archives for 10/2013

I'm very ashamed to

say that I missed celebrating our farm's birthday this year ---

sorry, farm! This is much worse than forgetting

my marriage anniversary because Mark and I have an understanding that we don't do

anniversaries and don't give each other gifts on holidays.

The farm and I, on the other hand, have an agreement that she will

feed me and make me happy and I will notice her at least once a

year.

Our seventh year on

the farm was rough in certain ways, but delightful in

others. The rough patches weren't really blog material,

consisting primarily of Mark hurting his back last fall and not

being able to sleep right for a couple of months, plus the

heartbreak we felt when our

community-building project went south this spring. On

the other hand, those problems were counteracted by the

awesomeness of Kayla

and by a huge influx of homegrown fruit (my favorite food group).

Looking back at the post I made on the

farm's last birthday, it's astonishing to see how much progress we've made in

twelve short months. (Well, nearly thirteen now.) The

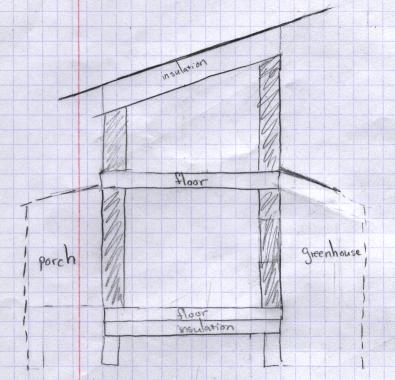

composting

toilet and front

porch have vastly increased our standard of living, and Mark

has enjoyed his ATV

(even though I'm concerned by the amount of damage it's done in

the driveway during a very wet year --- we'll have to attack that

issue soon). My first

paperback hit bookstores and Mark invented a completely

new chicken waterer. And, of course, we kept adding

new perennials to the garden, building soil, and increasing our

pasture area.

Looking back at the post I made on the

farm's last birthday, it's astonishing to see how much progress we've made in

twelve short months. (Well, nearly thirteen now.) The

composting

toilet and front

porch have vastly increased our standard of living, and Mark

has enjoyed his ATV

(even though I'm concerned by the amount of damage it's done in

the driveway during a very wet year --- we'll have to attack that

issue soon). My first

paperback hit bookstores and Mark invented a completely

new chicken waterer. And, of course, we kept adding

new perennials to the garden, building soil, and increasing our

pasture area.

And despite the angst I mentioned previously, our tranquility

levels have remained pretty high, perhaps due the ponds

I played with building this summer, but mostly due to Mark's even

keel. I am eternally thankful that my original dream of

sharing my life with a piece of land didn't materialize as

planned, instead turning into a threesome --- me, Mark, and the

farm.

Those of you who don't

follow our

facebook page probably don't know that Walden Effect is

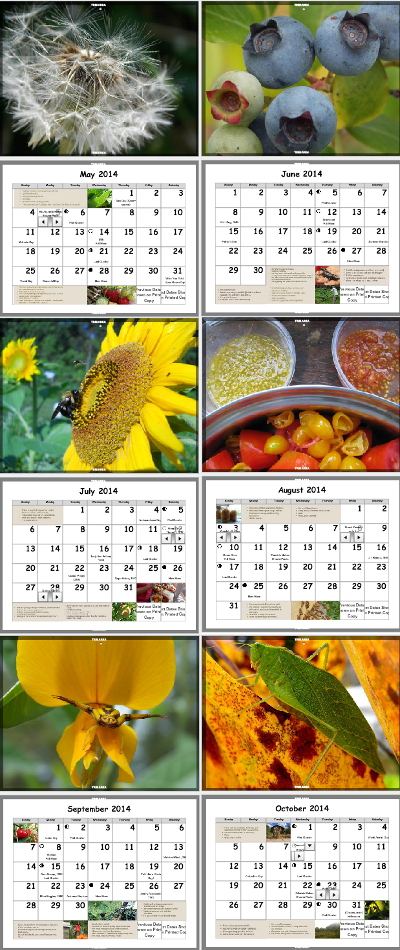

coming out with a wall calendar this year. Mark's

step-mother makes family-history calendars for her clan and asked

if we'd like her to make one for our readers. We said sure!

Those of you who don't

follow our

facebook page probably don't know that Walden Effect is

coming out with a wall calendar this year. Mark's

step-mother makes family-history calendars for her clan and asked

if we'd like her to make one for our readers. We said sure!

The calendar is still

being designed, so I can't tell you anything definitive yet, but

we're envisioning it showcasing the best of our blog photos and

also including a bit of text to keep you on the right homesteading

track each month. I'm writing very short summaries of each Weekend

Homesteader

project, and am also including a list of annual chores and events

based roughly on this

post (but

generalized to only include tasks that are probably relevant to

you). We plan to include phases of the moon, meteor showers

and eclipses, solstices, equinoxes, cross-quarter days, national

holidays, and maybe some birthdays of permaculture-related folks

(and a hobbit or two).

If we can find a cheap

source of vegetable stickers, we'll also take one facebooker's

suggestion and include a set of stickers so you can easily mark

planting dates. I'm considering including an insert with

first and last frost dates for major cities across the country and

charts showing how to use those dates to figure out your own

planting times.

If we can find a cheap

source of vegetable stickers, we'll also take one facebooker's

suggestion and include a set of stickers so you can easily mark

planting dates. I'm considering including an insert with

first and last frost dates for major cities across the country and

charts showing how to use those dates to figure out your own

planting times.

Anything else you'd

like to see on a wall calendar? I don't plant by the moon,

so don't really feel I have enough experience to add biodynamic

planting suggestions, but just about anything else will at least

be considered.

Calendars will go on

sale here around the first of November, and we're hoping to keep

your cost down to $9.99 per calendar (maybe with $2 shipping per

order?). Right now, I'm thinking of playing it safe and

printing only 200 calendars, so it would help to get a head count

in the comments section, especially if you are thinking of

ordering more than one. The calendar will be glossy and

pretty, a good gift for the gardener on your list!

(And a big thank-you

to Jayne for being the driver behind this calendar project!)

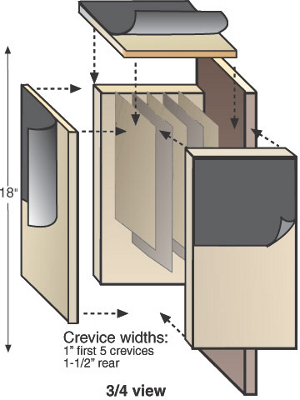

It's been a year since I

first made the deluxe

chicken carrier.

My conclusion is that

chickens cackle less when they are in the dark.

The wire cage we used before

worked, but I remember more cackling, which I'm guessing equals more

stress, which is always something to avoid with poultry.

The weather is getting

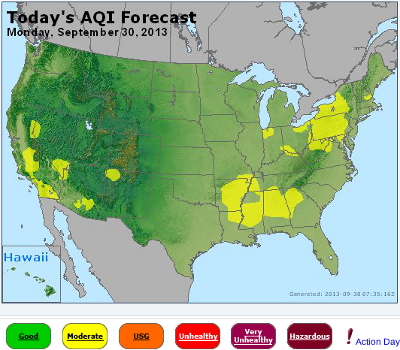

chilly...and controversies over wood stoves are popping up all

over. One came into my inbox and another into my blog feed

last week, so I thought I'd weigh in.

The weather is getting

chilly...and controversies over wood stoves are popping up all

over. One came into my inbox and another into my blog feed

last week, so I thought I'd weigh in.

First, from our

regular reader Roland:

woodstove. Mostly as a backup and because of the cozy factor. But after reading the [The Fireplace Delusion and Woodsmoke Health Effects: A Review], I changed my mind."

For those of you,

like me, who hate following links, here's the upshot, excerpted

from the first link:

Meanwhile, various

blogs in the homesteading world are posting rants against the

EPA's new policy that would make it illegal to sell your old wood

stove if it emits more than 7.5 grams per hour (g/hr) of

particulates. Here's a sampling of the headlines to give you

a feel for the tone of the pieces:

"Off Grid Attack: EPA To Outlaw Many Wood Burning Stoves"

To help explain my take

on the matter, let's go back in time. Mark and I started out

with a monstrous

wood stove that spewed forth smoke (see the top photo), and

we saved up until we could afford a fuel-efficient

wood stove.

