archives for 02/2011

When I last checked our two

remaining honeybee hives, one

seemed to be doing fine, but the other had a cluster

as small as the cluster of our now-dead hive when I checked them before

their demise. Every morning thereafter, I put an ear up to the

small hive, and couldn't hear a sound, but warm days this past weekend

did tempt a few bees out to fly around. I have a hard time

imagining that such a tiny hive could bulk back up and survive, but the

frigid temperatures of December and January seem to have broken, so

maybe the cluster will be large enough to make it.

When I last checked our two

remaining honeybee hives, one

seemed to be doing fine, but the other had a cluster

as small as the cluster of our now-dead hive when I checked them before

their demise. Every morning thereafter, I put an ear up to the

small hive, and couldn't hear a sound, but warm days this past weekend

did tempt a few bees out to fly around. I have a hard time

imagining that such a tiny hive could bulk back up and survive, but the

frigid temperatures of December and January seem to have broken, so

maybe the cluster will be large enough to make it.

Why this hive has such

low numbers is a mystery to me. They didn't seem to have gone

through a starvation cycle like our dead hive --- there was honey

within easy reach of the cluster each time I checked. They show

none of the classic signs of varroa mite overinfestation either ---

after watching one valiant worker struggle to haul out dead bee after

dead bee, I swept out about twenty carcasses and saw no mites or

deformed wings. But the colony's population is so low that

something is clearly wrong.

Reading

Ross Conrad's Natural

Beekeeping has

helped me realize that your second winter with a hive is when trouble

is likely to begin. When you receive a package of bees, they

generally arrive relatively disease-free, and it takes a while for

pests and diseases to make their way to the hive. If I'd known

better, I would have been sure to split my hives last year, which would

have helped break the cycle of problems and set each hive back closer

to their package, disease-free state. The good news is that any

hive or hives that survive this second winter are keepers, and I should

be able to split it or them and go into later years with a better

adapted apiary. Still, it's painful to watch and wait and hope

that this tiny colony won't bite the dust.

better, I would have been sure to split my hives last year, which would

have helped break the cycle of problems and set each hive back closer

to their package, disease-free state. The good news is that any

hive or hives that survive this second winter are keepers, and I should

be able to split it or them and go into later years with a better

adapted apiary. Still, it's painful to watch and wait and hope

that this tiny colony won't bite the dust.

Ross

Conrad's theory of natural beekeeping can be summed up as focusing on a

strong, healthy colony rather than on maximum honey output. That

means leaving 60 to 80 pounds of honey on the hive to get them through

his Vermont winters and feeding only in emergencies. If he does

have to feed, he tries to feed honey, then falls back on white sugar.

Ross

Conrad's theory of natural beekeeping can be summed up as focusing on a

strong, healthy colony rather than on maximum honey output. That

means leaving 60 to 80 pounds of honey on the hive to get them through

his Vermont winters and feeding only in emergencies. If he does

have to feed, he tries to feed honey, then falls back on white sugar.

Conrad also believes

that natural beekeepers should aim for genetic diversity and try to

build up hives adapted to our local area. We should let our bees

requeen rather than killing our queen every year or two and ordering a

new one. If you do have to buy a queen, he recommends finding her

locally rather than shipping in bees from across the country which are

adapted to very different climates.

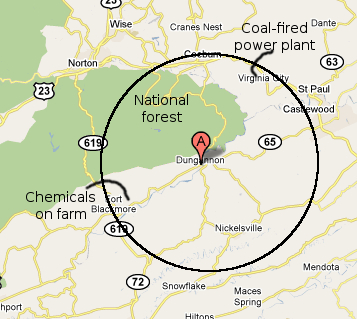

Finally,

he points out that you need to consider an area up to 17 miles in

diameter when keeping your bees happy and healthy. In regular

conditions, studies have shown that about 10% of worker bees fly up to

5.5 miles in search of distant nectar and pollen sources, and that they

may fly as much as 8.5 miles when feed is scarce. So the organic

paradise we offer our bees may be offset by the coal-fired power plant

eight miles away and by the pesticides and herbicides used on the large

strawberry and tomato farm a similar distance in the other

direction. As beekeepers, our work is cut out for us keeping our

far-ranging livestock healthy.

Finally,

he points out that you need to consider an area up to 17 miles in

diameter when keeping your bees happy and healthy. In regular

conditions, studies have shown that about 10% of worker bees fly up to

5.5 miles in search of distant nectar and pollen sources, and that they

may fly as much as 8.5 miles when feed is scarce. So the organic

paradise we offer our bees may be offset by the coal-fired power plant

eight miles away and by the pesticides and herbicides used on the large

strawberry and tomato farm a similar distance in the other

direction. As beekeepers, our work is cut out for us keeping our

far-ranging livestock healthy.

| This post is part of our Natural Beekeeping lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The repair

job I did on the Chopper 1

axe gave out on me today.

It only took a few minutes to

rework the spring and attach it to the splitting finger, but the short

interval between repairs tells me that I should try to find a smaller

replacement spring closer to the size of the original one which is

still doing its job on the other finger with no signs of slowing down.

By Tuesday, the

honeybees had just about mined all the easy fungal spores out of the

sawdust pile.

Or so I assume since only a handful of bees were visiting the patch at

any given time.

By Tuesday, the

honeybees had just about mined all the easy fungal spores out of the

sawdust pile.

Or so I assume since only a handful of bees were visiting the patch at

any given time.

Until, that is, Mark cut

our firewood to length and was suddenly bombarded with honeybees.

One or more of those logs must have been far more full of fungi than

the previous logs were because the bees gathered so many spores I could

see objects in the bees' pollen baskets. (The spores are the

brown clump halfway down the hind leg of the bee in this photo.)

I still have no proof

that these are actually fungal spores being gathered so avidly by our

honeybees, but it sure doesn't look like sawdust in that pollen basket.

Did

you know that around 38% of U.S. bee hives die each year, a number that has more than tripled in the last decade? Most of those deaths aren't from colony

collapse disorder, though, and many can be prevented.

Did

you know that around 38% of U.S. bee hives die each year, a number that has more than tripled in the last decade? Most of those deaths aren't from colony

collapse disorder, though, and many can be prevented.

One of the most valuable

parts of Natural Beekeeping is

information on conducting a hive autopsy. I've excerpted the four

most interesting/likely causes of bee death below, but you'll want to

check the book if you've got conditions that don't fit those listed

here.

- Colony Collapse Disorder is implicated if there are few or no adult bees on the combs or bottom boards --- the bees have just disappeared. There should be capped brood and honey present, and the latter will usually be untouched be robber bees.

- Varroa mites have killed your hive if you see lots of bees with deformed wings and short abdomens and lots of varroa mites on the dead bees, brood, and bottom board. Also look for tiny holes in brood cappings.

- Starvation signs include bees with their heads tucked into comb in search of absent honey and a lack of honey within two inches of the remains of the cluster.

- Pesticide or chemical poisoning results in dead bees in front of the hive with their tongues sticking out.

Knowing the cause of

death will help you decide whether you can reuse

the equipment (yes, unless your bees died of one of the contagious

diseases not mentioned here) and how you can prevent the same fate

befalling your other hives. So dry your tears and poke through

the rubble to become a better beekeeper.

| This post is part of our Natural Beekeeping lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

One of the many advantages to

living in a mobile home is easy access to the roof.

Total time for this chimeny

sweep operation was under 5 minutes.

We

like to prune our everbearing

raspberries so that they produce both a summer and a fall crop,

which is a bit trickier than the conventional method of mowing the

plants all the way down in the winter and getting one big fall

crop. If you're looking for a double harvest, you still prune in

the winter, but have to be a bit more specific about what you cut off.

We

like to prune our everbearing

raspberries so that they produce both a summer and a fall crop,

which is a bit trickier than the conventional method of mowing the

plants all the way down in the winter and getting one big fall

crop. If you're looking for a double harvest, you still prune in

the winter, but have to be a bit more specific about what you cut off.

