archives for 12/2009

Mark and the farm are

training me to be more flexible, to resist my urge to set up trips

weeks in advance. Monday, I took a look at the weather forecast

and saw chilly rain all week with nights above freezing. Cold

rain is the absolute worst weather for working outside, and with the

warmish nights from the cloud cover we won't have to worry about our chickens' waterers

freezing. Time to head up to Ohio to visit with Marks' family!

I have to admit that my

new-found flexibility was due in part to not wanting to do our laundry

outside in the rain. I'm usually pretty hardcore, but now and

then I wimp out and look forward to using a real, live washing machine.

Warm water, here we come!

The USDA National

Agroforestry Center

is experimenting with ways to combine trees and pastures.

Livestock (primarily cows) are grazed between widely spaced pine trees

that are grown for timber. The cows don't eat the trees, but they

do benefit from the shade and wind shelter. If I was a large

scale farmer rather than a homesteader, I would find this idea

enticing, but I'm really looking for a system in which the plants and

animals are more intertwined.

The USDA National

Agroforestry Center

is experimenting with ways to combine trees and pastures.

Livestock (primarily cows) are grazed between widely spaced pine trees

that are grown for timber. The cows don't eat the trees, but they

do benefit from the shade and wind shelter. If I was a large

scale farmer rather than a homesteader, I would find this idea

enticing, but I'm really looking for a system in which the plants and

animals are more intertwined.

While looking into the

history of forest gardening, I stumbled upon Forest

Farming,

by J. Sholto Douglas and Robert A. de J. Hart. The book isn't a

riveting work of art and it spans too many climate zones to be a

useful how to book, but I was inspired by the presence of livestock in

the forest farm systems. Douglas and Hart suggest planting

pastures of trees that drop edible fruits and nuts to feed the

livestock. The multi-layered nature of the forest allows for

higher productivity than a single layer pasture can produce, and the

livestock add fertility back to the system with their manure.

| This post is part of our Forest Pasturing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I learned a while back that a good set of knee

pads can make a big difference at the end of a day when you need to be

close to the ground. What I never got used to was how they tended to

cut off the circulation. My new favorite knee protector is this red

foam rubber pad. It provides a bit more wiggle room and doubles as a

place to sit when you need to take a break.

I learned a while back that a good set of knee

pads can make a big difference at the end of a day when you need to be

close to the ground. What I never got used to was how they tended to

cut off the circulation. My new favorite knee protector is this red

foam rubber pad. It provides a bit more wiggle room and doubles as a

place to sit when you need to take a break.

A couple of weeks after my

big kill, we've had time to try out a few venison recipes.

I've learned a lot, and find myself enamored of the taste, which seems

closer to high quality beef than anything else.

A couple of weeks after my

big kill, we've had time to try out a few venison recipes.

I've learned a lot, and find myself enamored of the taste, which seems

closer to high quality beef than anything else.

Our first and best

experiment was grilling

the tenderloin (on either side of the backbone) and upper ham (the top

of the "thigh" of the back legs). We let the meat marinate in oil

first since venison tends to be very lean, then rubbed it with some

salt and pepper before tossing it on the grill. That was so

delicious, we all ended up in rapture. Hard to beat.

For my second attempt, I

wanted to try some of the stew quality meat --- the front legs, the

lower parts of the ham, and other random spots around the deer. I

tried roasting the

venison up with some root vegetables, but I was disappointed ---

the taste was good, but I hadn't taken out all of the white stuff

(tendons?) that is so ubiquitous in the lower quality cuts of the

deer. The white stuff cooks up to be very chewy and hard to

eat. I considered this a failure, though Mark gamely munched his

way through and proclaimed it a success.

My third attempt went

much better. Again, I used some of the stew quality meat, but

this time I threw it in the food processor first to be chopped to

little bits. The white stuff stayed unchopped and was easy to

pull out, then I mixed up potsticker

filling with the remaining meat. Those were some of the best

potstickers we've ever eaten! More rapture.

For my next experiment

with the stew meat, I want to try to make Italian sausage. Stay

tuned....

Although

pigs haven't really been the focus of our livestock fantasies in the

past, everything I read about forest farming pushes me toward

swine. Unlike goats and sheep, pigs aren't woody plant

eaters. In fact, once a tree exceeds two feet in height, they

tend to leave it alone. Although they are prone to root up the

soil, if pigs are rotated through several small pastures, they do

minimal damage.

Although

pigs haven't really been the focus of our livestock fantasies in the

past, everything I read about forest farming pushes me toward

swine. Unlike goats and sheep, pigs aren't woody plant

eaters. In fact, once a tree exceeds two feet in height, they

tend to leave it alone. Although they are prone to root up the

soil, if pigs are rotated through several small pastures, they do

minimal damage.

Mulberries were the

biggest factor that pointed me toward pigs. In Tree

Crops,

J. Russell Smith notes that an everbearing mulberry tree can provide

all of the food a pig needs for three solid months (from July through

September.) I would add in a chestnut tree and a persimmon tree

(to bear in the fall) and a honey locust tree (to bear in the early

winter), then count on my pigs getting a lot of their nutrition from

fresh green undergrowth in spring and early summer. It sounds

like I might be able to devise a system where I wouldn't need to feed

my pigs supplemental grain except in late winter.

Traditionally, farmers

around here used to turn their pigs loose in the

woods in the fall to fatten on fallen acorns, so oaks would be an

obvious addition to the pig forest pasture. However, I don't

think we'll include oaks in our plans since they tend to fruit heavily

only once every few years, which leaves gaps in our production cycle.

| This post is part of our Forest Pasturing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

In the 4th generation of our home

made chicken tractors I decided to add a day time roost in addition

to the night time area. I don't have any proof, but I think it's good

for the morale of the flock to have multiple areas where a hen can be to

herself and get some personal space.

In the 4th generation of our home

made chicken tractors I decided to add a day time roost in addition

to the night time area. I don't have any proof, but I think it's good

for the morale of the flock to have multiple areas where a hen can be to

herself and get some personal space.

Time for another daffodil

giveaway! I said it

best last year:

Time for another daffodil

giveaway! I said it

best last year:

Daffodils are a fact of life here at Wetknee Farm, one of the few remants of the previous owner who left decades before we arrived. When we first came to the farm, we discovered that daffodils had spread out from the old homeplace to cover nearly an acre of good garden ground. I gave away hundreds, sold hundreds, and ended up transplanted another thousand or so out of the way. Now the garden is once again encroaching on my daffodil patch --- time for a daffodil giveaway!

I don't know quite how many daffodil bulbs we'll be giving away. We've

got a couple of hundred at the moment, but we're also giving them away

with our Avian Aqua Miser

orders. So, whatever's left come January 1 will go to our lucky

winner.

To enter the

giveaway, just leave a comment on any post by December 31. I'll

throw your name in the hat (multiple times if you make multiple

comments)

then will contact the winner through the blog. (Be sure

to check back on January 1 to see if you won!) That way you

have an incentive to leave us lots of comments. I look

forward to hearing from you!

Sheep

and goats are a bit more difficult to grow in a forest pasture

situation since they like to eat twigs and thin-barked trees.

There is also less data available for good ways to combine these

livestock with trees, but I've got a couple of thoughts.

Sheep

and goats are a bit more difficult to grow in a forest pasture

situation since they like to eat twigs and thin-barked trees.

There is also less data available for good ways to combine these

livestock with trees, but I've got a couple of thoughts.

First, I suspect that

sheep and goats would work very well in the power

line cut if I planted it with trees that don't mind being coppiced

(willows, alders, hazels, and elders.) By rotating the sheep and

goats through small pastures, we could give the shrubs time to grow

back rather than being decimated by gnawing teeth.

