archives for 11/2013

Sometimes it's a wonder

we get anything done around here. Take yesterday for

example. It was raining after lunch, so I wrote for an extra half

hour, then went out to pull up the peppers in preparation for some of

our last rye planting of the year.

But Huckleberry followed me out and danced around enough that he got stung on the tip of his tail by a honeybee. He ducked into my quick hoop

for safety, so I had to drag him out from the lettuce, then carried the

spoiled feline home along with a basket of cabbages. It sure is a

good thing Lucy is our usual work companion, not Huckleberry.

(If you haven't already,

you'll want to start with part

1, part

2, part

3, and part 4

from the very beginning of Growing

Into a Farm.)

(If you haven't already,

you'll want to start with part

1, part

2, part

3, and part 4

from the very beginning of Growing

Into a Farm.)

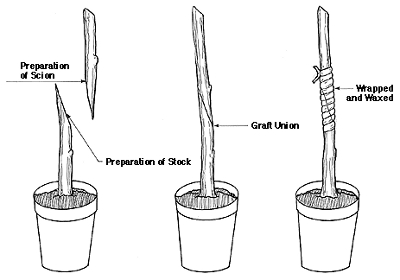

In early 2004, I

attended a grafting class and came home with a dozen baby apple

trees to begin my long-dreamed-of orchard. With the help of

my family, I ripped back honeysuckle and brambles and put the

trees in the ground...where they were soon eaten by deer and

overcome by weeds.

Meanwhile, the farm

slowly began to feel less like a retreat. During a weekend

over-night in April, I left my car parked along the secluded

country road and woke to found it had rolled down the hill into my

neighbor's field, just a few feet shy of being dunked in the

creek. Later, I learned that high-school kids enjoy spending

Friday nights partying down the road from my farm, and I can just

imagine their drunken enthusiasm at giving my little clown-car a

heave and watching it drift away. But at the time I felt

like the car episode was a malicious attempt by the local

community to push me out, and I began jumping at every sound when

camping at the farm. I had no phone and knew no one in the

area well—what would I do if my car ended up in the creek and I

was stranded there with no way out?

By the end of April, my

journals had gone strangely silent. I was still living an

hour-and-a-half's drive away from my property, and the chances of

moving in anytime soon seemed increasingly slim. My own

idealism, reinforced by that of my father and by my slim wallet,

made it unthinkable to consider buying materials or labor to build

my house, and I knew deep down that I couldn't finish it by

myself.

By the end of April, my

journals had gone strangely silent. I was still living an

hour-and-a-half's drive away from my property, and the chances of

moving in anytime soon seemed increasingly slim. My own

idealism, reinforced by that of my father and by my slim wallet,

made it unthinkable to consider buying materials or labor to build

my house, and I knew deep down that I couldn't finish it by

myself.

Over the next year,

I dropped by the farm from time to time to take pictures of the

wildlife, but my first relationship seemed to be at a

standstill. All that dreaming, planning, and saving, and one

winter had worn me down to a nubbin.

Want to know what

happens next? Growing

into a Farm is free on Amazon today! Even though

the ebook can

be read on any device, I'll also email you a free pdf copy today if

you'd rather --- just email

anna@kitenet.net with your request.

| This post is part of our Growing into a Farm lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Reading the reviews on Lucy's

Lectro

Heated Kennel Pad taught

me that the device has been known to malfunction, causing the

thermostat in the pad to keep it on all the time creating a situation

where it's too hot and will most likely burn out and stop working.

Lucy has been using hers a

lot lately, which makes me happy knowing she's comfortable, but I've

started testing it once a week by putting my hand on it to see if it's

too hot or burned out.

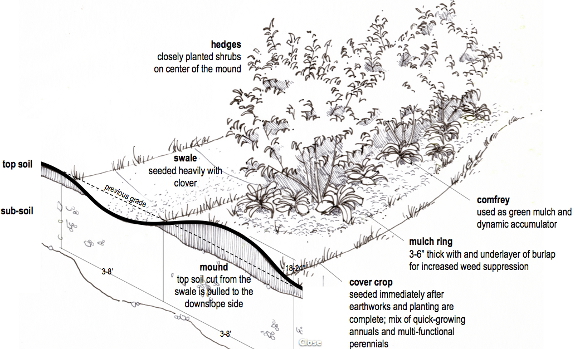

Do you want lots of fruit trees, but don't have much cash? As long as you're willing to experiment with grafting

(you'll pick it up fast), all you need is rootstock and

scionwood. Rootstock is pretty cheap (usually $2 to $4, plus

shipping), and you can also make your own by stooling (something I'm experimenting with this year --- more on that in a later post). Meanwhile, scionwood is often free if you find someone willing to swap with you.

Do you want lots of fruit trees, but don't have much cash? As long as you're willing to experiment with grafting

(you'll pick it up fast), all you need is rootstock and

scionwood. Rootstock is pretty cheap (usually $2 to $4, plus

shipping), and you can also make your own by stooling (something I'm experimenting with this year --- more on that in a later post). Meanwhile, scionwood is often free if you find someone willing to swap with you.

Last year, I pointed you toward (and used) the Northern Nut Growers' Association Scionwood Swap

(and also did some swapping here on the blog). But this year I

found an even better resource and wanted to make sure you all were aware

of it --- The North American Scion Exchange yahoo group. I think you have to join the group to see anything, then you go here

and look through each member's list, trying to find someone who has

what you want and wants what you have. I already tracked down a

source for my three wished-for apple varieties of the year --- Kidd's

Orange Red, King David, and Chestnut Crab.

There

are also various in-person scionwood swaps scattered across the

country, but I don't think there are any near us. And some

extension agents (like ours) offer grafting workshops every year where

you pay a small fee for your rootstock and are given a wide range of

scionwood to choose from.

There

are also various in-person scionwood swaps scattered across the

country, but I don't think there are any near us. And some

extension agents (like ours) offer grafting workshops every year where

you pay a small fee for your rootstock and are given a wide range of

scionwood to choose from.

The downside of all of

these ways of getting nearly-free fruit trees is that you have to wait

about two extra years for fruit. But, especially once your first

trees are bearing, it starts to feel like a good deal to get ten new

fruit trees for the price of one.

I think I may have damaged

the battery on our first ATV back in the early Summer when I

trickled charged it all night with this ancient charger.

A little research will show

that 4 amps is a lot for a small battery, and you need to disconnect it

after so many hours before it starts to overcharge.

The new AutoCraft charger

shuts off automatically and then shifts into a maintanance mode that

will slowly send a charge but only when it needs it. No more guess

work on when to shut off the old charger.

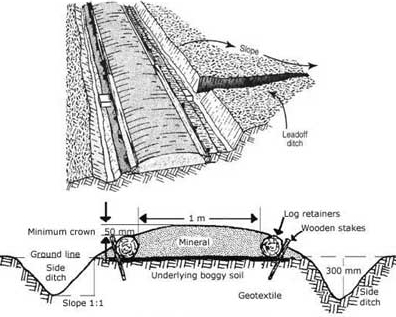

I really appreciated everyone's feedback on my ditch experiment, especially the reader who sent me to this excellent webpage.

Apparently, mounding the dirt from the ditches up on top of the road is

the solution, a technique known as a turnpike. For best results,

we'll want to splurge on some geotextile fabric to go under the new dirt

--- the stuff at Lowes is expensive ($1/linear foot and up), but

probably worth it. Maybe that will be our next big expenditure

(plus renting heavy equipment to make the digging go easier) once chicken waterer season kicks in next year and we're feeling more flush.

I really appreciated everyone's feedback on my ditch experiment, especially the reader who sent me to this excellent webpage.

Apparently, mounding the dirt from the ditches up on top of the road is

the solution, a technique known as a turnpike. For best results,

we'll want to splurge on some geotextile fabric to go under the new dirt

--- the stuff at Lowes is expensive ($1/linear foot and up), but

probably worth it. Maybe that will be our next big expenditure

(plus renting heavy equipment to make the digging go easier) once chicken waterer season kicks in next year and we're feeling more flush.

In the meantime, I

thought you might like to see the results of our hand-dug

experiment. Wednesday night's rain raised the groundwater level by

six or seven inches, so it was easy to see what was going on in our

little ditches. They definitely filled up, but they don't seem to

be moving the water away from the road so much as collecting it in

place.