The first step is to

remove all of the dead canes. These are the canes that fruited

last spring, and they're pretty easy to pick out since they've turned

brown and their bark is peeling, like the cane in the  first

photo.

first

photo.

Next, you want to cut

the tops off the canes that fruited in the fall. Most people

admonish you to cut off the top third, but the truth is that you're

cutting off the dead part. After snipping off a few tops, you'll

start getting an eye for guessing the point at which the plump, live

cane turns into the more shriveled, dead cane. To check your

work, look down at the cut end --- you should see a thin ring of green,

showing that you've cut all the way down to the living tissue.

If you wanted, you could stop

pruning here, but thinning out some of the living canes will give you

bigger, healthier berries in the spring. The rule of thumb is to

leave four or five of the thickest canes per linear foot of row.

The photo above is a before and after shot of this last step in pruning

our raspberry patch.

If you wanted, you could stop

pruning here, but thinning out some of the living canes will give you

bigger, healthier berries in the spring. The rule of thumb is to

leave four or five of the thickest canes per linear foot of row.

The photo above is a before and after shot of this last step in pruning

our raspberry patch.

Now throw down some

compost and a thick layer of mulch and wait for the sweet, juicy

berries in June!

Ross Conrad spends 50 pages

talking about

the varroa mite, which he considers to be the current bane of the

organic beekeeper. Although I'm not interested in trying out his

"soft chemical" controls (which are on a toxicity level similar to Bt),

I'm intrigued by some of the other solutions he presents. Conrad

recommends using many or all of the options below in concert, and

warns that ignoring mites will kill your hive within one to two years

without some mite-reduction actions.

Ross Conrad spends 50 pages

talking about

the varroa mite, which he considers to be the current bane of the

organic beekeeper. Although I'm not interested in trying out his

"soft chemical" controls (which are on a toxicity level similar to Bt),

I'm intrigued by some of the other solutions he presents. Conrad

recommends using many or all of the options below in concert, and

warns that ignoring mites will kill your hive within one to two years

without some mite-reduction actions.

1.

Breed for resistant bees.

Natural beekeepers seem to be unanimous in their admonition to stop

buying out of town bees and to instead learn to breed bees that are

well-suited to

your local conditions. Bees resistant to varroa mites may be more

hygenic, brushing or biting mites off other bees' backs, and they may

also be more prone to swarm. Short of scientifically measuring

these traits, if you reproduce the genetics of the hives that

survive the winter in your apiary, you're automatically selecting for

bees that will do better in your area. (More on how to breed bees

in a later post.) Of course, this is a long term measure and

won't help your bees survive this year.

2. Monitor

for mites to know when to

take drastic action. Although Conrad

mentions several mite-counting

techniques, he takes

a simpler approach and keeps his eye out for

signs of high mite levels when he checks the hive. Noticing mites

on drone brood pulled apart during your hive

check, or wandering around in the hive, is a sign that mite populations

may be increasing and you need to keep an eye on the hive. If you

begin to see deformed wings on worker bees --- caused by a virus

carried by varroa mites --- then mite levels are too high and you must

take emergency measures.

2. Monitor

for mites to know when to

take drastic action. Although Conrad

mentions several mite-counting

techniques, he takes

a simpler approach and keeps his eye out for

signs of high mite levels when he checks the hive. Noticing mites

on drone brood pulled apart during your hive

check, or wandering around in the hive, is a sign that mite populations

may be increasing and you need to keep an eye on the hive. If you

begin to see deformed wings on worker bees --- caused by a virus

carried by varroa mites --- then mite levels are too high and you must

take emergency measures.

3.

Split off nucleus colonies.

The simple action of propagating your hive seems to put a damper on

mite reproduction since splitting causes a pause in brood production

within the

hive. Varroa mites reproduce by laying eggs on bee brood, so if

the bees aren't producing brood, the mites can die out.

4. Use screened bottom boards.

By using a screened bottom board instead of a solid bottom board, when

mites fall off a bee's back, they tend to fall through the holes onto

the ground and die rather than jumping aboard the next bee who passes

by. Screened bottom boards reduce your mite levels by 10 to 20%,

and Conrad notes that even in his northern location, leaving screened

bottom boards open all winter doesn't cause increased winterkill.

4. Use screened bottom boards.

By using a screened bottom board instead of a solid bottom board, when

mites fall off a bee's back, they tend to fall through the holes onto

the ground and die rather than jumping aboard the next bee who passes

by. Screened bottom boards reduce your mite levels by 10 to 20%,

and Conrad notes that even in his northern location, leaving screened

bottom boards open all winter doesn't cause increased winterkill.

5.

Encourage mites to fall.

Various techniques can be used in conjunction with screened bottom

boards to cause even more mite casualties by tricking mites into

loosening their hold on a bee. Plugging up all the holes in a

hive and then filling the hive with the smoke of tobacco, black walnut,

cedar, grapefruit leaves, or creosote bush for 30 to 60 seconds before

airing the hive out causes major mite falls (although tobacco and

creosote smoke may also harm the bees.) Alternatively, you can

sprinkle confectioner's sugar over your bees, which tempts the bees to

groom mites off (but don't use confectioner's sugar during cold weather

since it contains an inert ingredient that your bees will need to void

from their systems.) Both of these techniques should be used when

no honey is present in the hive to prevent contamination, and most

should be repeated two or three times over the course of a few weeks to

catch mites on bees who were out foraging or were in capped brood cells

during the first treatment.

6. Trap mites. Since

varroa mites like drone brood much better than worker brood, you can

kill a lot of mites by putting a sheet of drone foundation in your

hive, waiting for it to be drawn out and filled with capped brood, then

freezing the frame for 26 to 30 hours to kill drones and mites.

You should repeat this technique throughout the year, moving the drone

frame throughout the hive, but it does seem a little hard on all of

those dead drones (who you need if you're going to breed your own new

queens.) Alternatively, Conrad builds mite traps that look like a

deep frame, but with boards on each side covered in slits too small for

a bee to fit through. In the bottom of this little box, he puts a

piece of sticky paper covered with methyl palmitate bait to attract and

then catch the

mites. The sticky paper needs to be changed once in the middle of

summer and the whole trap is removed in August.

6. Trap mites. Since

varroa mites like drone brood much better than worker brood, you can

kill a lot of mites by putting a sheet of drone foundation in your

hive, waiting for it to be drawn out and filled with capped brood, then

freezing the frame for 26 to 30 hours to kill drones and mites.

You should repeat this technique throughout the year, moving the drone

frame throughout the hive, but it does seem a little hard on all of

those dead drones (who you need if you're going to breed your own new

queens.) Alternatively, Conrad builds mite traps that look like a

deep frame, but with boards on each side covered in slits too small for

a bee to fit through. In the bottom of this little box, he puts a

piece of sticky paper covered with methyl palmitate bait to attract and

then catch the

mites. The sticky paper needs to be changed once in the middle of

summer and the whole trap is removed in August.

7.

Use heat to kill the mites.

A temperature of 116.6 degrees Fahrenheit will kill varroa mites, but

not bees, so some beekeepers build special heating chambers into which

they pour their bees once a year to delete the mites. This sounds

pretty tricky, but Conrad also mentions that painting your hive boxes

a dark color might do the job for you --- at temperatures above 97,

brood within the hive will die, but it might be worth it to let the

hive get too hot a few times a year to keep mite levels manageable.

8. Use essential oils of thyme and

mint. A

variety of chemical companies have started making

"organic" mite controls out of thymol and L-menthol dissolved in a

grease patty, but Conrad admits that these chemicals cause a temporary

lull in egg-laying by the queen, which doesn't sound very healthy for

the hive. I wonder if you could plant a bed of thyme and mint

around your hive and get mites to drop off workers as they pass over

the anti-mite planting?

8. Use essential oils of thyme and

mint. A

variety of chemical companies have started making

"organic" mite controls out of thymol and L-menthol dissolved in a

grease patty, but Conrad admits that these chemicals cause a temporary

lull in egg-laying by the queen, which doesn't sound very healthy for

the hive. I wonder if you could plant a bed of thyme and mint

around your hive and get mites to drop off workers as they pass over

the anti-mite planting?