Our current model burns so clean that I can't actually see smoke

once the initial water vapor is driven off. I had initially

reported our Jotul's emissions rate as 5.2 g/hr, but the EPA

website seems

to list it even lower, at 3.4 g/hr.

To help explain my take

on the matter, let's go back in time. Mark and I started out

with a monstrous

wood stove that spewed forth smoke (see the top photo), and

we saved up until we could afford a fuel-efficient

wood stove.

Our current model burns so clean that I can't actually see smoke

once the initial water vapor is driven off. I had initially

reported our Jotul's emissions rate as 5.2 g/hr, but the EPA

website seems

to list it even lower, at 3.4 g/hr.

Am I glad we saved up for the fuel-efficient wood stove?

Very much so! Would I have skipped the intermediate,

polluting step and gone right to the efficient stove? Well,

we couldn't have afforded the efficient stove when we got the

inefficient stove, so knowing what we knew then (not much), we

probably would have just bought an inefficient, used wood stove

locally. It's not as if the EPA is going to send out officers to

look for illegal wood stoves --- their regulations are only going

to be enforced by insurance companies --- so poorer people will

likely keep buying whatever they want used if they can't afford

insurance. I've heard from various people locally that you

can't really insure a home heated solely by wood anyway (at least

around here) unless you install a heat pump and say that's your

primary heat source, so this might not make a big difference.

How do we feel about

the polluting effect of our current wood stove? Pretty

good. I don't have data to back this up, but I estimate the

minimal amount of particulates emitted by our wood stove is so

well dispersed before the smoke hits our nearest neighbor (roughly

a half mile away) that the effects are negligible there.

Here at the source, I figure we're still breathing cleaner air

than the average urban or suburban American, and we have the

benefit of being able to harvest our own fuel sustainably at a low

cost, enjoying radiant heat and wood chopping, and not worrying

about lack of heat during our sometimes-extended power outages.

How do we feel about

the polluting effect of our current wood stove? Pretty

good. I don't have data to back this up, but I estimate the

minimal amount of particulates emitted by our wood stove is so

well dispersed before the smoke hits our nearest neighbor (roughly

a half mile away) that the effects are negligible there.

Here at the source, I figure we're still breathing cleaner air

than the average urban or suburban American, and we have the

benefit of being able to harvest our own fuel sustainably at a low

cost, enjoying radiant heat and wood chopping, and not worrying

about lack of heat during our sometimes-extended power outages.

In the end, I think the EPA rule is a good thing. The first

place I part company with libertarians is the environment --- even

though our government does a poor job of protecting our earth, I

think we'd do an even worst job without its oversight. Since

the current rule will likely push at least some people who can

afford it to change over to a more efficient stove, while not

unduly harming people who can't afford to make the switch, it

seems like a win-win. I'm sure many of our readers will feel

very differently about the topic, though, so feel free to comment.

We're lucky to have a stone

quarry only 8 miles down the road.

I got a Chevy S-10 truck load

today for 13 dollars.

Driveway repair will be the

theme for tomorrow.

As I wrote nearly a

month ago, two

of our hives have an absurdly low number of varroa mites, but a

three-day-sticky-board count averaged out to 29 mites per day in

the third hive.

Even that relatively-high mite  fall isn't so bad, but I've regretted it

before when I've let borderline hives go into winter --- they

often perish. So I decided to use one of safest methods of

mite control, treating the hive with powdered sugar.

fall isn't so bad, but I've regretted it

before when I've let borderline hives go into winter --- they

often perish. So I decided to use one of safest methods of

mite control, treating the hive with powdered sugar.

Scientificbeekeeping.com

has a fascinating

series of articles on the efficacy of using powdered sugar to

lower varroa mite numbers. The author, Randy Oliver, found

that 50% of the mites in a hive can be removed by adding half a

cup of powdered sugar per shallow (or a whole cup per deep) to the

top box. The sugar falls down through the cracks to coat all

of the bees present, making it tough for mites to keep their

footing. The bees do have to work hard that first day,

grooming off powdered sugar (and mites), but the intrusion is

worth it if you're worried about your mite population since so

many mites fall through the screen in the bottom of the hive and

perish..

In addition to the

intrusiveness of the powdered sugar technique, there is another

downside to using powdered sugar as your sole mite-control

measure. Oliver explains that powdered sugar only removes

the mites currently on bees, and since mites carry out part of

their life cycle inside capped brood, you won't really do much

good if the bees are actively raising young at the time of

treatment. However, when colonies are letting populations

drop to get ready for winter, powdered sugar can really decimate

mite populations. Oliver concludes that properly-timed

powdered sugar applications (plus screened bottom boards) might be

all the treatment you need if you're raising bees that have been

bred to be mite-resistant.

To return to my own

experiment, I smoked our bees gently just to make sure they

wouldn't fly up into the powdered sugar, then dusted the top of

the hive with 2.5 cups (half a cup per Warre hive box). The

sugar that built up on the top bars was easy to push back into the

hive using the bee brush.

Immediately after

dusting the hive, I could see bees out on the porch licking up

powdered sugar. Although powdered sugar is harder for bees

to consume than sugar water is, our ladies are still able to

convert some into food, and, eventually, honey. So the

varroa mite treatment doubles as a quick feeding boost to lightly

prop up fall stores.

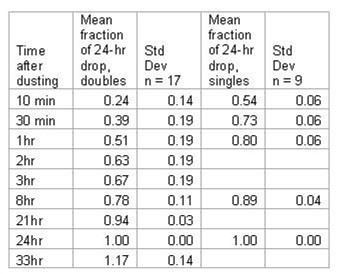

The other bonus of the

sugar treatment is that it gives you a more accurate portrayal of

probable mite levels in the hive, compared to the

potentially-problematic sticky-board counts. Just put the

bottom board in before treatment, take it out a timed interval

later, and count mites. The chart to the left comes from Oliver's

second article about powdered sugar, and the second column

shows what fraction of the total daily mite drop comes during

various intervals right after treatment. I counted 26 mites

on the bottom board of our hive 30 minutes after dusting with

sugar, so if we assume 39% of all the mites that were going to

fall that day had already hit the bottom, and that the treatment

will remove 50% of the mites in the hive, I get a population

estimate of 133 mites in the hive pre-treatment.

The other bonus of the

sugar treatment is that it gives you a more accurate portrayal of

probable mite levels in the hive, compared to the

potentially-problematic sticky-board counts. Just put the

bottom board in before treatment, take it out a timed interval

later, and count mites. The chart to the left comes from Oliver's

second article about powdered sugar, and the second column

shows what fraction of the total daily mite drop comes during

various intervals right after treatment. I counted 26 mites

on the bottom board of our hive 30 minutes after dusting with

sugar, so if we assume 39% of all the mites that were going to

fall that day had already hit the bottom, and that the treatment

will remove 50% of the mites in the hive, I get a population

estimate of 133 mites in the hive pre-treatment.

Actually, I think I

probably didn't use quite enough sugar, since Warre hives are so

tall compared to Langstroth hives. So, perhaps my sugar

treatment is only going to remove 25% of the mites from the hive,

providing a pre-treatment estimate of 267 mites in the hive

instead of 133. Either way, that's pretty low, suggesting I

probably didn't need to dust the bees with sugar, but the

treatment is unlikely to have done much harm, and potentially will

help the bees survive the winter since they won't have so many

parasites sucking their blood.

Actually, I think I

probably didn't use quite enough sugar, since Warre hives are so

tall compared to Langstroth hives. So, perhaps my sugar

treatment is only going to remove 25% of the mites from the hive,

providing a pre-treatment estimate of 267 mites in the hive

instead of 133. Either way, that's pretty low, suggesting I

probably didn't need to dust the bees with sugar, but the

treatment is unlikely to have done much harm, and potentially will

help the bees survive the winter since they won't have so many

parasites sucking their blood.

If I remember, I'll

run another sticky-board count in a few days to see what varroa

mite levels are like post-treatment. I haven't decided yet

whether I should treat the low-mite hives, or leave them alone to

go into winter without the day of trauma.

This new bucket configuration

allows me to haul 30 gallons of gravel.

Next would be to dream up

some easier way of lifting each bucket from its crate.

Maybe some kind of crane

structure with a hand cranked winch.

We made a mistake

this year and left our straw

cache out at

the parking area under a tarp. It's been so wet that there

was no easy time to haul the bales in, so we figured we'd just get

them as we needed them. Unfortunately, the wind blew the

tarp back and got most of the bales damp, so they're now extremely

difficult to haul (even though Mark's still carrying through with

the endeavor).

