archives for 04/2011

What

does our garden look like at the end of March? Mostly, it looks

like lettuce --- great big gobs of brilliantly green leaves to eat

every day. We've been nibbling on lettuce for about a fortnight,

but only in the last week has the growth reached the point that salad

is a daily affair. Mark showed me that I can carefully lift the

edges of the quick

hoop up without

tearing the fabric, so I've decided

the beds are even easier to get into than my old cold frames were, and

the speedy access means I think nothing of running out to cut a salad

for

lunch.

What

does our garden look like at the end of March? Mostly, it looks

like lettuce --- great big gobs of brilliantly green leaves to eat

every day. We've been nibbling on lettuce for about a fortnight,

but only in the last week has the growth reached the point that salad

is a daily affair. Mark showed me that I can carefully lift the

edges of the quick

hoop up without

tearing the fabric, so I've decided

the beds are even easier to get into than my old cold frames were, and

the speedy access means I think nothing of running out to cut a salad

for

lunch.

Egyptian onions are growing far

faster than we can eat them at the

moment, and the parsley is finally coming out of its winter

slump. The parsley

plants that I seeded last fall survived the

winter and would probably be pretty big if I hadn't been snipping off

nearly every new leaf as soon as it appears starting in February.

Add in eggs --- the other mainstay of the spring diet --- and you've

got the best egg salad we've ever eaten.

Egyptian onions are growing far

faster than we can eat them at the

moment, and the parsley is finally coming out of its winter

slump. The parsley

plants that I seeded last fall survived the

winter and would probably be pretty big if I hadn't been snipping off

nearly every new leaf as soon as it appears starting in February.

Add in eggs --- the other mainstay of the spring diet --- and you've

got the best egg salad we've ever eaten.

We're also trying to eat

up (or freeze) the last of the butternuts

before their centers get too dry. The potatoes

in the crisper

drawer of the fridge

are good for months yet, but the sweet potatoes

are developing bad spots --- my fault for letting them sit on the cold

floor through the deepest part of the winter. The same

problematic storage conditions are tempting my garlic to sprout.

It looks like we're going to have enough storage

vegetables to carry us through despite these problems, and we're

already losing interest in winter fare as

the fresh garden goodies begin to roll in.

Nearly everything I've

planted this spring is already up and running

--- storage onions both in the quick hoops and out, broccoli and

cabbage sets in quick hoops, Asian greens and swiss chard in the

open. Breadseed poppies are thriving and our second planting of

peas is already up and growing, though the earlier seedlings are

about three inches taller. I'm still waiting on parsley, carrots,

spinach, and garbanzo beans to poke above the soil surface, but given

our frequent rains this week, I suspect they've already

germinated. Even the chicory seeds I tossed on new hugelkultur mounds

in the forest garden have sprouted.

Nearly everything I've

planted this spring is already up and running

--- storage onions both in the quick hoops and out, broccoli and

cabbage sets in quick hoops, Asian greens and swiss chard in the

open. Breadseed poppies are thriving and our second planting of

peas is already up and growing, though the earlier seedlings are

about three inches taller. I'm still waiting on parsley, carrots,

spinach, and garbanzo beans to poke above the soil surface, but given

our frequent rains this week, I suspect they've already

germinated. Even the chicory seeds I tossed on new hugelkultur mounds

in the forest garden have sprouted.

Next up --- tomatoes in

a quick hoop next week and lettuce out in the

open. I've started peppers inside and will be transplanting

broccoli and cabbage seedlings out of their protective covering as soon

as the plants get a few true leaves. Otherwise, though, I'm

looking forward to the April garden "lull" to give me time to weed and

mulch our existing beds and prepare the soil for the huge May rush.

Although

it's helpful to get an idea of which common foods are good or bad for

you, I think it's more important to recalibrate our intake of the major

food groups. Michael Barbee presents one recommendation for

overall nutrition (shown here), but he also cautions that the best diet

is

individualized. Paying attention to how your body feels when you

eat certain foods is the best way to develop a personal diet that's

healthiest for you. Our bodies' needs also change over time, so

we

have to be flexible enough to realize that what suited us last year

might not suit us tomorrow.

Although

it's helpful to get an idea of which common foods are good or bad for

you, I think it's more important to recalibrate our intake of the major

food groups. Michael Barbee presents one recommendation for

overall nutrition (shown here), but he also cautions that the best diet

is

individualized. Paying attention to how your body feels when you

eat certain foods is the best way to develop a personal diet that's

healthiest for you. Our bodies' needs also change over time, so

we

have to be flexible enough to realize that what suited us last year

might not suit us tomorrow.

That said, we should all

ditch the USDA food pyramid. Michael

Barbee suggests that the caveman diet is a good place to start instead

when

recalibrating our food sensors. Pre-agricultural

man got about

half his calories from wild game and rounded out his diet with nuts,

seeds, eggs, fruits, vegetables, insects, and worms. Dairy,

grains, and legumes are newer additions to the human diet, cause many

of us problems, and should probably be consumed only in moderation by

everyone.

As I mentioned earlier,

Mark and I have changed our eating habits

drastically in the last year. We've lowered our intake of grains,

potatoes, and other carbohydrates to one to two servings per day and

have increased our fats and protein to fill in the gap. We also

boosted fruits and vegetables, aiming for these goodies to

fill around two-thirds of our plate at every meal (with a bit more

carbs on Mark's plate since he seems to need more.)

Astonishingly, this changed dietary regime has stopped many of our food

cravings, toning down my chocaholic tendencies and finally breaking

Mark free from his dependence on snack crackers. I wonder if we

had some kind of nutritional imbalance that got corrected by changing

the way we eat?

| This post is part of our Politically Incorrect Nutrition lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

A potential escape spot in

any chicken

fence is where the ground meets the wire.

I like using old logs that

are way past the point of firewood. Sometimes I'll lay them on top of

the wire and other times it works out better to have the log on the

bottom depending on if there's any slope to deal with.

Old boards from the broken

down house worked as the same function, but you don't get the bugs and

worms that come along with a punky log.

Almonds are one of my new

favorite foods, so I decided to see if we could grow them.

Traditionally, almonds are grown in the sunny south, especially in

California where summers are dry, but orchardists have recently

developed hardy almonds that can live all the way north to zone

5. We chose Alenia (Prima) and Dessertniy (Bounty) because they

are late-blooming (which means less likely to succumb to our frequent

spring frosts), have thin shells, and are supposed to have tasty

nuts. (Bitterness can be a problem with some almond varieties.)

Almonds are one of my new

favorite foods, so I decided to see if we could grow them.

Traditionally, almonds are grown in the sunny south, especially in

California where summers are dry, but orchardists have recently

developed hardy almonds that can live all the way north to zone

5. We chose Alenia (Prima) and Dessertniy (Bounty) because they

are late-blooming (which means less likely to succumb to our frequent

spring frosts), have thin shells, and are supposed to have tasty

nuts. (Bitterness can be a problem with some almond varieties.)

The main problem people

report with growing almonds in the east is fungal diseases that result

from our wet summers. To nip fungi in the bud, we've sited our

new trees in the sunniest part of the yard and given them a bit more

air space than they require (planting them 20 feet apart rather than

the rated 10 to 15 feet.) Unfortunately, this area is on a slope,

but I built cepa terraces for our trees to make them

easier to tend and to capture rainwater for the roots.

Those of you with the

keenest eyes have probably noticed that our new almond beds are in the chicken pasture. We moved our flock on

to pasture two on Friday, giving me some breathing room to plant

almonds and grapes in the old pasture. Before rotating the

chickens back to this pasture, we'll make some simple tree cages out of

chicken wire to keep the birds from scratching up my new plantings.

The Pro Line hip waders came

in the mail the other day and I got a chance to take them out for a

test drive.

A little extra effort to put

on, but well worth it compared to walking

across the creek in my boxer shorts trying to keep my pants dry.

