archives for 02/2014

Many of you have written in to sing the praises of kefir, but others have asked how to get started. Luckily, Brandy

is overflowing in milk kefir grains at the moment, and she's willing to mail

a starter culture (about two tablespoons of grains, enough to culture a pint right away, a $50 value) to two lucky winners

next week. To sweeten the pot, I'm going to throw in a paperback

copy of Lollipops, Garlic, and Basement Salamanders and a Walden Effect t-shirt for each winner. (These will come in a separate envelope, so you'll get two jolts of homesteading happiness if you win!)

Many of you have written in to sing the praises of kefir, but others have asked how to get started. Luckily, Brandy

is overflowing in milk kefir grains at the moment, and she's willing to mail

a starter culture (about two tablespoons of grains, enough to culture a pint right away, a $50 value) to two lucky winners

next week. To sweeten the pot, I'm going to throw in a paperback

copy of Lollipops, Garlic, and Basement Salamanders and a Walden Effect t-shirt for each winner. (These will come in a separate envelope, so you'll get two jolts of homesteading happiness if you win!)

How do you enter?

I've decided to try out a rafflecopter giveaway. At the moment,

what we really want to push is for our loyal readers to follow this link to Amazon,

bookmark the page, and use it when you make your usual orders.

We'll get a small cut of each order you place through that link, which

will allow us to mail out care packages like this. (In fact, Mark

wants to get in the habit of having some homesteading goodies to share

every month, but that will depend on how well the Amazon experiment

goes.)

Click on the relevant boxes below to enter! Thanks for reading, and I hope you enjoy the giveaway!

a Rafflecopter giveaway

What's the best way to secure

8 jugs of water to the back of an ATV?

Thread a flat

bungee cord through the handles and secure each end.

If you're sick of winter, today's the day to celebrate. In some traditional cultures, the February cross-quarter

isn't just a time to watch groundhogs, it's considered the first day of

spring! Countries that are now part of the United Kingdom used to

celebrate today as Imbolc, referring to the pregnancy of sheep.

Some customs that could still be relevant involve lighting candles or

fires to represent the increasing warmth, eating butter and milk to

celebrate the birth of farm animals, and divining the weather.

Divining

the weather? Yep --- Groundhog's Day probably derived from the

belief that a supernatural hag gathers her firewood on Imbolc to stay

warm for the rest of the winter. If it's going to be an extended

winter, she needs Imbolc to be warm and sunny so she can bring in lots

of wood. That's why if the groundhog (or snake or badger,

depending on who you talk to) sees its shadow, you're in for more cold

weather.

Divining

the weather? Yep --- Groundhog's Day probably derived from the

belief that a supernatural hag gathers her firewood on Imbolc to stay

warm for the rest of the winter. If it's going to be an extended

winter, she needs Imbolc to be warm and sunny so she can bring in lots

of wood. That's why if the groundhog (or snake or badger,

depending on who you talk to) sees its shadow, you're in for more cold

weather.

Another tradition

involves holy wells (any small water source with healing folklore

attached to it). Imbolc was considered a good time to visit these

holy wells, leaving offerings, using the water to bless things, and

walking sunwise around the well.

I preemptively celebrated

on Saturday by setting up my new tent on top of Beech Hill and basking

in the sun. The jury's still out on which other celebrations

we'll come up with today.

This post is to document how

thick the tank ice is. 8 inches.

Last night was warm and all

it took to break through was the bottom of the bucket, but on most days

of this January it took a few minutes chipping away at it with the spud bar.

Maybe after collecting a few

decades of this data on Imbolc day it will prove to be some sort of

indicator on how much more below freezing weather we can expect for the

rest of the Winter?

I'm going to take a wild

guess and say years with ice thicker than 5 inches on Imbolc day would

most likely equal a more mild February and March just because Mother

Nature likes to be mysterious when she can.

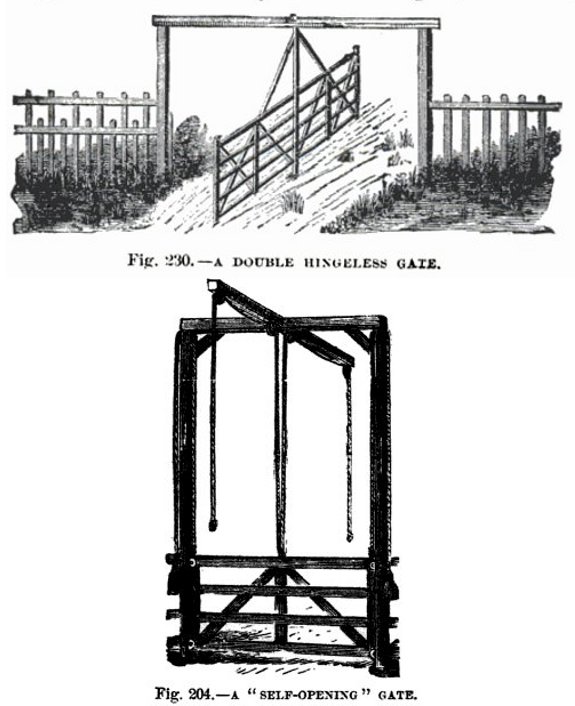

Upgrading one section of fence

and plugging in the deer deterrent seems to have been sufficient to nip

last month's deer incursion in the bud. It's hard to say how much

Lucy helps with these problems --- I do sometimes catch her on the game camera barking at the boundaries, but I've also seen deer in the yard with Lucy sound asleep and not noticing.

One of these days I'll

write an ebook on the topic, but for now, here's a rundown on the

utility of various deer-deterrent techniques. We've tried

everything on this list, and I've organized your options from most to

least effective. I hope the summary helps those of you with high

deer pressure. (Just so you know how high our pressure is --- one

neighbor killed 18 deer last fall, I suspect the other neighbor got at

least half a dozen, I got 1, Lucy got or found 1, and there are still deer everywhere.)

- Fences --- Moats,

especially, are multi-purpose, relatively low-cost ways to keep deer

out. A taller, more solid fence would obviously work even better,

but would cost many times more (and wouldn't double as a chicken

pasture!).

- Deer deterrents --- Mark's deer deterrents

are my favorite of the ones I've used, although they wouldn't fly in

suburbia. You really need at least four of these deterrents per

acre (probably more, and moved every few weeks) for total protection,

but the deterrents gave us perhaps 75% protection even before we erected

fences. Other scare-based deterrents we've used have been worthless for large gardens.

Spot covers ---

As a short-term fix while getting a more permanent solution in line,

plastic trellis material over especially tasty beds (like strawberries)

does work. Similarly, I've had good luck using one fencepost and

some trellis material to make a cage around young trees that are outside

our perimeter.

Spot covers ---

As a short-term fix while getting a more permanent solution in line,

plastic trellis material over especially tasty beds (like strawberries)

does work. Similarly, I've had good luck using one fencepost and

some trellis material to make a cage around young trees that are outside

our perimeter.

- Hunting --- This is really

only effective if you're willing to kill deer out of season and to fire

at any animals you see in your yard. Deer are creatures of habit,

and I suspect that when we have a repeated incursion, it's the same

individuals coming in over and over, so killing that problem deer can

make a difference. You can get a kill permit

for shooting deer in your garden out of season, but the permit we got

only lasted a short time and didn't feel worth the hassle.

- Dogs --- Their utility

really depends on the dog. As I mentioned above, Lucy is sweet,

but probably only keeps deer out 15% of the time since she naps most

nights and deer are most active in the dark.

- Sprays, soap, etc. --- These are completely useless in our climate. If you have one prize plant and don't live in rainy climate, this might work better for you, but you have to reapply after each rain on all plants you want protected. Meanwhile, the local standbys of tying smelly bars of soap to a tree or pouring cheap cologne on the ground are completely worthless as well.

