archives for 12/2013

If you waited to get your homesteading calendar, you're in luck --- they're 50% off this week! Jayne called this a Cyber Monday sale, but I talked her into giving you seven days to make your decision. After all, I know that a lot of homesteaders don't hit the computer every day, and I don't want our loyal readers to miss the opportunity. But be sure to place your order by Saturday night, at which point the calendars will go back up to full price.

I could glow about the awesome job Jayne did on this calendar, but instead, I'll share the words of other readers:

"It is gorgeous! I encourage this for a gift to yourself or a gift to someone who loves good photography of happy homesteading." --- Julie

Enjoy!

We had a busted water pipe

yesterday that turned out to be easy to fix.

A long term solution might be

one of those electric

pipe heaters.

Rosalind Creasy's The Complete Book of Edible Landscaping

was probably a cutting-edge book when it first came out in 1982, but

now I feel like the same information is presented in a better fashion in

various forest gardening books and in Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining Your Edible Landscape Naturally.

The most helpful two-thirds of Creasy's text consists of an

encyclopedia of plants recommended for edible landscaping and, again, I

feel like you'd get more information on that topic from Lee Reich's Uncommon Fruits Worthy of Attention and from Eric Toensmeier's Perennial Vegetables.

Rosalind Creasy's The Complete Book of Edible Landscaping

was probably a cutting-edge book when it first came out in 1982, but

now I feel like the same information is presented in a better fashion in

various forest gardening books and in Robert Kourik's Designing and Maintaining Your Edible Landscape Naturally.

The most helpful two-thirds of Creasy's text consists of an

encyclopedia of plants recommended for edible landscaping and, again, I

feel like you'd get more information on that topic from Lee Reich's Uncommon Fruits Worthy of Attention and from Eric Toensmeier's Perennial Vegetables.

However, Creasy's book is

still worth reading, particularly if you're an urban gardener who has

to make your tomatoes and cabbages blend in with the neighbor's perfect

lawn and clipped hedges. Creasy lists varieties of each species

that are not only productive, but that also are particularly pretty in

the landscape (although some of these varieties have fallen out of

favor and may now be hard to find).

And I should add the caveat that there is an updated version of Rosalind Creasy's book available, although there's no search-inside-the-book feature on Amazon, so I can't tell how much the  book

was revised and now much of the information stayed the same. I

also still mined quite a few thought-provoking tidbits from The Complete Book of Edible Landscaping,

despite having read many of the more-modern books on this theme.

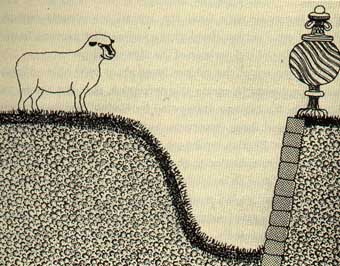

For example, I'd heard of ha-has, but didn't realize that they were

originally imagined as a hidden barrier to keep deer, cattle, and sheep

in sight but out of the garden. And I'd never considered making

low-tech permeable paving similar to the way we built our ford,

by sinking cinderblocks in the ground and filling them with

gravel. Finally, Creasy's book got me thinking more scientifically

about summer shade and winter heat retention around our south-facing

bank of windows...but that's fodder for another post.

book

was revised and now much of the information stayed the same. I

also still mined quite a few thought-provoking tidbits from The Complete Book of Edible Landscaping,

despite having read many of the more-modern books on this theme.

For example, I'd heard of ha-has, but didn't realize that they were

originally imagined as a hidden barrier to keep deer, cattle, and sheep

in sight but out of the garden. And I'd never considered making

low-tech permeable paving similar to the way we built our ford,

by sinking cinderblocks in the ground and filling them with

gravel. Finally, Creasy's book got me thinking more scientifically

about summer shade and winter heat retention around our south-facing

bank of windows...but that's fodder for another post.

Will a chicken eat a crawdad?

That depends...I've seen some

chickens run away after being pinched, but today I gave one to our

White Leghorn and she went crazy for it.

We might think about breeding

them for chicken food in the future or figure out a way to trap them

from our wild population.

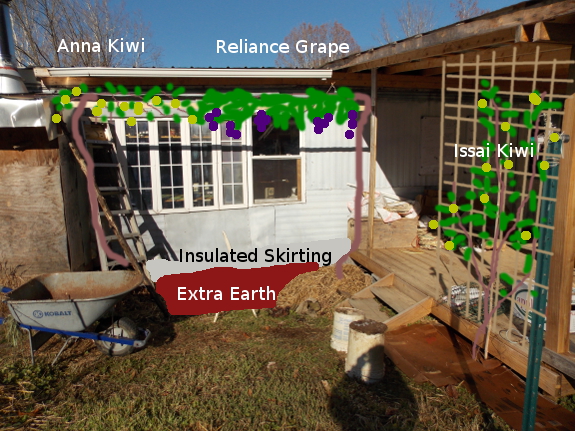

I mentioned in yesterday's post that The Complete Book of Edible Landscaping got me  thinking

in more depth about what we want to do in front of our bank of

south-facing windows. These windows do a remarkable job of heating

the trailer on sunny winter days, but, unfortunately, they do nearly as

good of a job of heating the trailer on sunny summer

days. In a perfect world, we'd plant a big shade tree here, but

that would block out light to my vegetable garden, so I'm instead using

vines on an arbor to reflect the summer heat while letting in winter

sun.

thinking

in more depth about what we want to do in front of our bank of

south-facing windows. These windows do a remarkable job of heating

the trailer on sunny winter days, but, unfortunately, they do nearly as

good of a job of heating the trailer on sunny summer

days. In a perfect world, we'd plant a big shade tree here, but

that would block out light to my vegetable garden, so I'm instead using

vines on an arbor to reflect the summer heat while letting in winter

sun.

This spring, I tried out version 1.0

using a simple pea trellis and scarlet runner beans (shown to the

right). I'm glad of the experiment because it proved to me that

this area is way too waterlogged to plant directly into the

ground. In preparation for version 2.0, Kayla and I dumped weeds

in front of the trailer all summer, and by November, I had some great

topsoil to shovel up into two mounds, one on each side of the row of

windows.

This picture shows what I

imagine the area will look like in five years if everything goes

according to plan. I've already put in the Issai kiwi (this

summer) and the Reliance grape (last month), and the Anna kiwi will be

arriving this spring. The last two were planted in those mounds I

mentioned, and Mark pointed out that we have some good soil that needs

to be excavated near the goat path, which will allow me to fill in

between the two mounds for later root development. I also plan to

finally install the downspout to channel that area's roof water into the

greywater wetland, and Mark's going to upgrade the trellis he started

to make it strong enough to handle two heavy vines, while also making a

lattice on the edge of the porch for the Issai kiwi. (I think

we'll also make the trellis a little higher since the photos above

illustrate how the current height will still shade the windows quite a

bit in the winter.)

The part I haven't

decided yet doesn't actually have anything to do with the plant life,

although it does relate to trailer temperature modification.

Eventually, we want to skirt the whole trailer, but that's a long-term

project that hasn't made it onto the to-do list yet. In the

meantime, I figured we'd better skirt this one little area now before I

start mounding up earth and planting long-lived perennials. I

found several interesting websites while researching the skirting topic

and discovered that there are at least two schools of thought on how to

moderate the floor temperature of a trailer:

- Use plain skirting around the outsides, then lay down a vapor

barrier on the ground under the trailer with polystyrene foam over

top. This is recommended by the extension service in Alaska.

Related alternatives involve blowing foam insulation into the belly

(area between the frame and ground inside the skirting) or making a

false floor below the frame to hold insulation right up against the

underside of your floor.

- Make your own insulated skirting around the perimeter of the trailer using polystyrene foam attached to treated two-by-fours on the ground and to the bottom of the trailer. This option is usually then covered by traditional skirting or paneling of some kind on the outside. No one talks about this, but it seems like you might get better results if you buried the bottom of the insulated skirting a foot or so into the soil?

In Trailersteading (free today!), one of our readers

skirted his home with the insulated centers cut out of doors before

installing windows (shown to the right). That sounds like the

optimal skirting material, but I'm afraid we don't have a source

here. Any other ideas or feelings on which of the two skirting

options above makes the most sense?

In Trailersteading (free today!), one of our readers

skirted his home with the insulated centers cut out of doors before

installing windows (shown to the right). That sounds like the

optimal skirting material, but I'm afraid we don't have a source

here. Any other ideas or feelings on which of the two skirting

options above makes the most sense?

