Does growing your own food matter?

Roland sent me a link to an

intriguing article in the New York Times called "Math

Lessons for Locavores."

The author argues that locavores need to take a harder look at the

facts and realize that the distance food travels before it reaches

their plates accounts for only 14% of the total energy costs of their

eating habits. While I like Stephen Budiansky's focus on numbers,

the author's conclusion doesn't make as much sense to me. He ends

his article by saying, in essence, that our current agricultural system

is just peachy. I couldn't agree less.

Roland sent me a link to an

intriguing article in the New York Times called "Math

Lessons for Locavores."

The author argues that locavores need to take a harder look at the

facts and realize that the distance food travels before it reaches

their plates accounts for only 14% of the total energy costs of their

eating habits. While I like Stephen Budiansky's focus on numbers,

the author's conclusion doesn't make as much sense to me. He ends

his article by saying, in essence, that our current agricultural system

is just peachy. I couldn't agree less.

Here's

a quick example to help you see one small reason why I think that even

mainstream organic farming is fatally flawed. While touring Abingdon

Organics, I was

shocked to hear that Anthony tosses 200 pounds of culled tomatoes and

peppers in his compost pile every week. Mark and I once attended

a few meetings as potential growers for Anthony's organic gardening

marketing association, and I can personally attest that those culls

aren't nearly as bad as the tomato I

chewed Mark out for throwing to the chickens a few weeks ago.

Chances are, the culled vegetables had a slightly odd shape, were too

big or too small, or had a minute blemish. A hundred years ago,

those culls would have been known as "food", or, at the worst, would

have fed pigs or chickens that would quickly become human food.

Here's

a quick example to help you see one small reason why I think that even

mainstream organic farming is fatally flawed. While touring Abingdon

Organics, I was

shocked to hear that Anthony tosses 200 pounds of culled tomatoes and

peppers in his compost pile every week. Mark and I once attended

a few meetings as potential growers for Anthony's organic gardening

marketing association, and I can personally attest that those culls

aren't nearly as bad as the tomato I

chewed Mark out for throwing to the chickens a few weeks ago.

Chances are, the culled vegetables had a slightly odd shape, were too

big or too small, or had a minute blemish. A hundred years ago,

those culls would have been known as "food", or, at the worst, would

have fed pigs or chickens that would quickly become human food.

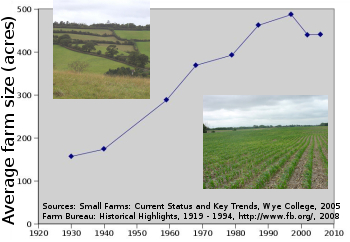

In

my opinion, the problem with mainstream agriculture is not the miles

food travels to get to our plates; the problem is sheer size.

Over the last hundred years, farmers

have been forced to grow food on larger and larger acreages or go out

of business, with

the result that they simply cannot keep the farm ecosystem

balanced. Pollution from concentrated animal feeding operations

is yet another example. Just as today's culls used to turn into

yesteryear's soups, today's problem manure used to be yesteryear's

black gold.

In

my opinion, the problem with mainstream agriculture is not the miles

food travels to get to our plates; the problem is sheer size.

Over the last hundred years, farmers

have been forced to grow food on larger and larger acreages or go out

of business, with

the result that they simply cannot keep the farm ecosystem

balanced. Pollution from concentrated animal feeding operations

is yet another example. Just as today's culls used to turn into

yesteryear's soups, today's problem manure used to be yesteryear's

black gold.

Although

the average eater can't shut down factory farms or change the policies

that make the typical American farm a 400 acre monoculture, we can take

simple actions that will start to change the system. Forget the

greenwashing labels on the food from the grocery store and start

thinking about your own growing, cooking, and refrigerating

habits. In "Math Lessons for Locavores", Stephen Budiansky wrote

that 32% of food energy costs come from refrigerating and cooking that

food at home. If you grow your own vegetables, you won't need to

run one of those huge refrigerators that grace the modern home --- you

just take the food out of the garden, cook gently, and throw it on your

plate, putting the leftovers in a smaller, energy-efficient

model. A rocket stove is on our winter project list to further

lower our energy footprint.

