archives for 02/2010

I've

been a bit quiet on the garden front lately because now is really the

time for dreaming, not for growing. But the garden is actually in

much better shape than any previous winter garden I've been in charge

of, so I thought I'd take you on a quick tour.

I've

been a bit quiet on the garden front lately because now is really the

time for dreaming, not for growing. But the garden is actually in

much better shape than any previous winter garden I've been in charge

of, so I thought I'd take you on a quick tour.

It's quite possible to

have some greens and lettuce even in the dead of winter around here as

long as you start them in the early fall and the deer don't get

them. In previous years, the deer have always eaten my greens to

the ground, but Mark's deer deterrents are worth their weight in

gold! This year we still have some kale and mustard hanging on

--- just enough to put half a cup in potstickers every week or two. (No

lettuce because I planted it late and didn't get it up to speed in

time.)

I've

always read that you can eat parsley all winter, but the deer adore it

so I've never had it later than August. As a result, I've never

even bothered to plant it in the sunny half of the garden (where I put

the plants which will grow on warm winter days.) Nevertheless, my

small bed emerged from the snow a week or so ago green and

beautiful! The plants tend to have short stalks in the cold, but

the leaves are delicious --- perfect for adding a bit of freshness to

tuna or egg salad or soups.

I've

always read that you can eat parsley all winter, but the deer adore it

so I've never had it later than August. As a result, I've never

even bothered to plant it in the sunny half of the garden (where I put

the plants which will grow on warm winter days.) Nevertheless, my

small bed emerged from the snow a week or so ago green and

beautiful! The plants tend to have short stalks in the cold, but

the leaves are delicious --- perfect for adding a bit of freshness to

tuna or egg salad or soups.

Of course, no winter

garden is complete without scads of Egyptian

onions. I

planted a couple of beds of them, and then tried to compost the extras,

which meant I instead spread volunteer onions all over the yard.

You can never have too many, though --- I put the fresh green tops into

omelets and egg salad and cut up the entire onions into soups.

Meanwhile, inside, we

still have enough sweet potatoes and garlic for several months, though

the carrots are beginning to reach the bottom quarter of the drawer and

we've only got three butternut squash left. The freezer is still

full of the bounty of the summer, and the only vegetables we buy in the

store are potatoes and onions (because our crops were disappointing

this year.) And now it's February, and time to plant the first

lettuce bed!

If

you've been following along for a while, you may remember my series

about traditional

Chinese farming practices. The book Farmers

of Forty Centuries

opened my eyes to farming methods that were clear forerunners of modern

organic gardening, complete with nitrogen fixing plants and massive

infusions of compost. As the name suggests, farmers in China

maintained the fertility of the same garden patches for as long as

4,000 years using their ancient techniques.

If

you've been following along for a while, you may remember my series

about traditional

Chinese farming practices. The book Farmers

of Forty Centuries

opened my eyes to farming methods that were clear forerunners of modern

organic gardening, complete with nitrogen fixing plants and massive

infusions of compost. As the name suggests, farmers in China

maintained the fertility of the same garden patches for as long as

4,000 years using their ancient techniques.

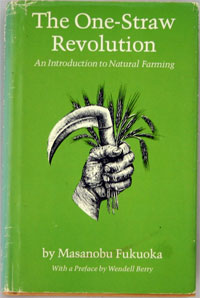

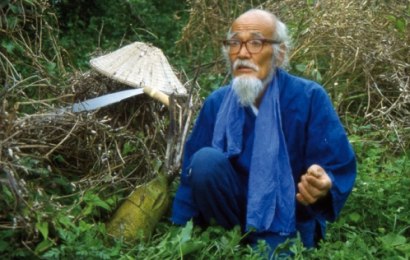

Fast forward ahead just

forty years after the book's publication date, and farming practices in

Japan (once very similar to those in China) turned around 180

degrees. After the end of World War II, Japanese farmers were

sucked in by the allure of time-saving American "innovations" like

chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides. According to

Masanobu Fukuoka, author of The

One-Straw Revolution, centuries of building

humus-rich soil washed away in just twenty years. Within one

generation, the Japanese soil was dependent on ever greater amounts of

chemical fertilizers to produce a crop.

Was there any way for

Japan to return to a more natural way of farming? Fukuoka said

yes, and his book struck a chord with both Japanese folks and Americans

in the 1970s. Stay tuned for his insights in this week's

lunchtime series.

| This post is part of our One-Straw Revolution lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Another winter day at Wetknee

where the snow is taking its sweet time saying goodbye.

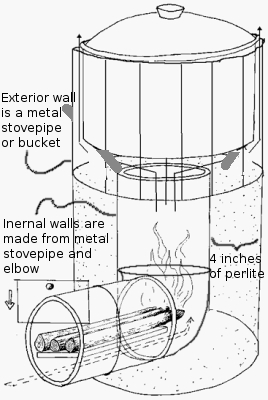

Rocket stoves are currently

being

introduced to several third world countries to help lower the pressure

of firewood harvesting on native forests. The stoves are designed

to need very little wood in order to heat up your

cook pot, so trees get left in place. I love the concept, but

can't help wondering --- why don't we promote rocket stoves in the U.S.

too? I'd never tell someone in a third world country to institute

environmentally friendly measures I wasn't willing to put into practice

in my own life.

Before I knew it, I'd penciled a rocket stove onto our ten year plan

and started researching. First, I discovered that you can't use

rocket stoves inside because they're basically an efficient

hearth. So, in practice, they'll probably be part

of a summer kitchen in our long term plan --- something I want anyway

because I always dread turning on the stove on a sweltering summer day.

The video I've embedded above is well worth watching if you'd like to

build your own rocket stove. It looks like we could probably make

one quite cheaply, though it would take quite a bit of trial and error

to figure out certain parts. The sheet metal looks an awful lot

like a stovepipe to me, suggesting that we might not need welding

skills (the part that scared us off building our own initially.)

Alternatively, we could buy one pre-made for around $125.

Have any of you built or used a rocket stove? What did you think

of it?

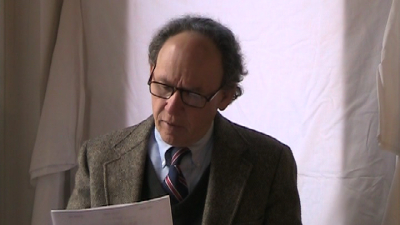

Masanobu

Fukuoka's The

One-Straw Revolution

is a hodepodge of advice for farming and living. To be completely

honest, I adored the first third of the book, but was annoyed by the

philosophical bent of the rest. Sure, I agree that we should

garden organically, eat locally, minimize our meat consumption, eat in

season, turn away from commercial farms and back to the small family

farm, reject growth economics, live simply, and work to live rather

than live to work. But those concepts are all old hat now.

Since I wasn't alive while he was writing the book, I don't really know

whether Fukuoka's ramblings were insightful and innovative at the time

or simply derivative.

Masanobu

Fukuoka's The

One-Straw Revolution

is a hodepodge of advice for farming and living. To be completely

honest, I adored the first third of the book, but was annoyed by the

philosophical bent of the rest. Sure, I agree that we should

garden organically, eat locally, minimize our meat consumption, eat in

season, turn away from commercial farms and back to the small family

farm, reject growth economics, live simply, and work to live rather

than live to work. But those concepts are all old hat now.

Since I wasn't alive while he was writing the book, I don't really know

whether Fukuoka's ramblings were insightful and innovative at the time

or simply derivative.

That said, the first

third of the book was rivetting. His farming

method (which I'll describe tomorrow) clearly paved the way for the

entire permaculture

movement. Fukuoka dubbed his technique "natural farming", and it

went far beyond simple organic gardening. He advocated working

with nature and mimicking natural processes, positing that many parts

of modern agriculture systems are only necessary because the farms are

out of balance and we're working against nature. As a result, he

also used the inspiring phrase "do-nothing farming", referring to the

aspects of modern agriculture that he did without.

Although there was still

a lot of work involved in Fukuoka's farm, his

do-nothing farming was unique. He promoted no-till techniques,

green manure, and mulching. You don't hear much about

Fukuoka nowadays, but I wonder whether he wasn't as influential in the

birth of the

permaculture movement as its self-styled father, Bill Mollison.

| This post is part of our One-Straw Revolution lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

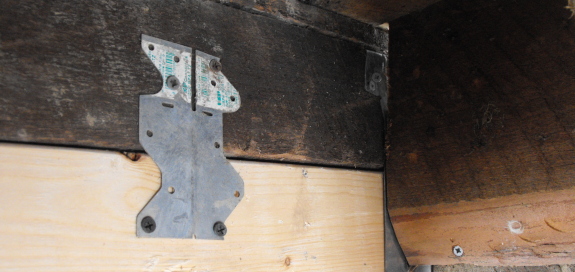

The home made storage

building is pretty much sealed up in the upper rafter section thanks to

several rounds of cutting salvaged wood to size and securing it in place.

