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Yes.....a couple of the mechanical

deer deterrents failed recently due to some simple hang ups. It

took me a few attempts before I came up with what I call the supporting

arm structure for the clanging surface.

The support provides more adjustment choices when fine tuning the swing

and helps to secure this deer deterrent contraption even during heavy

winds.

Is a failure like this frustrating? Heck yeah it is, but the feeling of

knowing we are one step closer to a better solution helps to ease the

pain.

Our chickens are pretty self-sufficient as

long as the temperature doesn't get too far below freezing. We've

been known to leave them for up to four days with just an extra automatic chicken waterer and

a few scoops of feed sprinkled over the ground. The only problem

with leaving them alone for so long is that they scratch the ground up

pretty badly, and in rainy weather the soil turns into a morass of mud.

Our chickens are pretty self-sufficient as

long as the temperature doesn't get too far below freezing. We've

been known to leave them for up to four days with just an extra automatic chicken waterer and

a few scoops of feed sprinkled over the ground. The only problem

with leaving them alone for so long is that they scratch the ground up

pretty badly, and in rainy weather the soil turns into a morass of mud.

Before heading out on our cruise, I decided to try a different

tactic. I begged Mark to rake me

up a bunch of leaves, and I filled each tractor with a mountain of

organic matter. When we returned a week later, each mountain had

sunk to a mole hill of shredded leaves well mixed with chicken poop,

but the ground wasn't muddy despite an inch and a half of rain.

I'm emulating the traditional

Guatemalan method of using this combination as a well-balanced soil

amendment, though I plan to use the poopy mass as mulch on my garlic

beds rather than working it into the soil.

After

Moundville,

we got on the boat for our five day cruise. I had

been concerned that spending so much time at sea might be a bit boring,

but instead the experience was so astounding that we'll definitely

repeat it soon. I summed it up in my second editted video ---

this one's shorter and tighter than the last one, I promise.

This post is part of our Moundville and Cruise to Mexico honeymoon

series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Yesterday we figured out the hard way what

happens when you exceed the load limit in the heavy

hauler trailer we use with the golf cart.

Yesterday we figured out the hard way what

happens when you exceed the load limit in the heavy

hauler trailer we use with the golf cart.

Normally it seems to be able to handle a full load of wood half haphazardly thrown in, but when you carefully stack each log next to

its neighbor the volume increases to the point of a problem.

I heard a loud pop coming from the driveway where Anna was hauling

firewood and knew some sort of tire mishap had occurred.

I think they sell these replacement wheels at the big box stores, or

maybe we'll get lucky and our tire guy will work another rubber miracle

by bringing it back to a functional life for a small fee?

This post is a continuation of the

never-ending saga of the weird growing year. Remember how things

like potatoes that are supposed to be carefree kicked the bucket?

Well, our carrots --- which many people find difficult --- grew like

kudzu.

This post is a continuation of the

never-ending saga of the weird growing year. Remember how things

like potatoes that are supposed to be carefree kicked the bucket?

Well, our carrots --- which many people find difficult --- grew like

kudzu.

Wednesday, I harvested two beds and came up with 27 pounds of carrots,

enough to completely fill the crisper drawer of our little

fridge. Many of the carrots were as big as or bigger than

store-bought, and I suspect they will store for months if I can keep

the moisture level correct.

We've got four beds left to harvest, but I planted those beds late so

the carrots are smaller. I plan to give those to my brother and

mother so that they, like us, will turn orange by spring.

Of

course, being who I am, as soon as the tour guide turned me loose I

headed in the opposite direction from the rest of the group, toward the

woods. The Yucatan Peninsula is covered with dry, scrub forest

due to very thin topsoil over limestone. Trees were short, and

many were legumes --- presumably the poor soil gives trees that can

make their own nitrogen an advantage. Butterflies abounded, as

did huge iguanas that had taken up residence in the abandoned rooms all

around the ruins. Swallows soared and chittered, Africanized

honeybees gathered pollen in the grass, and Mark and I sat in the shade

and lived Uxmal.

This post is part of our Moundville and Cruise to Mexico honeymoon

series.

Read all of the entries:

|

It's always a nice bonus when Lucy gives a project

a few sniffs and then announces her seal of approval.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

Some

of you may be wondering about our decision to use untreated cedar posts

as the foundation of our

shed. It

almost certainly wouldn't pass the building inspector's eagle eye, but

luckily small sheds are often exempt from code restrictions (especially

when you live out in the middle of nowhere.)

Some

of you may be wondering about our decision to use untreated cedar posts

as the foundation of our

shed. It

almost certainly wouldn't pass the building inspector's eagle eye, but

luckily small sheds are often exempt from code restrictions (especially

when you live out in the middle of nowhere.)

How long will the red

cedar posts last in the ground? Your guess is as good as mine,

but I suspect they'll last a good long while. Red Cedar (Juniperus

virginiana) wood contains substances that

naturally kill termites, but it's hard to say

whether the wood is as effective against fungal rots.

The red heartwood, from

which Red Cedar gets its name, is the most hardy part. Mark

carefully chose large cedar trunks with plenty of heartwood, figuring

that even if the pale sapwood rots away, enough heartwood will remain

to support our shed. People have been using Red Cedar as

untreated fenceposts for a long time, and Mother

Earth News notes that they will last for 15 to 20 years. Since our supports

are significantly thicker than typical fenceposts and will be protected

on the top from water, I wouldn't be surprised if they lasted for

several decades.

At Uxmal, we learned that Mayans

traditionally tore down their homes and started fresh every 52

years. It just makes sense to me to create a structure that uses

fewer resources (and costs less money), but that will need care and

maybe will even have to be replaced in our lifetime. So far,

we're on track to build the shed for around $6 per square foot,

including insulation. At that rate, we could rebuild our shed

every 5 years for the rest of our lives and still come out ahead of

someone who used more traditional methods.

| This post is part of our Building a Storage Building from Scratch

series.

Read all of the entries: Part 1: Foundation

Part 3: Walls and scavenging lumber

Part 5: The roof

|

Our

second day on shore, we decided to take it easy --- our excursion to

Uxmal had both worn us out and drained our wallets. Instead, we

got off the boat on the island of Cozumel and simply explored. We

ran the gauntlet, passing vendors trying to lure us into their booths,

taxi-drivers anxious to take us for a ride, and time-share salesmen.

Our

second day on shore, we decided to take it easy --- our excursion to

Uxmal had both worn us out and drained our wallets. Instead, we

got off the boat on the island of Cozumel and simply explored. We

ran the gauntlet, passing vendors trying to lure us into their booths,

taxi-drivers anxious to take us for a ride, and time-share salesmen.

The water was the stunning turquoise you see in photographs and never

quite believe and so clear that we could look down from the pier and

see fish swimming several feet below. I was intrigued by the

plant life in a vacant lot, full of species I had no way of

identifying. One, though, especially caught my eye --- could that

be Mexican

Sour Gherkin climbing wildly over a fence? I was 98%

sure the plant was at least a relative, but decided against nibbling on

its fruits.

After

walking for a couple of hours in the heat, trying to reach an elusive

museum, Mark found us an out of the way corner to relax against a

replica Mayan statue. We posed for photos, let a little Mexican

rain sprinkle on our heads, then headed back to the ship for a stunning

meal and a nap.

After

walking for a couple of hours in the heat, trying to reach an elusive

museum, Mark found us an out of the way corner to relax against a