We might also get away

with grazing sheep along with pigs amid large,

widely spaced trees. Unlike goats, sheep can live entirely on

pasture and they might eat up the woodier plants on the forest floor

that pigs would ignore.

| This post is part of our Forest Pasturing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The palomino grain cow

hide work gloves are still my preferred glove for handling heavy

jobs. I estimate that the work load here at Wetknee seems to chew

through them somewhere between 9 and 12 months, which is a good value when you consider the wear and tear you're saving on each

hand.

The palomino grain cow

hide work gloves are still my preferred glove for handling heavy

jobs. I estimate that the work load here at Wetknee seems to chew

through them somewhere between 9 and 12 months, which is a good value when you consider the wear and tear you're saving on each

hand.

I keep getting questions from folks wanting to

know the difference between Egyptian onions, potato onions, shallots,

and multiplier onions. All are perennial onions that reproduce by

bulbs, and it's easy to confuse them.

I keep getting questions from folks wanting to

know the difference between Egyptian onions, potato onions, shallots,

and multiplier onions. All are perennial onions that reproduce by

bulbs, and it's easy to confuse them.

Egyptian onions (also known as walking onions) are easy to

distinguish because they reproduce by little bulbs at the top of leaf

stalks. They don't make big bulbs, so are best eaten as green

onions or scallions.

"Multiplier onion" is a term used to refer to any onion that reproduces

by dividing its underground bulbs (just like garlic does.)

Multiplier onions can be separated into two categories --- shallots

(which form bulbs up to 1.5 inches in diameter) and potato onions

(which form bulbs up to 3 inches in diameter.)

We're growing potato

onions for the first time this fall, and I have to say that I've

already decided I love them.

I carefully planted them in raised beds a month ago and mulched them

heavily with leaves. Then, just as everything else in the garden

and

woods was turning brown and dying, the potato onions shot up fresh,

green sprouts.

Hooray for perennial onions!

All

this talk of rotational grazing makes Mark cringe because he knows it

means lots of fences. Is there a way to delete the fences and

instead add in more multi-purpose trees?

All

this talk of rotational grazing makes Mark cringe because he knows it

means lots of fences. Is there a way to delete the fences and

instead add in more multi-purpose trees?

When I was in Great

Britain, I loved their tradition of using hedgerows to

separate fields. The hedgerows consisted of closely planted trees

and shrubs, many of which produced fruits or nuts that could feed

livestock (or humans.)

Since our livestock

dreams are a few years in the future, we have time

to plant some hedges now in preparation. So far, the most

interesting edible hedge species I've read about include crab apples,

wild plums, Nanking cherry, trifoliate orange, blackberry, elder,

hazel, and rose. The goal is to plant them close enough together

that they create an impenetrable thicket and keep animals from breaking

through, but not so thickly that they drown each other out. I've

got a lot more reading to do on hedges, though, before I put anything

in the ground!

| This post is part of our Forest Pasturing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

These are a few pictures from our peaceful trip up north where winter

feels just a couple of weeks stronger.

We had a very fruitful visit to Ohio, both

literally and figuratively. I had my eyes peeled for useful seeds

and was thrilled to stumble upon a patch of honey locust and

osage-orange growing together in a floodplain. It was easy to

gather up two big bags of osage-orange

fruits to turn into a hedge, but I had to do some serious foraging

to find un-gnawed honey locust pods. I take this as a very good

sign --- if the wild animals are so fond of honey locust seeds,

hopefully our

idea of feeding honey locusts to pigs will pan out.

We had a very fruitful visit to Ohio, both

literally and figuratively. I had my eyes peeled for useful seeds

and was thrilled to stumble upon a patch of honey locust and

osage-orange growing together in a floodplain. It was easy to

gather up two big bags of osage-orange

fruits to turn into a hedge, but I had to do some serious foraging

to find un-gnawed honey locust pods. I take this as a very good

sign --- if the wild animals are so fond of honey locust seeds,

hopefully our

idea of feeding honey locusts to pigs will pan out.

The persimmon seeds were even easier to find. A medium-sized tree

near Mark's mom's house is always loaded when we go up for our winter

visit, and this time was no exception. I also pruned her grapes

and came away with a big handful of cuttings to turn into new

grapevines, assuming the scion wood lasts the winter in the root

cellar.

And, of course, the human part of the visit was great too.

We had a slight problem with one of the

retaining walls for the refrigerator

root cellar. It seems like a sturdy metal bracket will be needed to

secure the wall to the side of the refrigerator.

We had a slight problem with one of the

retaining walls for the refrigerator

root cellar. It seems like a sturdy metal bracket will be needed to

secure the wall to the side of the refrigerator.

You might notice a faint circle of melted snow around the chimney output. This was more noticeable a couple of hours ago, which is a nice way to illustrate how warm the air must be that's coming out.

It's awfully nice to visit friends and family, but when you live in the

middle of nowhere without a tv or neighbors, being in the outside world

is a lot like going to Disneyland --- overwhelming. Once we cross

our moat and come home, it takes two warm cats, a heavy snow, and a pot

of soup boiling on the stove to return to farm mentality.

Yes...tomatoes are now considered carnivorous

predators who kill insects in order to "self fertilize". Botanists

have recently discovered for the first time how the stem of

tomatoes has sticky hairs that can capture and kill small insects and

then absorb the yummy nutrients when the bugs fall to the ground and

decay.

Yes...tomatoes are now considered carnivorous

predators who kill insects in order to "self fertilize". Botanists

have recently discovered for the first time how the stem of

tomatoes has sticky hairs that can capture and kill small insects and

then absorb the yummy nutrients when the bugs fall to the ground and

decay.

Some people think this trait developed in the wild in an effort to

boost the nutrient levels in poor soil areas, but most domestic

varieties have the same ability.

The

farm got an inch of rain while we were away --- perfect conditions to

test out our

new swales.

So far, I'm quite impressed by how they're working. The ditches

(swales) have filled up with water, but the surrounding ground seems

firmer and less waterlogged than usual.

The

farm got an inch of rain while we were away --- perfect conditions to

test out our

new swales.

So far, I'm quite impressed by how they're working. The ditches

(swales) have filled up with water, but the surrounding ground seems

firmer and less waterlogged than usual.

Unfortunately, I don't

think the swales are quite big enough since the soil downhill still has

some standing water. Next time I'm working in that area, I'll

decide whether to deepen the swales, add a berm, or just add more

swales.

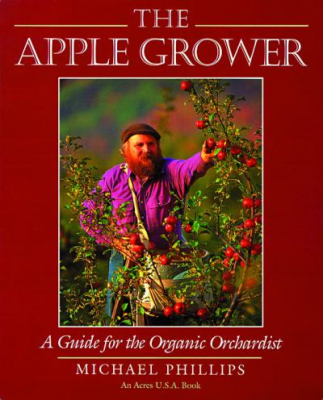

If you enjoyed my

series on traditional Central American farming practices, you'll love Farmers

of Forty Centuries

by F.H. King. Precisely 100 years ago, the American author

visited the eastern sections of China (along with Korea and

Japan). He documented his journey with

anecdotes, photos, and vivid prose like the following description of a

Cantonese house boat:

If you enjoyed my

series on traditional Central American farming practices, you'll love Farmers

of Forty Centuries

by F.H. King. Precisely 100 years ago, the American author

visited the eastern sections of China (along with Korea and

Japan). He documented his journey with

anecdotes, photos, and vivid prose like the following description of a

Cantonese house boat:

Sometimes husband and wife and many times the whole family were seen together when the craft was both home and business boat as well. Little children were gazing from most unexpected peek holes, or they toddled tethered from a waist belt at the end of as much rope as would arrest them above water, should they go overboard. And the cat was similarly tied. Through an overhanging latticed stern, too, hens craned their necks, longing for scenes they could not reach.

I'm excerpting the portions of the book which appeal to my organic gardening and permaculture leanings, but I highly recommend that you read the whole thing as an ultra-cheap Asian vacation. Although Farmers of Forty Centuries is currently back in print, you can still read the full text (minus the photos) for free on Project Gutenberg.