While

I'm on the subject of more efficient stoves, I wanted to do some

research into efficient wood stoves for space heating. Our exterior wood stove

is a good choice for heat on our farm since wood is a renewable

resource (and is cheaper than most other options), but I'm still

concerned about the pollution that comes out the chimney.

Luckily, scientists have been plugging away at building a better wood

stove and have developed models that can eliminate 90% of the smoke and

use only about half the wood.

While

I'm on the subject of more efficient stoves, I wanted to do some

research into efficient wood stoves for space heating. Our exterior wood stove

is a good choice for heat on our farm since wood is a renewable

resource (and is cheaper than most other options), but I'm still

concerned about the pollution that comes out the chimney.

Luckily, scientists have been plugging away at building a better wood

stove and have developed models that can eliminate 90% of the smoke and

use only about half the wood.

The new,

energy-efficient stoves come in two categories. The first, shown

to the right, is a non-catalytic stove that increases its combustion

efficiency using firebox insulation, a large baffle that extends the

gas flow path, and pre-heated combustion air (which is actually a lot

like the reasoning behind the design of the rocket stove.)

Wood stoves with

catalytic converters (shown on the left) can cut emissions of even the

most efficient non-catalytic stove in half, but they don't seem to use

less wood. Although I'd love to be polluting less, catalytic wood

stoves aren't the best choice for most homesteaders. The $100 to

$200 catalytic converter wears out within two to six years, and you

need to be relatively adept at tinkering to keep it in prime operating

condition. The startup costs are also higher

So how much does a new,

energy-efficient wood stove cost? From what I can find online, it

seems like new non-catalytic wood

stoves start around $1,200 and go as expensive as you can

imagine. In 2009 and 2010, there's a 30% tax credit in effect for

buying wood stoves with at least 75% efficiency, which is a great deal

if you can use it. If you buy and burn a lot of wood, a more

efficient wood stove might pay for itself even without the tax credit

--- I estimate that we'd start saving money after about 4 years if we

bought the cheapest model.

Although efficient wood

stoves seem like a good idea, I'm still not ready to take the

plunge. I'm very curious about whether our current wood stove

could be retrofitted to increase its efficiency. Has anyone tried

that out?

So

what did Masanobu Fukuoka's natural farming technique look like?

In the fall, he seeded white clover, a winter grain (rye or barley),

and rice all at once into a field. The seeds were rolled in balls

of clay so that they could simply be dropped onto un-tilled soil rather

than being pushed beneath the surface.

So

what did Masanobu Fukuoka's natural farming technique look like?

In the fall, he seeded white clover, a winter grain (rye or barley),

and rice all at once into a field. The seeds were rolled in balls

of clay so that they could simply be dropped onto un-tilled soil rather

than being pushed beneath the surface.

That autumn, the clovers and

winter grains sprouted and grew while the

rice seeds waited. The clover formed a groundcover beneath the

rye or barley, crowding out weeds and fixing nitrogen to enrich the

soil. By spring, the winter grains were ready to be harvested ---

Fukuoka threshed

the grains

and tossed all of the straw back onto the fields, forming a thick

mulch. He added in a small amount of manure from his chickens,

but no other compost or fertilizer.

Meanwhile, the rice had

already sprouted and started to grow. The

young rice plants were trampled down when the winter grains were

harvested, but quickly sprang back to life, growing amid weeds and

clover.

Meanwhile, the rice had

already sprouted and started to grow. The

young rice plants were trampled down when the winter grains were

harvested, but quickly sprang back to life, growing amid weeds and

clover.

The traditional method

of growing rice in most of Japan and China

consisted of flooding the rice paddies for the entire growing season as

a method of weed control, but Fukuoka realized that rice is actually

healthier when growing in damp, but not sodden, soil. So he opted

to flood his fields for a mere week in the spring, long enough to drown

out most of the weeds and weaken the clover, giving the rice a head

start. Then he dried the fields back out and the rice grew

happily above its nitrogen-fixing groundcover. In the fall, he

harvested the rice and once again returned the straw to the field,

along with seeds for next year.

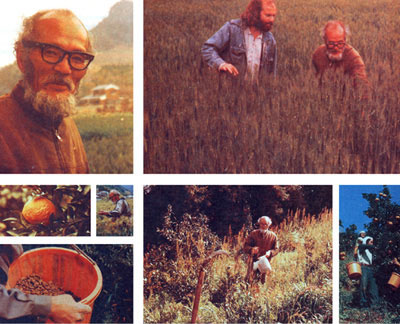

Fukuoka noted that after

20 years of using his natural farming method,

the soil on his farm was much richer than when he began. He

harvested just as much grain (or more) from his fields as the

commercial farmers using chemicals nearby. And the photos in his

book look remarkably weed-free --- I'm jealous.

| This post is part of our One-Straw Revolution lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We had a box of these corner

brackets that flattened out nicely with a few bangs of a hammer.

Extending the rafters will allow us to squeeze in some extra insulation.

My

mindset already seems to be taking in the permaculture

mantra "one man's trash is my

treasure."

My

mindset already seems to be taking in the permaculture

mantra "one man's trash is my

treasure."

All through our building

project, I've been letting the sawdust slip

into the mud and disappear, but this week I suddenly realized it was a

gold mine! I swept up about half a gallon and wish the

wood-cutting part of the project wasn't nearly over.

Shall I use my precious

sawdust for making bricks for a rocket stove or for mixing with wood

chips to

provide our mushroom spawn a better substrate? Choices, choices!

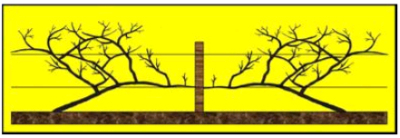

Masanobu

Fukuoka realized that his system of natural farming wouldn't be exactly

replicable in other parts of the world --- for example, we'd be

hard-pressed to grow rice here in Virginia. So he summed up his

method into four principles that can be used anywhere.

Masanobu

Fukuoka realized that his system of natural farming wouldn't be exactly

replicable in other parts of the world --- for example, we'd be

hard-pressed to grow rice here in Virginia. So he summed up his

method into four principles that can be used anywhere.

First, he admonishes us not to

till or turn the soil. Although Fukuoka

doesn't go into the science behind the

disadvantages of soil tilling,

he did mention that cultivating soil gives troublesome weeds like

crabgrass and dock a foothold. As my father can tell you, once

crabgrass gets into your garden, you might as well move on.

Principle 2 is "no

chemical fertilizer or prepared compost." I know the latter

may be fighting words! But I see his point ---

in nature, plant matter is naturally composted on the soil surface, a process

which promotes the growth of beneficial fungi.

Fukuoka adds fertility to his soil by returning straw (and a bit of

poultry manure) to the soil surface and keeping a groundcover of white

clover growing at all times.

Principle 2 is "no

chemical fertilizer or prepared compost." I know the latter

may be fighting words! But I see his point ---

in nature, plant matter is naturally composted on the soil surface, a process

which promotes the growth of beneficial fungi.

Fukuoka adds fertility to his soil by returning straw (and a bit of

poultry manure) to the soil surface and keeping a groundcover of white

clover growing at all times.

Third, Fukuoka refuses to

weed by tillage or herbicides.

Instead, he uses mulch, a clover groundcover, and temporary flooding

to keep the weeds in check. In addition, his winter grain/rice

rotation keeps the

fields constantly covered with crops, so weeds never have a fallow

period to gain a foothold.

Finally, principle 4 is "no

dependence on chemicals." All organic

gardeners will agree to that.

| This post is part of our One-Straw Revolution lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The home

made storage building got

about half way sealed today thanks to four tubes of caulk and five

tubes of liquid nails.

Human

names elude me. Without really trying, I can rattle off the

scientific names of hundreds of plants, tell you their lineage, their

uses, where they like to grow. But present me with a few people,

and they blur together into a sea of faces.

Human

names elude me. Without really trying, I can rattle off the

scientific names of hundreds of plants, tell you their lineage, their

uses, where they like to grow. But present me with a few people,

and they blur together into a sea of faces.

