archives for 03/2014

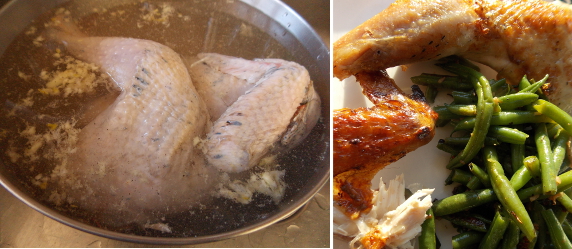

One of the few

store-bought foods that Mark and I still consider a guilty pleasure is

the occasional rotisserie chicken. That makes me want to learn to

cook a chicken as succulently delicious so I can make an equally tasty

(but more nutritious) version at home. My first experiment

involved brining one of our homegrown chickens with pepper and garlic added to the salted water, then roasting

the bird while basting with butter. The result was tasty,

but the leg meat was still a bit tougher than I would have liked.

I'm curious to hear from

our readers who also grow heirloom chickens for meat. Do you have a

favorite way of turning the meat tender and succulent? Or perhaps

this is a losing battle and you can only get that kind of mouth-feel if

you raise Cornish Cross, who grow so fast they're still very young when

slaughtered? I'd love to hear your feedback in the comments

section!

This 1955 Survival film was

made by the US Navy to educate pilots on how

to live off the land in north temperate regions but has some

considerable entertainment value to the modern day homesteader.

I enjoyed the drawings of

animal traps and the narrator's casual tone, even though he seems to

think turtles are amphibians.

The section on edible insects

taught me that caterpillars are not good to eat but grubs are often the

safer bet.

October through February

are our primary visiting seasons due to farm constraints the rest of the

year. Of these months, the first and the last are the best for

trips because weather is mild enough that the chickens don't need extra

care and the house can survive without a wood fire, but the garden isn't

nipping at my heels. Soon, our first chicks will be hatching and

I'll want to be on hand in case they have trouble for the next couple of

months, and after that the weeds will be growing a mile a minute, then

the garden produce will be begging to be preserved. I rarely feel

called to leave the farm at any season, but soon even those urges will

be stilled.

Which is all a long way of explaining why we slipped away this weekend to visit my father and attend the South Carolina Organic Growing Conference.

More photos and tidbits from the trip in later posts --- today I'm just

sharing a photo of Mom's visit last weekend when Huckleberry clearly

ruled the roost.

If you want to go to a

conference 45 minutes from your father's house and want to squeeze in a

visit at the same time, do you attend the conference first and visit

afterwards, or do you have family time right off the bat? Mark's

gut said the latter, and I think he was right, since I wanted to see

Daddy more than I wanted to learn at the conference...and some weeks I

can't manage even one night away from home. After a wonderful

visit on Friday, I managed to net two whole hours of sleep, and that

only came once I gave up on the bed in the guest room and on the quiet

and comfortable couch and went to squeeze myself into the back seat of

the car. (Yes, I am the world's weirdest sleeper and really like

small spaces. I should have brought my tent.)

Anyway, that's all a long way of explaining why --- even though Mark and I were itching to hear Tradd's

newest talks and to check out the South Carolina Organic Growing

Conference --- we only managed to enjoy a delicious lunch there before

heading home. On two hours of sleep, even pastured pigs, medicinal

mushrooms, and biointegrated homesteads didn't sound as lovely as

returning to the peace and quiet of our own farm.

Anyway, that's all a long way of explaining why --- even though Mark and I were itching to hear Tradd's

newest talks and to check out the South Carolina Organic Growing

Conference --- we only managed to enjoy a delicious lunch there before

heading home. On two hours of sleep, even pastured pigs, medicinal

mushrooms, and biointegrated homesteads didn't sound as lovely as

returning to the peace and quiet of our own farm.

I did get one of the

nicest February tomato plants I've ever seen out of the weekend, though,

plus some cuttings and a rooted sprout from Daddy's Brown Turkey

fig. That brings us up to five fig varieties we're trialling for cold hardiness here at the edge of their range. More on what I'm doing with my new figs in a later post.

A popular chicken hang out

during snow days is under our old camper.

Lucy likes this same spot on

hot summer days for the shade and cool ground.

After quite a bit of experimentation,

last year I settled on a very simple (but effective) method of

propagating figs. I take hardwood cuttings and sink them about

eight inches into damp stump dirt

in a pot, put the pot on a heating pad, and ignore it for a few weeks

until I need the heating pad for something else. I water

occasionally during those heating-pad weeks and during the subsequent

weeks, keeping the soil at the moisture level appropriate for

seed-starting (or just a hair drier), and put the pots in a sunny spot

once the leaves begin to push out of the buds. By the end of the

summer, the cuttings are extraordinarily well rooted and are ready to go

into the ground.

After quite a bit of experimentation,

last year I settled on a very simple (but effective) method of

propagating figs. I take hardwood cuttings and sink them about

eight inches into damp stump dirt

in a pot, put the pot on a heating pad, and ignore it for a few weeks

until I need the heating pad for something else. I water

occasionally during those heating-pad weeks and during the subsequent

weeks, keeping the soil at the moisture level appropriate for

seed-starting (or just a hair drier), and put the pots in a sunny spot

once the leaves begin to push out of the buds. By the end of the

summer, the cuttings are extraordinarily well rooted and are ready to go

into the ground.

I

treated the Brown Turkey cuttings from Daddy to last year's

methodology, and also potted up the rooted shoot we teased away from the

base of his mature fig bush. The latter will go into the ground

soon after our frost-free date, and I'm thinking of putting it on the

west side of our wood-stove alcove so the fig will enjoy lots of winter

sun and heat while helping shield the trailer from summer sun.

I'll probably keep one of the rooted cuttings as well and then will give

the rest away to blog readers or local friends, so stay tuned for

future giveaways.

I

treated the Brown Turkey cuttings from Daddy to last year's

methodology, and also potted up the rooted shoot we teased away from the

base of his mature fig bush. The latter will go into the ground

soon after our frost-free date, and I'm thinking of putting it on the

west side of our wood-stove alcove so the fig will enjoy lots of winter

sun and heat while helping shield the trailer from summer sun.

I'll probably keep one of the rooted cuttings as well and then will give

the rest away to blog readers or local friends, so stay tuned for

future giveaways.

This Snap On extra long ratchet driver made

these hard to reach jobs easier.

It's one of the few tools

I've held onto since my copier repair days.

I'm always of two minds

about the first spring flowers. On the one hand, I really, really

want to see them, not just for myself, but for my hungry bees. But

on the other hand, I know that early blooms on the fruit trees often

mean no harvest that year due to late freezes. So I decided to

poke back through the blog to determine when our peaches and crocuses

have bloomed in past years, and how that relates to the subsequent peach

harvest:

| Year |

First crocus bloom |

Peaches at first pink stage |

Peaches harvested? |

| 2013 |

1/31 |

4/5 |

Yes |

| 2012 |

2/3 |

3/15 |

No |

| 2011 |

2/20 |

3/22 |

Yes |

| 2010 |

3/7 |

4/3 |

Yes |

| 2009 |

2/28 |

3/23 |

No |

The

first thing I noticed --- late peach blooms do seem to be correlated to

an actual peach harvest that year. But do early crocus blooms

mean no peach harvest? Nope. In fact, the date of the first

crocus blooms seems to have very little bearing on when the peach

flowers open, suggesting that the two plants are using different cues

to decide on the proper time to pop open their flowers. (Last

year's crocus blooms might have been a bit of an outlier, though,

because I had transplanted the bulbs in late winter to a new location.)

The

first thing I noticed --- late peach blooms do seem to be correlated to

an actual peach harvest that year. But do early crocus blooms

mean no peach harvest? Nope. In fact, the date of the first

crocus blooms seems to have very little bearing on when the peach

flowers open, suggesting that the two plants are using different cues

to decide on the proper time to pop open their flowers. (Last

year's crocus blooms might have been a bit of an outlier, though,

because I had transplanted the bulbs in late winter to a new location.)

This post is all a long

and geeky way of saying --- okay, crocuses, open up those buds!

And, peaches, stay sound asleep as long as you can. Because, of

course my plants listen to my wishes, right? (Maybe I should hedge

my bets by dumping the ice from my maple sap concentration campaign around the bases of our fruit trees.)

We upgraded our grape

shade trellis today.

Thanks to one of our constant

readers Brian we realized the 2x4's we planned to put up would block a

good deal of Winter sun.