A

cold week slowed down decomposition action in our worm bin. I'd gotten used to

seeing worms in last week's bedding when I went to put in the next

week's scraps, but this Friday the worms seemed to be hanging out only

in the older food. I'll cut back a bit on the amount of food I

add to the bin while waiting for warm weather to return.

A

cold week slowed down decomposition action in our worm bin. I'd gotten used to

seeing worms in last week's bedding when I went to put in the next

week's scraps, but this Friday the worms seemed to be hanging out only

in the older food. I'll cut back a bit on the amount of food I

add to the bin while waiting for warm weather to return.

I wonder if our worms

were huddled up into these clusters to stay warm, or if every worm just

happened to want to eat the same tasty morsel?

I've had good luck weaving a

strand of electric fence wire up and down a post to secure the wire in

place.

Cut the strand just a little

longer than the height of the post. I prefer to start at the bottom and

weave my way up, which seems a little easier than starting at the top.

Our honeybees have been

coming out to fly during warm spells all through March, and we started

seeing native

pollinators two

weeks ago, but Sunday was the day when the whole farm began to

buzz. Both the flowers and the insects were just waiting for the

week of cold, rainy weather to let up, and when the frost melted and

the sun came up, the honeybees almost seemed to be prying our kitchen

peach flowers open.

Our honeybees have been

coming out to fly during warm spells all through March, and we started

seeing native

pollinators two

weeks ago, but Sunday was the day when the whole farm began to

buzz. Both the flowers and the insects were just waiting for the

week of cold, rainy weather to let up, and when the frost melted and

the sun came up, the honeybees almost seemed to be prying our kitchen

peach flowers open.

Fruit

tree blooms were a hit, but so were the numerous flowers in the

"lawn." Everyone loves dandelions and I also saw quite a bit of

activity around the purple dead nettles. (This guy is a

bumblebee, although I didn't brush up on my bumblebee

identification

enough to figure out his full name. Below is some sort of fly and

what might be a miner

bee.)

Fruit

tree blooms were a hit, but so were the numerous flowers in the

"lawn." Everyone loves dandelions and I also saw quite a bit of

activity around the purple dead nettles. (This guy is a

bumblebee, although I didn't brush up on my bumblebee

identification

enough to figure out his full name. Below is some sort of fly and

what might be a miner

bee.)

Nature never acts quite

the way you'd suspect, so I wasn't entirely surprised to see the

largest congregation of bees...on the manure pile! I knew that

butterflies visit manure to suck up salts (and there were both

butterflies and moths present), but I didn't realize that bees were

equally interested. Our honeybees turned up their noses at the

composted excrement, but there were at least fifty of these small bees

(miner bees again?) on the manure, along with a couple of greater

bee flies and hover

flies.

I'm glad to see that our

pollinator population is so diverse and healthy! Too bad some of

the trees they're pollinating got ahead of themselves and bloomed all

the way out before Saturday night's 27 degree freeze. I expect

moderate damage to the full-bloomed pears, barely blooming cherry, and precocious nectarine, and hardly any damage at all to the kitchen peach who valiantly held her horses until the freeze watch was past. Great job, kitchen peach!

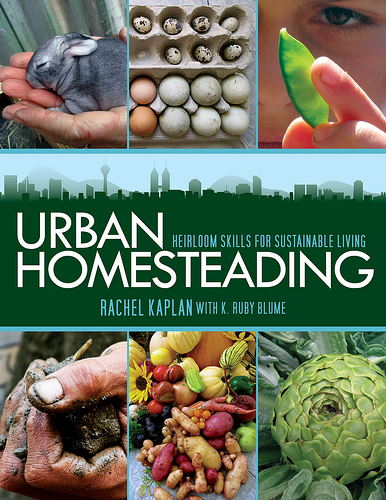

Urban Homesteading, by Rachel Kaplan with K.

Ruby Blume, is a breath of fresh air in the usually stuffy room of

gardening and homesteading literature. Don't get me wrong --- I

adore books by Paul Stamets, Steve Solomon, and others, but these texts

tend to be written by, for, and about middle class, white, straight

people. Urban

Homesteading

highlights ideas that are applicable to everyone, and the stunning

photos in the book back that theme up.

Urban Homesteading, by Rachel Kaplan with K.

Ruby Blume, is a breath of fresh air in the usually stuffy room of

gardening and homesteading literature. Don't get me wrong --- I

adore books by Paul Stamets, Steve Solomon, and others, but these texts

tend to be written by, for, and about middle class, white, straight

people. Urban

Homesteading

highlights ideas that are applicable to everyone, and the stunning

photos in the book back that theme up.

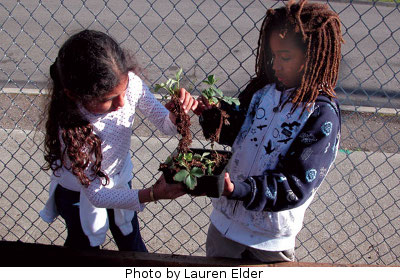

The case studies

sprinkled throughout Urban

Homesteading are

part of what gives this book such a rich flavor. For example, the

authors highlight Spiral Gardens, a non-profit that brings

gardening and fresh food into a low-income community in Berkeley where

lack of access to fruits and vegetables leads directly to shortened

lifespans. Reading Rachel Kaplan's book reminds me that there is

a social justice element to growing your own food that we often forget

in our middle class bubble. Can you imagine living in a place

where you can't get perishables without driving and can't afford to

drive? Of course growing your own is the answer!

I don't want you to think the

book is preachy or dense, though. Instead, Urban

Homesteading is

an easy to read introduction to dozens of topics that every beginning

homesteader is interested in, all told with an urban flare. And

the book is worth reading just for the artwork --- stunning photos of

dozens of urban homesteads and homesteaders interspersed between

original artwork by K. Ruby Blume. This is the perfect book for a

budding urban homesteader to pore over

for ideas, or for the established homesteader to put on her coffee

table (if she has one) to subtly influence more mainstream guests.

I don't want you to think the

book is preachy or dense, though. Instead, Urban

Homesteading is

an easy to read introduction to dozens of topics that every beginning

homesteader is interested in, all told with an urban flare. And

the book is worth reading just for the artwork --- stunning photos of

dozens of urban homesteads and homesteaders interspersed between

original artwork by K. Ruby Blume. This is the perfect book for a

budding urban homesteader to pore over

for ideas, or for the established homesteader to put on her coffee

table (if she has one) to subtly influence more mainstream guests.

(In the interest of full

disclosure, I should tell you that Rachel Kaplan let me download a

pre-release version of the ebook to review, but I have to admit that I

didn't expect the book to be half as good as it is!)

| This post is part of our Urban Homesteading lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The last

time I checked in on our bees, they had started raising a

bit of brood, but this time the nursery was much bigger. Baby

bees of all ages lined three frames, adding up to a total of two full

frames of brood if you merged them all together.

The last

time I checked in on our bees, they had started raising a

bit of brood, but this time the nursery was much bigger. Baby

bees of all ages lined three frames, adding up to a total of two full

frames of brood if you merged them all together.

I'm impatiently waiting

until our hive has six frames of brood, which is the bare minimum

needed to split

a hive the easy way

without hunting down the queen. Although it took a month for the

hive to build up from half a frame to two frames of brood, I suspect

the colony might reach the splitting threshold in just a few weeks now

that the wildflowers, fruit trees, and garden weeds are all in full

bloom. Nectar flows usually tempt queens to lay faster, and we're

in the midst of one heck of a nectar (and pollen) flow.

Have you ever tried to explain to a mainstream

American why you homestead? The conversation often goes something

like this:

Have you ever tried to explain to a mainstream

American why you homestead? The conversation often goes something

like this:

Mainstream American:

"Okay, now explain to me again why you put so much effort into growing

tomatoes. Did you know they're less than a dollar a pound at Food

City?"