I suspect that we need to commit to making the perpendicular ditch slope

all the way down to the alligator swamp (the old bed of Sinking Creek)

if we want the ditches to be effective in draining moisture away from

the road. If we feel really industrious this winter, we may dig

that side ditch out by hand, but it's brutal digging in the swamp --- so

much easier to forget about the problem and hope it goes away....

50 pounds of rye seed in the ground! (Actually, I gave Kayla about four pounds, so I guess I can only take credit for 46.)

50 pounds of rye seed in the ground! (Actually, I gave Kayla about four pounds, so I guess I can only take credit for 46.)

Where did I fit all that rye? Since my oats went in early this year, most started to bloom in late September, so I scattered rye seed amid the oats and had Mark weed-eat the latter down.

(You can see the result, several weeks later, in the photo at the top

of this post.) Meanwhile, I planted rye in the beds where crops

like tomatoes and squash died after our first frost, and in empty soil left after digging the fall carrots.

Of course, I still had rye seeds left after all that, so I started moving dirt around. I posted here about my gully terraforming experiment, and you'll need to visit my chicken blog

this week if you want to read about the swales Kayla and I dug in the

newest pasture to create tree alleys (and about the cute box turtle we

found in the process). All of that digging created bare soil, so I

topped it off with rye and finally hit the bottom of the bag!

Of course, I still had rye seeds left after all that, so I started moving dirt around. I posted here about my gully terraforming experiment, and you'll need to visit my chicken blog

this week if you want to read about the swales Kayla and I dug in the

newest pasture to create tree alleys (and about the cute box turtle we

found in the process). All of that digging created bare soil, so I

topped it off with rye and finally hit the bottom of the bag!

Of all our cover crops, I feel like rye handles wet soil the best and

produces the most biomass, so planting a full bag of rye feels a bit

like investing in an internet startup company --- a little bit of effort

for (hopefully) a lot of return. I'll report in the spring about

whether the rye I planted latest (November 1) covered the ground

adequately, and about whether I have any problem mow-killing it before our summer crops go in.

The kind of books I love the most are

inherently flawed, so let me start with the flaws up front in case

they're enough to scare you away (and then I'll tell you why The Resilient Farm and Homestead is tied with Paradise Lot as the best book of 2013

for permaculture homesteaders to read). Ben Falk's book

jumps around between personal experience (which I adore) and

rehashed theory from other books (which bores me, since I've read

the originals). The text doesn't entirely hold together and

is more like reading back through our blog archives

(if they were first sorted by subject), complete with

more-frequent-than-you'd-like typos.

The kind of books I love the most are

inherently flawed, so let me start with the flaws up front in case

they're enough to scare you away (and then I'll tell you why The Resilient Farm and Homestead is tied with Paradise Lot as the best book of 2013

for permaculture homesteaders to read). Ben Falk's book

jumps around between personal experience (which I adore) and

rehashed theory from other books (which bores me, since I've read

the originals). The text doesn't entirely hold together and

is more like reading back through our blog archives

(if they were first sorted by subject), complete with

more-frequent-than-you'd-like typos.

Those couple of

minor flaws aside, what drew me into The Resilient Farm and Homestead is that the book is 100%

genuine. The author has been experimenting with permaculture

techniques on his ten-acre Vermont farm for a decade, and he's up

front about what did and didn't work...even if it flies in

the face of mainstream permaculture wisdom. The book has

many beautifully-drawn diagrams, but it's also chock-full of

(equally beautiful) photos proving that Falk's methods really

work. Perhaps that's why my notes don't just hit pertinent

points from the text, they also include projects the book inspired

me to want to try on our own farm.

The Resilient Farm and Homestead is also handy for me,

especially, because Falk is farming on my level. Most

permaculture books today focus on the urban or suburban homestead

covering a fraction of an acre of land, but how do those

techniques fare in more extensive settings? At the other

extreme, there are Sepp Holzer and a

few other practitioners who make you want to turn hillsides into

terraces and to fence in dozens of acres of pasture...with what

heavy equipment? Falk's book walks right down the middle,

presenting techniques you can maintain at the few-acre scale with

(primarily) hand tools.

I'm going to

highlight Falk's most intriguing suggestions in this week's lunchtime

series, but this is one book you owe it to yourself to read from

cover to cover. If Goldilocks were reviewing this book,

she'd say, "This is not too big or too small --- it's just right!"

| This post is part of our The Resilient Farm and Homestead lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We decided to build a new

holding coop for an upcoming chicken retirement day.

Keeping it under 2 feet tall

makes it easy to reach in and grab a chicken.

First, a little bit of business. Congratulations to Stephen, winner of our free homesteading calendar! Be sure to email me

your mailing address and your calendar will go in the mail next

week. Jayne tells me the calendars will be showing up at her house

by the end of the week and she'll be mailing them out soon thereafter,

so this is a perfect time for everyone else to place your orders while the calendars are in stock. Now, back to the real post....

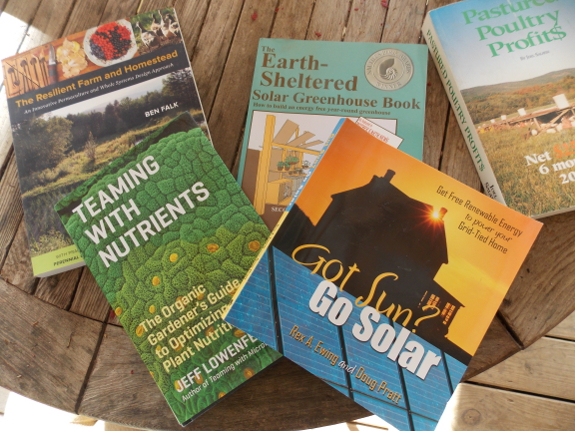

Every few years, I go

through my bookcase and pull out tomes I'm no longer using.

Fiction goes to the library and general-interest non-fiction goes to my

mother, but in-depth homesteading geekery needs another home.

Perhaps yours?

The following books are free to a good home. (I'll even pay postage.) It's first come, first served, so email anna@kitenet.net ASAP if you'd like a copy. I'll mark out each title as it's taken:

- Pastured Poultry Profits --- Joel Salatin

- Got Sun? Go Solar --- Rex A. Ewing and Doug Pratt

- The Earth-Sheltered Solar Greenhouse Book --- Mike Oehler

- Teaming With Microbes --- Jeff Lowenfels

- The Resilient Farm and Homestead --- Ben Falk

- Restoration Agriculture --- Mark Shepard. (Lunchtime series upcoming, so that link is just to Amazon.)

As a side note, my books

became much happier once I added wooden dividers to keep them all lined

up straight. My new method of spending half an hour on a

long-ignored household problem once a week is paying off!

Ben Falk's book

details his experiments at Whole Systems Research Farm, a ten-acre

tract of west-facing hillside on the border of zones 4 and 5 in

Vermont. The land was very run-down when Falk bought it, having been

logged, sugar mapled, pastured, and then clearcut for skiiing, with the

result that most of the soil had eroded away. Although soil maps

showed prime farmland over much of his land, the reality was actually

silty, gravelly clays covered by 0 to 4 inches of topsoil, with bedrock

within two feet of the surface in some places.

While others would have

been daunted by the poor soil, Falk took it as a challenge. He

embarked on ten years of experimentation, with the help of interns,

PDC groups and other visitors, and some hired summer help. The

result is six acres of silvopasture (perennial crops and grazing area

combined), along with rice paddies, vegetable

gardens, and some wild woodland.

One of the things I like most about Falk's writing is that he was inspired

by permaculture theory, but is a realist. He's found that, on the

ground, many of those theories don't hold water once you go beyond the

backyard scale, and he writes about how he tweaked various theoretical

systems to make them work on his farm. He also warns that,

although you can see inklings of how your experiments will turn out by

year five, you really need to wait at least one decade (or, better yet,

two) before declaring any system a success or failure.

My next few posts will delve deeper into Falk's systems, but I want to

end this installment with two words of wisdom I couldn't fit in anywhere else:

- If you have a big homestead, put a specimen of each crop in zone 1

as a barometer so you know when to harvest and when problems appear on the more far-flung crops.

