archives for 03/2010

I

amused myself Sunday morning with a sudoku

puzzle --- figuring out which beds each crop will grow in this

year. The process is actually quite fun, with three axes to

consider --- soil depth, amount of sun, and plant family over the last

three years. As an example, I wanted carrots to grow in an area

with deep soil, where carrots and parsley hadn't grown lately, with any

kind of sun exposure. In contrast, my peas don't mind thinner

soil, but I want them in one of the sunniest spots since I

plant them so early, and of course the bed can't have hosted peas,

beans, or peanuts lately.

I

amused myself Sunday morning with a sudoku

puzzle --- figuring out which beds each crop will grow in this

year. The process is actually quite fun, with three axes to

consider --- soil depth, amount of sun, and plant family over the last

three years. As an example, I wanted carrots to grow in an area

with deep soil, where carrots and parsley hadn't grown lately, with any

kind of sun exposure. In contrast, my peas don't mind thinner

soil, but I want them in one of the sunniest spots since I

plant them so early, and of course the bed can't have hosted peas,

beans, or peanuts lately.

The puzzle was engrossing and fun, but I quickly realized that we don't

have enough beds in rotation to plant all of the veggies I hope to grow

this year. Two years ago, I was

working for a non-profit, trying to keep the garden

going between

writing grants and attending meetings. I was so stressed out,

that when I planned last year's garden, I cut out nearly a quarter of

the growing area. In farmer speak, I let those areas go fallow;

in Anna speak, the weeds grew up.

The downside of last

year's smaller garden is that we didn't

grow quite enough vegetables to make it through this winter.

We'll probably have to buy some veggies in March and April, which is an

unpleasant surprise since we we haven't bought vegetables (beyond

onions and potatoes) in years.

On the upside, I managed to keep the beds that were in rotation last

year well weeded and mulched and started to cut down on the awful weed

population that grew up during my stressed out, non-profit year.

Overall, a year of gardening smaller made sense and was an asset to the

farm (and my sanity.)

Even though I advocate no-till

farming, I never

manage to put down a sheet mulch a

year in advance to start new beds (or re-start fallow

ones.) So, I'm

back to a bit of digging to delete the weeds from last year's fallow

beds. I like to plant potatoes in these

spots, since the tubers necessitate a second round of digging in the

fall, ensuring that few deep-rooted weeds survive the renovation

year.

Even though I advocate no-till

farming, I never

manage to put down a sheet mulch a

year in advance to start new beds (or re-start fallow

ones.) So, I'm

back to a bit of digging to delete the weeds from last year's fallow

beds. I like to plant potatoes in these

spots, since the tubers necessitate a second round of digging in the

fall, ensuring that few deep-rooted weeds survive the renovation

year.

On Sunday, I dug up a

few of the beds, just spading the

soil enough that the chickens could get a foothold, then watched as our

feathered friends went to town scratching up the soil. After a

few days of chicken scratching (and fertilizing), I'll rake the beds to

pull out any big root masses, mound the soil back up, and cover the

renovated beds with a heavy leaf

mulch. This

method has worked very well in the past, as long

as I plant the potatoes on raised mounds --- last year I flubbed by

putting the seed potatoes below the original ground level and watched

them rot in our wet soil. Hopefully this fall, I'll have

delicious potatoes and some newly weed-free beds.

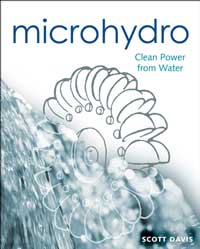

Microhydro:

Clean Power From Water

by Scott Davis is written at a sixth grade reading level...and that's a

good thing. I'm far from ready for an installation guide;

instead, I just wanted to know if microhydro is feasible on our farm.

Microhydro:

Clean Power From Water

by Scott Davis is written at a sixth grade reading level...and that's a

good thing. I'm far from ready for an installation guide;

instead, I just wanted to know if microhydro is feasible on our farm.

Although most people

with an interest in alternative energy go straight to solar cells,

microhydro

can be a much more economical option if your terrain is right.

I've read estimates suggesting that consumer-level microhydro systems

are between 5 and 40 times as cost effective as photovoltaic systems,

in large part because water is much less intermittent than the sun so

you don't need as many batteries.

Scott Davis divides

microhydro systems into five levels, only two of which are of interest

to me. The bare essentials level will run lights and small

appliances (like a microwave, radio, telephone, blender, stereo, and

laptop) while the modern conveniences level adds in efficient

refrigerators, freezers, and well pumps. A microhydro system

running the bare essentials can be put together for as low as $2,000

(or possibly even less if you scrounge some parts) while the modern

conveniences level can cost two to three times that much.

Finally, an alternative energy source that wouldn't put us into debt!

| This post is part of our Microhydro lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Each round

of gravel shoveling yields a few improvements on our technique.

Painters

make conscious choices about their pictures' edges because the edges

play a large role in the painting's impact. Ecologists know that

edges promote a diversity of species, more than can be found in either

habitat which the edge joins.

Painters

make conscious choices about their pictures' edges because the edges

play a large role in the painting's impact. Ecologists know that

edges promote a diversity of species, more than can be found in either

habitat which the edge joins.

I've been pondering

edges as I whack back encroaching Japanese honeysuckle, sassafras saplings, and

brambles along the boundary of our garden. I've noticed that my

vegetables are sensitive to even the slightest bit of shade, and that

the boundary beds closest to the thicket produce about half as many

vegetables as do plants in more interior beds. These brushy edges

also delight the deer, who feel safer encroaching

if they can retreat back out of sight in just a few bounds.

Over the last few years,

we've been beating back the edges, first clipping the woody plants,

then running the chicken

tractors across

them, and finally beginning to mow them into a semblance of a

lawn. I don't believe in lawns for prettiness sake, but I do find

them very useful as a way to keep the forest edges from encroaching on

our garden, and the mixed herb pasture keeps our chickens happy.

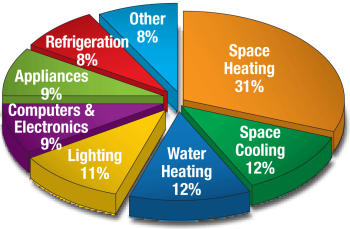

Power usage numbers were the first part of Microhydro that caught my

attention. Scott Davis considers a

system rated at 50 to 100 continuous watts to be the bare essentials

level (running lights and small appliances). This equates to only

35 to 70 kilowatt-hours per month! The

amount of juice put out by even the so-called modern conveniences level

seems

inconceivably low at 75 to 125 kwh/month.

Power usage numbers were the first part of Microhydro that caught my

attention. Scott Davis considers a

system rated at 50 to 100 continuous watts to be the bare essentials

level (running lights and small appliances). This equates to only

35 to 70 kilowatt-hours per month! The

amount of juice put out by even the so-called modern conveniences level

seems

inconceivably low at 75 to 125 kwh/month.For comparison's sake, the average American household uses 936 kwh/month. During our lowest energy month ever (this past June), we came in at 270 kwh. Running a household on 75 kwh/month seems almost inconceivable to me.

But Scott Davis makes the excellent point that artificially low electricity prices in North America have led to extremely wasteful behavior. Specifically, he notes that electricity should never be used for making heat --- since you lose a lot of power every time you convert energy from one form to another, burning coal to make electricity to make heat is a bad idea.

His example household that runs all of the modern conveniences on microhydro deletes any heating appliances from the mix. Clothes driers, of course, are replaced by the good old solar clothesline. Rooms are heated with wood or passive solar while water is heated with solar hot water heaters in the summer and coils around the wood stove in the winter. Finally, cooking is done on propane (or, I would add, on a rocket stove.)

As always, the best and cheapest way to save energy is to become more efficient, so I think we'll do some basic efficiency tricks before saving up for an alternative energy system. Our biggest energy hogs are clearly our electric stove (which heats our water as well as cooks our dinners) and our back-up space heaters, so these seem like a good place to start.

| This post is part of our Microhydro lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Video credit goes to Anna for capturing this 38 second driveway moment.

Next

week, the cuteness quotient of the Walden

Effect will be rising considerably. We ordered 16 chicks as the

first step in solving our chicken

reproduction problem.