I can just hear what you

want to say --- "I have a hard time with names too." Let me

clarify with a short story. When I was a freshman in college, a

girl sat at my table every day, but for weeks (months? maybe even the

whole first semester?) I didn't know who she was and I mostly ignored

her. Then, one

day, she brought a potted heather plant to lunch with her. "Nice

plant," I said. "Yes, it's a heather, just like my name," she

replied. A light went off in my head --- this girl's name was

Heather, which was a plant, so I could remember her! Now, to use

modern parlance, we are BFFs.

I've been thoroughly

enjoying everyone's insightful comments, especially over the last few

weeks, but it bothers me that I have a hard time remembering which one

of you is the pig farmer and which one lives on the prairie. I

considered asking you all to rename yourselves after plants, but then I

came up with an even better solution! Anyone who wants can now

create an

account on Walden Effect. This will make it easier for you since

your comments will post immediately (rather than waiting for me to

check in and mark them as non-spam.) You'll also be able to

create your own user page, with links to your main webpages, maybe a

photo of yourself, and hopefully at least one reference to a plant or

animal to jog my memory.

I hope you'll give it a

try! Just click here and follow the directions to

make your account and user page. If you run into any problems,

just email me and I'll make them better.

You might also want to read about all of the

registered users on Walden Effect.

Don't want to

share? That's okay --- you can still post comments anonymously or

by typing in your name just the way you always could. Either way,

I look forward to learning more about you!

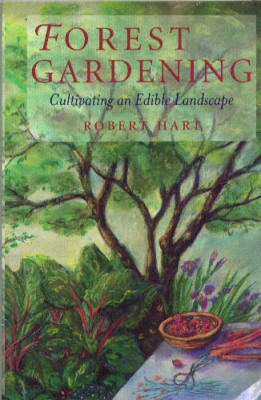

As

I mentioned before, Masanobu Fukuoka's natural farming helped inspire

the permaculture movement, but I ended up being drawn in a different

direction by his experiences. I've been struggling to develop a

workable no-till system for my garden over the last three years, and my

constant problem is lack of sufficient mulch. We mow

all of our grassy areas and add the clippings to our garden beds and even rake

leaves out of the woods

to top things off, but I still end up with bare soil and way too many

weeds. So you shouldn't be surprised that my epiphany upon

reading The

One-Straw Revolution had to do with mulch.

As

I mentioned before, Masanobu Fukuoka's natural farming helped inspire

the permaculture movement, but I ended up being drawn in a different

direction by his experiences. I've been struggling to develop a

workable no-till system for my garden over the last three years, and my

constant problem is lack of sufficient mulch. We mow

all of our grassy areas and add the clippings to our garden beds and even rake

leaves out of the woods

to top things off, but I still end up with bare soil and way too many

weeds. So you shouldn't be surprised that my epiphany upon

reading The

One-Straw Revolution had to do with mulch.

The organic gardening

and homesteading movement has us all growing our

own tomatoes and broccoli, but I'd say that 99% of us have never even

considered growing

our own grains.

And yet, grains make up a huge percentage of our diets. Clearly,

they also made up a huge percentage of Masanobu Fukuoka's garden.

Perhaps the solution to my mulch problem is to return to a more

holistic gardening method. If we grew all of our own grains as

well as all of our vegetables, I'd never be in need of mulch again.

Fukuoka says that his

method of growing grains uses one hour per week

per person, a figure that sounds remarkably manageable. Could we

tweak his system a bit, perhaps trading

buckwheat, sorghum, or corn for rice, and replicate his success?

I'm suddenly determined to find clover seeds, buy a bit of straw to

prime the pump, and plant my hull-less oats in a do-nothing test plot

rather than in a traditional garden bed.

| This post is part of our One-Straw Revolution lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Little

house in the suburbs dot com is hands down the coldest

automatic chicken waterer I've seen so far.

I can't prove it, but I feel

like all chickens can appreciate the simple comfort of a cool drink on

a hot summer day.

We've got side by side Avian Aqua Misers and one day last summer I put a

handfull of ice in one of them and noticed how our Plymouth Rock hens

favored the colder water.

I know it's not a scientific

test, but maybe I can expand the parameters next summer to see if

there's any truth to this crazy hypothesis?

Our homemade

storage building

continues to be a learning experience. When we started out, I

blithely said, "Let's put in as much insulation as possible despite the

cost," and Mark agreed. What I didn't realize is that you have to

plan for your insulation needs from the get-go.

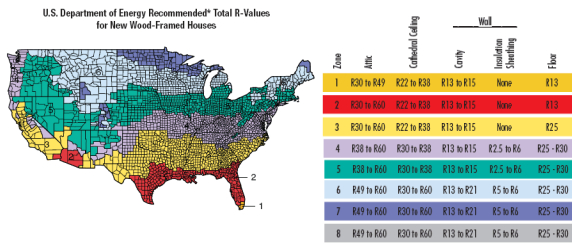

The map and chart at the

top of the page show EPA's insulation recommendations for new

wood-framed homes when heating with gas, heat pumps, or fuel oil.

(They recommend more insulation if you heat with electricity, and don't

even give you an option for heating with wood.) We're in their

zone 4, which means we should have at least R30 in our ceiling and R13

in our walls. The latter is easy, but the former is a bit of an

issue.

Assuming

you're using fiberglass insulation (which fits our wallet and

our remote setting), you need thicker wall or ceiling cavities to fit

more insulation. A typical 2X4 wall will hold up to R15 --- if

you try

to cram R19 in, you compress the insulation and, I believe, actually

get less insulative value than you would have with a lower rated batt

of insulation.

Assuming

you're using fiberglass insulation (which fits our wallet and

our remote setting), you need thicker wall or ceiling cavities to fit

more insulation. A typical 2X4 wall will hold up to R15 --- if

you try

to cram R19 in, you compress the insulation and, I believe, actually

get less insulative value than you would have with a lower rated batt

of insulation.

Our original rafters are 5.5 inches deep, which

would only allow us to put in R19 insulation up there --- makes me

chilly just thinking about it (although I think the trailer ceiling has

about R13.) So we extended our rafters with some two by fours,

giving us the space to increase our ceiling insulation to R30.

For future reference, here is the cavity depth you need for some common

insulation r-values:

- 3.5 inches --- R13

- 6 inches --- R19

- 9 inches --- R30

- 12 inches --- R38

Most of our building

project has been very forgiving of my learn-as-we-go mentality, but

insulation requires some forethought. For those who might want to

try their own hand at building --- shun the fault I fell in!

Plumjam.com has an interesting automatic

chicken waterer that caught my eye while I was enjoying their poultry

project pictures.

It's a huge improvement over

the regular gravity fed waterers, but still needs to be cleaned out,

and it cost more than an Avian Aqua Miser.

I'm not sure I would trust

the float not to get stuck, and would most likely be checking on it

often to see if it were flowing. I never have this concern with the

Avain Aqua Miser.

I would be willing to bet a

box of doughnuts that if the chickens were given a choice side by side

with this waterer and an Avian Aqua Miser they would forget all about

those two big scary holes to peek into and start geting all their hydration from

a source that will always provide clean drinkable water without nearly

as much fuss.

A

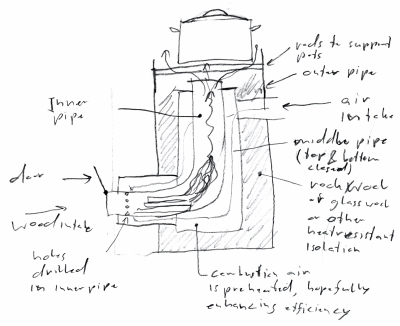

few of you were as intrigued by the rocket stove

concept as I was, and Roland's comments sent me searching the web for

more information. Basically, I wanted to know if I could design a

slightly modified rocket stove made out of found/bought materials to

simplify construction. I was also interested in any updates to

the design that might maximize efficiency.

A

few of you were as intrigued by the rocket stove

concept as I was, and Roland's comments sent me searching the web for

more information. Basically, I wanted to know if I could design a

slightly modified rocket stove made out of found/bought materials to

simplify construction. I was also interested in any updates to

the design that might maximize efficiency.

Preheating

the combustion air

The drawing shown here

is Roland's suggestion for preheating the combustion air to increase

efficiency, in much the way that efficient

space-heating wood stoves

work. A search of the web turns up contradictory pages --- folks

who have tried similar methods are split on whether it increases

efficiency or not. Many sites suggest that the conventional

design already preheats the combustion air by passing the air intake

underneath the burning fire, so I think I'll stick with that.