Why am I posting about

keeping deer out of the garden at the beginning of February when

nothing's growing? This is the time to figure out your campaign

for the year, because if a deer gets used to coming into your yard in

the winter, it's going to be triply hard to keep it out in the

summer. That's why we ramp up our defenses immediately at the

slightest incursion. Good luck!

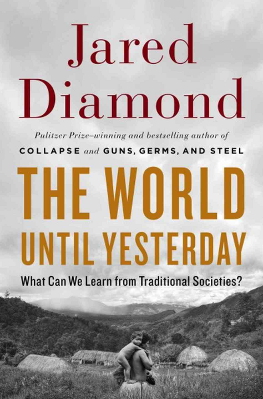

In The World Until Yesterday, Jared Diamond compares

traditional societies with the more-mainstream modern culture in an

effort to answer the question posed by the subtitle --- "What can we

learn from traditional societies?"

Diamond draws upon his extensive experience with the people of New

Guinea (many of whom had no contact with Western society until 1931),

along with data from other researchers about hunter-gatherer groups

around the world, to reach wide-ranging conclusions about how

traditional people interacted, what they ate, and how they lived.

In The World Until Yesterday, Jared Diamond compares

traditional societies with the more-mainstream modern culture in an

effort to answer the question posed by the subtitle --- "What can we

learn from traditional societies?"

Diamond draws upon his extensive experience with the people of New

Guinea (many of whom had no contact with Western society until 1931),

along with data from other researchers about hunter-gatherer groups

around the world, to reach wide-ranging conclusions about how

traditional people interacted, what they ate, and how they lived.

In the process, Diamond doesn't sugar-coat the reality of traditional

societies, admitting that warfare, infanticide, and many other aspects

of these cultures are things we're glad to be rid of. However, he

does suggest other features of traditional societies that we can

selectively incorporate into our own culture to improve our lives.

The book is a bit hit or

miss, with some chapters stating the seemingly obvious, while others

delve deep into fascinating topics I'd never considered. It's also

data heavy, perhaps because the author's Guns, Germs, and Steel

opened Diamond up to wide-spread criticism from historians. What I

only realized after reading this later book, though, is that Diamond is

an anthropologist, not a historian, so his conclusions are more about

broader issues of the human experience than they are about factual

histories.

Later posts in this week's lunchtime series are going to suggest homesteading-related implications of Jared Diamond's The World Until Yesterday.

However, I'll skip over discussing about two-thirds of the book, either

because I don't feel like I have the know-how to rehash certain

assertions (like his parenting tips), or because I don't want to open an

un-homesteading-related can of worms (for example, about Diamond's

analysis of the purposes of religion). Which is a long way of

saying --- if what you read here sounds interesting, this is one book

you'll want to delve into more deeply on your own.

| This post is part of our The World Until Yesterday lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We lost one of our White

Leghorn hens to a predator last night.

It may have been a raccoon.

What

exactly killed our chicken

might remain a mystery, but the link has a list of questions that helps

in making an educated guess on the predator's identity.

A cold winter is proof that we need to plan our spring planting schedule by soil temperature,

not by the calendar. For example, my garden spreadsheet says it's

time to seed lettuce under a quick hoop and start onions in a flat

inside. But, although the latter will be feasible once I thaw the stump dirt I hacked out of a tree in the woods, the former needs to wait. Despite preheating the lettuce bed, my thermometer

is still reading below freezing just beneath the surface there.

The beautiful weekend just past only managed about a quarter-inch

thaw.

Modern-day

homesteaders try to grow a lot of our own food, but we know we can

always head to the grocery store if a crop fails. Most members of

traditional societies, though, would be faced with starvation if they

didn't find ways to hedge their bets. Diamond

presented a slew of methods these traditional hunter-gatherers and

farmers used to ensure they always had food to eat, and some of these

techniques could be mimicked by modern homesteaders.

Modern-day

homesteaders try to grow a lot of our own food, but we know we can

always head to the grocery store if a crop fails. Most members of

traditional societies, though, would be faced with starvation if they

didn't find ways to hedge their bets. Diamond

presented a slew of methods these traditional hunter-gatherers and

farmers used to ensure they always had food to eat, and some of these

techniques could be mimicked by modern homesteaders.

My favorite example came from the Peruvian Andes, where farmers scattered small

garden plots across several

miles. Each farmer owned an average of 17 fields, each about 250

square feet in size, so the farmers were gardening a tenth of an acre

spread across many tiny

plots. To modern farmers, this method seems very inefficient

because the Peruvian farmers spent a lot of their time walking back and

forth between these little plots. However, even though the

traditional farmers produced lower average yields than they would if

they'd just made one big garden, the many plots in different areas

evened out variations in yield due to weather. As a result,

farmers always managed to grow enough to survive and were never faced

with starvation even during bad years.

A similar technique involves moving seasonally. For example, farmers

in

the Alps gather together in the valleys for the winter then

disperse across the mountaintops during the spring and summer. On

the homestead scale, I'd love to one day have an orchard on a ridge top

that's more likely to miss late spring frosts.

A similar technique involves moving seasonally. For example, farmers

in

the Alps gather together in the valleys for the winter then

disperse across the mountaintops during the spring and summer. On

the homestead scale, I'd love to one day have an orchard on a ridge top

that's more likely to miss late spring frosts.

Other methods that traditional societies use to deal with unpredictable

food sources are less relevant to the modern homesteader. We

probably don't want to share all of our food with neighbors to even out

the supply (especially because we can now just dry, freeze, or can

excess for later). Gorging ourselves in the summer so we can live

off body fat during lean times probably won't go into fashion in America

anytime soon, either. But many homesteaders do use the

traditional method of "storing" excess produce by feeding it to livestock, then eating the pigs or other animals in the fall or winter.

Yet another

response to seasonal food shortages is to expand your diet. When

times are hard, people are willing to eat foods that aren't as tasty or

that need special processing to leach out poisons (such as tannin-rich

acorns). Modern homesteaders take a step in this direction when

they learn to love winter kale instead of craving hydroponic tomatoes

during the cold season.

Stay tuned for more lessons we can learn from traditional societies in tomorrow's post.

| This post is part of our The World Until Yesterday lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

These small

space heaters have a message printed in capital letters warning

against using anywhere but an indoor setting.

It only took a couple of

hours of unauthorized space heating focused on the unburied section to

thaw out our wash waterline.

Last spring, I had trouble for the first time with damping off.

This fungal disease is evident when seemingly healthy seedlings die

near where their stems meet the ground. When you're itching for

the first seedlings of the year to push forth their greenery, damping

off can be very traumatic for the gardener. (Okay, maybe that's

just me.)

Last spring, I had trouble for the first time with damping off.

This fungal disease is evident when seemingly healthy seedlings die

near where their stems meet the ground. When you're itching for

the first seedlings of the year to push forth their greenery, damping

off can be very traumatic for the gardener. (Okay, maybe that's

just me.)

Since I was using the same stump dirt

as in previous years, I felt that the issue last year might have been

problematic fungi colonizing my old seed-starting flats. Sure, I

could have bought new flats, but I thought it would be easier (and

definitely cheaper) to simply soak the ones I have in bleach water for

about half an hour. After that, I filled up the flats and seeded

my onions, then made a control flat out of a rotisserie-chicken

container. (Rotisserie chickens seldom come home with us, but we

had a long day in the big city last week and I was too exhausted to

cook, so Mark bought one as a rare treat.)

Hopefully I won't see any

damping off at all, but if I see it in the store-bought flats but not

in the chicken flat, I'll know I was right about the flats being the

problem (and wrong about the bleach water curing it). On the other

hand, if I see damping off in all the flats, I'll know the stump dirt

is the problem and will have to consider one of the mainstream cures ---

either buying real potting soil or sterilizing my stump dirt in the

oven. I like to think the bacteria and fungi in my unsterilized

potting soil are good for baby seedlings, but I could be wrong.