Me: "Yuck! We

can't even eat storebought tomatoes any more. A sun-warmed,

organic tomato picked straight off the vine is so delicious..."

My eyes mist over and I start counting the days until our summer garden

is in fruit again.

Mainstream American

(snapping her fingers impatiently): "Hello!? Are you still

there? Did you mention something about me not being able to use

an indoors shower when I visit you?!!!"

Me: "Yeah, we haven't

gotten around to that yet. The garden and orchard just seem more

important right now."

Mainstream American: "So

hire somebody to install one. Duh!"

Me: "I'd rather wait a

few years until we have time to do it ourselves. I don't think

it's worthwhile to work 40 hours a week outside the home so that we can

have modern conveniences."

Mainstream American

(frantically trying to change the subject away from homesteading): "Did

you see that cool car commerical in the Super Bowl last night."

Me: "Super Bowl?

Is that baseball?"

Which is all a far too long way of saying that

one of my favorite parts of Rachel Kaplan's Urban Homesteading was her explanation of why

she thinks homesteading is important. Rachel writes that people

considering homesteading for the first time often think about what

they'd lose in the endeavor, but that

the homesteading

lifestyle isn't about what you do without, but what you gain. As

a result of living more simply, we have more time with people who

really matter and our souls (and bodies) are nourished by being part of

the ecosystem. We're more self-sufficient, so losing a job isn't

a disaster and we know how to rebuild after a fire or hurricane.

And, of course, there's a deep satisfaction involved in making things

with your own two hands.

Which is all a far too long way of saying that

one of my favorite parts of Rachel Kaplan's Urban Homesteading was her explanation of why

she thinks homesteading is important. Rachel writes that people

considering homesteading for the first time often think about what

they'd lose in the endeavor, but that

the homesteading

lifestyle isn't about what you do without, but what you gain. As

a result of living more simply, we have more time with people who

really matter and our souls (and bodies) are nourished by being part of

the ecosystem. We're more self-sufficient, so losing a job isn't

a disaster and we know how to rebuild after a fire or hurricane.

And, of course, there's a deep satisfaction involved in making things

with your own two hands.

That said, Rachel

explains that she's not seeking self-sufficiency but community

sufficiency, achieved by building guilds of people (and plants,

animals, fungi, and bacteria) who fill all of the niches in her

community. Her

book considers the big picture right from the beginning, looking at

social justice and peak oil as ethical reasons to homestead that

transcend the personal.

I'd be curious to hear

what your own goals and beliefs about

homesteading are. Do you homestead to be prepared for the

apocalypse? Because you don't want to get a job? Because

you're enthralled by the beauty of a garden in full leaf? What do

you say when that mainstream American tries to understand your life

choices?

| This post is part of our Urban Homesteading lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

These oversized bags are good

for keeping things safe and dry, but you can carry more boxes by

wrapping them together with some rope.

I

consider stump

dirt to be a miracle

planting aid. But what is it?

I

consider stump

dirt to be a miracle

planting aid. But what is it?

The obvious answer is

--- that moist, dark, earthy-smelling organic matter found inside

decaying trees or logs. Different trees create stump dirt of

varying quality; my favorite source by far is our ancient hollow beech

halfway up

the hillside, while box-elders product lower grade stump dirt.

Maybe hardwood stump dirt is better than softwood?

The analytical side of

me started nibbling away at what stump dirt actually is a few weeks

ago, and the best idea I've come up with is that stump dirt is pure

organic matter created when fungi decompose wood. The closest

mainstream garden ingredient I could find is mushroom compost, but that

is the result of fungi growing on higher nitrogen substrates like straw

and manure, so any comparisons should be taken with a grain of

salt. One study of mainstream mushroom compost showed that it

consisted of:

- 28% organic matter and 58% moisture

- 1.12% nitrogen, 0.67% phosphate, and 1.24% potatssium (aka NPK of

1.12-0.67-1.24)

- 2.29% calcium, 0.35% magnesium, and 1.07% iron

- C:N ratio of 13:1

Naysayers on the internet

report much lower NPK values for mushroom compost, though --- closer to

0.7-0.3-0.3 --- and I suspect our stump dirt is at the lower end of the

fertilizing spectrum. That would explain why the garden beds I

treated with stump dirt last year didn't show much growth --- stump

dirt isn't a replacement for compost. Instead, it makes a great

ready-made potting soil and can also be used like peat moss to fluff up

organic-matter-poor soil. If we ever had enough to apply stump

dirt to our garden in large quantities, I suspect it would act a bit

like biochar, providing spots for

microorganisms to grow unhindered. And stump dirt from

deep-rooted forest trees is probably even higher in micronutrients than the analysis above

portrays.

Naysayers on the internet

report much lower NPK values for mushroom compost, though --- closer to

0.7-0.3-0.3 --- and I suspect our stump dirt is at the lower end of the

fertilizing spectrum. That would explain why the garden beds I

treated with stump dirt last year didn't show much growth --- stump

dirt isn't a replacement for compost. Instead, it makes a great

ready-made potting soil and can also be used like peat moss to fluff up

organic-matter-poor soil. If we ever had enough to apply stump

dirt to our garden in large quantities, I suspect it would act a bit

like biochar, providing spots for

microorganisms to grow unhindered. And stump dirt from

deep-rooted forest trees is probably even higher in micronutrients than the analysis above

portrays.

All of that said, you

can't buy stump dirt, and you only find it in middle-aged to old

forests. I mine a couple of five gallon buckets every year out of

our beech tree, but save it for extra-special occasions. Another

reason to have a mature woodlot on your property, perhaps?

I

have to admit that I've been guilty of thinking of urban homesteading

as homesteading lite in the past, but Rachel Kaplan's Urban

Homesteading

helped me realize that the city version is not just a subgenre, but is

instead an endeavor with just as much potential as rural

homesteading. I was struck by the way Rachel's book introduced

all of the topics you'd expect to find in an intro to homesteading, but

took the specifics of city life into account. Below, I've listed

just a few of the ways that her advice differs from that found in rural

homsteading tomes.

I

have to admit that I've been guilty of thinking of urban homesteading

as homesteading lite in the past, but Rachel Kaplan's Urban

Homesteading

helped me realize that the city version is not just a subgenre, but is

instead an endeavor with just as much potential as rural

homesteading. I was struck by the way Rachel's book introduced

all of the topics you'd expect to find in an intro to homesteading, but

took the specifics of city life into account. Below, I've listed

just a few of the ways that her advice differs from that found in rural

homsteading tomes.

- Gardening --- In addition

to a section about how to find space to grow food in the city (which I

thought was so important it's going to make up its own post), Urban Homesteading

gives tips on making a seed ball to use in guerilla gardening and

building self-watering planters out of used materials. Espaliers

are another good choice for fitting lots of fruit trees in a city

backyard.

- Livestock --- In the

city, animals need to be small and, most of all, quiet. Compost worms, honey bees, chickens, and

rabbits are Rachel's top picks, followed by quail, ducks, and

goats. I'd never seen quail

on a top livestock list before, but Rachel explains that Japanese quail

(aka coturnix) can live in a very small space, produce eggs when less

than two months old, lay daily for at least a year, and require only

67% as much feed to produce a pound of eggs as chickens do.

- Utilizing waste --- One

of the few things I envy about city life is the amount of biomass free

for the taking. Rachel gives a recipe for making "Berkeley

compost" out of used coffee grounds, and I know from my own experience

that fallen leaves, grass clippings, and even bales of straw (leftover

from Halloween decorations) are often easy to find during trash pickup

day in the city. If you're building a structure or renovating

your existing house, discarded building supplies are also easy to come

by.

- Stocking up on food ---

In addition to all the usual advice about canning and fermenting, Urban Homesteading challenges

you to find ways to glean forgotten produce from the city. Many

people ignore the fruit that drops from their trees and will be glad

for you to come clean the apples or pears out of their yard.