On the plus side,

those slightly-decomposing bales seem to have provided the perfect

habitat for baby black rat snakes. Mark found some eggs

between two bales in September, and thrust them further into the

pile since he didn't know what else to do with them. The

eggs must have hatched in the interim, because two little snakes

turned up in the straw Thursday. Kayla isn't a fan of

snakes, and wasn't terribly thrilled to have her mulching job

include snake patrol, but I think even she could tell that these

guys are too cute to really be afraid of.

Actually, I thought,

at first, that this was an entirely new species for our farm,

until Kayla keyed the snake out in my field guide and discovered

that baby rat snakes look nothing like adults. Who would

have thought this prettily-patterned snake is going to be solid

black above by the time it gets two feet long?

(By the way, Kayla,

you guessed right --- these guys did just hatch.

Newly-hatched black rat snakes are twelve inches long. Hard

to imagine all that length folded up into a two-inch egg!)

This is the second Warre

hive quilt cover I've attached to a box.

I used pieces of thin plywood

instead of furring strips to secure the fabric.

I put off answering

Karen's question because I kept thinking I'd posted about our

average day before, but I couldn't seem to find the page.

So, I apologize if this is a repeat....

After a couple of

years on the farm, Mark and I came to a compromise we could both be happy

with about working hours --- 9 to noon, then 1 to 4. During

warm weather, we spend the first chunk working outdoors and the

second chunk on money-making tasks (swapping the order in the

winter). You hear about the outdoors portion of our day all

the time, and can probably guess that the other half consists of

making chicken waterers (both of us, or

sometimes various helpers), mailing those waterers (Mark), writing (me), and keeping our online empire running

(mostly me).

Of course, there are

also the parts of the day that don't really count as work (if any

of it does, which is up for debate). I start half an hour

earlier than Mark does so I can feed the chickens and walk

Lucy. Mark takes the afternoon shift, bringing in the

eggs and giving Lucy another training walk after "work."

Cooking doesn't count as work (unless there's a lot of excess to

be preserved), and neither does blogging.

No matter how you

divide up work and non-work chores, Mark and I have a lot of

leisure time to use as we wish. Mark has been enjoying a

post-lunch nap most days lately, and I've always got a book on

hand to fill those free hours (if Huckleberry doesn't need extra

spoiling). Excess time never seems to be a problem, though

--- I would be quite happy if days were 48 hours long --- which I

guess is a good sign that both the work and non-work parts of our

day are fulfilling. I hope you can develop a structure that

feels the same!

I've switched from a water

hose material to nylon rope for training

high density apples.

The nylon is more flexible

and was easier to install.

We had such a strong

late-summer nectar flow, I neglected to check the bees in September.

Usually, that's when I decide if I need to start feeding to ensure

the colonies make it through the winter, but how could they need

more honey when I'd fed the two weaker hives all spring and early

summer, and the wildflowers had taken care of the early fall?

Well, I was wrong.

The barn

swarm was in

the worst shape, having only colonized one super. I knew

that the colony was a gamble since they got such a late start, but

it was still a shock to see the whole hive empty except for six

small frames partly full of brood, pollen, and honey. I

don't know what I could have done differently, except maybe if I'd

kept feeding through the nectar flow, and chances are this hive

will perish over the winter. Still, I'll help them as best I

can, removing the empty brood box, putting the colonized super on

the bottom and the empty super above them just in case they want

the space, then cobbling together a Warre-style

quilt out of an extra super to provide insulation on top of

the hive. And I'll feed as long as they'll take it.

Well, I was wrong.

The barn

swarm was in

the worst shape, having only colonized one super. I knew

that the colony was a gamble since they got such a late start, but

it was still a shock to see the whole hive empty except for six

small frames partly full of brood, pollen, and honey. I

don't know what I could have done differently, except maybe if I'd

kept feeding through the nectar flow, and chances are this hive

will perish over the winter. Still, I'll help them as best I

can, removing the empty brood box, putting the colonized super on

the bottom and the empty super above them just in case they want

the space, then cobbling together a Warre-style

quilt out of an extra super to provide insulation on top of

the hive. And I'll feed as long as they'll take it.

The two Warre hives

are in better shape, but don't have as much honey as I'd

hoped. In fact, the hive I

dusted with powdered sugar this week had three empty boxes

(which I removed)! I had wondered how a hive we started as a

package this spring could have used up so many boxes so fast, but

the boxes on top were full, so I kept adding more. With only

two boxes colonized, I'll start feeding them to ensure they have

enough honey. Meanwhile, our oldest hive, started as a

package in spring 2012 then losing half their workers to a swarm

in spring 2013, never made it into their third box either, so I'll

feed them as well.

The two Warre hives

are in about the same state our

single Warre hive was in last fall, so I'm not terribly

concerned about them making it through the winter (although

feeding until it gets cold won't hurt). And the word on the

street is that all the rain made this a tough year for bees in our

area, so I guess it's not so bad I'm stuck feeding them

again. Maybe next year they'll finally get off the dole and

make some honey for me?

This is the second time this

year we've had to break out the trail

camera.

Deer damage started a few

nights ago, and so far no photographic evidence.

Anna moved the camera, so

hopefully if she comes back we'll record the moment and location where

the midnight invader is getting over the fence.

We had a minor

deer incursion Thursday night, the second

one this year.

Once again, the problem was a sagging fence --- in this case,

honeysuckle had bowed the fence down to the point where a deer

could probably step right over it. I'd known about the

danger spot, but figured it was unlikely a deer would walk up the

steep hillside below and enter our farm right outside our back

door. I was wrong.

Luckily, Mark's

hard-core deer-deterring actions meant the deer didn't come back

the next day, and has hopefully moved on to easier pickings.

In addition to tearing the vines off the problem fence, Mark added

two cedar posts to the problem area so he could extend the fence

up another four feet. Next, Mark plugged back in the deer

deterrents

(silent for the last couple of months) and moved one right in

front of the incursion spot.

Meanwhile, I covered

up all the strawberries with plastic trellis material. This

stuff really comes in handy for everything from deer fencing to

cucumber and pea trellises, and it also makes it

tougher for a deer to really munch on their favorite plants.

Granted, the deer already ate half the leaves on four strawberry

beds, but shutting the barn door after the horse is gone works

with plants since they regrow (as long as they don't get nibbled

again).

Our last step was to

hook up the game

camera to make

100% sure the deer doesn't come back (or, if it does, to find out

where its new entrance is). The only thing we caught on

camera, though, was me --- taking Lucy for a walk, bringing in the

laundry, and just peering into the lens. I think the words

going through my head were "Does this thing still work?"

We used an old Christmas tree

stand to mount a new EZ Miser chicken waterer.

It only took a few minutes to

attach a piece of decking board to an 18 inch 2x4.

A scrap chunk of 2x4 at the

bottom helps to even it out.

Despite the fact

that we basically live in a swamp, we don't have a terrible bug

problem. Yes, at dusk, the no-see-ums come out, there's a

mosquito now and then, and the deer flies get bad down in the

floodplain during the dog days of summer. But, generally,

Mark and I can work outside without feeling bombarded by

bloodsuckers.

Despite the fact

that we basically live in a swamp, we don't have a terrible bug

problem. Yes, at dusk, the no-see-ums come out, there's a

mosquito now and then, and the deer flies get bad down in the

floodplain during the dog days of summer. But, generally,

Mark and I can work outside without feeling bombarded by

bloodsuckers.

The dragonflies, I'm

sure, deserve a lot of the bug-control

credit, but so

do the bats. That's why Mark and I were so happy to have a

visitor spending a sunny day hidden above the porch rafters.

"Wouldn't it be nice

if we made a bat box and collected the guano underneath?" Mark

mused. My very-limited experience with bat boxes involved

watching how the boxes around the nature center where I worked as

a high school student always stayed vacant, and my boss telling me

that he'd never seen a bat box used. But the idea is so good, I thought I'd ask

around --- have you ever seen a bat box with a no-vacancy sign out

front? If so, what was the bat box's design?