Other possible ways to

deal with damping off include tweaking the environment and using

home-made sprays. The fungi involved like cool, damp conditions,

so if you can warm things up (maybe with a heating pad under the flats)

and keep watering to a minimum, you might be able to whip the bad

microorganisms even if they're present. Some gardeners even make

chamomile or garlic tea and pour it over their potting soil to protect

the seedlings. I'll let you know if I have to resort to any of

those extremes, and if so, which ones work. In the meantime, feel

free to chime in about your battles with damping off in the comments.

The World Until Yesterday

includes an entire chapter on constructive paranoia --- the tendency of

members of traditional societies to assume the worst can happen and to

avoid potentially hazardous situations. I was tickled by this

chapter because Mark applies the same strategy to our farm, although he

calls it "safety first." We have rules like "No one uses a ladder

when they're alone on the farm." The idea is that, even if I would

probably be fine 99 times out 100 when clambering up a ladder, the

100th time could kill me, especially if no one was around to rush me to

the hospital. Similarly, in traditional societies, camping under a

dead tree might be fine most of the time, but why risk it if a tree

fell on your great-uncle and killed him?

The World Until Yesterday

includes an entire chapter on constructive paranoia --- the tendency of

members of traditional societies to assume the worst can happen and to

avoid potentially hazardous situations. I was tickled by this

chapter because Mark applies the same strategy to our farm, although he

calls it "safety first." We have rules like "No one uses a ladder

when they're alone on the farm." The idea is that, even if I would

probably be fine 99 times out 100 when clambering up a ladder, the

100th time could kill me, especially if no one was around to rush me to

the hospital. Similarly, in traditional societies, camping under a

dead tree might be fine most of the time, but why risk it if a tree

fell on your great-uncle and killed him?

Another tip we can take

away from traditional societies is a different way of looking at trade

items. Diamond notes that members of traditional societies trade

for both useful and luxury items even if the communities could have

easily learned how to make the traded-for items on their own. Why

not be self-sufficient if you can be? Diamond's conclusion is that

trade is really about cementing bonds between the traders just as much

as it is about getting something you really need. In fact,

traditional societies often have a time lapse between gifts, so it's

more like you're building social capital by giving a gift than like

you're bartering. Those of us raised in a money-based society may

find this technique odd, but I feel like using social capital to build

relationships is just as valuable in modern societies as it was in

ancient ones.

| This post is part of our The World Until Yesterday lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our drinking water thawed out

today. It's been frozen for weeks.

Just in time to stock up on

back up jugs for this upcoming cold front.

We installed one of those

electric pipe heaters today to the section that's not buried and with

any luck that will keep us unfrozen for the rest of 2014.

Over most of the U.S., the beginning of February is the perfect time to cut scionwood to be grafted onto rootstocks or existing fruit trees later in the spring. So

the first task on my list

for February in recent years has been emailing scionwood swappers who

I've set up deals with earlier in the winter. We share mailing

addresses and reminders of the scionwood we each want to swap.

Over most of the U.S., the beginning of February is the perfect time to cut scionwood to be grafted onto rootstocks or existing fruit trees later in the spring. So

the first task on my list

for February in recent years has been emailing scionwood swappers who

I've set up deals with earlier in the winter. We share mailing

addresses and reminders of the scionwood we each want to swap.

If you don't have anyone to swap with, check out this post about my two favorite website for online scionwood exchange. From hanging out with the North American Scion Exchange group, I've also learned that it's better not

to wrap scionwood in wet newspaper. Instead, just cut fresh

twigs, slip them inside a ziplock bag, and add one drop of water. A

wit over there admonished us that if one drop of water really doesn't

feel like enough...and one more. As for shipping --- a padded

envelope seems to be sufficient, which will cost you less than $3 for

small quantities.

I've

already got a tiny bundle of rare and precious apple scionwood waiting

in the crisper drawer of our fridge for the rootstock to arrive.

The pro who sent it painted beeswax on the cut ends of each twig, then

wrapped the scionwood in plastic wrap. He seemed like an expert if

his extensive list of apple varieties is any indication, so I suspect

his shipping method is also quite effective.

I've

already got a tiny bundle of rare and precious apple scionwood waiting

in the crisper drawer of our fridge for the rootstock to arrive.

The pro who sent it painted beeswax on the cut ends of each twig, then

wrapped the scionwood in plastic wrap. He seemed like an expert if

his extensive list of apple varieties is any indication, so I suspect

his shipping method is also quite effective.

As a side note, I am willing to

swap with newbies who don't have anything I want, but only if you do me

a favor in exchange. The favor usually involves taking a photo of

your experiment so I can share it with future readers. So if

you're interested in a fruit-tree variety you've heard about here, but

don't have an orchard of your own yet, come up with a fun experiment and

email me. Happy swapping!

One

of the biggest differences between traditional societies and the state

societies you and I are more familiar with is how people both inside and

outside tribes are treated. Unlike state societies, where you

make friends based on shared interests, friendships

in traditional societies are based on kinship, marriage, and childhood

geography. All strangers

are potentially dangerous, so when two people meet, they may spend

hours trying to figure out if they have a relative in common.

(Appalachia isn't too far off from this tribal focus on kinship. I

can't count how many times strangers have asked me if I'm related to

the Hesses in Honaker. For the record, the answer is no.)

One

of the biggest differences between traditional societies and the state

societies you and I are more familiar with is how people both inside and

outside tribes are treated. Unlike state societies, where you

make friends based on shared interests, friendships

in traditional societies are based on kinship, marriage, and childhood

geography. All strangers

are potentially dangerous, so when two people meet, they may spend

hours trying to figure out if they have a relative in common.

(Appalachia isn't too far off from this tribal focus on kinship. I

can't count how many times strangers have asked me if I'm related to

the Hesses in Honaker. For the record, the answer is no.)

Another important

distinction between state and traditional societies pertains to how

disputes are resolved. In state societies, the government has

taken away individuals' abilities to resolve major conflicts (vigilante

justice), which is both good and bad. On the positive side, state

societies have lower death tolls since wrongs in traditional societies

often lead to warfare, which tends to go on indefinitely due to

tit-for-tat justice. On the other hand, members of traditional

societies have much more of an incentive to resolve conflict in a way

that leaves everyone happy since the other option is war.

So

how are most conflicts resolved? Unlike the American justice

system, which is based on fairness and guilt, traditional societies

resolve disputes in ways that promote a fast, emotional reconciliation

without an emphasis on right and wrong. The goal is to let the two

parties reestablish their previous relationship so they can live

together peacefully in the future. Diamond suggests that this is

something we should strive to mimic, especially in situations like

disputes between divorcing parents and between siblings arguing over an

inheritance. In modern societies, mediation can yield some of the

same results if done properly.

So

how are most conflicts resolved? Unlike the American justice

system, which is based on fairness and guilt, traditional societies

resolve disputes in ways that promote a fast, emotional reconciliation

without an emphasis on right and wrong. The goal is to let the two

parties reestablish their previous relationship so they can live

together peacefully in the future. Diamond suggests that this is

something we should strive to mimic, especially in situations like

disputes between divorcing parents and between siblings arguing over an

inheritance. In modern societies, mediation can yield some of the

same results if done properly.

Unfortunately, I feel

like many of the social advantages of traditional societies may be

impossible to recapture in our modern world. While I regret living

a distance away from many loved ones, I also wouldn't want to be forced

to settle in town next-door to our family home. I like the way

modern society allows us to be individuals who don't have to cave to

mainstream beliefs, but at the same time, I feel a bit lonely sometimes

when most of my neighbors live in a very different mental world than I

do. Clearly, most of us have been given the choice about whether

to live a more traditional existence, and we've mostly chosen the modern

route instead.

| This post is part of our The World Until Yesterday lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our trusty

trail camera recorded a

deer intruder early this morning.

Anna's gardening intuition

told her the spot where the fence is mushed down was done by an

escaping deer recently.