- Legalities --- The downside of city living (from my point of view, at least) is the fact that you have to toe the line about number of livestock, permits, and so forth.

With the American

population so concentrated in our cities, it's essential that we find

ways to let urbanites join in the homesteading fun. Rachel

Kaplan's book gives lots of great tips to help city dwellers head in

that direction.

With the American

population so concentrated in our cities, it's essential that we find

ways to let urbanites join in the homesteading fun. Rachel

Kaplan's book gives lots of great tips to help city dwellers head in

that direction.

| This post is part of our Urban Homesteading lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I think five gallons is a

good start for our first do it yourself solar shower.

For the longest time I had a

50 gallon solar barrel image in my mind, but finally realized we didn't

need nearly that much volume, and 5 gallons might warm up faster.

April is a weeding

month. It's essential to get the small perennials weeded before

they really start growing so that I don't damage their new shoots and

flowers, so this week's goal is to weed the strawberries, asparagus,

rhubarb, herbs, perennial onions, and garlic.

April is a weeding

month. It's essential to get the small perennials weeded before

they really start growing so that I don't damage their new shoots and

flowers, so this week's goal is to weed the strawberries, asparagus,

rhubarb, herbs, perennial onions, and garlic.

Next week, I'll focus on

the beds to be transplanted or planted into this month, then will move

on to the beds earmarked for summer crops. Last call (if I don't

run out of time before planting season begins) will be weeding the

spring garden that I planted in February and March.

A winter mulch of straw makes this weeding job less

time-consuming, but there's still plenty of chickweed, bittercress,

dandelions, and dead nettles pushing up through my mulch. Every

year, I get a bit further ahead of the weeds --- maybe this year will

be the one where I'll rip all of the spring weeds out before they go to

seed.

The task looks a bit

daunting, but feels better once I dive in and begin. Twenty-six

beds later, I feel as peaceful as if I'd spent the day meditating, and

the chickens are sated on three wheelbarrow loads of worms, snails, and

chickweed. I think April is going to be a good month.

Suburbanites can turn their

lawns into vegetable gardens, but how do real city-dwellers find space

to homestead? Rachel Kaplan gives you several ideas to

choose from, such as...

Suburbanites can turn their

lawns into vegetable gardens, but how do real city-dwellers find space

to homestead? Rachel Kaplan gives you several ideas to

choose from, such as...

- Fill up your own soil first, of course.

- Then ask your neighbor if you can turn their yard into a garden. If you share the bounty, they're bound to say yes, and may become a gardening convert.

- Container gardening works on balconies, roofs, and any other spot with a bit of sun.

- Tear up unused concrete and

asphalt. The photo above shows how a small driveway can

turn into a vibrant garden. Rachel's book gives tips on the best

tools and tricks to use during pavement demolition.

- Sign up for a plot in the local community garden.

- Look for abandoned lots, find out who owns then, and see if you can get permission to turn the ground into a garden. (Or guerrilla garden on the sly.)

Rachel

includes an inspiring map of her personal "walking gardens." In

addition to filling up her own yard, she grows vegetables in another

yard with the owner, keeps bees and chickens in a third and fourth

yard, and has a plot at the community garden. Now that's what I

call hunting and gathering!

Rachel

includes an inspiring map of her personal "walking gardens." In

addition to filling up her own yard, she grows vegetables in another

yard with the owner, keeps bees and chickens in a third and fourth

yard, and has a plot at the community garden. Now that's what I

call hunting and gathering!

While you're doing your

rounds, don't forget to scope out sources of garden fertility.

I'm imagining setting out for my daily walk with the yellow wagon and

coming home with a bag of leaves from the curb, some food scraps from a

restaurant to go in the worm bin, and of course an armful of produce

for dinner. Almost makes me want to live in the city!

| This post is part of our Urban Homesteading lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Look up the part#....which is 176556, pay 11 dollars plus shipping, and wait.

I

eased into cooking with meat by buying it ground, but have since been

branching out into using more and more of the whole animal.

Growing

our own broilers

trained me to use every bit of a chicken, and

now that we've bought a whole

lamb, I've been

doing the same with red

meat. It turns out that there are five main categories:

I

eased into cooking with meat by buying it ground, but have since been

branching out into using more and more of the whole animal.

Growing

our own broilers

trained me to use every bit of a chicken, and

now that we've bought a whole

lamb, I've been

doing the same with red

meat. It turns out that there are five main categories:

Ground

meat is the

easiest to cook with since you can make it into

burgers, sausage, or use it any other way you'd use hamburger or ground

turkey.

If I hadn't asked for the front legs of our lamb to be ground up, there

wouldn't

have been much ground meat, though, mostly from the belly.

Steaks are cuts that are tender

enough to fry or grill and eat with a knife and fork. Both chops and sirloin can be cooked as steaks,

with the latter being a bit more tender. Our pastured lamb

growers recommend searing lamb steaks over medium-high heat then

finishing up cooking at a lower temperature, which worked great for us.

Roasts are cuts that are a bit

tough to be fried up and should instead be either stewed over low heat

or baked in a cool oven for an hour or more. Letting them

marinate first  in an acidic marinate like

tomatoes or wine can also help tenderize the meat. Legs are the hind legs, cut whole

and looking a bit like a ham. Shanks are the upper arm (front

leg). Riblets are half bone and half fat

and meat --- they're the only part that I'm a bit at a loss about how

to cook.

in an acidic marinate like

tomatoes or wine can also help tenderize the meat. Legs are the hind legs, cut whole

and looking a bit like a ham. Shanks are the upper arm (front

leg). Riblets are half bone and half fat

and meat --- they're the only part that I'm a bit at a loss about how

to cook.

Bones won't come with your lamb

unless you specifically ask for them,

but you should! Bones make a wonderful broth, boiled for several

hours in a pot of water. The remains can be fed to your dog.

Heart

and liver are

cooked like any other organ meat. I sometimes

cook these up into broth, very occasionally fry up a liver for Mark,

and sometimes give the organs to the cats and dog as a health boost.

Once you learn to cook

meat in each of these categories, you'll be ready to cook nearly the

whole animal of just about every type of livestock out there.

With chickens, the meat type is more a factor of age than cut, but it's

still good to know how to grind or stew up old birds and to make broth

out of the bones. Even if you're not buying a whole animal,

cooking with unusual cuts allows you to buy cheaper meat that is just

as good for you, and to respect the meat animal by not tossing less

tender parts of their body.

I'm

sure several of you are interested to hear Rachel Kaplan's take on the

Dervaes' attempt to protect their trademark on the term "urban

homesteading."

Since she's written a book by that name, I figured Rachel had been

contacted by the Dervaes family, and I was right. She emailed:

I'm

sure several of you are interested to hear Rachel Kaplan's take on the

Dervaes' attempt to protect their trademark on the term "urban

homesteading."

Since she's written a book by that name, I figured Rachel had been

contacted by the Dervaes family, and I was right. She emailed:

Our publisher is working on the legal front with all of this right now, and hasn't even disclosed to us his strategy, but he (and we) and everyone we know feels strongly that urban homesteading is a cultural movement owned by the many, and not the few, and that the Dervaes' claim is lacking in merit. We are continuing our work in the world, and of course the publication of the book, on which we have worked so hard.

We believe this has even become the issue it is because this is a cultural movement--so many people are interested and involved in this. We are hoping for an amicable resolution to the struggle, but it remains to be seen how the whole thing plays out.

After our own experience seeing the diversity of people interested in homesteading topics at the Organic Grower's School, I have to agree with her. I hope that the themes become so mainstream that the Dervaes family has no hopes of maintaining control over the term "urban homesteading."

Our $2 ebook shows you how to create your

own job so you have time to homestead.

| This post is part of our Urban Homesteading lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The worm bin

has been having a problem with unwanted visitors.

