Making a gate frame with treated 2x4's

I think I've found an easier

way of making a gate frame for our chicken

pastures.

Each side piece is a standard

8 foot long treated 2x4 that gets sunk in the ground at a depth of

about 19 inches. The top piece is cut to a 5 foot length.

Treated furring strips

attached in a rectangle shape make a good gate that's light weight and

low budget. I'm guessing the total price for this project is somewhere

between 15 and 20 dollars. Not sure what the longevity will

be like, but I'm thinking it might be comparable to a cedar post. I

guess I'll know the answer in another 10 to 30 years.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

If you look at framework constructions you will see triangles everywhere. The reason for that is that a triangle is a stable structure even if the beams are just pinned together.

To make a rectangular structure resist shear deformation you have two choises; either you add a diagonal brace to convert it into a combination of two triangles, or you nail triangular plates to the corner so that the corner can withstand shear deformation.

As Trevor noted, if you add a diagonal brace from the top hinge to the opposite bottom corner (the side of the door with the latch and opposite the hinges will tend to sag), this brace is only loaded in tension and thus self-straightening and can be as simple as a steel wire.

Thanks for all the shoring up ideas. I agree the gate will sag over time, and I guess I'm going to let it sag and then see if I need to implement one of the upgrades at that point.

Rebecca-Those little metal corner brackets sound like one of the easier ways to shore up the design, which I might do in the future when it starts sagging.

Roland-That steel wire idea is what I was thinking yesterday with the addition of one of those turnbuckle dohickeys that allow one to tighten the tension.

Hey Shannon,

Thanks for adding your voice to this thread....I'm still curious to hear how your search for a gravity wave is fairing?

I agree with you about using steel wire, it's just that I don't have any turnbuckle things handy and it would require a trip to the hardware store, but the main reason I'm putting it off for the future is the 100 other things pressing on the honey-do list. Right now I'm just going to focus on finishing the fence for that pasture, installing a 5 gallon bucket waterer, and fixing the gaps near the ground, and then moving on to whatever is next on the list.

Well, gravity wave searches are on hold while we do upgrades. We'll be searching again come 2014 or so...

As for no turnbuckles being handy... there's an old fence trick you can use. Take two strands of steel wire between the upper hinge and the bottom corner. Screw them to the wood, or just twist them into place. It helps if you install them so that there is a gap between them, maybe to the opposite outside edges of the wood. Then, you take a sturdy stick, place between the two strands of steel wire, and start twisting. Once it is tight enough to resist sag, you tie off one end of the stick.

Kind of like this:

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-pXvn6nuqmtM/Tb6h003tp9I/AAAAAAAAAjs/ekU35ifQhGE/s1600/DSC_0947.JPG

or this:

http://www.trublufence.com/images/hbrace.jpg

The stick is apparently known as a twitch stick, which I didn't know before tonight. http://www.ehow.com/how_8565101_secure-twitch-stick.html

I've been thinking about everyone's comments, and I think there are two points you're all missing. First, if used like a screen door, a very thin-framed door will sag really fast, but this isn't quite the same. The latch on one side holds that edge up to match the hinge side, which is probably why Mark's furring strip door with absolutely no cross-bars at all isn't sagging all that much 18 months later.

Second, remember this is for a chicken pasture. We're not building the Taj Mahal. If the doors last without sagging for two years and then I have to ask Mark to add a cross-brace, they've done their job well!

If the doors last without sagging for two years and then I have to ask Mark to add a cross-brace, they've done their job well!

Roland --- Excellent point. At the moment, we're willing to use treated wood in areas far from the garden like this, figuring it's no more harmful to the environment than the alternative (which, belowground, means using concrete, which has a lot of energy costs to produce, and aboveground would presumably mean painting repeatedly, which again has potentially environmental problems.) Cedar posts would be a good alternative (although I wonder whether the antifungal compounds that keep the wood from rotting also hurt soil microorganisms --- I'm not sure anyone has studied that.) My experiments with cedar posts, though, show that we have to use the relatively large trees since only the heartwood is rot resistant, which seems wasteful for a project like this.

John --- Mark's gate frame has quite a bit of structural integrity due to the cross-piece at the top and then the fencing wire on each side. Sure, it might move a bit if the ground freezes and thaws, but we haven't had trouble with other gate frames like this moving out of true. What Mark neglected to mention, though, is that he compacts the earth around each post when he backfills it with extreme vigor. He's a pro with what he calls a spud bar and what other people call, I believe, a tamping bar. By the time he's got a post in, it's in.

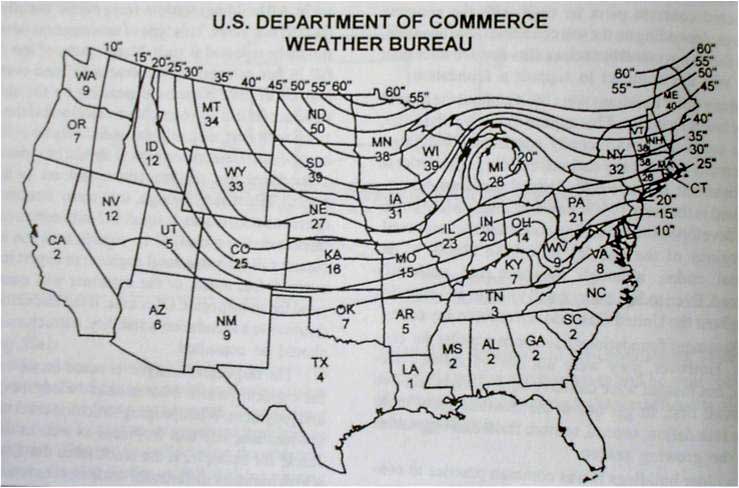

Good point, Rebecca, although southern Virginia actually has very variable frost depths depending on whether you're in the mountains or not. Our part of Virginia is equivalent to eastern Maryland. The map below should be helpful for the general idea of which areas have deeper frost penetration than others. (I've seen maps that give the frost depth as twice that shown below, but no matter which numbers you use, the relative frost depths stay the same.)