We upgraded that section with

an additional post and tightened it up. I had turned the mechanical

deer deterrent off the

other night because I didn't want them to get accustomed to the sound.

Maybe turning it back on tonight will spook our intruder enough to

leave for good.

I wonder if it would be

possible to modify a trail camera to send some sort of message when

these events happen? Then maybe I could wake up in enough time to turn

this intruder into dinner...if of course deer season was in.

The photo above shows a

family friend (far left), me and my younger sister in our mother's lap,

my father, and my brother. But if you look closely, you'll see

we're posing in front of...(wait for it)...our brand new outhouse.

My father was probably proud of the structure and chose the spot.

When explaining this photo to me, Mom added, "This is before all the

[poop] started oozing out from behind the plywood...."

I don't remember the marital strife that seems to have been involved in

(not) emptying out the composting toilet, but I do recall sitting inside

for hours. I wasn't constipated; I was reading.

More

photos from the same time period illustrate our rustic farmhouse

kitchen. One of Mom's favorite stories from this time period takes

place here, when a rat, dying from poison, entered the kitchen in

search of water and drank out of my younger sister's potty chair.

And I was wondering why my parents didn't decide the farm life was

fun....

More

photos from the same time period illustrate our rustic farmhouse

kitchen. One of Mom's favorite stories from this time period takes

place here, when a rat, dying from poison, entered the kitchen in

search of water and drank out of my younger sister's potty chair.

And I was wondering why my parents didn't decide the farm life was

fun....

More seriously, Mom

mentions "One knife was handmade...made from a sawblade.... Errol

looks tired...and sweaty...." (If you're keeping track at home,

that's my father and younger sister in the top photo and my brother in

the second photo, in front of a metal bucket we used to heat up water on

the stove.)

This is what I was doing

while all that hard work was happening. If I'd been a year or two

older, I would have had a book in my hand, but I wouldn't have been any

more helpful.

Although I'll leave Diamond's

larger description of religion for you to read about on your own, I did

want to write about one factor that the author believes has made

religion a staple of traditional societies. As I mentioned

previously, it's very important to separate "us" from "them" in

traditional societies since strangers are potentially dangerous, and

religion helps cement that distinction. Religion is usually

expensive either in terms of time or money, so your willingness to jump

through those hoops serves as evidence of your commitment to support

others of your religion.

Although I'll leave Diamond's

larger description of religion for you to read about on your own, I did

want to write about one factor that the author believes has made

religion a staple of traditional societies. As I mentioned

previously, it's very important to separate "us" from "them" in

traditional societies since strangers are potentially dangerous, and

religion helps cement that distinction. Religion is usually

expensive either in terms of time or money, so your willingness to jump

through those hoops serves as evidence of your commitment to support

others of your religion.

Why is this relevant to

homesteaders? Diamond reports that intentional communities are

much more likely to stand the test of time if they're based around a

central religion. One study examined the communes that popped up

in the U.S. in the 1970s and found that secular communities dissolved

four times faster than those with a religious focus. Similarly,

religious kibbutzim in Israel have been much more successful than

secular ones.

That observation reminded me of an interesting series of posts on Club Orlov,

assessing which intentional communities survive and which fail.

Both Diamond and Orlov touch on the success of the Hutterites, a

religious group related to the Amish who live in small agricultural

communities throughout the western U.S. and Canada. It looks like I am Hutterite should move its way up to the top of my reading list.

| This post is part of our The World Until Yesterday lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I moved the trail

camera yesterday and it

proved Anna was right about where the night

time intruder has been

entering our chicken pasture.

The images show her being

startled by the red light activating on the camera, and then moments

later she looks in the direction of the deer deterrent and runs the

other way.

First of all, don't forget that today is your last day to enter our kefir giveaway! Now, on to the real post....

First of all, don't forget that today is your last day to enter our kefir giveaway! Now, on to the real post....

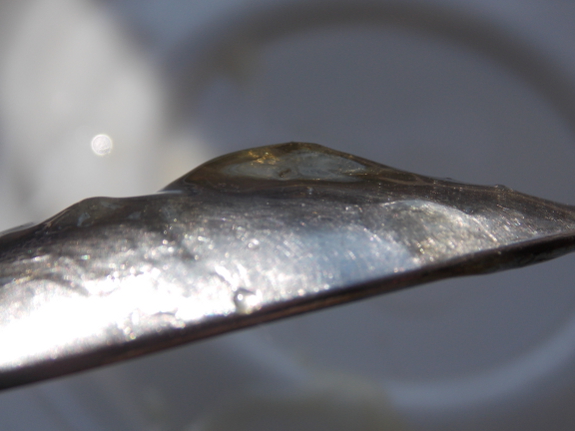

When I started playing with kefir,

I read all of the instructions on the internet that told me to strain

my kefir each day in a plastic sieve (no non-stainless-steel

metal). That allows you to decant the kefir from the grains very

effectively, and is definitely the best way to manage your kefir.

But...we don't have a

plastic sieve. And the primary hunk of kefir grain is so big, it's

quite simple to scoop out of a bowl of kefir. Sure, I might miss

some tiny off-shoots this way, but what has happened so far is that the

main grain puts out a smaller bud, like the one you can see in the photo

above, and I can either cut that off or just notice it's missing and go

scooping around for it when I want to expand my kefir colony. So

far, we've expanded once, and one of the grains is probably about ready

to split again.

While my non-seiving

method is the height of laziness, I can't help thinking that I'm

probably following the lead of the original kefir culturers. Do

you really think the nomadic shepherds in the Middle East who first

developed kefir had plastic sieves and time to let the liquid slowly

drain out of their fermented milk? I could be wrong, but I'll bet

they were scoopers too.

Which

is all a long way of saying --- kefir culture certainly can be simple

if you let it be! Once a day, I put in about five minutes

decanting a jar of fermented milk, scooping out the, grains, refilling

the jar, and (the more time-consuming part) doctoring Mark's kefir so it

tastes like chocolate. I thought I had an iron stomach before we

started, but I've noticed my stomach is even stronger now, without even

the rare bouts of flatulence that sometimes came from eating peanut

butter.

Which

is all a long way of saying --- kefir culture certainly can be simple

if you let it be! Once a day, I put in about five minutes

decanting a jar of fermented milk, scooping out the, grains, refilling

the jar, and (the more time-consuming part) doctoring Mark's kefir so it

tastes like chocolate. I thought I had an iron stomach before we

started, but I've noticed my stomach is even stronger now, without even

the rare bouts of flatulence that sometimes came from eating peanut

butter.

As a side note, kefir

isn't terribly photogenic, so I've included a couple of photos from my

Friday walk in this post. So, don't spend too long trying to

figure out how a hawk and a cracked puddle relate to fermented

milk...but feel free to tell me in the comments if they do.

Anna wanted to see some

pictures of when I was around the age of 5 and my Mom was quick to

reply with these snap shots from the 1970's.

The above photo is from my

third birthday party...just 2 weeks before I was to meet my younger

brother for the first time.

A lot of good memories roasting marshmallows by a campfire. This one is of me around the age of 5 making our own dessert with my brother and cousins. My Mamaw told us more than once that playing in the fire would cause us to pee in the bed that night...I can now confirm she was mistaken and that's just another Mountain Myth.

Chicken bones have been a problem on our farm for years. I like to stew them up to make delicious broth,

but after that, the bones are too brittle to be safely fed to

Lucy. And if we put the bones anywhere except deep

underground...Lucy finds them! Some weeks, I'd decide not to cook

one of our delicious homegrown chickens because I didn't want to deal

with the bones.

But I recently saw on two different blogs where homesteaders were putting their chicken bones in the fire to make biochar.

Great idea! It turns out that if I throw the wet mass of bones

onto a strong fire in our wood stove just before it's time to damp it

down, the bones quickly turn into a crumbly form that I suspect will

have many of the benefits of biochar (with none of the succulent smell

that attracts Lucy). We always sift our wood-stove ashes to

salvage the charcoal for the garden, so the bone char will be put to

good use.