The worm bin

has been having a problem with unwanted visitors.

My solution for today was to

add a 2x4 and some pieces of appearance board to the frame and part of

the lid.

I'll know by next week if

it's working, or if I need to take the worm bin armour level up a notch.

If we build another one I

think we'll design the lid to have a slope and maybe attach some shower

board to the plywood surface.

Over

the years, I've learned that putting tomato seeds in a cold frame (or,

this year, a quick

hoop) in early April

results in sets that are smaller than those started inside but more

ready to hit the ground running when it comes time to transplant them

into the garden in mid May. It sounds counterintuitive --- start

with smaller plants, end up with more tomatoes --- but my cold frame

seedlings tend to have more roots and to be healthier than seedlings

started in flats indoors.

Over

the years, I've learned that putting tomato seeds in a cold frame (or,

this year, a quick

hoop) in early April

results in sets that are smaller than those started inside but more

ready to hit the ground running when it comes time to transplant them

into the garden in mid May. It sounds counterintuitive --- start

with smaller plants, end up with more tomatoes --- but my cold frame

seedlings tend to have more roots and to be healthier than seedlings

started in flats indoors.

Cold frame tomatoes

don't send up leaves until mid to late April, so they never get

leggy and aren't exposed to any low temperatures that can stunt their

growth. During the years that I started tomatoes indoors, I often

ended up with plants that grew slowly even once I put them out in the

garden since night-time temperatures in the trailer in April can easily

drop down into the thirties or forties, doing long term damage to the  tender

seedlings. If your tomato seedlings have a purplish cast to their

leaves, they've been stunted by cold weather.

tender

seedlings. If your tomato seedlings have a purplish cast to their

leaves, they've been stunted by cold weather.

The only really hard

part about starting tomatoes in a cold frame is hearing from your

friends about how they started tomatoes two weeks ago, and not giving

in to peer

pressure. I

just remind myself that my method not only works better, it's also less

work and requires no electricity, and I manage to hold firm until the

soil temperature reaches 50 degrees. For future reference,

asparagus shoots up at the same temperature tomato seeds need for

germination, so I won't need to relentlessly check soil temperature

next year. (And, look, asparagus!!)

It would seem that our spurt

of springtime sunshine wasn't quite enough energy to heat up my 5

gallon bucket solar shower

to any noticeable warmth.

The next stage of the

experiment involves a small 2-15 gallon submersible aquarium heater

which can be found for around 15 dollars at local retail outlets. It

automatically warms your water to a 76 to 80 degree range, but you need

to give it a full 24 hours to reach that temperature.

Installing

the heater was easy thanks to the attached suction cup and it didn't

take much effort at all to wrap some reflectix around the sides and the

top to hold the heat in.

Installing

the heater was easy thanks to the attached suction cup and it didn't

take much effort at all to wrap some reflectix around the sides and the

top to hold the heat in.

I plugged in a Kill-a-Watt

device to measure how much power it will need. Anna thinks it might be

comparable to heating up a pot of water on the electric stove, which is

just the sort of debate we got the Kill-a-Watt gizmo for. The heater is only

rated at 50 watts, which might be less power at 24 hours compared to 5

minutes of a 220 volt stove top coil.

Five

years ago, I went hog-wild and started about 35 different types of

tomatoes. Every year since then, I've been whittling our

selection down to the varieties that taste the best, produce the most,

and are least blight-prone. Here are the eight varieties we'll be

growing in 2011:

Five

years ago, I went hog-wild and started about 35 different types of

tomatoes. Every year since then, I've been whittling our

selection down to the varieties that taste the best, produce the most,

and are least blight-prone. Here are the eight varieties we'll be

growing in 2011:

- Martino's roma ---

delicious and a copious fruiter. Was more

resistant to the blight than our other roma varieties (San Rodorta and

Russian), partly because the

vine is a bit less vigorous.

- Yellow

roma --- mixes with Martino's roma to make a very unique

sauce.

The vine grows like crazy, so it has to be pruned a lot, and the fruits

do tend to crack on top, so they require a bit more preparation than

Martino's roma.

- Ken's red --- an un-named

but delicious big, red slicing tomato that we got from my friend Ken.

- Japanese black trifele --- this was given to me as "Brandywine", but the fruits are shaped like a drop of water and a search of the internet suggests my tomato is actually Japanese black trifele. Purple slicing tomato with great taste, although you have to cut off a woody top part.

- Blondkopfchen --- extremely productive, small yellow tommy-toe.

Stupice

--- red slicing tomato that's just a bit larger than the biggest

tommy-toes. Our

earliest tomato to ripen, listed at 52 days.

Stupice

--- red slicing tomato that's just a bit larger than the biggest

tommy-toes. Our

earliest tomato to ripen, listed at 52 days.

- Early Pick --- another

red slicing tomato that's very early.

- Crazy --- large, red tommy-toe that produces nearly as early as Stupice. Somewhat blight resistant.

We grow one plant each

of the last six varieties for eating in the summer and about

twenty-five romas

to keep us in spaghetti sauce, pizza sauce, ketchup, and dried

tomatoes

all year. I had actually forgotten which tomato varieties I

wanted to focus on this year, so I was very glad I'd made notes on my

seed-packets when I packaged up the summer's seeds!

The 50 watt aquarium heater

didn't seem to add much heat at all to the 5

gallon bucket solar shower set up.

I gave it about 20 hours and

decided to give up on this being a low tech way of heating up a small

amount of water.

My next approach could be

something more conventional, but I've got another low tech idea that

needs to see the light of day to satisfy my curiosity.

I could write about how

we baked up some of the last homegrown roots along with a leg of lamb,

salad, and a lemon meringue pie for a true spring feast. How we

had a centerpiece of lilac and other spring flowers, and a roaring

creek for background music. But then you'd think Joey's birthday

party was peaceful.

It wasn't. Mom and

Maggie made a homemade pinata and after we'd stuffed ourselves, we got

down to fun and games. I tied a string to a stick and threw it

over a branch...

...then hoisted the

pinata aloft.

As the birthday boy,

Joey got to go first. I tied on his blindfold, enjoying my place

of power atop the picnic table. (Yes, I am the shortest person in

my family.)

We each gave it a try.

"No, Anna, it's over

there!"

Then Joey got smart and

ditched the plastic bat and picked up a branch. Whack!

Whack! Whack!

We were laughing so hard

we could hardly pick up the baggies of dried dates, cashews and other

treats.

Thanks for the great

party, everybody!

Our

lunchtime series will be going on summer vacation starting this week

--- the winter is over and I'm itching to be outside doing (or at least

napping under the peach tree) rather than indoors pondering.

There may be a few series sprinkled through the summer, but they'll be

erratic until cold weather sends me back to my books.

Our

lunchtime series will be going on summer vacation starting this week

--- the winter is over and I'm itching to be outside doing (or at least

napping under the peach tree) rather than indoors pondering.

There may be a few series sprinkled through the summer, but they'll be

erratic until cold weather sends me back to my books.

For those of you who go

into withdrawal with only two posts from us per day, why not check out

some of our other blogs?

- Our chicken blog

is my favorite spot for rambling at length about chicken pastures,

chicken behavior, and more. I also post updates and tips about

our chicken waterer there.

- Our deer deterrent blog is Mark's inventing website --- those of you who get a kick out of his ability to make something from nothing will really enjoy it. And, of course, you can learn some great tips about keeping deer out of your garden.

Wetknee

is where I post longer musings on living simply and making a living

with an internet business.

I also include updates about our ebooks over there, so be sure to

subscribe if you want to know as soon as ebooks are ready.

Wetknee

is where I post longer musings on living simply and making a living

with an internet business.

I also include updates about our ebooks over there, so be sure to

subscribe if you want to know as soon as ebooks are ready.- Cosmic cookout is

where Mark ponders or debunks conspiracy theories, the physics of

consciousness, and the disclosure movement.