It's two loops of 10 gauge

galvanized trellis wire that uses a couple of heavy duty turnbuckles to

increase the tension.

As you may have noticed,

I've been running a bit of an ongoing series here with answers to

questions new chicken-keepers might have. Previous posts included how to hatch homegrown chicks and how to choose the best chicken breeds for homesteaders.

Today I want to touch on a topic that's not so photogenic, but that

needs to be considered by anyone who wants to get into chickens --- how

to protect those delicious morsels from the wild animals who'd love

nothing more than to eat them up.

Baby chicks are most likely to be eaten by rats and snakes, but adult hens tend to succumb to dogs, hawks, raccoons, opossums, and similar predators.

Your first line of defense against predators is to protect your flock

when they're most vulnerable --- at night. A solid chicken coop is

optimal, and if your predator pressure is high you'll want to shut the

birds in each evening (or to invest in an automatic chicken door

to do the job for you). Raccoons, especially, can reach right

through small holes, so be sure your birds' roost is far enough away

from gaps so that a predator can't rip their heads off without even

entering the  hen

house. To be truly predator proof, the coop will also need to

have a solid base that extends for several inches into the soil to

prevent diggers from entering the coop. Finally, even though I

love giving scraps to chickens, I'm starting to lean away from putting

those kitchen scraps in the coop since the scent attracts predators who

stick around to eat my birds.

hen

house. To be truly predator proof, the coop will also need to

have a solid base that extends for several inches into the soil to

prevent diggers from entering the coop. Finally, even though I

love giving scraps to chickens, I'm starting to lean away from putting

those kitchen scraps in the coop since the scent attracts predators who

stick around to eat my birds.

What if your chickens are

getting picked off in the daytime instead? If you have a small

run (which you shouldn't), you can beef up the walls just like you did

the coop, then can string fishing line over the top in a woven pattern

to keep out hawks and owls. But if you prefer giving your birds

larger pastures, or even letting them free range, it's going to be

nearly impossible to keep predators out of their daytime living

area. Instead, I recommend adding a rooster to your flock, since

he'll sound the alarm and do his best to fight off any invader during

daytime hours. A good dog (trained to protect, rather than eat, chickens)

is the second line of defense --- our dog comes running as soon as she

hears our rooster's alarm call, and she has managed to chase away a hawk

that had pinned a hen three times over the past winter.

Chickens

are pretty alert to predators during the daytime, with hawks being

their primary downfall. After a rooster and a dog, I have two more

lines of defense against raptors. First, I make sure that our

chickens roam in areas with lots of bushes and other things to hide

under. Hens often see a hawk coming as the raptor dives down to

dine, so if they have something to scurry beneath, the chickens might be

able to evade capture. Second, I raise dark-colored chickens,

since I've learned the hard way with multiple breeds over multiple years

that letting white chickens free range is like putting up a flashing

neon sign: "Chicken take-out, now hot!"

Chickens

are pretty alert to predators during the daytime, with hawks being

their primary downfall. After a rooster and a dog, I have two more

lines of defense against raptors. First, I make sure that our

chickens roam in areas with lots of bushes and other things to hide

under. Hens often see a hawk coming as the raptor dives down to

dine, so if they have something to scurry beneath, the chickens might be

able to evade capture. Second, I raise dark-colored chickens,

since I've learned the hard way with multiple breeds over multiple years

that letting white chickens free range is like putting up a flashing

neon sign: "Chicken take-out, now hot!"

I'd be curious to hear

from others who have dealt with their own predator problems. Which

predators are the most likely to eat your chickens? What do you

do to protect the flock?

And for those of you in the planning stages of starting your own chicken operation, be sure to check out our chicken waterers, which keep you from having to handle manure and keep your birds from having to drink it.

What would I do differently

when installing another heavy

duty shade trellis?

Use fresh trellis wire. We

used some recycled wire on the first loop and straightening out the

kinks used up most of the tension in the turnbuckle.

The second loop was from a

fresh roll and looks a lot tighter.

Last year at this time, we were chowing down on kale and lettuce leaves that survived the winter under quick hoops

and started rebounding as the weather warmed up. Not so in

2014. I was able to find a handful of brussels sprouts that had

been protected under the mulch for dinner Wednesday, but otherwise it's a

waiting game right now. The new lettuce I planted a few weeks ago

has sprouted and some of the kale plants survived and are sending out

new leaves, both of which we'll be eating in a few weeks.

Last year at this time, we were chowing down on kale and lettuce leaves that survived the winter under quick hoops

and started rebounding as the weather warmed up. Not so in

2014. I was able to find a handful of brussels sprouts that had

been protected under the mulch for dinner Wednesday, but otherwise it's a

waiting game right now. The new lettuce I planted a few weeks ago

has sprouted and some of the kale plants survived and are sending out

new leaves, both of which we'll be eating in a few weeks.

In the meantime, Mark is pouting because we're down to butternut squash,

carrots, sweet potatoes, and frozen green beans from last year, and

both of us are used to a more rounded vegetable diet. I'd rather

wait and eat real food than expand the selection out with grocery store

offerings, though.

The

positive side of the cold winter is that it helped me get a more solid

handle on the cold hardiness of various greens. Last winter, Fordhook Giant Swiss chard

survived the winter with no protection, so I thought the Swiss chard

might be just as hardy as our kale. Not so. Swiss chard I

protected with quick hoops this winter completely perished, along with

the Laciniato kale, but my troopers (Red Russian and Dwarf Siberian kale) survived the subzero temperatures under their quick hoops.

The

positive side of the cold winter is that it helped me get a more solid

handle on the cold hardiness of various greens. Last winter, Fordhook Giant Swiss chard

survived the winter with no protection, so I thought the Swiss chard

might be just as hardy as our kale. Not so. Swiss chard I

protected with quick hoops this winter completely perished, along with

the Laciniato kale, but my troopers (Red Russian and Dwarf Siberian kale) survived the subzero temperatures under their quick hoops.

I used to think of Red

Russian as the more delicate of my two dependable kale varieties, but it

turns out that the smaller variety did better during this excessively

cold winter. Those of you in the true north should take note and

plant accordingly, although I'll admit that if we started having winters

like this one more regularly, I'd follow Eliot Coleman's advice and erect a high tunnel over my quick hoops.

We've still been having an

issue with rats in the chicken coop.

I sent one to an early grave

thanks to some help from a box of Rat Shot.

You can find a box of 20 for

around 8 dollars. The small pellets spread out making it easy to hit a

moving rodent while at the same time any extra shot ends up bouncing

off nearby structures.

Five years ago, Strider turned up in our barn,

sick and in need of a home. Since then, we've managed just fine

with two cats --- Strider does all the hard work around the farm and

Huckleberry lets us spoil him. But Thursday afternoon, the cat

balance got out of whack.

Another plaintive meow

from the barn turned up this little critter, who is still too scared of

me to let me check its sex. The barn cat looks pretty healthy, but

was starving and quickly downed nearly a quart of dry cat food over the

first 24 hours before starting to slow down to a more normal eating

pace.

I'm not quite sure what

to make of the feline. It meows plaintively at me, begging for

something even when there's still food in its dish, but it's too scared

to come closer than three or four feet away from a human, and that only

when I sit down and look in the other direction.

Two cats in the house is

really more than I can handle, especially when they both want attention

at once. (Mark's more of a dog person.) So Mark and I are

agreed that this little feline wouldn't fit in. But I'm not sure

if I can catch it to give it away, so I'm a little stuck by the cat in

the barn. Does anyone local want a cat in need of serious TLC?

How did the new seed

starting shelf turn out?

Not only does the worn barn

wood look nice but the height is just right to slide the indoor

chick brooder under which is about to be booted up any day now.

I've always wanted to be able to test the pH

of my soil at home, since that's one soil quality I need to manage

carefully, especially around blueberries. However, the cheap pH

meter I picked up at a big-box store several years ago wasn't even worth

the few bucks I paid for it --- I could never get the device to read

anything when I flipped it to pH. So when Joey got me a fancy pH

meter at an auction, I was thrilled!

I've always wanted to be able to test the pH

of my soil at home, since that's one soil quality I need to manage

carefully, especially around blueberries. However, the cheap pH

meter I picked up at a big-box store several years ago wasn't even worth

the few bucks I paid for it --- I could never get the device to read

anything when I flipped it to pH. So when Joey got me a fancy pH

meter at an auction, I was thrilled!