The solution is so

simple, I can't figure out why I didn't think of it before! I

guess I'd better thaw out one of those chickens in the freezer....

I've heard of some organic

chicken growers using a coconut enhanced feed compared to the

conventional product that relies heavily on corn and dreamed up the

hanging coconut chicken treat experiment.

Turns out the chickens

approve of raw coconut, although I think I'll bake the next one to make

the meat easier to chunk away.

Now

that we have both the Avian Aqua Miser and EZ Miser available (plus kit

forms of each), I often get asked --- which chicken waterer is the best

for my situation? This is the time of year when even folks who

don't have chickens...yet...are interested in the answer, so I figured

I'd post the answer here rather than on our chicken blog.

Now

that we have both the Avian Aqua Miser and EZ Miser available (plus kit

forms of each), I often get asked --- which chicken waterer is the best

for my situation? This is the time of year when even folks who

don't have chickens...yet...are interested in the answer, so I figured

I'd post the answer here rather than on our chicken blog.

Our Avian Aqua Miser Original

is my go-to waterer for chicks during their first week of life, for

chickens in a tractor, for broody hens, and for small numbers of birds

in the winter. If you've got a flock of five or fewer hens in your

backyard, you'll love the utility of this little waterer, which stays

perfectly clean due to its hanging nature and is simple to carry inside

on cold nights. Mark's first waterer invention barely takes up any

space, so is perfect for tight spaces, and the Original holds enough

water for up to 25 chicks per day when they're a month or less old.

On the other hand, we prefer EZ Misers

for broilers as they get larger and for farm-size flocks of

layers. With these larger numbers of birds, you're going to have

to allot more space anyway, so having a waterer that sits on a

cinderblock isn't usually a problem. In fact, it's handy to be

able to set EZ Misers out in pastures where no infrastructure exists to

hang a waterer. Plus, the larger capacity of the EZ Miser means

you don't have to fill the waterer as frequently, which is a boon during

busy summer days when you're catering to two flocks of broilers and a

dozen laying hens. Being able to set the EZ Miser down while

filling saves yet more energy.

On the other hand, we prefer EZ Misers

for broilers as they get larger and for farm-size flocks of

layers. With these larger numbers of birds, you're going to have

to allot more space anyway, so having a waterer that sits on a

cinderblock isn't usually a problem. In fact, it's handy to be

able to set EZ Misers out in pastures where no infrastructure exists to

hang a waterer. Plus, the larger capacity of the EZ Miser means

you don't have to fill the waterer as frequently, which is a boon during

busy summer days when you're catering to two flocks of broilers and a

dozen laying hens. Being able to set the EZ Miser down while

filling saves yet more energy.

The kit version of each

is a way to save money, and also allows you to make a waterer that fits

your farm to a T. For example, this video shows how to turn our Avian Aqua Miser Original kits into a heated waterer that's good down to at least 14 degrees Fahrenheit --- that's what we used in our main coop this winter. And our EZ Miser kits

allow you to install watering spouts into the side of just about any

plastic container --- imagine a 55 gallon barrel set in your pasture

with six spouts around the edges for watering over a hundred birds for

days on end. To tempt you to try out one of these scenarios, we've marked our most popular EZ Miser kit down to $36 this week --- enjoy!

I hope this rundown helps

you figure out the perfect waterer for your farm this year. We'll

be starting eggs in our incubator soon and are looking forward to

fluffy spring chicks, so we'll be suiting words to action shortly.

I

hope my newest ebook excites you as much as it does me! This is

the time of year when we all really need some garden porn, and picking

the 81 most informative shots of our permaculture garden for this ebook

was a real treat. Of course, I added in plenty of information too,

from a rundown on the ten worst garden pests in the U.S. to tips on

keeping those (and other) invertebrates at a dull roar without spraying

anything. (You can read the full book description here.)

I

hope my newest ebook excites you as much as it does me! This is

the time of year when we all really need some garden porn, and picking

the 81 most informative shots of our permaculture garden for this ebook

was a real treat. Of course, I added in plenty of information too,

from a rundown on the ten worst garden pests in the U.S. to tips on

keeping those (and other) invertebrates at a dull roar without spraying

anything. (You can read the full book description here.)

Naturally Bug-Free is only $1.99 on Amazon, and if you subscribe to Amazon Prime, you can borrow the title for free. As usual, it's easy to read my ebook on any device even if you don't have a kindle. And, also as usual, I'll be setting the book free this Friday if you can't afford that price tag.

If you enjoy what you read, I hope you'll take a minute to write a

review on Amazon --- those early reviews really help my books reach

beyond the choir. In the meantime, stay tuned for a week of insect-related tips drawn from the pages of Naturally Bug-Free.

| This post is part of our Naturally Bug-Free lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Today was the second time

this Winter we've used the well to fill the tank.

We learned the last time it's

better to drain the hose now while it's easy instead of letting it

freeze solid with a half gallon of water somewhere in the middle.

If previous years are any

indication, the first spring flowers will be opening up within two or

three weeks. To the human eye, hazel flowers probably don't look

like much, but they mean high-protein pollen for our bee colonies to

feed to their young. In fact, if I was unkind enough to open our

hives in this dreary winter weather, I'd probably find eggs being laid

as the queens gear up for spring --- if no eggs now, then soon.

Instead of bothering our bees, though, I just gave both hives a tap.

Sure enough, hearty buzzing met my ear in each, despite the pile of

dead bees in front of the strong hive and the fact that the barn swarm

didn't seem to have enough bees to survive this cold winter.

Perhaps the quilt I added to the top of that Langstroth hive has helped the tiny colony stay warm?

One group of

wholly-positive garden invertebrates is the bugs who consume bad insects.

Spiders, centipedes, dragonflies, mantids (aka praying mantises),

ambush bugs, assassin bugs, lacewings, ladybird beetles (aka ladybugs),

ground beetles, true wasps, digger wasps, hoverflies, and robber flies

all subsist primarily or entirely on other insects during some stage of

their life cycle.

One group of

wholly-positive garden invertebrates is the bugs who consume bad insects.

Spiders, centipedes, dragonflies, mantids (aka praying mantises),

ambush bugs, assassin bugs, lacewings, ladybird beetles (aka ladybugs),

ground beetles, true wasps, digger wasps, hoverflies, and robber flies

all subsist primarily or entirely on other insects during some stage of

their life cycle.

Although many of the species listed above are generalist predators,

eating whatever ends up  in front of them, all of these insects help keep pest population

explosions in check. For example, I accidentally let the beetles

on my green-bean plants get out of control one summer, and soon

thereafter I saw a pair of praying mantises move in to take advantage of

the bounty. Sure, the mantises might have been eating butterflies

yesterday, but I consider them beneficial insects because they eat at least as

many bad bugs as good.

in front of them, all of these insects help keep pest population

explosions in check. For example, I accidentally let the beetles

on my green-bean plants get out of control one summer, and soon

thereafter I saw a pair of praying mantises move in to take advantage of

the bounty. Sure, the mantises might have been eating butterflies

yesterday, but I consider them beneficial insects because they eat at least as

many bad bugs as good.

Many gardeners fall in love with the idea of

predatory and parasitic insects and decide to buy some of these critters

to seed their garden. However, I believe that you really need to

encourage all of these species at the ecosystem level. I've heard

of people opening a container of expensive insects, only to have them

all fly away because the garden isn't a hospitable environment for the predators

to live in.

Many gardeners fall in love with the idea of

predatory and parasitic insects and decide to buy some of these critters

to seed their garden. However, I believe that you really need to

encourage all of these species at the ecosystem level. I've heard

of people opening a container of expensive insects, only to have them

all fly away because the garden isn't a hospitable environment for the predators

to live in.

