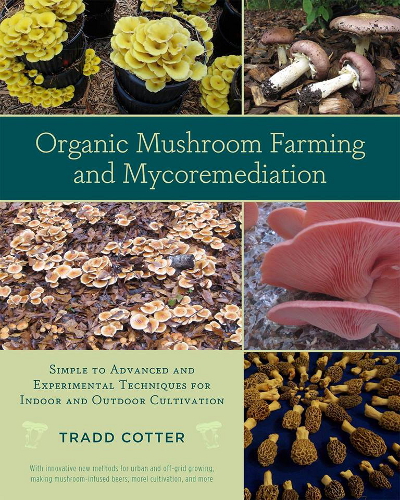

Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation

Although Tradd Cotter's Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation deserves a full lunchtime series...I already wrote one after listening to his inspiring lectures.

So, instead, I'll simply tell you that this beautifully illustrated

book is a must-read for anyone interested in homestead-scale mushroom

production. You'll learn more in-depth information about many of the

home-propagation techniques I've posted about previously, will be

inspired to try out mycoremediation

in your chicken coop, and much more. Then dive deeper into topics like

producing a slurry of morel spores and associated microbes to grow this

elusive species at home, or experiment with propagating shiitakes

without a lab by stacking thinly sliced logs separated by pieces of damp

cardboard.

Although Tradd Cotter's Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation deserves a full lunchtime series...I already wrote one after listening to his inspiring lectures.

So, instead, I'll simply tell you that this beautifully illustrated

book is a must-read for anyone interested in homestead-scale mushroom

production. You'll learn more in-depth information about many of the

home-propagation techniques I've posted about previously, will be

inspired to try out mycoremediation

in your chicken coop, and much more. Then dive deeper into topics like

producing a slurry of morel spores and associated microbes to grow this

elusive species at home, or experiment with propagating shiitakes

without a lab by stacking thinly sliced logs separated by pieces of damp

cardboard.

I really can't do Tradd's

book justice in a single post, so I'm merely going to sum up some

information on which mushroom species are best to grow in specific ways.

Tradd has a great section at the end of the book giving

species-by-species cultivation techniques for twenty-four types of

mushrooms, and he also breaks the species down into difficulty

categories. Based on that data, raw beginners who want to fruit their

mushrooms outdoors should consider black poplar mushrooms, wood ears,

reishi, brick tops, oysters and elm oysters, shiitakes, stropharia, and

turkey tails.

The book also clued me in to why my rafts

didn't do as well as I thought they would --- only reishi, nameko,

black poplar, brick top, and maitake are recommended for this type of

cultivation. Stumps,

similarly, are best for maitake, chicken of the woods, reishi, enoki,

oysters, and beefsteaks, with the tradeoff being that stumps take longer

to start to fruit than logs do, but that they then tend give you many

more years of harvests before petering out. Finally, if you want to grow mushrooms on cardboard, oysters, blewits, and stropharia are a good choice (at least during the vegetative stage).

Although I have a

tendency to focus on the easiest types of mushroom growing (namely

oysters and shiitakes seasonally fruiting on logs), Mark likes the idea

of faster production using sawdust, wood chips, coffee grounds and other

substances in containers. And Tradd succeeded in knocking out one of my

roadblocks to Mark's proposal, namely the constant use of throwaway

plastic bags. Instead, the mushroom guru recommends putting your growing

substrate in PVC pipes, nursery pots, or five-gallon buckets, all of

which can be modified with holes and sanitized in a 10% bleach-water

solution to allow reuse. Using these methods, you can see mushrooms as

soon as three weeks after inoculation when growing oysters on coffee

grounds --- too bad we don't drink that beverage or have a coffee shop

nearby!

In the end, Tradd's book is just as inspiring as his lectures were, but

the contents are much more meaty. I read the book slowly over the course

of a couple of months and recommend you do the same to enjoy the full

effect. Other mushroom books --- notably those by Paul Stamets --- will be a good supplement for the mushroom enthusiast, but Organic Mushroom Farming and Mycoremediation

has now risen to the top of my list of recommended mushroom books for

the homestead fungiphile. This book will be staying on my shelf for

years to come and I expect it will inspire many mushroom experiments.

Stay tuned for details as we try to propagate shiitakes using the log

method and perhaps grow some oyster mushrooms on old jeans.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

- Remove comment