Finally, I'm considering the

utility of stones or cinderblocks used as thermal mass in this

area. Hardy kiwis are damaged by late-spring frosts in our area

and grapes tend to succumb to fungal diseases during our wet summers, so

I figure both plants would enjoy some extra heat gained by covering the

ground with stones between their feet. Rosalind Creasy agreed,

noting that a patio in front of the south-facing wall of our house can

even help heat the home by radiating heat during winter nights (assuming

you can shade the stones enough in the summer so they don't bake you

then). Which brings me to question number two --- would I be

better off using cinder blocks instead of traditional skirting in this

one zone of the trailer to provide yet more thermal mass?

Anyone who made it through this long post ---

you deserve a gold star! Here's your bonus --- did you know that

evergreen shrubs and vines up against the north side of a house can act

as exterior insulation, producing a pocket of air that makes your house

stay warmer? And did you know that I'll be able to guess how much

our trellis will shade the windows in the summer by going out at

midnight under a winter full moon --- the moon shadows will mimic sun

shadows six months later. Tips courtesy of Rosalind Creasy.

You would have thought Anna was playing Agricola from the big smile on her face when she got to try out our neighbor's corn sheller.

She explained that she grew up shelling corn by grabbing a cob with two hands and twisting in opposite directions.

The sheller made short work of this weevily corn, which will give our chickens supplemental carbs this winter.

I left you hanging in yesterday's post

about our skirting decision, and while your thoughtful comments were

pouring in, I went outside to start experimenting. Mark had bought

me a four-foot-by-eight-foot-by-two-inch sheet of rigid-foam

insulation, unfaced because we wanted to buy from our local hardware

store (even though the options there are rather limited) rather than

driving an hour to Lowes. It turned out to be simple to cut the

insulation sheet to size with our hand saw

(much easier than using the utility knife I tried first). Digging

out a little bit of dirt where the insulation was going to go made it

relatively easy to slide the cut pieces into place.

I left you hanging in yesterday's post

about our skirting decision, and while your thoughtful comments were

pouring in, I went outside to start experimenting. Mark had bought

me a four-foot-by-eight-foot-by-two-inch sheet of rigid-foam

insulation, unfaced because we wanted to buy from our local hardware

store (even though the options there are rather limited) rather than

driving an hour to Lowes. It turned out to be simple to cut the

insulation sheet to size with our hand saw

(much easier than using the utility knife I tried first). Digging

out a little bit of dirt where the insulation was going to go made it

relatively easy to slide the cut pieces into place.

From

my perusal of the internet before beginning, I'd thought I'd need to

make a bottom rail for the insulation to attach to and to use button

nails to attach the top of the insulation to the underside of the

trailer. But once I got the insulation wedged into place, it

became clear it wasn't going anywhere, so I skipped that step. I

did use a bit of scrap wood to push one piece back so it lined up with

the other, though.

From

my perusal of the internet before beginning, I'd thought I'd need to

make a bottom rail for the insulation to attach to and to use button

nails to attach the top of the insulation to the underside of the

trailer. But once I got the insulation wedged into place, it

became clear it wasn't going anywhere, so I skipped that step. I

did use a bit of scrap wood to push one piece back so it lined up with

the other, though.

The corrugated pipe we're using to send water from our (as-yet-hypothetical) downspout to our greywater wetland

goes under the trailer, and I'd originally planned to cut a hole in the

insulation to let the pipe through. But as I worked, I figured it

would be simpler to dig down a bit and send the pipe underneath (as you

can see in the photo below). As I type this, though, I'm

wondering if that's a good idea, since the pipe will go down and then

slightly up, meaning a bit of water will pool in the lowest point and

will probably freeze in the winter. I guess we'll wait and see if

that's an issue, or maybe I'll fix the problem before Mark installs the

downspout.

You'll notice there are a

few small cracks between the sheets of foam in the photo above. I

went back and forth on these, at first thinking I'd seal them with

reflective tape, but then realizing that the flashing I planned on

putting on the outside would do the same job. When I finally crawl

underneath to deal with the problematic insulation under the floor (one

of these days...), I may use some spray-foam insulation to fill in

these gaps.

Rigid-foam insulation

isn't supposed to deal well with either UV damage or water, so it needs

some kind of outer layer. We could have bought skirting made for

trailers, but flashing is so easy to work with (and is always on hand),

so I decided to give that a try instead. After I took this photo, I

backfilled some earth around the base (and will add even more dirt

later to increase the height of the planting bed), so the gap at the

bottom shown in the photo above is already long gone.

This small part of the

skirting project was so fun and easy, it made me wonder why we've been

putting off skirting for so long. Then I remembered that I want to

replace the disintegrating insulation under the trailer floor before we

make it even harder to work under there by closing the space in.

We may need to bite the bullet and do that before summer, though, since

the back of the insulation sheets I installed this week are currently

exposed under the trailer, and free-range chicks adore pecking at

styrofoam....

We installed a downspout, but

realized afterward that it's on the wrong side.

The spot where the old farmhouse

used to sit has been earmarked for years as the future site of an

experimental nursery, but this was the first year we planted into the

area. Mark started reclaiming the spot about a year ago, a process

that involved of lots of weedeating to kill off blackberries and

honeysuckle, plus digging out huge poke stumps. Last fall, I

kill-mulched one bed on the side closest to the trailer, using double my

usual thickness of cardboard (two layers instead of one), and that bed

still came up in blackberries and was a problem over the summer.

So I decided to lower my standards and dig out all the roots in that and

another new bed instead of kill mulching for next year.

The spot where the old farmhouse

used to sit has been earmarked for years as the future site of an

experimental nursery, but this was the first year we planted into the

area. Mark started reclaiming the spot about a year ago, a process

that involved of lots of weedeating to kill off blackberries and

honeysuckle, plus digging out huge poke stumps. Last fall, I

kill-mulched one bed on the side closest to the trailer, using double my

usual thickness of cardboard (two layers instead of one), and that bed

still came up in blackberries and was a problem over the summer.

So I decided to lower my standards and dig out all the roots in that and

another new bed instead of kill mulching for next year.

And I'm glad I did! After a week of Thanksgiving eating and writing, shoveling

really hit the spot. I've decided the biggest problem with

no-till gardening is that you don't get to dig often, and I love to dig,

so projects like this make my day.

And I'm glad I did! After a week of Thanksgiving eating and writing, shoveling

really hit the spot. I've decided the biggest problem with

no-till gardening is that you don't get to dig often, and I love to dig,

so projects like this make my day.

But it was also good to

dig that area for more serious reasons. There were lots of big

roots, including one blackberry root mass about the size of a

four-year-old fruit tree, so I suspect it would have taken at least two

more years of mowing before a kill mulch in that area would take.

Plus, the Appalachian foundation of piled up rocks means Kayla and I

disinterred more stones during our digging project than Mark and I have

found during the entire rest  of our time on the farm. The timing was perfect since I want rocks to use around my new grape and didn't have any on hand.

of our time on the farm. The timing was perfect since I want rocks to use around my new grape and didn't have any on hand.

And then there's the pure

pleasure of finding ancient possessions in the soil around an old home

site. Sure, most of what we found was broken window glass and

rusty nails, but Kayla went home with two nice marbles and a little

ceramic container that looked like it might have held makeup or

ointment. And I found a rusty coin from 1951, probably not worth

much, but fascinating for the notion that it was being held in someone's

hand sixty years ago. I think the second picture from the top

might be an old whetstone too?

If I get industrious

again, we've got about three more beds we could dig out in the old house

area, but since I've got other digging projects on the front burner, I

might let Mark mow those areas for another year first. Either way,

it's exciting to have two long beds to fill with experimental

perennials --- more on that in a later post.

Our White Leghorn hen

who likes to eat crayfish

had a close call this week.

A hawk tried to swoop down

and take her away, but once Lucy heard the noise our rooster was making

from the other side of the fence she ran to the scene with enough

aggressive barking to scare the predator away.

Ever since I read the apple chapter in The Botany of Desire,

I've wanted to plant some apple seeds and see if my toss of the dice

turns up a new variety worth keeping. What held me back then was

that I didn't have any land to plant on. And after we got our farm,

I figured I'd have to set aside an absurd amount of space for the

experiment since each tree would be a standard apple, meaning they'd

need to be planted at least 30 feet apart.