- Clinchtrails is where I post photographs that are too pretty not to share but that don't fit in any post, along with bits and pieces about natural history and trips.

Stay tuned for

tomorrow's lunchtime post to explain the exciting side of lunchtime

series being on vacation!

It only takes a few minutes

to install

a new engine cable.

I had to break a plastic

fastener to get the old cable off and decided some electrical tape was

good enough to secure it to the support handle.

Let the spring/summer mowing

fun begin!

I

took the fabric off all of the quick

hoops except the tomato

bed

Saturday because the heat was starting to make the lettuce turn a bit

bitter (and I wanted the plants to capture every raindrop from the

weekend's thunderstorms.) I'll probably re-cover the beds tonight

and leave them protected for a while since the weather is supposed to

return to 30s to 60s rather than the recent 50s to 80s.

I

took the fabric off all of the quick

hoops except the tomato

bed

Saturday because the heat was starting to make the lettuce turn a bit

bitter (and I wanted the plants to capture every raindrop from the

weekend's thunderstorms.) I'll probably re-cover the beds tonight

and leave them protected for a while since the weather is supposed to

return to 30s to 60s rather than the recent 50s to 80s.

I

was intrigued to see the differences between onion seedlings planted

at various times, and places: inside, under quick hoops, and

unprotected outside. As you might expect, the onions started

earliest inside then transplanted under the row covers are tallest,

followed by the earliest plants direct-seeded into quick hoops, then by

later plants direct-seeded into quick hoops. The onions seeded

directly into unprotected ground once the soil temperature reached 35

degrees are smallest, but they've all germinated in good

numbers and I suspect the head start given by the row covers won't make

much difference in the long run. I'll let you know if I can still

see effects of

the various planting schedules at harvest time, but since onions aren't

a crop I need to rush to the table, I may plan to use the quick hoops

for something else next spring.

I

was intrigued to see the differences between onion seedlings planted

at various times, and places: inside, under quick hoops, and

unprotected outside. As you might expect, the onions started

earliest inside then transplanted under the row covers are tallest,

followed by the earliest plants direct-seeded into quick hoops, then by

later plants direct-seeded into quick hoops. The onions seeded

directly into unprotected ground once the soil temperature reached 35

degrees are smallest, but they've all germinated in good

numbers and I suspect the head start given by the row covers won't make

much difference in the long run. I'll let you know if I can still

see effects of

the various planting schedules at harvest time, but since onions aren't

a crop I need to rush to the table, I may plan to use the quick hoops

for something else next spring.

Something

like greens, maybe. Asian greens (above) and volunteer mustard

are nearly big enough to eat, and the swiss chard started in a quick

hoop already has two true leaves. We've had a couple of meals of

overwintered kale and mustard greens, but with only four plants

surviving, we're ready for a big mess of fresh greens. Maybe in a

week or so?

overwintered kale and mustard greens, but with only four plants

surviving, we're ready for a big mess of fresh greens. Maybe in a

week or so?

Last

year at this time, we'd already planted out our broccoli and cabbages,

but the seedlings are still a bit small for transplanting. It's

tough to tell whether a cold frame would have made these crucifers come

up sooner than the quick hoops did --- the asparagus was earlier last

year

too, which makes me think that the soil just took a bit

longer to warm up this spring than last.

The mule garden is

starting to feel full and vibrant again with all of this new

growth. Time to mow the aisles and dream of big harvests!

My real reason for putting

the lunchtime series on hold so early this

year is that a week of weeding cleared my mind enough that I realized I

had six

ebook ideas

and I wanted to give myself time to work on them. With so many ideas, I

don't quite know where to start, so I was hoping you'd chime in with a

comment to let me know which of these top three would float your boat:

My real reason for putting

the lunchtime series on hold so early this

year is that a week of weeding cleared my mind enough that I realized I

had six

ebook ideas

and I wanted to give myself time to work on them. With so many ideas, I

don't quite know where to start, so I was hoping you'd chime in with a

comment to let me know which of these top three would float your boat:

- The Short, Sweet, and

Self-sufficient Guide to Growing Backyard Mushrooms. When Cat

emailed me a few weeks ago to see if I would write an introductory post

to growing edible mushrooms for her blog, I realized that the bits and

pieces of information I've presented over here don't really make a

coherent whole. I tend to send people to books by Paul Stamets

when they ask me for advice about getting started with mushrooms,

but his books (although inspiring) make the process seem a lot

more difficult than it really is. I'm thinking of a short (maybe

20 to 40 page) ebook giving a brief explanation of mushroom biology,

telling which species are easy to grow, introducing the simplest

methods of growing them, and then covering home propagation. My

focus would be on tasty, cheap, and simple.

- Chickens in Permaculture. I don't really feel like I'm ready to write a definitive book about chickens in permaculture, but the great thing about ebooks is that you can put together the best information currently available, sell it for 99 cents so that lots of people will get inspired and start experimenting, then revise it later. I'm envisioning this ebook being as short as the mushroom one and talking about the pros and cons of pastures, tractors, and deep bedding, which plants you can grow to feed your flock, other alternatives for making your own chicken feed, and types of chickens to consider when starting a self-sufficient flock.

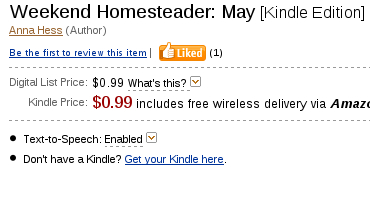

- The Weekend Homesteader

--- Darren

had the great idea of writing an ebook full of short projects that

people can use to dip their toes into the vast ocean of homesteading

without getting overwhelmed. I stole his idea and Mark and I soon

came up with a series of projects that would walk a beginner through

planting their first lettuce bed, making an under-the-sink worm bin,

scrounging supplies at the dump, and much more. This ebook would

be longer than the previous two and geared toward a generalized

beginner rather than than to the more experienced homsteader.

One

of my goals with focusing on ebooks rather than on lunchtime series

this summer is to reach more potential homesteaders. I adore

preaching to my choir, but my father pointed out that if I put ebooks

up on Amazon for 99 cents, I'll find lots of new readers who might not

have considered the homesteading lifestyle before they downloaded my

ebook.

One

of my goals with focusing on ebooks rather than on lunchtime series

this summer is to reach more potential homesteaders. I adore

preaching to my choir, but my father pointed out that if I put ebooks

up on Amazon for 99 cents, I'll find lots of new readers who might not

have considered the homesteading lifestyle before they downloaded my

ebook.

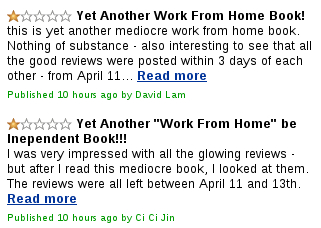

With that in mind, I

hope I can ask you for another favor. We

currently have two ebooks up on Amazon, and although some random folks

have found them, no one has left a review on either. If you've

bought Microbusiness

Independence

from us, please consider dropping by to leave a review. And, if

you're into butchering chickens, perhaps you'll consider our newly

updated Eating

the Working Chicken

ebook,

complete with dozens of photos to walk you through the entire process

from coop to table. I really appreciate you taking the time to

help me with my ebook project!

Every year, I tweak my method

of growing sweet potato slips. Year 1, we put sweet potatoes in

partially filled glasses of water and they rotted, so year 2 we

added a heat mat under the glasses. The heat mat tempted

several of the sweet potatoes to sprout, but I was disappointed at how

late the slips showed up --- we didn't fill the last of our sweet

potato beds until early July. So, last year, I

started the slips at the end of March...and the roots sat there

until April, producing slips during the same time frame as they had the

year before. I also lost several tubers last year since I chose

big roots that were less inclined to sprout.