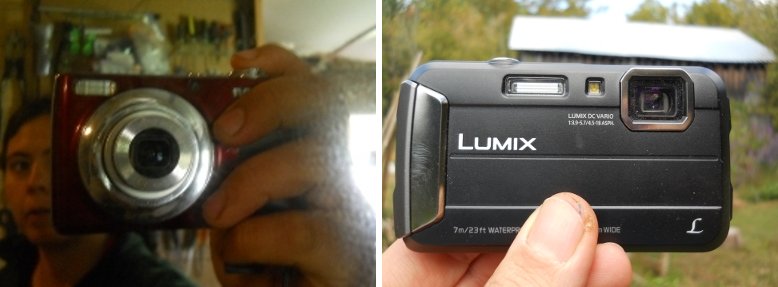

The Nikon

Coolpix L22 developed an

issue with the memory card door where a plastic piece is worn down to

the point of allowing the door to pop open during operations.

I opened that little door

every day for the last two years. It still works good with a piece of

electrical tape holding it shut, but not fun for everyday blogging.

Maybe I'll move it to the glove compartment of the car in case we're

driving and see Big Foot or something else worth taking a picture of.

My new blogging camera is the

Panasonic

Lumix DMC-TS25. It can

take pictures underwater, which means it has a beefier memory card door

that should hold up to heavy usage without breaking. Stay tuned for a

full report on how it's working out once I get a chance to use it a bit

more.

A few weeks ago, I caught

a stomach bug and spent a few days with absolutely no interest in

food. On our farm, I manage the larder and meals while Mark

does the dishes and grocery shopping, so without me on the job,

several figs and raspberries rotted on the vine. The waste

was extremely minimal, but it got me thinking about one of the

biggest hurdles non-full-time homesteaders face --- putting in the

daily time to make sure they pluck produce at its peak. That

thought set me pondering which fruit types are best and worst for

the true weekend

homesteader who only has two days a week to visit her

garden.

A few weeks ago, I caught

a stomach bug and spent a few days with absolutely no interest in

food. On our farm, I manage the larder and meals while Mark

does the dishes and grocery shopping, so without me on the job,

several figs and raspberries rotted on the vine. The waste

was extremely minimal, but it got me thinking about one of the

biggest hurdles non-full-time homesteaders face --- putting in the

daily time to make sure they pluck produce at its peak. That

thought set me pondering which fruit types are best and worst for

the true weekend

homesteader who only has two days a week to visit her

garden.

Even though I think

of them as productive and low work, I realized that most berries

wouldn't be appropriate for the true weekend homesteader.

Raspberries tend to mold in our climate if you go more than a day

(possibly two if it's sunny) without picking, and I discovered

that ripe figs (although not a true berry) won't last much

longer. Strawberries are probably in the fig category, while

blackberries are a bit more resilient and might manage if picked

only twice a week. Blueberries would thrive on this

treatment due to their firm skins that give you a long picking

window (although blueberries do fail the test of producing at a

young age, not requiring nitpicky soil treatment, and being easy

to propagate).

How about tree

fruits? Only our peaches and apples are producing so far, so

I can't really write from personal experience, but it seems like

(at least in a humid climate like ours) peaches require attention

a few times a week during the harvest season. Apples are

much more forgiving, and a weekend homesteader could easily pick

the bulk of his apple crop during one crisp Saturday, then eat

homegrown apples all week (or month, or winter). From what

I've seen elsewhere, I'd say pears are similar to apples (although

you do have to take them out of cold storage a few days before

eating to allow pears to fully ripen, so that takes a bit more

management). Plums are likely to be similar to peaches, but

I'm guessing a bit less prone to rot (so easier to ignore for days

on end).

How about tree

fruits? Only our peaches and apples are producing so far, so

I can't really write from personal experience, but it seems like

(at least in a humid climate like ours) peaches require attention

a few times a week during the harvest season. Apples are

much more forgiving, and a weekend homesteader could easily pick

the bulk of his apple crop during one crisp Saturday, then eat

homegrown apples all week (or month, or winter). From what

I've seen elsewhere, I'd say pears are similar to apples (although

you do have to take them out of cold storage a few days before

eating to allow pears to fully ripen, so that takes a bit more

management). Plums are likely to be similar to peaches, but

I'm guessing a bit less prone to rot (so easier to ignore for days

on end).

On our farm (as long

as I don't have a rare stomach bug), I actually prefer fruits in

the berry category since I like the daily harvest better than the

gushing influx of bushels of luscious orbs to be managed all at

once. (Not that the flood isn't exciting.) But if I

left the farm before sunup, returned after dark, and only had

Saturday and Sunday to tend my homestead, I'd stick to tree

fruits. How about you? Do you have any recommendations

for fruit types that can handle days of neglect and still provide

a bountiful crop?

The Cadillac

worm bins are doing

good...except for this one.

Clearly we should have put a

support brick in the middle for the front and back.

Maybe I can use the scissor jack to raise it up and slide a brick

in to fix it.

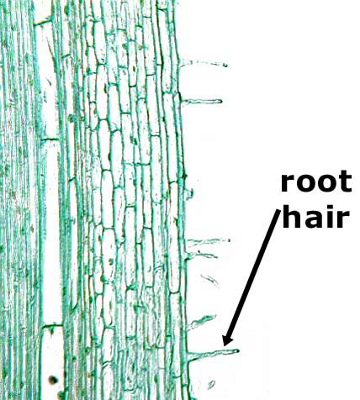

I've been reading a

lot of tidbits about root hairs over the last couple of

years. Various sources have explained that root hairs are

the only parts of a root that take up most nutrients. Others

add that root hairs are only formed on the tips of growing roots

and live for just two to three weeks. Presumably, that means

you should time your compost application for the periods when root

hairs are being actively formed.

Michael

Phillips

asserts that fruit trees go through cycles of root growth,

alternating with  shoot growth, so you

can expect your trees to be actively taking up nutrients primarily

in mid spring, late summer, and fall. Someone else (I think

it was Robert Kourik) explained that tree roots keep growing until

the ground gets below 40 degrees (if my memory serves). By

keeping the soil warm, a good autumn mulch can give your plant

extra growing time, and, similarly, fall-planting (in zone 5 and

warmer) gives trees a jumpstart on the year ahead.

shoot growth, so you

can expect your trees to be actively taking up nutrients primarily

in mid spring, late summer, and fall. Someone else (I think

it was Robert Kourik) explained that tree roots keep growing until

the ground gets below 40 degrees (if my memory serves). By

keeping the soil warm, a good autumn mulch can give your plant

extra growing time, and, similarly, fall-planting (in zone 5 and

warmer) gives trees a jumpstart on the year ahead.

But I felt like I was

missing a critical link in my understanding of root hairs.

For example, are those white roots in the photograph above (from a

black raspberry) root hairs? Wikipedia suggests not, saying

that root hairs are single cells elongating sideways away from the

main root, and are generally invisible to the naked eye. On

the other hand, since new root hairs are found on new roots, and

new roots are white, I suspect I can use color as a rough estimate

of where root hairs are present.

And can I take

Michael Phillips' assertion about seasonality to be true of all

perennials? I'm sure each species has its own cycle of root

growth --- perhaps the only way to know is to keep an eye out for

white roots in the few instances when I'm messing in the dirt

around my woody plants. If anyone has found a source with

data on root growth seasonality for the common fruiting plants,

I'd love to see it!

We got this Celeste fig

tree a year ago at Rose's discount store in St Paul.

No figs from it this year,

but the amount of growth is an indicator that it should continue to

thrive in our climate zone.

I'm afraid I've

finally found a fruit I really don't like. I used to think

the reason I had odd memories of pawpaws is because (after our

family moved away from the farm), Mom would drive us out in the

country to pick the fruits, and I always arrived carsick.

However, I've been watching a pawpaw along our driveway all

summer, waiting for it to ripen up, and when the first fruits hit

the ground, I took the rest home to taste. There were no

cars involved, so I definitely wasn't nauseous, but the fruits

weren't something I'll seek out again.

Internet descriptions

of pawpaw flavor range from banana custard to plain banana, mango,

papaya, and pineapple. I'm not sure I know what banana

custard tastes like, but I can tell you definitively that pawpaws

taste nothing like the other fruits, except maybe having a hint of

the unpleasant flavor you get really close to the skin of an

unripe mango or papaya. (I suspect many of the folks

describing pawpaws were confusing flavor with texture --- pawpaws

do have a texture about halfway between a mango and a banana.)

If I had to describe

the flavor of pawpaws, I'd say they're sweet (of course) combined

with a slightly bitter taste and an almost over-powering floral

odor that sets me off the fruit. Perhaps if I'd held my nose

while eating, I would have liked the taste better?