Ever since I read the apple chapter in The Botany of Desire,

I've wanted to plant some apple seeds and see if my toss of the dice

turns up a new variety worth keeping. What held me back then was

that I didn't have any land to plant on. And after we got our farm,

I figured I'd have to set aside an absurd amount of space for the

experiment since each tree would be a standard apple, meaning they'd

need to be planted at least 30 feet apart.

But then I started playing with high-density methods,

and learned that judicious pruning and training can make even large

trees small. So I started pondering --- could I plant seeds three

feet apart as if I were making a high-density apple planting, then use

that test orchard to try out seedling genetics? Presumably, it

might still be five or more years before I'd get a taste of these

experimental trees, but that still gives me time for many apple

generations in my lifetime. And if any of the seedling apples are

worth experimenting with further, I can either transplant the tree or

graft its scionwood onto a smaller rootstock. Worst case scenario,

I get a lot of firewood out of the deal.

The

pros tend to plant somewhere between 10,000 and 50,000 seeds to get one

variety worth keeping, and I'd definitely plant many, many fewer.

But it's more fun that going to Vegas --- my kind of gambling.

Want to play?

The

pros tend to plant somewhere between 10,000 and 50,000 seeds to get one

variety worth keeping, and I'd definitely plant many, many fewer.

But it's more fun that going to Vegas --- my kind of gambling.

Want to play?

I'm looking for some

interesting seeds to start my planting, and I promise to name the new

variety after you if you're the source of the seeds. Drop me an email

if you're interested with the name of the mother variety and the

possible fathers (other apple trees close to your tree). I'm

less interested in store-bought apples because the father in that case

is often a crabapple, included in the planting to fertilize the named

varieties, and I'm most interested in off-spring of these disease-resistant apple varieties.

Or you can play along at

home! Here's what I plan to do --- put each batch of cleaned apple

seeds in a labeled ziplock bag surrounded by a damp rag (or paper towel

if you roll that way). Apple seeds need at least a month of cold stratification, so the bag will go in the  fridge,

and I'll start checking on it weekly after the month is up. Once I

start to see sprouts, I'll transfer the seeds to a pot, and then,

eventually, to a nursery row.

Alternatively, you can get the same stratification effect by planting

your seeds directly in the ground right now, allowing them to go through

a normal winter. Either way, expect only about 30% germination,

so plant lots of seeds.

fridge,

and I'll start checking on it weekly after the month is up. Once I

start to see sprouts, I'll transfer the seeds to a pot, and then,

eventually, to a nursery row.

Alternatively, you can get the same stratification effect by planting

your seeds directly in the ground right now, allowing them to go through

a normal winter. Either way, expect only about 30% germination,

so plant lots of seeds.

As a final side note, if

you've got the space for standard trees, you might plant seeds for

another reason --- to serve as rootstocks to be grafted onto. Many

people will plant a dozen or more seeds where they want the eventual

tree to grow, then will weed out all but the most vigorous specimen a

year later. After grafting, these experimenters get a tree with no

transplant shock. Although I've never heard anyone else say this,

it seems to me you could also get at least a little bit of dwarfing

action from seedling rootstocks if you choose seeds from less vigorous

varieties (like crabapples, self-pollinated Cox's Orange Pippin, Lady, and spur-type Winter Banana and York), or if you choose the least

vigorous seedling when it comes time to weed out your planting.

I'd be very curious to hear from anyone who's used seedlings as

rootstocks --- how did your trees turn out?

(As a final note, these photos aren't mine --- as usual, click to see the source.)

When we first got chickens

Lucy was a lot younger and very excited about these new feathered

friends we were introducing to the farm.

It took about 10 minutes to

train Lucy to leave all the chickens alone.

We put her on a leash, walked

her over to a chicken in a tractor and made her sit with her back

facing the tractor. She was excited and kept looking over at the

chicken, but each time I would bring her attention back to me while at

the same time saying with as much authority as I could muster "Our

chickens!.." This went on for about 10 minutes before she seemed to

figure it out and stopped being curious about the chickens.

I think walking her everyday

also helps to anchor the training, but the lesson was taken directly

out of Cesar Millan's book called "Cesar's Way", which might be the best

dog training book available at this time.

It turns out that Rhonda is on the right track --- the gutters on our

roof would have been installed correctly if the whole trailer didn't

tilt

toward the west. It started raining, so we haven't finished the

project yet, but I think we're going to first try taking out the screws

that attach the gutter to the side of the roof, then will give the

gutter more of a

tilt, if possible, so we can keep the downspout where it is.

Worst-case scenario, we'll move the downspout to the other end.

Interestingly, in a heavy rain Friday morning, I noticed that the

downspout seemed to be working pretty well despite the incorrect

tilt. Sure, a bit of water was drizzling out the other end, but

most of the roof runoff appeared to be going down the downspout and into

the greywater wetland, which seemed well able to handle the extra water.

On the downside, it turns out that the high groundwater in that spot

isn't entirely due to water pouring off the trailer roof right

there. Even with that rain being captured by the downspout, water

was pooling right at the surface, meaning I need to keep working if I

don't want the grape and kiwi I'll be installing there to drown.

I'm hoping the extra water comes from the other downspout twelve feet

uphill which spits out water falling on the front porch, but I haven't

quite decided if there's a solution short of channeling that water into

the greywater wetland too. I'd like to have a rain barrel at the

corner of the porch to make watering seedlings easier in the summer, but

we get so much rain that the barrel would do no good in the winter.

Finally, just for fun, I

piled up lots of rocks around the kiwi and grape mounds. Hopefully

these will act as thermal mass and they'll definitely make the plants

more visible so they won't accidentally get weedeaten. And we're

also thinking of taking Brian's advice

and making the trellis out of wire since he makes an excellent point

about the shade potential of lumber. I can't wait to see this area

in full greenery in summer 2014!

It's been a year since I

talked about problems

with one of our chicken coops.

The new double nesting box

has helped with egg access, but I think I could've got away with just

one nest because the days I've noticed both nest boxes being used was

maybe twice.

If all goes as planned, you'll get to read Watermelon Summer, my first young-adult novel,

in about a week. The title is courtesy of my father, who also

talked me out of my last-minute jitters and told me the third draft was

ready to fly. (After it gets back from the copy-editor, that

is.)

If all goes as planned, you'll get to read Watermelon Summer, my first young-adult novel,

in about a week. The title is courtesy of my father, who also

talked me out of my last-minute jitters and told me the third draft was

ready to fly. (After it gets back from the copy-editor, that

is.)

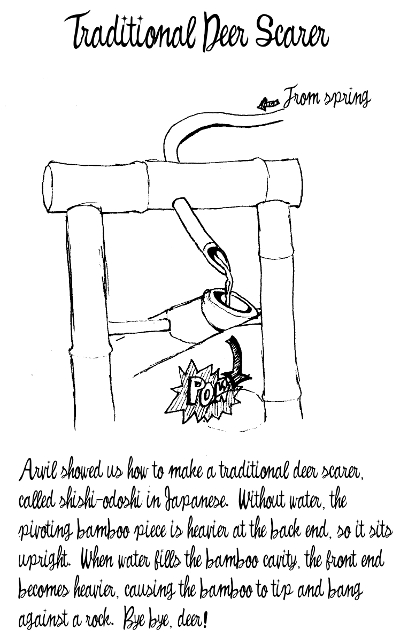

I don't have a cover yet (although I'm starting to envision one based on

a heart-shaped piece of watermelon), but I did add a few "Excerpts from

Thia's Notebook" to the back, of which the image here is one

page. As you can tell, the protagonist deals with some of the same

issues Mark and I have, although her solutions are often different from

ours. In fact, even though young adult isn't everyone's genre, I

think most of our blog readers will get a kick out of this little book

because it captures many truths about our homesteading experience that

are too personal to make it to the blog.

I'm going to use Watermelon Summer

as my first experiment with print-on-demand paperbacks too, although I

suspect it might take an extra week or two after the ebook becomes

available before you can buy a paperback. I may be dreaming, but I

like to imagine actual young people ending up with a copy of this book

and deciding that they want to homestead and perhaps explore the idea of

intentional community. Thus a print copy that's easy to pass

around and turn up in a used book store.

I hope you're engrossed in fun projects as well! Thanks for reading my ramblings.

The rain paused enough today

for me to go out and take this cattail comparison photo.

