Cover crop questions

I'm

intrigued by the primary use of cover crops to

enrich the soil without tilling. I'm also interested in incorporating a

no till system.

I'm

intrigued by the primary use of cover crops to

enrich the soil without tilling. I'm also interested in incorporating a

no till system.

How

would you convert a plot of grassy weeds into garden space? I would use

a hoe and clear all of the weeds out, cart them away and compost them

if I had a heated pile going. Then I would sow the seed of an annual

cover crop into the heavy clay soil I have (not sure what cover crop

I'd use. Maybe annual rye grass or oats I've read is good) in the

spring. I live in the deep south so I don't know if winter killing

would be optional. So I'd probably use a scythe or a mower to cut them

in place before fall and then leave them on the ground to rot. I would

then cover the rye grass with compost and sow fall vegetables in the

compost. That would be my ideal way to begin my bed. I'm curious if

this would work.

Also

how important is it that the cover crops be annuals? I've read of using

clover but I know this is a perennial but I'm not sure how it grows.

Does it just reseed itself or is it just not winter killed? Also I've

read of growing vegetables with clover as a living mulch. What is your

opinion of this? I imagine the clover would compete with the crops and

there wouldn't be significant growth in the vegetables.

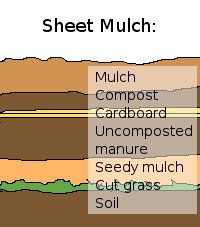

Thanks for the great

questions, Jalen! My favorite way to convert a grassy area into

garden without tilling is to use a kill mulch (aka a sheet

mulch.) You can read the long version in the May

volume of my ebook series (which I'm emailing you a

copy of), but the short version is that you lay down a few sheets of

damp corrugated cardboard to kill the grass, with compost above and/or

below, then top the whole thing off with mulch. If you've got

time to leave the kill mulch on for a summer before planting, you'll

then be able to grow anything you want. If you're going to plant

into your kill mulch immediately, I recommend putting a good layer of

compost on top of the cardboard and seeding only shallow-rooted crops

your first year.

While your method would work

(especially if you used a shovel instead of a hoe), it would really

amount to tilling and you'd lose a lot of the organic matter right at

the soil surface. Granted, your cover crop would replace some of

that. An annual cover crop that works in the summer is buckwheat, which can easily be killed

using a mower, weed eater, or just by yanking the plants out of the

ground and laying them on the soil surface once they're in full

bloom. (Buckwheat's not a big fan of clay, though.) A

problem you might run into if you used a grain instead (generally

planted in the fall) is that the more woody plant matter would suck

nitrogen out of the soil as it decomposed, so you might end up with

hungry vegetables unless you added a lot of compost. I like to

rake oat leaves back in the spring, add my compost and plant my seeds,

and then bring the oat mulch back up around the young plants as they

get big enough to handle the occasional oat straw leaf blown out of

place.

While your method would work

(especially if you used a shovel instead of a hoe), it would really

amount to tilling and you'd lose a lot of the organic matter right at

the soil surface. Granted, your cover crop would replace some of

that. An annual cover crop that works in the summer is buckwheat, which can easily be killed

using a mower, weed eater, or just by yanking the plants out of the

ground and laying them on the soil surface once they're in full

bloom. (Buckwheat's not a big fan of clay, though.) A

problem you might run into if you used a grain instead (generally

planted in the fall) is that the more woody plant matter would suck

nitrogen out of the soil as it decomposed, so you might end up with

hungry vegetables unless you added a lot of compost. I like to

rake oat leaves back in the spring, add my compost and plant my seeds,

and then bring the oat mulch back up around the young plants as they

get big enough to handle the occasional oat straw leaf blown out of

place.

To answer your question

about annual vs. perennial cover crops --- annuals have a big advantage

in no-till systems in that you can often find a way to kill

the plants without impacting the soil in any way. Perennial cover crops

are generally tilled into the ground (although you can also lay down a

kill mulch over top of them after mowing the cover crops close to the

soil.)