Granted, there are

different varieties of pawpaws, as with other kinds of

fruits. And it's possible some of the cultivated varieties

taste better. But I like my fruits to have at least some

tartness to them, and pawpaws fail that test. That's why my

second experiment was to mash the flesh up with some lemon juice

and honey, then add it to our raspberries and whipped cream.

I hate to say it, but that was even less tasty than the flesh we

ate plain, and I didn't mind when Mark picked the pawpaw off his

berries.

I'd be curious to

hear from anyone who's grown named varieties of pawpaws.

What varieties are you growing, and what do you think of their

flavor?

Pure-gas.org

is a list of ethanol-free gas stations in the U.S. and Canada.

The 2 stations that advertise

on their signs in Gate City are on the list.

I still want to do an ethanol

content test the next

time we are in that area.

Image credit goes to Casey Frederick.

Somewhere early in

life, I was told that fuzzy caterpillars can sting. Later, I

discovered that all caterpillars that turn into moths (instead of

butterflies) are fuzzy, but only a few sting. Yet, I kept my

distance anyway.

I finally got stung by a caterpillar for the

first (and second time) in mid September. This saddleback

caterpillar was hiding in the blueberries and I accidentally

brushed my finger against it while picking. The surprising

pain made me jump away and then forget about the caterpillar, so

the critter managed to sting me again a few days later when I came

back to finish harvesting that spot.

I finally got stung by a caterpillar for the

first (and second time) in mid September. This saddleback

caterpillar was hiding in the blueberries and I accidentally

brushed my finger against it while picking. The surprising

pain made me jump away and then forget about the caterpillar, so

the critter managed to sting me again a few days later when I came

back to finish harvesting that spot.

Luckily, the sting

wasn't very bad --- not worth spending decades avidly avoiding an

entire sub-order for. It felt like I'd walked through a

patch of stinging nettles, meaning the pain was intense for a

minute, noticeable for an hour, then quickly forgotten. (To

be fair, though, I have a high tolerance for stings.)

If you live in my

neck of the woods, you

can see all of our poisonous caterpillar species here. Like snakes, I figure it's worth

learning the few poisonous species so you'll know everything else

is harmless. Then you can start enjoying

the beautiful permutations of nature without worrying about your skin.

This post is to remind me when the Dungannon area solid waste center is open.

My parents had a

strict no-sugar policy when I was a kid, so we ate some unusual

desserts. One of my favorites was "golf balls," a

conglomeration of nuts, dried fruit. and fresh lemon that a family

friend came over and helped us make each Christmas in a

hand-cranked sausage grinder. I decided to try blending my

own version out of our home-dried fruit (and a few purchased

additions), and liked the result enough to share with you.

Here's the original

recipe, as best I can remember it:

- flesh from 1 coconut

- some amount of nuts, all kinds (probably largely pecans and walnuts)

- some amount of dried apricots, dried figs, and dried dates

(roughly equal parts?)

- 1 whole lemon

And here's my

homegrown alternative:

- 8.9 ounces dried Chicago Hardy figs

- 7.2 ounces dried white peaches

- 8 ounces dried dates

- 4.6 ounces English walnuts

- 1 whole lemon (seeds removed)

I ground everything

up, a bit at a time, in a food processor, then rolled the dough

into fifteen balls. Without apricots, the fruit balls

weren't as cheerfully orange, but the flavor felt richer (probably

because of the tartness of the peaches). I also observed

that the food processor made a chunky texture rather than a

blended whole, which has its own pros and cons. (I liked the

chunks, but kids would probably prefer the blended version.)

On the whole, I'm

happy with the experiment, although I might try again with coconut

taking the place of some of the nuts. (I didn't leave out

the coconut on purpose --- the one Mark bought for me was

moldy.) The fruit-and-nut balls make me think of a

vegetarian pemmican and are pretty healthy for something that

tastes like a dessert (145 calories per ball, 9% protein, with 15%

of your daily allowance of fiber).

Of course, Mark still

thinks this is one of my crazy family dishes, best avoided.

Maybe if I came up with a better name than "golf balls," he'd give

it another try. Want to help redub the dessert?

Four days and nights at

Pawley's Island South Carolina was a perfect vacation.

The beach is beautiful but we

started missing our mountains the last day.

Saw the 3D version of Gravity

and thought it was Awesome!

In Your

Money or Your Life, Joe Dominguez and Vicki Robin write that people who live

fulfilling simple lives shouldn't need a vacation. They may

be right, but the truth is that I seem to need a solid break

sometime in October between the rush-rush-rush of the growing

season and the gentler writing period of the winter. Some

years, a staycation does the trick, but in

other years --- like this one --- we seem to crave a more

solid break.

The best thing about

an away-from-farm vacation is how much it makes us appreciate our

everyday life. Coming home to a not-quite-frosted farm, with

newly-vibrant colors and the scent of fallen leaves in the air,

Mark and I both concluded we live in paradise.

How about you?

Do you feel the need for a vacation even if you live in paradise?

(Stay tuned for far

more beach photos than you care to see in this week's lunchtime

series.)

As Mark mentioned, we

snuck away last week to spend four nights on Pawleys Island, and

it was the best vacation we'd ever had. Rather than boring

you with our vacation pictures in one post, I'm going to split

them apart into an elongated lunchtime series and pretend that

makes them more interesting! In fact, I'm even going to add

tips about what made this vacation so perfect for us and pretend

it's educational! Pretty fancy, huh?

(In other words, it

won't hurt my feelings at all if you skip this and the following

only-quasi-homesteading-related (okay, not-really-related-at-all)

posts.)

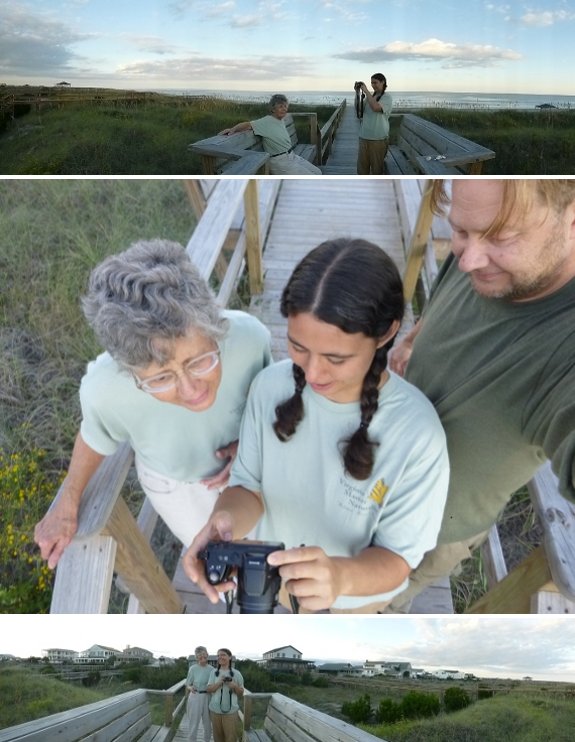

Perfect vacation tip #1: Start with

good company

We talked Mom into

coming to Pawleys Island with us. As Kayla said, "It takes a

pretty special husband to bring his mother-in-law on vacation"

(then she went on to add that she and her husband brought her

parents on their honeymoon). But, lest you think I'm cruel

and unusual, I should add that my husband is so special that

inviting Mom was his idea.

And I can't help feeling that Mom is

what made this vacation the best one ever. Mark likes to sit

still and watch the ocean, but I'm a relentless explorer, and it

was just more fun to explore with Mom's exuberance at my

side. In fact, Mom and I are so much alike that we

accidentally wore the same t-shirt for our group photo day ---

oops.

And I can't help feeling that Mom is

what made this vacation the best one ever. Mark likes to sit

still and watch the ocean, but I'm a relentless explorer, and it

was just more fun to explore with Mom's exuberance at my

side. In fact, Mom and I are so much alike that we

accidentally wore the same t-shirt for our group photo day ---

oops.

So, pretending this

post has actual merit for its non-family audience, your first tip

for building a perfect vacation is to start with good

company. Mom, Mark, and I made a perfect team, so fun was

had by all.

| This post is part of our Gratuitous Vacation Photos lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Anna asked me. "How can I

display my favorite sea shells so they won't get broken?"

"I guess I could glue them to

a display board, but there's not enough surface area".

The way I increased the

surface was to chisel away a groove for the bigger shells to sit in,

giving the extra surface area for the glue to bond with the bottom part

of the shells.

