archives for 02/2013

The

Cows Are Out by

Trudy Chambers Price is a good farm memoir to read on a rainy

day. The author, her husband, and their two sons spent 23 years

on a moderate-sized dairy farm (25 to 75 Holsteins) in Maine. The

story itself is very engaging, aided by the frequent family photos and

the author's pleasant style, but as Mom told me when she lent me the

book, "It's the wrong kind of dairy farm!"

The

Cows Are Out by

Trudy Chambers Price is a good farm memoir to read on a rainy

day. The author, her husband, and their two sons spent 23 years

on a moderate-sized dairy farm (25 to 75 Holsteins) in Maine. The

story itself is very engaging, aided by the frequent family photos and

the author's pleasant style, but as Mom told me when she lent me the

book, "It's the wrong kind of dairy farm!"

Mom was coming fresh

from reading Folks,

This Ain't Normal,

so she was struck by the amount of time the Prices' cows spent in

confinement on concrete floors. From what I read, though, dairy

cows are a whole 'nother ball game, and it takes a lot of extremely

careful planning to raise them on pasture alone. The Prices did

have lots of grazing area they turned the cows into in the summer, and

I suspect stockpiled

winter grazing

hadn't hit the forefront during the sixties, seventies, and eighties,

so folks didn't have any other option than to feed their cows hay in

the barn all winter.

While I'm willing to

give the operation a pass on the confinement score, I do think it

should be read as a cautionary tale about debt. First the couple

went into debt to buy the farm, then they went further into debt to

purchase machinery (and yet more machinery as time wore on). Two

years after moving to the land, the author had to start teaching school

to pay the bills, and it was clear that even after 23 years, they had

yet to break even.

This cycle of debt is

par for the course in mainstream American farming today, but I think

it's also what drives the little guy out and turns our farmland over to

mammoth agribusinesses. In the Prices' shoes, I'd like to say

that Mark and I would have thought outside the box and dreamed up

value-added products so we could keep equipment purchases to a minimum

and make a living wage, but it's hard to think straight if you're up at

3:30 every morning to do the milking.

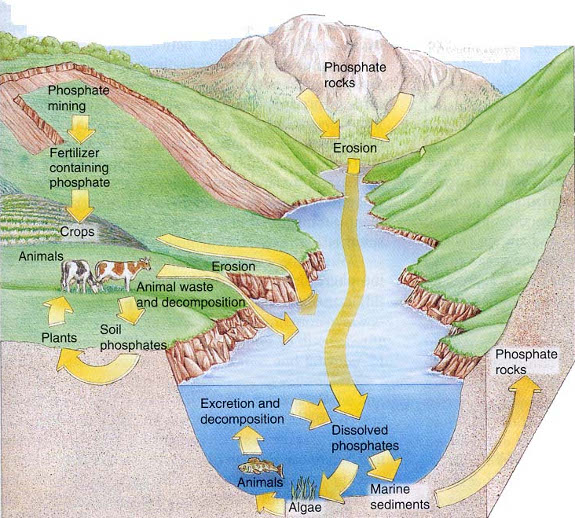

The last thorny soil

issue I want to cover is phosphorus. Steve

Solomon's worksheets

aim for an equal amount of phosphorus and potassium in the soil, while Michael

Phillips thinks more phosphorus is better and recommends building

orchard soil to have twice as much phosphorus as potassium. On

the other hand, Harvey

Ussery explained

that excessively high phosphorus levels cause a decline in mycorrhizal

fungi, which means that plants actually have a harder time finding enough

phosphorus and can experience a deficiency. In a worst case

scenario, extra phosphorus can even wash into streams and cause

eutrophication. Fertilizing with manure (especially chicken

manure) boosts phosophorus levels in the soil quickly, so the question

is --- should I be concerned about phosphorus excesses?

| Location | lbs P2O5/acre | Deficit or excess P |

| Powerline pasture | 56 | −237 |

| CP3 and CP4 | 225 | −209 |

| CP5 | 117 | −196 |

| Forest aisles | 269 | −127 |

| Blueberries | 345 | unsure |

| Front berries | 778 | −21 |

| Forest garden | 1136 | 180 |

| Back garden | 1599 | 354 |

| Front garden | 2029 | 487 |

| Mule garden | 2246 | 551 |

Using Solomon's

recommended phosphorus levels, it's clear that our native soil is low

on phosphorus, but that my preferred horse manure fertilizer has

increased levels within the vegetable garden beyond the recommended

range. Of course, if I was using Phillips' goal instead of

Solomon's, the vegetable garden would actually be considered deficient

in phosphorus like the rest of our homestead.

