Drying food with and without electricity

I've been having a lot of fun

drying

strawberry leather in an old car (22 cups of strawberry

leather preserved for winter feasts!), but there are clear downsides to

the method. Deanna DeLong summarized the pros and cons of several

different methods of drying as follows.

I've been having a lot of fun

drying

strawberry leather in an old car (22 cups of strawberry

leather preserved for winter feasts!), but there are clear downsides to

the method. Deanna DeLong summarized the pros and cons of several

different methods of drying as follows.

Oven

drying. You

can simply put your food on cookie sheets (or on cheese-cloth-covered

oven racks), turn the oven on very low, crack the door, and dry food

that way. But oven drying takes two to three times as long as

dehydrator drying (which means fewer nutrients and less flavor survives

the process) and you use a lot more electricity. You need to move

the food around often since the air flow isn't very regular, and you

often end up with areas that overheat and turn brittle. I think

that oven drying's primary use is as a backup to solar drying --- if

you have food nearly dry and suddenly the weather turns rainy, you can

finish it off in the oven.

Sun-drying. The simplest

dehydration method is to put your food on cookie sheets or screens in a

sunny spot, covering them with netting to keep off bugs. Although

easy, sun-drying is really only appropriate for climates with high heat

(highs in the 90s or above for extended periods), low humidity, and low

air pollution. If you can get away with it (mostly in the

southwest if you live in the U.S.), sun-drying is the cheapest method

and the UV light kills some microorganisms in your food. On the

other hand, sun-drying can take ten times as long as dehydrator drying

(which means fewer nutrients left at the end), and cloudy or rainy days

can ruin your food. Even in hot climates, sun-drying is only

appropriate for fruit, and you need to be prepared to poke at the

drying produce two or three times a day.

Sun-drying. The simplest

dehydration method is to put your food on cookie sheets or screens in a

sunny spot, covering them with netting to keep off bugs. Although

easy, sun-drying is really only appropriate for climates with high heat

(highs in the 90s or above for extended periods), low humidity, and low

air pollution. If you can get away with it (mostly in the

southwest if you live in the U.S.), sun-drying is the cheapest method

and the UV light kills some microorganisms in your food. On the

other hand, sun-drying can take ten times as long as dehydrator drying

(which means fewer nutrients left at the end), and cloudy or rainy days

can ruin your food. Even in hot climates, sun-drying is only

appropriate for fruit, and you need to be prepared to poke at the

drying produce two or three times a day.

Drying

in a warm room.

A few foods can be successfully dried in a warm room. These

include herbs and nuts in the shell. Be sure to set up a fan to

move moisture-laden air off the drying food.

Solar dehydrator. A solar

dehydrator like the

one we dream of building can elevate air temperature by 20 to 30

degrees Fahrenheit, so you can get away with drying food in more

temperate climates, even if you have high humidity. You're

still at the mercy of the weather and food must be rotated, but solar

dehydrators will dry food faster than sun-drying, so the food is more

nutritious.

Solar dehydrator. A solar

dehydrator like the

one we dream of building can elevate air temperature by 20 to 30

degrees Fahrenheit, so you can get away with drying food in more

temperate climates, even if you have high humidity. You're

still at the mercy of the weather and food must be rotated, but solar

dehydrators will dry food faster than sun-drying, so the food is more

nutritious.

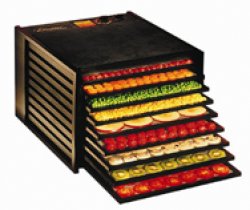

Electric

dehydrator.

A good electric dehydrator has a thermostatically controlled heating

unit and a fan, so food is dried as fast as possible (meaning maximum

flavor and nutrients.) Top of the line units heat very evenly,

too, so they're set-it-and-forget-it, and  many even come with a

timer. After doing the math on how much it would cost me to buy

enough cookie sheets to dry our excess fruit in our very variable

climate using the sun, I decided to go ahead and buy an electric

dehydrator. More on the model we chose once it arrives and we

give it a test run.

many even come with a

timer. After doing the math on how much it would cost me to buy

enough cookie sheets to dry our excess fruit in our very variable

climate using the sun, I decided to go ahead and buy an electric

dehydrator. More on the model we chose once it arrives and we

give it a test run.

Solar/electric

hybrid dehydrator.

You can get the best of both worlds (low energy usage and fast,

nutritious food) by building a solar/electric hybrid. The solar

collector heats the food on sunny days, while the thermostatically

controlled heating unit kicks on when it's cloudy and at night. A

fan keeps air flow more uniform. I dream of turning our electric

dehydrator into a hybrid unit, but Mark wants to spend a bit more time

learning how a standalone solar dehydator works first.

I think that the path I

took --- dabbling in solar dehydrating in an old car and with the oven

--- is a good beginning to see if you like the flavor of dried

food. But if you decide to make dehydration one of your main food

storage methods, you'll probably want to build a high tech solar

dehydrator or buy one of the best consumer grade electric dehydrators

(or maybe do a little of both.)

| This post is part of our How to Dry Foods lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Freeze drying can be done with or without vacuum.