Establishing a commune in the heart of the people

I was interested to see how

my mother's experience meshed with those of the people in Back from

the Land, so I gave

her my copy and quickly got a very negative reaction. "Maybe by

the 70s, the general climate was more disaffection, and just 'dropping

out,'" Mom emailed me, adding: "My own personal odyssey was...the aura

of 'peace farms' that I'd learned of thru Annie Upshure and the

Catholic Worker movement, safe places to try to work for peace."

I was interested to see how

my mother's experience meshed with those of the people in Back from

the Land, so I gave

her my copy and quickly got a very negative reaction. "Maybe by

the 70s, the general climate was more disaffection, and just 'dropping

out,'" Mom emailed me, adding: "My own personal odyssey was...the aura

of 'peace farms' that I'd learned of thru Annie Upshure and the

Catholic Worker movement, safe places to try to work for peace."

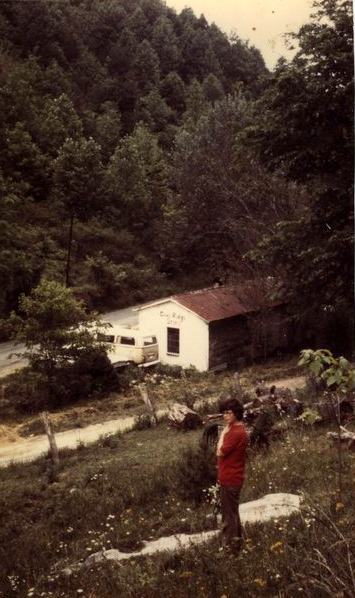

"Our actual venture was

to establish a commune 'in the heart of the people' (as in 'swim like

fish in the heart of the people')," Mom explained. Although she

wasn't part of the Vista program, my mother came south with several

people who were and she and others considered themselves "to be sort of

'independent Vistas.' We tried to live close to our neighbors,

admittedly only a few of the poorest families, actually ones who were

not farmers with their own land, but who were sharecroppers."

Mom grew up in

Massachusetts, so her first five years in southwest Virginia were all

about "putting down roots.... Because I was politically aware, I

could see my life as part of a bigger picture. And I was helped

by [my neighbors] in believing that learning how to live in the Mendota

area was viable." She added her "own twist" by working with

others on a Helping Hand Community Center, then by opening up an old

country store that served some community center functions.

"[Our neighbors] were a real

reason we were able to hang on for the ten years we did," Mom

added. "Because we were not in a commune, we were thrown on our

own resources." One of these days, I'll edit a fascinating video

interview in which Mom tells us much more about those devices, but

that's one of those back burner projects that has yet to see the light

of day.

"[Our neighbors] were a real

reason we were able to hang on for the ten years we did," Mom

added. "Because we were not in a commune, we were thrown on our

own resources." One of these days, I'll edit a fascinating video

interview in which Mom tells us much more about those devices, but

that's one of those back burner projects that has yet to see the light

of day.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

The sense of the 60's and 70's move towards communes and being close the the Earth was enveloped by a sense that a new way of relating was required in order enable individuals the feel more authentic in their lives. The movement was also embedded in the politics of the time that included anti-government, socialism, communism, revolution, and god knows drugs. It was called dropping out by friend and foe alike, when the core disposition was redefining what it meant to be family and society.

Today movements like homesteading, intentional communities, permaculture, survivalists, are derivatives of those times. The dynamics of scale and effective impact of any of these efforts ignore the wider dynamics of the scale of society as it currently exists. In this is rooted the desire to be left alone, to be allowed to live, to evolve, without those outside this experience meddling.

There is a pedagogy here that has always intrigued me. It is not just about the involvement, or the interest in these views of how to live, but the need to move others to realize the motivations for change.

It seems important to recognize that both in the Back to the Land movement of the 60s and 70s and in today's homesteading movement, individuals bring a wide range of motivations and expectations to their efforts - as this post clearly shows.

We all work within the political, cultural, economic, and environmental contexts of our times, but people involved in developing a more direct relationship with the land (if that is a broad enough umbrella to describe all these movements) may still be trying to achieve vastly different things, for themselves or for society at large, than their contemporaries. Some have ideas of "authenticity", some want to change economies, some may be searching for a different type of community, some may have religious motivations, etc.

Many people involved in homesteading today may well be informed by movements of the 60s and 70s, but what does it mean for today's efforts to be "derivative" beyond the fact that they address similar topics and are happening later? The word seems to suggest that today's movements are somehow defined or contained by what happened in the past (and especially by what we think succeeded or failed in the past).