It's a lot less green then it

was 90 days ago....but it will be back in about the same time.

A month ago, when I erected quick hoops two through four,

one of our readers asked why I was devoting a quarter of that protected

space to Brussels sprouts. After all, the vegetable is supremely

cold-hardy, right? So wouldn't it be fine out in the open?

A month ago, when I erected quick hoops two through four,

one of our readers asked why I was devoting a quarter of that protected

space to Brussels sprouts. After all, the vegetable is supremely

cold-hardy, right? So wouldn't it be fine out in the open?

The photo at the top of

this post shows what happens to unprotected Brussels sprouts when

temperatures drop into the teens. The leaves tend to be fine, but

the sprouts themselves get nipped. Frost-nipped sprouts are

edible, but aren't quite as tasty, and if you don't eat them right away,

they start to rot.

In contrast, the photo to

the right shows one of the plants under the quick hoops. Lots of

tasty sprouts, undamaged by frost, and just waiting to be Christmas

dinner! We're eating the unprotected sprouts pretty hard right

now, even plucking the not-quite-solid heads, because temperatures are

forecast to droop back into the teens (or at least low twenties) this

week. Since Brussels sprouts are among Mark's top-ten favorite

foods, I haven't heard any complaints, but maybe that's because my

favorite Brussels-sprouts recipe starts with four slices of bacon....

In other Brassica-oleracea

news, it's also time to finish eating up all of the cabbages that have

been stored in the bottom of the fridge for the last month or so.

Our spring cabbages all go into soup base, but fall cabbages have more

life choices, sometimes being eaten plain as a raw finger vegetable,

sometimes being mixed with meat to make potstickers, sometimes getting

roasted (although they never taste as good as roast Brussels sprouts),

and sometimes going into experimental dishes like the

non-mayonaisse-based cole slaw I'm making above.

I clearly need to step it

up a notch, though, because we've got three heads left with outer

leaves turning brown that need to get eaten soon. What cabbage

recipes would you recommend for people who don't like traditional cole

slaw and don't enjoy sauerkraut?

"The decision to start an orchard

involves a decision to stay put. The first plant you want to get rooted

in the earth is yourself. That's what makes home orchards so valuable;

where they abound, they speak eloquently of a stable and responsible

community, the first necessity of a healthy civilization and a happy

culture."

"The decision to start an orchard

involves a decision to stay put. The first plant you want to get rooted

in the earth is yourself. That's what makes home orchards so valuable;

where they abound, they speak eloquently of a stable and responsible

community, the first necessity of a healthy civilization and a happy

culture."

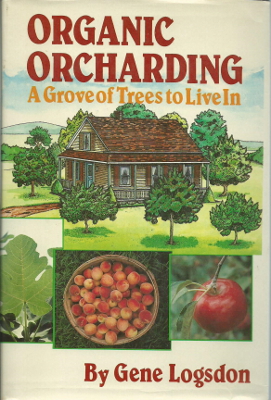

I've owned a copy of Gene Logsdon's Organic Orcharding

since I was in high school, but I don't think I ever read it until this

year. I do recall flipping through the book and dreaming about my

very own fruit trees, but am pretty sure I skipped the all-important

chapters on pest control and didn't read the other how-to chapters with a

very critical eye. So I figured it was time for a more thorough

re-read.

At the time, I also

didn't realize that Gene Logsdon was one of the great homesteading

authors who writes from personal experience, but with a dash of

experimental optimism. In fact, having read at least half a dozen

of his books so far, I'd say that Organic Orcharding is possibly his best --- too bad it's out of print!

Luckily for you, I plan to sum up the highlights in this week's lunchtime series. Stay tuned!

| This post is part of our Organic Orcharding lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We took part of the morning

off due to the rain soaked ground and cloudy skies.

It might take another day or

two for the creek to go down, but the chickens seem to be making up for

lost time after being cooped up most of the weekend.

"Why should only the outside world get time off for bad weather?" Mark asked Sunday. Before I knew it, I'd agreed to a one-hour delay on Monday morning.

And it was

a good day to sleep in. A full weekend of rain had filled my

wheelbarrow rain gauge and set the creek into moderate-flood mode.

(Moderate flood means we can't get out with hip waders, but I could

walk nearly all the way to the ford without being impacted by high

water.) Don't worry, rust-phobes, I flipped the wheelbarrow on its

side after taking this picture.

The flood reminds me that

winter is a season of tough choices for homesteaders. Do you

relax and soak up the peace and quiet in preparation for next year's

growing season? Or do you take advantage of days without pressing

plants and animals to get some big-picture projects done? Mark

leans toward the first option and I lean toward the second, so we meet

in the middle --- we slow down some, but also slip in projects

non-essential enough that they never make the cut during the growing

season. (And I get extra time to write.)

Winter is also a good

time to catch up on blog posts that didn't make it into the summer

queue. For example, I seem to have never mentioned how I

experimented with tempting our seven-year-old-but-not-yet-fruited dwarf

Yellow Transparent to make fruit buds. The problem tree was slated

for removal this spring since it sent up scads of watersprouts in 2012

after I pruned to remove extensive cicada damage.

But I decided to tie each long, vertical twig into a loop instead, and

the trickery does seem to have promoted the formation of fruiting

spurs! I'll keep you posted next year about whether actual flowers

are forthcoming.

What big-picture projects are you slipping in between snow storms?

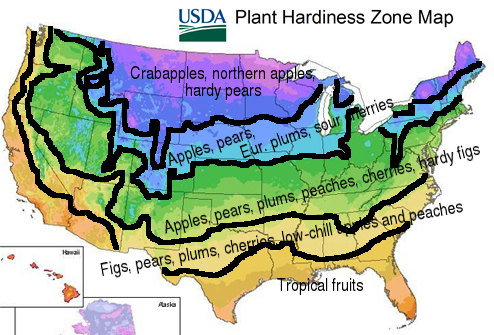

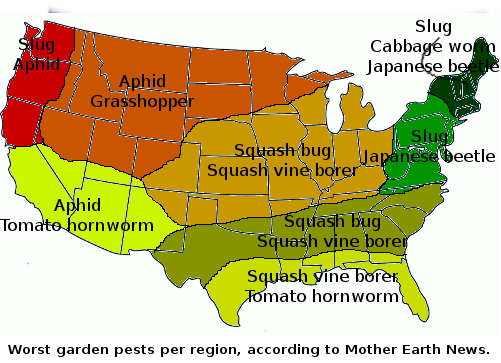

There's a reason I loved flipping through Organic Orcharding

before we got our farm --- it's a great book to dream by. Or, if

you want to pretend you're being scientific, you can use the excellent

charts for variety selection. For example, Logsdon recommends

starting your orchard planning by learning which species do well in

your climate. The map above hits the highlights, making it clear

that you really want to live in zone 6 or 7 if you plan to grow all

sorts of temperate fruits. Zone 8 is pretty good too, although

you'll need to choose low-chill apples and peaches, and colder zones

start restricting your choices pretty quickly.

Your next stop should be

Logsdon's excellent ripening-order charts, which I won't recreate here,

but which you can find on pages 28 and 50. While you're thinking

about seasonality,

you'll also want to consider adding some winter storers so you can

enjoy homegrown fruit after the snows fly. Logsdon doesn't list

storage times for pears (the other good storage fruit), but he does

include a handy chart of apple storage periods:

| Average storage months |

Maximum storage months |

|

| Grimes Golden |

2-3 |

4 |

| Jonathan |

2-3 |

4 |

| McIntosh |

2-4 |

5 |

| Cortland |

3-4 |

5 |

| Golden Delicious |

3-4 |

6 |

| Northern Spy |

4-5 |

6 |

| Red Delicious |

3-4 |

6 |

| Rhode Island Greening |

3-4 |

6 |

| Stayman Winesap |

4-5 |

6 |

| York |

4-5 |

6 |

| Rome Beauty |

4-5 |

7 |

| Winesap |

5-7 |

8 |

| Yellow Newton |

5-6 |

8 |

Finally, you

should take into account how much fruit your family can really

eat. Logsdon includes the yield figures below, which seem to be on

the low side according to some sources (which I've added

parenthetically). However, his figures might be the most realistic

for a chemical-free backyard orchardist.

| Species |

Estimated yield |

Apple:

|

|

| Pear |

3 bushels (up to 8 according to some sources) |

| Peach or nectarine |

3 bushels (up to 6 according to some sources) |

| Plum or apricot |

2 bushels (up to 6 according to some sources) |

| Cherry |

1 bushel (up to 3 according to some sources) |

I hope these charts help

you out if you're still in the planning stages. You may also get

some handy information out of my 99 cent ebook, Weekend Homesteader: December. Meanwhile, if you're ready to choose varieties and put trees in the ground, stay tuned for tips in later posts.

| This post is part of our Organic Orcharding lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Another wet and cold day inspired me to move some furniture around.