Check out our homemade chicken

waterers.

| This post is part of our Traditional Asian Farming lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The foot bridge suffered

a fatal error recently when the weaker walnut support cracked and

sagged, making it unsafe for anyone to use.

The foot bridge suffered

a fatal error recently when the weaker walnut support cracked and

sagged, making it unsafe for anyone to use.

We've decided to not rebuild it and instead upgrade the stepping stone

crossing and install a zip line for when the water would be over the

new steps.

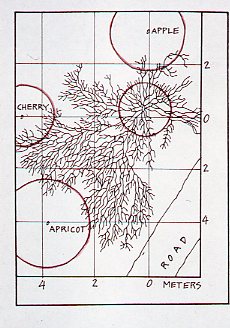

Our top choice for a pasture is the powerline

cut area down in the floodplain. The electric company chopped a

big swathe through the woods, and we can't let trees grow there, so we

might as well put it to use.

Our top choice for a pasture is the powerline

cut area down in the floodplain. The electric company chopped a

big swathe through the woods, and we can't let trees grow there, so we

might as well put it to use.

This weekend, I did some measuring and discovered that the open area

along the powerline is approximately one sixth of an acre. It

used to be farmed, long before we bought the land, so two ditches

bisect its width (and so does our driveway.) At the moment, I'm

thinking of using osage-orange

hedges to split the powerline cut into four paddocks along these

obvious dividing lines.

If we ever feel ready to have dairy animals, I've recently been

thinking our best bet would be miniature goats. They're short, so

fences don't have to be quite so intense, and they use less pasture per

animal so we might be able to fit in two does and a buck. With

four tiny paddocks, we'd be able to keep the buck separate and still

have room to rotate all the animals frequently to prevent overgrazing

and parasites. Of course, this is still very much in the dreaming

stages --- I expect our hedges to take anywhere from a year to five

years to be beefy enough to deter critters, and we still need to find

someone willing to milk when we're away from home!

In the early twentieth century when Farmers of Forty Centuries

was written, Asia was immensely overcrowded compared to the United

States. Chinese farmers only had about two acres of agricultural

land to feed each person, compared to twenty acres per person in the

U.S. In addition, many parts of China had been farmed constantly

for four thousand years --- clearly, Chinese farmers weren't

subscribing to American tactics of using the land hard then moving on.

In the early twentieth century when Farmers of Forty Centuries

was written, Asia was immensely overcrowded compared to the United

States. Chinese farmers only had about two acres of agricultural

land to feed each person, compared to twenty acres per person in the

U.S. In addition, many parts of China had been farmed constantly

for four thousand years --- clearly, Chinese farmers weren't

subscribing to American tactics of using the land hard then moving on.

Although many of the traditional farming practices outlined in Farmers of Forty Centuries

have probably been replaced by mechanization and chemical fertilizers

in the last century, I

think we still have a lot to learn from the book. Urban

homesteaders will be enthralled by traditions that allow a person to be

fed on as little as a sixth of an acre of prime farmland. And

those of us watching the U.S. population explode will be equally

interested since we currently have only about three acres of farmland

to feed each American.

So how did Chinese farmers feed themselves on such small farms?

Read on.

| This post is part of our Traditional Asian Farming lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

--- Errol, South Carolina

Thanks for the question.

Thanks for the question.

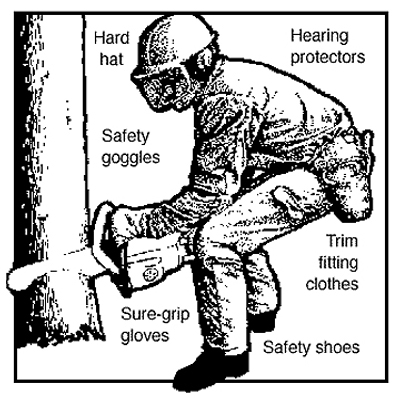

It didn't take me long to come up with an answer to this one. The Stihl

chainsaw would be my choice. You can get an attachment these days

that can turn any chainsaw into a heavy duty hedge trimmer, which would

be handy for clearing a new place. Firewood production would be my main motivation.

If you've got the time and talent a good chainsaw can also be used to make some impressive wood sculptures.

Most vegetable and annual flower seeds are

pretty easy to grow --- just throw them in the ground at something

close to the right depth at the right time of year and they sprout just

fine. When you start trying to plant tree, shrub, and perennial

herb seeds, though, propagation techniques often get a bit more

tricky. I always stumble when I'm told to scarify or stratify

seeds, but both techniques are actually quite easy, as I discovered

when I started looking up information about growing honey locusts

and persimmons from seed.

Most vegetable and annual flower seeds are

pretty easy to grow --- just throw them in the ground at something

close to the right depth at the right time of year and they sprout just

fine. When you start trying to plant tree, shrub, and perennial

herb seeds, though, propagation techniques often get a bit more

tricky. I always stumble when I'm told to scarify or stratify

seeds, but both techniques are actually quite easy, as I discovered

when I started looking up information about growing honey locusts

and persimmons from seed.

Persimmon seeds need to be stratified before they will germinate.

People try to make stratification more difficult than it actually is,

telling you to put the seeds in a pot of dirt or in a ziploc bag with a

wet paper towel and leave them in the fridge for a certain length of

time. In practice, I've discovered that native plants have

evolved to stratify quite nicely in the garden. Just plant the

seeds in the fall and they'll be exposed to plenty of cool temperatures

and will germinate as usual in the spring. I tried this with

persimmons a few years ago with good success and am trying again this

year.

Honey locust seeds, on the other hand, need

scarification to germinate. The problem is that many seeds

evolved to be eaten by animals and to pass through the gut relatively

unharmed. Seeds need thick coatings to survive the stomach acids,

but these thick coatings are often impenetrable to water, meaning that

your seed won't sprout unless it's scarified. The natural way to

scarify seeds is to pass them through some animal's stomach and let the

acids break partway through the seed coating. Barring a handy

animal, people will drop the seeds in a vat of acid or hot water, or

will manually damage the seed coat (hopefully without damaging the seed

inside.) I tried to file my honey locust seeds with no luck, and

instead ended up snipping through the edge of the seed coat with

fingernail scissors. This is my first attempt at scarification,

so I'm very curious to see whether it works!

Honey locust seeds, on the other hand, need

scarification to germinate. The problem is that many seeds

evolved to be eaten by animals and to pass through the gut relatively

unharmed. Seeds need thick coatings to survive the stomach acids,

but these thick coatings are often impenetrable to water, meaning that

your seed won't sprout unless it's scarified. The natural way to

scarify seeds is to pass them through some animal's stomach and let the

acids break partway through the seed coating. Barring a handy

animal, people will drop the seeds in a vat of acid or hot water, or

will manually damage the seed coat (hopefully without damaging the seed

inside.) I tried to file my honey locust seeds with no luck, and

instead ended up snipping through the edge of the seed coat with

fingernail scissors. This is my first attempt at scarification,

so I'm very curious to see whether it works!

Traditional Chinese

agriculture made extremely efficient use of space and time. One

trick they used was to apply heavy inputs of organic fertilizer,

allowing crop plants to be spaced very close together. (More on

the fertilizers tomorrow.)

Traditional Chinese

agriculture made extremely efficient use of space and time. One

trick they used was to apply heavy inputs of organic fertilizer,

allowing crop plants to be spaced very close together. (More on

the fertilizers tomorrow.)

Farmers also used

several techniques to tease two to four crops out of their farm each

year. They started most plants in seed beds so that space in the

main part of the farm was left open for an early season crop. A

typical rotation might include early season beans, followed by a grain

(such as the rice shown here). During the final month of a

grain's growth period, a third crop (like cotton) was often

interplanted so that the cotton could get a few weeks' head start on

the fall season. Those of us who are lax about our fall

gardens should take

heed!