Instead of spending your money on insects, why not

spend a bit of time encouraging the good bugs you already have to stick

around and reproduce? Many depend on flowers during some stage of

their life cycle, so you can encourage them just like you did native

pollinators by ensuring you have copious pollen and nectar sources available

throughout the growing season.

In fact, you might receive double the benefit

from any nest sites you put out for your native pollinators. Brian

Cooper erected mason-bee blocks in his garden, and ended up encouraging

mud daubers by providing wet mud nearby. Brian wrote: "When we went

to

harvest the bees, we found mud daubers also laid eggs in some of the

unused cells. They collect food for their young inside the cell

before

they cap it with mud. I found one cell that was filled with

caterpillars and a dauber larvae, and another cell with a pupa of the

mud dauber and just bug parts left over."

Weedy edges will also encourage predatory insects

since the predators need to be able to find lots of insects to

eat even when your garden pests are under control. In addition,

dragonflies need a pond into which they can lay their eggs, and many

insects will

benefit from having a very shallow body of water from which they can

drink. When attracting predatory insects, it's imperative not to

use any pesticides (even organic ones) and to allow low levels of pest

insects to fly under your radar. If there aren't any bad bugs

around, your predatory insects won't have anything to eat and will go

somewhere else.

Weedy edges will also encourage predatory insects

since the predators need to be able to find lots of insects to

eat even when your garden pests are under control. In addition,

dragonflies need a pond into which they can lay their eggs, and many

insects will

benefit from having a very shallow body of water from which they can

drink. When attracting predatory insects, it's imperative not to

use any pesticides (even organic ones) and to allow low levels of pest

insects to fly under your radar. If there aren't any bad bugs

around, your predatory insects won't have anything to eat and will go

somewhere else.

In fact, you'll probably sense a theme throughout Naturally Bug-Free. To encourage the good bugs, let nature move into your

garden. Leave things alone and the beneficials will come.

I hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Naturally Bug-Free!

If

so, you can download the ebook for $1.99 on Amazon by clicking the link

above. Or just wait for another excerpt tomorrow on the blog.

| This post is part of our Naturally Bug-Free lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Predictions of 2 feet of snow

prompted Anna to ask me what's the most snow I can remember walking

through and I think a few years in the early 70's created conditions

close to that in Ohio where I grew up.

Today I overheard a

conversation waiting in line at the post office where two older guys

were talking about the Winter of 1947 when the school burned down and

the snow was up to his waist when he was in the First grade.

I remember one of those

Winter days in the early 70's when my Dad took a 2x4 and rolled it in

the snow until it was massive. One of us decided it looked like a whale

and an hour later after much sculpting and a little blue food coloring

we had the only Snow Whale on the block.

We've been on the trail of the rat living under our chicken coop

for a couple of weeks now. While you'd think rats are a cosmetic

problem, they're actually very dangerous as we get close to chick season

since rats can demolish a flock of fuzzy babies in short order.

We've been on the trail of the rat living under our chicken coop

for a couple of weeks now. While you'd think rats are a cosmetic

problem, they're actually very dangerous as we get close to chick season

since rats can demolish a flock of fuzzy babies in short order.

I started trying to catch

the rat while Mark was away visiting his parents in Ohio in

January. I stopped after a couple of failed attempts, though,

because I was afraid of hurting Lucy...and was also afraid of snapping

my fingers in the trap. Mark has a certain calm focus that's very

handy when using chainsaws and setting rat traps, so I let him take care

of round 3.

The good news?

Within two hours, the rat was dead. The bad news? An hour

later, Mark saw another rat. This one wasn't interested in

following its coop-mate's path to the happy hunting grounds in the sky,

so we're back to the drawing board. How to catch a now-trap-shy

rat?

Squash vine borers were our archnemesis during our

early years on the farm, so much so that I even resorted to spraying Bt

on the plants' stems. And I'm glad to say that the Bt didn't

help. Why am I glad? Because if that seemingly innocuous*

spray had proven effective, I might not have figured out less intrusive

ways to keep vine borers in check.

Squash vine borers were our archnemesis during our

early years on the farm, so much so that I even resorted to spraying Bt

on the plants' stems. And I'm glad to say that the Bt didn't

help. Why am I glad? Because if that seemingly innocuous*

spray had proven effective, I might not have figured out less intrusive

ways to keep vine borers in check.

Variety selection was part of my solution, as I'll

explain in a later post, but the biggest reason I started being able

to harvest summer squash is because I learned to succession plant these

speedy vegetables biweekly in the summer garden. Here in zone 6

(last frost: May 15, first frost: October 10), I plant crookneck

(summer) squash on May 1 (a gamble), May 15, June 1, June 15, and July 1

(a slight gamble),

a schedule that allows us to be overwhelmed with tasty squashes despite

heavy vine-borer

pressure and with the use of no other control measures beyond variety selection.

Succession planting is handy with other types of

vegetables as well, although the strategy only works if you choose

varieties that put out a big harvest right away. For example, I

succession plant bush beans rather than growing runner beans since the

former provide lots of green beans before the bean beetles move in to

dine. On the other hand, succession planting wouldn't be a good

choice for tomatoes since even determinate varieties require months of

growth before they ripen their first fruit.

Succession planting is handy with other types of

vegetables as well, although the strategy only works if you choose

varieties that put out a big harvest right away. For example, I

succession plant bush beans rather than growing runner beans since the

former provide lots of green beans before the bean beetles move in to

dine. On the other hand, succession planting wouldn't be a good

choice for tomatoes since even determinate varieties require months of

growth before they ripen their first fruit.

Another benefit of succession planting comes when the

food reaches our table. A few studies have suggested that

cucurbits (and perhaps other vegetables) have more micronutrients on

hand when they mature their first fruits, so the earliest harvest often

tastes best. Some gourmet farmers pull out their squash vines after the first harvest as a

matter of course, figuring it's better to

maximize flavor rather than yield. So maybe the borers are trying

to do me a favor by prompting me to eat the most nutrient-rich and

tasty vegetables possible?

I hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Naturally Bug-Free!

If so, you can download the ebook for $1.99 on Amazon by clicking the

link above. Or just wait for another excerpt tomorrow on the blog.

* The glossary of Naturally Bug-Free suggests some ways in which Bt might not be as safe as many of us think.

| This post is part of our Naturally Bug-Free lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Anna and I sometimes play

this game where she'll ask me "Do you know where those maple syrup

spouts are that we last used 6 years ago?"

It takes me a few seconds to

process the question, and this time my answer was the barn, but the

guessing part comes when she wants to know how long will it take to

find.

Today my guess was under 10

minutes, which turned out to be closer to 5. A small miracle if you

knew just how unorganized our barn is.

What are we using the spouts

for? An experiment to see if bees will eat the sap.

Mark mentioned in his last post that we were thinking of tapping some sugar maples and feeding the sap to bees.

I can't decide whether this is a great idea or a terrible idea, since

both sides of the argument are well represented on the internet.

On the plus side, an 1870 article in American Bee Journal

reports that the author sweetened three quarts of maple sap with a pint

of honey and fed the result to his bees. Various websites also

mention modern observations that honeybees will feed on sap coming out

of gashes in maple bark or from cut stumps if weather is warm enough for

them to fly while sap is flowing.

On

the other hand, other beekeepers warn that maple sap is too high in

solids and will give bees dysentery. At only 1% to 3% sugar, maple

sap has a much lower concentration of sweetness than is found in the

nectars bees prefer (30% and up). At the same time, there are high

concentrations of potassium and calcium in maple sap, which might be

good for the bees...or might make them sick. I'd be particularly

leery of cooking down the maple sap into syrup, since I suspect that

could cause chemical changes that might be bad for the bees.

Instead, I would be more likely to use the sap as the base for making

sugar water for bees.

On

the other hand, other beekeepers warn that maple sap is too high in

solids and will give bees dysentery. At only 1% to 3% sugar, maple

sap has a much lower concentration of sweetness than is found in the

nectars bees prefer (30% and up). At the same time, there are high

concentrations of potassium and calcium in maple sap, which might be

good for the bees...or might make them sick. I'd be particularly

leery of cooking down the maple sap into syrup, since I suspect that

could cause chemical changes that might be bad for the bees.