The goal is to start a self-sustaining

flock in a forest pasture --- which I'll be explaining in much greater

depth next week on our chicken

blog.

Next

week, the cuteness quotient of the Walden

Effect will be rising considerably. We ordered 16 chicks as the

first step in solving our chicken

reproduction problem.

The goal is to start a self-sustaining

flock in a forest pasture --- which I'll be explaining in much greater

depth next week on our chicken

blog.

After a great deal of research, we settled on the Dark Cornish as this

year's experimental chicken breed. Unlike the white, waddly

Cornish Cross chickens that share their name (and a bit of their

genetics), Dark Cornish chickens are wiley and nearly feral in their

ability to sustain themselves on pasture. They are also very good

at avoiding predators, and one blog even suggested that Dark Cornishes

can kill a marauding fox!

The only disadvantage of the Dark Cornish is that the chickens take

about twenty

weeks to reach cooking size, far longer than most other broilers.

But I've read that their flavor more than makes up for the wait.

If our forest pasture experiment works out, feed costs won't be an

issue, so we're excited to give the new system a shot.

Despite

wanting to consider energy efficiency first, I was still curious

whether the copious water on our farm would be a good fit for

microhydro power. The first step in assessing a site for

microhydro is to measure stream flow. Scott Davis suggests two

easy methods.

The

weir method

is used in

large streams or rivers. The water flows through a notched weir

that forms a waterfall. You can use various tables or formulas to

determine the flow rate of your creek based on the width and depth of

the water in the weir's notch. I didn't feel like constructing a

weir, so I moved on to option 2.

The

container method

consists of finding a spot where all of the creek's water runs through

a culvert or pipe, then sticking a five gallon bucket underneath.

Time how long it takes for your bucket to fill up, then use the

following formula to determine your stream's flow:

As you can see in the

embedded video, I found a spot where a

huge root mass had channeled all of our smaller creek's water into a

waterfall, so decided to try out the container method of estimating

stream flow. I couldn't fit a five gallon bucket under the

waterfall, but a one gallon cook pot slipped right in between the roots

and filled up in 3 seconds. Our flow in that creek is

approximately:

Our

smallest creek's flow is pretty low, but is definitely within the realm

of microhydro power. In fact, Scott Davis notes that you can get

power from streams running as slowly as 2 gpm (gallons per minute.)

| This post is part of our Microhydro lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

There's a really good

wiki-how that sums up what you need to know about sharpening your

chainsaw with a hand file.

It seems the experts suggest

a machine grinding at a shop after every 5 hand sharpening episodes.

You can buy small attachments

for a Dremel to make the job easier, but these little hand files are a

lot cheaper.

Last

year, a couple of friends teamed up and bought us a dozen beautiful blueberry

plants in honor of

our wedding. We were sorely unprepared, so we only managed to

whack down box-elders and open up the canopy, then roll the logs out of

the way and plant the bushes in new ground. This oversight caused

a lot of problems since I couldn't really get the lawnmower around the

logs, and by the middle of the summer, our blueberry patch had turned

into a weed patch. Luckily, the blueberries survived the neglect,

and I promised them a more weeded existence this year.

Last

year, a couple of friends teamed up and bought us a dozen beautiful blueberry

plants in honor of

our wedding. We were sorely unprepared, so we only managed to

whack down box-elders and open up the canopy, then roll the logs out of

the way and plant the bushes in new ground. This oversight caused

a lot of problems since I couldn't really get the lawnmower around the

logs, and by the middle of the summer, our blueberry patch had turned

into a weed patch. Luckily, the blueberries survived the neglect,

and I promised them a more weeded existence this year.

We

spent the morning Wednesday clearing up the tree carcasses in the

blueberry patch to make this year's mowing much easier. Mark's

hard work with the chainsaw netted us half a cord of

firewood, now drying in the woodshed, and my branch piles are growing

too. Our chipper rental date is tentatively set for

this weekend, but Lucy didn't want to wait --- she did her part to

increase the farm's wood chip supply while we cleared the brush.

We

spent the morning Wednesday clearing up the tree carcasses in the

blueberry patch to make this year's mowing much easier. Mark's

hard work with the chainsaw netted us half a cord of

firewood, now drying in the woodshed, and my branch piles are growing

too. Our chipper rental date is tentatively set for

this weekend, but Lucy didn't want to wait --- she did her part to

increase the farm's wood chip supply while we cleared the brush.

The

other important measurement to take when assessing your creek for

microhydro is pressure or head. The two terms are different

measurements of the same thing --- potential energy just waiting to

turn your turbine and make some power.

Many homesteaders pipe

water from a spring down to their house, and the energy in the water

line can be tapped for microhydro power. To measure pressure

directly in such a situation, install a gressure gauge in the line and

read the dial.

If you don't already

have a water line in place, you're better off calculating a stream's

head

rather than measuring pressure directly. Head is simply the

change in elevation between the highest and lowest points of a stream,

and it can be measured in several different ways. If you have a

gps or watch with an altimeter, this can give a rough measurement of

the respective elevations, but I found the water level method (outlined

in the embedded video) to be the

simplest.

To measure head using

the water level method, find an inflexible length of pipe and start at

the stream's highest point. Completely submerge the pipe, then

slowly lift the downhill end out of the water. Creek water will

flow out of the pipe's downhill end until it is raised level with the

uphill end, at which point water will stop flowing. Measure the

vertical distance between the downhill end of the pipe and the ground

and you have the change in elevation between the two points. Now

scoot the pipe downstream until the uphill end rests where the

downhill end used to be, and repeat your measurement. Lather,

rinse, and repeat until you run out of shampoo...er, reach the end of

the stream. The head is the sum of all of the elevations measured

along the creek's length.

The downfall of our

property's creeks is their valley-bottom flatness. Our small

creek has the largest head, and even there the total change in

elevation is

barely over three feet. Granted, microhydro applications can work

with as little as 2 feet of head, but the setup becomes much pricier if

your head is less than 50 feet.

| This post is part of our Microhydro lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We decided to make the new home

made brood coop big enough to handle the little styrofoam incubator

for future chick operations.

The trick will be to monitor the temperature over the weekend to see if

any adjustments need to be made.

I used a few scrap pieces of

2x4 to secure up each corner, which worked nicely as a support for both

Avian Aqua Misers.

Every

morning this week, I've woken up to a light coating of snow on the

ground. The snow cover gently melts off by lunchtime, meaning

that the soil in the floodplain has been too wet to drive on since

Tuesday. As a result, we couldn't haul in loads of manure

from our neighbor to

fertilize the onion beds I need to plant this

week. What could I do?

Every

morning this week, I've woken up to a light coating of snow on the

ground. The snow cover gently melts off by lunchtime, meaning

that the soil in the floodplain has been too wet to drive on since

Tuesday. As a result, we couldn't haul in loads of manure

from our neighbor to

fertilize the onion beds I need to plant this

week. What could I do?

The obvious solution is

chicken manure, but onions like soil high in organic matter and chicken

manure melts into the ground almost like chemical fertilizers.

Clearly, I needed humus. But I wasn't keen on the idea of

carrying heavy five gallon buckets a third of a mile from the parking

area to the garden.

As

I stood peering around me with furrowed brow, I noticed Lucy digging

frantically around a tree stump. Four years ago, we cut down

young forest in the mule garden, but we left the stumps in place since

I refused to let Mark buy dynamite and blow them out. We've been

mowing and working around them ever since.

As

I stood peering around me with furrowed brow, I noticed Lucy digging

frantically around a tree stump. Four years ago, we cut down

young forest in the mule garden, but we left the stumps in place since

I refused to let Mark buy dynamite and blow them out. We've been

mowing and working around them ever since.

I'd forgotten about the

stumps, but Lucy hadn't. She was hard at work rooting out a shrew

at one stump's base. If I'd been in a comic strip, a light would

have gone off above my head at that moment. "Lucy digs for

shrews, shrews love earthworms, earthworms love compost, and I want

compost..."