Solomon backs up

Phillips by writing that excess phosphorus is seldom a problem since it

will actually increase the nutrient density of your produce. In

fact, in a perfect world, Solomon believes our soil would have 2,000

to 5,000 pounds of phosphorus per acre, at which level enough of the

mineral would

naturally be released each year to feed our crops with no additional

applications of fertilizer. Based on these figures, I suspect we

can carry on with my heavy manuring for another five or so years before

phosphorus levels in our vegetable garden exceed biologically healthy

amounts.

On the other hand, my

readings suggest that excess phosphorus can be an issue in the blueberry

patch, where the

extra phosphorus can cause some of the same deficiency symptoms you'll

notice from high pH or high calcium levels. I doubt that we're

anywhere near that level yet, but it might be worth focusing on

building acidic, low phosphorus, low calcium compost for that patch for

the future. And, one of these days, I'll probably have to escape

my reliance on off-farm manure and bring our homestead into more of a

closed loop. Stay tuned for a lunchtime series based on How

to Grow More Vegetables on that very topic soon.

This

post is part of our The Intelligent

Gardener lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

We upgraded our drinking

water filter system today.

It comes into the house and

enters a sediment filter, and then goes to our new UV filter, which is

3 times bigger than the old one.

The attractive stainless

steel container is made in Italy by a company called Minox. We found it on Amazon for

170 dollars.

It's been nearly a month

since I last posted about our partially-completed

greywater wetland,

but I haven't been entirely idle. Whenever the water's low enough

to cross the creek without hip waders and I don't have anything more

pressing to carry in from the parking area, I've tossed a ten-foot

section of pipe over my shoulder during my morning walk. I guess

that means the floodplain has been easily passable 6 days out of the

last 28.

With all the pipe nearby

for channeling water from the trailer to the

wetland, I finally dug the last part of the trench. I'd left two

feet

of buffer area right where the current pipes discharge so that the

soggy mess didn't end up in the trench until I was ready for it, but

now I dug on through.

What I discovered

underneath our current drain

out back was a

fascinating system I didn't know existed. Two feet out from the

discharge spot, the clay turned grey --- clearly it had gleyed itself. Closer in, a

band of white...something...had built up right around the base of the

pipes but a few inches under the soil. And atop that white band

was an astonishing number of earthworms.

True, the drain out back

created a soggy mess in front of our back door, and a mild swampy smell

in certain seasons. But I'm impressed by the earth's ability to

take lemons and make lemonaide. Given how well my non-system

works, I have high hopes an actual greywater wetland will work even

better.

The spigot that came with the

new Minox container was nice, but it didn't have a

place to attach a hose.

A new brass spigot with

matching utility hose cost about 10 dollars and only took a few minutes

to install.

I've been thinking about

Roland's comment yesterday where he suggested using copper to take

advantage of its anti-bacterial effects. Anna and I talked about it for

a while and she has an interesting idea to try suspending a mesh bag

full of pennies near the middle of the container.

No self-respecting

groundhog would have been out in yesterday's below-freezing, snowy

weather, but a flock of ten cardinals and half a dozen song sparrows

dropped by the garden for an afternoon snack. We don't

purposefully feed the birds, but our homestead does seem to provide

quite a lot of food for the local wildlife. I'm going to assume

that these seed-eating birds were hunting down grass and plantain

seeds, lowering my weeding pressure for the year to come.

These new chest waders are a

bit harder to put on than my

old hip waders, but the

extra distance and warmth makes up for the small hassle.

The boot tread is better

suited for our conditions here compared to the felt bottom on the hip

waders.

I went with a neoprene

material from Pro Line for 180 dollars.

This has been our

tastiest winter yet, especially when you consider the vegetables we're

still eating fresh.

When the snow and freezes

allow access, we're harvesting as many greens as we can eat out of the quick

hoops, although the

lettuce is starting to fade. Arugula has turned out to be a

quality winter salad green, growing faster than the lettuce and holding

up to colder weather, plus the sweet, spicy leaves are delicious when

they make up about 10% of a salad. I'd say we planted just the

right amount of lettuce (three beds) and arugula (one bed), and

actually grew too much kale (six beds under cover and fifteen more beds

of kale and other greens uncovered). (In case you're keeping

track at home, I use "bed" to mean an area about 18 square feet in

size.)

When the snow and freezes

allow access, we're harvesting as many greens as we can eat out of the quick

hoops, although the

lettuce is starting to fade. Arugula has turned out to be a

quality winter salad green, growing faster than the lettuce and holding

up to colder weather, plus the sweet, spicy leaves are delicious when

they make up about 10% of a salad. I'd say we planted just the

right amount of lettuce (three beds) and arugula (one bed), and

actually grew too much kale (six beds under cover and fifteen more beds

of kale and other greens uncovered). (In case you're keeping

track at home, I use "bed" to mean an area about 18 square feet in

size.)