I realized Monday that

I'd never explored all the way up the holler behind our farm. When

we first moved here, I didn't want to trespass on someone else's

property, but a year or so ago, the owner of that property mentioned

that he didn't mind if I walked there since we let his son hunt down

onto the adjacent parts of our property. So I set off with the

camera to explore.

Long-time readers will

know that our farm seems to completely lack rocks --- not so up the

holler! Before long, I came across mossy boulder fields,

rock-loving ferns and liverworts, and even a pretty waterfall.

Granted, our main creek was at flood stage, so this waterfall on the

little spur creek might not exist in dry weather.

After

about half a mile climbing straight up, an old tire in the creek

suggested I was approaching civilization, so I looped back toward home,

this time walking on contour along the side of the hill. Along the

way, I discovered another perfect stump-dirt tree,

but I had nothing to collect the prime potting soil in (and doubt I'll

climb that high with a bucket). This tree is an ancient beech just

like my favorite stump-dirt tree, suggesting that something about that

species makes the best potting soil --- I've rooted around in the rotten

center of many other trees without finding such black gold. Maybe

rotting beech wood hosts a particularly good species of fungus or

beetle?

After

about half a mile climbing straight up, an old tire in the creek

suggested I was approaching civilization, so I looped back toward home,

this time walking on contour along the side of the hill. Along the

way, I discovered another perfect stump-dirt tree,

but I had nothing to collect the prime potting soil in (and doubt I'll

climb that high with a bucket). This tree is an ancient beech just

like my favorite stump-dirt tree, suggesting that something about that

species makes the best potting soil --- I've rooted around in the rotten

center of many other trees without finding such black gold. Maybe

rotting beech wood hosts a particularly good species of fungus or

beetle?

I'm afraid that after the halfway point, though, I stopped taking photos and started writing the sequel to Watermelon Summer

in my head. Oops. I really meant to write a non-fiction

ebook or two before scratching that itch, but it'll probably be good for

me to at least start another fiction piece while all of the lessons of

the first are fresh in my mind. And if people like the fiction, the sequel will be ready to go that much sooner.

I hope you're taking advantage of the winter lull to explore the wider world!

One of my favorite parts of Organic Orcharding

was comparing Logsdon's take on disease-resistant fruit varieties to

the selections chosen by more-modern authors like Lee Reich and Michael

Phillips. In case you're a new reader, you might want to start out

by browsing over these posts:

One of my favorite parts of Organic Orcharding

was comparing Logsdon's take on disease-resistant fruit varieties to

the selections chosen by more-modern authors like Lee Reich and Michael

Phillips. In case you're a new reader, you might want to start out

by browsing over these posts:

What's fascinating when comparing Logsdon's list to those of other

authors is how few varieties appear on both --- apparently trees go out

of style over time, so Reich and Phillips might not have even

experimented with the fruits Logsdon swore by in the 1970s (and vice

versa). For example, although Logsdon's list of pears matches up

with the ones mentioned in the post linked above, most of his resistant

stone fruits aren't on the above lists. Here's  Logdon's selection of stone fruits resistant to brown rot in case you want to give them a shot:

Logdon's selection of stone fruits resistant to brown rot in case you want to give them a shot:

- Alberta, Belle of Georgia, and Redhaven peaches

- Hagan Sweet and Morton nectarine

- Greengage, Ozark Premier, Redheart, and Stanley plums

However, Logsdon does

agree with the other authors that sweet cherries and nectarines are

trouble in humid climates (unless you're willing to grow the cherry

rootstock Mazzard for its small but disease-resistant fruits).

Which brings us to apples. Phillips' extensive (although organic) spray regimen

makes modern readers believe apples are impossible to grow in a

chemical-free fashion, but Logsdon instead considers apples the most

reliable of high-quality fruit species. He makes the argument that

if you choose resistant varieties (see below), use the worst apples for

livestock, the okay ones for cider or cooking, and only expect a third

of your fruits to be dessert quality, you can grow apple trees without

any sprays at all. That sounds like a regiment a homesteader can

get behind!

| Scab |

Fire blight |

Cedar-apple rust |

Powdery mildew |

|

| Adanac |

R |

|||

| Akane |

R |

|||

| Astrachan |

R |

|||

| Baldwin |

R |

|||

| Ben Davis |

R |

|||

| Black Twig |

R |

|||

| Chehalis |

VR |

|||

| Duchess |

S |

R |

||

| Earliblaze |

R |

|||

| Golden Delicious |

R |

S |

S |

R |

| Grimes Golden |

VR |

R |

||

| Jonafree |

VR |

|||

| Jonathan |

R |

S |

S |

|

| Liberty |

I |

VR |

VR |

R |

| MacFree |

I |

|||

| Macoun |

R |

|||

| McIntosh |

S |

R |

S |

|

| Northwest Greening |

R |

|||

| Nova Easy-Grow |

I |

|||

| Prima |

I |

VR |

||

| Priscilla |

I |

VR |

||

| Red Baron |

R |

|||

| Red Delicious |

S |

R |

||

| Sir Prize |

I |

S |

||

| Spartan |

R |

|||

| State Fair |

R |

|||

| Stayman Winesap |

R |

|||

| Transparent |

R |

|||

| Tydeman's Early Red |

R |

|||

| Wagener |

R |

|||

| Winesap |

S |

R |

||

| York Imperial |

VR |

I hope that gives an idea

of where to get started if you want to plant a completely spray-free

orchard. If I run across more lists of resistant varieties in

other books, I'll be sure to update with another post.

| This post is part of our Organic Orcharding lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our sky

pond is filled to the top with a healthy layer of ice on the top.

The trailer shades what

little sun would have hit this spot, which means it might take another

day or two before our recent duck visitor can fly south for the winter.

It

seems to be the trend this year for every blogger to post a holiday

gift guide, so I guess we'd better follow suit! I'll include some

specials on our own top products, plus a few gifts I heartily recommend

from the outside world.

It

seems to be the trend this year for every blogger to post a holiday

gift guide, so I guess we'd better follow suit! I'll include some

specials on our own top products, plus a few gifts I heartily recommend

from the outside world.

But first, don't forget home-made crafts! My mother's fire-starter tin

is still my favorite gift of the last year, and there are other good

ideas in the comments section of that post. Mark and I tend to

give gifts when the mood strikes rather than around any particular

holiday, and gifts that have been well-received this year include honey,

home-made jams, sweet potatoes, rooted fruit plants, and garlic.

Why not dig around the edges of your gooseberry bush and see if you've

got any baby plants to share with friends? Raspberries,

blackberries, comfrey, and perennial herbs are also likely to have

propagated themselves.

Okay, I know, some loved ones expect gifts with no dirt on them --- crazy people. We just put our homesteading calendar up on Amazon,

and we recommend this as a low-key way to trick non-homesteaders into

liking dirt. (Then you can give them one of the dirty gifts above

in 2014!) At the moment, our calendar is on sale for $5.99 + $3.99

S&H.

Okay, I know, some loved ones expect gifts with no dirt on them --- crazy people. We just put our homesteading calendar up on Amazon,

and we recommend this as a low-key way to trick non-homesteaders into

liking dirt. (Then you can give them one of the dirty gifts above

in 2014!) At the moment, our calendar is on sale for $5.99 + $3.99

S&H.

Or why not contact a

local farmer and buy some pastured meat for a loved one? The taste

alone will go a long way toward winning them over to the idea of

non-factory-farmed protein, and it will definitely boost their

health. If you live kinda close to us, my brother got some

pastured pork from these folks and it was delectable. You can also contact our pastured lamb supplier,

but I'm not sure if they have anything available at this time of

year. No matter where you find the pastured meat, it might be a

good idea to cook it up and invite your friends over for a holiday meal

and then send them home with the leftovers --- that way you can be sure

the meat will be cooked just right and will startle their taste buds.

