Grasses and legumes for intensive pastures

When I started my adventures

with chicken pasturing, I tried to micromanage the pasture, adding in

plants that I knew chickens

liked to eat.

In stark contrast, Joel Salatin believes that the most important

characteristic of chicken pastures is a very short sward and that the

individual species aren't as important. The list below introduces

a few of the common pasture grasses and legumes that seem to combine

both characteristics --- easy digestibility and the ability to survive

close grazing or mowing.

When I started my adventures

with chicken pasturing, I tried to micromanage the pasture, adding in

plants that I knew chickens

liked to eat.

In stark contrast, Joel Salatin believes that the most important

characteristic of chicken pastures is a very short sward and that the

individual species aren't as important. The list below introduces

a few of the common pasture grasses and legumes that seem to combine

both characteristics --- easy digestibility and the ability to survive

close grazing or mowing.

Kentucky

bluegrass is

ideal for intensive rotational grazing because it

can handle close grazing and some mismanagement. The species

wants to produce most of its growth in the spring and then slow down in

midsummer, but with good management, Bill Murphy attests that you can

get much more uniform

yields. Kentucky bluegrass shouldn't be confused with Canada

bluegrass, which provides less and lower quality forage for livestock,

but which does better in poor soil.

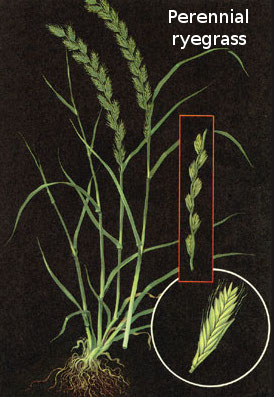

Perennial

ryegrass is an

ideal pasture grass if you live in zone 5 or

warmer and can provide high nitrogen and moist growing

conditions. The leaves contain a lot of  nonstructural

carbohydrates, which means they're very digestible and might be a good

choice for chickens.

nonstructural

carbohydrates, which means they're very digestible and might be a good

choice for chickens.

Orchardgrass can handle moderate soil

fertility and low moisture, but

it tends to get tall and inedible quickly if not grazed

carefully. If you have orchardgrass, you'll need to graze early

and often since chickens can't digest tough leaves.

Timothy has a lot of advantages,

being very palatable, persistent, easy

to establish, and tolerant of poor drainage. However, the grass

can't

handle drought and has a low yield. Timothy is a taller grass

than the others mentioned here, but can tolerate close grazing.

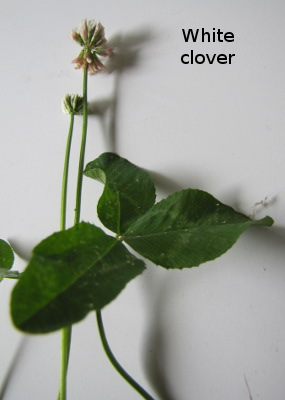

White

clover is the

primary legume in management intensive pastures

since it survives close grazing and grows quickly. When mixing

grasses with white clover, you need to graze or mow the grasses closely

in the spring so that they don't shade out the legumes.

Red clover is

more deep-rooted and can withstand drought, but is also more upright,

so

can't deal with close grazing. Alfalfa is even more deep-rooted,

but can't handle frequent grazing, requiring a 25 to 30 day recovery

period even in the spring.

Red clover is

more deep-rooted and can withstand drought, but is also more upright,

so

can't deal with close grazing. Alfalfa is even more deep-rooted,

but can't handle frequent grazing, requiring a 25 to 30 day recovery

period even in the spring.

Gene Logsdon's All Flesh

is Grass is

sitting on my shelf waiting to provide my continued pasture

education. A quick flip through the book suggests that it will

give additional information on good pasture species, so I'll write more

on that topic later this fall. In the meantime, I'm

inclined to believe that Joel Salatin and Bill Murphy know what they're

talking about --- even young, tender fescue leaves are probably

more tasty to chickens than old bluegrass leaves from plants gone to

seed.

| This post is part of our Greener Pastures on Your Side of the Fence

lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

- Remove comment

- Remove comment