One of our first

years on the farm, Mark and I grew several different kinds of

winter squash and settled on butternuts as both the tastiest and

the most pest-and-disease-resistant variety. Ever since,

we've been a purely butternut farm.

But I love trying new things. So when

my movie-star neighbor offered me some of his homegrown squashes,

I had to give them a try. I've yet to cut into the pie

pumpkin he gave me, but I cooked up the blue hubbard into a

pie Sunday, and it was one of the best I've ever eaten.

But I love trying new things. So when

my movie-star neighbor offered me some of his homegrown squashes,

I had to give them a try. I've yet to cut into the pie

pumpkin he gave me, but I cooked up the blue hubbard into a

pie Sunday, and it was one of the best I've ever eaten.

Will we start growing

hubbard squash as a result? Well, there are several factors

to consider. If you're a seed saver, you have to think long

and hard before adding new squash varieties to your garden, but it

turns out that blue hubbards wouldn't be very tough for us to

integrate. Butternuts are Cucurbita moschata, summer squash are Cucurbita

pepo, and

blue hubbard is Cucurbita maxima, so I could grow all

three in the same garden without worrying about crosses.

(However, if you're more of a pumpkin person, some pumpkins do

cross with blue hubbard, as do winter marrow, turban squash, and

banana squash).

On the other hand,

since we use variety selection as our first line of defense

against squash

vine borers, we probably should skip the hubbards.

Butternuts are among the most resistant to vine borer damage, but

hubbards are so beloved by the insects that they are sometimes

used as a trap crop alongside rows of other types of squash.

Another downside of hubbards compared to butternuts is that the

hubbards are big --- even the smallest in my neighbor's collection

had enough flesh for 2.5 pies, and our small family does better

with the more minuscule butternut.

And, to be honest, I

think the reason our hubbard pie was so delicious is because I

added extra honey since the squash flesh wasn't as sweet as the

butternuts I'm more used to. You can read my

original butternut pie recipe here, and this is the new ingredient list we've

developed over the years:

Crust:

Crust:

- 0.5 cups flour

- 0.5 cups cocoa

- 0.25 cups sugar

- 0.5 teaspoons salt

- 7 tablespoons butter

- a bit of water

Pie:

- 2 cups baked winter squash flesh

- 1.5 cups evaporated milk powder

- 1.25 cups water

- 0.5 cups of honey (or add two tablespoons to that for a sweeter pie)

- 0.5 teaspoons salt

- 1 teaspoon cinnamon

- 0.5 teaspoons allspice

- 0.25 teaspoons ginger

- 2 eggs

Click on the link

above for preparation instructions, and enjoy!

Perfect vacation tip #2: Plan for immersion

Perfect vacation tip #2: Plan for immersion

When Mark, Mom, and I

decided to go on vacation together, we opted for Pawleys Island

since Mark had gone there as a child. "I always wished we'd

rented a house right on the beach," he sighed. Even in the

off-season, beach-front rentals are more expensive, but we decided

to splurge and give Mark his dream...and I was so glad we did!

Being right on the

beach meant we could watch the ocean from the screened-in

porch, or wander down the boardwalk several times a day for a walk

or a swim. If I'd had to get in a car, I probably would have

spent more time lazing around the house, but I was so engrossed by

the ocean on this trip that I barely read one fiction book and

didn't even crack Small

is Beautiful,

which I'd brought along for deeper-thought periods. In

contrast, on other vacations of this length, I've often gone

through one or two non-fiction books and three to five fiction

books.

Being right on the

beach meant we could watch the ocean from the screened-in

porch, or wander down the boardwalk several times a day for a walk

or a swim. If I'd had to get in a car, I probably would have

spent more time lazing around the house, but I was so engrossed by

the ocean on this trip that I barely read one fiction book and

didn't even crack Small

is Beautiful,

which I'd brought along for deeper-thought periods. In

contrast, on other vacations of this length, I've often gone

through one or two non-fiction books and three to five fiction

books.

(You'll start to

notice that each perfect facet of this trip was dreamed up by

Mark. Hmmmm.)

In case you're curious, we rented Knox

Station for

four nights. It was fancier than we needed, but was a

perfect fit for our family.

Being up on stilts gave us perfect ocean views, and Mom only

stumbled on the stairs once when I made her walk down them in the

dark just before dawn so she wouldn't mess up her night vision for

sunrise. As an added bonus, the bend in the stairs smelled

just like my grandmother's attic, so I thought of that deceased

relative every time I passed by.

So, to return to the

point, if you can afford it, try to find a vacation spot that

really immerses you in what you came to see. Or, maybe the

moral is really "Pay attention to your husband"?

| This post is part of our Gratuitous Vacation Photos lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We took Lucy to the vet today

because she had a swollen cheek.

The doctor thinks it could

have been a snake bite, most likely a Black Rat snake.

Antibiotics and an extra Milk

Bone should have her feeling better in no time.

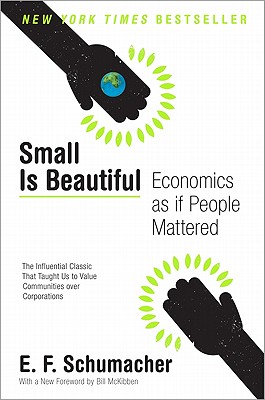

Several readers recommended that I read Small

is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered, by E.F. Schumacher, so

I figured I'd give it a try. Unfortunately, I wouldn't

recommend this book to most of you. I can handle the

academic tone (although sometimes the author seems to be

purposefully adding density to his writing), but none of the

information in the book is useful to the average homesteader.

Several readers recommended that I read Small

is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered, by E.F. Schumacher, so

I figured I'd give it a try. Unfortunately, I wouldn't

recommend this book to most of you. I can handle the

academic tone (although sometimes the author seems to be

purposefully adding density to his writing), but none of the

information in the book is useful to the average homesteader.

The trouble is that,

despite the title, this is a book about global-scale problems and

solutions. Schumacher focuses on topics like aid to poor

countries, rather than (as I was hoping) on ethical ways to run a

home business. In addition, the anti-science, pro-religious

sentiment was hard for me to stomach.

In the end, I have to

conclude that Schumacher and I have a major difference of opinion

about how the average person does good. Although I vote, I

tend to believe that someone like me can't really impact global,

national, or even state policies, and if I want to make change, I

have to start in my own life and lead by example.

Schumacher, on the other hand, finds value in philosophizing about

large-scale changes that would make the world a better place, so I

assume he feels that he can actually take part in bringing those

changes about.

But maybe I missed

something? I'll be the first to admit that the social

sciences are my least-favorite subject, and my eyes glaze over

pretty quickly just from the mannerisms of writers in that

field. So, for those of you who have read and enjoyed Small is Beautiful, I hope you'll leave a comment telling me why I'm

wrong, and why this book is important for every homesteader to

read.

Perfect

vacation tip #3: Make friends

Perfect

vacation tip #3: Make friends

Every time we drove

off the island, fishermen lined the causeway...and one of them had

feathers. It was fun to see the causeway egret every time we

passed by, and even more fun to get cooking advice time after time

from the ex-car-salesman behind the fish counter in the

supermarket. (These pleasant inhabitants even made up for the

excessively-surly waiter the one time we went out to dinner.)

If you don't make

friends easily, it's possible the universe will even plop some

friends down in your lap. Despite the fact that none of

us had discussed our vacation plans beforehand, it turned out

that our next-door neighbors on the island consisted of some

of our favorite folks from back home!

If you don't make

friends easily, it's possible the universe will even plop some

friends down in your lap. Despite the fact that none of

us had discussed our vacation plans beforehand, it turned out

that our next-door neighbors on the island consisted of some

of our favorite folks from back home!Our movie-star neighbor, my ex-boss from the non-profit, my first garden mentor, and a homesteader we'd been wanting to get to know better just happened to rent the neighboring house for the same days we did. What are the chances of that?

I didn't manage to take any pictures of our human neighbors, but we had fun catching up, making an audition tape with our movie-star neighbor, and building a sand monster with our homesteading friend. Having neighbors we knew turned this from a four-star to a five-star vacation!

| This post is part of our Gratuitous Vacation Photos lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The cinder

block stepping stones are

still in place after 2 years.

A set of stairs for getting

down the sloped side easier might be our next creek crossing

improvement.