Insulation

Insulating the burning

chamber is another important factor in rocket

stove efficiency. The official Aprovecho design calls for making

your own fire bricks, which are rated at about R10 when fully

assembled. Roland's suggestion --- perlite --- has an R-value of

2.7 per inch, so four inches of loose-filled perlite placed between an

inner and an outer wall could be a much easier option than making our

own fire brick. (For future reference, other folks mention using

materials such as vermiculite (R2.08 per inch) and pumice (R2 per

inch).)

Body

materials

I've seen various DIY

rocket stove options using found or bought

materials, and the ones that caught my eye used nested stove

pipe. The image shown here is my revised version of the official

design made out of one big stove pipe, two pieces of smaller stovepipe,

and an elbow to connect the smaller stovepipe pieces together. As

Roland mentioned, the bigger stovepipe might be replaced by a metal

bucket --- otherwise, I'd have to add some kind of cap to keep the

perlite from coming out the bottom. I'm envisioning the pot

sitting on pieces of rebar stuck through the exterior walls rather than

welding anything together.

There's a bit of math

involved in deciding how high the interior

chamber should be and how much air space should be left between the pot

and the skirt -- more on that later!

What

do you do if you want to install an automatic chicken coop door but

you don't have electricity running to your coop?

What

do you do if you want to install an automatic chicken coop door but

you don't have electricity running to your coop?

Chicken

coop door.com has

recently come out with a new solar powered option that will save you

the chore of letting your girls out in the morning and remembering to

lock them back up at night.

The price is 324 dollars and maybe worth it if you don't have the skill and

time to build an automatic chicken coop door yourself.

Edited to add:

After years of research, Mark eventually settled on this automatic chicken door.

You can see

a summary of the best

chicken door alternatives and why he chose this version here.

If you're planning on

automating your coop, don't forget to pick up one of our chicken waterers. They never spill or

fill with poop, and if done right, can only need filling every few days

or weeks!

As

part of my continued obsession with lower-energy cooking, I

decided to try to make a haybox to cook my chicken carcass down into

stock Sunday. Someone (Heather?) had emailed me in response to my

Dutch

oven post,

telling me that you can bring a pot of incipient soup to a boil, wrap

it in towels, and leave it alone for the afternoon. The cast iron

and towels will hold in the heat, and the soup will cook itself.

As

part of my continued obsession with lower-energy cooking, I

decided to try to make a haybox to cook my chicken carcass down into

stock Sunday. Someone (Heather?) had emailed me in response to my

Dutch

oven post,

telling me that you can bring a pot of incipient soup to a boil, wrap

it in towels, and leave it alone for the afternoon. The cast iron

and towels will hold in the heat, and the soup will cook itself.

While researching rocket

stoves,

I stumbled across a mention of hayboxes, which seem to work on a very

similar principle to Heather's idea. You fill up a box with hay

(or other insulation), put in your boiling pot, and leave it alone for

several hours. I've seen figures suggesting that using a haybox

with long-cooking recipes like chicken stock will save 80% of the

energy you would use to simmer the stock on the stove. You should

leave the pot in the haybox somewhere between once and twice as long as

you would have left it on the stove. If you're worried about

bacteria, bring the whole thing back to a boil for a few minutes on the

stove before serving.

So how did my experiment

go? I brought my carcass and water to a boil and tucked it into

an old comforter in a cardboard box. (The image on the left shows

the pot before I bundled the rest of the comforter over the top.)

Our house temperature was low on Sunday --- 50 degrees Fahrenheit ---

but when I peeked in six hours later, the pot was still steaming and

the stock was a lovely yellow. Success!

Everett commented on my mention of

planting clover to

say:

I don't know why inoculant is so hard to spell, but I struggle with it too and seem to have to look it up every few weeks. Anyway, back to the point....

If you're not a gardener, you may not realize that nitrogen is usually the limiting ingredient in many plants' growth, and is thus one of the big three components of chemical fertilizers. Organic gardeners often add nitrogen to the soil with compost or manure, but others take advantage of nitrogen-fixing bacteria to turn the copious nitrogen in the atmosphere into nitrogen their plants can use. This week's lunchtime series will explore how this symbiosis can be worked to your advantage in the garden.

Check out our chick waterer, perfect for day-old

chickens!

| This post is part of our Nitrogen Fixing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

A perfect complement to

yesterday's solar

powered automatic chicken coop opener would be this portable hyrdogen

generator.

Kristie

Lu Stout has an interesting post about this exciting new product

that will allow everybody to generate their own hydrogen from water and

store it in a safe, low pressure battery-like container. No word yet on

how much it might cost, but plans are to have a tabletop model

available by the end of 2010.

Getting off the grid with

solar or wind has always come back to battery storage. If this

technology improves, it could replace most of those expensive and toxic

chemical batteries and bring alternative energy within the reach of the

common homesteader.

As

you've probably gathered by now, we don't live next to the road.

A third of a mile of floodplain lies between our trailer and our car

parking area, and during this abnormally wet winter that means a third

of a mile of mud.

As

you've probably gathered by now, we don't live next to the road.

A third of a mile of floodplain lies between our trailer and our car

parking area, and during this abnormally wet winter that means a third

of a mile of mud.

It's been weeks since the ground has been dry enough for the golf cart

to traverse our swamp, but we went ahead and bought a vanful of building

supplies last week to finish up the homemade

storage building.

Since insulation is, by definition, light and airy, we didn't have a

problem hauling in enough to finish the walls. But the sheets of

plywood we plan to cover the interior with were another matter.

Mark wisely asked at the store to have the four by eight panels cut in

half, but even a four by four sheet of plywood is extremely

ungainly. I set out on Monday to see how many sheets I could haul

through the mud to move our project along.

Attempt 1 began with me

hoisting four sheets onto my head. By the time I crossed the

creek, I knew this method wasn't going to work. Luckily, I ran

into the heavy

hauler

halfway home, lashed the plywood down, and marveled over how wheels

made the work lighter. Elapsed time: 1 hour. Sheets per

hour: 4.

My

major physical weakness is carpal tunnel, and I knew that I couldn't

pull the heavy hauler through the mud again without waking up the next

night with tingling hands. So for attempt 2, I got out my hiking

backpack and some rope. Out at the van, I lashed four sheets onto

the backpack and manhandled it onto my back. The boards felt

positively light, but they also went a bit akilter and I had to

constantly push them back into place. Elapsed time: 40

minutes. Sheets per hour: 6.

My

major physical weakness is carpal tunnel, and I knew that I couldn't

pull the heavy hauler through the mud again without waking up the next

night with tingling hands. So for attempt 2, I got out my hiking

backpack and some rope. Out at the van, I lashed four sheets onto

the backpack and manhandled it onto my back. The boards felt

positively light, but they also went a bit akilter and I had to

constantly push them back into place. Elapsed time: 40

minutes. Sheets per hour: 6.

For

attempt 3, I got smart and stupid all at once. First the smart

part. I realized that the pea trellis material

would make a perfect sling to hold the wood together, making it easy to

tie it onto my backpack. The whole thing seemed so easy, in fact,

that I got greedy and decided to haul in six sheets instead of

four. Bad idea! By the time I sloshed through the mud and

made it home, I was worn out! Elapsed time: 50 minutes.

Sheets per hour: 7 --- but that doesn't count the hour I spent

collapsed on the couch afterwards!

For

attempt 3, I got smart and stupid all at once. First the smart

part. I realized that the pea trellis material

would make a perfect sling to hold the wood together, making it easy to

tie it onto my backpack. The whole thing seemed so easy, in fact,

that I got greedy and decided to haul in six sheets instead of

four. Bad idea! By the time I sloshed through the mud and

made it home, I was worn out! Elapsed time: 50 minutes.

Sheets per hour: 7 --- but that doesn't count the hour I spent

collapsed on the couch afterwards!

At least we have some

wood to work with, now. Mark has plans to fix up the driveway,

which may make all of this muddy hauling a thing of the past.

More on that later....

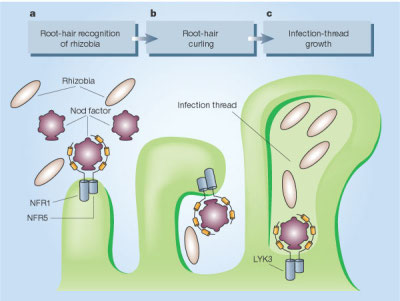

"Nitrogen,

nitrogen everywhere, but not a drop to drink," could be a plant's

plaintive song. The atmosphere we breathe is 78% nitrogen, but

plants are incapable of putting the elemental nitrogen to use.

Instead, they need ammonia or nitrate and depend on the useful nitrogen

they can suck out of dead plants and animals as part of the nitrogen

cycle.