- A great way to activate biochar is to toss it into your composting toilet.

Intrigued? Stay tuned to the blog for tomorrow's post to read more.

Don't have time to improve ten acres? Weekend Homesteader helps you focus on the most important (and easiest) projects to start where you're at.

| This post is part of our The Resilient Farm and Homestead lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It's been about a year since we started using our composting toilet, and the first bin is filled to the brim. Time to add another seat and change bins!

When we first built the composting toilet, I planned to store the sawdust in the central bin just like the author does in The Humanure Handbook.

Since then, though, I've decided it's better to simply fill up a big

trashcan with sawdust and use that to fill our five-gallon bucket, which

sits by the seat for ease of scooping.

When we first built the composting toilet, I planned to store the sawdust in the central bin just like the author does in The Humanure Handbook.

Since then, though, I've decided it's better to simply fill up a big

trashcan with sawdust and use that to fill our five-gallon bucket, which

sits by the seat for ease of scooping.

What's wrong with keeping

the sawdust in the middle bin? Filling a bucket out of the

central bin requires awkward bending over, the sawdust there has begun

to decay a lot due to contact with the wet ground, and it's also caught a

tiny bit of seepage from the used bin beside it, which makes the

sawdust much less fun to handle. Even if that last point is really

all in my head (I only saw a smidgen of toilet paper amid the sawdust

and doubt there was much seepage), it still seemed like a good idea to

shovel the sawdust out and use it as the bottom bedding in the new bin

since we want to fill our bin halfway with high-carbon material before

we start using it anyway. Plus, this way we can fill the middle

bin next year and give this past year's bin a full twenty-four months to

decay before it goes on the garden.

Deciding on sawdust

placement only took a couple of minutes, and I spent the rest of the day

building the new seat, but this post is already too long, so I'll save

that story for another day.

Ben

Falk is very adamant about peak oil and climate change, but he makes a

good argument for using heavy equipment for certain purposes while we

have fuel available. He wrote:

Ben

Falk is very adamant about peak oil and climate change, but he makes a

good argument for using heavy equipment for certain purposes while we

have fuel available. He wrote:

Mark tends to drag me

along kicking and screaming into a similar world of permaculture

realism, so I was interested to see what Falk considers worth spending

fossil fuels on. He focuses on five "leverage points" --- ways to

quickly improve your farm using the minimum amount of time and energy

--- and several of these strategies require heavy equipment on his

ten-acre scale:

- Clearing trees. Like us, Falk has found that it's tough to start with a forest as the base of your farm. He's very willing to pull out the chainsaw when it comes to clearing trees.

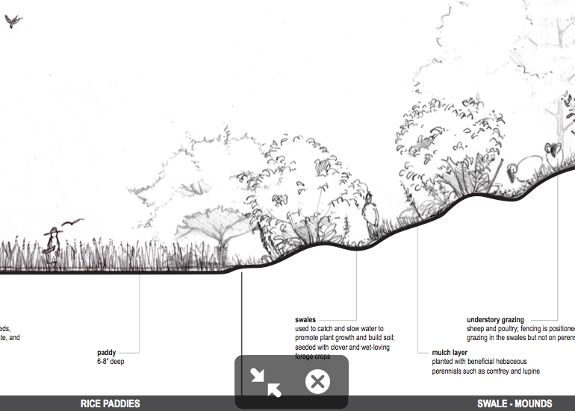

- Swales and fertigation. Rather than fighting waterlogged soil, Falk chose to create ponds and rice paddies that catch water during heavy storms, then ditches that can channel that water slightly uphill during droughts. Ducks in smaller ponds infuse the water with nitrogen, and that rich water is used to fertilize the rice paddies. Meanwhile, in drier parts of the farm, on-contour swales capture rain to hydrate trees planted upon the double-dose of topsoil along the downhill sides of the trenches. Elsewhere, island mounds (like what I use in the forest garden) raise plants out of waterlogged soil. All of these earthworks are easily created with Falk's favorite tool --- the excavator.

- Tilling and scraping to produce bare soil. Heavy equipment comes in handy here too, to create the disturbance required to give seeds and new plants a spot to grow. (On the smaller scale, I advocate kill mulches for this, but on a multi-acre scale, I'm not sure there's a fast alternative to tilling.)

- Broadcasting seeds and putting in perennials.

Now we're out of the stages that require lots of heavy machinery and

into the biological realm, which I always feel is pretty

self-explanatory. A couple of interesting points from Falk's book

include using a stropharia root dip for newly-planted trees, which allowed him to inoculate his

orchard

mulch for two-year yields of mushrooms, and intercropping buckwheat

between large vegetables (squash and tomatoes), then pulling out the

cover crop as the vegetables need space. I'll write more about

Falk's plant systems in a later post.

orchard

mulch for two-year yields of mushrooms, and intercropping buckwheat

between large vegetables (squash and tomatoes), then pulling out the

cover crop as the vegetables need space. I'll write more about

Falk's plant systems in a later post. - Grazing animals, especially ruminants and chickens.

As I'm sure you've heard elsewhere, animals round out ecosystems and

help close the fertility loop. Falk felt that goats and pigs

didn't fit his farm, that sheep were useful but should eventually be

phased out since they tend to need medications (perhaps to be replaced by cows), that broilers are handy, and that ducks are the perfect livestock for his farm.

If this post isn't already incendiary enough, I'll end with a Falk's stance on another energy source --- cold hard cash:

What do you think of

using the current wealth of gasoline and money to fuel the beginning

stages of permaculture systems? Is it a worthwhile expenditure if

the maintenance stages can be performed with little cash and with hand

tools?

| This post is part of our The Resilient Farm and Homestead lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We got the new chicken

holding coop done today.

The roof is sloped a bit to

let rain run off and the bottom is open to the ground.

When Bradley built our composting toilet

for us last year, we had to decide whether to have him put in one seat

or more. We opted for one, on the grounds that we'd likely change

our mind about the design later and want to make the second a little

differently. (Plus, it's hard enough to explain composting toilets

to visitors --- what if they accidentally used the wrong hole?)

Now that it's time for the bin swap, it's up to us to build the second seat.

The task was simple

enough that Mark let me try my hand at construction. So all the

photos will be from a distance, so you can't tell how edges don't quite

meet up right and a couple of screws didn't go all the way in....

We actually were quite

happy with Bradley's design, so I mostly did the same thing again.

However, I've noticed that the floor in front of the seat tends to get

wet when women pee, so I decided to make a liner out of metal

flashing. I figure this'll make sure everything goes straight down

the hole and doesn't end up soaking into the floor.

Hopefully there won't be

anything else to post about the composting toilet until this time next

year, but I'll keep you posted if we hit any snags.

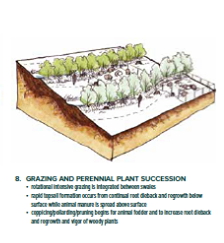

When

Ben Falk first moved to his farm, much of it was pasture, but he felt

it was "crazy to use fossil fuel to mow down the field every year, and I

let it go." At the time, he believed that allowing succession to

take place in the field (with grasses giving way to taller herbs and

finally woody plants) was the best way to heal his troubled soil.

However, when he finally got ready to add animals to his farm, Falk

discovered that neglect had been a severe mistake since "abandoned

poor-soil fields have a stubborn inertia." In other words,

reclaiming the grass was a tough process.

When

Ben Falk first moved to his farm, much of it was pasture, but he felt

it was "crazy to use fossil fuel to mow down the field every year, and I

let it go." At the time, he believed that allowing succession to

take place in the field (with grasses giving way to taller herbs and

finally woody plants) was the best way to heal his troubled soil.

However, when he finally got ready to add animals to his farm, Falk

discovered that neglect had been a severe mistake since "abandoned

poor-soil fields have a stubborn inertia." In other words,

reclaiming the grass was a tough process.

Falk's first impulse was

to scythe the old fields in hopes of returning them to quality pasture,

but he soon discovered that mowing and scything don't have the same

effect. While mowing patchy fields increases stem density of

grasses (filling in the gaps), scything actually tends to retard grass

growth unless you cut the ground very often. Infrequent scything

drops tall stems to the ground, where they form a mulch on the surface

and shade out new growth.