9.

Make your foundation cells smaller.

I've discussed the benefits of foundationless frames

previously. Suffice it to say that if you get your bees to build

cells a more natural size, mites don't fit in as well and mite

populations plummet.

We're already using

options 2 and 4 (and 7 accidentally when we had our

hive meltdown

last summer), and this year I plan to split our hives to

start working on options 1 and 3. I'm curious to see whether

throwing a few black walnut leaves in the smoker when I check on the

hive in the summer might act as a milder version of option 5, and I

hope to remember to plant mint around the hives this year. What

organic techniques do you use to keep your hives' varroa mite levels

within bounds?

| This post is part of our Natural Beekeeping lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Today

was the first day of 2011 where I had to dig out the digital alarm

clock, and I'm happy to report it only got used once in 2010.

Today

was the first day of 2011 where I had to dig out the digital alarm

clock, and I'm happy to report it only got used once in 2010.

Recently I got introduced to

a friend of a friend who has a friend with a very large pile of horse

manure that was looking for a home.

He said we could have it

all...and we're inclined to take him up on the offer while the getting

is so darn good.

I have a confession to

make. When it was 55 degrees on Tuesday and Mark had gone to town

to do our weekly chicken waterer mailing, I snuck out and

weeded a row of berries. It wasn't on the list --- I was supposed

to be pruning --- but the ground had

thawed, and three years of organic mulches had turned the soil into

black, moist humus. The weeds almost seemed to jump out of the

ground into my hands, and my fingers ended up just as black as the soil.

I have a confession to

make. When it was 55 degrees on Tuesday and Mark had gone to town

to do our weekly chicken waterer mailing, I snuck out and

weeded a row of berries. It wasn't on the list --- I was supposed

to be pruning --- but the ground had

thawed, and three years of organic mulches had turned the soil into

black, moist humus. The weeds almost seemed to jump out of the

ground into my hands, and my fingers ended up just as black as the soil.

The chickens were

overjoyed, and so was I. Only later, did I find out that my bout

of winter weeding was akin to self-medication. A few years ago,

scientists discovered that a bacterium in the soil --- Mycobacterium

vaccae --- works

like an antidepressant by tricking our brains into making more

serotonin. Maybe this would explain why the garden-obsessed among

us go a little crazy at this time of year.

Feeling blue? Go

play in the dirt!

Now

that you've slogged through two days of bee doom and gloom, it's time

for a new hope --- splitting your hive in two! I've been daunted

by the notion of hive splitting in the past, since the techniques for

optimal efficiency are

complicated and often require special equipment. But there are

also quick and dirty techniques that work quite well using standard

hive boxes if you only want to create one new hive from each of your

hives rather than turning one hive into as many colonies as possible.

Now

that you've slogged through two days of bee doom and gloom, it's time

for a new hope --- splitting your hive in two! I've been daunted

by the notion of hive splitting in the past, since the techniques for

optimal efficiency are

complicated and often require special equipment. But there are

also quick and dirty techniques that work quite well using standard

hive boxes if you only want to create one new hive from each of your

hives rather than turning one hive into as many colonies as possible.

The simplest way to

split a hive is to begin with double deeps and wait

until both deep boxes are full of brood, honey, and pollen. You

should have a mixture of fresh eggs, uncapped brood, and capped brood

in each box --- if not, swap some around so the two boxes are evenly

filled with brood. Then set up a bottom board in a new

location and carry one of the deep brood boxes over to place on

it. Shake some extra nurse bees into the box, put on the inner

and outer cover, add an entrance reducer, and you're done.

One of the split hives will

have the queen in it --- this is the mother

colony --- while the other will realize they are queenless and will

quickly turn one of the eggs into a queen. Within a few days, you

should be able to tell the difference in the hives. Treat the

mother

colony the way you would any other hive, but leave the nucleus (aka

"nuc" --- the hive with no queen) alone for 30 days to let them raise a

queen and give her time to start laying.

One of the split hives will

have the queen in it --- this is the mother

colony --- while the other will realize they are queenless and will

quickly turn one of the eggs into a queen. Within a few days, you

should be able to tell the difference in the hives. Treat the

mother

colony the way you would any other hive, but leave the nucleus (aka

"nuc" --- the hive with no queen) alone for 30 days to let them raise a

queen and give her time to start laying.

Inevitably, most of the

foraging bees will drift back to the hive in

the old location, which is why you put some extra bees in the hive you

carted to a new spot. This is also why you want to make sure both

hives have at least a few frames of pollen and honey to get them

started while they regroup and get back on track.

As long as you carry out

your split early in the year --- I figure April or May in our area ---

you shouldn't have to give either hive supplemental feed. You

won't get as much honey that year as you would have without performing

the split, but you will probably be able to harvest at least a bit of

honey from the mother hive (and maybe from the nuc as well.) I've

decided to try this out with both of our hives, if they seem strong

enough, and hope that we'll end 2011 with four hives instead of two.

| This post is part of our Natural Beekeeping lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The new Kobalt

never-flat wheelbarrow

can handle what seems like twice the volume as our old ramshackled

pneumatic version, which

had a habit of wobbling back and forth when she had a large load.

Now that I've had a chance to

use it with multiple loads I think I could guess that the new

never-flat technology increases rolling

resistance around 10 percent compared to an air filled tire.

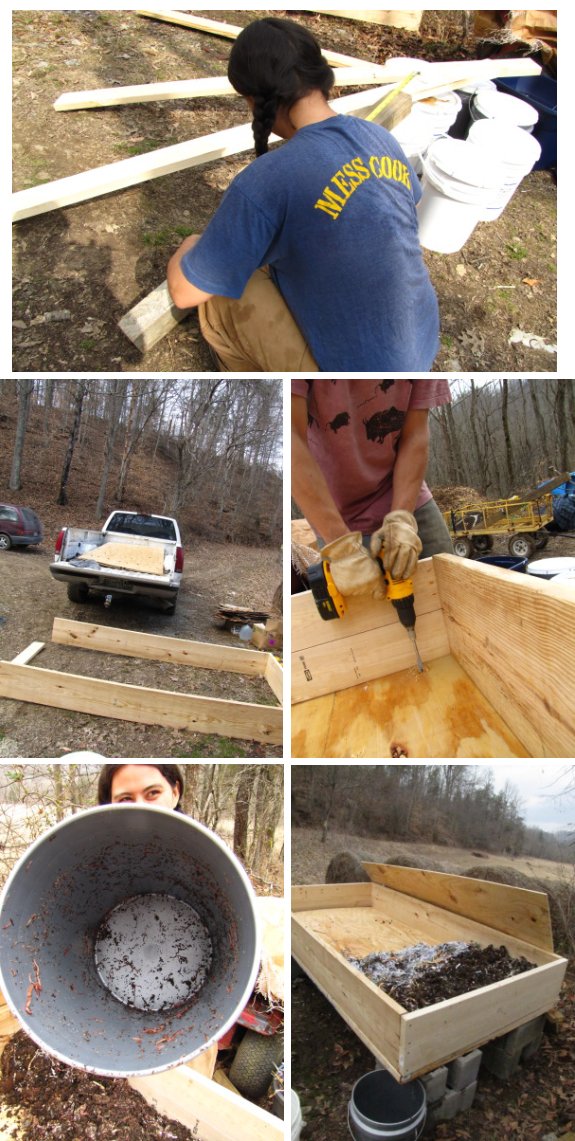

We got our first

delivery of food

scraps from the local school! As Mark suspected,

once the bulky milk cartons were separated out, the scraps were much

smaller than anticipated. Since we're working the kinks out of

our system, small is good...for now.

Although

we're excited to get started, we have to get an idea of how much food

we'll get each week before we build the worm bin. We had

originally planned to give the initial round of food scraps to the

chickens after weighing them, but learned just in time that health

department policy says no food scraps from public facilities can be

given to livestock.