The Kelway Soil Tester

certainly feels more impressive than the previous meter I'd been using,

but I'm not really sure I trust its results. In a few spots, the

Kelway Soil Tester read close enough to what my soil reports said that I

figured it was on track --- 6.8 in the blueberries where my 2012 soil

report said 6.5 (and where I wish the pH was much lower) and 6.2 in the

subsoil of the forest garden aisles where my soil report said 6.3.

But when I stuck the tester in a pile of leached wood ashes that have

been sitting out in the weather for a month or so, the first test read

5.6. Only after the day warmed up a bit more did that test come

back as 7.4, closer to the alkaline level I would expect from wood

ashes.

That

got me wondering if temperature could play a role in pH testing. I

know that moist soil is important for getting a meter like this to

read, but lack of water isn't anything our soil suffers from at the

moment. On the other hand, our ground is half-frozen in spots,

despite a sunny week. Does anyone understand the chemistry/physics

of pH testers enough to know whether I need to wait and test when the

ground is warm? Anything else that might make a meter think wood

ashes are acidic instead of alkaline?

That

got me wondering if temperature could play a role in pH testing. I

know that moist soil is important for getting a meter like this to

read, but lack of water isn't anything our soil suffers from at the

moment. On the other hand, our ground is half-frozen in spots,

despite a sunny week. Does anyone understand the chemistry/physics

of pH testers enough to know whether I need to wait and test when the

ground is warm? Anything else that might make a meter think wood

ashes are acidic instead of alkaline?

Jake's comment on my post

about 22

caliber pest control got me thinking.

Our Phoenix Arms 22 caliber pistol is called a

Long Rifle which I'm guessing means the barrel is rifled to improve

accuracy.

I stood 7 feet away and shot

a cardboard box that showed a pattern about 12 inches wide. What was

weird is right after I did that a rat scurried out of the weeds with

Lucy standing by to see what we were doing. Anna yelled "Get it Lucy!"

and Lucy caught it and crunched it within a few seconds. The term "Good

Girl" is a vast understatement today.

"This year I shared my seed order with a friend to bring the price down. I

never plant 25 of the same plant. I am curious how much you spent of

seeds this year. Also I am curious how many plants of what you are

planning."

"This year I shared my seed order with a friend to bring the price down. I

never plant 25 of the same plant. I am curious how much you spent of

seeds this year. Also I am curious how many plants of what you are

planning."

Even though it's a little

cheaper to buy all of our seeds at once, I actually plan on two orders

per year --- one in the winter for the main season and one in early

summer for the fall and winter garden. This year, I spent $86 on

the spring order and I spent $27 last summer on the fall order.

Keep in mind that I do buy from a relatively expensive company

(Johnny's) and I buy big packages of many seeds since we grow all of our

own vegetables and since I plant heavily in cold soil instead of

starting many seeds inside. On the other side of the equation, I

do save a lot of our own seeds

and I am sometimes able to eke out last year's packet for another year

even for types of vegetable seeds we don't save. Finally, this

calculation doesn't include cover crop seeds, which probably come to another $25 to $50 per year.

To answer your second

question --- I plan our garden by area, not by number of plants.

For example, I'll put in 8 beds of broccoli this spring and the same

amount again in the fall. Each bed is roughly 15 to 20 square

feet, and I plant using a high-density system, so that would be about 80

broccoli plants for the spring planting and another 80 plants for

fall. As you can see in the table below, since I start most of our

spring broccoli plants outside under quick hoops where germination

isn't as perfect as inside on a heating pad, I went ahead and bought

1,000 broccoli seeds this year so I'd be sure to have plenty for both

spring and fall plantings. My rule of thumb is to have at least

two or three times as many seeds as I need so I can plant heavily and

can replant if the first set doesn't come up, gets scratched up by

Huckleberry, or gets killed by a freak weather event. It's always

cheaper to buy the next size up than to rush in an extra seed order and

pay an extra round of shipping for one package of seeds.

| Crop |

Spring/Summer Beds |

Fall Beds |

Seeds ordered |

| Arugula |

1 |

Saved |

|

| Basil |

1 |

Packet |

|

| Beans, Green |

5 (Succession planted) |

Saved |

|

| Beans, Mung |

2 |

Saved |

|

| Broccoli |

8 |

8 |

1,000 seeds |

| Cabbage |

4 |

2 |

1,000 seeds |

| Brussels Sprouts |

8 |

(Will order in fall) |

|

| Carrots |

2 |

6 |

5,000 seeds |

| Corn, Sweet |

17 (Succession planted) |

1,000 seeds |

|

| Cucumbers |

6 (Succession planted) |

Saved/leftover from last year |

|

| Garlic |

13 |

Saved |

|

| Kale |

12 (Succession planted) |

Saved |

|

| Lettuce |

4 (Succession planted) |

10 (Succession planted) |

1/4 pound (I plant very heavily so we can harvest lots of baby leaves) |

| Mustard |

4 |

Leftover from last year |

|

| Okra |

2 |

Saved |

|

| Onions |

10 (These are bulbing onions from seed. In addition, I have a bed of perennial Egyptian onions for greens.) |

3 (Potato onions) |

1,000 seeds. (In addition, potato onions are planted from divided sets.) |

| Parsley |

3 |

Packet |

|

| Peas, Sugar Snap |

4 |

4 |

Leftover from last year |

| Peppers |

2 |

Packet |

|

| Poppies, Breadseed |

2 |

Saved |

|

| Squash, Butternut |

4 |

Saved |

|

| Squash, Summer |

8 (Succession planted) |

Saved |

|

| Strawberries |

4 (The goal is to rotate our entire planting every three years, so I remove four beds and plant four new ones every year.) |

Started from rooted runners in other beds |

|

| Sweet Potatoes |

4 |

I start my own slips from saved tubers. |

|

| Swiss Chard |

1 |

Saved |

|

| Tatsoi |

1 |

(Will order in fall) |

|

| Tokyo Bekana |

3 |

(Will order in fall) |

|

| Tomatoes |

15 (This is 30 plants) |

Saved |

|

| Watermelon |

4 |

Saved |

I hope that helps you get

a handle on how much of an area to plant and how many seeds to buy for

those of you planning big gardens this year. The table above is

geared toward Mark's and my tastes, of course, so I don't recommend that

anyone precisely mimic what we do. Total acreage (including small

perennials not mentioned here, extensive areas set aside for cover

crops, and aisles) comes to about a quarter of an acre, and the biggest cost for that vegetable garden is the straw we splurge on every year for mulch.

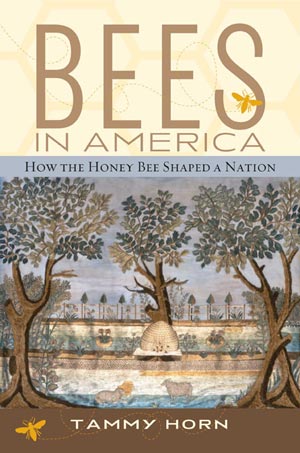

Our movie-star neighbor lent me a copy of Bees in America: How the Honey Bee Shaped a Nation,

by Tammy Horn, which turned out to be an interesting, if dense,

read. I'll start with the negatives, as usual. Bees in

America is put out by a University Press, which often means the text is

more scholarly than will be appealing to a layman audience. Horn's

book definitely pushes some of those "required reading" buttons, with

more primary citation and repetition than is fun for non-historians to

read.

Our movie-star neighbor lent me a copy of Bees in America: How the Honey Bee Shaped a Nation,

by Tammy Horn, which turned out to be an interesting, if dense,

read. I'll start with the negatives, as usual. Bees in

America is put out by a University Press, which often means the text is

more scholarly than will be appealing to a layman audience. Horn's

book definitely pushes some of those "required reading" buttons, with

more primary citation and repetition than is fun for non-historians to

read.

On the other hand, if

you're willing to do a bit of slogging and skimming, you'll find real

gems within these pages. The rest of this week's lunchtime series

will offer some insight into the history of beekeeping in America, so

here I'll just mention a couple of tidbits that didn't fit anywhere

else. Did you know that bees have been used as political and

social metaphors for centuries, being used to teach that labor is a

virtue and that the lower class is disposable in seventeenth century

England? And how about tanging, that tradition of banging pans or

drums or ringing bells when swarms pass overhead --- did you realize

tanging was originally meant to mark ownership of the swarm, not to make

the bees land in your yard? Stay tuned for other bee tidbits in

later posts.

| This post is part of our Bees in America lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We changed our mind about

using 28

inch flashing for the Star Plate roof.

A plywood roof will allow us

to crawl on it to install roofing felt and shingles.