I pushed Lucy aside, and

ran my fingers through the rich stump

dirt that had been

sitting right in front of my face. Over the last four years, turkey tail fungi

had colonized the stumps and broken the cellulose down into

compost. By digging around at the soil line, I quickly came up

with four beautiful bucket-loads of the soft, fluffy compost.

Thanks, Lucy!

The

final step of assessing your stream for microhydro is doing a bit of

math to determine the creek's power. I'm simplifying a bit here

because you will lose some power due to friction as the water rubs up

against the inside of your pipe, but this formula is good enough for

estimating whether your creek is worth looking into further.

The

final step of assessing your stream for microhydro is doing a bit of

math to determine the creek's power. I'm simplifying a bit here

because you will lose some power due to friction as the water rubs up

against the inside of your pipe, but this formula is good enough for

estimating whether your creek is worth looking into further.

If you'd rather have

your estimated energy output in kwh/month so that you can compare it to

your electric bill, continue on to this formula:

So, it's finally time to

see if our little creek passes the test. She puts out 20 gpm of

water and has a head of about 3 feet. So:

Power output = 20 gpm X 3 ft ÷ 10 = 6 continous watts

Kwh/month = 6 continuous watts X 0.72 = 4.3 kwh/month

Sadly, our little creek

failed miserably --- that would be enough to keep the lights on in our

house, but nothing more. As a rule of thumb, you need either a

large head or a large flow to make microhydro appealing, and our little

creek had neither.

On the other hand, we

have several other possibilities on our property that look more

appealing. If we were willing to pay a lot for a run of the river

system, or to build a big dam, our primary creek would definitely

provide all of our power. On the cheaper side, it's possible that

it would be worth our while to tap energy from the spring that comes

out way up on the hill, although it does stop flowing during dry

weather.

Finally, I'm curious

whether there would be a way to make electricity from the water running

off the barn roof if we installed gutters. I envision using tanks

as a storage system and just letting the water leak out slowly, rather

than buying expensive (and environmentally unfriendly batteries.)

I estimate that nearly 4,000 gallons of water flow off the roof each

month, but I guess that's only 0.09 gpm. Back to the drawing

board....

| This post is part of our Microhydro lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The occasional water line

damage is to be expected when your wife is just starting to learn the

finer points of 40

caliber marksmanship.

While

digging around in the stump

dirt Thursday, I

uncovered some found art. Lucy must have buried a carcass in the

base of the stump because my scrabbling fingers turned up tufts of fur

and leg bones...and then this perfect skull.

While

digging around in the stump

dirt Thursday, I

uncovered some found art. Lucy must have buried a carcass in the

base of the stump because my scrabbling fingers turned up tufts of fur

and leg bones...and then this perfect skull.

I found a very useful key for

identifying mammal skulls and soon discovered the

skull's owner. The answer is after the second picture for those

who want to guess.

The first distinguishing

feature is the large gap between the majority of the teeth and the

incisors, which determines that the animal was either a rodent or a

rabbit. If you look closely below the big incisors at the front

of the jaw, you'll notice two smaller teeth tucked back into the

skull. These peg teeth are used for grabbing or cutting food and

identify my skull as a rabbit.

I find skulls endlessly

fascinating and once had a collection, but eventually learned that

collections bog me down. So I gave this rabbit to our winesap

apple tree as a source of

calcium.

Last week's Arctic

homesteading documentary

really managed to stay with me and inspired a medium sized search for

another similar type story.

That seems like all there is

of the free stuff, but the Homestead National Monument

of America just updated

the movie that plays in their Museum. It's not online yet, but if

you're in or near the Beatrice Nebraska zipcode you might want to plan a visit.

160 acres of land free for

the taking sounds like a good deal, but I'm not sure if I would have

gone for such a dream if I were alive back then. I guess it would

depend on if there were any other options at the time.

The

lettuce I planted a solid month ago in a cold frame is up at long

last. Usually, we would

have been eating the February lettuce by now and would have planted

a bed of March lettuce to eat next month. But this abnormally

cold winter has resulted in abnormally cold soil which sets our seeds

back.

The

lettuce I planted a solid month ago in a cold frame is up at long

last. Usually, we would

have been eating the February lettuce by now and would have planted

a bed of March lettuce to eat next month. But this abnormally

cold winter has resulted in abnormally cold soil which sets our seeds

back.

Luckily, I can tell that

the ground temperatures are finally rising. Not only is the

lettuce up, but our water line has started thawing during the days ---

more signs of spring!

On the bad news side,

I've been overdoing it and my carpal tunnel is flaring up. That

means I don't sleep well, which means I'm grumpy and my head goes wonky

during the day. I apologize if nothing I write makes sense.

This short video provides an

accurate yet boring picture of how the

rental chipper cuts a rug.

Our share ended up being 1/3

of the weekend time which worked out to be

65 dollars.

It was a great opportunity

that would not have been possible without

our neighbors' suggestion of sharing the time and the aid of their

tractor to pull the thing all the way back here. Well worth waking up

early tomorrow morning to drive it back to it's home in the big city.

I imagine this might be the

closest thing we have to participating in

an old fashioned barn raising which is too bad because this neighborly

cooperation thing is a pretty darn good feeling at the end of the day.

Wood

chips make me chipper. What can I

say --- some women like roses, but I like mulch, even if it won't be

properly aged until several months from now.

Wood

chips make me chipper. What can I

say --- some women like roses, but I like mulch, even if it won't be

properly aged until several months from now.

We spent most of the day Saturday over at our neighbors' helping them

chip the biggest pile of saplings I've ever seen. Sunday

afternoon it was our turn. One neighbor drove the chipper over to

our place with his amazingly huge tractor, and then we chipped up a

storm for about four hours before giving in to exhaustion.

Despite

being pleased as punch about our wood chips, I have to admit

that I think the chipper rental won't be an experiment we'll be

repeating. Once I put on my wrist braces, my carpal tunnel

simmered down, but it was still an awfully wearing weekend for about as

many chips as we could get for free if we

hunt down the utility line

guys. Add in a few hours drive to pick up and drop off the

chipper, and we might have been just as well off to buy mulch.

Despite

being pleased as punch about our wood chips, I have to admit

that I think the chipper rental won't be an experiment we'll be

repeating. Once I put on my wrist braces, my carpal tunnel

simmered down, but it was still an awfully wearing weekend for about as

many chips as we could get for free if we

hunt down the utility line

guys. Add in a few hours drive to pick up and drop off the

chipper, and we might have been just as well off to buy mulch.

On the other hand, we did clear up some brushy edges that needed work,

and I have my wood chip piles segregated into partially decomposed (for

mulching with this year), fresh pine (for mulching the blueberries next

year),

and fresh box-elder (for planting mushrooms in.) The control

freak

in me is well pleased. And, look, the year's first crocus!!

As you've probably surmised,

I'm intrigued by traditional methods of gardening and farming. In

previous lunchtime series, I've explored Central

American farming, Chinese

farming, and tropical

forest gardens from around the world. This week I want to

look at a gardening technique that is much less exotic --- British

cottage gardening.

As you've probably surmised,

I'm intrigued by traditional methods of gardening and farming. In

previous lunchtime series, I've explored Central

American farming, Chinese

farming, and tropical

forest gardens from around the world. This week I want to

look at a gardening technique that is much less exotic --- British

cottage gardening.

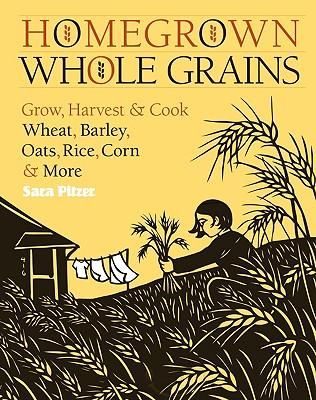

The

Cottage Garden by

Christopher Lloyd is a pretty and chatty book, perfect for flipping

through when you're yearning for spring. It's nearly a picture

book, and doesn't have any in depth information, but the book is a

helpful look at the tradition that helped give rise to Robert

Hart's forest gardening. Cottage gardening

also has something to teach anyone who strives to be self-sufficient.

| This post is part of our Cottage Garden lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Dropped off the rental

chipper bright and early today in Kingsport which happens to be

down the road from the Mulch store.