What

about people who have been won over to homesteading, but who are just

getting started? A great option is a high-quality hand tool that

will last them the rest of their lives. The Trake is a cast-metal trowel that I use daily during the growing season, $22.65 on Amazon with free shipping on orders over $35. The Felco F-600 Hand Saw is so sharp it makes hand-cutting a breeze ($29.97 with free shipping available) and Mark's new RUKO knife looks like it's going to be our new favorite tool for butchering chickens and deer ($23.52 with free shipping available).

Vegetable seeds are

another good choice to give beginners. For people who have never

gardened before, I recommend leaf lettuce (mixtures are always fun),

Swiss chard (Fordhook giant is most winter hardy, but the ones with

colored stalks are striking), okra (Clemson spineless is our favorite),

summer squash (yellow crookneck avoids stem borers), and green beans (we

love Masai). This post will give you an idea of where to buy the seeds.

Of course, if your loved ones have chickens, you know what I think you should get them --- chicken waterers. We have a hidden sale going on right now just for our most loyal readers --- 10% off our top products.

Do order these ASAP, though, since we can't guarantee they'll reach you

by Christmas unless you order this week! (Barring floods,

waterers you order early next week should arrive in time too.)

Of course, if your loved ones have chickens, you know what I think you should get them --- chicken waterers. We have a hidden sale going on right now just for our most loyal readers --- 10% off our top products.

Do order these ASAP, though, since we can't guarantee they'll reach you

by Christmas unless you order this week! (Barring floods,

waterers you order early next week should arrive in time too.)

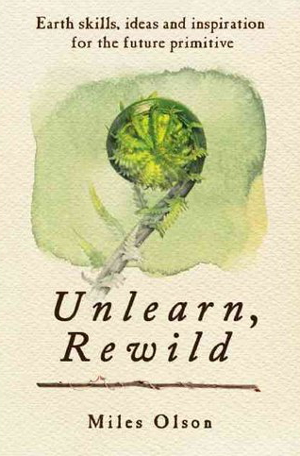

Which brings me to books. The up-to-date homesteader could benefit from this year's top reads: Paradise Lot and The Resilient Farm and Homestead. If they're dreaming about livestock, it's hard to go wrong with the Storey Guides. And, if they've got a kindle you can browse all of my ebooks here. (As a side note, my publisher let me know that my paperback

is out of stock on Amazon because they're currently changing

distributors and shipping all of their books from one warehouse to the

other, but hopefully it'll be back up there soon.)

I hope that's enough

brainstorming to get you thinking on a homesteading track this holiday

season. And if you didn't see your favorite gift here, leave a

comment below.

As I mentioned in my last post, Gene Logsdon's philosophy on dealing with pests and diseases is much less hard-core than Michael Phillips'

since the former is only growing food for his own table. In

general, Logsdon believes that as long as you can keep your fruit trees

alive, all other problems are cosmetic and can be treated or not as you

choose.

As I mentioned in my last post, Gene Logsdon's philosophy on dealing with pests and diseases is much less hard-core than Michael Phillips'

since the former is only growing food for his own table. In

general, Logsdon believes that as long as you can keep your fruit trees

alive, all other problems are cosmetic and can be treated or not as you

choose.

So how does

Logsdon deal with pests and diseases? He begins his

trouble-shooting by choosing resistant varieties (which I listed

previously), then moves on to low-key preventatives. For

fire-blight prevention, he recommends keeping nitrogen levels low,

perhaps feeding your trees only with a mulch of leaves,

cardboard, old hay, straw, manure, tobacco stems, grass clippings, or

clover. Meanwhile, he minds phosphorus levels as well since too

much of this nutrient will suppress mycorrhizal fungi, which are

particularly essential for healthy peaches. Finally, Logsdon

strives to keep problematic fungi in check by ventilating with summer

breezes.

One of our readers

sent me an email (with the photo above) a couple of weeks ago

mentioning how a woodpecker came by to deal with the borers that moved

into his apple burr knots, and that turns out to be Logsdon's solution

for codling moth larvae as well. One study showed that if you

allow natural woodland to grow up adjacent to your orchard, woodpeckers

can eat up to 52% of overwintering codling moth larvae. Meanwhile,

brush piles attract other beneficial birds, wild places attract

predatory insects, and even the lightning bug larvae living in unsprayed

lawns will eat slugs and snails. Maybe that's why Mark and I have

fewer non-fungal issues than I would expect --- because our core

homestead is surrounded by acres of natural forest?

This post is part of our Organic Orcharding lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Organic Orcharding lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It's been a tough week for

the White

Leghorn hen.

Today she came out of the

coop scratching around like her old self.

When I saw her up and about

the first thing I thought she could use is some warm scrambled eggs and

Anna agreed. With any luck she'll be able to re-join the flock in a few

more days.

I used to love Christmas

trees, but somewhere during the move to the farm, I lost the impulse to

put one up. Mostly, it's just a matter of not having space inside

for a big decoration, but Sarah's recent post reminded me that ornamentation doesn't have to take up much (or any) room.

"Do we have any

Christmas-tree lights in the barn?" I asked Mark. Upon hearing

that we didn't, I instead headed out into the woods with some clippers

in search of pine boughs. The pine branches were all too high to

reach, but young holly and hemlock trees were pushing up toward the

canopy as part of the forest's middle age. A bit of green

embroidery thread and a red ribbon I'd tucked away in that embroidery

bag turned the greenery into a garland around the base of our jam shelf.

I was surprised at how

much the bit of greenery brightened my day. I'll bet that's why we

started bringing in Christmas trees in the first place. What's your favorite space-saving, low-cost holiday ornamentation?

I'll end this week's lunchtime series with a couple of scattered tidbits from Organic Orcharding that caught my interest but which I couldn't seem to fit into a coherent post:

- Logsdon lists several "unusual" fruits (which are now relatively usual, like persimmons, mulberries, and figs). But he gives a very good warning: Before planting unusual fruits, take a few minutes to find out why they're unusual. For many of us, the old standbys might make more sense.

- When growing experimental seedlings, Logsdon recommends letting

each seedling grow for one year, then heading it back to eighteen

inches. This prompts the tree to fork. Let one fork grow

normally to test the seedling rootstock, but graft a known variety onto

the other fork. That way, if the seedling isn't worth eating, you

can just lop off that half of the tree and enjoy the good fruits from

the other half. (This is an especially handy tip if you're playing along with my apple-seedling experiment.)

I hope that's enough to

prompt you to hunt down a copy of the book and give it a read.

Maybe it's even in your local library?

(And, as one final side

note, the image at the top of this post is a wood engraving based on a

drawing by Winslow Homer, titled "Spring Farm Work -- Grafting" and

published in Harper's Weekly, April 30, 1870.)

| This post is part of our Organic Orcharding lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

When we built the East Wing, we made the entire south wall out of old windows reclaimed from an abandoned school.

Unlike

the double-glazed windows in the trailer, the single-glazed windows in

the East Wing make winters frigid. And in the summer, the interior

bakes.

Unlike

the double-glazed windows in the trailer, the single-glazed windows in

the East Wing make winters frigid. And in the summer, the interior

bakes.

The right thing to do is

probably to take out the windows and rebuild the wall, but I decided to

just add extra insulation and cover them up.

If we ever need glass, we'll know where to find it.

Thanks to your great recipe suggestions, we've used up two heads of cabbage this week! I cooked up the first head in this recipe emailed to me by a friend:

Thanks to your great recipe suggestions, we've used up two heads of cabbage this week! I cooked up the first head in this recipe emailed to me by a friend:

I liked Jennifer's recipe a lot, but even with the bacon, it just barely made the cut for Mark, so I moved on to the Cabbage Pizza Skillet

that another reader recommended. (Bonus that this one is a full

meal rather than just a side dish!) Cabbage Pizza Skillet will

definitely merit multiple repeats since Mark and I are always looking

for grain-free dishes that push those pizza buttons. I'd say this

one might be a little closer to lasagna than to pizza, but it tastes

great! Expect it to feed four hungry people.

With just one head of

cabbage left, we'll have to make some hard choices between the other

excellent suggestions. I'm leaning toward Erin's baked cabbage recipe, although we don't keep aluminum foil in the house. I wonder if it would work inside the Dutch oven....

I had a flat tire yesterday

coming back from Kingsport.