It seems I was looking in the wrong spot for the first crocus of the year.

This beauty turned up Monday afternoon, but the flower was so bold that

I suspect it might have opened over the weekend. The main crop,

slowed down by the mulch under the peach tree, may be another week yet

(or more if the forecast snow storm pans out).

Meanwhile,

another sign of spring started peeping Saturday and popped out of the

incubator Sunday and Monday. The chick pictured here is number

two, and I'll post a rundown on hatch data next week on our chicken blog for the geekier set.

Meanwhile,

another sign of spring started peeping Saturday and popped out of the

incubator Sunday and Monday. The chick pictured here is number

two, and I'll post a rundown on hatch data next week on our chicken blog for the geekier set.

We start our chicks on Avian Aqua Miser Originals, since the waterers keep the brooder dry, prevent coccidiosis, and are just plain dependable. If you want to follow our lead, we've marked down this premade chicken waterer to $25 (with free shipping) this week!

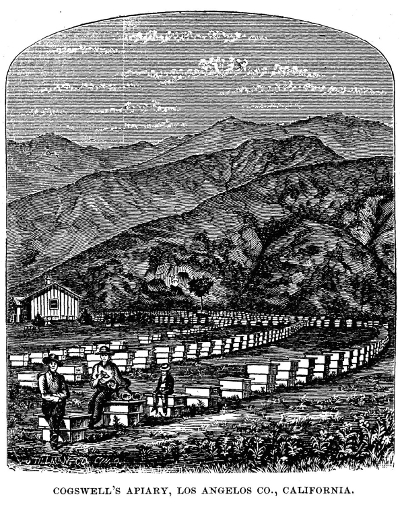

When honeybees came to America, they were brought across the ocean in straw skeps. In Bees in America,

Horn explains that these skeps were originally considered an innovation

in Europe since they replaced heavier logs and clay plots that were

difficult to move. Horn's book includes some interesting

illustrations of how skeps were constructed, and I was especially

intrigued to learn that ekes were often placed underneath skeps when the

bees needed more room, a bit like nadiring a Warre hive.

When honeybees came to America, they were brought across the ocean in straw skeps. In Bees in America,

Horn explains that these skeps were originally considered an innovation

in Europe since they replaced heavier logs and clay plots that were

difficult to move. Horn's book includes some interesting

illustrations of how skeps were constructed, and I was especially

intrigued to learn that ekes were often placed underneath skeps when the

bees needed more room, a bit like nadiring a Warre hive.

In addition to skeps,

early American beekeepers were fond of bee gums --- hollow logs used as

hives. Even though the inventor of the Langstroth hive (the

primary beekeeping box today) was an American, Horn reports that

colonists continued using bee gums and skeps long after the Langstroth

hive took over in Europe. Since skeps and bee gums don't allow for

much inspection and manipulation, their use may be one reason the U.S.

saw such a rash of pest and disease problems (which I'll cover in a

later post).

Speaking

of the Langstroth hive, it was one of four inventions that changed the

face of beekeeping in America between 1851 and 1873. During that

period, the bellows smoker, the movable frame hive, wax foundation, and

the centrifugal extractor (along with advances in queen rearing) changed

beekeeping from a hobby into an industry. More on the changing

face of beekeeping in America is to come in tomorrow's post.

Speaking

of the Langstroth hive, it was one of four inventions that changed the

face of beekeeping in America between 1851 and 1873. During that

period, the bellows smoker, the movable frame hive, wax foundation, and

the centrifugal extractor (along with advances in queen rearing) changed

beekeeping from a hobby into an industry. More on the changing

face of beekeeping in America is to come in tomorrow's post.

| This post is part of our Bees in America lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We made some more progress on

the Star

Plate chicken coop.

Roof construction got easier

once we figured out a proper place to put the ladder.

Spring

can't come early enough if you're a honeybee, eating through winter

stores and itching for more pollen to feed your new brood. This is

the first year our hybrid hazel

has really bloomed (albeit only male flowers so far), and the honeybees

are definitely enjoying the early pollen source. Previously,

crocuses have provided the first bit of protein for our bees, so I'm

thrilled to have hazels filling in the gap during such a late spring.

Spring

can't come early enough if you're a honeybee, eating through winter

stores and itching for more pollen to feed your new brood. This is

the first year our hybrid hazel

has really bloomed (albeit only male flowers so far), and the honeybees

are definitely enjoying the early pollen source. Previously,

crocuses have provided the first bit of protein for our bees, so I'm

thrilled to have hazels filling in the gap during such a late spring.

Of course, bees need more

than pollen --- they need nectar too. Many beekeepers feed sugar

water at this time of year to simulate an early nectar flow, thus

prompting the queen to lay more eggs sooner, bulking the hive up fast so

they're ready to take advantage of the tree flowers that will open in a

few weeks.

Previously, I've tried to

only feed our bees in the fall and only then if they didn't look like

they had enough honey to make it through the winter, but I'm relaxing my

standards this spring. We only have one hive left (the barn swarm having finally bit the dust during one of those subzero spells), and I want to be able to split

it this spring. Plus, I'd really like to be able to harvest honey

--- it seems crazy that we've been raising honeybees for so long and

have still been buying (or trading for) nearly all of our honey for the

last few years. Fancy techniques for raising honeybees only make

sense if you get some yield along with the bees.

Our

movie-star neighbor (aka my beekeeping mentor) recommends spring

feeding only if you commit to keep feeding until there are lots of

flowers around. The idea is that you don't want to get the hive

bulked up, then have a large colony starve because you stop feeding and

the spring flowers aren't open yet. To that end, I've kept a

feeder on the bees full time over the last two weeks, although they've

only eaten about 1.5 quarts so far.

Our

movie-star neighbor (aka my beekeeping mentor) recommends spring

feeding only if you commit to keep feeding until there are lots of

flowers around. The idea is that you don't want to get the hive

bulked up, then have a large colony starve because you stop feeding and

the spring flowers aren't open yet. To that end, I've kept a

feeder on the bees full time over the last two weeks, although they've

only eaten about 1.5 quarts so far.

As you can see from the photo above, our hive has a completely empty box

below their main brood chamber to expand into. We removed the

bottom board last week, so now I'll be able to keep an eye on the

colony's expansion and will report back about how the feeding campaign

impacts their spring bulk up. Only time will tell whether the

spring feeding is a good or a bad call, but I'll keep you posted either

way.

Some of the most vivid imagery in Bees in America

involves honey hunters and migratory beekeepers. Horn reports

that during the colonial era, American honey hunters would search

through the woods throughout the spring and summer looking for wild bee

trees. The journey would usually begin when the honey hunter set

out a plate of flour surrounded by flower petals, attracting and marking

the bees at the same time. By following the path of the now-white

bees through the air (a technique known as coursing), the honey hunters

were able to locate the bee tree, then to mark it with a slash on the

bark to demonstrate ownership. Come fall, when the bee tree was

full of honey, the honey hunter would return, cut down the tree, and

split the sweet profits with the landowner.

Some of the most vivid imagery in Bees in America

involves honey hunters and migratory beekeepers. Horn reports

that during the colonial era, American honey hunters would search

through the woods throughout the spring and summer looking for wild bee

trees. The journey would usually begin when the honey hunter set

out a plate of flour surrounded by flower petals, attracting and marking

the bees at the same time. By following the path of the now-white

bees through the air (a technique known as coursing), the honey hunters

were able to locate the bee tree, then to mark it with a slash on the

bark to demonstrate ownership. Come fall, when the bee tree was

full of honey, the honey hunter would return, cut down the tree, and

split the sweet profits with the landowner.

Another story that really

captured my interest involved French beekeepers in Maryland and

Pennsylvania in the 1600s. These early migratory beekeepers kept

their hives on flatboats, traveling at night and anchoring beside

flower-filled meadows each day to maximize their honey production.

Later, migratory beekeepers used the

railroad and then trucks to move their bees, being paid for pollination

(in addition to being able to sell their honey)

by the beginning of the 1900s. In fact, by the second half of the

twentieth century, pollination services had become more lucrative than

producing honey, with some beekeepers receiving $32 per hive placed in

almond orchards in the 1990s.

| This post is part of our Bees in America lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We did the first triangle

with horizontal supports.

Installing a vertical 2x4

down the middle of each triangle gives more support.

The Star Plate has holes to

secure the supports with a lag bolt, but we realized the alternative

smaller holes were easier with long exterior screws.