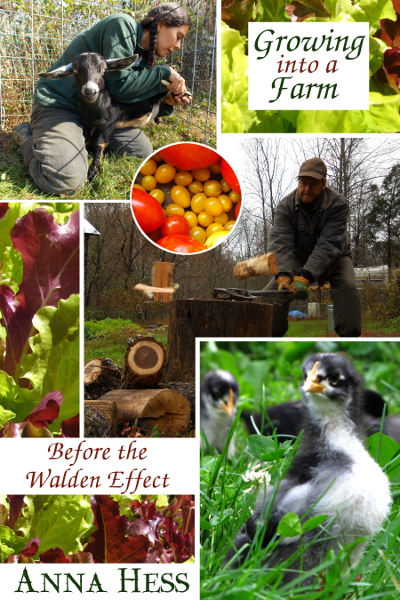

I promised

you all something entirely different for my next ebook, but

the truth is that I got sidetracked into first finishing a project

I'd started this spring. With the working title Walden Effect: The Early Years, this is a fluffy little book about falling

in love with the land and with a man at the same time. I've

excerpted a bit of the beginning below, but before I lose my

hardcore readers, I hope you'll stick around long enough to

suggest a better title. Title suggestions from our readers

turned Trailersteading into a bestseller, and I

suspect you can come up with a much better title for this ebook as

well. Ideas?

My new neighbors were

perhaps ten years older than me --- in their mid

thirties --- and were clearly bamboozled by this young woman who

planned to move into a southwest-Virginia tract of remote

countryside

by herself. Even getting to my old house required a

half-mile

trek through swamp and across a creek that sometimes flooded over

my

head. And now I didn't seem willing to come down off the

roof to

greet them properly. In part, my hesitance was due to being

tied

to a tree on the other side of the house by a rope around my

waist, but

mostly I was just embarrassed because I'd caught the seat of my

pants on

a nail about an hour ago and had heard a loud rrriiiip. No way was my

introduction to the neighbors going to involve exposed underwear.

My new neighbors were

perhaps ten years older than me --- in their mid

thirties --- and were clearly bamboozled by this young woman who

planned to move into a southwest-Virginia tract of remote

countryside

by herself. Even getting to my old house required a

half-mile

trek through swamp and across a creek that sometimes flooded over

my

head. And now I didn't seem willing to come down off the

roof to

greet them properly. In part, my hesitance was due to being

tied

to a tree on the other side of the house by a rope around my

waist, but

mostly I was just embarrassed because I'd caught the seat of my

pants on

a nail about an hour ago and had heard a loud rrriiiip. No way was my

introduction to the neighbors going to involve exposed underwear.Since the nearest town is home to only 300 people, I'm sure word of my eccentricities got around quickly. But it didn't matter because I nearly gave up on my homesteading dream six months later, only to rekindle the spark when my husband-to-be, Mark, walked into my life. Fast forward ahead five years and Mark was being invited to sit down on the coveted stool in the locally-owned hardware store and chat for a while --- a sure sign of being accepted by the community. At long last, I knew my craziness had been overlooked in favor of my husband's quiet persistence.

That summer day in 2004, though, I was still alight with the joy of owning a farm the way I'd dreamed about since childhood. And now, as I write this nearly a decade after purchasing that farm, I'm once again in love, this time with both the farm and with the husband who made my dream possible. So this is a love story in three parts about how I ended up with much more than I bargained for, and grew beyond the person I thought I'd be.

(Stay tuned for more

of this unnamed book in a week or two.... In the meantime, you might enjoy this

profile Everett recently wrote about us on his blog.)

Perfect

vacation tip #4: Go with the tides

As I'll mention in a

later post, we did go on a few real excursions as part of our

vacation, but mostly we just drifted in the day and ocean's

rhythms. Mom and I seemed to naturally wake with (or just

before) the sun, allowing us to take a stroll up the beach as the

sun rose.

Low tide came in the

early morning, so dawn turned up shells fresh for the

picking. Mom and I were sometimes on the beach before prime

shell-picking time, when dog walkers went out in the

near-dark. By the time we reached the north end of the

island, where the creek behind created an extended shallow area,

there was enough light to pick up broken sand dollars and whole

sea urchins. (We even saw a living sea urchin in the shallow

water our first night there!)

When my stomach

started to growl, the sun was up and the coffee walkers were on

the beach, strolling with mugs in hand. Later, we'd come

back to the beach for a quick swim at high tide.

I make it sound linear and regimented, but

the best thing about our beach combing is that it wasn't

either. Only on the last day did I realize that others were

planning their day around the perfect shelling times. Using

Mom's whimsy as a guide, I squashed my Type A need to turn up

perfect shells, and instead found beauty in the colors and

textures of fragments.

I make it sound linear and regimented, but

the best thing about our beach combing is that it wasn't

either. Only on the last day did I realize that others were

planning their day around the perfect shelling times. Using

Mom's whimsy as a guide, I squashed my Type A need to turn up

perfect shells, and instead found beauty in the colors and

textures of fragments.

On our last day, I

felt a twinge of regret that I hadn't done this or that, but then

I realized that I vastly preferred to go with the tides.

After all, it's better to be thoroughly in the moment than to do

it all.

| This post is part of our Gratuitous Vacation Photos lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We're still harvesting

figs from the Chicago

Hardy.

Meanwhile, the figs

we started from cuttings this spring are waist-high and are

starting to bloom.

Maybe that means next year

we'll get to taste Dwarf, Celeste, and Black Mission?

Lion's mane mushroom

has now made it onto my list of delicious and safe fungi to

wildcraft (along with morels

and oysters).

Despite the fact that there are at least three species in the

genus Hericium, all are edible, and the shaggy white mane makes

these mushrooms tough to confuse with anything else. You

might want to stick to the scientific name, though, since  common names are variable and include Bearded

Tooth, Hedgehog, Satyr's Beard, Bearded Hedgehog, and Pom Pom,

along with Lion's Mane.

common names are variable and include Bearded

Tooth, Hedgehog, Satyr's Beard, Bearded Hedgehog, and Pom Pom,

along with Lion's Mane.

How about

flavor? The internet reports that lion's mane mushrooms

taste like lobster, but even though I'm not a seafood fan, I

thought they were delicious. Mark (who loves seafood and who

reports that only the texture reminded him of lobster) agreed,

noting that lion's manes are midway on the delectability scale

between oysters and shiitakes. (Actually, some oyster

mushrooms can be as good as shiitakes, but the flavor tends to be

less dependable, so Mark rates them lower.)

I'm actually

surprised I hadn't stumbled across this distinctive edible before,

but I suspect the issue is that I'm a swamp girl and the lion's

mane likes harder wood, like oaks, which tend to grow in drier

forests around here.

Wednesday, I found two lion's mane mushrooms popping out of a

huge, fallen oak that came down in our parking area last

summer. Now I really, really want those delectable, rotting

logs for my forest garden. Too bad they're at least two feet

in diameter and each round weighs a ton....

Perfect

vacation tip #5: Take lots of pictures, then turn off the camera

Mark, Mom, and I all

love taking photos (and the photos in this lunchtime series are by

all three of us).

We took tons of

photos during our vacation, but I also left my camera behind on

purpose at certain times.

Sure, I missed some

stunning shots, but I was even more present right where I was

without a camera to mediate between myself and the world.

I guess the lesson

from this post is the same as from the last --- being in the

moment is worth the price.

| This post is part of our Gratuitous Vacation Photos lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Anna put the first quick

hoop of the season up today.

The pay off will be fresh

lettuce in November.

I've found that being obsessive about oral

hygiene is worth it. The expense aside (and a trip to the

dentist is always pricey), who wants the pain and suffering of a

filling (or worse)? That's why I always ask my dentist if

there's any more preventative care I can add to my routine, and

have come up with the following complex daily regimen:

I've found that being obsessive about oral

hygiene is worth it. The expense aside (and a trip to the

dentist is always pricey), who wants the pain and suffering of a

filling (or worse)? That's why I always ask my dentist if

there's any more preventative care I can add to my routine, and

have come up with the following complex daily regimen:

- Mornings I brush with an electric

toothbrush (better for the gums), then use both a

Listerine-type mouthwash (to kill germs, although I want to

research this more since I read recently that this might be a

bad idea, akin to killing off your good gut bacteria) and an

ACT-type mouthwash (for fluoride, since our well-water is

fluoride-free, and I'm willing to swish with fluoride despite

the potential dangers of drinking it)

- Evenings I floss, and brush

But when I went to the

dentist Wednesday, I reported I'd felt a little twinge in one

tooth recently. Did I have a cavity?

