Gardening for health and peace

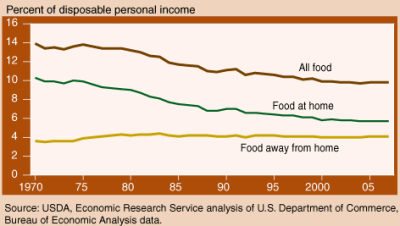

It

probably seems a bit strange to some of you to commit so much energy to

thinking about agriculture as the root of societal woes. After

all, most people in the developed world are so cut off from food

production that a cashier at our grocery store this spring had to ask

me to identify the asparagus in my cart before she could ring it

up. Thanks to government subsidies and externalization of the

true environmental effects of agriculture, modern agribusinesses feed

Americans at a cost of only about 9.8% of our income (5.7% for food

eaten

at home), a rate that has been steadily declining since 1970.

Modern agriculture means that food is easy and cheap --- who cares

about the historical problems associated with farming?

It

probably seems a bit strange to some of you to commit so much energy to

thinking about agriculture as the root of societal woes. After

all, most people in the developed world are so cut off from food

production that a cashier at our grocery store this spring had to ask

me to identify the asparagus in my cart before she could ring it

up. Thanks to government subsidies and externalization of the

true environmental effects of agriculture, modern agribusinesses feed

Americans at a cost of only about 9.8% of our income (5.7% for food

eaten

at home), a rate that has been steadily declining since 1970.

Modern agriculture means that food is easy and cheap --- who cares

about the historical problems associated with farming?

We should care.

Because, as the National

Institute of Health

wrote, "Over the next few decades, life expectancy for the average

American could decline by as much as 5 years unless aggressive efforts

are made to slow rising rates of obesity." Because that cheap

food in the grocery store also results in malnourishment and starvation

in the world's less developed countries, where peasant farmers grow our

shrimp and beef but can only afford to eat our cheap corn. Only

the truly short-sighted can believe that the ketchup we buy for pennies

at Food City doesn't have strings attached.

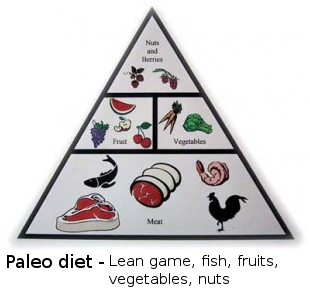

Luckily, there is a

solution. We can overcome many of the evils associated with

mainstream agriculture by planting our own backyard garden. Most

of us will plant vegetables, perhaps some fruit and nut trees, and keep

a few pastured poultry --- if we subsisted solely on produce from such

a homestead, our health would improve markedly. Permaculture and

organic gardening --- while only moderately suited to industrial scale

agriculture --- work perfectly for the home grower, allowing us to

create a sort of hybrid farmer/hunter-gatherer paradise in our own

backyard. If we raised our own pastured meat and killed deer to

fill in the gaps, those Third World farmers wouldn't be stuck in a trap

of spiralling malnutrition.

Luckily, there is a

solution. We can overcome many of the evils associated with

mainstream agriculture by planting our own backyard garden. Most

of us will plant vegetables, perhaps some fruit and nut trees, and keep

a few pastured poultry --- if we subsisted solely on produce from such

a homestead, our health would improve markedly. Permaculture and

organic gardening --- while only moderately suited to industrial scale

agriculture --- work perfectly for the home grower, allowing us to

create a sort of hybrid farmer/hunter-gatherer paradise in our own

backyard. If we raised our own pastured meat and killed deer to

fill in the gaps, those Third World farmers wouldn't be stuck in a trap

of spiralling malnutrition.

A couple of weeks ago,

Mark and I met a man who regaled us with the tale of his struggle to

conquer diabetes. He was 80 pounds overweight when his doctor

prescribed insulin, but through daily exercise and a strict diet, he

dropped the excess pounds and avoided medication. We ran into

this determined soul as he worked his second job --- a weekend addition

to the usual 9 to 5 grind that he took on not for the spare cash but

because he needed a way to mentally escape the pressure cooker of his

main job. "You must have a big garden?" we asked him, thinking of

how the fresh food would make his strict diet more palatable, how he

could put some of those hours of excercise to work building something

tangible, and how planting and weeding would help him release the

stress of his office work. The man looked at us as if we were

crazy. No, of course he didn't have a garden --- he simply didn't

have time.

Lack of time

to grow our own food

is the neverending refrain I run into among people who care deeply

about world peace and the environment. We have been lulled into a

false belief that gardening is simply not important, that our personal

actions make no difference in the grand scheme of things, that our time

is better spent pecking away at the keyboard in pursuit of a buck or

relaxing in front of the TV. Even Mark and I fall into that trap

from time to time, and we admit that we are still a long way from the

food self sufficiency we crave. But we know that every successful

experiment is a step in the right direction and every failure is time

well spent.

Lack of time

to grow our own food

is the neverending refrain I run into among people who care deeply

about world peace and the environment. We have been lulled into a

false belief that gardening is simply not important, that our personal

actions make no difference in the grand scheme of things, that our time

is better spent pecking away at the keyboard in pursuit of a buck or

relaxing in front of the TV. Even Mark and I fall into that trap

from time to time, and we admit that we are still a long way from the

food self sufficiency we crave. But we know that every successful

experiment is a step in the right direction and every failure is time

well spent.

By the way, if you live

in zone 6 or warmer, you can still plant fall greens if you

hurry. Or just put down a cover crop or kill mulch to jump start

the spring bounty. Gardening does matter, and we can each be part

of the solution...if we have enough time.

This post is part of our History of Agriculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

That's a very good point, and I've been thinking a lot about that. I agree that gardening is, technically, agriculture. But the result of backyard gardens seems to be the exact opposite of the results of industrial agriculture, and even of early traditional agriculture. Rather than putting power into the hands of a few, backyard gardens disperse that power. Rather than feeding us lots of grain and making us unhealthy, backyard gardens feed us vegetables and make us healthy.

Even the way we interact with our gardens is different if you use a permaculture and organic gardening perspective. My daily routine in the garden does involve lots of weeding (just like early agriculture), but other parts of my routine are a bit like the routine of Amazonian hunter-gatherers in their anthropogenic food forests. I stumble across a plump cucumber while feeding the chickens and stick it in my pocket for lunch. I nibble on ripe raspberries on my way to the outhouse. (And then there are the wild mushrooms I gathered while walking Lucy this morning, but that wasn't even in the garden.) Especially as our garden becomes heavier on perennials, our lifestyles more closely mimic hunter-gatherers.

I guess my point is that even though backyard gardens grew out of agriculture, they can keep growing until they are sustainable and more like natural ecosystems.