Dividing and replanting our chives

cluster in fall 2012 seems to have been a very good idea. The

three clumps did okay last year, but this spring, they're taking off

early and quickly. I was thrilled to realize this week that I now

have several meals' worth of fresh, oniony goodness  poking out of the ground, with more on the way.

poking out of the ground, with more on the way.

The only thing I would do

differently is to cut back the dead growth this autumn rather than

letting the top matter decay where it falls. The new leaves pushed

up right through the dead stems, so I had to pick a bit of straw-like

material out of the greenery before we could eat it. That didn't

take any of the fun out of a homegrown omelet made from our eggs and

chives and a bit of kefir-cultured sour cream, though. Delicious and simple spring goodness!

One of the most useful threads running through Bees in America

was the history of pests and diseases that have troubled American hives

nearly from the beginning. Foulbrood and wax moths were the

biggest issues in the early nineteenth century, and damage by the

greater wax moth seems to have been even more extreme that varroa moths

and colony collapse disorder are today. In fact, 80% of the

apiaries around Boston were abandoned by 1809 due to depredations of the

greater wax moth.

One of the most useful threads running through Bees in America

was the history of pests and diseases that have troubled American hives

nearly from the beginning. Foulbrood and wax moths were the

biggest issues in the early nineteenth century, and damage by the

greater wax moth seems to have been even more extreme that varroa moths

and colony collapse disorder are today. In fact, 80% of the

apiaries around Boston were abandoned by 1809 due to depredations of the

greater wax moth.

Being able to inspect

hives made a big difference in fighting both of these early pests once

Langstroth developed a hive with movable frames, and foulbrood became

even less common after a 1923 law outlawed bee gums and allowed bee

inspectors to burn hives when signs of the disease were apparent.

However, foulbrood remained a major problem among American beekeepers

until antibiotics were developed to fight the bacterium after World War

II. Unfortunately, some strains of the problematic microorganisms

became resistant to antibiotics by the 1990s, which led beekeepers to

begin using Integrated Pest Management, medicating hives only when signs

of foulbrood were evident. A similar strategy was used for varroa

mites, which entered the scene along with tracheal mites in the 1980s.

Pests

and diseases weren't the only hurdle honeybees had to face,

though. Pesticides drifting from farmer's fields into bee

territory became a major problem around the 1950s, and continued

throughout the second half of the twentieth century. The federal

government developed some methods of remunerating beekeepers for their

dead hives, but cash payouts didn't help the bees themselves.

Eventually, the worst pesticide, which came in grains that looked like

pollen to bees, was outlawed.

Pests

and diseases weren't the only hurdle honeybees had to face,

though. Pesticides drifting from farmer's fields into bee

territory became a major problem around the 1950s, and continued

throughout the second half of the twentieth century. The federal

government developed some methods of remunerating beekeepers for their

dead hives, but cash payouts didn't help the bees themselves.

Eventually, the worst pesticide, which came in grains that looked like

pollen to bees, was outlawed.

Horn's book ended with

the small hive beetle hitting Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, and

South Carolina in 1998, so no mention was made of colony collapse

disorder, which started showing up two years after the book was

published. It's interesting to put our current beekeeping woes in

perspective, though, and to realize that keeping bees in America has

always been a struggle against pests, diseases, and chemicals. As

I'll explain in tomorrow's post, trying out different bee varieties can

be part of the solution when new issues rear their ugly heads.

| This post is part of our Bees in America lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

How does the Star Plate

middle support 2x4 get attached to the top of each wall?

It took a bit of trial and

error to figure out the correct angle, but once we did it was just a

matter of securing 2 long exterior screws through the bottom section of

the wall.

There's nothing like a

cold, snowy night to send me off into the garden with vigor the next

day. I know better than to plant seeds when the ground is that

cold, but I figured I could get away with preparing beds for Friday's

pea and Swiss chard planting, soaking some peas to give them a jump

start, and even putting in broccoli, cabbage, and onion seeds in the

warmer ground under a quick hoop. (Yes, I did already start those last three crops in the house a few weeks ago, but I get better results outside most years. Plus, the main rule of homesteading is: Backups, backups, backups.)

Next, I headed out to the vole-girdled apple trees,

which I've been ignoring ever since seeing the damage. I'd

planned to try a bridge graft, using twigs from each tree to traverse

the gap between trunk and the bark-covered roots. However, after

digging for at least eight inches in all directions, I only found one

rooted area that wasn't all the way girdled. I don't hold out high

hopes for that little bridge graft to take, but I figured there was no

reason not to try it.

The final thread I enjoyed untangling from Horn's Bees in America

was the history about which types of honeybees were being raised in

American apiaries over the last few centuries. Horn reported that

the first bees to be brought to what would later become the United

States were German black bees. These scrappy bees quickly swarmed

into the wild and spread west ahead of the settlers, although they

needed help crossing the Great Plains.

The final thread I enjoyed untangling from Horn's Bees in America

was the history about which types of honeybees were being raised in

American apiaries over the last few centuries. Horn reported that

the first bees to be brought to what would later become the United

States were German black bees. These scrappy bees quickly swarmed

into the wild and spread west ahead of the settlers, although they

needed help crossing the Great Plains.

German black bees

continued to be the primary variety until the same Langstroth who

developed the Langstroth hive was involved in introducing Italian bees

to America. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century,

many different kinds of bees were imported from abroad, but Italians

soon became the most popular due to their gentleness. However, a

federal law in 1922 outlawed further imports of foreign bees in an

effort to block out the Isle of Wight disease.

For a while, Americans seemed perfectly happy with what they had, but the pests and diseases

that kept cropping up in apiaries made some beekeepers itch to import

new varieties again. Horn reports that, while American bees have

largely been bred to similar genetics for the most efficient honey

production, Europe has a more artisanal approach to honeybees, with lots

of different varieties available for different purposes.

Especially after tracheal and varroa mites arrived in the U.S. in the

1980s, many American beekeepers realized that finding more resistant

bees was a better approach than dousing hives in chemicals, and in 2004,

the federal law against importing honeybees was overturned.

In

the meantime, nature was filling in the gap. Africanized

honeybees (popularly known as "killer bees") are survivors, able to find

nectar in a dearth, to

build up to swarm size quickly, and to defend the hive

aggressively.

The bees were introduced on purpose in Brazil in the 1950s, but they

quickly swarmed

north, resulting in many terrified efforts by the U.S. government to

prevent the influx of so-called killer bees. By the time the

variety reached the Texas border, though, we realized the problem wasn't

as severe as we'd imagined, although policies continue to isolate bees

along border counties to slow their spread. When Horn's book was

published, Africanized

honeybees were only found in California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada,

Oklahoma, Kansas, Texas, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands since cold

and

humidity seem to be preventing the bees from spreading further north and

east.

As long-time readers will

know, we've had a lot of trouble keeping honeybees alive without

chemicals, and the only hive that has so far gone the distance is a colony of bees bred in Texas using some Africanized genetics.

Yes, our part-killer bees are a little meaner than any of the other

colonies we've had, but they also seem able to live without any

medications at all (so far). While that's a very small sample

size, it makes me wonder if we should be terrified of Africanized bees,

or if we should embrace the spread of honeybees that seem able to handle

modern problems with aplomb. I'd be curious to hear from others

who have dabbled in chemical-free beekeeping --- do you think a slightly

meaner hive is worth the tradeoff for simpler beekeeping?

| This post is part of our Bees in America lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We installed the last plywood

triangle today.

Having the roof support done makes it

feel more like a chicken coop.

Whatever magic Daddy worked on this little tomato plant,

the effects have been quite impressive. Despite leaving his

climate-controlled sunroom to live in our not-too-sunny trailer where

the night lows can drop into the 30s, the plant has continued to bulk

out and thrive.

Friday, I noticed that

the plant was already sending roots out the bottom of its half-gallon

pot, so I potted it up into a two-gallon container, sinking the tomato

plant deep enough so that the first set of leaves are only barely

visible above the soil line. Tomatoes root well from the stems, so

this will give the plant more root area and will prevent it from

getting leggy, even though the plant doesn't seem to have any problems

in that area.

I'll be very curious to

see how big this little guy gets in the next two months before our

frost-free date, and whether it gives us ultra-early tomatoes.

Daddy plans to upgrade his tomato all the way to a five-gallon bucket

while it's indoors, then to dig the plant a huge hole with post-hole

diggers. I may have to follow suit.