Next,

Falk figured grazing might do the trick. Unfortunately, grazing a

poor pasture with no mechanical cutting stage afterwards just selects

for the plants your livestock don't like, so his pastures weren't

getting any better. However, once Falk began grazing, then coming

behind the animals to mow and spread grass seeds, his pastures began to

provide more food for his sheep and poultry. Recently, he's also

been experimenting with burning as a way of jump-starting this process.

Next,

Falk figured grazing might do the trick. Unfortunately, grazing a

poor pasture with no mechanical cutting stage afterwards just selects

for the plants your livestock don't like, so his pastures weren't

getting any better. However, once Falk began grazing, then coming

behind the animals to mow and spread grass seeds, his pastures began to

provide more food for his sheep and poultry. Recently, he's also

been experimenting with burning as a way of jump-starting this process.

All of this isn't to say

that Falk is no longer a fan of scything. He's found that once

burning, grazing, seeding, and mowing have set back succession, he's

able to keep the pastures in check with grazing followed by

scything. Just like with his earth-moving,

Falk believes that it's worthwhile to use fossil fuels during the early

stages of reclaiming his land, but hopes to move away from machinery as

his farm improves.

| This post is part of our The Resilient Farm and Homestead lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Anna and I installed 8 cattle panels today in the new StarPlate pasture.

Planting

season begins around March on our farm, and for the rest of the spring,

summer, and early fall, the garden swallows up my time. I tend to

come up with ideas for about half a dozen ebooks while weeding each

summer, but don't have time to write during warm weather. The ones

that scratch the hardest at the insides of my eyeballs are the ones I

hit first in the fall, which this year was Growing into a Farm.

Planting

season begins around March on our farm, and for the rest of the spring,

summer, and early fall, the garden swallows up my time. I tend to

come up with ideas for about half a dozen ebooks while weeding each

summer, but don't have time to write during warm weather. The ones

that scratch the hardest at the insides of my eyeballs are the ones I

hit first in the fall, which this year was Growing into a Farm.

However, Growing into a Farm

has an unusual half-sister --- a young-adult novel about a

seventeen-year-old girl who returns the abandoned intentional community

where she was conceived. While I'm not so sure the book will be

any good (or will ever get finished since it currently seems to be

causing much weeping and gnashing of teeth), that's what I'm working on

at the moment.

I've gotten far enough into Saving Hippie Holler

that it asked for a cover, so I started experimenting. You can

see version 1.0 above --- Mark told me he liked it...but that it looks

like a science fiction book about aliens. Version 2.0 (below)

probably captures the theme better, but still seems to be lacking

something. Ideas?

In case you're curious, other book ideas waiting in the wings include:

In case you're curious, other book ideas waiting in the wings include:

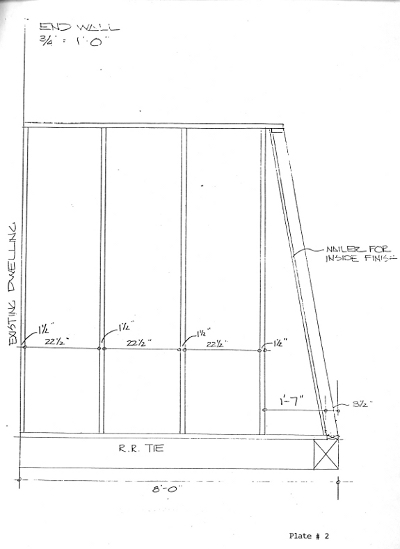

- Low-cost greenhouse add-on

--- I'm actually already about 80% through formatting and updating this

book which my father wrote when I was an infant, so it'll definitely

get finished the next time Saving Hippie Holler starts making me tear out my hear.

- Garden ecology --- I've been working on this one in my head for years, and I might finally be getting to the point where I have enough photos and data to make it a book.

- Several new chicken ebooks --- I just can't decide whether I'd rather write about chicken behavior, wild chicken feed, or designing a forest pasture.

- Permaculture deer --- We finally seem to have (mostly) won the war, so now might be a good time to share ways to work around (and with) the deer that want to destroy your homestead.

- I'm also vaguely considering trying to make print copies of my most popular ebooks available, but didn't hear too much enthusiasm when I broached the idea on facebook, so I might let this one lapse.

As a side note, I seem to have very low self esteem when it comes to writing fiction, so I could I could use some

comments stating, "What a great idea, Anna! I'd love to read a

fictional, young adult book!" Feel free to copy and paste those two sentences into the comment form below....

The

facet of Falk's farm that I was most interested in was his forest

pastures. He started his permaculture adventures with Edible Forest Gardens

and followed many of the authors' guidelines at first, but soon

discovered that on the multi-acre scale, he had to tweak the design a

bit. The first thing to go was complicated guilds, which were too

much trouble to keep up by hand, but Falk found that grazing animals

made a good replacement for herbs under the trees.

The

facet of Falk's farm that I was most interested in was his forest

pastures. He started his permaculture adventures with Edible Forest Gardens

and followed many of the authors' guidelines at first, but soon

discovered that on the multi-acre scale, he had to tweak the design a

bit. The first thing to go was complicated guilds, which were too

much trouble to keep up by hand, but Falk found that grazing animals

made a good replacement for herbs under the trees.

Next, Falk discovered

that rows are under-rated. Many in the permaculture community like

to scatter plants around willy-nilly, but on a large scale, rows save

time and money since you can fence animals out of a planting easily and

can get equipment between rows. Most of Falk's rows are on-contour

hedges of black locust and seaberry, both of which are planted close

together (half a foot to a foot apart for the locusts and four to eight

feet apart for the seaberries), then pollarded

to form hedges (and to produce firewood). Falk warns that it's

essential to commit to mulching trees heavily for the first three to

four years and to fencing out deer for the first two or three

years. After that, the more-established trees are resilient and

can handle a certain amount of neglect.

Although

I was intrigued by Falk's silvopasture system, I was disappointed to

see only diagrams, rather than photos, in his book --- that's always a

warning sign that an idea is still in its infancy. In addition,

Falk takes the permaculture party line about invasives, which I tend to disagree with, so he doesn't mention that seaberries are related to autumn olives and goumis and are potentially quite invasive, at least in Canada.

Although

I was intrigued by Falk's silvopasture system, I was disappointed to

see only diagrams, rather than photos, in his book --- that's always a

warning sign that an idea is still in its infancy. In addition,

Falk takes the permaculture party line about invasives, which I tend to disagree with, so he doesn't mention that seaberries are related to autumn olives and goumis and are potentially quite invasive, at least in Canada.

Those caveats aside, Falk's book definitely got me thinking about things I'd like to try, like tree alleys in our new pasture. If you want to read about his other systems --- like his rice paddies --- you'll have to check out The Resilient Farm and Homestead for yourself.

| This post is part of our The Resilient Farm and Homestead lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

A cold snap last night

motivated us to put up three more quick

hoops today.

Looks like we'll have even

more kale

than last year, which was a fair amount.

I put up a quick hoop over our last planting of lettuce in October,

and I meant to erect the other three quick hoops then too. But I

needed to make a decision about who to protect, and vacillation can take

awfully long time.

I put up a quick hoop over our last planting of lettuce in October,

and I meant to erect the other three quick hoops then too. But I

needed to make a decision about who to protect, and vacillation can take

awfully long time.

By the time I came back

to the project this week, a few things were clear. We started

eating Brussels sprouts from a few beds recently, but the long bed of

sprouts that got a lot of shade before the leaves fell from the trees

was trailing behind those in sunnier spots. If we want to enjoy

Brussels sprouts from that bed this year (which we adamantly do), we

need to extend the season, so that's one quick hoop accounted for.

The other two quick hoops are earmarked for leafy greens, but which ones? We've got three kinds of kale, tokyo bekana, tatsoi, mustard, and Swiss chard

in the ground, and there's not enough row cover fabric to protect them

all. While I could make another quick hoop, I don't think we'd eat

more greens than that anyway, so it's best to stick to two hoops of

leafy greens.

Huckleberry

reminded me that a few of these greens varieties are so tender they

won't last into December even under quick hoops. Despite the

brilliant coloration of the tokyo bekana pictured above, showing how

healthy the plants are, both this and the other Asian green are going to

bite the dust soon, as will our mustard. Those beds are best left

uncovered so I'll be sure to eat the tender greens up before real cold

weather hits.