Although

we're excited to get started, we have to get an idea of how much food

we'll get each week before we build the worm bin. We had

originally planned to give the initial round of food scraps to the

chickens after weighing them, but learned just in time that health

department policy says no food scraps from public facilities can be

given to livestock.

That put us in a bit of

a bind, since the only outside area that Lucy knows is off-limits is

the chicken pasture (which is where we usually build our compost

piles.) Luckily, Mark's friend had found a stock tank with a hole

in it at the dump a few months ago and my mom had given us a few pieces

of scrap plywood. Add on some cinderblocks and we had a dog-proof

container with a handy drainage hole at the bottom.

We laid down a layer of

wood chips, dumped the food scraps on top, and topped them off with

another layer of wood chips. So far, we don't have enough data to

make a real estimate, but if we continue to get the same amount of

food, we'll only need a small worm bin --- roughly three feet by four

feet by one foot. I wonder if this will be big enough to get all

of the benefits

of mid-scale worm bins?

Would we be better off building a slightly larger bin? Plenty to

ponder before we make decisions.

It

occurred to me while pulling this fence post up that there should be

some sort of device you could hook up to the bottom and pump with your

foot which would utilize some jacking leverage to power it out.

It

occurred to me while pulling this fence post up that there should be

some sort of device you could hook up to the bottom and pump with your

foot which would utilize some jacking leverage to power it out.

The name Post-Up comes to mind...but the

more I thought about it the more I started thinking that it's most

likely easier to just wiggle it back and forth and pull, pull, and pull

till it's free.

Mark

and I put together a quick

hoop on Monday

and I was about to tell you about it...when it blew away. So

we adapted the design to give the structure a lower profile, which

incidentally resulted in some extra fabric on the edges to roll around

lengths of rebar. The rebar is just flexible enough to follow the

contour of the soil when weighted down with bricks, but is still

straight enough to keep the edge of the row cover from blowing up and

letting the wind rip under the quick hoop.

Mark

and I put together a quick

hoop on Monday

and I was about to tell you about it...when it blew away. So

we adapted the design to give the structure a lower profile, which

incidentally resulted in some extra fabric on the edges to roll around

lengths of rebar. The rebar is just flexible enough to follow the

contour of the soil when weighted down with bricks, but is still

straight enough to keep the edge of the row cover from blowing up and

letting the wind rip under the quick hoop.

Our farm is tucked down

into a hollow between two hills, so a gentle

breeze is usually something to be remarked upon, but this week has been

full of roaring winds. I figure that's a good thing --- most of

you probably have much more wind than we do, and it would be a shame to

tell you how to build a structure that would promptly blow apart in

your garden. Which is all a long way of saying --- I promise you

more information on quick hoop construction once we're sure the

structure will stand the test of time.

Thanks Shannon for

pointing out the above T-post puller which can be found for a bit

under a hundred dollars.

The design is clever, but I

don't think it would work with our lower grade fence posts.

These lighter posts are more

like a U shape. They fit in well with our applications at less than

half the price of the sturdier T-post.

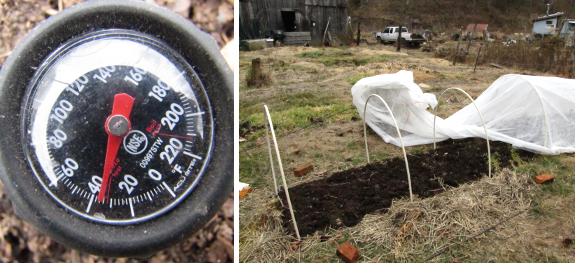

Two days after reinstalling

our quick hoop, the

soil temperature underneath the protective fabric was already four

degrees warmer than soil temperature on a neighboring bed!

Granted, I had raked back the mulch on the neighboring bed just like I

did on my quick hoop bed, but hadn't applied juicy, warm manure, so

it's possible the manure application is part of the reason for my fast

soil heating.

Truthfully, though, I

don't care if it's the quick hoop or the manure that kicked my soil

temperature up to 36. I'm just thrilled that it's finally warm

enough to plant my first lettuce bed. Fresh lettuce in four

weeks if all goes well!

I

know that it hasn't been that long since you choked your way through a

lunchtime series on urine, but Liquid Gold got me so fired up that I

started a slew of experiments. I apologize in advance to those of

you with weak stomachs, but I'm going to subject you to another week of

urine ramblings.

I

know that it hasn't been that long since you choked your way through a

lunchtime series on urine, but Liquid Gold got me so fired up that I

started a slew of experiments. I apologize in advance to those of

you with weak stomachs, but I'm going to subject you to another week of

urine ramblings.

First up --- how to

collect that pee. Since we don't have an indoor bathroom, Mark

had been peeing into a milk jug for months before I got obsessed with

using urine as fertilizer --- it was just simpler (and warmer) than

going outside. So I didn't have a hard time talking him into

giving up his liquid gold for my experiments, though I did ask if he

might like a fancy,

homemade urinal.

Mark rolled his eyes and told me the gallon jug worked just

fine.

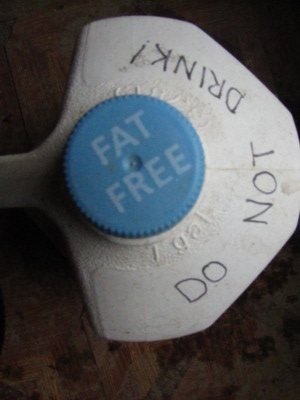

Mark did make one slight

modification to his milk jug --- he printed "DO NOT DRINK!" in large

letters around the rim of the container. During cold spells, we

often imbibe water out of cleaned out milk jugs (filled during warm

spells), so the warning label is a good precaution. In households

with more regular running water, you wouldn't even need that.

| This post is part of our Urine in the Garden lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The new Kobalt wheelbarrow has enough

volume to handle 6 cubic feet, but when it comes to heavy gravel on

muddy terrain my new limit is somewhere between 4 and 5 depending on

how much elbow grease I can muster.

The truck, wheelbarrow, and

shovel got a real workout yesterday, with me and Mark using them in

shifts. First, I unloaded the rest of the manure on top of half a truckload

of imperfect

chicken compost so

that Mark could drive out to get gravel while the ground was still

frozen. All morning, I spread manure in the mule garden,

focussing on the beds that we'll be planting in February and

March. Mark got home just as I was finishing up and took the

wheelbarrow out to work

on the driveway.

I estimate we each moved about the same volume of material, which means

he probably worked about three times as hard as I did.

The truck, wheelbarrow, and

shovel got a real workout yesterday, with me and Mark using them in

shifts. First, I unloaded the rest of the manure on top of half a truckload

of imperfect

chicken compost so

that Mark could drive out to get gravel while the ground was still

frozen. All morning, I spread manure in the mule garden,

focussing on the beds that we'll be planting in February and

March. Mark got home just as I was finishing up and took the

wheelbarrow out to work

on the driveway.

I estimate we each moved about the same volume of material, which means

he probably worked about three times as hard as I did.

In the past, I've been

extremely frugal with compost and manure, but now that we have a

better supply (and a truck to haul it with), I'm adding a solid inch to

each garden bed, the amount recommended by soil builders. Being

so profligate with manure, though, means that even Mark's huge compost

pile may not be enough. I figure I need about six more truckloads

(14.4 cubic yards) to treat the whole garden, orchard, and berry patch

right. It feels like a very ambitious plan, but I suspect that

after a year or two of heavy manuring, we'll be able to keep fewer beds

in production and cycle some through low-work cover crops. My new

goal --- the same amount of high quality food with less work.

The

first place I wanted to use urine was to fertilize my nitrogen-hungry

dwarf potted citrus trees. Our movie star neighbor has the

most

amazing dwarf Meyer lemon tree anyone has ever seen, and he attributes

part of his success to regular doses of miracle grow. I'm leery

of chemical fertilizers and wondered if urine would work as well.

The

first place I wanted to use urine was to fertilize my nitrogen-hungry

dwarf potted citrus trees. Our movie star neighbor has the

most

amazing dwarf Meyer lemon tree anyone has ever seen, and he attributes

part of his success to regular doses of miracle grow. I'm leery

of chemical fertilizers and wondered if urine would work as well.