"Nitrogen,

nitrogen everywhere, but not a drop to drink," could be a plant's

plaintive song. The atmosphere we breathe is 78% nitrogen, but

plants are incapable of putting the elemental nitrogen to use.

Instead, they need ammonia or nitrate and depend on the useful nitrogen

they can suck out of dead plants and animals as part of the nitrogen

cycle.

Nitrogen-fixing bacteria

are the flip side of the coin. These

microorganisms can take the nitrogen from the air and turn it into a

useful form, but the process takes up vast quantities of energy.

Some bacteria species are able to scavenge the energy on their own, but

others have opted to team up with nitrogen-hungry plants.

The best-known symbiosis

is between rhizobia bacteria and

legumes. It all begins when a bacterium senses flavonoids given

off by the legume's roots. "Home for sale!" the flavonoids say,

and the bacterium secretes a chemical in reply --- "I'd like to move

in." "Great!" says the root, and it curls its tiny root hair

around the bacterium to make a safely enclosed root nodule. The

plant fills the nodule with carbohydrates (free energy!), proteins, and

oxygen, and the bacterium responds by fixing atmospheric nitrogen into

ammonia to feed the plant. The pair lives happily ever after.

| This post is part of our Nitrogen Fixing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Mark

read my

post this morning and said, "Everyone's going to think that I'm a

slacker, sitting back and watching you carry all that plywood

in!" I said, "Of course not! Everyone knows you were

working really hard on another job and that you usually do all the

hauling anyhow." "Hmph," Mark replied.

Mark

read my

post this morning and said, "Everyone's going to think that I'm a

slacker, sitting back and watching you carry all that plywood

in!" I said, "Of course not! Everyone knows you were

working really hard on another job and that you usually do all the

hauling anyhow." "Hmph," Mark replied.

Clearly Mark was right,

since my mom just sent me this email: "Does Mark haul any plywood in??

I love the photos of you,--but, seriously, does he?? What has

Mark been doing while you've been dragging?"

I'm going to post more

about it tomorrow morning, but Mark was busy doing manly chores in

town, talking to mechanics who won't really talk to me and moving

forward on the driveway repair project. I took the photos of

myself using the timer function on the camera. Shame on you all

for not thinking that Mark does his share!

To further muddy the

waters, here's a picture of the golf cart in the snow a week ago....

We've had a really good test

for the storage

building roof today

thanks to a steady stream of rain. No leaks so far while we begin the

process of measuring, cutting, and installing the plywood that Anna

worked so hard to bring in yesterday.

Remember

our huge pile of

firewood? We

ran through it unbelievably fast --- first the power was

out for two weeks

and we had to keep a big fire going just to keep the trailer above

freezing due to lack of a fan. Then we had two weeks of below

freezing temperatures and again had to keep the fire raging to keep us

warm. The result is that the 1.75 cords of wood that we thought

would last all winter lasted a mere month.

Remember

our huge pile of

firewood? We

ran through it unbelievably fast --- first the power was

out for two weeks

and we had to keep a big fire going just to keep the trailer above

freezing due to lack of a fan. Then we had two weeks of below

freezing temperatures and again had to keep the fire raging to keep us

warm. The result is that the 1.75 cords of wood that we thought

would last all winter lasted a mere month.

So in January, we went

back to electric heat. I hated to give in to the coal-fired power

plant, but our firewood supplier took our $50 down payment and dropped

off the face of the earth. Due to major environmental guilt, I

keep the trailer between 40 and 50 degrees when heating with

electricity, which is really quite comfortable if you wear layers (and

are used to it.)

That's all a long

explanation for why Joey

came in his truck last week instead of his car --- he wanted to drop

off a load of firewood for his poor, freezing baby sister. The

firewood was much appreciated, but the truck got stuck due to

completely treadless tires. Rather than calling a tow truck to

haul Joey out, we called our mother and begged her to come pick Joey up

so that Mark and I could take advantage of this opportunity to haul

gravel for our driveway. (We ordered some of that from our hauler

too, but we really haven't heard from him in over a month....)

On Monday, Mark babied

the truck out of the mud (now thawed and thus a bit less precarious)

and took her to town to get new tires. We thought the two back

tires we needed to replace would come to about $300, but Mark came home

with a receipt for only $140 --- he had discovered the wonder of

retread tires! If you, like me, have never heard of retreads,

you're in for a treat. Old tires end up in a factory where

they're tested for safety and have the old tread buffed off, then a new

tread is is applied. The end result is nearly as good as a new

tire (and every bit as safe), for a fraction of the price.

Apparently, at this time, only big tires (R16 and greater) are

retreaded, so most of them end up going to large-scale trucking and

bussing fleets, but farmers are also retread fanatics. If you

have a truck that needs new wheels, retreads seem like the way to go!

Scientists

have discovered that inoculating legumes with nitrogen-fixing bacteria

can increase crop yields. The theory is simple --- if your plants

lack the proper bacteria to team up with, they're stuck begging ammonia

out of the soil rather than producing their own.

Scientists

have discovered that inoculating legumes with nitrogen-fixing bacteria

can increase crop yields. The theory is simple --- if your plants

lack the proper bacteria to team up with, they're stuck begging ammonia

out of the soil rather than producing their own.

But you can't just

inoculate your entire garden with one kind of

bacterium and be done with it. Most plants that team up with

nitrogen-fixing bacteria are picky about the bacteria species they move

in with. Clovers share one set of bacteria species, garden and

soup beans another, and alfalfa, soybeans, peanuts, clover, and peas

each have their own. You can often buy seeds already coated in

the proper inoculant, or can even transplant a bit of soil from your

previous pea patch to your new one to get the useful bacteria started.

As a side note, I was

intrigued to learn that legumes aren't the only

plants that team up with nitrogen-fixers. The other common,

nitrogen-fixing plant in our area is the shrub alder (Alnus

sp.) I've been keeping an eye out for some wild alders to

transplant into my forest

garden as a method

of naturally boosting the

area's fertility.

| This post is part of our Nitrogen Fixing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We forgot to use a level when

we were setting up the outer door frame of the storage

building and because of

that a small gap needed to be added towards the top to level it out.

Why

do gardeners start so many seedlings indoors when the plants nearly

always do just as well when planted in a cold frame or simply

direct-seeded after the last frost? My best guess is that the

same antsiness I feel as the days get longer affects everyone else

too. Starting some alpine

strawberries this

winter has been a good way to feed the ache without going nuts with

grow lights and flats.

Why

do gardeners start so many seedlings indoors when the plants nearly

always do just as well when planted in a cold frame or simply

direct-seeded after the last frost? My best guess is that the

same antsiness I feel as the days get longer affects everyone else

too. Starting some alpine

strawberries this

winter has been a good way to feed the ache without going nuts with

grow lights and flats.

It took two solid weeks

for my strawberries to germinate, but this weekend I noticed the first

tiny specks of white as roots started digging into the stump dirt.

Monday, the cotyledons began to unfurl from  the

seed coats, and Wednesday the flat was full of tiny green leaves, each

one heavy with a drop of dew. I guess it's nearly time to take

the lid off and let them start growing!

the

seed coats, and Wednesday the flat was full of tiny green leaves, each

one heavy with a drop of dew. I guess it's nearly time to take

the lid off and let them start growing!

We're due to start some

plants outside this week, too, if the ground thaws out. People

around here traditionally plant their first peas on Valentine's Day ---

it's a crap shoot, but in the years when the early peas grow, everyone

who bowed out is jealous. I'll also be tossing out some poppy

seeds, some for us to eat and some just for the bees.

So

let's return to Everett's comment --- should I buy an inoculant to get

my clover patch off to a good start? If you already have clover

growing in your yard (which we do), chances are good that the proper

bacteria are already present. Go out and dig up a plant, and you

should be able to see little white bumps on the roots --- the nodules.

So

let's return to Everett's comment --- should I buy an inoculant to get

my clover patch off to a good start? If you already have clover

growing in your yard (which we do), chances are good that the proper

bacteria are already present. Go out and dig up a plant, and you

should be able to see little white bumps on the roots --- the nodules.

However, even if the

nodules are present, your plants may not be

currently teamed up with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. The way to be

sure is to cut a nodule open and look at the color. Nodes that

are actively fixing nitrogen are pink or red inside, while inactive

nodes are white, tan, or green. My nodes were white --- why?