Huckleberry

reminded me that a few of these greens varieties are so tender they

won't last into December even under quick hoops. Despite the

brilliant coloration of the tokyo bekana pictured above, showing how

healthy the plants are, both this and the other Asian green are going to

bite the dust soon, as will our mustard. Those beds are best left

uncovered so I'll be sure to eat the tender greens up before real cold

weather hits.

Since I'm opting to cover

the most winter-hardy greens in hopes of enjoying their leaves all

winter long, kale is the obvious winner. We devoted two whole

quick hoops to beds of kale, and still have other plants that will be

left uncovered for November munching.

One change I made to our leafy-greens coverage compared to other years

is that I went ahead and covered our Swiss chard as well as our

kale. This decision mostly came about because the chard is at the

end of the Brussels sprouts row and didn't require its own hoop, but I

also noticed last winter that Fordhook Giant appears to be just about as

winter hardy as our favorite kales (Red Russian and Dwarf

Siberian). (Our third kale variety this year is Laciniato --- I'll

report on its hardiness next spring.)

If you're still interesting in reading more about our quick hoops, I devoted a whole chapter to the topic in The Weekend Homesteader. (You can also read the same information in the 99 cent ebook Weekend Homesteader: October.)

Despite having to do more mending this year, we're going into our third

season using the same fabric, so the cost comes to about 10 cents per

square foot per year, and drops every year the structure stays in

use. I can't say enough good things about quick hoops and eating

fresh food all winter --- try it and you'll be sold too!

We attached our cattle

panels with some nylon

rope.

Future adjustments will be

easier this way.

It's a Long Road to a Tomato,

by Keith Stewart, wasn't quite what I expected. For some reason, I

figured the book was one of those

city-guy-goes-to-the-country-and-gets-a-chicken books (which I often

enjoy), and in some ways that is the gist of the story. Stewart

and his wife did move out of New York City to start an farm...but the

book sums up twenty years of experience, and the author did far more

than keep a chicken.

It's a Long Road to a Tomato,

by Keith Stewart, wasn't quite what I expected. For some reason, I

figured the book was one of those

city-guy-goes-to-the-country-and-gets-a-chicken books (which I often

enjoy), and in some ways that is the gist of the story. Stewart

and his wife did move out of New York City to start an farm...but the

book sums up twenty years of experience, and the author did far more

than keep a chicken.

Stewart developed a

12-acre organic-vegetable farm, run by himself with the seasonal help of

six interns per year (who require more management than Hispanic

laborers would have, but who he pays less). Not counting large

investments (like tractors, of which Stewart owns three), his annual

expenses come to just shy of $150,000, which should give you an idea of

the scale of his operation. He grows all of the usual high-end

vegetables and herbs, with garlic being one of his favorites, and he

trucks the produce into the big city to sell in a Manhattan farmer's

market every week.

While I heartily recommend It's a Long Road to a Tomato

for anyone considering beginning their own market garden, the book has a

wider appeal. If you're new to the topic, you'll probably learn a

lot about problems with our current agricultural system, running the

gamut from encroaching development to government regulations. And

even if you're not interested in agricultural policy or starting your

own organic farm, you'll probably enjoy the chapters in which Stewart

writes about life on the farm, while you'll definitely love his wife's

woodcuts.

In the end, I didn't learn anything new from It's a Long Road to a Tomato, but I enjoyed the read. Chances are you'll feel the same.

Friday was one of our

winterization days.

This is the second year in a

row we remembered to run our small engines dry.

The getting ready for winter

ritual is almost complete.

The best way to get good apples is to grow them yourself. We're getting there, but it takes time.

The second best way would

be to team up with a farmer whose tastes and growing philosophy mesh

with your own and pick your apples from his orchard. Or buy his apples at a farmer's market. I wish I'd gotten more than half a bushel of those delectable Winesaps, but I'm afraid they're all gone now.

Third best is to find a

fruit stand that sells semi-local apples by the bushel. While

these are never quite as delectable as homegrown, they're much tastier

(and cheaper) than store-bought. The Bureau of Labor Statistics

says Red Delicious apples averaged $1.41/pound in September. In

contrast, the going rate for a bushel of Winesaps in our area seems to

be about $24, or 50 cents a pound. (And they taste vastly better

than Red Delicious.)

We couldn't eat a bushel of apples before they go soft if we kept them in the house, but the fridge root cellar

has room between baskets of carrots to keep apples crisp. They

say not to store apples with potatoes, but my carrots don't seem to mind

the ethylene-producing neighbors.

What do you stock up on from the fruit stand to keep your winter meals cheap and tasty?

Several of you recommended that I check out Restoration Agriculture: Real-World Permaculture for Farmers

by Mark Shepard, and I can see why since the book documents the rare

example of an extensive food-forest system in its prime.

Unfortunately, the gems are deeply buried --- I barely found anything

worth noting down until I was halfway through the book. There are

also lots of typos, and several glaring mis-statements that put the rest

of his facts in question, along with pages of rants and regurgitation

of other books. So, I can't entirely recommend Restoration Agriculture, but if you're willing to skim and think critically, it can be a handy addition to your permaculture education.

Several of you recommended that I check out Restoration Agriculture: Real-World Permaculture for Farmers

by Mark Shepard, and I can see why since the book documents the rare

example of an extensive food-forest system in its prime.

Unfortunately, the gems are deeply buried --- I barely found anything

worth noting down until I was halfway through the book. There are

also lots of typos, and several glaring mis-statements that put the rest

of his facts in question, along with pages of rants and regurgitation

of other books. So, I can't entirely recommend Restoration Agriculture, but if you're willing to skim and think critically, it can be a handy addition to your permaculture education.

I'll post more about the

nitty-gritty of Mark Shepard's system later in the week, but for now,

let me give you a quick run-down on his farm and vision. Shepard's

parents were hobby farmers, so he soon became familiar with the basics

of growing his own vegetables. However, as an adult, he rejected

the conventional backyard system, realizing that most of us aren't

growing anywhere near all of our own food since we continue buying

staples from the grocery store (which equates to buying from factory

farms). Could he develop a system in which farmers can grow

perennial staples (preventing erosion, providing wildlife habitat,

etc.), so crops like chestnuts and hazelnuts replace corn and beans in

the average American's diet?

Shepard put his dream to

the test on a 106-acre farm in southwest Wisconsin, on the border

between zone 3 and 4. He developed methods of mixing tree, vine,

and bush crops with livestock in such a way that some of the work could

be done by conventional equipment that most medium-to-large-scale

farmers already have. Stay tuned for more on the design of New

Forest Farm in later posts.

| This post is part of our Restoration Agriculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The new chicken

holding coop is a huge

improvement for processing day.

We had no problems with the

first 5 birds, but the last one had plans of escaping before I caught

him by the leg.

When Mom came over to visit last weekend, she oohed and awed over the beauty of my cover crops,

as usual. But this time around, she had more purpose to her words

--- she wanted to know if the radishes were the same as the daikon

radishes she's been buying at the grocery store.

When Mom came over to visit last weekend, she oohed and awed over the beauty of my cover crops,

as usual. But this time around, she had more purpose to her words

--- she wanted to know if the radishes were the same as the daikon

radishes she's been buying at the grocery store.

I've

posted before that the oilseed radishes grown as cover crops are in the

same species as daikon radishes, but probably aren't varieties bred for

flavor, so I felt

like it couldn't hurt anything to give Mom a few roots to sample.

She took them home, sliced them up, and gave me one thumb up. "I

like them OK," Mom emailed. "They don't seem quite as spicy as the

Daikons, which sell, bigger, at Food City for $3.19, but they are about as spicy as most regular radishes."

On the other hand, my sister enjoyed the flavor of the cover crops, so I'm pulling up a few more to toss in the fridge root cellar.

I could leave them in the ground, but with lows forecast to reach 10

degrees this week, I don't want to risk them freezing and rotting.

As a side note to locals, the winter forecast for our region is finally out from my favorite weather guru:

"So

based upon the OPI Index (October Pattern Index) they are basically

saying a cold, wintry start mid-November to early December will give way

to mildness that dominates the heart of winter through January 2014

before more average, colder conditions develop in February toward end of

the season."