As we all know, animals

require about five times as much land per calorie as vegetables do, so

it should come as no surprise that the traditional Chinese diet is very

low on meat. King noted that the primary meat animal was pigs,

which he explains convert plant matter to meat at the most efficient

rate.

And how about tree

crops? The best example of space-saving orcharding in the book

was the technique Japanese farmers used to raise pear trees. The

branches were trained to grow horizontally along an arbor just high

enough off the ground that farmers could walk underneath and easily

pick the fruit. Trees were spaced just twelve feet apart, and the

dense foliage shaded out most undergrowth. The technique sounds a

lot like espaliered

fruit trees to me.

| This post is part of our Traditional Asian Farming lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The refrigerator

root cellar suffered a set back last night during a heavy down pour.

The refrigerator

root cellar suffered a set back last night during a heavy down pour.

It should only take a few hours to dig back out, and the new plan is

to add a small roof like the one on our home

made firewood shed to prevent this from happening again.

Two and a

half inches of rain following a week of frozen ground means flood!

I'm working on my video

skills, so hopefully this one will be more

entertaining than my

previous flood video.

If you hate videos

(Mom), here's a photo of a snail I caught climbing a

wingstem stalk to escape from the rising waters. Also, feel free

to check out our newest feature --- a link to the week's top three most

visited articles at the bottom of the sidebar. If you go read all

three, it's almost like being popular!

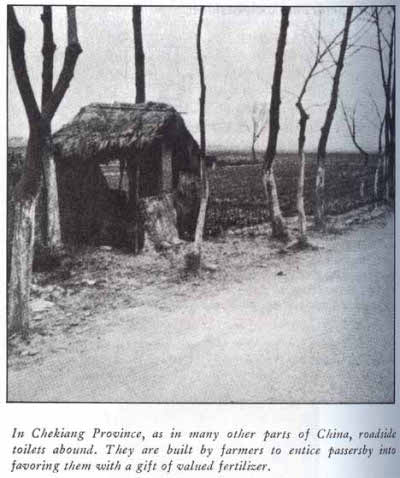

I have to admit that my

primary goal in reading Farmers

of Forty Centuries

was to discover whether farmers really put outhouses along public

roads, hoping to trap travelers into depositing their wastes

therein. The book gave me a resounding yes, and noted that

contractors also paid for the privilege of removing human waste from

cities so that they could sell the precious substance to farmers.

Humanure was often diluted with water and applied directly to fields or

dried and then applied in a powder form.

I have to admit that my

primary goal in reading Farmers

of Forty Centuries

was to discover whether farmers really put outhouses along public

roads, hoping to trap travelers into depositing their wastes

therein. The book gave me a resounding yes, and noted that

contractors also paid for the privilege of removing human waste from

cities so that they could sell the precious substance to farmers.

Humanure was often diluted with water and applied directly to fields or

dried and then applied in a powder form.

Of course, it took a lot

more than humanure to maintain the fertility of fields for thousands of

years. King saw farmers building huge compost piles, planting

nitrogen fixing plants (especially clovers) as a green manure, and

cutting plants from the hillside and grave mounds to apply to the soil

or to add to their compost piles. Just

like in Central America,  high fertility silt was

excavated from canals and applied to fields, and King noted that the

snails in the canal mud were also important in the fertilizing

campaign. Farmers scavenged animal wastes from the roadsides and

carefully husbanded any wastes from their own livestock, and they also

drained fish ponds at intervals so that they could scoop up the high

quality mud on the pond floor. The addition of ashes from their

cooking fires and all plant residues from their fields rounded out

their organic matter.

high fertility silt was

excavated from canals and applied to fields, and King noted that the

snails in the canal mud were also important in the fertilizing

campaign. Farmers scavenged animal wastes from the roadsides and

carefully husbanded any wastes from their own livestock, and they also

drained fish ponds at intervals so that they could scoop up the high

quality mud on the pond floor. The addition of ashes from their

cooking fires and all plant residues from their fields rounded out

their organic matter.

| This post is part of our Traditional Asian Farming lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

What happens when you don't tighten down the lug nuts on your golf cart

and drive for several weeks as they slowly loosen? The lug nut threads

get worn, creating a problem that requires a replacement.

A trip to the local hardware store proved the special nuts were not a

common item, but a regular one was that had the same thread ratio, and

to compensate for the lack of shoulder I just added a beefy washer.

We've been driving it this way for a couple of months now with no

problem.

I've

always been fond of Boxing Day...even though few people have actually

heard of it in the U.S. In the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia,

and New Zealand, the day after Christmas was traditionally a time for

people who could afford it to give a box of gifts to their poorer

neighbors. Granted, Boxing Day is now more akin to our Black

Friday, but I like the original holiday I read about in British

children's books during my formative years.

I've

always been fond of Boxing Day...even though few people have actually

heard of it in the U.S. In the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia,

and New Zealand, the day after Christmas was traditionally a time for

people who could afford it to give a box of gifts to their poorer

neighbors. Granted, Boxing Day is now more akin to our Black

Friday, but I like the original holiday I read about in British

children's books during my formative years.

Until I moved to the

farm, I was a bit of a vagrant, moving every year. The yearly

move gave me a great opportunity to go through all of my possessions

and cull out items that I really didn't feel like carrying up and down

several flights of stairs, donating them to Goodwill. Now that

we've been living on the farm for over three years, lack of a yearly

move has led to far too much clutter.

This week, Mark and I

started on our own version of Boxing Day. We each went through

our clothes with a fine-tooth comb, culling about half of them to be

given away. The result is immediate gratification ---

space! Next on my "Boxing Day" agenda will be culling my books,

the only other items that seem to build up in my living space.

In addition to lacking space,

China has a serious shortage of wood. Even a hundred years ago,

King noted that trees were scarce and small, and even those trees were

heavily utilized by cutting the lower limbs for firewood.

In addition to lacking space,

China has a serious shortage of wood. Even a hundred years ago,

King noted that trees were scarce and small, and even those trees were

heavily utilized by cutting the lower limbs for firewood.

As a result of the wood

shortage, most buildings were traditionally made out of straw and

clay. Although the straw and clay tended to need frequent

replenishing, the old building materials were perfect for throwing in

the compost pit.

Farmers were also very

good at utilizing other types of plants for fuel. Woody vegetable

stems (especially rice straw) were frequently burned. Although I

approve of making full use of the resources at hand, King's description

of the cooking fire requiring one person to constantly feed it small

bits of straw sounds like a bit too much work.

Otherwise, King made the

Chinese traditional agriculture system look so rosy that

I find it hard to remember that, a century later, farming looks a lot

different. If you're interested in what's happened in the last

hundred years, you should check out the overview

on Wikipedia.

| This post is part of our Traditional Asian Farming lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

A simple system that works well for our automatic chicken waterers

is to have at least 2 available for each group, that way if you forget

and leave one out overnight when it freezes you'll have the back up to

set out while the frozen one takes the day off by warming back up.

A simple system that works well for our automatic chicken waterers

is to have at least 2 available for each group, that way if you forget

and leave one out overnight when it freezes you'll have the back up to

set out while the frozen one takes the day off by warming back up.

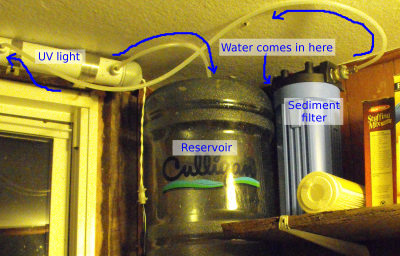

Although people used to live on our farm

during the Depression, the farm's only drinking water supply is a

shallow, hand dug well that tested positive for coliform

bacteria. Granted, many people drink from shallow wells and

springs just like this around here. You build up a tolerance and

tend to do just fine, but if you give water to unsuspecting visitors,

they get sick.

