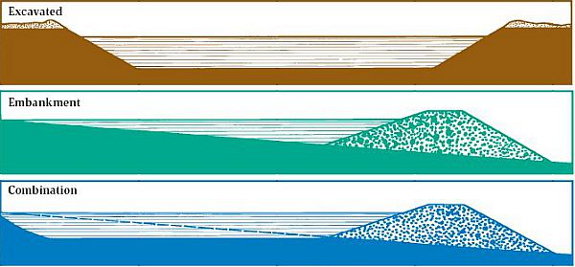

Types of earth ponds

Tim Matson explains

that there are two types of earth

ponds --- the

dug-out pond and the embankment pond. The former is

generally built in a flat area where groundwater lies close to the

surface, while the latter works best in a valley that can be

turned into a pond by building a wall across the valley bottom.

Tim Matson explains

that there are two types of earth

ponds --- the

dug-out pond and the embankment pond. The former is

generally built in a flat area where groundwater lies close to the

surface, while the latter works best in a valley that can be

turned into a pond by building a wall across the valley bottom.

Dug-out ponds are

just what the name suggests --- a hole in the ground. They

can be quite small, and commercial fisheries often use a series of

dugout ponds in series rather than one big pond to make management

easier. In the case of the fisheries Matson mentioned in his

book, ponds are about 15 feet in diameter and 3 to 5 feet deep.

The main disadvantage

of a dug out pond is that the earth needs to go somewhere else ---

mounding it up around the sides just creates a really

funny-looking pond in a hole. If you live in a very wet

area, though, that excavated soil can be a pro rather than a con

--- Matson mentioned one farmer who dug out a pond in a very low

area, then used the soil to bring a nearly-as-low field out of the

marsh and into more productive conditions. We're

doing something similar on a much smaller scale with our pond

experiment.

The embankment method

is often used to create a larger pond since it's more

cost-effective to mound up the excavated earth as a dam, raising

the potential water level and increasing your volume twice as

quickly for each scoop of earth removed. However, embankment

ponds often blow out at the dam if you're not careful, so you'll

want to follow Matson's tips to clear the embankment area down to

the subsoil, then slowly build it up with impervious soil,

compacting after every foot or two. Unlike the walls of a

dugout pond, which can be as steep as 2:1, you should keep your

embankment flatter, with a maximum slope of 3:1.

In both the case of a

dugout pond and an embankment pond, you need to think about how

water comes into and leaves the pond as well. Some dugout

ponds are sky ponds, relying completely on groundwater and rain to

stay full, but most ponds of both types are fed by a spring or

stream. Planning your inlet pipe so water cascades out onto

the pond surface will add oxygen, while burying the pipe keeps

water cooler in the summer and from freezing in the winter.

On the other hand,

you can use an unpiped inflow with a small settling pool just

before you reach the pond, preventing silt from entering the pond

proper.

In both the case of a

dugout pond and an embankment pond, you need to think about how

water comes into and leaves the pond as well. Some dugout

ponds are sky ponds, relying completely on groundwater and rain to

stay full, but most ponds of both types are fed by a spring or

stream. Planning your inlet pipe so water cascades out onto

the pond surface will add oxygen, while burying the pipe keeps

water cooler in the summer and from freezing in the winter.

On the other hand,

you can use an unpiped inflow with a small settling pool just

before you reach the pond, preventing silt from entering the pond

proper.

At the other end of

the pond, Matson is less keen on piping, having seen far too many

ponds leak around the outflow pipe. Instead, he recommends

creating a stone-lined spillway channel, or, if you absolutely

must pipe your outflow, adding an anti-seep collar around the

pipe.

Stay tuned for

tomorrow's post on sealing the earthen pond!

| This

post is part of our Earth

Ponds lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.