The clover I dug up was

right in the middle of our muddy mess, an area

which has been waterlogged for about a month due to heavy rains and

snows. When legumes are stressed, they stop feeding their

bacteria and start paying attention to their own survival, so acidic or

waterlogged soil, drought, lack of organic matter, or even high soil

temperatures can kill off your nitrogen-fixing bacteria. I'll dig

up another plant in the part of the yard where I want to plant my

clover (currently under snow), and if I find more white nodes, I'll

need to inoculate.

| This post is part of our Nitrogen Fixing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The do it

yourself storage building

now has a door up thanks to a couple more smashed brackets that work great at keeping the stopping

portion of the frame in place.

Somewhere in the middle

of the morning Thursday, the homemade

storage

building began to

feel like inside

rather than outside.

I could tell because Mark went outside, leaving the door ajar, and I

came along behind him and closed the door to keep the room warm.

And it was warm inside. Despite

being snowy and barely above freezing outside, once Mark fired up the

wood stove, the building heated up surprisingly fast. We don't

even have the insulation up in the ceiling yet, but within an hour we

were shedding our coats and working in our indoors clothes. I

guess we've been losing a lot

of heat from our exterior wood

stove to the outside!

I wonder if,

rather than saving up for an efficient

wood stove, we

should instead

make another small building and install two small wood stoves,

relegating the trailer to summer use. Not this year,

though! The garden is already starting to pull at my brain,

begging me to finish up winter chores and start the pruning.

(The photos above show

what I've been up to while Mark

was putting in the door --- covering the walls with a nice, smooth

plywood. I find myself getting lost in the swirls of the wood

grain.)

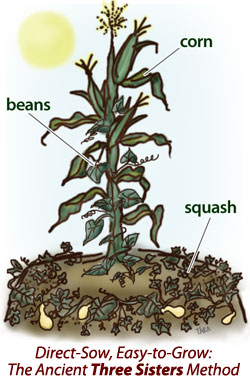

Due

to their nitrogen-fixing bacteria, legumes are a great way to break

your garden out of the nitrogen cycle. It's almost like printing

your own money, this ability to create your own usable nitrogen out of

thin air. So how do you put your newfound knowledge to use?

Due

to their nitrogen-fixing bacteria, legumes are a great way to break

your garden out of the nitrogen cycle. It's almost like printing

your own money, this ability to create your own usable nitrogen out of

thin air. So how do you put your newfound knowledge to use?

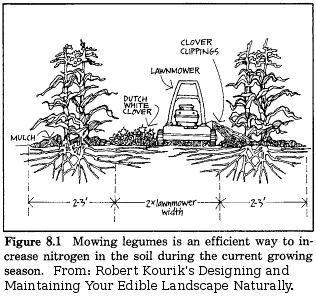

The first thing to

understand is that your legumes are holding onto

every bit of nitrogen they can. Planting beans beside corn plants

and hoping that the beans will feed the corn is mostly just wishful

thinking --- the beans are going to feed the beans. However, when

nitrogen-fixing plants die, the nitrogen in their bodies will end up

back in the soil, so the next crop will benefit. Take advantage

of this bit of biology by planting spring peas, then follow them with

summer corn.

Legumes also shake off

their nitrogen-fixing nodules when they are stressed by drought, shade,

defoliation, or grazing. Robert

Kourik

suggested planting a row of corn between rows of clover, mowing the

clover, and watching the corn take up the off-loaded nitrogen and

increase its  growth. In fact, for

those of you (like me) who are a bit leery of clover taking over in Fukuoka's

do-nothing clover/grain permaculture, you might get the best of

both worlds by interspersing rows of clover with rows of grain.

growth. In fact, for

those of you (like me) who are a bit leery of clover taking over in Fukuoka's

do-nothing clover/grain permaculture, you might get the best of

both worlds by interspersing rows of clover with rows of grain.

Of course, the most

common method of using legumes to increase a

garden's stores of nitrogen is green manuring. You plant a legume

as a cover crop, then till it into the soil when it is just about to

flower (the stage at which the plant contains the most nitrogen.)

This method, although widespread, is difficult in a no-till garden.

| This post is part of our Nitrogen Fixing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The downside to fabricating a

door

frame with a stopping

plate is allowing for enough room for your hand to grip the knob

without banging it against the frame when you pull it closed.

I decided to solve this

problem with a small section of a rubber door sweep. It blocks the gap

nicely while providing a smooth and soft surface for any close calls

that might happen.

With

Mark on the job, our second round of plywood hauling went much more

smoothly than the first. While I was finishing

up the inside walls of the homemade

storage building,

he wandered off to the barn and rigged a holder out of discarded boards

within half an hour. If I hadn't overloaded it ("Surely twelve

boards won't be too many to carry between us!"), it would have been

perfect, but as it was we barely made it two thirds of the way

home. Luckily, that's where dry ground begins, so Mark was able

to go get the golf cart and drive our load back to the building.

With

Mark on the job, our second round of plywood hauling went much more

smoothly than the first. While I was finishing

up the inside walls of the homemade

storage building,

he wandered off to the barn and rigged a holder out of discarded boards

within half an hour. If I hadn't overloaded it ("Surely twelve

boards won't be too many to carry between us!"), it would have been

perfect, but as it was we barely made it two thirds of the way

home. Luckily, that's where dry ground begins, so Mark was able

to go get the golf cart and drive our load back to the building.

Meanwhile,

I hauled in some more insulation using the old hoe trick. You

stick the handle of the hoe through the plastic wrapper of two rolls of

insulation, pushing one roll all the way back to the hoe blade so that

your head has room to sit between the two rolls. Stuff some

discarded underwear under your coat as a shoulder pad, and it's pretty

simple to carry the insulation home. Now we're all set to start

on the ceiling next week!

Meanwhile,

I hauled in some more insulation using the old hoe trick. You

stick the handle of the hoe through the plastic wrapper of two rolls of

insulation, pushing one roll all the way back to the hoe blade so that

your head has room to sit between the two rolls. Stuff some

discarded underwear under your coat as a shoulder pad, and it's pretty

simple to carry the insulation home. Now we're all set to start

on the ceiling next week!

"Is that men's underwear sticking out of your jacket pocket?" Mark

asked in disbelief as I set out.

It was a great day to take in

some southern Appalachian contemporary art and well worth a trip to the

big city on a Saturday. We got drawn to the William King museum to see

some big names like Matisse and Picasso, but I think the local

collection had more style and flavor. It was curated by Ray Kass, a

painter and writer who bi locates between Blacksburg and Manhattan.

Are you looking for some more blogs to

follow? I read over fifty, ranging from personal odysseys to

nonprofit newsletters, but only a few are so rivetting I want to share

them. These top three blogs are my personal picks based on:

posting frequently enough to keep me hooked, mixing personal and

informational in a fun proportion, and either being beautiful or well

written (or both.)

Are you looking for some more blogs to

follow? I read over fifty, ranging from personal odysseys to

nonprofit newsletters, but only a few are so rivetting I want to share

them. These top three blogs are my personal picks based on:

posting frequently enough to keep me hooked, mixing personal and

informational in a fun proportion, and either being beautiful or well

written (or both.)

Causabon's Book is probably the blog I

discuss the most at the dinner table. Sharon Astyk is a Jewish

homesteader and peak oil writer who sucks you in with her tales of

family life and simple living but adds plenty of meat about how to

store your food and prepare for the end of civilization. Her

posts are thought provoking and mirror my own world while also veering

off in other directions. (She used to write over on her personal blog, but is mostly writing at

the link above.)

Sugar Mountain Farm is "stories from a small

farm in Vermont's mountains raising pigs, sheep, chickens, ducks, dogs

and kids naturally on pasture." I started reading because we're

contemplating running pigs on pasture some day, but I kept reading

because Walter's photos were astounding --- really the best I've seen

on any blog. It's also fun to read about someone running a

successful small farm.

Not Exactly Rocket Science is a new favorite,

interpreting new scientific discoveries into layman's terms. This

isn't precisely homesteading, but you need to know the science to make

it all work!

What are your top three

blogs and why?

The home

made door frame stopping

plate gets most of its firmness from this bottom corner bracket. I

chisled out about a 1/4 of an inch of the floor to compensate for the

depth of the bracket. This is done to avoid a bulge in the future

linolem floor.

Last

year at this time, the snowdrops were blooming, but this year the

ground is hard and chilled. So I set out on Sunday afternoon to

search for spring.

For the first time in

weeks, the bees

were out on cleansing flights

and the nearby wild hazel bushes were close to blooming. The

catkins had elongated and softened, but still no sign of stamens ---

not spring yet!

In the forest

garden,

the comfrey leaves had died back into a brown mulch. But in the

center of each plant, little green tufts of new leaves were poking

up. Spring?