Instead, I would be more likely to use the sap as the base for making

sugar water for bees.

Why am I thinking of feeding bees at all? The main impetus is our tiny barn swarm colony, which barely had any honey going into the winter

and surely doesn't have much left now. I'm also trying to figure

out a hybrid method between the purely bee-friendly beekeeping I've been

using in recent years, and methods that produce enough honey to allow a

real harvest. My gut feeling is that a round of spring feeding

might boost egg production early enough that we'd get a harvest this

year, without (hopefully) negatively impacting the integrity of the

colony too much. Of course, I could just feed them sugar water,

but the idea of using a free resource from the farm is enticing.

I'd be curious to hear thoughts from beekeepers in the audience.

Would you feed your bees maple sap adulterated with extra sugar?

If you're a natural beekeeper, would you consider feeding your bees in

the spring to boost production?

I learned my next lesson on timing the hard

way. In 2012, periodic cicadas crawled out of the ground and

regaled us with their ocean-like symphony. I was intrigued by the

natural occurrence and enjoyed feeding these protein-rich insects to our

chickens, so at first I thought the periodic cicadas were a boon to our

farm. Then I saw this the damage pictured to the left.

I learned my next lesson on timing the hard

way. In 2012, periodic cicadas crawled out of the ground and

regaled us with their ocean-like symphony. I was intrigued by the

natural occurrence and enjoyed feeding these protein-rich insects to our

chickens, so at first I thought the periodic cicadas were a boon to our

farm. Then I saw this the damage pictured to the left.

It turns out that cicadas lay their eggs in tender

twigs of young trees, and seem to preferentially choose fruiting species

over wild saplings. When the young cicadas hatch from their twig

homes, the nymphs drop to the ground and tunnel down to feed on the

tree's roots. While the root sucking may be a long-term problem,

the real issue is that the nymphs damage fruit-tree twigs so much while

coming out of their eggs that the branches often break off and die.

scarce. Every 13 to 17 years, the periodic

cicadas come out of the ground and provide a feast, but by then, the predator

levels are so low that the majority of the cicadas survive untouched. That's why

we have to get a bit more wily when dealing with these insects—periodic

cicadas have outwitted their natural enemies and we can't count on help

from nature.

scarce. Every 13 to 17 years, the periodic

cicadas come out of the ground and provide a feast, but by then, the predator

levels are so low that the majority of the cicadas survive untouched. That's why

we have to get a bit more wily when dealing with these insects—periodic

cicadas have outwitted their natural enemies and we can't count on help

from nature.

The short-term solution to cicada damage is to net

adult cicadas away from the twigs as soon as you hear periodic cicadas

calling. But smarter orchardists also plan around cicada

cycles. If you go to

http://hydrodictyon.eeb.uconn.edu/projects/cicada/databases/magicicada/magi_search.php,

you can choose your state and county and then find out when periodic

cicadas have emerged in your region recently. Add the appropriate

number of years to those emergence dates and you'll know when the next

brood will be out looking for baby fruit trees.

In a perfect world, you'd plant fruit trees no more

than two years before cicada-emergence dates since cicadas aren't as

interested in older trees. Orchardists also choose not to winter

prune fruit trees during a year when periodic cicadas are due to emerge,

knowing the cicadas will do some of their pruning for them.

That's true permaculture gardening at work!

I hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Naturally Bug-Free!

If so, you can download the ebook for $1.99 on Amazon by clicking the

link above. Or just wait for another excerpt tomorrow on the blog.

| This post is part of our Naturally Bug-Free lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It snowed all night here, but not quite enough to break our snow depth record.

Perhaps

if we lived in a colder climate, I wouldn't love snow so much. As

it is, our farm is in a perfect spot for snow. We see it every

year, but don't get bored of endless white expanses. Good snows

like this one that are packable and deep

come perhaps once a year. So even though the snow plow skipped

our little road Thursday morning, I'm sure the outside world will be

scraped and clear by Monday at least.

Perhaps

if we lived in a colder climate, I wouldn't love snow so much. As

it is, our farm is in a perfect spot for snow. We see it every

year, but don't get bored of endless white expanses. Good snows

like this one that are packable and deep

come perhaps once a year. So even though the snow plow skipped

our little road Thursday morning, I'm sure the outside world will be

scraped and clear by Monday at least.

Sure, snow makes a little

extra work on the farm, but not much. I went out this morning to

sweep off the quick hoops and bee-hive entrances. The quick hoops

were mostly in good shape, although I did damage the fabric a bit with

the broom before I got a good handle on how to leave a tiny layer of

snow behind to protect the cloth. The one quick hoop made of  smaller PVC pipes bowed a little under the weight, but sprang back into shape post-sweeping.

smaller PVC pipes bowed a little under the weight, but sprang back into shape post-sweeping.

Our chickens generally

stay in during snowy weather. Mark is a good farmer who almost

always remembers to toss a tarp over the chicken tractor

before a snow, so they have a bit of bare ground to explore. I

think they spend the day napping, though, and waiting for it to be over.

Once my chores were done,

I stole half an hour to make a garden-spirit snow woman. Oregano,

echinacea, red raspberry, and fig detritus gave her some character,

along with a homegrown carrot. Maybe she'll give us a boost for

the upcoming gardening season.

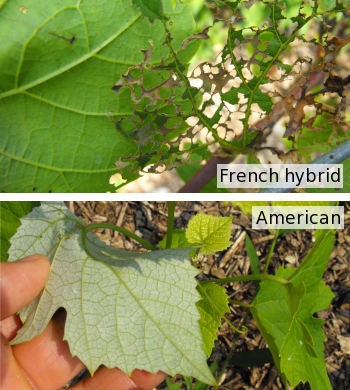

Japanese beetles taught me my first lesson about

variety selection. We had a terrible problem with these invasive

beetles on our grapevines until I realized that French hybrid varieties

are much more tasty to Japanese beetles than are American

varieties. The latter can be distinguished by their thicker

leaves, which are often whitened underneath, and by the relative paucity

of beetles chowing down on the leaves.

Japanese beetles taught me my first lesson about

variety selection. We had a terrible problem with these invasive

beetles on our grapevines until I realized that French hybrid varieties

are much more tasty to Japanese beetles than are American

varieties. The latter can be distinguished by their thicker

leaves, which are often whitened underneath, and by the relative paucity

of beetles chowing down on the leaves.

In addition to grapes,

Japanese beetles also defoliated our young sweet-cherry tree, but damage

on other plants seemed to stay at low enough levels that the trees

could shrug it off. After switching our small vineyard over to

American grapes and removing our cherry tree, the Japanese beetle

pressure was reduced to the point where hand-picking was sufficient to

keep beetles at bay.