Although people used to live on our farm

during the Depression, the farm's only drinking water supply is a

shallow, hand dug well that tested positive for coliform

bacteria. Granted, many people drink from shallow wells and

springs just like this around here. You build up a tolerance and

tend to do just fine, but if you give water to unsuspecting visitors,

they get sick.

To avoid this problem, we spent our first year or two lugging drinking

water back to the farm. My mom would rinse out empty milk jugs

and save them for me, then we'd fill them up at her house when we went

to visit. Other times, we'd fill up our milk jugs at various

other friends' houses closer to the farm. Sometimes, we were able

to haul the jugs of water back to the trailer in our four wheel drive

truck, but a lot of the time the truck wasn't working and we'd just

carry them in --- it's not too hard to haul a jug of water in each hand

while walking Lucy in the morning.

Water feels more precious when the supply is limited. We cooked

and drank the special water, going through about a gallon a day between

us. For everything else, we used creek water, treated with some

bleach when we did dishes, but plain for other tasks.

Then we splurged on our water

filtration system and were blessed with unlimited, safe drinking

water. I felt like we'd moved from a third world country to a

second world country!

Then we splurged on our water

filtration system and were blessed with unlimited, safe drinking

water. I felt like we'd moved from a third world country to a

second world country!

The only flaw is that we still haven't quite gotten our water line

all the way buried since my wrists can't take much heavy digging and I

tend to set Mark on tasks that seem more important. So this week

we fell halfway back to our third world country. I dragged all of

the old milk jugs out of the barn, rinsed them out, and filled them up

with our treated water. By Friday, the freeze set in and we

started dipping into stored water.

It's funny to read on other peoples' blogs about disaster preparedness

--- people filling up empty milk jugs just in case the world comes to

an end or a heavy storm knocks out their power for days on end.

It doesn't really feel like a disaster to be pumping our drinking water

during thaws and drinking out of jugs during cold snaps. I guess

it's all a matter of perspective....

These past few days have been a real test for the new mud

traction golf cart tires. I thought the frozen ruts might create

too much of a challenge, but the ice isn't quite frozen through all the

way and seems to break easily with a dramatic crashing sound that sends

my imagination racing to an Arctic exploration story I once read.

We

love our dwarf Meyer lemon. We got it as a tiny tree two years

ago and ate

our first four lemons last February. We just got three

more lemons that turned into the most delicious lemon meringue pie, and

the tree still has four half-grown lemons and an explosion of flowers

on its branches.

We

love our dwarf Meyer lemon. We got it as a tiny tree two years

ago and ate

our first four lemons last February. We just got three

more lemons that turned into the most delicious lemon meringue pie, and

the tree still has four half-grown lemons and an explosion of flowers

on its branches.We've now met four other people who have dwarf Meyer lemons, and the reports are varied. Our neighbor has a several year old tree that had 91 lemons on it last year:

On the other hand, my

father's lemon tree is a year old with no sign of blooms or

fruits. Another friend's lemon tree looks even more puny.

What's going on?

I'm far from an expert

on dwarf Meyer lemons, but I'm starting to think that the trees require

heavy feeding and big pots. Our lemon tree is in a five gallon

pot that I filled with stump dirt, topped off later with worm castings,

and now fertilize regularly with compost tea from the worm bin.

My neighbor's amazing lemon tree is in an even bigger pot and he feeds

it Miracle Grow. On the other hand, the less happy trees I've

seen have all been in smaller pots. Remember, creating lemons

takes a lot of energy, so your tree needs plenty of nitrogen.

My advice, for what it's

worth --- transplant your lemon into a big pot and feed it, feed it,

feed it! Under the right conditions, dwarf Meyer lemons are a

great source of citrus for those in cold climates who want to grow

their own as a houseplant.

I think this is the design I've settled on for increasing the load

capacity of the golf cart. You can order the shiny

new metal version for about 350 dollars, or maybe a sheet of

plywood with a few 2x6's could become a nice low budget home made dump

box for your golf cart. Soon this project will move from my imagination

to the Wetknee drawing board once the storage

building project gets wrapped up.

My

post yesterday about care

of your Meyer lemon tree got long, so I didn't have

room to fit in what I've learned about cooking with the fruits.

Since Meyer lemons are actually a hybrid between a true lemon and an

orange, their flesh is a bit sweeter than the lemons you'd buy in the

store --- just sweet enough that sour-lovers like me can eat them

raw. When cooking with Meyer lemons, I tend to lower the amount

of sugar in the recipe a bit so that we're not overwhelmed with

sweetness.

My

post yesterday about care

of your Meyer lemon tree got long, so I didn't have

room to fit in what I've learned about cooking with the fruits.

Since Meyer lemons are actually a hybrid between a true lemon and an

orange, their flesh is a bit sweeter than the lemons you'd buy in the

store --- just sweet enough that sour-lovers like me can eat them

raw. When cooking with Meyer lemons, I tend to lower the amount

of sugar in the recipe a bit so that we're not overwhelmed with

sweetness.

I've also noticed that

the zest (grated rind) isn't as tangy as that on a true lemon.

Here I tend to cheat and throw in a bit of extra zest from a

storebought lemon. On the other hand, Martha Stewart will

tell you that the white part of a Meyer lemon isn't bitter, so you can

just cut up the whole lemon and put it in various dishes --- I'll have

to give that a try!

If you want to learn

more about the Meyer lemon, I recommend this

NPR article.

Did you know they've been grown as container plants in China for over a

century?

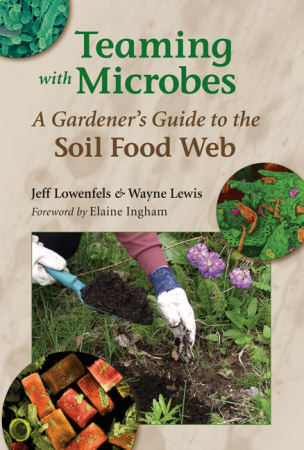

I was sucked into Teaming with Microbes by

Jeff Lowenfels and Wayne Lewis this weekend. Teaming with Microbes took

the information from my Living

Soil lunchtime series and turned it into what felt like a fast-paced action novel,

complete with stunning photos of the characters.

I was sucked into Teaming with Microbes by

Jeff Lowenfels and Wayne Lewis this weekend. Teaming with Microbes took

the information from my Living

Soil lunchtime series and turned it into what felt like a fast-paced action novel,

complete with stunning photos of the characters.

As you probably remember, a healthy soil food web equates to a healthy

organic garden. If you have the right critters in your soil,

you'll have better nutrient retention, better soil structure, and

better defense against diseases.

But Lowenfels and Lewis took the story one step further, explaining

that not every soil food web is created equally. Nor will one

type of food web make all plants happy. The key is to come up

with the right fungi to bacteria ratio for each garden.

| This post is part of our Teaming With Microbes lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I'll take

warm and muddy over cold and frozen any day.

Mark Twain: “Buy land. They’ve stopped making it.”

Seasteaders: “Production Resuming.”

Do you want to go back to the

land without being under the sway of the federal government? If

so, the Seasteading Institute

suggests you should instead go back to the water. They envision

intentional homesteading colonies constructed on floating platforms in

international waters. Out there on the sea frontier, you can do

whatever you want since no nations' laws apply.

Do you want to go back to the

land without being under the sway of the federal government? If

so, the Seasteading Institute

suggests you should instead go back to the water. They envision

intentional homesteading colonies constructed on floating platforms in

international waters. Out there on the sea frontier, you can do

whatever you want since no nations' laws apply.

The nonprofit is founded

by libertarians, and they bill seasteading as

a method of testing out new political systems. I can also see the

appeal of building your own nation from an entirely nonpolitical point

of view --- homesteaders everywhere wrestle with restrictive building

codes that don't allow them to build strawbale houses or composting

toilets. Wouldn't it be nice to be able to choose environmentally

sustainable options without jumping through months of hoops?