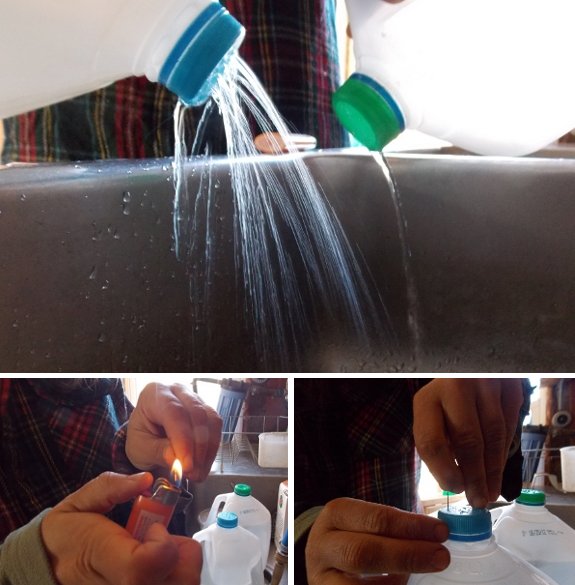

How do you get that slow,

smooth spray from a DIY plant watering can?

Heat a needle and then push

holes through the cap.

A lot easier than going out

to the store to buy one made in China. A smooth spray allows for more

even watering compared to a quick dribble.

How's the sky pond doing, you may be wondering? (Okay, you probably weren't, but I was.)

From a distance, the answer would be --- not good. It got too muddy for me to replace the gutter line

Lucy tore up, so the area I was trying to channel water out of is pure

mud. Not very photogenic or efficient to walk through.

But Lucy reminded me to look closer....

In the pond itself, I was

surprised by the masses of living things waking up from the cold

winter. There are probably hundreds, if not thousands, of these

little water snails lining the walls, eating decaying vegetation.

Last summer, the parrot's feather and duckweed really took off, and most

of the plants didn't survive the winter, so there's plenty of

decomposing vegetation in the pond now to feed the snails. If I

could think of an easy way to harvest them, I suspect I could get enough

protein out of these little critters to feed our flock for a day or

two, leaving plenty of snails behind to repopulate the pond.

I don't know if the

parrot's feather will come back to life, but the duckweed is already

spreading across the surface. The chorus frogs moved in about a

week ago, and have been yelling in Mark's ears ever since, leaving

behind their little clusters of eggs that will soon turn into

tadpoles. And lots of little water insects are scurrying about in

the water. Maybe Mark's right and this pond could host a goldfish

or two this year.

Pushing the Star Plate triangles above the top creates enough space at the bottom to have room to stand while securing the plywood to the frame.

While I wasn't looking,

the garden started to grow. I'd been a bit concerned that our

overwintering garlic couldn't stand this winter's extremes, but the

plants are starting to push out new leaves. The rye cover crop

I have on other beds is also filling in and growing up, and I can see

hints of new leaves amid the strawberries. I try to ignore my

father's South Carolina reports of first asparagus, though --- I don't

expect to see any of that for at least two weeks, if not longer.

Although I'm planting

little bits and pieces of early crops in the main gardens, my eye is

most drawn to the sunny patch in front of the trailer. Due to Mark's hard work on the gutter and Kayla and my dirt-hauling,

the ground there is finally well-drained enough to grow non-aquatic

plants, so I've put in some peas to begin shading the window before the

kiwi and grapes get their feet under them. The old saying goes

that perennial vines take three years to get established: first they

sleep, next they creep, and finally they leap. During those

sleeping and creeping years, I'll fill in their habitat with something

annual.

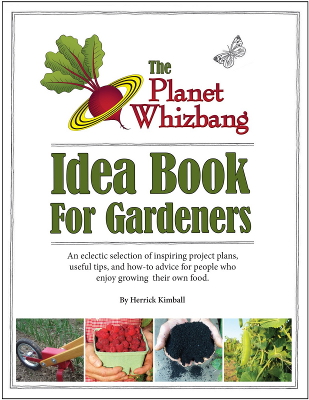

I usually find something negative to say about every book (along with lots of positives), but Herrick Kimball's The Planet Whizbang Idea Book for Gardeners

is an exception. This is self-publishing at its best --- quirky

but polished. If I had to say something negative, I'd beg for an

index, but the table of contents is really specific enough to help you

find projects within its pages. Other than that, there's nothing

not to love about the Idea Book.

I usually find something negative to say about every book (along with lots of positives), but Herrick Kimball's The Planet Whizbang Idea Book for Gardeners

is an exception. This is self-publishing at its best --- quirky

but polished. If I had to say something negative, I'd beg for an

index, but the table of contents is really specific enough to help you

find projects within its pages. Other than that, there's nothing

not to love about the Idea Book.

The instant you open The Planet Whizbang Idea Book for Gardeners, you'll be drawn in by the simple line drawings that are informative but also fun. Think of Bill Mollison's Introduction to Permaculture

and you've got the right idea. I don't know why, but projects

always look simpler with line drawings. However, if you want

photographic proof that Kimball's projects are possible, you'll also be

pointed toward a hidden website as soon as you buy the book, which

allows you to see plenty of photos of the author's work in action.

I'll write more about the

projects themselves in later posts, but suffice it to say that many

sound quite intriguing. Kimball also did a great job of excerpting

gardening advice from books and magazines of the 1800s, which is a time

when gardening was a serious fact of life for most people. I

thoroughly recommend the chapter by E.P. Roe titled "How to Grow

Strawberries of the Largest and Finest Quality" --- the method outlined

is nearly identical to the one I use, which produces berries so large

and delicious that everyone wants to visit us in May and June.

Okay, I did think of one more negative. Once you buy a copy of The Plant Whizbang Idea Book for Gardeners, you'll realize you need to buy two more to give away as gifts. But that's a good problem, right?

| This post is part of our Idea Book for Gardeners lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

How much weight can a chicken

lift or push through?

We've had a rebellious hen

pushing her way through our home

made dog door to scratch up the garden mulch.

Hopefully these two pieces of

furring strips will be enough weight to stop a hen while at the same

time allowing Lucy to still push through.

Daddy's rule of soup is:

"Choose your pot wisely, because soup will expand to fill the space

provided." My rule of indoors plants is: "Don't buy potting soil

because your plants will expand to fill the soil available." Since

I found a second stump dirt tree this year, that means I've been having fun starting more seeds inside than usual.

In

a perfect world, seedlings in flats would be potted up soon after they

emerge into larger containers with higher-fertility soil. My

seedlings don't usually enjoy that perfect world, but I figured my

tomatoes deserved a bit of pampering this year. So I mixed an

equal quantity of stump dirt and well-composted horse manure in the

wheelbarrow and used that mixture to fill individual pots for the baby

tomatoes. This way, the plants can keep growing without hitting

any boundaries, which is what keeps seedlings big and strong.

In

a perfect world, seedlings in flats would be potted up soon after they

emerge into larger containers with higher-fertility soil. My

seedlings don't usually enjoy that perfect world, but I figured my

tomatoes deserved a bit of pampering this year. So I mixed an

equal quantity of stump dirt and well-composted horse manure in the

wheelbarrow and used that mixture to fill individual pots for the baby

tomatoes. This way, the plants can keep growing without hitting

any boundaries, which is what keeps seedlings big and strong.

The broccoli, cabbage,

and onion seedlings will go out in the garden much sooner, so I opted

for a lazier approach to their health. Instead of  potting

up, I simply soaked some composted manure in water and used that rich

tea to water the seedlings right in their flats. Stump dirt is

relatively low in nitrogen, so this should give the seedlings a boost

without requiring the extra space that larger pots would require.

potting

up, I simply soaked some composted manure in water and used that rich

tea to water the seedlings right in their flats. Stump dirt is

relatively low in nitrogen, so this should give the seedlings a boost

without requiring the extra space that larger pots would require.

Of course, emptying out

the tomato flat meant that I had an extra flat on hand, and I had just

enough stump dirt leftover from my weekend walk to fill that flat

up. So I started a few more varieties of tomatoes, some peppers,

Malabar spinach, and even a few zinnias. It's a good thing I've

run out of stump dirt for the moment because I've also run out of space

to put plants in front of sunny windows....

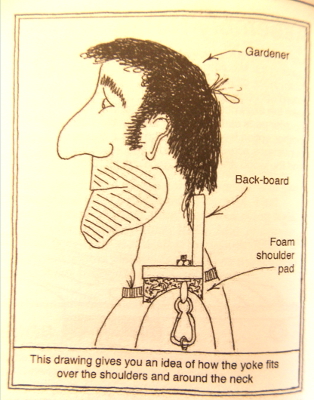

If I had to pick a single project in The Project Whizbang Idea Book for Gardeners

that is the most useful, it would probably be the shoulder yoke.