"Did you just start

using a whitening toothpaste?" the hygienist asked. Well,

yes, I guess I did. She explained that baking soda and any

other additives in toothpaste can cause your gums to recede since

the chemicals irritate the skin in your mouth. My hygienist

always recommends the plainest toothpaste you can find, but one

that contains fluoride.

My dentist came in then

and added in her two cents. Since I'm already using a

fluoride mouthwash, she doesn't see why I need to use toothpaste

at all. The mechanical movement of the brush is what cleans

your teeth --- toothpaste just gives you that minty-fresh breath

(and a dose of fluoride).

This is the best dentist

I've ever had, so I'm inclined to trust her judgment. And

who doesn't want to save $12 a year on toothpaste?

Here's hoping that at my next annual checkup, I'll once again be

cavity-free.

Keeping your

chickens healthy starts with clean water.

Civil War soldiers, corn meal machines, clogging, and apples all combine into a wonderful Saturday morning outing.

It's been about five

months since I've eaten a significant amount of store-bought

fruit, and when the Virginia

Beauties finally ran out last week, I went into

withdrawal. (Remember, I'm a fruit snob and think

grocery-store fruit, for the most part, is insipid and barely

worth eating.) We used to have a fruit stand which provided

fruit a notch above the grocery store (if not up to my exacting

standards), but the fruit stand didn't open up this year, so we'd

need to drive over an hour round trip to find moderately-edible

fruit. Or so I thought until I remembered that the little

town twelve miles away had opened up a farmer's market a couple of

years ago.

The first thing I saw upon entering the farmer's market was apples

--- jackpot! I browsed through all the vendors and ended up

selecting at least a few apples from each of three sellers.

I've yet to taste the Virginia Beauties from the lady to the left

(I got a pound, curious to see if they taste at all like my

homegrown morsels), but have already sampled two kinds of Winesaps

and an Arkansas Black. The latter is a milder apple than I

usually like, but I'm curious to see how long it will last in

storage (reputedly "forever") and whether the apple-grower is

right when he says the flavor will improve over time.

The Winesap

comparison was more interesting. The guy shown above sold us

both Winesaps and Arkansas Blacks, both of which he grows

conventionally (with sprays). And the apples did look

beautiful! But in terms of flavor, they merely matched what

you'd find at a moderate-to-good fruit stand.

In contrast, the

Winesap apples shown at the top of this post came from an

old-style organic farm, meaning that the standard-sized apple tree

had been there longer than the farmer had owned the land, and that

all he did to the tree was to pick the fruit. Although

smaller and less aesthetically appealing than the sprayed apples,

these old-style Winesaps were delectable and I wish I'd bought

more than one of the $5 baskets pictured. They nearly

matched the flavor of my homegrown Virginia Beauties.

I plan to put our

bushel-plus of apples in the fridge

root cellar and eat to my heart's content for at least the

next month. In the meantime, I clearly need to put more

thought into fruit that does well in winter storage since the more

summer fruit we grow, the less inclined I am to go back to bought

offerings after our homegrown stores run out. Some of the

slack will be taken up by our pears and Virginia Beauty as they

come into their prime, but Mark and I are quite frugivorous and

could probably use some more winter keepers.

Three nesting

boxes...yet we still have

a renegade hen who flies over the fence to lay her egg.

Wing clipping is a whole lot

cheaper than higher fences.

I decided to pick the

last of our tender vegetables (and figs) in preparation for the

frost, and even though it didn't (quite) freeze over the weekend,

I think it was a good decision. Chances are our first frost

will come sometime this week, so I didn't lose much ripening time

by my preemptive action.

I also treated myself

to the first fire of the winter since the trailer was a chilly 43

when I woke up Sunday morning. That means I also had to

admit our days of living on the porch are severely numbered, so I

cheered myself up about the move inside by cleaning all the

windows. It's astonishing how different indoors life is when

you can peer out through clean glass into the wider world.

Nearly as good as life on the porch...at least once you add in a

warm fire and a happy cat.

Perfect

vacation tip #6: Plan good excursions, but not too many

When we decided to go

to Pawleys Island, I started researching area attractions and soon

came up with a short list of half a dozen places I'd really like

to visit.

But when it came

right down to it, I knew we'd want to spend most of our time on

the beach, so I narrowed our main excursion down to one ---

Brookgreen Gardens. (We also made a few forays to the

grocery store, took in a movie, and stopped at the library, book

store, and Audubon store. Oh, and Mom wanted to go to the

consignment shop to get another sweat shirt.)

Having one major excursion in the middle was perfect. Our

first vacation day was a "sea day" in which we spent all of our

time at home or at the beach, so by our second day we had plenty

of energy to walk through the sculpture-and-botanical garden.

We were stunned by the live oaks and their attendant epiphytes

(Spanish moss and resurrection ferns). And I was

particularly taken by the way the landscapers had worked with

textures and designs that showcased the strengths of each

sculpture.

I highly recommend

this particular outing to anyone interested in plants and/or

art. Vastly better than a museum!

(More gratuitous

photographs. Plus, doesn't the trellis above look very

useful if you wanted to grow kiwis?)

Perfect

vacation tip #6.5: Don't try to do it all

Perfect

vacation tip #6.5: Don't try to do it all

As the leader of this

excursion, though, I made one mistake --- I dragged my compatriots

past the formal gardens to check out the zoo. I wanted to

learn which heirloom livestock were historically used in the area

(which I'll post about eventually on our chicken blog).

But we ended up footsore and saddened by the caged animals.

Mark and I figured that the livestock would be much healthier and

happier if they were rotationally grazed on the vast lawns, and

the grass would probably be greener there too.

So, my corollary

piece of advice for this post is to pay attention to your energy

levels and not to go see the otter exhibit just because the

visitor center lady said it was not to be missed. If you

don't feel like it, miss it.

| This post is part of our Gratuitous Vacation Photos lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

A wheelbarrow of dried walnut got our firewood splitting season off to a fine start.

The first fall frost

of 2013 came just a day later then I'd

expected...

...and with it came

blue skies! We haven't seen much of these for the last six

months or more, and I'd forgotten how beautiful the world is in

direct sunlight. I was starting to think we'd accidentally

moved to the Pacific Northwest.

As a side note

(assuming you were hoping to get a kernel of information from this

post), I didn't realize until I moved to the farm and started

monitoring frosts how important cloud cover is to nighttime

temperature. A cloudy day tends to be cooler, but around

here a cloudy night tends to be warmer because the clouds trap

heat close to the earth's surface. So I guess the frost and

blue skies were related after all.

Perfect

vacation tip #7: Go outside your past experiences and be wowed

by the ordinary

by the ordinary

I think we all have a

tendency to want to recreate past joys, so many of us go to the

same vacation spot over and over again. But I've found that

my second time with the same vacation often doesn't hold a candle

to the first. That's why I was so glad Mark recommended we

go to Pawleys Island instead of my family's traditional beach

haunt of Ocracoke.

Mom and I got excited

before we even approached the ocean. She had never been this far south

in her life, and I'd only seen a field of cotton once

before. "Look at the cotton!" Mom and I exclaimed as we

whizzed down the highway.

And while my favorite

event of our first vacation day was the instant we got to our

rental house and I walked out on the porch and saw the ocean for

the first time in years, Mom's fondest memory was stopping at a

gas station and walking over to a weedy margin to look at

wildflowers.

Which isn't to say there wasn't plenty of extraordinary on our

vacation too. But if you get a kick out of the common,

everything else is icing on the cake.

| This post is part of our Gratuitous Vacation Photos lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We had some trouble getting

the ATV started.

I took the battery to an auto

parts store for testing. They only measured 90 cranking amps when the

minimum for this size is 190.

The voltage was over 12

volts, which has fooled me in the past before I learned that engine

starting is all about cold cranking amps.

I've spent most of

this week with my brain in 2006, reading back over journals from

that era as research for my

upcoming ebook.

One thing that's struck me is how much rock we've thrown into our

driveway, and how little difference there seems to be between 2006

and today.

I'd say that our

driveway is moderately dry at the moment, but it still has lots of

water standing in the ruts...and lots of ruts. Part of the

problem is that we focus our efforts on those ruts, and we keep

changing vehicles so the orientation of the ruts keeps changing,

but I think part of the issue is also that we're looking at the

problem with the wrong perspective.