Down at the baby creek,

I got captivated by flashing ripples over the clay streambed. Not

spring, but definitely pretty.

Then, at last, I found a

flower. Sure, it's witch-hazel (which can bloom at intervals all

winter), but I'm counting it! February's first flower --- spring!

Did

you know that before the Industrial Revolution, the average person

worked for about two or three hours a day? Studies from a wide

range of pre-industrial civilizations show similar data --- it takes

only about fifteen hours a week to provide for all of our basic human

needs. And that's using hand tools.

Did

you know that before the Industrial Revolution, the average person

worked for about two or three hours a day? Studies from a wide

range of pre-industrial civilizations show similar data --- it takes

only about fifteen hours a week to provide for all of our basic human

needs. And that's using hand tools.

So why is the average

American working a dreary forty hours a

week? I've heard from at least half a dozen readers who say that

they'd love to live like Mark and I do, but only once they save up some

large sum of money or bring their microbusiness up to a level where it

can pay them some other large sum of money per year. So, even

though it's a bit off topic, I want to spend this week's lunchtime

series talking about money --- how much do we really need and how can

we make it without selling our souls?

Most of the information

I'll present is drawn from Joe Dominguez and Vicki Robin's Your

Money or Your Life

and the loosely affiliated Financial

Integrity website.

You can find the same nine step program, complete with worksheets and

examples, in both the book and the website. (Download

the worksheets and examples from the website for free here.)

Both are highly recommended! I'm going to gloss over some aspects

of the program that seem old hat to me, so if you like what you read

here and want to learn more, I highly recommend you go straight to the

source.

| This post is part of our Your Money or Your Life lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The hinge area of the home

made door frame ended up with a small gap even though I chisled out

enough wood for the hinge to be flush with the frame.

A medium sized strip of

stick-on foam was enough to seal most of the space.

Making a door frame from

scratch wasn't as hard as I thought it might be, but I can already see

how much time a fabricated frame would save, especially if you're trying

to make it look perfect.

My first attempt at

home mushroom cultivation involved morels. It was a dismal

failure, although I'd like to try again this year with all of the new

tricks I learned during my oyster

mushroom propagation semi-success. Meanwhile, Mark

talked me into adding a few morel plugs to this

year's spawn order.

The spawn arrived this weekend, and I quickly set out to plant the

morels.

My first attempt at

home mushroom cultivation involved morels. It was a dismal

failure, although I'd like to try again this year with all of the new

tricks I learned during my oyster

mushroom propagation semi-success. Meanwhile, Mark

talked me into adding a few morel plugs to this

year's spawn order.

The spawn arrived this weekend, and I quickly set out to plant the

morels.

The factsheet that came

with our order made planting morels from plugs seem extremely

easy. First, find trees that morels like (apples, ash, aspen,

elms, maples, or birch.) Make sure the soil under the trees is

appropriate --- no long-undisturbed soil like you'd find in a mature

forest, but plenty of organic matter and good drainage. We have

six young apple trees and six morel plugs, so it was easy to decide

where to plant them.

Next,

push the plugs all the way into the ground with your fingers at the

tree's drip line. Five minutes later, I was done planting.

It's really that simple!

Next,

push the plugs all the way into the ground with your fingers at the

tree's drip line. Five minutes later, I was done planting.

It's really that simple!

Now, the trick will be

getting them to fruit. Field and Forest Products asserts that

it's quite easy to grow morels in the soil (as long as you put them

near an appropriate tree.) The difficult part is getting them to

fruit. No one's quite sure how to do it, so your best bet is to

plant morels in several different areas to hedge your bets, then wait

and hope. For $7.50, I'm willing to gamble.

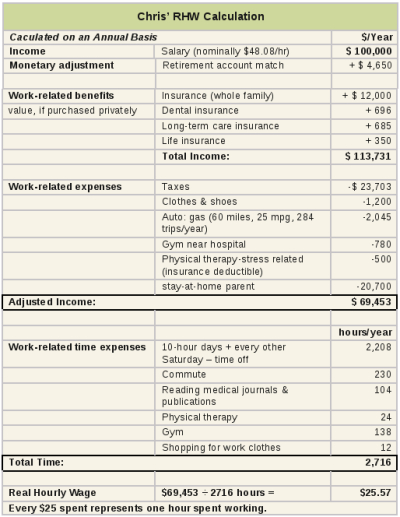

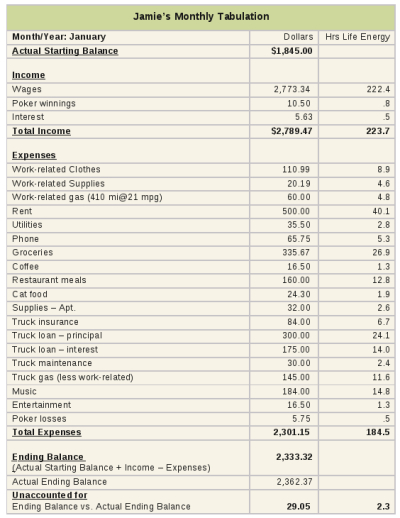

Did you know that your job

may be costing you money? Step 2 of Your

Money or Your Life

involves calculating your real hourly wage, which is a very powerful

exercise for folks who thought the $50 per hour they're supposedly

making really ends up in their pockets.

Did you know that your job

may be costing you money? Step 2 of Your

Money or Your Life

involves calculating your real hourly wage, which is a very powerful

exercise for folks who thought the $50 per hour they're supposedly

making really ends up in their pockets.

To follow along at home,

first make some notes on how long you really spend

working. Start with those 40 hours in your cubicle, of course,

but then add in the hour you spend grooming, your daily commute, and

the extra hour you vegetate in front of the tube to wind down after

work. Do you have to study or take classes to stay up to date in

your field? Do you end up spending a week in bed because you're

so run down from work that you catch the flu? Add it all up!

Next, add up all of your

work-related expenses. These include the

gas and upkeep on your car, those fancy duds you wear to the office,

every meal or $5 cup of coffee you consume away from home because

you're too busy to pack a lunch, the six pack of beer you drink while

winding down in front of the tube, the massages you pay for to wipe out

the work stress, and the money you give other people to do your

household chores since you don't have time (daycare, house cleaning,

lawn upkeep, etc.) Don't forget to include your taxes.

Finally, use the formula

below to figure our your real hourly wage.

Total hours you really work in a week

The example at the top

of the post from the Financial

Integrity website

shows how someone who thought she was making $48 per hour was

really making $25.57. The book includes someone who thought he

was making $11 per hour who was actually making $4. Without too

much of a stretch of the imagination, I can see how working could send

some job slaves into debt!

Luckily, I've very

rarely had a real job, but when I did I could

clearly see that the extra job-related time and money was a trap.

If you're working a real job, I encourage you to add it all up and

figure out your true hourly wage. Would you have accepted that

job if you'd realized you were only making $7 per hour?

| This post is part of our Your Money or Your Life lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I

would like to express some appreciation here for all the comments

lately, especially the tips given for the home

made door frame.

I

would like to express some appreciation here for all the comments

lately, especially the tips given for the home

made door frame.

I thought adding another stop

plate to the hinge side was a great idea and jumped on it today while

at the same time deleting the L bracket, which is no longer needed

since the liquid nails has finished curing.

Would I build another door

frame from scratch in the future? Yeah...it wasn't all that bad and the

finished product will meet our needs for years to come.

The

couple that works together, stays together...or pitches a huge hissy

fit and gets a divorce. Mark and I don't celebrate Valentine's

Day, but we do spend every day living in each others' pockets, usually

very amicably. In fact, one of my favorite parts of the day is

the time I spend working on a project with Mark.

The

couple that works together, stays together...or pitches a huge hissy

fit and gets a divorce. Mark and I don't celebrate Valentine's

Day, but we do spend every day living in each others' pockets, usually

very amicably. In fact, one of my favorite parts of the day is

the time I spend working on a project with Mark.

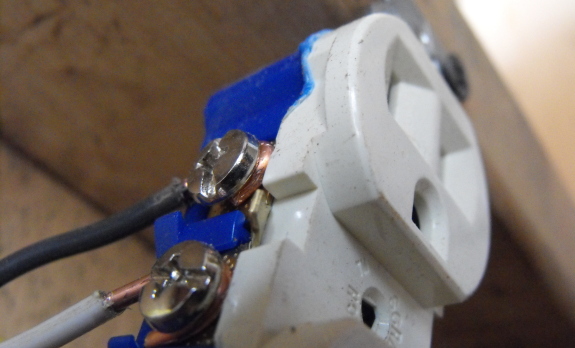

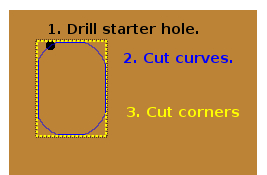

Even though I grew up

with a handy father, I somehow missed most of the lessons on basic

tool-use. So Mark has taught me how to use a power drill, a miter

saw, and so forth. Monday, I was putting up the last bit of wall

paneling, this time around the newly re-wired electric outlets.