Mark's response was,

"One word: pirates." (Though

the Seasteading Institute thinks that pirates wouldn't be a big deal.)

And, granted, I'm far too attached to my hills to leave the land for

the sea. Still, I thought you all might be interested.

After all, the first colony is planned to go live in 2015.

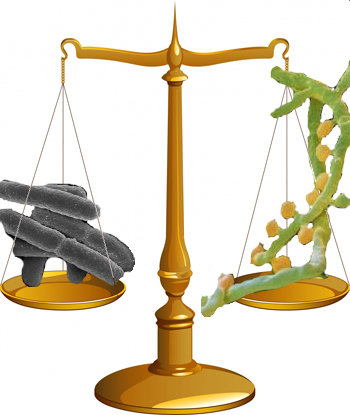

What is a fungi to bacteria ratio? The fungi to bacteria ratio

is simply the mass of fungi in the soil compared to the mass of

bacteria in the soil. In most cases, all you really need to know

is whether the soil is dominated by fungi, dominated by bacteria, or

has an even proportion of both.

What is a fungi to bacteria ratio? The fungi to bacteria ratio

is simply the mass of fungi in the soil compared to the mass of

bacteria in the soil. In most cases, all you really need to know

is whether the soil is dominated by fungi, dominated by bacteria, or

has an even proportion of both.

In nature, disturbed soils like those after a mudslide or in your

recently tilled garden have a strong bacterial dominance. As the

soil is left alone for a while, fungi start to move in until habitats

like prairies or your lawn have a relatively even proportion of fungi

and bacteria in residence. Later, as shrubs and trees take over,

the fungi in the soil build up even more so that forest soils are

strongly fungi dominated.

Scientists have started to look at the fungi to bacteria ratio

preferred by garden plants as well. They discovered that carrots,

lettuce, and crucifers enjoy strongly bacteria dominated soils while

tomatoes, corn, and wheat like soils that are closer to evenly matched

(though still leaning a bit toward bacteria.) On the other hand,

most perennials, shrubs, and trees like the soil to be full of fungi at

ratios from 10:1 to 50:1.

Clearly, folks like me who have been treating our trees just like our

lettuce beds need to stop!

| This post is part of our Teaming With Microbes lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Anna installed these entrance reducers in all

three hives today. Without this you run the risk of a mouse making

its way into your hive and making a sweet feast of all that delicious

honey.

I took advantage of

temperatures above 50 to check on our hives Tuesday. We've been feeding

sugar water pretty much continuously for the last six weeks,

stopping only when winter set in and started freezing our

feeders. My hive check showed that the girls have been

dehydrating the sugar water and packing it away very nicely --- we're

now up to 46, 64, and 69 pounds of honey in our three hives, which

should carry them all through the winter. I'm a little concerned

at the apparent lack of pollen in the hives, but hopefully our early

blooming hazels will provide pollen just as brood-rearing begins in the

spring.

Outside the hive, dozens

of dead bees litter the ground. Although it looks like a massacre

took place, this is perfectly normal. Every hive

cuts down its numbers in early winter, first kicking out the drones

then letting the older worker bees die as well. I guess that's

one way to control your population so you don't run out of food!

Why

do some plants like fungi around their roots while others like

bacteria? The answer takes us into the realm of chemistry...hang

in there.

Why

do some plants like fungi around their roots while others like

bacteria? The answer takes us into the realm of chemistry...hang

in there.

Most soil bacteria

secrete a slime that holds them to soil particles so

that the tiny microorganisms don't wash away. This slime tends to

be alkaline, so as bacteria build up, the soil pH rises above 7.

Meanwhile, the type of

nitrogen in the soil changes. Decomposers

in the soil excrete ammonium as a waste product, but when there are

lots of bacteria around, the bacteria convert the ammonium into nitrate.

On the other hand, soil

fungi secrete acids that they use to break down

organic matter, making it easier to digest. The acids in the soil

make the environment more difficult for bacteria to inhabit, so most of

the nitrogen in the soil stays as ammonium rather than being converted

to nitrate.

As every gardener knows,

plants care about pH. What many

gardeners don't realize is that plants also care about the form of

nitrogen they take up. Vegetables, annuals, and grasses tend to

prefer nitrate, while trees, shrubs, and perennials prefer

ammonium. Now we know why lettuce is going to throw a hissy fit

if the soil is full of fungi.

| This post is part of our Teaming With Microbes lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

This chicken

tractor is slated for upgrade in early 2010. I got a bit carried

away with the construction and ended up making it too heavy, which

creates a problem when dragging it to a new location.

This chicken

tractor is slated for upgrade in early 2010. I got a bit carried

away with the construction and ended up making it too heavy, which

creates a problem when dragging it to a new location.

The other problem is an issue of access. It really needs another door

close to the ground. That way if they escape you can coax them back in

easily with a bribe of chicken feed.

The

old house at the edge of the yard has been on its way out ever since I

bought the property. It was built with no foundation and no

structural elements except for thin walls, and yet it stood for three

quarters of a century. By the time I arrived on the property, it

had developed a bit of a lean and the porch and one room had collapsed,

but we probably could have shored it up. Mark wasn't in the

picture yet, though, and I knew nothing, so I commenced to tear it

down. Here's an animation showing me tearing down the second of

the four rooms:

The

old house at the edge of the yard has been on its way out ever since I

bought the property. It was built with no foundation and no

structural elements except for thin walls, and yet it stood for three

quarters of a century. By the time I arrived on the property, it

had developed a bit of a lean and the porch and one room had collapsed,

but we probably could have shored it up. Mark wasn't in the

picture yet, though, and I knew nothing, so I commenced to tear it

down. Here's an animation showing me tearing down the second of

the four rooms:

By

the time Mark stepped in and stopped me, I had torn the house down to

the original two rooms, then had ripped half the walls off what

remained. What little structure the house once had was long gone,

but the house stood for another year or two anyway. Finally, it

developed such a major lean that we were afraid it would fall on Lucy

in the night, so we yanked it down with the hand

winch, but never managed to take the time to disassemble it.

By

the time Mark stepped in and stopped me, I had torn the house down to

the original two rooms, then had ripped half the walls off what

remained. What little structure the house once had was long gone,

but the house stood for another year or two anyway. Finally, it

developed such a major lean that we were afraid it would fall on Lucy

in the night, so we yanked it down with the hand

winch, but never managed to take the time to disassemble it.

This week, I've finally put house demolition back on the to do

list. Mark's got the homemade

storage building

walls nearly complete, and then he'll be needing a roof. I figure

we can save about $200 by reusing the old tin, and that doesn't even

take into consideration the thick rafters that are already cut to just

the right length. Finally, the old house is worth taking apart.

I have to admit my ulterior motive, though. The old house sits on

some of the richest soil in our yard, ground that I've been eying for

years. By taking the house apart, I'll have yet more garden space!

So

how do we build vegetable gardens with soil dominated by bacteria while

creating fungi-dominated soil around our trees? The first step is

to start being more sophisticated about our mulch choices.

So

how do we build vegetable gardens with soil dominated by bacteria while

creating fungi-dominated soil around our trees? The first step is

to start being more sophisticated about our mulch choices.

Bacteria are good at

breaking down what composters like to call

"greens" --- grass clippings, food scraps, and even straw (since the

grain was cut while it was still growing and full of sugars.)

Bacteria also thrive on easy to digest manures. On the other

hand, fungi shine when given "browns" --- fallen leaves, wood chips,

and anything else full

of lignin and hard for most other organisms to

digest.

The consistency and

application method of the mulch matters too.

Wet, finely ground mulch supports bacteria, even if the mulch consists

of fallen leaves. On the other hand, dry mulch in big chunks will

encourage fungi. Any mulch that is worked into the soil will feed

bacteria first, while mulch placed on the soil surface will feed fungi.

