How to process wild clay

Jenn and I attended a

fascinating workshop at the Dairy Barn Saturday about digging clay out

of the earth and turning it into pottery. I was surprised to learn how

simple it is to process wild clay...although the techniques can be

quite time-consuming.

The first step is to

collect your clay. For best results, gather clay from within twenty

inches of the surface since this weathered clay will do better. You're

likely to find gray clays under coal seams and red clays elsewhere.

Both are good pottery clays if you live in our area.

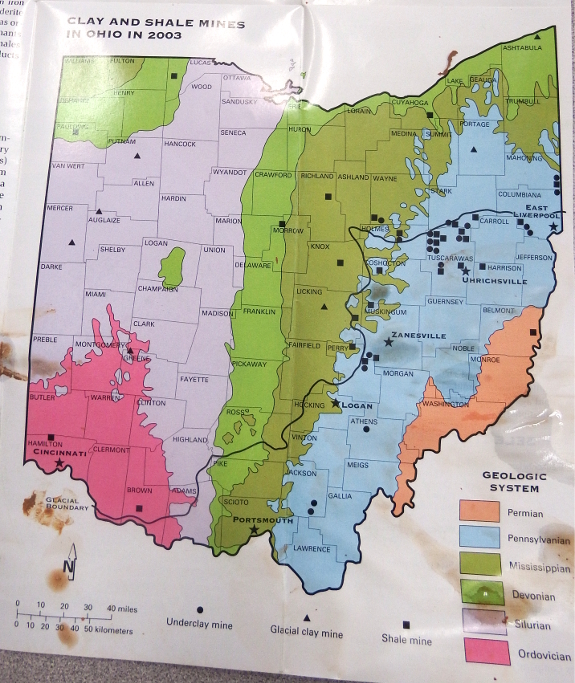

In fact, I was surprised

to learn that southeast Ohio is the clay capital of the world! Over

half the pottery made worldwide in the last one hundred years began as

clay in Ohio soil.

Okay, geography lesson

over. What do you do with your wild-sourced clay?

First, let it dry out

thoroughly. Then break the big lumps into smaller pieces, removing

pebbles and roots in the process. The most important pieces to take out

are small inclusions of limestone (the paler lump on the left in the

photo above) since limestone messes with the moisture content of clay

and can cause explosions in the kiln.

Breaking up the clay can

be done with your hands or with a hammer on the small scale. On a

larger scale, you'll want to use a hammermill of some sort.

Next, you'll have to

choose whether to wet-screen or to dry-screen your clay. Wet screening

is safer --- inhaling clay dust can make you very sick. But dry

screening is much easier to mechanize and perform in bulk using a

20-mesh screen shaken by an off-balance motor.

We wet-screened in our

workshop. First, add water...

Then mix with a spoon or

by hand. By hand is messy but much more effective.

Your goal is to achieve

milkshake consistency, working all of the little lumps into the main

mass of clay. On a medium scale, you can do this mixing in a bucket

with a dry-wall mixer drill attachment a

bit like this. Or

just squeeze it through your fist over and over on the small scale.

As a side note, if your

clay isn't very dry, it's actually much harder to moisten thoroughly.

In this case, drop the clay in a bucket of water and leave it for a few

days to soak up the liquid rather than trying to force water in quickly.

Now it's time to pass

the wet clay through a screen to pull out the last of the rocks and

roots. I found that it's easiest to press the wet slip through the

sieve with my fingers.

Then put the screened

clay on a board to dry somewhat (as in the photo at the top of this

post) and it's ready to use in hand-building, brick-making, or thrown

pottery. Our teacher suggested firing at cone 04 for most clays in our

area.

How about you? Have you

ever processed wild clay?

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

- Remove comment

- Remove comment