North American native permaculture

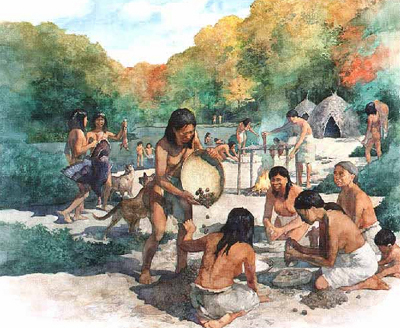

Before

eastern Native Americans domesticated the crops in the Eastern

Agricultural Complex,

they still relied heavily on plants for their

nutrition. Between 8000 BC and 2000 BC (the so-called Archaic

period), Native Americans in our area ate a variety of un-domesticated

native

plants, including the fruits of sumac, blackberry, grape,

hackberry, hawthorn, plum, pawpaw, cherry, mulberry, and persimmon; the

nuts of hickory, oak, hazel,

walnut, chestnut, beech, and pecan; and the sweet insides of honey

locust pods. They also ate the fruits, leaves, or tubers of

Jerusalem artichoke,

two wild beans, groundnut, maypop, black nightshade, amaranth,

pokeweed, carpetweed,

dock, chickweed, ground cherry, purslane, carpetweed, panicgrass, hog

peanut, and a

spurge. Most of these plants continued to be important in the

Native American diet for thousands of years thereafter.

Before

eastern Native Americans domesticated the crops in the Eastern

Agricultural Complex,

they still relied heavily on plants for their

nutrition. Between 8000 BC and 2000 BC (the so-called Archaic

period), Native Americans in our area ate a variety of un-domesticated

native

plants, including the fruits of sumac, blackberry, grape,

hackberry, hawthorn, plum, pawpaw, cherry, mulberry, and persimmon; the

nuts of hickory, oak, hazel,

walnut, chestnut, beech, and pecan; and the sweet insides of honey

locust pods. They also ate the fruits, leaves, or tubers of

Jerusalem artichoke,

two wild beans, groundnut, maypop, black nightshade, amaranth,

pokeweed, carpetweed,

dock, chickweed, ground cherry, purslane, carpetweed, panicgrass, hog

peanut, and a

spurge. Most of these plants continued to be important in the

Native American diet for thousands of years thereafter.

If you've ever picked up a

book on eastern

North American edible

plants, you'll have

noticed that most of the top edibles are listed above.

So the Native Americans just figured out what was edible and they

wandered around all day looking for them, right? In Cultivated

Landscapes of Native North America,

William E. Doolittle makes a strong case for the hypothesis that most

or all of these "wild"

plants were cultivated to some extent, even though they weren't

domesticated. You'll notice that nearly all of the woody plants

listed aren't old growth species and instead require some space and

extra sunlight to produce plenty of fruits. Native Americans cut

the competition away from favored plants, burned out the undergrowth,

pruned trees and vines to make fruits larger and easier to harvest, and

transplanted edible-fruited trees to the edges of their fields after

they began growing domesticated crops. A great deal of evidence

exists to suggest that grapes were propagated by cuttings and planted

in vineyards, mulberry trees were planted near homes, and chickasaw

plums and pecans were carried east from their natural range to plant

throughout the South.

If you've ever picked up a

book on eastern

North American edible

plants, you'll have

noticed that most of the top edibles are listed above.

So the Native Americans just figured out what was edible and they

wandered around all day looking for them, right? In Cultivated

Landscapes of Native North America,

William E. Doolittle makes a strong case for the hypothesis that most

or all of these "wild"

plants were cultivated to some extent, even though they weren't

domesticated. You'll notice that nearly all of the woody plants

listed aren't old growth species and instead require some space and

extra sunlight to produce plenty of fruits. Native Americans cut

the competition away from favored plants, burned out the undergrowth,

pruned trees and vines to make fruits larger and easier to harvest, and

transplanted edible-fruited trees to the edges of their fields after

they began growing domesticated crops. A great deal of evidence

exists to suggest that grapes were propagated by cuttings and planted

in vineyards, mulberry trees were planted near homes, and chickasaw

plums and pecans were carried east from their natural range to plant

throughout the South.

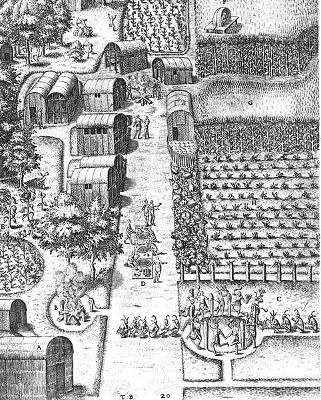

Smaller edibles were also encouraged in much

the same way that a modern

gardener might let a volunteer vegetable alone once he recognizes its

worth. A wide range of small plants weren't completely dependent

on the Native Americans for their care (like the Eastern Agricultural

Complex was) but still benefited from a bit of encouragement and were

then eaten. Many of the plants listed in the last sentence of the

first paragraph are

weedy species that require some disturbance in order to grow, so they

sprang up in the Native American's cultivated fields. At the time

of European contact, it was common to see maypops, Jerusalem

artichokes, and other "weeds" allowed to grow in the corn fields, to be

harvested for food.

Smaller edibles were also encouraged in much

the same way that a modern

gardener might let a volunteer vegetable alone once he recognizes its

worth. A wide range of small plants weren't completely dependent

on the Native Americans for their care (like the Eastern Agricultural

Complex was) but still benefited from a bit of encouragement and were

then eaten. Many of the plants listed in the last sentence of the

first paragraph are

weedy species that require some disturbance in order to grow, so they

sprang up in the Native American's cultivated fields. At the time

of European contact, it was common to see maypops, Jerusalem

artichokes, and other "weeds" allowed to grow in the corn fields, to be

harvested for food.

Although the native

North American systems of encouraging wild plants

weren't as intricate as the forest gardens you see in the tropics, the

widespread range and abundance of many of the species mentioned in this

post can probably be

linked back to the continent's earliest human inhabitants. It

begs the question --- are you really wildcrafting when you harvest the

ubiquitous pokeweed growing behind your house, or are you just eating

the remains of a Native American garden?

| This post is part of our Native American Paleoethnobotany lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.