Brussels

sprouts have been a

major boon, especially because they're tall enough that I can harvest

the little heads through a deep snow. We didn't grow nearly

enough, with only one bed in full production and three beds finally

starting to bear from their shadier spot in the front garden.

Next year, we'll put more plants in the sun as this variety moves off

our experimental list and onto our list of mainstays.

That's

it for the crops we're still harvesting out of the garden, except for

bits of Egyptian onions, thyme, parsley, and celery. But our

other stores are also doing admirably. The queen has been carrots, which have held up

perfectly in the fridge

root cellar (where they returned after a

week on the kitchen floor

covered by a towel during the coldest spell in January). We've eaten

fresh carrots, carroty soups, given away bagsful, and still have plenty

to carry us through until the spring crop. If anything, we could

probably get away with planting a little less than six beds next year,

but we'll probably hold steady.

That's

it for the crops we're still harvesting out of the garden, except for

bits of Egyptian onions, thyme, parsley, and celery. But our

other stores are also doing admirably. The queen has been carrots, which have held up

perfectly in the fridge

root cellar (where they returned after a

week on the kitchen floor

covered by a towel during the coldest spell in January). We've eaten

fresh carrots, carroty soups, given away bagsful, and still have plenty

to carry us through until the spring crop. If anything, we could

probably get away with planting a little less than six beds next year,

but we'll probably hold steady.

We haven't eaten as many

butternuts as in previous years because we mostly consume them in

butternut pies, which depend on good eggs, and we've started eating

eggs for breakfast, so we're perennially short. The stems are

beginning to go a bit hollow and imperfect squashes are starting to

rot, so I'm roasting up the many we have remaining to go in the

freezer. I'd say we should grow many fewer butternuts next year,

but if we increase our egg supply, that might not be true, and chickens

adore the seeds.

We ate the last cabbage out

of the fridge root cellar last week, and it wasn't a pretty

sight. I suspect cabbages would like it just a hair warmer than

carrots, or perhaps they just don't have as much keeping power, because the last cabbage

split open and started to grow a new head from the crack. We'll

grow the same amount this year because I clearly haven't entirely got a

handle on the crop, but I suspect we may scale up at a later date.

We ate the last cabbage out

of the fridge root cellar last week, and it wasn't a pretty

sight. I suspect cabbages would like it just a hair warmer than

carrots, or perhaps they just don't have as much keeping power, because the last cabbage

split open and started to grow a new head from the crack. We'll

grow the same amount this year because I clearly haven't entirely got a

handle on the crop, but I suspect we may scale up at a later date.

Of course, we've still

got garlic and sprouting beans and white potatoes (the last of which we

hardly eat), though we're a bit low on sweet potatoes (due to this

recipe increasing

our consumption). And then there's the contents of the freezer,

which seem to be holding up very well despite us eating soup about once

a day. While I won't mind fresh asparagus at all once April rolls

around, I don't think we'll be craving it quite as hard as we have in

the past.

How

to Grow More Vegetables by John Jeavons was an

interesting read, but I suspect it won't be as helpful to many backyard

growers as other gardening guides might be, mostly because How

to Grow More Vegetables is one of those books that

tells the "one true way" to garden. Rather than explaining the

science behind his gardening choices so you can pick bits and pieces to

apply to your own environment, the author assumes you will want to

completely mimic his GROW BIOINTENSIVE method in your garden.

How

to Grow More Vegetables by John Jeavons was an

interesting read, but I suspect it won't be as helpful to many backyard

growers as other gardening guides might be, mostly because How

to Grow More Vegetables is one of those books that

tells the "one true way" to garden. Rather than explaining the

science behind his gardening choices so you can pick bits and pieces to

apply to your own environment, the author assumes you will want to

completely mimic his GROW BIOINTENSIVE method in your garden.

(Yes, the term GROW

BIOINTENSIVE is in all caps throughout the book. Yes, this did

drive me a little nutty. No, I won't be repeating the term in all

caps throughout this post and those that follow.)

John Jeavons' method is

one he and his group, Ecology Action, have been polishing on their

California farm since 1971, when they heard about Alan Chadwick's

biointensive gardening tehcnique and decided to give it a try.

Chadwick had, in turn, compiled his own methodology from two sources:

the French-intensive

methods that have inspired others like Eliot Coleman, and Rudolf Steiner's

biodynamic system from the 1920s.

I'll write more about

the Grow Biointensive method (which is the term Jeavons coined for his

own offshoot) in later posts in this lunchtime series, but for now,

it's worth understanding the purpose behind his methodology.

Unlike the average backyard gardener who is primarily interested in

cutting costs and/or feeding her family the most delicious and

nutritious food available, Jeavons' plan is to save the world.