There are several types of

clover, some of which are annuals and some of which are

perennials. The primary annual clover is crimson clover, which is generally planted

in the fall in the south, overwinters, and then is killed in late

spring or early summer as it begins to bloom. My father (in South

Carolina) has let his crimson clover go all the way to seed, at which

point it dies back naturally, then he plants into the mostly bare soil

and lets the clover come back from seed in the fall. He does till

his garden every year, though, so I'm not positive this system would

work with no-till. (In my own garden, I find that crimson clover

doesn't keep back weeds very well over the winter. In general,

grain cover crops are much better at suppressing weeds and adding

organic matter to the soil while legume cover crops are best at

providing a quick dose of nitrogen.)

There are several types of

clover, some of which are annuals and some of which are

perennials. The primary annual clover is crimson clover, which is generally planted

in the fall in the south, overwinters, and then is killed in late

spring or early summer as it begins to bloom. My father (in South

Carolina) has let his crimson clover go all the way to seed, at which

point it dies back naturally, then he plants into the mostly bare soil

and lets the clover come back from seed in the fall. He does till

his garden every year, though, so I'm not positive this system would

work with no-till. (In my own garden, I find that crimson clover

doesn't keep back weeds very well over the winter. In general,

grain cover crops are much better at suppressing weeds and adding

organic matter to the soil while legume cover crops are best at

providing a quick dose of nitrogen.)

I believe Steve

Solomon is the one

who wrote about growing white clover between the garden rows as a

living mulch. White clover is a perennial, so it will keep

plugging along unless you rip it out by the roots. Solomon's

method involved mowing the clover often enough so that it  didn't

compete with the vegetables, allowing the high nitrogen clover leaves

to mulch and feed the garden, along with the high-nitrogen root nodules

that are shed by the clover when it is mowed. I didn't mean to

follow Solomon's lead, but in one of my garden areas, white clover

naturally sprang up in the mowed aisles between my beds, so I gave a

variation on his method a shot. In my garden, at least, the

living mulch system is problematic since my aisle clover tries to run

into the vegetables' space at every opportunity and I spend a lot of

time ripping it out.

didn't

compete with the vegetables, allowing the high nitrogen clover leaves

to mulch and feed the garden, along with the high-nitrogen root nodules

that are shed by the clover when it is mowed. I didn't mean to

follow Solomon's lead, but in one of my garden areas, white clover

naturally sprang up in the mowed aisles between my beds, so I gave a

variation on his method a shot. In my garden, at least, the

living mulch system is problematic since my aisle clover tries to run

into the vegetables' space at every opportunity and I spend a lot of

time ripping it out.

You mentioned in your

email that you are seventeen and that your parents aren't into growing

vegetables --- I hope you're able to find space to give some of these

ideas a shot. The best way to learn about gardening is to get

your hands dirty and try things out. You'll soon discover what

does and doesn't work (and will have fun in the process.) Good

luck!

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Thank you for answering my questions in such detail. For some reason i didn't even think about sheet mulching. You were right about: "you'd lose a lot of the organic matter right at the soil surface." I also did not consider that.

I was unaware crimson clover was an annual. I've actually read it’s a perennial and an annual. I actually purchased arrowhead clover at a feed store because they were out of crimson. I sowed this directly on top of a small space my parents have allowed for "experimentation". I had no compost available and i actually just weeded it with a hoe and sowed the clover. It sprouted quite well in the clay and is growing well. Yet I noticed it takes approx. like 150 days for it to reach maturity unlike buckwheat which grows very rapidly. Thats the only problem that sticks out to me. I was hoping to find a type of grain that grows deep tap roots to break up the clay as well. But I haven’t done my research yet on that.

Also I will check out that email you sent me when I get out of this school building. Thank you again.

Jalen