"So

based upon the OPI Index (October Pattern Index) they are basically

saying a cold, wintry start mid-November to early December will give way

to mildness that dominates the heart of winter through January 2014

before more average, colder conditions develop in February toward end of

the season."

In other words, don't

lose heart during this frigid week, but do take your cabbages in and

frost protect any last figs out there.

I left you hanging in yesterday's post,

so I figure several of you are probably wondering --- what exactly does

Mark Shepard's farm look like? He based his design on the natural

oak savanna ecosystem, but replaced wild plants with productive,

domesticated species and laid everything out in rows with 23-foot alleys

in between the trees. His primary species include:

I left you hanging in yesterday's post,

so I figure several of you are probably wondering --- what exactly does

Mark Shepard's farm look like? He based his design on the natural

oak savanna ecosystem, but replaced wild plants with productive,

domesticated species and laid everything out in rows with 23-foot alleys

in between the trees. His primary species include:

- American X Chinese chestnuts

--- Those of us further south can just plant Chinese chestnuts, but

Shepard lives too far north for the pure Asian stock to thrive and is

experimenting with hybrids. He plants his chestnuts 12 feet apart.

- Apples --- Since Shepard is trying to make a profit from his farm products, the trickiness of growing blemish-free apples organically

is something he had to figure out. His solution is to use most of

his apples for juice, to plant resistant varieties, to prune high, to

graze in early spring to get rid of diseased leaves, and to let pigs eat

the blemished fruits off the ground. His apples are planted 24 feet apart.

- American X European hazelnuts --- There's been quite a bit more breeding since I wrote this lunchtime series on the topic, but the ideas are the same. In Shepard's system, hazels are planted four feet apart in rows with apples.

- Berries --- Shepard also plants raspberries, blackberries, currants, gooseberries, and grapes in the understory. He trains his grapes onto tree limbs, then prunes the tree leaves above the grapes so the latter get plenty of light.

- Edible and medicinal mushrooms --- These are grown on logs under the trees.

In the alleys between

these trees and shrubs, livestock clip back the grasses and add another

food (and income) source. Shepard recommends using Salatin-style grazing,

with the number of each type of animal based on the number of

cattle. For example, if your farm has just one cow, Shepard

recommends two hogs (Tamworth, Red Wattle, or Berkshires), four turkeys,

one sheep, and variable chickens (with the amount of chickens dependent

on how much you want to feed them). Geese or goats can replace

sheep, although Shepard seemed very anti-goat.

I wish Shepard had given

us many more details on his farm, but this is all I could pull out of

his book! Hopefully it will be enough to give many of you new

ideas, though, just as it set me off on my tree alley experiments.

| This post is part of our Restoration Agriculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

What's the best way to be an arm-chair homesteader? With one of our calendars, of course.

Our copies just showed up in

the mailbox, and those of you who preordered will probably see yours

soon too. The real thing looks twice as nice as the proof copy

did.

Mom says she doesn't mind

gift-wrapping and inserting a gift note at no extra charge. Just

leave a message in your order when you check out via paypal.

Then you and your loved ones can enjoy all of the beauty of homesteading with none of the work. Now that's the way to be an arm-chair homesteader.

I thought I had

fire-starting all figured out until this year, when we got our firewood

from a different ecosystem. Usually, our homegrown firewood comes

from the floodplain, meaning that we have plenty of box-elder for

kindling and walnut for hotter fires; when we buy wood, it tends to be

oak from national forest mountain nearby.

But the drier Starplate pasture

was full of scrubby trees that grow up in old fields. None

(except one tulip-tree) were very large in diameter, but some resisted

the splitting ax like crazy. I'm guessing that maybe this ultra-hard wood is hop-hornbeam?

I'm so used to starting

fires with box-elder kindling that I thought pale wood equated to easy

starts. It turns out that was a false correlation, as I discovered

when I tried to start a fire with another pale wood (not sure what it

was since the bark had fallen off). Since then, I've realized that

the easy way to tell which variety to use for kindling (especially if

you don't know the species and can't look up its Btu potential) is to

heft the round in your hand. Heavy wood takes more effort to catch

a flame, while light-weight wood will flare up in an instant.

(That's assuming your firewood is dry, of course.)

Some things never change,

though. Lucy continues to be a firewood thief, so I figure these

new species taste about the same as the old did to a dog palate.

And the cats still love curling up in front of the stove. Don't

worry, Emily, Strider was in the comfy chair too until seconds before I

snapped that shot.

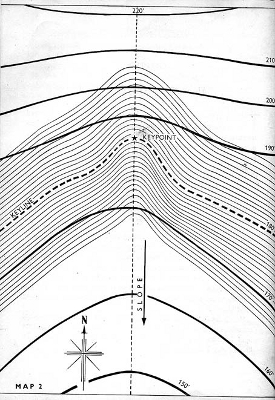

Although I complained earlier that Restoration Agriculture

included too much rehashing of other books, my very favorite part was

actually his explanation of water management using keylines. I've never

tracked down a copy of P.A. Yeomans' book on the subject and thus

didn't really understand the system, so I appreciated Mark Shepard's summary.

I've heard people bandy

around the term "keyline" for years, and it took me a while to realize

they weren't talking about ley lines. (Yes, my brain does

automatically turn off when I hear, or think I hear, certain

words.) I'd also read several authors writing about bringing water

from the valleys to the ridges, and I couldn't quite figure out what

they were talking about since we all know that water flows

downhill. Mark Shepard's chapter on the topic cleared up all of my

misunderstandings.

First of all, a keyline

is simply the spot on the landscape where a steep slope turns shallow,

as you can see in the photo above. The idea is that by managing

water along this line, you can move the least dirt while having a large

effect downhill.

Why do you want to have

any effect at all? I chose to photograph the hill I did because

that's the one that feeds the extremely high groundwater in our forest

garden. According to Yeomans (the originator of the keyline

concept), swampy bottomland results from mismanaging the water

upstream. To correct the problem, you dig a swale (an on-contour

ditch) along the keyline so that water doesn't whoosh right down into

the swampy bottom, but instead flows gently (along a 1% downhill slope)

to drier areas to the side. This is known as a spreader swale, and

it's what folks mean when they talk about moving water from the valleys

to the ridges --- you're not technically bringing water uphill, but you

are moving it from a wetter area to a drier area. The result is a

more productive, damper area to the side of the keyline, and a more

productive, drier area in the flat zone directly downhill.

Another facet of the keyline system is pocket ponds, which are just like my sky pond,

but are located at keypoints (the center of the keyline). These

vernal pools aren't meant to stay wet all year, but they do act as surge

protectors, giving you somewhere to store excess water during wet

seasons and then disbursing that water to the surrounding area once

things dry out.

The final part of the

keyline system consists of subsoiling (running a small plow deep in the

earth) parallel to the swales each year to break up hardpan.

Similarly, you can build more swales parallel to the keyline swale and

plant trees along them, resulting in easy-to-handle rows that still work with (rather than against) your site.

Understanding keylines got me thinking that I should definitely give the

concept a try above the forest garden. I've had pretty good luck

moving trees upward into raised mounds, but wouldn't it be wonderful not

to have a swamp there each winter? Sounds like another fall

earth-moving project just waiting to be explored!

| This post is part of our Restoration Agriculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I've been using these Stihl

work gloves for about 6 months now.

I liked them at first, but it

turns out the band at the wrist tends to slip forward creating a

situation where the fit isn't as tight, causing rubbing during

aggressive activities.

The next pair of work gloves

I buy will be the Palomino

grain cow hide gloves I

started out using back in 2008.

This is an excellent question, and one I didn't really really pay

attention to when I first pulled out my shovel. I made the raised

beds parallel to the slope with no drainage option, mostly because you

want raised beds to be flat on top, and it's much easier to make them

flat if you build parallel to the slope.

Since reading Eric's comment, I've been keeping my eye on the beds and I've been pleasantly surprised to see very little water

building up in the aisles between. Granted, it's been

relatively dry here (you know, an average of only about half an inch of

rain per week), so the groundwater isn't terribly high. But my sky

pond is still about halfway full, despite the fact that Lucy thought

there was some kind of critter in the drainpipe from the roof and ripped it to shreds

a couple of months ago, meaning only groundwater is recharging the

pond. (I really should fix that....)