So an optimal mulch for

a vegetable or annual flower garden would

probably consist of finely chopped, wet grass clippings. Under

our trees, the best mulch would be big chunks of leaves or wood chips.

| This post is part of our Teaming With Microbes lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Fire.

We now have the exterior

wood burning stove operating in the half finished storage

building. This must be what it felt like when early cave men

figured out that keeping your woman warm equals keeping her happy.

Since Mark

now has our wood stove up and running, I figured it was high time

to gather some kindling. The windy days last week knocked down a

lot of dead, dry branches out of trees in the floodplain, and it only

took a few minutes to pick up a heavy hauler load.

Since Mark

now has our wood stove up and running, I figured it was high time

to gather some kindling. The windy days last week knocked down a

lot of dead, dry branches out of trees in the floodplain, and it only

took a few minutes to pick up a heavy hauler load.

Last winter when the chainsaw wasn't working, we discovered that the

miter saw makes short work of small and medium-sized branches.

First, I broke all of the small branches over my knee, then I sawed

through the larger branches.

I was a bit shocked at how small one heavy hauler load of kindling

becomes once sawn to size --- the resulting pile was only about knee

high. That should be enough to start a week's worth of fires,

though. Warmth sure does make me happy!

Teaming

with Microbes

made it clear that we have to make some major tweaks to our mulching

and fertilizing campaign. The horse manure and grass

clippings we

apply to our vegetable garden beds are perfect, but next year we should

shred our tree leaves much more before applying them as a winter mulch.

On the other hand, I'm

starting to rethink whether I should have

applied

horse manure to our fruit trees. It sounds like heavy

mulches of rotting wood chips or leaves are more likely to lead to the

fungi dominated soil communities these trees prefer. At least we

didn't fall into the trap of trying to grow grass under our fruit trees

--- a big no-no since grass prefers bacteria while trees prefer fungi.

| This post is part of our Teaming With Microbes lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

These new peel and stick solar panels are more

efficient than the fragile glass panels and cost about 300 bucks less.

This new design allows for more robust applications, such as on the

roof of a golf cart without the fear of your expensive panel breaking.

Having the sun constantly charging your batteries prevents the sulfates

from building up and extends the life of the battery bank by a minimum

of 25%.

These new peel and stick solar panels are more

efficient than the fragile glass panels and cost about 300 bucks less.

This new design allows for more robust applications, such as on the

roof of a golf cart without the fear of your expensive panel breaking.

Having the sun constantly charging your batteries prevents the sulfates

from building up and extends the life of the battery bank by a minimum

of 25%.

Since a golf

cart is sometimes considered an electric car by the IRS you can

deduct a nice 30% of your solar investment and you may even qualify for

a few hundred bucks per year as a battery credit. These kits usually

cost about 1600 dollars, weigh about 4 pounds and take about 15 minutes

to install.

Add an inverter and it can double as an emergency back up power system

for your home if you can manage to park it close enough to reach an

extension cord to.

Anna's brother and site admin Joey filling in for my sister -- The blizzard of '09 has cut off power and snowed Anna in. With wood heat she'll be ok. I will try to get her on the phone for a farm update later.

Our

power and phone are out, and look like they'll stay out for the near

future. Honestly, the hardest thing for me about life without the

grid is an inability to blog. We've made it to town for a quick check in so that I can upload the masses of posts I've written while off the grid --- I've set them to autopost over the next couple of days so that you'll have something to read while we're out of touch.

Our

power and phone are out, and look like they'll stay out for the near

future. Honestly, the hardest thing for me about life without the

grid is an inability to blog. We've made it to town for a quick check in so that I can upload the masses of posts I've written while off the grid --- I've set them to autopost over the next couple of days so that you'll have something to read while we're out of touch.

Don't feel rejected if

your comments don't show up until I return to the internet and if I

don't respond to your emails. We're thinking of you, in between

our efforts to stay warm and dry. Meanwhile, Happy Winter

Solstice! Merry Christmas! And, if the electric company

doesn't bring us back to the mainstream by then, Happy New Year!

Many thanks also to Joey for letting you know we're alive and well.

Can't live without us? Download our microbusiness ebook and have some fun reading while waiting for us to come back.

This post is part of our Two Weeks Without Electricity series.

Read all of the entries:

|

The

trees started splintering before sunset on Friday. Heavy snow

weighed down their limbs and kept falling, heaping up four inches

deep. By dark, the wet snow took down an electric line somewhere,

and suddenly the trailer powered down. Off went the furnace fan,

the computers, the fridge. I called the phone company and was

informed that power is off all over the county and that they expect it

back on by Sunday at midnight.

The

trees started splintering before sunset on Friday. Heavy snow

weighed down their limbs and kept falling, heaping up four inches

deep. By dark, the wet snow took down an electric line somewhere,

and suddenly the trailer powered down. Off went the furnace fan,

the computers, the fridge. I called the phone company and was

informed that power is off all over the county and that they expect it

back on by Sunday at midnight.

The snow kept

coming. When we went to bed, it was already six inches deep, and

all night gunshot-like cracks heralded trees crashing down. I

slept fitfully and was out at dawn to assess the damage.

During power outages,

I'm constantly expecting a miracle --- the lights will flicker, the

fridge will hum, and we'll be powered again. At first light on

Saturday, I discovered that wasn't going to happen anytime soon.

Our powerline was down straight up the floodplain, across the garden,

and then up the powerline cut going the other way. I called my

mom to share the excitement, hung up, and then picked the phone back

up. It was dead.

I

don't want to overwhelm you with the whole story at once, so stay tuned

for part II soon. Until then, feel free to check out our

ebook about starting your own business and quitting your job.

This post is part of our Two Weeks Without Electricity series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Our

first full day without power brought us back to basics: animals, water,

food, and shelter. The animals, luckily, weren't too hard.

Huckleberry and Strider came bounding up to the trailer through snow

over their heads (nearly a foot deep now, but finally slacking off) and

Lucy pranced and played in the drifts.

Our

first full day without power brought us back to basics: animals, water,

food, and shelter. The animals, luckily, weren't too hard.

Huckleberry and Strider came bounding up to the trailer through snow

over their heads (nearly a foot deep now, but finally slacking off) and

Lucy pranced and played in the drifts.

The chicken tractors

were completely covered, and one had half-collapsed under the weight of

the snow. I brushed the tops clear and saw hungry hens eager for

their breakfast...once I'd shoveled out the tractor so they wouldn't

get their feet wet.

Without electricity, the

fan on our exterior wood furnace doesn't run, which means that most of

that heat dissipates into the great outdoors. Mark first rigged

an ingenious setup using a DC fan and the golf cart's battery banks,

but the plastic fan quickly melted out of whack and stopped running.

At this point, I gave up and curled myself under a sleeping bag on the

sofa with Huckleberry and a book. But Mark wasn't deterred.

He dusted off the generator, and soon we were back in business!

Lights, power, action! Heat! Even electricity to top off

the cold level in our fridge and freezer and keep our food safe.

Luckily, we had drinking water stored up, but food was going to be

difficult since we cook on an electric stove. It took most of the

next day for me to figure out how to cook in and on the wood stove,

ending up with food that wasn't charred at one end and cold at the

other. But at least we had the basics we need to keep the farm

rolling along.

Stay tuned for part III soon. Meanwhile, feel free to check out our ebook about starting your own business and quitting your job.

This post is part of our Two Weeks Without Electricity series.

Read all of the entries:

|

We bought the Champion 3000 watt generator about a year ago for back up power. I took it out of the box, made sure it was all there, and

installed the wheels and handle and pretty much forgot about it till

this past Friday when our power went out.

We bought the Champion 3000 watt generator about a year ago for back up power. I took it out of the box, made sure it was all there, and

installed the wheels and handle and pretty much forgot about it till

this past Friday when our power went out.