We bought 2 cubic yards of

double ground, slightly aged mulch for 48 bucks.

Anna got a bit weak in the knees from her first handful and sniff not

unlike the reaction you see when a wine expert gets his or her hands on

a glass of 1943 Chateau Picard.

When

it snowed the first four days of March, I started feeling like maybe we

weren't getting spring this year. But then came four days of

brilliant sun, and our farm now looks completely different.

When

it snowed the first four days of March, I started feeling like maybe we

weren't getting spring this year. But then came four days of

brilliant sun, and our farm now looks completely different.

As I worked more buckets

of stump

dirt into the garden and planted greens, I felt like I was living

in the climax of How the

Grinch Stole Christmas:

It came without droughts!

It came without lettuce,

spring peepers, or sprouts!

And what happened then...?

Well...on our farm they say,

That my tiny winter heart

grew three sizes that day!

Not only did my heart

grow three sizes, I saw two species of butterflies out flitting about

--- the Mourning Cloak I captured in pixels and either a Comma or

Question Mark. The bees were foraging in earnest, though I didn't

take the time to hunt down their quarry. Best yet, Mark got the golf

cart all the way out to the parking area with just a bit of

encouragement. We're back in business!

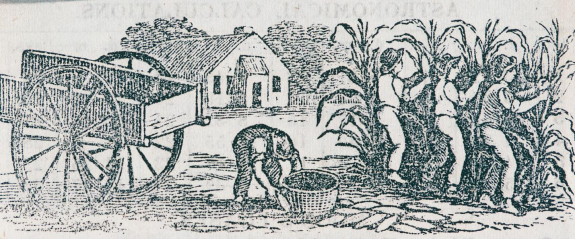

The

cottage garden arose naturally over the last half millenium as British

peasants planted gardens around their small houses. These were

hard-working laborers who didn't have the time or energy to spare for

mere prettiness, so they planted large vegetable, herb, and fruit

gardens, interspersed with a few flowers. The cottage garden

traditionally held a pig sty, a chicken coop, and bee hives as well to

round out the cottager's fare.

The

cottage garden arose naturally over the last half millenium as British

peasants planted gardens around their small houses. These were

hard-working laborers who didn't have the time or energy to spare for

mere prettiness, so they planted large vegetable, herb, and fruit

gardens, interspersed with a few flowers. The cottage garden

traditionally held a pig sty, a chicken coop, and bee hives as well to

round out the cottager's fare.

Around the end of the

eighteenth centuries, these poor peasants were

joined by the first wave of back-to-the-landers. Members of the

gentry began to idealize the cottage life and to create their own

cottage gardens. This is when the cottage garden began to veer

toward prettiness for its own sake, with scads of flowers often

replacing the original mixture of edible plants and animals.

In either case, though,

cottage gardens were beautiful. While the

vegetable patch was usually planted in bare, straight rows, the rest of

the garden consisted of plants pushed together until no soil could be

seen between the leaves. This informal clumping is the signature

feature of the cottage garden and can also be seen in the hodge-podge

of closely packed plants in Robert

Hart's forest garden.

| This post is part of our Cottage Garden lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Total cost on this home made

golf cart dump box was just over 5 bucks thanks to using scrap

wood from the old house.

It expands the back hauling

capacity of the golf cart from 2 buckets to 7, with about 3 buckets

worth in between the cracks.

Next up is a wooden rack to

take advantage of some space up front.

These

are our straight pipes. The operation isn't as environmentally

unfriendly as it sounds since the water only flows from our kitchen

sink, the worst pollutants are a bit of dish soap and toothpaste, and

there's no way any of it can run into the creek. Still, the

cesspool is unsightly, and Lucy likes to drink out of it, which we

highly disapprove of. Time for some mycoremediation!

These

are our straight pipes. The operation isn't as environmentally

unfriendly as it sounds since the water only flows from our kitchen

sink, the worst pollutants are a bit of dish soap and toothpaste, and

there's no way any of it can run into the creek. Still, the

cesspool is unsightly, and Lucy likes to drink out of it, which we

highly disapprove of. Time for some mycoremediation!

This is a hunk of King

Stropharia (aka Winecap) sawdust spawn. When we put in our

mushroom order this winter, I asked Mark if we could experiment with a

five pound bag of this new species. I told him how King

Stropharia is great at filtering graywater and is also a food source

for honeybees.

But Mark still seemed displeased by my order. "Should I back off

to two pounds?"I asked. "Nope," Mark countered. "Double

it! Double it!"

Stropharia is great at filtering graywater and is also a food source

for honeybees.

But Mark still seemed displeased by my order. "Should I back off

to two pounds?"I asked. "Nope," Mark countered. "Double

it! Double it!"

Just

in case you're curious, ten pounds of King Stropharia sawdust spawn is

enough to innoculate just over a cubic yard of wood chips. I

broke the spawn down into two pound sections so that I could innoculate

several smaller beds. First, I mounded up our fresh wood

chips to a depth of

about six inches, then I crumbled up the appropriate amount of sawdust

spawn to put on top. I covered the spawn with about an inch of

additional woodchips to protect it from drying out, then set up the

sprinkler and soaked the whole operation for a while. I'll need

to check every day for the next few weeks to make sure the mushroom

beds stay damp, watering them as necessary. Then there's no work

involved until the mushrooms appear this summer.

spawn to put on top. I covered the spawn with about an inch of

additional woodchips to protect it from drying out, then set up the

sprinkler and soaked the whole operation for a while. I'll need

to check every day for the next few weeks to make sure the mushroom

beds stay damp, watering them as necessary. Then there's no work

involved until the mushrooms appear this summer.

In addition to our

graywater filtration bed, I'm experimenting with four other

locations. Three are under the canopy of our young peach and

nectarine trees, and the fourth is out in the open but in a very damp

spot. Hopefully the spawn will take hold in at least one bed so

that next year we'll know what optimal King Stropharia habitat looks

like.

The

traditional cottage garden had to be enclosed by a fence, hedge, or

wall to prevent wandering sheep from eating up the plants. Of

these three options, a hedge

was the most traditional enclosure since it was cheap and relatively

easy to create. A well developed hedge kept livestock and wind

out of the garden with ease.

The

traditional cottage garden had to be enclosed by a fence, hedge, or

wall to prevent wandering sheep from eating up the plants. Of

these three options, a hedge

was the most traditional enclosure since it was cheap and relatively

easy to create. A well developed hedge kept livestock and wind

out of the garden with ease.

Traditional British

hedges often contained a mixture of native trees,

roses, hazelnuts, blackberries, forsythia, quince, damsons, and

hawthorns. Christopher Lloyd noted that hedges did double-duty,

both keeping out unwanted livestock and providing edible plants without

taking up valuable garden space. The hedges did require trimming

once or twice a year, but that was a small price to pay for free and

tasty fencing.

| This post is part of our Cottage Garden lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Today I discovered that 7

buckets of manure in the back with 3 buckets riding shotgun and 2

buckets of gravel on the floor board is about the load limit for the

new home

made golf cart dump box.

I can't believe it took us

this long to make such an obvious improvement in carrying capacity.

Huge pink buds under the

leaf

mulch give way to

pale yellow leaves --- the rhubarb is ready to grow. I rake

autumn leaves off the rhubarbs, strawberries, and asparagus to give my

early risers an opportunity to bask in the early spring sun.

Within minutes, I count two salamanders, half a dozen spiders, and

innumerable worms. It may just be my imagination, but the soil

seems more alive than in mulchless Marches. Once my plants spread

out a bit, I'll push the dead leaves back underneath as mulch, but for

now I don't want my perennials to fade away from lack of sunlight.

Meanwhile, with our

freezer nearly empty, I'm eying those rhubarb buds with

uncharacteristic glee. I'm ashamed to say that even though I've

had a very healthy patch for years, I don't think I've eaten a

stalk. What's your favorite rhubarb recipe? (Not

strawberry-rhubarb pie --- I consider any cooked form of strawberries a

waste of their vibrant goodness.)