Something was stuck and I

couldn't pry the wheel free no matter how much I banged with the lug

wrench. Luckily I was sort of within walking distance. Even luckier was

the Deputy that dropped Anna's jury

duty notice off recently saw me walking and stopped to give me a

ride home.

Today Anna and I went back

and were able to push the wheel off with some help from the spud bar.

We've been eating a lot of venison lately, and this is one of my favorite recipes. For the stew:

- 1 pound of venison stew meat, cut into chunks

- a little bit of vegetable oil

- 2 large onions

- 1 quart of homemade chicken stock

- 1 quart of water

- 2 bay leaves

- a few sprigs of fresh thyme

- 3 large carrots

- 1 pint of frozen green beans

- salt and pepper to taste

Saute the chunks of stew

meat in oil until the outsides are brown. In the meantime, cut up

the onions and add them to the meat, cooking until tender. Then

add the chicken stock and water, bay leaves, and thyme (with the last in

a tea ball so it's easy to fish the stems out later) and simmer for at

least two hours, until the meat is very soft. Next, cut the

carrots into bite-size pieces and add them to the stew, simmering for

about half an hour longer until they're soft but not mushy. Add

the green beans then salt and pepper to taste.

As

a special treat, you can add dumplings, which I adore but don't make

often since we're mostly off grains. I do this by eye, but amounts

are roughly:

As

a special treat, you can add dumplings, which I adore but don't make

often since we're mostly off grains. I do this by eye, but amounts

are roughly:

- 1 egg

- about the same amount of yogurt as egg

- about half as much honey as yogurt

- a sprinkling of salt

- about half a teaspoon of baking powder

- enough flour to make a biscuit-dough consistency

Mix it all together, then plop four spoonfuls onto the top of your stew at the green-bean stage. Your soup must

be at a gentle simmer for this to work. Put on the lid and let

cook for about ten minutes, then flip the dumplings (which will have

expanded drastically) over, replace the cover, and cook for another ten

minutes. You can also add herbs to the dumplings, but they seem to

soak up enough of the broth to be quite flavorful as-is.

With the dumplings, this

serves four hungry people. Without the dumplings, it would serve

four less-hungry people, or three hungry people. Enjoy!

When is the creek too high

for an ATV crossing?

I'm not sure, but on Friday

the water height was getting close to the level of the dip stick, which

has a little rubber plug to prevent water from going in but I

speculated that it was better not to risk it.

How do you get an

introverted hermit to go to a party? Hold it less than a mile away

in the afternoon so she can get home in time to check on the chickens.

Kidding aside, this was

our neighbor's best solstice/Christmas celebration yet. It was

great to see everyone (although we did miss a few familiar faces).

(Plus, this post counts as documentary proof that I left the farm this month. See, Mom, I'm not really a shut-in!)

Thanks to all of your encouragement

(and to your bearing with my whining and complaining), my first work of

fiction is now up on Amazon! As you can tell from previous posts

on this topic, I'm not as confident in my abilities in this new genre,

so your kind reviews will definitely boost my mood considerably.

Thanks to all of your encouragement

(and to your bearing with my whining and complaining), my first work of

fiction is now up on Amazon! As you can tell from previous posts

on this topic, I'm not as confident in my abilities in this new genre,

so your kind reviews will definitely boost my mood considerably.

Watermelon Summer is a young-adult tale about an intentional

community that failed and a girl who refused to give up the dream. The

book is now available on Amazon for $2.99, and if you don't mind

waiting, you can use that link on Friday to pick up a free copy.

And for those of you who

are currently being scared off by the "young adult" part of the

description, take heart. 55% of young-adult books are read by

people over 18, and the

biggest demographic is actually among people 30 to 44 years of

age.

Chances are you'll fit right in. (Young adult is actually my very

favorite fiction genre due to its usual lack of muddiness and

willingness to tackle controversial issues.)

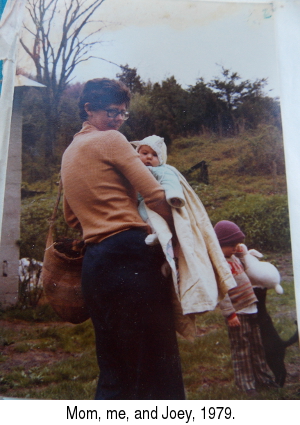

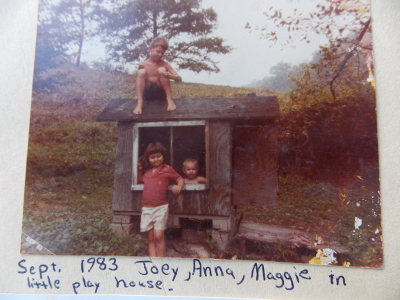

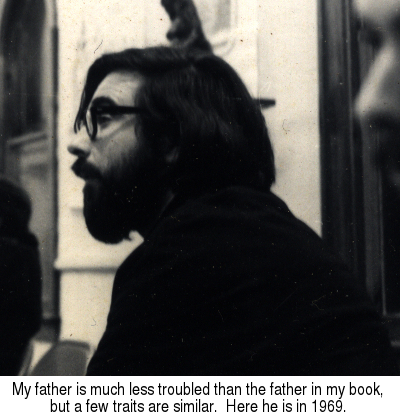

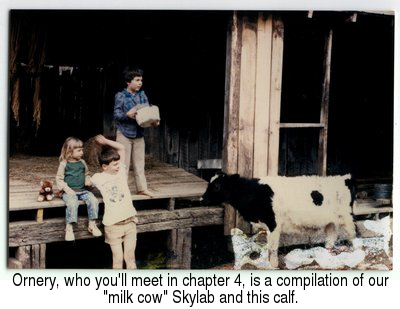

The rest of this week's lunchtime series consists of excerpts from the first couple of chapters of Watermelon Summer.

And to tempt you to stop back by even if you're not interested in

fiction, I'll be incorporating images from my past that made their way

into Watermelon Summer into the posts. Enjoy!

| This post is part of our Watermelon Summer lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I found out today where Lucy

has been spending her time these past few days.

Guarding her deer

trophy/dinner.

She's quite proud of herself,

and I think if she could talk she'd try to get me to help her bury most

of it so it can age like a fine wine.

To recap, we went into

winter with three hives. Our oldest hive is full of bees shipped

to us from Texas in spring 2012 who swarmed in spring 2013. Our second-oldest hive consists of a package we bought more locally this past spring, who were dusted with sugar to treat varroa mites this fall. And our youngest hive was a very long shot --- a swarm captured near the barn in late June.

If I had to guess in October when I started winterizing,

I would have said the barn swarm had a low chance of making it through

the winter, this year's package had a good chance, and the Texas bees

had a very good chance. Nature has already proven me wrong.

In early December, we

enjoyed one warm, sunny day, and I saw quite a few bees going in and out

of the barn-swarm hive. While I would have liked to believe these

bees were happy residents, I had a sinking suspicion that colony had

perished and a stronger hive was stealing their honey. I figured

if that was the case, there was nothing I could do about it, though, so I

left them alone.

But you know me --- I

like to know where I'm at. So this week I set out to see what I

could tell about our hives without opening them up. I started with

the oldest hive, who I'm most confident about, stuck my ear up against

the box...and heard nothing. Could they really be dead?

Clunk! The camera

around my neck knocked into the side of the hive box, and suddenly the

bees inside began buzzing angrily. Two happy lessons learned at

once --- if you don't hear bees in a winter hive, give the box a little

knock; and, this hive is alive!

The next stop was the

second-oldest hive, which I had a lot of faith in too. Here,

though, my faith didn't seem to be grounded in reality. Even after

knocking on the wood, no buzzing was forthcoming, so I opened up the

hive and found it dead. (Photos at the top of this post and to the

right.)

I'm a bit bamboozled

about what happened to this hive since it had a healthy population

(despite slightly higher than recommended varroa levels) going into the

winter. Now, there are only about 150 bees in the hive, a few

reaching into comb as if they'd run out of food, but most on the

bottom-board and entrance. If the hive wasn't also completely empty of honey, I'd say the culprit was colony collapse disorder.

But maybe the colony collapsed long enough ago that whatever usually

keeps other bees out of these hives dissipated, and the hive was robbed

out?

Without much hope, I

headed up to the barn-swarm hive, knocked on wood, and heard

buzzing! Despite very low numbers going into winter, this plucky

little colony has survived many nights in the teens. Maybe what I

saw two weeks ago was this hive's workers stealing all the honey from

the dead hive so the barn-swarm hive could make it through?