Call me crazy, but I've wanted a yoke for years. The idea is that

by balancing a load on a piece of wood that spans your shoulders, it's

much easier to carry heavy things. And while wheelbarrows provide

lower-work hauling on level ground, a yoke would make many of our jobs much simpler during mud season or when wandering through the woods in search of stump dirt.

If I had to pick a single project in The Project Whizbang Idea Book for Gardeners

that is the most useful, it would probably be the shoulder yoke.

Call me crazy, but I've wanted a yoke for years. The idea is that

by balancing a load on a piece of wood that spans your shoulders, it's

much easier to carry heavy things. And while wheelbarrows provide

lower-work hauling on level ground, a yoke would make many of our jobs much simpler during mud season or when wandering through the woods in search of stump dirt.

The trouble with make a

yoke is that the tools are traditionally carved out of a solid piece of

wood, and most of us don't have that skill. Enter the Plant

Whizbang shoulder yoke, which is built by screwing together three pieces

of 1X6, plus a little hardware and padding.

Mark and I are both

itching to give this project a try, so hopefully you'll hear more about

it in later posts. In the meantime, I've included one of Kimball's

drawings to get you thinking about homemade shoulder yokes. (I

highly recommend checking out the rest of the chapter, though, to

simplify constructing your own yoke.) And if you beat us to this

project, I hope you'll send in a photo of your finished project along

with a note about how it works for you!

| This post is part of our Idea Book for Gardeners lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We decided to use 28 inch

flashing material to cover the Star Plate

plywood.

Each piece gets overlapped by

6 inches and attached with small drywall screws.

Anna: We had a hatch problem and these guys are supposed to be our replacement layers for next year. What shall we do to fill in the gap?

Anna: We had a hatch problem and these guys are supposed to be our replacement layers for next year. What shall we do to fill in the gap?

Mark: How about we buy a few chicks at the feed store to add to our miniature flock?

Anna: Ooh, that sounds like fun! What about ducks?

Mark: Who said anything about ducks?

Anna: Ducks! What a great idea! The feed store has Pekin, or we could buy Khaki Campbell from a local farmer. Pekin are really for meat, so the Khaki Campbell would be a better bet....

Mark: Calm down.

Weren't we talking about chicks? You know, baby chickens that we

already know how to raise and have the equipment for.

Anna: Or I could look

online and see which varieties are available there. Hmmm, let me

look through my books, too, and find out what types my favorite authors

recommend.

Mark: Hello? Are you listening to me.

Anna:

Ancona ducks! That's a great idea, honey. We'll order some

Ancona ducks from Cackle Hatchery, and throw in 25 Cornish Cross chicks

while we're at it to explore that meat variety. It's too late to

raise them with our current chicks, so we'll get the chicks and

ducklings near the end of April and skip our usual second homegrown

hatch of the year.

Anna:

Ancona ducks! That's a great idea, honey. We'll order some

Ancona ducks from Cackle Hatchery, and throw in 25 Cornish Cross chicks

while we're at it to explore that meat variety. It's too late to

raise them with our current chicks, so we'll get the chicks and

ducklings near the end of April and skip our usual second homegrown

hatch of the year.

Mark: Where will these hypothetical ducks live?

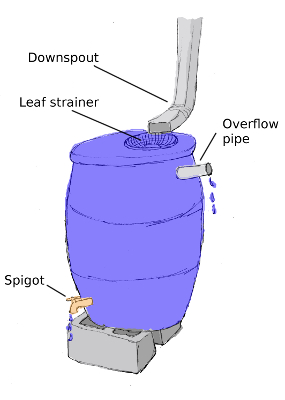

Anna: In the starplate coop

with our new layers! Ducks grow faster than chickens, so we

should be able to mix the two relatively young. We can collect

rainwater off the roof to make them a little pond. Maybe make it

drain into the swales above the apple trees for fertigation like in The Resilient Farm and Homestead.

Mark: Isn't that a lot of work?

Anna: Well, the new layers were going to go there anyway. And

Cornish Cross grow so big and fast, buying them will really make our

broiler endeavor easier this year. Did you know ducks lay better than chickens do in the winter?

Mark: Is this what you really want?

Anna: Can I have ducks if I don't beg for pigs or sheep this year?

Mark (rolling his eyes): Okay, ducks it is.

(Stay tuned for the more serious explanation of why we're trying ducks on our chicken blog next week. Or mark your calendars for more fluff April 25!)

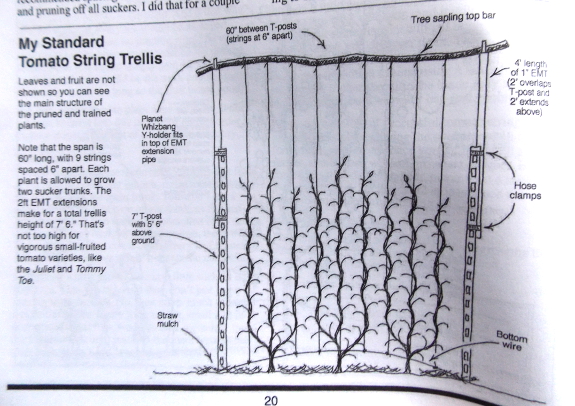

The second project I'm

itching to try out this year is training tomatoes onto a string

trellis. As long-time readers know, fungi thrive in our wet

climate and we're always battling blight on tomatoes. We already stake carefully and prune heavily,

but Kimball's idea of separating out the three stems to each be

supported by one vertical line is a very good one. Since we have

some space below our new grape/kiwi trellis

this year, I'll try two or three tomatoes there using Kimball's string

method, and may also experiment with adding additional supports for my

other tomatoes so I can separate out their three stems more carefully as

well. (In the past, I've trained to three stems, but have tied

them all to one stake.)

While I'm talking trellising, I should add that The Planet Whizbang Idea Book for Gardeners

is full of trellises and other structures based on t-posts. I

have a feeling that Kimball loves t-posts as much as Mark loves 5-gallon

buckets, so if you have an equal affinity for the lowly t-post, you

should definitely give his book a try. You'll find t-posts turned

into grape trellises, pea trellises, hops supports, bird feeder

supports, and much more.

| This post is part of our Idea Book for Gardeners lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The very top of the Star

Plate roof is hard to reach safely.

Our solution was to fabricate

a 5 sided pyramid cap.

Anna gets a Gold Star today

for figuring out the complicated angles.

One of my biggest goals for 2014 was to pick one holiday per month that meant something. January, I made up Inflection Day, and we celebrated Imbolc

in February. March is one of the easy months since it has an

obvious holiday --- the Vernal Equinox (aka the first day of spring, for

those less geeky than me).

It's a real joy to wake

at first light at this time of year and still have a couple of hours of

daylight after supper. (We're early diners.) The last week

has featured the first butterflies of the year (a comma or question

mark, plus several spring azures), frog calls have turned into a frenzy,

and the "weedy" wildflowers like speedwell and purple dead nettle are

starting to bloom. I even saw a bat out swooping up the first

spring insects!

The Egyptian onions are growing like crazy, making this a great time to cook up some of the last butternuts into butternut soup.

We've also been enjoying the first kale leaves and will soon be eating

lettuce. The hunger gap is starting to close!

Happy spring!

I enjoyed reading Kimball's chapter on making tire

garden beds not so much because I want to follow his lead, but because I

like hearing about working with tires. I'm still looking for the

perfect use for this waste product on our own homestead, so his ideas

were welcome.

When making garden beds out of tires, Kimball recommends cutting off the

sidewalls with a jigsaw to turn your tire into a more space-saving

container. After removing the sidewalls, he turns the remaining

part of the tire inside out, which makes it a bit more vertical (and

hides the tread). Finally, Kimball learned the hard way that it's

best to sink your tire into the ground if you don't want your crops to

dry out.