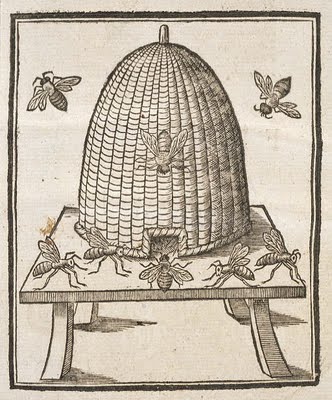

I

can easily imagine how a beehive would be an essential part of a

cottager's garden since they probably had no other source of

concentrated sugar. Due to the ubiquity of bees in the cottage

garden, Christopher Lloyd's The

Cottage Garden contains a whole section on bee-attracting plants.

I

can easily imagine how a beehive would be an essential part of a

cottager's garden since they probably had no other source of

concentrated sugar. Due to the ubiquity of bees in the cottage

garden, Christopher Lloyd's The

Cottage Garden contains a whole section on bee-attracting plants.

Christopher Lloyd

recites the common wisdom that the mint and aster

families are bee favorites, but goes on to add several other species

that are a must for bee habitat. Crocuses and willows are on his

list as good sources of early spring pollen, allowing the hive to

quickly build up their numbers so that they'll be ready for the

summer rush. Speaking of the summer rush, Hydrangea

villosa,

basswood, borage, fennel, thyme, sage, clematis, and white

clover are

all given pride of place as bee-friendly summer flowers. Finally,

Christopher Lloyd notes that fall-blooming Sedums are important

nectar-providers.

I tend to overlook

flowers in the garden, but will have to consider

adding some of these top bee plants to nooks and crannies over the next

few years.

| This post is part of our Cottage Garden lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I really enjoyed the recent

interview with Frank

Aragona on the Diet

Soap podcast.

Frank goes into some detail

about a new project he's working on with a group in New Mexico that

wants to expand a program that teaches gardening skills to school

children.

It's a concept that is long

overdue and I can't help but to feel like a couple of hours working in

the dirt might actually help to calm down some of the more energetic

students that can never seem to stay in their seats.

I would take it a step

further and teach the kids some basic janitorial skills and put them to

work cleaning the school like students do in Japan.

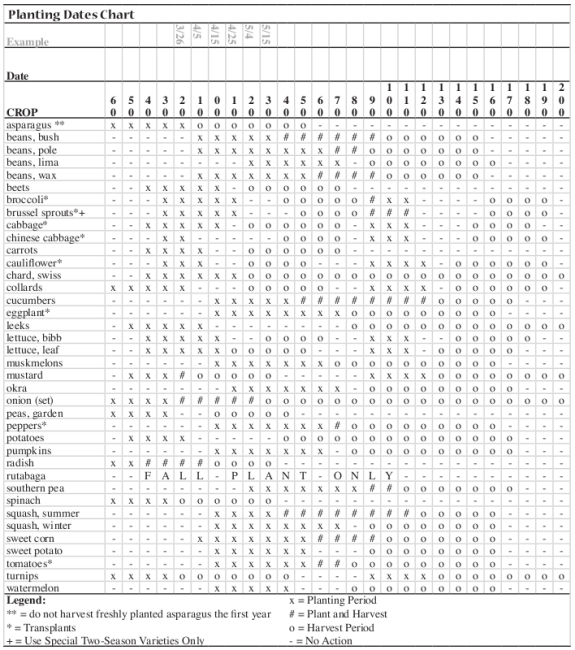

One

of the most common questions I hear from new gardeners is, "When should

I plant my first spring vegetables?" I'm not surprised that folks

are confused since there seem to be several schools of thoughts on the

matter.

One

of the most common questions I hear from new gardeners is, "When should

I plant my first spring vegetables?" I'm not surprised that folks

are confused since there seem to be several schools of thoughts on the

matter.

Around here, many people

plant by the signs. You pick up a calendar at the local hardware

store with phases of the moon and planting dates on it, then put your

seeds in the ground when the moon dictates. People who plant by

the signs also tend to believe that you need to put in your fence posts

at a certain phase of the moon, but I've yet to meet anyone who set up

a controlled experiment to test the effects of the moon's phase on

their garden. I dismiss planting by the signs as voodoo, although

I would like to see some scientific data one way or the other.

The next faction is the

scientific set, of which I'm partially a member. They figure out

their local frost free date (May 15 here in the mountains of southwest

Virginia) then download a spring planting chart and use some simple

math to figure out their planting dates. The chart below comes

from the Virginia Cooperative Extension, and I've posted an

explanation of how to use it here. Note that the example

assumes a frost free date of April 15.

I used a chart like this

to make a spreadsheet with optimal planting dates on it, but I don't

mark the exact dates on my calendar. Our seasons can be so

variable that I suspect the best way to figure out optimal planting

dates is to pay attention to natural signs, like when the first chorus

frogs begin to call or when certain flowers bloom. These plants

and animals are more alert to the intricacies of soil and air

temperature than we are, and chances are they know best.

Unfortunately,

I haven't got this method really figured out yet, beyond the old saying

that you'd best plant your corn when the oak leaves are as big as a

squirrel's ear. So, for now, I just add in a one week window on

either side of the "optimal planting dates" to allow for rain, drought,

strange freezes, or warm spells. For example, although I'm slated

to plant our main crop of peas next week, we rushed and put them in the

ground on Thursday morning before the rain came. The ground is

warm enough that my hands don't freeze as I pull weeds, and the less

clayey areas are actually drying up on top (though some of the clayey

beds would have liked a few more days to evaporate winter's

moisture.) I figured I'd be better off putting my peas in the

ground now than waiting until the ground is dry again, which may not

happen for over a week.

Unfortunately,

I haven't got this method really figured out yet, beyond the old saying

that you'd best plant your corn when the oak leaves are as big as a

squirrel's ear. So, for now, I just add in a one week window on

either side of the "optimal planting dates" to allow for rain, drought,

strange freezes, or warm spells. For example, although I'm slated

to plant our main crop of peas next week, we rushed and put them in the

ground on Thursday morning before the rain came. The ground is

warm enough that my hands don't freeze as I pull weeds, and the less

clayey areas are actually drying up on top (though some of the clayey

beds would have liked a few more days to evaporate winter's

moisture.) I figured I'd be better off putting my peas in the

ground now than waiting until the ground is dry again, which may not

happen for over a week.

Of course, the real

reason I planted our main crop of peas early is because I talked to my

garden guru on Monday and she'd just planted peas in her own

garden. Gotta keep up with the Joneses!

I

wrote earlier that traditional

cottage garden plants were primarily

edibles or medicinals,

but some flowers were included just for

prettiness. Cottagers couldn't afford to buy flowers, but they

often dug up pretty wildflowers to transplant into their garden, or

traded plants with their neighbors. The flowers in a traditional

cottage garden sound exactly like the flowers I allow in my garden ---

they were easy to propagate and often self-sowed, needing little care.

I

wrote earlier that traditional

cottage garden plants were primarily

edibles or medicinals,

but some flowers were included just for

prettiness. Cottagers couldn't afford to buy flowers, but they

often dug up pretty wildflowers to transplant into their garden, or

traded plants with their neighbors. The flowers in a traditional

cottage garden sound exactly like the flowers I allow in my garden ---

they were easy to propagate and often self-sowed, needing little care.

The close spacing of

flowers in the cottage garden helped minimize the

amount of time the cottager spent weeding since the flowers choked out

any weeds. Forest gardeners use this same technique, talking

about filling all unoccupied niches so that unwanted plants don't have

any space to gain a foothold.

I'm unlikely to focus on

flowers anytime soon, but I have started setting aside patches for

self-seeding annuals like cosmos and fennel and have some spring bulbs

that require very little care. I like to think that my garden is

more closely akin to the traditional cottage garden than modern

"cottage gardens" are, complete with fruit trees, herbs, lots of

vegetables, bees, and chickens. All I need is a pig.

| This post is part of our Cottage Garden lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Before

picking up our latest load of

mulch I lined up all the

5 gallon buckets we had in the center of the bed.