All of this musing aside,

I think I've decided not to go with straight-Warre-style management

next year, and instead to split the strongest hive. I've got two

boxes of Warre comb all drawn out, and that hive seems to have resilient

genetics, so it's probably a good idea to turn one into two.

That won't happen until

midspring, though. For now, I'll just hope the two remaining hives

last through the rest of the winter...knock on wood.

If I'd known I was going to fall in love that day

for the first time in my life, I would have taken the attendant

trials and tribulations in stride. But I didn't know, so I spent far

too many minutes considering whether my parents would buy me a

ticket back home to Seattle if I called up and begged. The

remainder of my stay in the West Virginia airport was devoted to figuring

out how to get to Kentucky, which meant trying to break through the

Appalachian language barrier.

You'd think that, since I mastered Spanish in

high school and picked up a smattering of French from Canadian

visitors, I would have had travel within the U.S. covered. You

also would have been wrong. Stopping by the information desk

at the airport felt like a Peanuts cartoon—you know, one

of those scenes where the teacher is talking and all you hear is "wa

wa wa, wa wa, wa wa." The ancient attendant's excessive

head-shaking seemed ominous, though, so I decided to try my luck

elsewhere.

You'd think that, since I mastered Spanish in

high school and picked up a smattering of French from Canadian

visitors, I would have had travel within the U.S. covered. You

also would have been wrong. Stopping by the information desk

at the airport felt like a Peanuts cartoon—you know, one

of those scenes where the teacher is talking and all you hear is "wa

wa wa, wa wa, wa wa." The ancient attendant's excessive

head-shaking seemed ominous, though, so I decided to try my luck

elsewhere.

I didn't remember my new smartphone (and the

airport's free wireless) until the nice lady at McDonald's laughed at

me for suggesting bus or train service to the Pikeville area.

She, at least, seemed to speak English, albeit with a mountain

twang—perhaps the problem at the information desk had merely been the

old guy's lack of teeth?—and she  was quite ready to give me

driving directions to Kentucky. Until, that is, I mentioned my

lack of wheels. Then the lady started to look concerned and to

call me "sugar," so I made up some excuse about having family who

could come and pick me up after all, then retreated to a waiting

area to figure out Plan B.

was quite ready to give me

driving directions to Kentucky. Until, that is, I mentioned my

lack of wheels. Then the lady started to look concerned and to

call me "sugar," so I made up some excuse about having family who

could come and pick me up after all, then retreated to a waiting

area to figure out Plan B.

Now, before you take my parents to task for

stranding me in no-bus-service West Virginia, let me speak in their

defense. Actually, I probably should back up about a week and

explain what a suburban girl like me was doing stranded in an

Appalachian airport....

I

hope you enjoyed this first installment of Forsythia's adventure.

Stay tuned for another chunk of her story tomorrow, or download the entire ebook of Watermelon Summer here.

| This post is part of our Watermelon Summer lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

What's an easy way to block

100% of incoming light and still have the option to turn the "light" on

when you want a little sunshine?

I cut a 2x4 and installed a

handle for easy removal and closing.

Why not use curtains? The

ones I tried let a good amount of light shine through.

Mom

sent me a fun birthday package full of odds and ends of crafting

supplies. The pieces that spoke to me immediately were two chunks

of fleece fabric cut into the shape of a hat. I figured, why not

sew them together and have headgear for hunting season?

Mom

sent me a fun birthday package full of odds and ends of crafting

supplies. The pieces that spoke to me immediately were two chunks

of fleece fabric cut into the shape of a hat. I figured, why not

sew them together and have headgear for hunting season?

Of course, I couldn't

help getting a bit fancy, which turned out to be my downfall.

After sewing the two pieces of fleece together, I cut a bit off another

piece of fabric Mom had given me (from somewhere far away --- want to

remind me where this came from, Mom?). The idea was to attach it

to the bottom and inside of the fleece so I could fold the bottom of the

hat up to have a different-colored brim.

What I didn't take into

account is that the other fabric lacked the fleece's stretch, and that

the fold took away some critical millimeters of head space. So my

final hat was too tight to beat out my old standby, shown on the left

and bought by my mother-in-law at a goodwill about five years ago for

fifty cents. I guess I'll have to give the don't-shoot-me hat to

someone a bit less big-headed than me.

It all started before I was born, when my

mother hopped in a VW bus with some friends and drove south from her

Massachusetts home to join a commune.

It all started before I was born, when my

mother hopped in a VW bus with some friends and drove south from her

Massachusetts home to join a commune.

"It wasn't a commune," Mom said, correcting my

wording just like every other time I'd ask her about Greensun.

"And I wasn't a hippie."

"Sure you weren't, Mom," I'd either say or think,

depending on how nice I was feeling at the moment.

"It was an intentional community," Mom reiterated

a week before I ended up stranded in West Virginia. The flier

that had restarted this conversation hit the trash can as Mom

continued her historical whitewashing. "You can call it a

community land trust if you want, but not a commune."

I wasn't buying it, but I knew what Mom was

trying to say with her adamant denial of hippiedom—she hadn't

smoked pot (supposedly) and I'd darn well better not either.

That message was coming through loud and clear, so I decided to

humor my mother on the semantics issue. "Sure,

Mom. You spent a solid year living in an intentional

community. Got it."

I'd been begging to visit the Greensun community

since I could pronounce words of four syllables, but Mom never saw

any reason to fly across the country to grant my wish. Never

mind that my biological father still lived there (I thought) and

that I've never met him.

(Oh, yeah—I'm a love child. Still not a

hippie, Mom?)

"You think you want to go there now, but you

really don't," Mom replied. (I decided to let it slide that my

mother seemed to think she knew my wishes better than I did, so I

stayed silent.) "When I left, there were plastic doll heads on

all the fence posts. Your father said they scared away

deer, but they mostly just scared away people. Very

creepy."

"You think you want to go there now, but you

really don't," Mom replied. (I decided to let it slide that my

mother seemed to think she knew my wishes better than I did, so I

stayed silent.) "When I left, there were plastic doll heads on

all the fence posts. Your father said they scared away

deer, but they mostly just scared away people. Very

creepy."

"So, I'll wear my doll-fighting gear," I

said. "No problem. I'll even bring a wooden stake if

it'll make you feel better."

Mom smiled despite herself. "Forsythia—" (Naming your child after a flower—another sign of

being a hippie. Just saying.) "—Do you really want to

spend your Europe money visiting an abandoned commune?"

At this point, I couldn't hold my tongue any

longer, so I crowed: "Ha! You admit it's a commune, which

means you're a hippie!"

Mom plowed right past that remark and continued

trying to talk me out of my plan. But even though I yes'ed

and no'ed appropriately, I was already at Greensun in my mind.

I

hope you enjoyed this second installment of Forsythia's adventure. Stay

tuned for another chunk of her story tomorrow, or download the entire

ebook of Watermelon Summer here.

| This post is part of our Watermelon Summer lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Poor Mark has had to bear

with four permutations of this cake, but I think I've finally got the

details ironed out. It's delightfully simple, richly chocolate,

and makes its own frosting all in the same pan.

First, preheat the oven

to 350 degrees and pull out a glass, 9x13-inch cake pan (or two 8x8-inch

square or two 9-inch round cake pans). Now prepare the frosting:

- 1 cup of dark chocolate chips

- 0.5 cups of heavy cream

- 1 cup of jam. (Blackberry or raspberry stands up to the chocolate best, but it wasn't bad with blueberry, and I might try strawberry next. Homemade, low-sugar jams keep this from turning sickly sweet.)

Melt the chocolate chips

in the microwave, being careful not to burn them. (If you start

with cold chocolate chips, it might take two minutes, but start with one

minute since that will usually melt room-temperature chips.)

Next, stir in the cream and jam. Spread the frosting mixture in

the bottom of your pan. (No grease is necessary in glass, but I'm

not sure about metal.)

Now, make the cake:

- 5.5 tablespoons butter

- 0.75 cups brown sugar

- 2 eggs

- 0.5 cups yogurt

- 0.5 teaspoons vanilla

- 1 cup all-purpose flour

- 0.5 teaspoons baking soda

- 0.5 teaspoons baking powder

- 0.25 teaspoons salt

- 0.5 cups plus 1 tablespoon cocoa (or just a heaping half cup)

- 0.5 cups boiling water

Melt the butter, then mix