It was a great relief to feel its gas-powered throaty engine come to

life. We only have about 4 gallons of fuel on hand, so we decided to

ration our generator time to a few hours in the evenings. This way we

can alternate between the freezer and refrigerator, giving them each

about an hour of cooling off time, charge our laptop batteries, and

power the blower fans that send heat from our exterior wood burning

stove to the inner sanctum of the trailer. The new stove configuration

is able to keep the back room heated during the night without the fan

as long as we keep it fed with fresh firewood.

We've got a bit of kerosene, and nearly a full tank of propane as back

up for heating and cooking, but I don't think we'll need it if we're

able to get out tomorrow and top off our generator fuel.

I was most impressed with how easy this generator started. I barely

have to pull on the rope and it springs to attention.

I'm not sure when we can expect to have our electricity fixed, so I

guess I'll be expecting nothing and gearing up to be ready for anything.

This post is part of our Two Weeks Without Electricity series.

Read all of the entries:

|

By Saturday afternoon,

the snow was a bit mushy on the bottom layers. Trees began to

shake themselves like wet dogs, tossing off their mantle of wet snow

and turning back up to face the sky. The cracks of falling limbs

and trees slowed and finally stopped, and Sunday morning I decided it

was time to explore our world.

I

borrowed Mark's knee-high over-boots, put on damp jeans over dry fleece

pants, and headed out to see what the outside world looked like.

I had to cross the downed power line, which I had skittishly steered

clear of for the last day even though it was coated in snow and Lucy,

Huckleberry, and a deer had all trotted across with no problems.

This time I was determined, though. So I tucked Lucy's leash over

her back and took a running leap across the white snake of wire hidden

under the snow.

I

borrowed Mark's knee-high over-boots, put on damp jeans over dry fleece

pants, and headed out to see what the outside world looked like.

I had to cross the downed power line, which I had skittishly steered

clear of for the last day even though it was coated in snow and Lucy,

Huckleberry, and a deer had all trotted across with no problems.

This time I was determined, though. So I tucked Lucy's leash over

her back and took a running leap across the white snake of wire hidden

under the snow.

Nothing happened.

Lucy, of course, trotted

over the wire behind me and waited for me to pick back up her

leash. We trudged down the driveway, past dozens of fallen tree

limbs. Some trees had ripped their whole root masses up out of

the wet soil and toppled over, making me laugh that I'd thought a

little leaf raking would do any damage to the forest compared to this

catastrophe.

The cars were, luckily,

branch-free, but the driveway between our parking area and the public

road hadn't fared so well. I counted seven full grown trees

toppled across the driveway and when I reached the main road, I knew we

would be stuck on the farm for a while. Two trees had collapsed

across the asphalt within sight and the road was unplowed. I

began to suspect that the electric company's estimate of giving us back

our power by Sunday was a pipe dream.

Stay tuned for part IV. Meanwhile, check out our microbusiness ebook.

This post is part of our Two Weeks Without Electricity series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Monday

morning, I was bound and determined to get to town, if only to let my

mother know that we hadn't been wiped off the map. Mark and I

both geared up and filled our backpacks and hands with the bare

essentials --- chainsaw tools, mixed gas, empty gas jugs in case we

made it to town, my laptop for the same reason, two oranges in case we

got stranded on the way, and the chainsaw. We only have one pair

of waders between us at the moment, so Mark had to cross the creek,

change into his work boots, then toss the waders back across the cold

water to let me cross. I was very glad that he has a good

throwing arm.

Monday

morning, I was bound and determined to get to town, if only to let my

mother know that we hadn't been wiped off the map. Mark and I

both geared up and filled our backpacks and hands with the bare

essentials --- chainsaw tools, mixed gas, empty gas jugs in case we

made it to town, my laptop for the same reason, two oranges in case we

got stranded on the way, and the chainsaw. We only have one pair

of waders between us at the moment, so Mark had to cross the creek,

change into his work boots, then toss the waders back across the cold

water to let me cross. I was very glad that he has a good

throwing arm.

The driveway was just as

much work to clear as we'd thought. It took a couple of hours of

hard sawing and dragging to move the pines that had fallen across the

road, but the work was for naught. We got in the car...and

watched as its tires spun vainly on the icy snow.

My

next thought was to walk to the neighbor's house a quarter of a mile

down the road and beg the use of their phone. The public road had

been plowed, but was seriously icy, making me glad that our little car

hadn't made it out of the driveway. Along the way, we ran into

another neighbor who gave us the bad news --- everyone in the area has

no power or phone. The electric company is hoping to restore the

juice by Christmas to those on the main road, which I figure leaves us

looking at New Years. Time to hunker down for the long haul.

My

next thought was to walk to the neighbor's house a quarter of a mile

down the road and beg the use of their phone. The public road had

been plowed, but was seriously icy, making me glad that our little car

hadn't made it out of the driveway. Along the way, we ran into

another neighbor who gave us the bad news --- everyone in the area has

no power or phone. The electric company is hoping to restore the

juice by Christmas to those on the main road, which I figure leaves us

looking at New Years. Time to hunker down for the long haul.

Stay tuned for part V soon. Meanwhile, check out our ebook that gives the secret of not worrying that your boss is going to fire you while you're incommunicado for a week or two.

This post is part of our Two Weeks Without Electricity series.

Read all of the entries:

|

When we learned that

electricity was a long way off, I decided it was high time to start

really cooking rather than hastily heating up leftovers and hot dogs in

the wood stove. Our exterior wood stove is singularly ill-suited

for cooking, with a sleeve around the stove providing hot air to be

blown indoors and also preventing the surface from reaching cooking

temperatures. The inside is generally far too hot to cook in

without charring.

But I had nothing else

to keep me busy, so I decided to create my own Dutch oven. I dug

up an old roasting pan out of the barn, set it up on a cinderblock, and

filled it with hot coals shoveled out of the wood stove. A pizza

pan fit well on top, and a big lid enclosed the heated surface. I

had moderate luck "baking" chocolate chip cookies but great luck frying

up bacon. Maybe the latter tasted so good because of the bit of

leftover chocolate melding with the bacon juices?

Meanwhile,

I was starting to get worried about our water situation. We still

had seven jugs of drinking water, but I could easily see us running out

and the dirty dishes were stacking up. I was pleased to discover

that packing a pot full to the brim and then half again as high with

clean snow melted down to a nearly full pot of warm dish water in three

hours on the wood stove. I added a bit of bleach for safety and

revelled in the feel of warm water on my hands as I cleaned up the

dishes.

Meanwhile,

I was starting to get worried about our water situation. We still

had seven jugs of drinking water, but I could easily see us running out

and the dirty dishes were stacking up. I was pleased to discover

that packing a pot full to the brim and then half again as high with

clean snow melted down to a nearly full pot of warm dish water in three

hours on the wood stove. I added a bit of bleach for safety and

revelled in the feel of warm water on my hands as I cleaned up the

dishes.

In a pinch, we probably

could have gotten away with drinking the melted snow, but our generator

made that unnecessary. We've allotted ourselves an hour and a

half of generator time every evening, plenty of time to turn on our

drinking water pump and UV light to fill up another dozen or so milk

jugs. And time to feed my blogging bug!

This is the last installment on the Monday CD. Stay tuned for more details soon (I hope.) Meanwhile, check out our microbusiness ebook.

This post is part of our Two Weeks Without Electricity series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Monday

night as we read by solar flashlight, the telephone rang! I'm a

confirmed phone-o-phobe, but that sound was the nicest one I'd heard in

days. I leapt up and pounced on the receiver, then enthused in my

father's ear, called my Mom and sister, and even talked to my equally

phone-phobic brother.

Monday

night as we read by solar flashlight, the telephone rang! I'm a

confirmed phone-o-phobe, but that sound was the nicest one I'd heard in