Since reading Eric's comment, I've been keeping my eye on the beds and I've been pleasantly surprised to see very little water

building up in the aisles between. Granted, it's been

relatively dry here (you know, an average of only about half an inch of

rain per week), so the groundwater isn't terribly high. But my sky

pond is still about halfway full, despite the fact that Lucy thought

there was some kind of critter in the drainpipe from the roof and ripped it to shreds

a couple of months ago, meaning only groundwater is recharging the

pond. (I really should fix that....)

Barring extreme waterlogging in my new gully beds, I figure I'll just

plant with the water in mind. For example, I discovered this

summer that the watermelons planted in a raised bed above some very

soggy soil did much better than those in the main part of the garden, so

those would be a good choice for our chinampa beds. And for all I

know, next year will be as dry as this one was wet, and I'll be glad

for every ounce of water retained.

Or maybe I'll change my mind and add some drainage! Only time will tell.

By the way, I decided not to bore you with a full-blown advertising post, but did want to alert you to the new sale on our chicken waterer website

--- I hope it makes your holiday shopping easier! Cold weather

has been keeping me inside, so I'm also making changes to my email lists

--- please stay alert and click to confirm that you want to stay on my

lists if you see an email from me in your inbox. Thanks for

bearing with the marketing interruptions!

The last tidbit I mined out of Restoration Agriculture

was really a venue for further exploration. Shepard explained

that the USDA has five officially-sanctioned types of agroforestry,

which means we can hunt down scientific studies on each of these topics

to give us jumping-off points for our own explorations. The first

two --- wind breaks and riparian buffers --- are self-explanatory and

are more about protecting the rest of the farm and ecosystem than they

are about growing food, but the others have food potential.

The last tidbit I mined out of Restoration Agriculture

was really a venue for further exploration. Shepard explained

that the USDA has five officially-sanctioned types of agroforestry,

which means we can hunt down scientific studies on each of these topics

to give us jumping-off points for our own explorations. The first

two --- wind breaks and riparian buffers --- are self-explanatory and

are more about protecting the rest of the farm and ecosystem than they

are about growing food, but the others have food potential.

Despite the name, forest

farming (as defined by the USDA) isn't the same as forest gardening (as

defined by the permaculture community). This is a closed-forest

type of setting with shade-tolerant plants including medicinal herbs

(ginseng, etc.), ramps, gooseberries, currants, and edible mushrooms

grown underneath the trees. I feel like this form of agroforestry

is most useful for folks who need a cash crop, less so for trying to

feed ourselves.

Silvopastures are a concept I've written about here before (and which have informed my own pasture experiments).

The idea is to combine trees and pasture, with the aim of producing 40

to 60% canopy coverage. An easy way to start a silvopasture is to

plant trees along permanent fencelines, focusing primarily on

deep-rooted species so they don't compete too much with the grass.

Fruit trees, pecans, walnuts, hickories, chestnuts, and pines have all

been used in official studies.

The

final type of USDA-approved agroforestry is alley cropping, with rows

of trees separated by annual field crops. The trees are often

oaks, walnuts, or pecans, and the trick (again) is to keep the trees'

roots from competing with the annual crops. Since most people are

plowing their annual crop fields, they generally use a subsoiler each

year as well to cut back tree roots that are trying to invade the main

fields, tempting the trees' roots instead to dig deep.

The

final type of USDA-approved agroforestry is alley cropping, with rows

of trees separated by annual field crops. The trees are often

oaks, walnuts, or pecans, and the trick (again) is to keep the trees'

roots from competing with the annual crops. Since most people are

plowing their annual crop fields, they generally use a subsoiler each

year as well to cut back tree roots that are trying to invade the main

fields, tempting the trees' roots instead to dig deep.

If you're trying to

create your own perennial-based system like I am, I highly recommend

checking out extension-service documents about these various

agroforestry systems online. It's always a good idea to know

what's been tried before you go out to reinvent the wheel.

| This post is part of our Restoration Agriculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We woke up this morning with

a frozen driveway.

The truck was frozen too, but

once we jump started her she was ready for some trips to the barn.

A few loads of straw and

most of our garbage got hauled before the ground thawed.

I don't think I ever

understood the expression "Seize the day" until I moved to the

farm. But now I know that, sometimes, it's worth throwing the list

out the window and going with the flow.

Thursday

morning, we woke to a 14-degree farm, and when I took Lucy for her walk

through the floodplain, nothing even crunched under my feet --- the mud

was solid. The weather was so wet this year that we haven't had a

single day in which we could drive the truck back to our core

homestead, but frozen works too.

Thursday

morning, we woke to a 14-degree farm, and when I took Lucy for her walk

through the floodplain, nothing even crunched under my feet --- the mud

was solid. The weather was so wet this year that we haven't had a

single day in which we could drive the truck back to our core

homestead, but frozen works too.

Three hours later, the

truck started slipping around as it brought in the last load of straw,

and Mark had to pull it out of the ruts with the ATV. But we'd filled the barn with 33 bales of straw and had cleared out a year's stock-piled garbage (two truckloads full). If Mark had tried to do all of that hauling with the ATV, it would have taken him at least a week.

By the way, Mark's newest heated chicken waterer incarnation was still flowing at 14 degrees. Want to guess how low it'll go?

I hooked up a medium

sized hot water tank

today.

It's on a switch because we

plan to only use it once or twice a day.

See the comfrey bed above? I dug out every single root I could find from that spot last year,

broke the plants up into smaller segments and stuck them into the

ground elsewhere with no water or care. Not only did all the new

starts thrive, the bed now appears to be just as full as comfrey as it

was before I dug the plants out. Time to do it all again!

While I'm on the subject,

I thought comfrey transplanting day would be a good time to regale you

with the comfrey dos and don'ts I've learned over the years:

Comfrey dos:

- Do use comfrey medicinally as a poultice.

I once cut my foot wide open running barefoot amid glass. The

wound really should have had stitches, but Mom gave me a comfrey

poultice, and it healed right up in no time.

Do plant comfrey in pastures.

Although the mature leaves are not their favorite food, chickens will

eat comfrey if you accidentally let the pasture get overgrazed. The birds also enjoy young comfrey leaves even when they have other options. Best of all, comfrey plants are so hardy even chickens can't kill them.

Do plant comfrey in pastures.

Although the mature leaves are not their favorite food, chickens will

eat comfrey if you accidentally let the pasture get overgrazed. The birds also enjoy young comfrey leaves even when they have other options. Best of all, comfrey plants are so hardy even chickens can't kill them.- Do plant comfrey beyond the eventual spread of your fruit trees. I've started lining paths in the forest garden with comfrey. I can cut the leaves and use them as nutrient-rich mulch, and as long as the comfrey isn't close to my trees, they don't compete much for nitrogen.

- Do start a comfrey nursery bed. Within a couple of years, one plant can turn into dozens of plants that are ultra-easy to move elsewhere.

Comfrey don'ts:

Don't take comfrey internally. According to some sources, comfrey can be a carcinogen, so I figure it's better not to risk it.

Don't take comfrey internally. According to some sources, comfrey can be a carcinogen, so I figure it's better not to risk it.- Don't put a comfrey poultice on an infected wound. Comfrey makes your skin grow back over a cut so quickly that it can seal infections in, so wash that wound well first!

- Don't plant comfrey within the root zone of young fruit trees. If you have awesome soil, you might get away with this, but comfrey stole nitrogen from my fruit trees and caused their leaves to yellow. Comfrey didn't seem to cause problems in the deeper shade beneath a mature peach, though.

- Don't expect to ever plant anything else where your comfrey is now. Comfrey doesn't run like mint (although it will slowly spread to each side over the years), but it is just as tough to eradicate. So, think hard about what you want to have in that spot in twenty years before putting in your comfrey.

- Don't mulch with comfrey stems. Leaves make a great mulch, but the stems can root and

start a new comfrey patch where you don't want one. Similarly, you

won't want to let even a tiny root end up in your compost pile or the

soil will be full of comfrey plants.

Anything else you'd add to my comfrey instruction sheet?