Every year, I tweak my method

of growing sweet potato slips. Year 1, we put sweet potatoes in

partially filled glasses of water and they rotted, so year 2 we

added a heat mat under the glasses. The heat mat tempted

several of the sweet potatoes to sprout, but I was disappointed at how

late the slips showed up --- we didn't fill the last of our sweet

potato beds until early July. So, last year, I

started the slips at the end of March...and the roots sat there

until April, producing slips during the same time frame as they had the

year before. I also lost several tubers last year since I chose

big roots that were less inclined to sprout.

This year, I made yet

more changes to my sweet potato propagation method. I chose

tubers that were about two inches in diameter at the widest point and

placed them beside the incubator for two weeks to

preheat. Monday, I dug about a gallon of small

gravel out of an eroded wash above the alligator swamp and filled up a

seed-starting flat, laying the sweet potatoes on their sides and then

packing damp gravel between them. I added the clear top on the

flat to keep the contents moist and slipped a heating pad underneath to

promote sprouting instead of rotting.

flat to keep the contents moist and slipped a heating pad underneath to

promote sprouting instead of rotting.

In case you're trying to

decide if sweet potatoes are worth growing, I'll throw some numbers out

there. Conventional wisdom, repeated all over the internet, holds

that white potatoes give you the most calories per acre, but in our

garden last year, we got just over 6 pounds of sweet potatoes per

garden bed, which comes to 2,379 calories. In contrast, we

harvested 6.5 pounds of white potatoes from each bed, but the white

potatoes have fewer calories per pound, so they lost the race at 2,034

calories per garden bed.

That said, the greatest

number of calories I've ever harvested from one

garden bed was a tie between a

bed yielding 13.5 pounds of carrots fall before last and the 3.5

cups

of amaranth seeds I threshed in the summer, both clocking in at just

over 2,500 calories. Clearly, white

potatoes aren't the only high calorie food you can grow in just a bit

of space. I wonder which other oft-repeated tidbits of gardening

lore aren't precisely correct? The moral of the story is --- try

several different kinds of high calorie crops and choose the ones that

match your soil, climate, and taste buds.

While I'm flooding you with

news updates, I thought I'd go ahead and mention that Walden Effect is

changing over to Branchable

as our new web host and blogging software this week. We're

excited to be using Joey's full feature blogging platform --- he

already saved the day last week by retrieving a post that I'd

accidentally deleted in February and reposting it with a backdate so

that it didn't clutter up the front page of the site. If you're

looking for a way to blog so that you're in control of your own data,

Branchable is the way to go.

While I'm flooding you with

news updates, I thought I'd go ahead and mention that Walden Effect is

changing over to Branchable

as our new web host and blogging software this week. We're

excited to be using Joey's full feature blogging platform --- he

already saved the day last week by retrieving a post that I'd

accidentally deleted in February and reposting it with a backdate so

that it didn't clutter up the front page of the site. If you're

looking for a way to blog so that you're in control of your own data,

Branchable is the way to go.

You probably won't

notice much different over here, but those of you

who read Walden Effect in an RSS reader will see a flood of old posts

when I do make the switch. And there's a slight possibility that

there will be some brief down time as I make the migration

happen. So, please bear with us!

We recently cut down this box

elder tree to make room for chicken pasture number 5 and thought the

stump would make a good home for our cardboard

propagated mycelium.

Making vertical

grooves took about half as much time compared

to drilling holes, and sealing it up

with bees wax was a bit easier thanks to the effect of gravity.

Now we wait and wait some

more. It might take a year or more for the first mushroom to pop out.

There's

an old saying that American Indians on the Plains used every part of

the buffalo. Although I'm aware that the saying is part of the Noble

Savage image and

might not be technically true, I still think it's a great analogy for

our goals as permaculture-inclined homesteaders. So when Mark cut

down a box-elder to make way for an everbearing

mulberry, I decided

to see how much of that tree we could use.

There's

an old saying that American Indians on the Plains used every part of

the buffalo. Although I'm aware that the saying is part of the Noble

Savage image and

might not be technically true, I still think it's a great analogy for

our goals as permaculture-inclined homesteaders. So when Mark cut

down a box-elder to make way for an everbearing

mulberry, I decided

to see how much of that tree we could use.

We cut three big logs

and used our

new gash method to inoculate them with homegrown oyster

mushroom spawn. Mark dug deep holes and dropped in the logs to

turn them into no-work mushroom

totems right there

in the moist shade of the floodplain. Then we set to work

inoculating the stump --- a way of taking advantage of even the roots

of the tree. Since we pass this spot twice a day while walking

Lucy, the resultant mushrooms won't go to waste.

The rest of the wood

will soon be cut into firewood for next winter. We've discovered

that box-elder makes perfect kindling, and is also all we need for most

of the winter to keep the well-insulated East Wing warm.

Finally,

I gathered up the big shreds of sawdust kicked up by the

chainsaw. Assuming I haven't let our

chicks die in the

shell with temperature variations, they're due to hatch this weekend

and will need some bedding for the few days they'll spend inside.

I'd been wondering what I'd use and was thrilled to see such prime wood

shavings.

Finally,

I gathered up the big shreds of sawdust kicked up by the

chainsaw. Assuming I haven't let our

chicks die in the

shell with temperature variations, they're due to hatch this weekend

and will need some bedding for the few days they'll spend inside.

I'd been wondering what I'd use and was thrilled to see such prime wood

shavings.

The only part of the

box-elder that is currently going to waste is the smallest

branches. I dragged them into a small brush pile, though, and

hope they'll rot down and turn into a breeding ground for worms and

other critters. Since the spot is inside a soon-to-be chicken

pasture, hopefully even that fertility will eventually wind its way

into our bellies.

Pure joy is gently uprooting

clods of sunlit earth housing young broccoli and cabbage seedlings,

then watering them into new beds while the flock scratches through the

compost pile next door. I could almost taste the crisply sweet

broccoli heads as I worked, and it was tough to make myself stop when

the requisite 50 plants (plus 7 cabbages) were in the ground.

Pure joy is gently uprooting

clods of sunlit earth housing young broccoli and cabbage seedlings,

then watering them into new beds while the flock scratches through the

compost pile next door. I could almost taste the crisply sweet

broccoli heads as I worked, and it was tough to make myself stop when

the requisite 50 plants (plus 7 cabbages) were in the ground.

Another couple dozen

sets still grace the quick hoop, but I want to keep them in reserve to

replace any seedlings that die in the next week. I've learned the

hard way that transplants are magnets for cut worms (I always lose a

few plants, but never enough to bother making each seedling a

protective collar), cat damage, and freak killing

frosts.  This year I waited a couple

of extra days until the 10 day weather forecast had lows all above

freezing, but you just can't trust the spring weather not to throw a

monkey wrench in the works for fun.

This year I waited a couple

of extra days until the 10 day weather forecast had lows all above

freezing, but you just can't trust the spring weather not to throw a

monkey wrench in the works for fun.

After I replace any dead

seedlings next week, the rest of my crucifer babies will be looking for

a home. Joey, Mom, this is your chance to add some crunch to your

spring garden! I may also tuck a few extras into the hugelkultur

donuts beyond the

canopy of my fruit trees and perhaps even transplant a few into the

soon-to-be vacated chicken pasture. After all, I learned last

year that broccoli leaves are one of our chickens' favorite foods.

Tilting up the old

boards I used to attach the chicken wire is like an instant buffet of

worms and bugs for our flock.

Part of my new routine when I

collect eggs in the evening is to lift a few of the boards up for a

minute or two while the chickens scratch and peck for fresh crawling

snacks.

It's got me thinking about

some sort of gizmo that lifts up a board or piece of cardboard long

enough to let the chickens forage.....maybe wait till nightfall to

reset it so that it can be ready to provide fresh worms and bugs the

next day.