Before

picking up our latest load of

mulch I lined up all the

5 gallon buckets we had in the center of the bed.

I was a bit curious to know

if they would stay in place or get knocked over by the force of the

load.

Now that I know it works we

plan to add another 10 buckets before the next load.

With the driveway finally dry enough to drive

over, Mark spent most of his time this week hauling

in load after load of soil amendments. In the process, I've

been learning to visualize a much larger unit of measurement than I'm

used to --- a cubic yard. Obviously, a cubic yard is a volume

that's three feet on each side, equal to 27 cubic feet. That's

equivalent to about 40 five gallon buckets, or half of Joey's pickup

truck bed.

With the driveway finally dry enough to drive

over, Mark spent most of his time this week hauling

in load after load of soil amendments. In the process, I've

been learning to visualize a much larger unit of measurement than I'm

used to --- a cubic yard. Obviously, a cubic yard is a volume

that's three feet on each side, equal to 27 cubic feet. That's

equivalent to about 40 five gallon buckets, or half of Joey's pickup

truck bed.

By my estimate, we

netted two cubic yards of wood chips during our chipper

rental weekend, for a cost of about $33 per cubic yard (not

counting our time and gas.) Ten pounds of King

Stropharia spawn used up a full cubic yard of those fresh chips,

with the other cubic yard set aside for later.

On his way home, Mark bought two

cubic yards of well composted wood mulch, for a cost of $24 per

cubic yard. The mulch covered the ground around a dozen

blueberries, eight grapes, and about seventy linear feet of

blackberries and raspberries. The seemingly huge amount of mulch

was perhaps a third of what I use on my woody perennials each year (and

maybe a tenth of what I could easily put to use if I had an unlimited

supply.)

When I sent Mark over to the neighbors' to shovel up some

of their horse manure, I decided to translate the five gallon

buckets into cubic yards for comparison. He filled up the truck

with twenty buckets of well composted manure, which is about half a

cubic yard. That scantily covered twenty garden beds.

In fact, I put the manure into the garden nearly as fast as Mark could haul it

in to me, and figure I will need at least 5 cubic yards of

compost/manure to feed the vegetable garden this year (and could use

twice that much or more without overfertilizing.)

When I sent Mark over to the neighbors' to shovel up some

of their horse manure, I decided to translate the five gallon

buckets into cubic yards for comparison. He filled up the truck

with twenty buckets of well composted manure, which is about half a

cubic yard. That scantily covered twenty garden beds.

In fact, I put the manure into the garden nearly as fast as Mark could haul it

in to me, and figure I will need at least 5 cubic yards of

compost/manure to feed the vegetable garden this year (and could use

twice that much or more without overfertilizing.)

I'm not quite sure where

I'm going with this thought, except to say that I really like soil

amendments, and I could use many, many cubic yards of them. I

guess I just like to keep track so that we can work up to providing all

of the mulch and compost our farm needs.

I recently discovered that 1

in every 10,000 chickens turns out to be gynandromorphous, half hen,

half rooster, thanks to a recent

BBC article.

Dr Michael Clinton of the

Roslin Institute has just published some of the latest research on the

subject in the scientific journal Nature.

They came up with a

surprising conclusion. The system is different from mammals in that

there is no mutation and the birds are full male on one side and full

female on the other.

Of course the hope is to find

a way to increase production in the poultry business by making female

birds with the same growth characteristics as the male to "increase

productivity and food security".

I don't think I've ever been

happier to see rain in March than I was

this weekend. After our cold, wet winter, a week of sunny days in

the fifties and sixties was irresistable and it took the rain to remind

me that working from dawn until dark every day requires intermittent

days of rest.

The frogs were happy to

see wet weather reappear as well. Spring Peepers and

Chorus Frogs were joined by dozens of Wood Frogs (captured in the

embedded video) by Friday night. Ever since the first spring when

I hunted them

down by flashlight, I've had a very soft spot in my heart for Wood

Frogs --- hopefully you'll see the appeal too.

In researching designs for

our future chicken pasture coop I came across a great collection of

photos detailing the construction of what might be the sturdiest

chicken coop ever built.

I really like it when a

project can be broken down into a series of pictures, and Suburban

Chicken.org did a great job documenting their new chicken palace.

They use that same level of

detail to describe their varied flock of beautiful hens of which I seem

to be partial to Mabel...the one in the bottom right hand corner. It's

a good collection of data on various breeds, but I wonder how brutal

the pecking order is in such a diverse crowd? The more experience I get

with chickens the more I'm inclined to believe the old cliche "birds of

a feather flock together" which is why we've decided to go with just

one breed for the pasture experiment.

Is it cruel to segregate

chickens is such a way? I guess I don't know the answer to that

question, but when I see one chicken being a bully to another it tells

me that the stress level is going up for that one bird which means its

health and egg production might decline in direct relation.

The runner-up question,

after "When

should I plant my first spring vegetables?"

is always "What is my frost free date?" I have to admit that

frost free dates are unimaginably vague, and if you ask three different

people, you'll probably get three different answers. For goodness

sake, I asked two different extension agents (supposedly your best bet

for local information) and got two different answers.

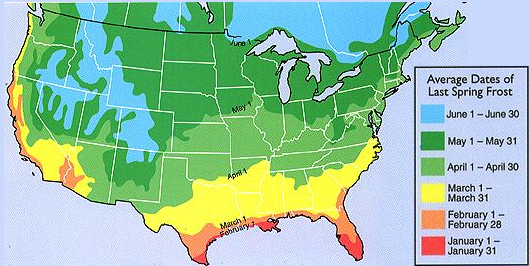

Officially, you can use

the frost-free map reproduced above (which seems to think we're frost

free somewhere between April 1 and April 30) or city

tables like this one

(if you happen to have a city in your vicinity, which we don't.)

No matter where you find your local frost-free date,

you should be aware that microclimate effects mean everything in the

changeable spring. If you live on a north-facing slope, you may

really be one zone colder than if you lived on the south-facing slope

across the valley. If you live near a large body of water or in

an asphalt-laden city, you

may be one zone warmer than if you lived just a few miles away.

Higher elevations, of course, will also be colder than lower elevations

(although many mountains have frost lines with apple orchards safely

protected at the higher elevations from late spring frosts.)

The best way to know

your frost-free date for sure, of course, is to start keeping a weather

journal. Last year, we had a frost

on May 18, so I'm

sticking with my May 15 prediction and ignoring folks who think we're

frost free any earlier.

One

of the most popular topics among homesteaders is alternative

energy. We've done some thinking in that direction ourselves (and

recently posted a series on assessing your

site for microhydro.)

Unlike gardening, though, which is largely intuitive, really

understanding alternative energy requires some grounding in

physics. My high school physics is unbelievably rusty, and I

suspect many of our readers may be equally out of practice, so I

thought it would be a good idea to bring us back up to date in a

lunchtime series.

One

of the most popular topics among homesteaders is alternative

energy. We've done some thinking in that direction ourselves (and

recently posted a series on assessing your

site for microhydro.)

Unlike gardening, though, which is largely intuitive, really

understanding alternative energy requires some grounding in

physics. My high school physics is unbelievably rusty, and I

suspect many of our readers may be equally out of practice, so I

thought it would be a good idea to bring us back up to date in a

lunchtime series.

This is where Roland

came to the rescue. Regular commenters have

probably noticed lengthy, well-thought out comments by Roland in the

past, often correcting our engineering mistakes. (Oops.)

Roland is a design and manufacturing engineer in the Netherlands, and

when I asked him if he might be interested in writing a lunchtime

series about energy, he quickly whipped off a primer on the physics of

energy sources. I have to admit that I'm beyond impressed at his

writing skills since English is not his first language --- I barely

cleaned up what he wrote at all. If you're similarly enthused,

maybe we can tempt him to write another series for us in the near

future.

| This post is part of our Energy Primer lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

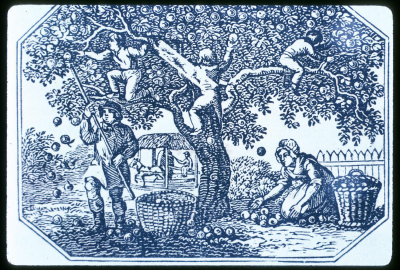

Starting up the deer deterrents is our newest

spring time tradition.