For my first attempt, I

ignored

instructions and poured straight urine

around the roots of my citrus trees, washing the pee in

with plenty of water. I thought the mix-in-the-pot technique

should work, but the plants complained, so my next trial consisted of

mixing urine and water in a bucket at a proportion of roughly one part

urine for six parts water, then using that mixture on the plants.

This time, the plants were pleased.

In fact, our dwarf Meyer

lemon was so pleased it popped out in

literally hundreds of blooms! Now, from my vague understanding of

the bloom-decision-process in fruit trees, I think the number of

flowers must have been decided before I started pouring urine around

her roots (although I'm not positive about that.) The real test

will be how many of those flowers she sets into fruit since my

experience has been that our Meyer lemon drops a large percentage of

the young fruits soon after blooming. I have high hopes that

giving her plenty of nitrogen during that critical fruit-setting period

might help us keep a higher percentage of fruits this year and get a

bumper crop of lemons next winter. As the old saying goes, "If

you've got urine, make lemonaide."

flowers must have been decided before I started pouring urine around

her roots (although I'm not positive about that.) The real test

will be how many of those flowers she sets into fruit since my

experience has been that our Meyer lemon drops a large percentage of

the young fruits soon after blooming. I have high hopes that

giving her plenty of nitrogen during that critical fruit-setting period

might help us keep a higher percentage of fruits this year and get a

bumper crop of lemons next winter. As the old saying goes, "If

you've got urine, make lemonaide."

| This post is part of our Urine in the Garden lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I've found that using a

dedicated pair of gloves for sticky

roofing chores makes the

clean up process quick and easy.

We

kept our homegrown

rooster because I want to try to raise our own chicks this year,

but I have to admit that until recently I still muttered "freeloader"

under my breath whenever I saw him. He started to prove his worth

when we integrated three flocks --- the rooster's

mitigating instinct means that even the lowest chicken on the totem

pole gets to eat at the table and doesn't get picked on too much. But while shoveling

manure, I discovered that the rooster was even more useful than I

thought.

We

kept our homegrown

rooster because I want to try to raise our own chicks this year,

but I have to admit that until recently I still muttered "freeloader"

under my breath whenever I saw him. He started to prove his worth

when we integrated three flocks --- the rooster's

mitigating instinct means that even the lowest chicken on the totem

pole gets to eat at the table and doesn't get picked on too much. But while shoveling

manure, I discovered that the rooster was even more useful than I

thought.

I soon turned up a big fat

grub and headed over to the chicken pasture to give the girls a

treat. The only chicken outside, though, was the rooster, so I

decided it was time for a real test. When I bring out the scraps

in the morning, the rooster is quite a gentleman, picking out the best

pieces and clucking over them until one of his harem takes the treat,

but I figured he'd just eat up the grub when left to his own

devices. I lobbed the beetle larva under his nose, and the

rooster immediately started clucking like crazy. He picked up

that grub, dropped it back down to the ground, and clucked some

more. Within seconds, a hen came to see what the fuss was about,

and the grub went down her gullet faster than I could pull out the

camera.

I soon turned up a big fat

grub and headed over to the chicken pasture to give the girls a

treat. The only chicken outside, though, was the rooster, so I

decided it was time for a real test. When I bring out the scraps

in the morning, the rooster is quite a gentleman, picking out the best

pieces and clucking over them until one of his harem takes the treat,

but I figured he'd just eat up the grub when left to his own

devices. I lobbed the beetle larva under his nose, and the

rooster immediately started clucking like crazy. He picked up

that grub, dropped it back down to the ground, and clucked some

more. Within seconds, a hen came to see what the fuss was about,

and the grub went down her gullet faster than I could pull out the

camera.

As much as I hate to say

I was wrong, I have to admit that our rooster is far from a

freeloader. He's definitely going to remain an integral part of

the flock.

Fertilizing

our house plants with urine seems to be working great, but once

Mark

started bottling his pee, I realized that we had too much of a good

thing. What to do with the extra?

Fertilizing

our house plants with urine seems to be working great, but once

Mark

started bottling his pee, I realized that we had too much of a good

thing. What to do with the extra?

Urine is so high in

nitrogen that one of its best uses is mixing

with high carbon compounds to create a C:N ratio more suited to

decomposition. Although I use large

cardboard boxes for kill

mulches as soon as we get them (sometimes emptying out components

early

to get to those important boxes), small cardboard boxes tend to pile

up, waiting for a use. Time to see if we can compost them with

pee!

Following the lead of

someone mentioned in Liquid Gold,

I filled a plastic bin with cardboard, making sure that the cut ends

all faced up. By laying the cardboard vertically in the box

rather than horizontally, I made it much more likely that urine will

soak down into each layer and get to work rather than puddling in the

top few layers. I didn't want the cardboard to get waterlogged,

so I figured I could either put holes in the bottom of the bin and put

it outside, or leave the bin intact and move it out of the weather, and

I chose the latter. The final step was to pour a gallon of urine

over the cardboard. I'll try to remember to check on the bin at

intervals and pour on more pee if the cardboard seems dry, but

otherwise I'll just leave the decomposition chamber to do its thing and

report on the experiment in six months to a year.

| This post is part of our Urine in the Garden lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The first

chicken pasture coop

worked out fine during the summer months, but our hillside blocks all

the winter sun and makes the chickens a bit grumpier than they should

be.

The first

chicken pasture coop

worked out fine during the summer months, but our hillside blocks all

the winter sun and makes the chickens a bit grumpier than they should

be.

A second coop with more

pasture is now planned for a more sunny location.

I'm pretty sure I can use the

above load of pallets for most of the building materials, just not sure

exactly which way it will all go together yet.

When

Mark's not home, I often do stupid things. The trouble is that

I'm not very patient and I don't like to admit that anything's beyond

my abilities --- in other words, waiting for Mark to get home and help

me with a task is often too tough. That's how I ended up with

bags of food scraps floating down the creek and me jumping into the

freezing water after them.

When

Mark's not home, I often do stupid things. The trouble is that

I'm not very patient and I don't like to admit that anything's beyond

my abilities --- in other words, waiting for Mark to get home and help

me with a task is often too tough. That's how I ended up with

bags of food scraps floating down the creek and me jumping into the

freezing water after them.

It all started when the

ground froze good and solid and Mark headed to the big city to pick up

a truckload of pallets. I'd been aching for a day like this to

haul in the rest of our firewood since the woodshed was nearly empty

and we had a full cord sitting out at the parking area, so I jumped in

the golf cart and started hauling. On the third trip, though,

something was clearly wrong --- an area around the back wheels started

squealing like crazy and the cart began to lose power at

intervals. Yikes! I stabled our intrepid golf cart and

moved onto the next thing on my agenda --- heading into town to mail chicken waterers and pick up the week's food

scraps. Based on the

small amount of scraps we'd gotten last week, I figured I could easily

wheel the scraps home with our fancy

new wheelbarrow.

haul in the rest of our firewood since the woodshed was nearly empty

and we had a full cord sitting out at the parking area, so I jumped in

the golf cart and started hauling. On the third trip, though,

something was clearly wrong --- an area around the back wheels started

squealing like crazy and the cart began to lose power at

intervals. Yikes! I stabled our intrepid golf cart and

moved onto the next thing on my agenda --- heading into town to mail chicken waterers and pick up the week's food

scraps. Based on the

small amount of scraps we'd gotten last week, I figured I could easily

wheel the scraps home with our fancy

new wheelbarrow.

At

the school, I discovered that the kids have started learning the system

better, which means that food scraps end up in our bin instead of in

the trash. As a result, we got nearly twice as much food scrap

volume as last time --- exciting! At this point, if I was smart,

I would have noticed that the driveway was starting to thaw out and

would have chosen to split the scraps into two loads, or might have

vetoed the wheelbarrow expedition entirely and waited until Mark came

back and the driveway froze again to drive the compostables home.