This bungee 4X5 cargo net expands our garbage hauling capacity by about 50%.

"I'm curious about your book experience. After doing many ebooks and one big book what

is would be your preference for future books? Are you finding that

sales are still doing well for all your books or are there standout

ones?"

"I'm curious about your book experience. After doing many ebooks and one big book what

is would be your preference for future books? Are you finding that

sales are still doing well for all your books or are there standout

ones?"

I know this question

isn't really homesteading-related, but several of our readers have

self-published ebooks and/or have been holding out to sign on with a

publisher, so I thought the topic would be helpful for more than just

Mikey to hear about. I also highly recommend ebooks to

homesteaders as a potential income source, so even if you haven't

written one yet, you might want to take note.

Of course, this post is also partly because I just wanted a chance to crunch data. After all, I let a publisher take The Weekend Homesteader and run with it as an experiment to test this precise question. And no experiment is worth much without a conclusion.

First, a caveat: I don't actually know how exactly many paper books I've

sold and how much I've made from the operation. I won't get my

first statement and royalty check until next month (yes, that is 19

months after turning in my manuscript). I'm also a bit fuzzy on

how much I'll make per book --- I think it's about 65 cents, but that

depends on how each book was sold. (For comparison's sake, I make

35 cents every time one of my 99 cent self-published ebooks is sold and

75 cents every time one of my $1.99 ebooks is sold.)

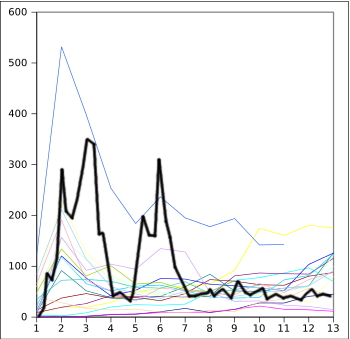

What I do have is Bookscan data about The Weekend Homesteader

from Amazon's Author Central website. (They warn that the data is

usually underreported by about 25%, so I'm correcting it slightly in

the calculations below.) In the chart above, you can see that I

sold a lot of books for a couple of months, sold only a few when my

first printing ran out and we had to wait on the second set of books to

arrive, and then, after another couple of months of high sales, settled

in to selling about 50 books a week.

Selling

a lot of books during the launch then a slow-but-steady stream later

seems to be the case with my ebooks as well. The chart to the left

shows estimated income from my paperback (in bold) versus all of my

ebooks over their first 13 months in the public eye. As you can

see, my best-selling ebook --- Trailersteading

--- actually made significantly more than my paperback did during that

period (and I didn't have to wait a year and half for the money).

My other ebooks didn't make quite as much as my paperback, but on the

other hand you have to keep in mind that the paperback is equivalent to

12 ebooks, so I figure I made a lot more per word even with my

moderately-selling ebooks. (As a side note: data for ebooks that

have come out in 2013 hasn't been added to this chart --- $10 Root Cellar looks like it might give Trailersteading a run for its money.)

Selling

a lot of books during the launch then a slow-but-steady stream later

seems to be the case with my ebooks as well. The chart to the left

shows estimated income from my paperback (in bold) versus all of my

ebooks over their first 13 months in the public eye. As you can

see, my best-selling ebook --- Trailersteading

--- actually made significantly more than my paperback did during that

period (and I didn't have to wait a year and half for the money).

My other ebooks didn't make quite as much as my paperback, but on the

other hand you have to keep in mind that the paperback is equivalent to

12 ebooks, so I figure I made a lot more per word even with my

moderately-selling ebooks. (As a side note: data for ebooks that

have come out in 2013 hasn't been added to this chart --- $10 Root Cellar looks like it might give Trailersteading a run for its money.)

But

did the paperback boost my "brand" enough that it was worth taking the

per-word hit? The chart to the right looks at ebook sales two

years before, one year before, and then during the time my paperback has

been out. Although it looks like the paperback might have

increased ebook sales during the launch period (which is also when Trailersteading came out), if anything, it decreased sales later in the year. That's because once my publisher's version of The Weekend Homesteader became available in ebook form, my individual-month ebooks were no longer eligible for Amazon's KDP Select program,

which is a real money-maker. Plus, I'll only get about 65 cents

if someone buys the publisher's ebook or paperback, while I'd make $4.20

if that person instead bought all 12 months straight from me.

But

did the paperback boost my "brand" enough that it was worth taking the

per-word hit? The chart to the right looks at ebook sales two

years before, one year before, and then during the time my paperback has

been out. Although it looks like the paperback might have

increased ebook sales during the launch period (which is also when Trailersteading came out), if anything, it decreased sales later in the year. That's because once my publisher's version of The Weekend Homesteader became available in ebook form, my individual-month ebooks were no longer eligible for Amazon's KDP Select program,

which is a real money-maker. Plus, I'll only get about 65 cents

if someone buys the publisher's ebook or paperback, while I'd make $4.20

if that person instead bought all 12 months straight from me.

So, to answer Mikey's

question, I don't plan to publish any more print books with a publisher

anytime soon --- in this digital age, it doesn't feel like I really need

a middle man. (And wouldn't you rather spend $1.99 for an ebook

than $13.50 for a paperback?) Perhaps if I was the kind of person

who liked to go on tour, having a paper book would boost the brand

enough to make the it worthwhile, but since I'm a confirmed hermit,

ebooks seem to work better for me.

Which is not to say I regret publishing The Weekend Homesteader

on paper --- if nothing else, it probably reached a lot of eyes my

words wouldn't otherwise have appeared to. And I always like

experiments! But for those of you who are on the fence about

uploading your words straight to Amazon, I say go for it --- you

probably won't regret it.

I'm stealing Mark's

posting spot to apologize for any website problems you've had this

weekend. Joey and I have been playing around with the site to make

it go a little faster, but unfortunately it broke a few times in the

process. The good news is that using the search and comment

features now seems to be about twice as fast! Thanks for putting

up with site maintenance --- I think it's all over now (unless I break

anything else).

Edited to add:

I'm making one more change at 6:30 pm, so you may have trouble again

for a few hours Sunday evening. Tomorrow, hopefully, this will all

be sorted out!

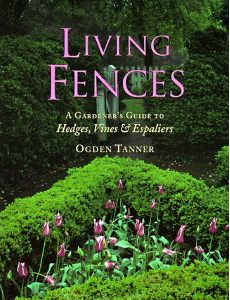

Long-time

readers will know that I'm interested in hedges, even though I haven't

really experimented much with them. I like the idea of planting a

living barrier that will keep deer out and chickens in even after our

metal fences rot into the ground. It would be a major bonus if

that barrier also produced food for the chickens and for us. So I

was thrilled when I stumbled across Living Fences: A Gardener's Guide to Hedge's, Vines, & Espaliers, by Ogden Tanner, in our local library.

Long-time

readers will know that I'm interested in hedges, even though I haven't

really experimented much with them. I like the idea of planting a

living barrier that will keep deer out and chickens in even after our

metal fences rot into the ground. It would be a major bonus if

that barrier also produced food for the chickens and for us. So I

was thrilled when I stumbled across Living Fences: A Gardener's Guide to Hedge's, Vines, & Espaliers, by Ogden Tanner, in our local library.

Unfortunately, the book

isn't really what I was looking for (which I suspect might not exist),

since it's mainly a list of species you might want to use in ornamental

living fences, along with some data on their construction from a

landscaper's point of view. However, I did find some information

that will be helpful when I finally get our borders weed-free enough

that I can start my hedge experiments. Here are species that might

make the cut:

| Species |

Features |

Spacing in a hedge |

Questions |

| Flowering quince (Chaenomeles speciosa) |

Thorny barrier; edible fruits; informal hedges 4-6' tall |

2.5-4' |

Can fruiting quinces be used the same way? |

| Cornelian cherry (Cornus mas) |

Edible fruit; informal or form hedges 4-15' tall |

1-4' |

|

| Cockspur hawthorn (Crataegus crus-galli) |

Thorny barrier; informal hedge up to 30' tall |

3-4' |

Would fruits be edible to chickens? |

| European beech (Fagus sylvatica) |

Classic European hedge plant; formal or informal hedge 6-20+' tall |

2-10' |

Would American beech work as well? Can chickens eat their nuts? |