I've learned the hard

way that if our woody perennials aren't taken care of before spring

gets underway, they are quickly pushed to the end of the list and lost

in the shuffle. Last year, a third of our raspberries never got

pruned, fertilized, or mulched, and as a result their fruits were half

the size of the more tended patch. So, this week we're going to

focus on perennials and get them all sorted out and ready to taken on

2010.

I started on Monday by

pruning the fruit trees. In past years, I've spent hours out

there, looking back and forth between my trees and the pruning section

of my master gardener handbook. But this year --- my fourth year

of pruning --- I suddenly felt empowered and able to make short work of

the tree pruning. It helped that last year's summer

pruning and training

had left the trees in really good shape, so my "pruning" mostly

consisted of retying my training strings a little further out on the

branches, with a snip here and there to take out dead wood,

watersprouts, or crossing shoots.

I'm also starting to get

the hang of the two systems I'm using. I'm training our peaches

and nectarine to the open center system and our plum, cherry

(pictured at the top of the page), apples, and pears to the central

leader system. I still don't know if my pruning method is right, but at least it's starting

to become consistent from year to year.

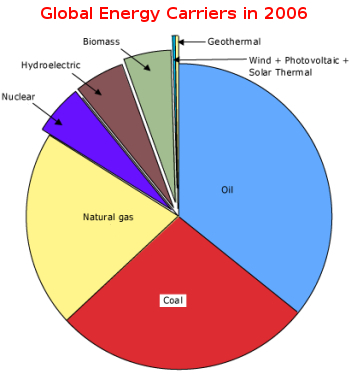

Before we speak about energy, it is useful to lay some groundwork to

understand it better. Most people, when talking about energy sources, are

really talking about energy carriers. Think about gasoline, coal, ethanol,

water, wind. Where does their energy actually come from?

Before we speak about energy, it is useful to lay some groundwork to

understand it better. Most people, when talking about energy sources, are

really talking about energy carriers. Think about gasoline, coal, ethanol,

water, wind. Where does their energy actually come from?

The conservation of energy law and the first law of thermodynamics state that energy cannot be created or destroyed. It can only change form. Einstein showed that mass and energy are equivalent, leading to the famous equation E=mc².

So physically, there are no "sources" of energy, because it doesn't just come into existence. It just looked that way to us before we understood what energy is. What we see as an energy source is just energy being taken from a carrier and transformed from one sort into another. But since the use of the word "source" is so ingrained, I'll not confuse you be being a stickler for accuracy.

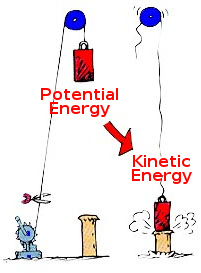

While it is possible for most kinds of energy to be transformed into other

kinds without loss (e.g. dropping something converts potential energy into

kinetic energy perfectly), it is impossible to convert thermal energy into

other forms with 100% efficiency. This is usually called the

second law of thermodynamics; systems tend to evolve towards larger

entropy.

While it is possible for most kinds of energy to be transformed into other

kinds without loss (e.g. dropping something converts potential energy into

kinetic energy perfectly), it is impossible to convert thermal energy into

other forms with 100% efficiency. This is usually called the

second law of thermodynamics; systems tend to evolve towards larger

entropy.

In mechanical systems, friction usually consumes a part of the energy put into the system, and dissipates it as heat. That is why machines are not 100% efficient. The ubiquitous ball bearing uses rolling resistance to reduce friction. But by using fluid bearings it is possible to reduce friction considerably more. Small machines are usually less efficient than big ones.

This work

is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

| This post is part of our Energy Primer lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Where do you get a belt for a

wringer washer

that went out of production during the Nixon administration?

The local auto parts store of

course. Just take in the old belt and ask the nice person behind the

counter if they can patiently size it up with the masses of belts they

stock or tell them you want a Dayco GPL Premium V-belt model number

L432 which is what I ended up with.

Trick

number one for growing great blackberries is choosing the right variety

for your climate. Daddy gave me some starts of his Navaho and

Arapaho berries that grew like gangbusters in his South Carolina

garden, but they were a bust here.

Trick

number one for growing great blackberries is choosing the right variety

for your climate. Daddy gave me some starts of his Navaho and

Arapaho berries that grew like gangbusters in his South Carolina

garden, but they were a bust here.

After three years with

no fruits, I ripped Daddy's berries out and replaced them with

some unnamed blackberries from the midwife who delivered my

sister. My new blackberries produced huge, beautiful

berries...and also extended their primocanes for twenty feet along the

trellis in each direction. Now that's a blackberry that likes our

climate!

Since

I neglected to summer tip the blackberries at three feet tall to

promote branching, my winter pruning involved cutting out last year's

dead canes and then whacking off about 75% of the living canes. I

didn't have the heart to prune them quite as hard as I probably should

have --- the photo above is the after

pruning shot.

Since

I neglected to summer tip the blackberries at three feet tall to

promote branching, my winter pruning involved cutting out last year's

dead canes and then whacking off about 75% of the living canes. I

didn't have the heart to prune them quite as hard as I probably should

have --- the photo above is the after

pruning shot.

Several of the

canes had touched the ground and produced massive root structures, and

I dug up about a dozen of the best ones to expand my blackberry

patch. I also cut the tops off the everbearing raspberries,

pruned out the old floricanes on the other raspberries, trained the

grapes onto their trellises, and cut out the dead bits on the

blueberries. Our woody perennials are now all pruned --- a good

thing too since the blueberries are already thinking of leafing out.

So where does the energy we use actually come from?

So where does the energy we use actually come from?

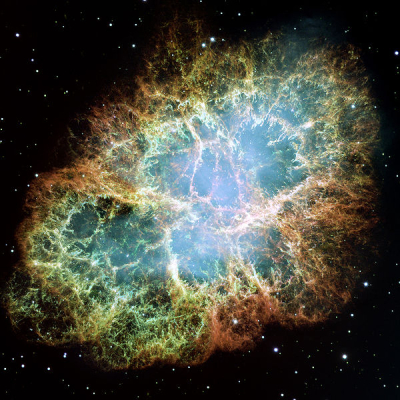

Radiation

In stars, hydrogen atoms undergo fusion producing helium. A very small part of the mass of these atoms is converted into energy which emanates from the sun as radiation. This is one of the two basic energy sources.

Fissionable elements

The other primary energy source is also formed in stars, but in a different way. When a star

substantially bigger than our sun runs out of fuel, its core collapses and the

star explodes in a process called a supernova. During this process, very

heavy elements can be formed that release energy when they are split. These

are called fissionables, and they are the second primary energy source.

One should realize that nuclear fission happens naturally in every fissile

material. This is known as nuclear decay. Without this process we could

not exist, since it is this process that is largely responsible for the fact

that the earth's core is still liquid, which helps to keep us warm and

generates a magnetic field that protects us from cosmic radiation. The heat

flow from nuclear decay inside the earth is around 30 [tera][]watt. (30 000

000 000 000 Watt!)

One should realize that nuclear fission happens naturally in every fissile

material. This is known as nuclear decay. Without this process we could

not exist, since it is this process that is largely responsible for the fact

that the earth's core is still liquid, which helps to keep us warm and

generates a magnetic field that protects us from cosmic radiation. The heat

flow from nuclear decay inside the earth is around 30 [tera][]watt. (30 000

000 000 000 Watt!)

At least one instance has been found where a natural nuclear fission reactor has existed and run for a few hundred thousand years.

This work

is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

| This post is part of our Energy Primer lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Bio char toilet composter is

just a fancy name for a portable out house structure in a strategic

location near a fruit tree.

The bio char element comes

into play by having a bucket of charcoal and leaf matter on hand to be

mixed in the composting section for maximum fertility.

Stay tuned for a more

detailed break down and the final construction pictures.

Biochar

(aka terra

preta)

is the new darling of organic gardeners.