But, being who I am, I instead loaded the wheelbarrow to the brim and

went merrily on my way.

At

the school, I discovered that the kids have started learning the system

better, which means that food scraps end up in our bin instead of in

the trash. As a result, we got nearly twice as much food scrap

volume as last time --- exciting! At this point, if I was smart,

I would have noticed that the driveway was starting to thaw out and

would have chosen to split the scraps into two loads, or might have

vetoed the wheelbarrow expedition entirely and waited until Mark came

back and the driveway froze again to drive the compostables home.

But, being who I am, I instead loaded the wheelbarrow to the brim and

went merrily on my way.

It's downhill for the first

quarter of the journey, and that was easy, but then I came to the

ford. I hadn't thought this expedition through, so I was just

wearing my work boots, which means I had to hop on blocks on the side

of the ford to get across the creek. Did you know that

wheelbarrows don't hop on blocks? The overloaded wheelbarrow and

I did some weird contortions, trying to get across the creek together

without my feet getting wet, and then she tiiiiiiiiipppppped.....

It's downhill for the first

quarter of the journey, and that was easy, but then I came to the

ford. I hadn't thought this expedition through, so I was just

wearing my work boots, which means I had to hop on blocks on the side

of the ford to get across the creek. Did you know that

wheelbarrows don't hop on blocks? The overloaded wheelbarrow and

I did some weird contortions, trying to get across the creek together

without my feet getting wet, and then she tiiiiiiiiipppppped.....

I didn't fall in the

creek --- that's about the only thing I did right. I just let the

wheelbarrow tip over and snagged the one bag still within reach,

wheeling the empty wheelbarrow to the top of the ford. But I had

to get even wetter to capture the other bags as they floated merrily

away down the creek (not polluting the water, luckily --- they were

sealed.) A few minutes later, I had a very cold, wet foot, but

the food scraps were rescued and back in the wheelbarrow.

I

thought I was home free, but the top inch of driveway had turned into

mud that coated the overloaded wheelbarrow's wheel and made it nearly

impossible to push. Just as I gave up, Lucy got engrossed in

digging a rodent out of the woods, which is good since I otherwise

couldn't have left the food scraps unattended around her. I

hurried home, begged the golf cart to give me one more trip, and drove

down to rescue my wheelbarrow and food scraps. We made it home at

last and I weighed and covered up the food scraps in their temporary

compost bin before heading inside to dry my shoe. I know I'll

regret this episode later when the boot is still damp inside, but

for now, I'm just happy that I got the job done, even if I put in five

times as much energy as I needed to.

I

thought I was home free, but the top inch of driveway had turned into

mud that coated the overloaded wheelbarrow's wheel and made it nearly

impossible to push. Just as I gave up, Lucy got engrossed in

digging a rodent out of the woods, which is good since I otherwise

couldn't have left the food scraps unattended around her. I

hurried home, begged the golf cart to give me one more trip, and drove

down to rescue my wheelbarrow and food scraps. We made it home at

last and I weighed and covered up the food scraps in their temporary

compost bin before heading inside to dry my shoe. I know I'll

regret this episode later when the boot is still damp inside, but

for now, I'm just happy that I got the job done, even if I put in five

times as much energy as I needed to.

Mark's motto is "Work

smart, not hard." My motto, apparently, is "Jump in the creek

when it's below freezing outside! It's fun!"

I've

discussed the benefits of

biochar before, but as I did more research, I realized that

gardening with biochar isn't as simple as taking charcoal and throwing

it in your soil. Instead, you need to prepare the charcoal a bit

to get best results. The first step in preparation is soaking the

charcoal --- charcoal is naturally hydrophobic, so you have to overcome

that barrier to water. The second step is to add some kind of

high nitrogen input to the charcoal to give the first microorganisms

something to eat. You can do both preparation steps at once using

urine.

I've

discussed the benefits of

biochar before, but as I did more research, I realized that

gardening with biochar isn't as simple as taking charcoal and throwing

it in your soil. Instead, you need to prepare the charcoal a bit

to get best results. The first step in preparation is soaking the

charcoal --- charcoal is naturally hydrophobic, so you have to overcome

that barrier to water. The second step is to add some kind of

high nitrogen input to the charcoal to give the first microorganisms

something to eat. You can do both preparation steps at once using

urine.

I

filled a four gallon bucket with biochar and poured a gallon

of urine over top. The charcoal chunks snapped, crackled, and

popped just like rice cereal as they soaked up the liquid, and only a

scant half cup was left in the bottom of the bucket a few hours

later. I'll apply the mixture to the garden soon and hope that

microorganisms get to work on the fertilized biochar in time to see

results in this year's garden. (Much more on biochar to come in

next week's lunchtime series.)

| This post is part of our Urine in the Garden lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I recently discovered that white lithium grease is a much more

appropriate lubricant to use than WD-40 when it comes to items that are

open to the elements.

It provides a thick coat that stays in place and won't freeze.

The technical name for it is Cerflon, which uses a carbon-flourine

bond to form a ceramic reinforced fluoropolymer.

In

the past, I've direct-seeded onions at the beginning of March.

The first year, we had a

great harvest.

The second year, I put

the onions in the worst part of the garden and the clayey, waterlogged

soil resulted in puny onions. And last year was even worse --- I

didn't even get any of the onion seeds to sprout! Clearly, I need

to do something different this year.

In

the past, I've direct-seeded onions at the beginning of March.

The first year, we had a

great harvest.

The second year, I put

the onions in the worst part of the garden and the clayey, waterlogged

soil resulted in puny onions. And last year was even worse --- I

didn't even get any of the onion seeds to sprout! Clearly, I need

to do something different this year.

Year two's mistake is

easy to remedy --- I'll be planting my onions in

the deeper soil of the mule garden from now on. And I suspect

that part of my problem last year was shoddy seeds, so we've changed

our loyalties to a seed company with a better reputation

(Johnny's). Still, I want to try giving our precious Alliums a bit of extra protection in

the 2011 garden.

The

first method I'm using is more work (from me) and more energy (from

the electric grid), but I want to hedge my bets and make sure I get at

least some onions this year. So I've started a flat of onions

inside and might start one or two more. The problem with starting

seeds indoors is that I'm committing to running grow lights for a

couple of months, and I also have to give the seedlings extra TLC at

the transplanting stage, but it does make me happy to play in the soil

in early February.

The

first method I'm using is more work (from me) and more energy (from

the electric grid), but I want to hedge my bets and make sure I get at

least some onions this year. So I've started a flat of onions

inside and might start one or two more. The problem with starting

seeds indoors is that I'm committing to running grow lights for a

couple of months, and I also have to give the seedlings extra TLC at

the transplanting stage, but it does make me happy to play in the soil

in early February.

Meanwhile, I'll be

starting some onion seeds directly in the ground

under quick hoops

within the next few weeks. Onion seeds are

supposed to need the same soil temperature for germination as lettuce,

so I could probably plant them under quick hoops right now,

but I want to tweak our design a bit before I build another quick hoop

structure.

Of

course, we're growing several beds of potato

onions too, but I'm

still not sold on the idea that these perennial onions will make big

bulbs. We'll just have to wait and see which method gives us the

best onions in 2011.

Of

course, we're growing several beds of potato

onions too, but I'm

still not sold on the idea that these perennial onions will make big

bulbs. We'll just have to wait and see which method gives us the

best onions in 2011.

Once

I started collecting my own urine (with the quick and dirty contraption

shown here), I suddenly had a lot more to play with. In fact, I

ran out of projects dying for an immediate dose of nitrogen and ended

up wandering around the garden with a jug of liquid gold in my hand.

Once

I started collecting my own urine (with the quick and dirty contraption

shown here), I suddenly had a lot more to play with. In fact, I

ran out of projects dying for an immediate dose of nitrogen and ended

up wandering around the garden with a jug of liquid gold in my hand.

Aha! The fall

compost pile was sitting there doing nothing, mostly because I'd made

it completely out of late summer weeds, which have a higher C:N ratio

than spring weeds and decompose very slowly on their own. Time to

see if a regular dose of urine will speed up the composting process.