In

the long run, tree fruits are the least work for the most food, but

they also take so darn long to produce! Due to a couple of years

learning about how to

plant trees in our waterlogged clay soil, we only ate our first tree

fruits --- peaches --- last summer. This year, we'll have more

peaches and maybe a pear, but it could be another couple of years

before we taste a homegrown apple.

In

the long run, tree fruits are the least work for the most food, but

they also take so darn long to produce! Due to a couple of years

learning about how to

plant trees in our waterlogged clay soil, we only ate our first tree

fruits --- peaches --- last summer. This year, we'll have more

peaches and maybe a pear, but it could be another couple of years

before we taste a homegrown apple.

Meanwhile, we've been

eating strawberries since our second year on the farm (and could have

eaten them less than a year after planting if we'd set

them out in late summer.) Our everbearing

red raspberry

fruited the first year we had it in the ground, and has since colonized

two more garden rows and our rabbiteye

blueberries also had a handful of fruits the first year. Thornless

blackberries fruited

copiously starting the second year and grapes had a few fruits the

first year (if you don't count the year they grew in the garden as hardwood

cuttings.) If

the photo above is any indication, it looks like our new gooseberries are going to be fruiting the

second year after planting too (which is a bit surprising since I put

them in the ground later than I should have and they had a hard summer.)

Which is all a long way of

saying --- don't put all of your fruit eggs in the tree basket.

Planting a few small fruits in your garden the first year ---

especially brambles and strawberries --- is a great way to keep

yourself from going crazy waiting for that apple tree to slowly

mature. (And, yes, this post really is just an excuse to show off

my strawberry and gooseberry flowers.)

Which is all a long way of

saying --- don't put all of your fruit eggs in the tree basket.

Planting a few small fruits in your garden the first year ---

especially brambles and strawberries --- is a great way to keep

yourself from going crazy waiting for that apple tree to slowly

mature. (And, yes, this post really is just an excuse to show off

my strawberry and gooseberry flowers.)

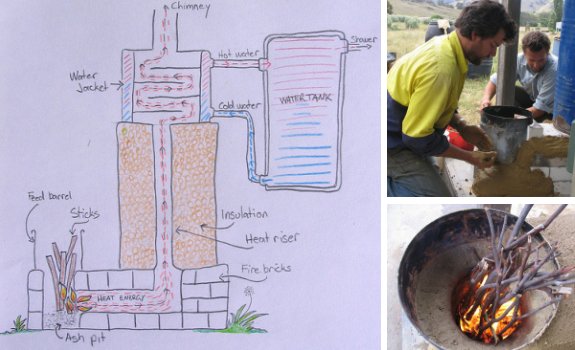

I appreciate all of the

alternative suggestions that readers have sent in concerning our solar

shower experiments and I especially liked the rocket stove shower

design by Milkwood.com

sent in by reader Sarah.

They built theirs in 2 days

and I'm guessing the cost to be around 200 to 400 dollars depending on

what type of materials you choose.

It's a bit complicated for

our current needs, but the idea has got me wondering if this could be

easily modified to handle some sort of hot water chicken dunking

station which might come in handy if the price of propane continues to

go up.

I am a nervous chicken

mother. For three weeks now, the kitchen thermometer has occupied

one of my central processors and I even had a nightmare that the heater

was running too hot (only to wake up and find that I was right.)

I've peered at the eggs, candled

them, topped off

their water, and, as of Friday, taken

out the egg turner and replaced it with a paper liner for hatching. Despite all that, I

didn't really believe we'd end up with a living chick. "If we

even get one," I promised myself, "it will be a success."

I am a nervous chicken

mother. For three weeks now, the kitchen thermometer has occupied

one of my central processors and I even had a nightmare that the heater

was running too hot (only to wake up and find that I was right.)

I've peered at the eggs, candled

them, topped off

their water, and, as of Friday, taken

out the egg turner and replaced it with a paper liner for hatching. Despite all that, I

didn't really believe we'd end up with a living chick. "If we

even get one," I promised myself, "it will be a success."

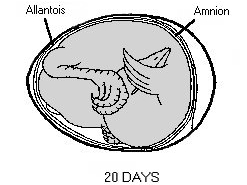

Twenty-one days will be

up today at 1 pm, and by Friday night I was starting to lose

faith. I'd read all kinds of reports on the internet of ways

chicks can die in the shell. Not only can I kill them if I let

the temperature get too hot or too cold (which I did a grand total of

four times), but the chicks could drown while trying to hatch if I kept

the incubator too humid. Shells that look porous when candled

(didn't I have one of those?) tend to let in bacteria and the chicks

die young, and then there's the question of whether our old hens are

even able to create a viable embryo at their advanced ages.

Then, Saturday

afternoon, I heard a strange bumping sound from the corner of the

kitchen. I pulled out the incubator and peered in to see that not

one but two eggs were rocking to and

fro. Someone was alive inside! Half an hour later, a third

egg joined the chorus, and at supper time egg number four chimed

in. Then, silence as the wearied chicks rested inside their hard

shells.

Today will be the big

day. Will we hatch live chicks? How many? Whose

eggs? So far, all three eggs laid by the young Golden Comet have

shown signs of life along with one of the eggs from the old

girls. No matter what happens, I plan to throw another batch of

eggs in as soon as the chicks are fully dry and ready to move to a

brooder --- if I can manage to keep at least 57% of my eggs alive to 20

days, this incubation experiment has merit. It's a good thing I

"planned" this hatch to coincide with a day of rest, because it's going

to take a team of mules to drag me away from my spectator role.

When our first

home grown chick showed

up he was already up and walking and we missed the break out drama.

Not so with chick 2.0.

He or she has made some

progress, but decided to rest at the half way point as of 5 minutes ago.

7 am on day 21 --- two

eggs are pipping. I knew the head developed on the blunt end of

the egg and somehow expected the first cracks to show up at that tip,

but both cracked areas are instead about a quarter of the way down the

shell.

The first signs of

pipping are exciting, but then...nothing happens. I wait, and

wait, and wait, nearly figuring the chicks died until I notice the

membrane below the cracked shell undulating as the chicks

breathe. Around lunchtime, the monotony is broken when one chick

gets inspired by the sound of Mark's voice and peeps up a storm.

2:25 pm --- One chick

has pecked

through the membrane and I can barely see a beak moving inside!

The

chick doesn't seem to be pecking at the shell so much as whacking its

whole face against the boundary of its miniscule world.

3 pm --- While I wasn't

looking, a third egg started pipping. But there's now no movement

from anything except the chick that showed off its beak half an hour

ago.

4 pm --- The most active

chick finally decides to get to work. Slowly but surely, it

knocks against the side of the egg, turning its head so that the crack

progresses around the egg's circumference. After 45 minutes, the

opening is half an inch long --- is this going to take all month?

4:45 pm --- Rest, who

needs rest? Suddenly, the chick is pecking like

mad. (I turn the incubator around and notice a fourth egg has

begun to pip.)

A thin line of blood

appears on the egg's membrane where the

chick scratched itself, but the little trooper keeps right on going.

One hard whack

rolls the egg over so that the chick's head is pounding against the

floor, at which point the youngster begins to push and strain against

the

three-quarters severed lid.

5:10 pm --- Plop! Out it falls onto the

floor of the incubator.

After all of that

commotion breaking out of the shell, you wouldn't have thought it would

take another half hour for the chick to figure out how to get its head

out of the lid.

A massive flapping of

incipient wings and the chick is free to drape itself across its

unhatched siblings. Two in-shell chicks join in the crazy peeping.

No signs of further chicks out of the shell this morning. Now I'll have to make the hard choice --- open up the incubator against everyone's advice and take out chick #1 and check on the chicks who haven't poked through yet, or leave them all another day?

See scads more cute chick photos (and learn how to become an expert at

incubation) in my 99 cent ebook.

Permaculture

Chicken: Incubation Handbook walks beginners through perfecting the

incubating and hatching process

so they can enjoy the exhilaration of the hatch without the angst of