Although

the average eater can't shut down factory farms or change the policies

that make the typical American farm a 400 acre monoculture, we can take

simple actions that will start to change the system. Forget the

greenwashing labels on the food from the grocery store and start

thinking about your own growing, cooking, and refrigerating

habits. In "Math Lessons for Locavores", Stephen Budiansky wrote

that 32% of food energy costs come from refrigerating and cooking that

food at home. If you grow your own vegetables, you won't need to

run one of those huge refrigerators that grace the modern home --- you

just take the food out of the garden, cook gently, and throw it on your

plate, putting the leftovers in a smaller, energy-efficient

model. A rocket stove is on our winter project list to further

lower our energy footprint.

Truthfully,

though, I think that even those steps are a bit cosmetic. The

real way to make your eating habits an asset to the planet rather than

an oozing sore is to grow your own food on a small enough scale that

you can put all of the "waste" back into the farm to feed the

soil. Although you don't hear it bandied about much, I see no

reason why adding compost to your soil and growing cover crops wouldn't

count as carbon sequestration --- after all, humus can take up to a

thousand years to decompose. Add in some livestock to make the

ecosystem more complete, and you've got a simple permaculture farm that

feeds butterflies and birds as well as humans.

Truthfully,

though, I think that even those steps are a bit cosmetic. The

real way to make your eating habits an asset to the planet rather than

an oozing sore is to grow your own food on a small enough scale that

you can put all of the "waste" back into the farm to feed the

soil. Although you don't hear it bandied about much, I see no

reason why adding compost to your soil and growing cover crops wouldn't

count as carbon sequestration --- after all, humus can take up to a

thousand years to decompose. Add in some livestock to make the

ecosystem more complete, and you've got a simple permaculture farm that

feeds butterflies and birds as well as humans.

If

growing your own food is so great, why don't we see more people jumping

on the bandwagon? Well, there's very little profit in it, for one

thing, so marketers feel no need to spread the word. Growing your

own food also takes time and effort, and we're all inherently lazy

people who would far rather think we were changing the world by paying

double for a zucchini marked "organic" than putting down a kill mulch

in the backyard and getting to work. To top our reasons off,

everyone knows that the average American is far too busy to commit 15

hours a week to growing crops, even though we easily spend that much

time in front of a TV. And, heck, what can one person's actions

do? How quickly we forget that during World War II, little

backyard victory gardens

produced 40% of Americans' food.

If

growing your own food is so great, why don't we see more people jumping

on the bandwagon? Well, there's very little profit in it, for one

thing, so marketers feel no need to spread the word. Growing your

own food also takes time and effort, and we're all inherently lazy

people who would far rather think we were changing the world by paying

double for a zucchini marked "organic" than putting down a kill mulch

in the backyard and getting to work. To top our reasons off,

everyone knows that the average American is far too busy to commit 15

hours a week to growing crops, even though we easily spend that much

time in front of a TV. And, heck, what can one person's actions

do? How quickly we forget that during World War II, little

backyard victory gardens

produced 40% of Americans' food.

I'll step down off my

soapbox now. Thanks for reading a post that got way too

long! Feel free to tear my reasoning apart in the comments.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Lisa --- we probably make gardening look harder than it really is. We're always trying out so many different things that we do fill up about half of our days with farm work, but the actual time spent growing all of the vegetables and some of the fruits that two people eat takes up only about 10 hours per week. That figure includes growing and freezing enough food to take us all the way through the winter, so if you wanted to start out by just growing enough fresh food for your family during the main growing season, I'll bet you could put in as little as 1 hour per day! A commitment that small could probably fit much more easily into your schedule, I suspect.

AB --- Taste is a very excellent point, as is the nutrition that the taste represents. I wasn't really going there in this post because it already got way, way too long, but there are clearly benefits to local eating that don't get touched on when you merely look at the energy consumed to get the food from farm to plate. As both you and Lisa pointed out, supporting small farmers is also another bonus of eating locally --- not only are you putting money into the local economy, but you're also voting with your wallet to keep farm sizes small and the environment more pristine.

Actually, wrt regfigerator efficiency bigger is better. Suppose you have a refrigerator that is a cube (all edges the same length) for the sake of easy calculation. Consider that for a given temperature difference between inside and outside and a given insulation material and thickness heat infiltration is lineairly dependant on surface area (which scales with the square of the characteristic length), while storage volume scales with the characteristic length cubed.

So if you make the edge twice as big, the surface area (and therefore energy usage) grows by a factor of four, but the volume grows by a factor of eight! So the cooling energy needed per unit of volume is cut in half.