That's all of our urine

experiments for now, but I'm sure I'll come up with more as the pee

starts piling up again. Have you gotten inspired and started to

use your urine in your garden? What's your favorite method?

| This post is part of our Urine in the Garden lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our new stove seemed to have

a problem with leaking smoke and heat out of the top right burner in

the back. After a few minutes of research we found out this is normal

and all stoves have this vent hole to prevent explosions, but our old

one never seemed to leak any smoke.

It only took about 10 minutes

to take the old grid thing out and make room for it in the new vent

hole, which seems to have stopped the leaking smoke problem.

When small talk runs

toward the weather, just about everyone tells me that they're heartily

sick of winter. The truth is that it's been an abnormally cold

and snowy winter for our region, but I can't get behind that

sentiment. Yes, my green thumb is aching for spring, but at the

same time, there is so much joy to be found in a snow-covered quick hoop in February, in crocus

leaves sticking up through the frozen soil, and in forsythia forced to

bloom early on a windowsill. (Thanks for the cutting, Mom!)

There's the sheer

rapture of baking my chilly toes in front of a wood stove on a frigid

day. The way my long johns hug me after I dash out of my cold

bedroom to find them. And the way the late sunrise gives me

permission to sleep in.

Although we don't talk

about it much here, Mark's patented system of positive thought is 25%

of the Walden Effect. So cheer yourself up and find the sunny

side of February. What's your favorite part of this last full

month of winter?

We've lost about a dozen butternut

squashes this year due to

freezing.

The problem was a decision on

how high to set the space heater when we went on vacation.

I remember Anna saying

"Should we put it on level 2?"....."Nahhhh...level 1 should be fine",

was my reply.

I read a lot of blogs, but only a handful

captivate me enough that I talk about them with Mark around the dinner

table. Sharon Astyk's blog is so thought-provoking that we

discuss "blogger Sharon" at least once a week. Since Sharon is

also an author, it seemed like a no-brainer to check one of her books

out of the library.

I read a lot of blogs, but only a handful

captivate me enough that I talk about them with Mark around the dinner

table. Sharon Astyk's blog is so thought-provoking that we

discuss "blogger Sharon" at least once a week. Since Sharon is

also an author, it seemed like a no-brainer to check one of her books

out of the library.

Depletion

and Abundance

fleshed out the thesis I've been picking up in bits and pieces on

Sharon's blog --- peak oil and climate change are going to change the

face of our world, and we need to be prepared for a lower energy future

full of good food and friends (and hard work.) Then there's the

Anyway clause --- even if you don't believe in peak oil and climate

change, the actions you would take to prepare for those eventualities

are just the right thing to do anyway.

Unfortunately, since I'd

been reading her blog for months, I was a bit disappointed to be

getting the same information again in book form. I kept hoping

we'd make our way out of the big picture and that Sharon would write

more about the minutae --- for example, I was aching to hear about how

her family cut their energy usage to 10% of the national average over

the course of a year. (Perhaps that tale is in one of her

other books?)

People who enjoy

philosophizing will probably take to Depletion

and Abundance

better than I did. I tend to look for solid answers when I read a

book (or at least for a record of what worked and didn't work in the

author's own experience.) Instead, Sharon's book is full of

thought-provoking questions about home and community, but not enough

hard data to really suck me in. Still, I'd recommend that you

pick up Sharon Astyk's book, or at least add her blogs to your reading

list for exactly the minutae I missed in her book --- milk goats,

homeschooling, canning, and much more. Sharon writes one blog

about "food, farm, and family" and another on Science Blogs

about the more technical side of peak oil and climate change.

When we first started the hoop

house project there was an experiment to use pieces of hose

material cut lengthwise to secure the Agribon fabric to the PVC frame.

It didn't work.

The hose pieces fit nicely

around the PVC pipe, but the pressure was just too much for it to keep

the fabric attached. We ended up making the hoop shorter so that

we could have some extra fabric on the bottom to roll up and weigh down

with 10 foot long sections of rebar and bricks.

What

do you do for food on the road? We used to pack sandwiches a lot,

but have been reducing our grain intake drastically lately, which

leaves me in a bit of a bind. Instead, we've ended up visiting

restaurants with lots of vegetables on the menu, but we've become such

snobs that anyone's vegetables except our own leave us feeling a bit

empty (and I hate to pay for restaurant food very often.)

What

do you do for food on the road? We used to pack sandwiches a lot,

but have been reducing our grain intake drastically lately, which

leaves me in a bit of a bind. Instead, we've ended up visiting

restaurants with lots of vegetables on the menu, but we've become such

snobs that anyone's vegetables except our own leave us feeling a bit

empty (and I hate to pay for restaurant food very often.)

On the way back from

visiting Mark's folks in Ohio this past weekend, Mark's step-mom hooked

us up with this fancy container that makes picnicking with real food

much easier. You fill the container up with hot water and let the

warmth soak in for a few minutes, then dry the container out and put in

your hot food. Three hours later when we finished exploring an

Indian mound, the vittles were still toasty and ready for our picnic.

What are your favorite

traveling recipes and methods?

I've been intrigued by terra

preta

ever since I first heard about it, and am equally intrigued by its

modern grandchild, biochar. Last year, Mark and I attended a

workshop on biochar and came away with a lot of information about how biochar is

used in large scale agriculture.

I resolved to put biochar to use in our 2011 garden, then got bogged

down in the details of how to tweak the technology to fit the backyard

scale. Did I need to build a special piece of equipment to make

the biochar? Did I need to grind the biochar? To charge or

activate it? Is biochar compatible with no-till or does it have

to be worked into the soil? And what exactly happens when you put

biochar in the soil?

I've been intrigued by terra

preta

ever since I first heard about it, and am equally intrigued by its

modern grandchild, biochar. Last year, Mark and I attended a

workshop on biochar and came away with a lot of information about how biochar is

used in large scale agriculture.

I resolved to put biochar to use in our 2011 garden, then got bogged

down in the details of how to tweak the technology to fit the backyard

scale. Did I need to build a special piece of equipment to make

the biochar? Did I need to grind the biochar? To charge or

activate it? Is biochar compatible with no-till or does it have

to be worked into the soil? And what exactly happens when you put

biochar in the soil?

In this week's lunchtime

series, I do my best to answer those questions. I delved into

several books and websites in the research process, but the ones I

think you'd enjoy the most are:

Lehmann, Johannes, and Stephen

Joseph. 2009. Biochar

for Environmental Management. Earthscan Publications,

Ltd., London.

Lehmann, Johannes, and Stephen

Joseph. 2009. Biochar

for Environmental Management. Earthscan Publications,

Ltd., London.

| This post is part of our Biochar in the Backyard lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I left this large pot out all

winter and somehow the lid blew off and filled up with water.

Big mistake!

I'm not sure why I didn't put

it away in the barn back in the fall...it was fine like that the last 3

winters, but I guess these cold spells of 2011 were just too much for

its made in China construciton.

I'll do a bit of research

before we find a replacement. The size was perfect for dunking chickens

in on processing day, but maybe aluminum wasn't the best metal for this

application.

I've

always been confused by frost

free dates,

especially after asking two local extension agents for information and

getting two very different answers. So I was thrilled to stumble

upon a tool that gives me actual data

from local weather stations while also clearing up the mystery.

I've

always been confused by frost

free dates,

especially after asking two local extension agents for information and

getting two very different answers. So I was thrilled to stumble

upon a tool that gives me actual data

from local weather stations while also clearing up the mystery.

Frost free dates are

like flood zones. If you live in a wet region like ours, you'll

want to head to the local authorities to find a map showing 10 year and

100 year flood zones. The idea is that, on average, waters will

reach the 10 year flood line once every decade and the 100 year flood

line once per century. Of course, this is a statistical tool, not

a forecast, so you might get a 100 year flood three years running, or

might not get one for 300 years. But either way, you won't want

to build your house in the 10 year flood zone, and probably shouldn't

put it in the 100 year flood zone either.