In general, variety selection can be a helpful

strategy in controlling at least five of the dirty-dozen worst garden

pests in the U.S. The table below includes pest-resistant

varieties drawn from several different extension-service websites and

other sources.

| Pest insect |

Insect-resistant varieties |

| Cabbageworms |

Collards, Brussels

sprouts, broccoli, and cabbage are tastier to these insects than are

other crucifers. Within each type of vegetable, vegetables with

dark green, glossy leaves are more resistant to cabbageworms, while

cabbage butterflies sometimes avoid laying eggs on red cabbage

varieties. Resistant cabbage varieties include Chieftan Savoy,

Early Globe, Mommoth, Red Acre, Red Rock, Round Dutch, and Savoy

Perfection Drumhead. |

| Corn earworms |

Any corn with a tight husk will

be more resistant to earworms. Specifically resistant varieties

include Country Gentlemen, Golden Security, Seneca, Silvergent, and Staygold. |

| Cucumber beetles |

In general, cucumber beetles

prefer zucchini-type squash over others and don't like burpless

cucumbers as well as other varieties. Blue Hubbard squash, Ashley,

Chipper, Gemini, Piccadilly, Poinsett, and Stono cucumbers; Early

Prolific, Scallop, Straightneck, and White Bush squash; and

Galia, Passport, Pulsar, Rising Star, and Super Star melons are all

reported to be resistant to cucumber beetles. However, the more important issue is to select a variety resistant to the bacterial wilt carried by cucumber beetles. These wilt-resistant varieties include Connecticut Yellow Field, Harvest Moon, and Howden pumpkins; Waltham butternut; Buttercup squash; Black Beauty zucchini; and Ashley, Chinese Long, Chipper, County Fair, Eversweet, Gemini, Improved Long Green, Saticoy Hybrid, Sunnybrook, and Tokio Long cucumbers. Watermelons are usually resistant to bacterial wilt. |

| Squash bugs |

Squash bugs prefer yellow summer

squash over zucchinis, squash over pumpkins, pumpkins over gourds, and

gourds over melons. Resistant varieties include acorn squash,

butternuts, Early Summer Crookneck, Green Striped Cushaw, Improved Green

Hubbard, Spaghetti, Sweet Cheese, and zucchinis (except for the

susceptible Cocozelle). |

| Squash vine borers |

Varieties resistant to squash

vine borers tend to have thin, tough stems. In addition, vining

types are more resistant than bush types since the former can root along

their nodes and survive moderate levels of borer damage. The most

resistant varieties include butternuts and Green Striped Cushaw,

followed by Dickenson Pumpkin and Summer Crookneck. Other

varieties reputed to have at least some resistance include acorn squash,

Cucuzzi (also known as snake gourd), and Connecticut Field, Dickenson,

and Small Summer pumpkins. |

I hope you enjoyed this excerpt from Naturally Bug-Free!

If so, you can download the ebook for free on Amazon by clicking the link above today. Or drop me an email to receive a pdf copy instead. Thanks for reading, and don't forget to leave a review when you're done!

| This post is part of our Naturally Bug-Free lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

How are the girls in the

chicken tractor fairing during all this snow?

They might be bored having to

stay in the same spot 2 days in a row, but they seem perkier and more

content than the main flock.

Outside, I've had to

admit that our garden is more of a zone 5 garden than a zone 6 garden

this year. That means we don't have anything fresh coming in

except Egyptian onion bulbs, and I'm pushing back my earliest plantings

of lettuce, peas, and poppies until the warm spell next week.

Inside, though, our baby onions are growing like gangbusters. So far, all three flats

are acting the same, although the one closest to the wood stove grows

fastest. When I pointed out the adorable little seedlings to Mark,

he replied, "I can't remember the last time I bought an onion."

It's looking more and more like this will be the year we hit onion independence!

It's been a full year since I

shored up this broken

walnut fence post.

I'll use this method again to

fix a few more fence problems.

People

in our neck of the woods know what porches should be used for in the

winter --- firewood storage. Mark and I like to split and stack at

least a week's worth of firewood to sit on the edge of the porch for

easy access to the trailer, and you can tell we're on the upswing of the

season when the pile gets higher every week rather than lower. We

split the same amount of wood, but burn less.

People

in our neck of the woods know what porches should be used for in the

winter --- firewood storage. Mark and I like to split and stack at

least a week's worth of firewood to sit on the edge of the porch for

easy access to the trailer, and you can tell we're on the upswing of the

season when the pile gets higher every week rather than lower. We

split the same amount of wood, but burn less.

The woodshed, on the other hand, is starting to look pretty sparse. But now that the subzero weather

appears to be behind us, I know we'll definitely have enough of the

good dry wood to last at least until March. If previous years are

any indication, firewood will become more of a treat than a necessity

then, with warmer days heating up the trailer via our south-facing banks

of windows and with weekly lows rarely dipping below the twenties.

In fact, next week is supposed to look a lot like March, but my weather

guru tells us not to get too excited. He forecasts at least one

more cold snap before February is out. Maybe that will be the

impetus we need to start getting in next year's firewood sooner rather

than later.

While developing our new EZ Miser 2 gallon

chicken watering bucket I

got into a habit of leaving a full bucket handy to make it easier to

test each variation.

Turns out it's just the right

height for Huckleberry to drink from, and he seems to

drink more water because of it so we've decided to leave it in place to

further spoil him.

Maybe drinking in this

fashion is easier on a cat's back?

Our first eggs of the season are in the incubator! In 21 days, we'll have new chicks to spice up the farm, and our chicken year will be off to its exciting start. Here are my ten top tips for those of you new to chicken incubation.

Our first eggs of the season are in the incubator! In 21 days, we'll have new chicks to spice up the farm, and our chicken year will be off to its exciting start. Here are my ten top tips for those of you new to chicken incubation.

1. Start with quality eggs. Old hens, old eggs, dirty eggs, and bad nutrition are all recipes for heartbreak.

2. Figure out dry incubation.

Depending on your climate, it may be appropriate to follow the

manufacturer's instructions about how much water to put in your

incubator. But it might not.

3. Tape the plug and plan for power outages.

Those tiny chicks growing inside their shells can't stand cooling down,

so make sure there's no way you can accidentally unplug your incubator

or turner. If you live in an area with periodic outages like we

do, you'll also want to figure out what you're going to do if the

electricity goes out for a couple of days in the middle of your

incubation run.

4. Mark the dates on your planner.

18 days after you start your incubator, it's time to unplug the turner

and increase the humidity. 21 days after you start your incubator,

chicks will start hatching.

5. Number your eggs.

This isn't entirely necessary, but good data can help you make each

incubation run a little better than the last. I write a number on

the large end of each egg in pencil, and record the likely mother, date

collected, and whether the egg has any dirt on it.

5. Number your eggs.

This isn't entirely necessary, but good data can help you make each

incubation run a little better than the last. I write a number on

the large end of each egg in pencil, and record the likely mother, date

collected, and whether the egg has any dirt on it.

6. Hang out for the hatch.

Again, this is a bit obsessive, but I like to record the time when each

egg pips (the chick first breaks through the shell). That piece

of data lets me keep an eye on the hatch and make sure that pipped eggs

haven't been rolled upside down by their early-hatching brethren, and

that individual chicks haven't been struggling in the egg for too long.

7. Remove each chick as soon as it's dry.

Some experts recommend leaving the chicks in the incubator for up to 24

hours, but the chicks' chirping says they're much happier if removed to

the brooder as soon as their feathers completely dry off. They're

less likely to harm hatching siblings this way too.

8. Decide whether you're going to help chicks out of the egg. There are major pros and cons of helping chicks, which you can read about here.

The biggest con is that if you help a chick and it's too handicapped to

make it in the flock, you will have to euthanize it. On the other

hand, if a chick is simply pipping at the wrong end of the egg, you can

sometimes help the chick hatch and have it grow up into a happy hen.

9. Prepare the indoor brooder. A rubbermaid bin is a good starter home for your chicks and we use

Brinsea's EcoGlow Chick Brooder to keep our chicks warm

for their first month. You'll also need to buy or make a small feeder for their first few days of life, and will want an Avian Aqua Miser Original for water.

10. Prepare the outdoor brooder.

If you're like me, you'll get sick of the noise and smell of chicks in

your living room after about a week. So you'll want a place close

to the house where they can stay warm and dry but be out of your

hair. The outdoor brooder also allows you to put chicks out on

pasture by the time they're a week old if the weather cooperates.

If this post got you excited and you want to learn more, I highly recommend my ebook Permaculture Chicken: Incubation Handbook for further information. Starting with eggs is definitely

a bit more work than buying mail-order chicks, but the skill opens new

doors for chicken-keepers and is also an inspiring process to

watch. And even if you pay for top-of-the-line equipment like we

did, hatching your own eggs will pay for itself after a few years.

Have fun!

Today was perfect weather for