Everyone's talking about it, and no wonder since terra preta in the

Amazon has turned poor ground into high fertility soil that seems to

last hundreds of years without any additional input of fertilizer.

Biochar

(aka terra

preta)

is the new darling of organic gardeners.

Everyone's talking about it, and no wonder since terra preta in the

Amazon has turned poor ground into high fertility soil that seems to

last hundreds of years without any additional input of fertilizer.

What most people don't

realize, though, is that biochar is

more than just charcoal buried in the ground. Amazonians probably

stumbled upon the mixture accidentally when they combined human waste,

crop residue, charcoal from their cooking fires, animal bones, and

plain old trash in their midden heaps. Scientists aren't quite

sure why the resulting mixture is so good for plant growth, but until a

biochemist tells me otherwise, I'm going to assume that all of the

traditional elements are necessary to create true biochar.

Mark and I have decided to

experiment with our own biochar

composting toilet as

a method of adding fertility to our young forest

garden.

Our first incarnation is simply a four foot pit dug in the

ground. We'll poop in the hole and intersperse our humanure with

leaves, charcoal and ashes from the woodstove, and the poultry bones we

need to hide from Lucy. Presumably, the nearby fruit trees will

begin to send their roots into the terra preta as it ages and will get

a good meal. Meanwhile, our system won't require us to handle the

humanure at all, unlike most composting toilet systems, so there's

absolutely no risk of contamination. Maybe the biochar composting

toilet will replace composting toilets in the near future.

Remember how energy can neither be created nor destroyed, only transformed from one type to another? The primary sources of energy in the stars are transformed on earth into the various energy carriers you are probably more familiar with.

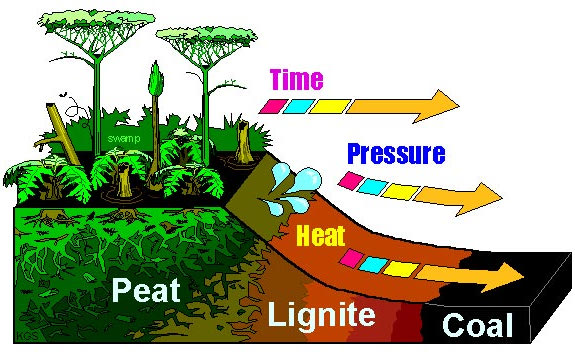

Fossil fuels

These are (hydro)carbons (i.e. chemicals mostly built up out of hydrogen and carbon) formed by anaerobic decomposition of buried dead organisms, over geological timescales. Organisms can be plants, or creatures that feed on plants, or creatures that feed on other creatures. If you follow the chain back, you'll come to plants collecting solar energy and using it (via a process known as photosynthesis) to convert carbon dioxide into organic compounds, mainly sugars.

So essentially, fossil fuels are chemically stored solar energy! The problem with fossil fuels is that we're currently using them at a much faster rate than they are formed. Meanwhile, the carbon dioxide released by burning them influences the climate.

Wood and other plant matter

Since these were the basis for fossil fuels, they hardly need explaining. If they aren't dried before burning, a substantial part of their energy will be consumed by evaporating the water in them. The energy in this water vapor is usually not captured and is lost.

Ethanol

Ethanol can be made via fermentation or as a petrochemical via the hydration of ethylene. Of course, only ethanol produced by fermentation can be considered carbon-neutral.

Fermentation is the process where sugars from plants are converted into ethanol by yeasts. The sugars in the plants, again, are formed by photosynthesis.

The problem with this process is that it results in a lot of biomatter that is of no use to the fermentation process. For example only the grain seeds can be used for ethanol production. Most of the plant is useless in this way. Producing cellulosic ethanol would make this process much more sufficient. Another worry is that growing plants to produce ethanol might hurt food production.

But again, the root source of the energy embodied in ethanol is the sun.

Biodiesel / vegetable oil

These are lumped together because biodiesel is usually made from vegetable

oils or used cooking oil, via a process called transesterification. These

oils are pressed from seeds or fruits or beans of plants. The main reason to

make biodiesel is that diesel engines usually require modifications to run on

straight vegetable oils, while biodiesel requires little to no modification of

a diesel engine.

These are lumped together because biodiesel is usually made from vegetable

oils or used cooking oil, via a process called transesterification. These

oils are pressed from seeds or fruits or beans of plants. The main reason to

make biodiesel is that diesel engines usually require modifications to run on

straight vegetable oils, while biodiesel requires little to no modification of

a diesel engine.

As with ethanol, only a small part of any plant can produce oil. And the same oils that can be used for biodiesel are also used as food. The process uses a strong base like NaOH or KOH as a catalyst, and produces glycerin as a by-product.

Since it is made from plants, the real energy source is again the sun.

This work

is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

| This post is part of our Energy Primer lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I thought it was finally time

to give some photographic credit to the two horses that provide most of

the organic material for our garden.

When

the sun came out Thursday morning, so did

the honeybees. For the first time this year, they seemed to be

deep into a pollen

or nectar flow of

some sort --- there were aerial

traffic jams as the bees piled up, trying to make it through the little

hole in the entrance

reducer.

Honestly, I'm not sure what their

primary food is right now, since I've seen them on the crocuses (more

in the embedded video) and on the tiny speedwell, dead nettle, and

chickweed flowers in the yard. I suspect there may be something

much larger blooming out in the woods to account for this much traffic

--- maybe those swollen elm or hazel buds have burst open?

When

the sun came out Thursday morning, so did

the honeybees. For the first time this year, they seemed to be

deep into a pollen

or nectar flow of

some sort --- there were aerial

traffic jams as the bees piled up, trying to make it through the little

hole in the entrance

reducer.

Honestly, I'm not sure what their

primary food is right now, since I've seen them on the crocuses (more

in the embedded video) and on the tiny speedwell, dead nettle, and

chickweed flowers in the yard. I suspect there may be something

much larger blooming out in the woods to account for this much traffic

--- maybe those swollen elm or hazel buds have burst open?

So much for the outside of

the hive --- what's

going on inside? Once the day was thoroughly warm, I went ahead

and opened up the hives to see how the end of winter was treating the

colonies. I found tiny white eggs, grub-liked larvae, and capped

cells of pupae in two of the hives, along with scads of leftover

honey. I took out the entrance reducers and popped a new super on

each hive just in case the bees get really industrious before I check

back.

So much for the outside of

the hive --- what's

going on inside? Once the day was thoroughly warm, I went ahead

and opened up the hives to see how the end of winter was treating the

colonies. I found tiny white eggs, grub-liked larvae, and capped

cells of pupae in two of the hives, along with scads of leftover

honey. I took out the entrance reducers and popped a new super on

each hive just in case the bees get really industrious before I check

back.

The queens are clearly

just starting to lay their eggs, but I saw a

troublesome sign in one hive. The bees had extended three of the

larvae's cells out beyond the comb's normal face --- it looks to my

untrained eye like they're thinking of building queen cells. That

would mean that I let the hive get too congested with honey and the

bees are thinking of swarming. I'll check on them again next week

and, if necessary, split the hive in two to keep all of the bees under

domestication.

I

also found a tiny cluster of eleven starved

bees. The poor things were face down in adjacent cells, searching

for honey. I've read that little

starvation clusters like this happen when a sudden cold snap strands

some of the bees outside the main cluster. They can't find the

frames of honey, even though food can be quite nearby. Still, a

death toll of less than a dozen bees is not bad since most beekeepers

lose a

third of their hives over the winter. Our chemical-free hives are

still happy and healthy.

I

also found a tiny cluster of eleven starved

bees. The poor things were face down in adjacent cells, searching

for honey. I've read that little

starvation clusters like this happen when a sudden cold snap strands

some of the bees outside the main cluster. They can't find the

frames of honey, even though food can be quite nearby. Still, a

death toll of less than a dozen bees is not bad since most beekeepers

lose a

third of their hives over the winter. Our chemical-free hives are

still happy and healthy.

Water

Very simply put, everything that sits at a higher altitude in a gravitational field has potential energy. The trick is to convert that potential energy into something we can use, like e.g. kinetic energy that we can use or convert into electrical energy. Kinetic energy is the energy embodied into something that is moving.