Similarly, frost free dates

are reported based on the percentage likelihood of seeing frost on a

certain day in the spring. Using data from our closest weather

station, we have a 10% chance of seeing frost as late as May 16,

compared to a 90% chance of seeing frost on April 12. On average,

our last frost falls on April 29. So, in a way, those extension

agents were both right. One was being careful and giving me the

date after which frost will nearly never occur while the other was more

of a gambler and figured we could plant on the average last frost date.

Similarly, frost free dates

are reported based on the percentage likelihood of seeing frost on a

certain day in the spring. Using data from our closest weather

station, we have a 10% chance of seeing frost as late as May 16,

compared to a 90% chance of seeing frost on April 12. On average,

our last frost falls on April 29. So, in a way, those extension

agents were both right. One was being careful and giving me the

date after which frost will nearly never occur while the other was more

of a gambler and figured we could plant on the average last frost date.

The Dave's Garden tool also

tells me the chances of seeing 28

degree frosts (which will nip our peach blossoms) and 24 degree

frosts (which will kill unprotected broccoli.) If I hadn't decided

to change over to using

soil temperature as my method of choosing planting dates, I can tell this tool would

be worth its weight in gold.

The Dave's Garden tool also

tells me the chances of seeing 28

degree frosts (which will nip our peach blossoms) and 24 degree

frosts (which will kill unprotected broccoli.) If I hadn't decided

to change over to using

soil temperature as my method of choosing planting dates, I can tell this tool would

be worth its weight in gold.

(In case you're curious,

the photos in this post are from our trip to Ohio, where there's still

lots of snow on the ground. You can see my review

of Mound City over

on our travel blog.)

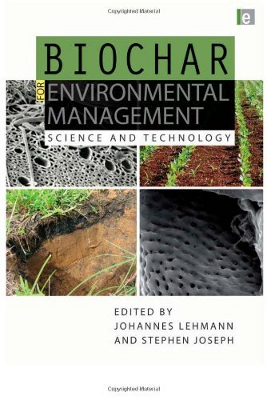

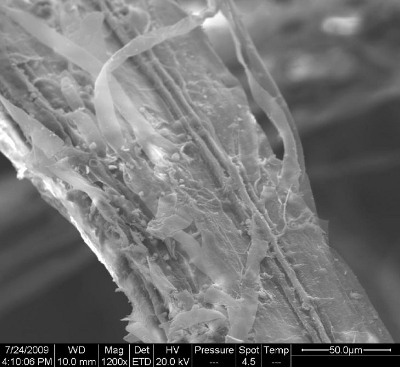

I've posted previously about

the benefits

of biochar, but how

does biochar actually cause those increases in crop yield? It's

probably easiest for the average gardener to understand that the

increase in pH is caused by the ash that inevitably comes along for the

ride --- using wood

ashes to increase the alkalinity of (or "sweeten") soil is common

wisdom among farmers. And we can visualize the water retention

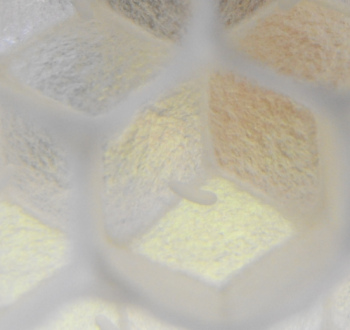

properties too since a closeup look at biochar makes it look like a

tiny sponge.

I've posted previously about

the benefits

of biochar, but how

does biochar actually cause those increases in crop yield? It's

probably easiest for the average gardener to understand that the

increase in pH is caused by the ash that inevitably comes along for the

ride --- using wood

ashes to increase the alkalinity of (or "sweeten") soil is common

wisdom among farmers. And we can visualize the water retention

properties too since a closeup look at biochar makes it look like a

tiny sponge.

The complexities come in

when you start thinking of the chemistry involved. Since biochar

is negatively charged, it naturally attracts anything positively

charged in the soil, and that includes important plant nutrients like

calcium, nitrates, phosphorus, and silicates. This chemical

attraction is why biochar in your soil prevents nutrient leaching --- the minerals are kept in

the root zone rather than washing into the subsoil during heavy rains.

All of these factors

help your plants grow, but probably the greatest benefit of biochar is

its ability to increase the populations of beneficial microorganisms in

the soil. In fact, one study of Amazonian Dark Earth (aka terra

preta) compared to nearby, natural soil showed that the Dark Earth

contained a completely different set of microorganisms than the natural

soil.

Biochar helps many bacteria

and fungi grow because it provides tiny nooks and crannies just big

enough for these microorganisms but not large enough for predator

microorganisms. In their protected dens, the bacteria and fungi

grow like crazy, especially if you make your biochar at a relatively

low temperature so that the insides are coated with energy-rich tars

for them to eat. Scientists have found that arbuscular

mycorrhizae (the fungi that attach to your plants' roots and help them

get hard-to-find nutrients) are especially aided by biochar in the soil.

Biochar helps many bacteria

and fungi grow because it provides tiny nooks and crannies just big

enough for these microorganisms but not large enough for predator

microorganisms. In their protected dens, the bacteria and fungi

grow like crazy, especially if you make your biochar at a relatively

low temperature so that the insides are coated with energy-rich tars

for them to eat. Scientists have found that arbuscular

mycorrhizae (the fungi that attach to your plants' roots and help them

get hard-to-find nutrients) are especially aided by biochar in the soil.

Nitrogen-fixing

bacteria also love

biochar, but for a different reason. The biochar pores tend to

create low oxygen conditions where these anaerobic bacteria

thrive. As a result, legumes create more nitrogen-fixing nodules

when biochar is in the soil and free-living nitrogen-fixing bacteria

also multiply. That means more nitrogen for your plants without

any work on your part.

| This post is part of our Biochar in the Backyard lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

With the golf cart down and

the driveway too muddy for the truck I resorted to the old trusty garden

wagon to haul in the latest round of food

scraps/worm food.

I didn't make it that far

before I realized mud was packing in the wheel well area causing an

increase in the rolling resistance to the point of being dragged parts

of the way.

My solution for now is to use

the wagon as a cage and figure something out tomorrow. Maybe we should

build the new worm bin by the parking area to simplify the operation?

This

is a perfect time of year to assess the state of your freezer (or

pantry) and change your hoarding goals for next year. Every year,

I try to guess how much of each type of produce we should save for the

winter, and every year it seems like our tastes change and I wish I'd

had more of some things and less of others. This winter, our joy

has been harvest

catch-all soup ---

when I'm feeling under the weather or am just in need of a quick meal,

I thaw out two pint-sized servings, add a fried egg or bit of cheese

for extra protein, and the meal is done. Even though I froze

seven gallons of the soup, we could have used more.

This

is a perfect time of year to assess the state of your freezer (or

pantry) and change your hoarding goals for next year. Every year,

I try to guess how much of each type of produce we should save for the

winter, and every year it seems like our tastes change and I wish I'd

had more of some things and less of others. This winter, our joy

has been harvest

catch-all soup ---

when I'm feeling under the weather or am just in need of a quick meal,

I thaw out two pint-sized servings, add a fried egg or bit of cheese

for extra protein, and the meal is done. Even though I froze

seven gallons of the soup, we could have used more.

On the other hand, our pesto

column is nearly untouched. Since we're now exercising a lot more

moderation with pasta, I tend to make lasagna instead of pesto pasta or

spaghetti with tomato sauce. I can use up three quarts of

vegetables in a single pan of lasagna, mix in two cups of flour (turned

into noodles, of course), add a pound of meat and some cheese, and have

a well-rounded, one dish dinner.

On the other hand, our pesto

column is nearly untouched. Since we're now exercising a lot more

moderation with pasta, I tend to make lasagna instead of pesto pasta or

spaghetti with tomato sauce. I can use up three quarts of

vegetables in a single pan of lasagna, mix in two cups of flour (turned

into noodles, of course), add a pound of meat and some cheese, and have

a well-rounded, one dish dinner.

Greens are also going