Where do I see potential

for using tires on our farm? If I'd been smart, I would have sunk a

processed tire into the ground as a root barrier before planting my

mint. And I could see using tire raised beds to help me build the

soil up in the forest garden, where the groundwater is so close to the

surface that roots often drown. I'll bet you can come up with even

more good ideas for using tires in the garden --- feel free to share

them in the comments section!

| This post is part of our Idea Book for Gardeners lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

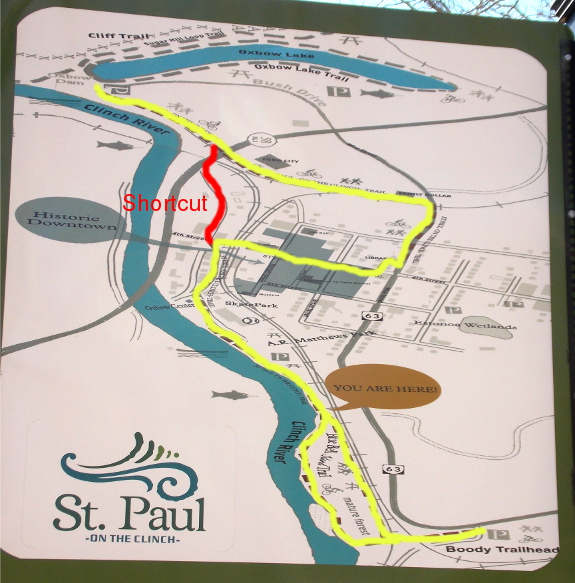

We took the afternoon off to

celebrate the first day of Spring.

Exploring a new trail is one

of our favorite kind of day trips.

The new Boody Trail had a

nice mix of low impact river walking along with some flavor of the

downtown portion of St Paul.

Sugar Hill

is our closest park with good walking trails (at least as the car

drives), but Mark and I haven't been there for a while. We've

already explored the whole place, so we generally want to go somewhere

new.

Sugar Hill

is our closest park with good walking trails (at least as the car

drives), but Mark and I haven't been there for a while. We've

already explored the whole place, so we generally want to go somewhere

new.

But we didn't feel like driving far Thursday, and when we showed up at

Sugar Hill we were delighted to discover that a new trail has been added

to the mix! How's that for proof that Mark can manifest anything?

Boody Trail is more of a

city walking trail than a naturalist's

hiking trail, but the length is just right (two miles each way, with

some loop potential), and an easy walk along the river sounded like

fun.

Plus, the Bluebell Trail portion at the east end (bottom of the map

above) is a nice chunk of

floodplain, with beautiful sycamores and Virginia bluebells poking up

through the floodplain sand. Like the rest of the trail, there are

lots of invasive plants present (Japanese Knotweed in the Bluebell portion of the trail), but I was interested to see that native cane

was also being planted --- I'll have to check back and see if the

canebrake can outcompete the knotweed. This one-mile loop is the

portion of the trail I'm likely to walk again.

Another three-quarters of

a mile of Boody Trail wiggles through the heart of St. Paul.

Since I hadn't seen a map at this point, following the little white

signs felt a bit like a treasure hunt, and it reminded me of my days of

walking around another town as a kid. It was fun to pass by my

favorite spot in St. Paul (the library) and to walk on a new little

pedestrian passage under the bridge, but on the way back, we took a

shortcut across the railroad tracks to cut out this portion. Mark

and I agreed that if we had

to live in town, St. Paul, Virginia, might be the town we'd live

in. No way we'd trade in our mud and acreage for city streets,

though.

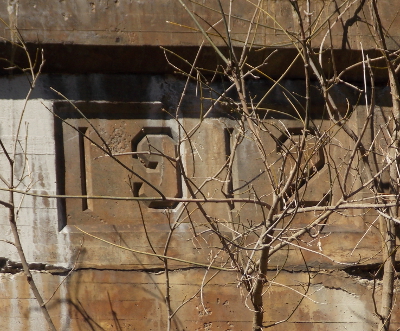

A lot of the trail ran near the railroad, which provided nice views of old bridges. The one Mark pictured yesterday

was the prettiest, and was dated to 1912. The bridge above,

wasn't as old, but has its own appeal. There's even a caboose

parked along the trail at one point, which I suspect would be of

interest to people with kids. If you're a trainspotter, I

understand that "This is a mega cool spot."

A lot of the trail ran near the railroad, which provided nice views of old bridges. The one Mark pictured yesterday

was the prettiest, and was dated to 1912. The bridge above,

wasn't as old, but has its own appeal. There's even a caboose

parked along the trail at one point, which I suspect would be of

interest to people with kids. If you're a trainspotter, I

understand that "This is a mega cool spot."

All

in all, Boody Trail made for a fun adventure. No real wildflower

or wildlife sightings, but I enjoyed seeing the first dandelions of the

year along with daffodils in full bloom. Towns are definitely good

places to go if you want to pretend you live a week in the future,

weatherwise.

All

in all, Boody Trail made for a fun adventure. No real wildflower

or wildlife sightings, but I enjoyed seeing the first dandelions of the

year along with daffodils in full bloom. Towns are definitely good

places to go if you want to pretend you live a week in the future,

weatherwise.

By the way, in case

you're curious, I believe Boody Trail is named after the road at one of

its trailheads. I'm not sure what the road is named after,

though. If you know, please do comment!

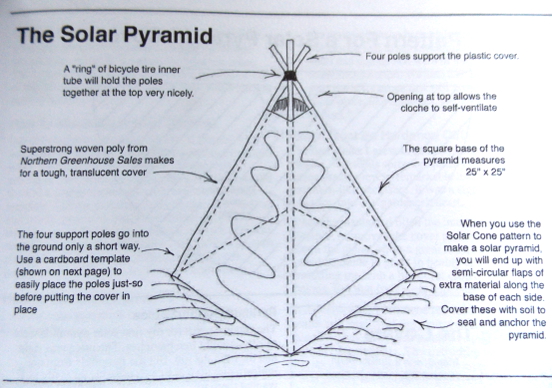

The last set of projects that caught my eye in the Planet Whizbang Idea Book for Gardeners were for season extension. Kimball's caterpillar cloche system is very similar to my quick hoops,

and although I prefer most of my methodology, I might try his technique

of staking a line alone each side of the hoop and attaching the fabric

to the line with clothespins, rather than rolling the fabric in rebar

(my current method).

I also like Kimball's

solar pyramid idea, although I'd probably tweak his design there as

well. He uses an expensive plastic to cover the pyramid, and I'd

instead use some of the scraps of row-cover fabric that have become too

tattered to be used on quick hoops. Maybe a solar pyramid would

allow me to plant out Daddy's huge tomato in April rather than May?

| This post is part of our Idea Book for Gardeners lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The top of the Star

Plate pyramid is a pentagon cut from a piece of 2x6.

How did we determine the size

and angles of the pentagon?

We guessed on the size and

did an image search for pentagon, printed it on paper and then used it

as a template to trace where to cut.

In

March, when the sun shines so bright and you can strip down to a

t-shirt and sandals, weeding is pure bliss. Kayla came over and

helped me pluck the speedwells, dead nettles, and chickweed before they

had a chance to go to seed. We cleaned up around the kale, pulled

running perennial grasses out of asparagus alley,

and started prepping beds for late March planting. Weather

permitting, carrots, parsley, and maybe a few cabbage transplants will

go in next week, then the week after that we'll be busy planting onion

transplants and parsley.

In

March, when the sun shines so bright and you can strip down to a

t-shirt and sandals, weeding is pure bliss. Kayla came over and

helped me pluck the speedwells, dead nettles, and chickweed before they

had a chance to go to seed. We cleaned up around the kale, pulled

running perennial grasses out of asparagus alley,

and started prepping beds for late March planting. Weather

permitting, carrots, parsley, and maybe a few cabbage transplants will

go in next week, then the week after that we'll be busy planting onion

transplants and parsley.

Now that the spring firsts

have started, I can feel the warm season gaining momentum.

Thursday, I saw the first few sprouts from our early planting of peas,

the elderberries are starting to poke out a few leaves, and the first

daffodil opened Friday.

Now that the spring firsts

have started, I can feel the warm season gaining momentum.

Thursday, I saw the first few sprouts from our early planting of peas,

the elderberries are starting to poke out a few leaves, and the first

daffodil opened Friday.

I know that I post photos

of the same signs of life every year, but each glimpse of spring

continues to excite me. I hope I never stop getting a burst of

pure pleasure each time I see new signs of plants and animals overcoming

the winter cold.

We moved our new chicks to

the outdoor

brooder this week.

Lucy is always interested in

what we're doing and keeps her distance when the chicks get brave

enough to forage out from their new home.

Okay,

yes, I'm aware that werewolves have nothing to do with

homesteading. But reading paranormal fantasy is one of my favorite

leisure-time activities --- I can't always be researching ducks and

permaculture or Mark would go crazy keeping up with all of my flights of

fancy.

Okay,

yes, I'm aware that werewolves have nothing to do with