How, I wondered, does one cut a small rectangle out of a piece of

plywood with a jig saw?

I know this is old hat

to those of you who dabble (or work) in construction, but I found this

technique elegant and captivating. First, Mark used a drill to

start a hole in the plywood. Then he cut along the line, curving

around each corner so that he could keep cutting until an oval section

fell out. Third, he went back and cut the corners out --- the

pictures hopefully make this process clearer than my description.

It's always a good day when I learn something new!

The

next step in the Financial Integrity process is to keep track of all of

your expenditures for a month. Now sum up the expenditures in

categories and divide each one by your real hourly wage.

The

next step in the Financial Integrity process is to keep track of all of

your expenditures for a month. Now sum up the expenditures in

categories and divide each one by your real hourly wage.

This can

be a bit of an eye-opening experience for many people because money is

an abstract for most of us. We often don't realize that the $500

plasma screen TV we bought on a whim last month actually represented 45

hours of work --- that's a solid week of full time employment!

This exercise alone is probably enough to tempt many people to cut back

drasticly on their spending.

On the other hand, dyed

in the wool skinflints like me sometimes come

to another realization. I simply don't believe in spending money

on non-essentials (something Mark has worked hard to train me out of),

and this step helped me realize that a few luxuries really are

worth it. I defnitely don't mind working for an hour to get to

enjoy a meal with my family at a restaurant now and then, or to get a

whole month of entertainment through netflix. After reading Your

Money or Your Life,

I finally made peace with spending a bit of money on luxuries.

Whichever end of the

spendthrift/skinflint spectrum you stand on, this

step is definitely worth your while. Try it out and watch your

spending habits change.

| This post is part of our Your Money or Your Life lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Holding up the plywood for the ceiling is a challenge to say the least.

I eventually adopted a

technique of using the upper portion of my arm along with the top of my

head to hold each piece in place.

I knew having a hard head

would come in handy one of these days and that day was today.

Hey you

two...what's your secret to a smooth working team?

George

W-Texas

Thanks for the question

George. It's really hard to pin down just one thing that makes two

people work well together. We try to figure out which task is best

suited for our skill set. For example. Anna is really good with math,

so she is in charge of measuring for this

project. I've got a

little more upper body strength so I usually do most of the heavy

lifting.

Last but not least you should

both agree on a time to stop working. A sure way to create extra

friction is to have one person thinking it's 10 minutes till the end of

the day and the other wanting to push through till sunset. Anna and I

usually wind down around 4pm and shift into an evening chore routine.

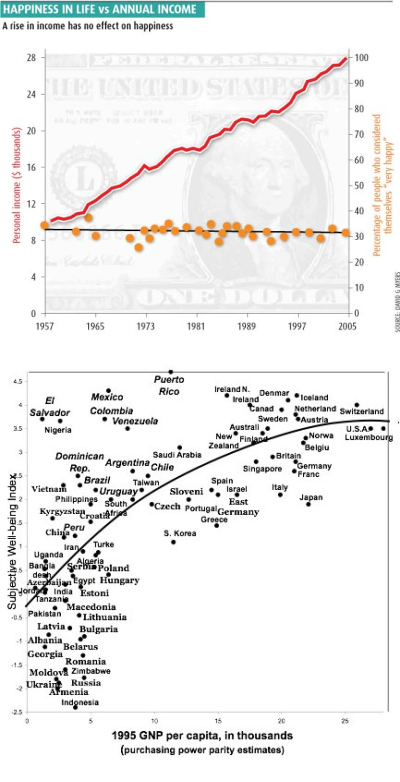

Many

people chase the almighty dollar because they think having more

money will make them happy. But scads of scientific studies have

shown that people with more money are no happier than those with less

(once you pass over the lowest income hurdle of having food and

shelter, that is.)

Many

people chase the almighty dollar because they think having more

money will make them happy. But scads of scientific studies have

shown that people with more money are no happier than those with less

(once you pass over the lowest income hurdle of having food and

shelter, that is.)

In fact, affluence is a relative thing --- if

you hang out with folks who barely have two pennies to rub together and

you've got two nickels, you're going to feel rich. On the other

hand, if you hang out with someone who owns his own island, you're

going to feel poor despite having a huge house and a fancy car and your

own yacht.

The American dream tells

us that we'll really be happy once we've got

all of the modern conveniences that our neighbors have, but most of the

time

when you try to have it all, you just end up with lots of little bits

of nothing. You work so many hours that you barely enjoy your

McMansion, then you're putting in overtime to save for your

kids' college education and end up feeling like you're living with

strangers. How can you break out of the cycle of measuring

yourself against your neighbors and always wanting more?

The trick is to learn

the value of "enough" by recalibrating your financial sensors.

Throw away your

television and stop listening to commercial radio --- those ads that

you think you can ignore are really seeping into your dreams.

Even movies are nefarious --- have you noticed that most movie

characters have a fancy new car and all of the modern

conveniences? By watching, you're telling your psyche that these

movie stars are who you want to measure yourself by.

If you can disentangle

yourself from the mainstream media, chances are you'll stop wanting so

much stuff. Mark and I are barely middle class by most people's

standards, but when people ask me what I want that I don't have, I

honestly can't think of anything. (Except more mulch, of

course...) By learning that "enough" for us costs very little

money, we were able to quit our

jobs and devote most

of our time to the things we really enjoy.

I think that people who

achieve financial independence and

true happiness are marked by only one thing --- they can figure out

when they have enough. Are you always in search of the next

raise, a new car, or a fancy gadget to make you happy? Or do you

realize that the things you really value in life are time with friends

and family, time to explore your hobbies, and time to change the

world? If the latter, then you have learned the value of enough

and can skip most of the Financial Integrity process --- you're there!

| This post is part of our Your Money or Your Life lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We decided to go with these

peel off and stick linoleum pieces for the floor of the home

made storage building.

They turned out to be a cheaper option compared to getting a roll of

the stuff and I'm thinking a bit easier for amateurs like us. It was a

smooth operation and we had most of it done before we knew what hit us.

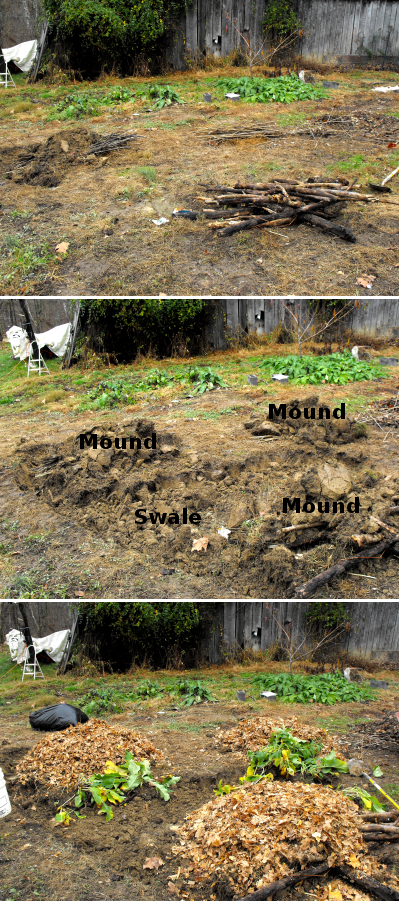

Last fall, I

raked leaves out of the woods to cover nearly all of my vegetable

garden beds.

My hope was that the leaves would keep weeds from growing over the

winter, expedite spring planting, and also rot down to fertilize the

soil.

Those leaves seem to

have done their weed-killing job admirably. The photo above is a

bed which didn't end up getting mulched --- it's now completely covered

with dead-nettles and chickweed. The bed below was mulched ---

notice the bare soil where I raked the leaves back to give me a spot to

plant poppies. The soil under the leaves was also unfrozen and I

glimpsed a spider scurrying around, which is in stark contrast to the

lifeless permafrost atop the un-mulched bed.

I was a bit disappointed

to see that the leaves hadn't decomposed much at all, but in a way

that's a good thing. We'll add manure before planting to boost

the fertility of the soil, and will push leaves back around plants once

they come up to keep the weeds at bay. I can already feel the