His goal is to reduce the land area, water, and petroleum required to

grow food so that we can fit many more people on the earth without

starvation. As a result, you'll see a lot of focus on calories

per square foot and much less emphasis on taste and nutrition.

My final major peeve with

this book stems from the fact that biodynamic

practitioners and I have a different worldview. Jeavons doesn't write

about gnomes, but he does anthropomorphicize his plants ("Plants...do

like to have human companionship..."), and he includes information that

is dicey at best (such as his assertion that hummingbirds will hang

around to pollinate crops --- I can't think of any major vegetables

pollinated by hummingbirds). You'll find a chapter on planting by

the moon along with lots of unsupported companion-planting data, and

the scientific-minded reader will soon start to doubt the more relevant

parts of Jeavons' method due to their proximity to less scientific

assertions.

My final major peeve with

this book stems from the fact that biodynamic

practitioners and I have a different worldview. Jeavons doesn't write

about gnomes, but he does anthropomorphicize his plants ("Plants...do

like to have human companionship..."), and he includes information that

is dicey at best (such as his assertion that hummingbirds will hang

around to pollinate crops --- I can't think of any major vegetables

pollinated by hummingbirds). You'll find a chapter on planting by

the moon along with lots of unsupported companion-planting data, and

the scientific-minded reader will soon start to doubt the more relevant

parts of Jeavons' method due to their proximity to less scientific

assertions.

All of that said, the

book is worth a read with a critical eye if you're a serious gardener

and feel able to separate the wheat from the chaff. I'll include

a little of both in later posts this week.

| This post is part of our How to Grow More Vegetables lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

"Fold it up like a taco", was Bradley's advice on the best way to carry

in the red roofing tin last week.

To hold it in place tie a

rope around each end, which can double as a shoulder strap.

Image credit goes to our new

helper BJ.

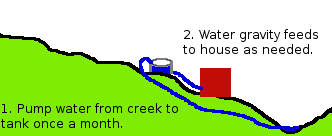

Mark's a big fan of

backups, and our dual water system is a good example of why his

methodology is perfect for the farm. As I've written previously,

we have two water systems --- one for potable (drinking) water and one

for nonpotable water.

The

nonpotable

water system involves pumping water from the creek to a 1,000

gallon tank. The creek drains a large watershed, so the water is

only moderately pure, meaning it's only good for washing and

irrigation. But there's a lot of it, and once we fill the tank,

water gravity-feeds to the house with no need for electricity for about

a month. That means during power outage situations, we still have

a lot of semi-pure water with little effort that we can use for washing

hands, dishes (with a bit of bleach), and clothes. On the

negative side, though, we haven't quite got this waterline to the point

where it doesn't freeze when lows drop into the mid-teens, although

water does start flowing again pretty quickly once temperatures rise

above freezing. So we spend what amounts to perhaps five full

days a year with the nonpotable water inaccessible due to cold weather.

The

nonpotable

water system involves pumping water from the creek to a 1,000

gallon tank. The creek drains a large watershed, so the water is

only moderately pure, meaning it's only good for washing and

irrigation. But there's a lot of it, and once we fill the tank,

water gravity-feeds to the house with no need for electricity for about

a month. That means during power outage situations, we still have

a lot of semi-pure water with little effort that we can use for washing

hands, dishes (with a bit of bleach), and clothes. On the

negative side, though, we haven't quite got this waterline to the point

where it doesn't freeze when lows drop into the mid-teens, although

water does start flowing again pretty quickly once temperatures rise

above freezing. So we spend what amounts to perhaps five full

days a year with the nonpotable water inaccessible due to cold weather.

Our

potable water supply is pumped up out of a shallow well (which looks

like a dark box in the photo at the top of this post), then is piped

through a sediment

filter and a UV light,

before ending up in the new,

larger reservoir

Mark recently installed in our kitchen. The main benefit of the

well is that we own its entire (small) watershed and the land is

completely wooded, so our well water is almost certainly free of

pesticides and herbicides. There's much less of the well water,

though, and it seems wasteful to run water through the UV light

(requiring electricity) and a sediment filter (that has to be changed

every few months) for uses other than washing and cooking. On the

other hand, the line never freezes, so as long as we have power, we

have water of some sort.

Our

potable water supply is pumped up out of a shallow well (which looks

like a dark box in the photo at the top of this post), then is piped

through a sediment

filter and a UV light,

before ending up in the new,

larger reservoir

Mark recently installed in our kitchen. The main benefit of the

well is that we own its entire (small) watershed and the land is

completely wooded, so our well water is almost certainly free of

pesticides and herbicides. There's much less of the well water,

though, and it seems wasteful to run water through the UV light

(requiring electricity) and a sediment filter (that has to be changed

every few months) for uses other than washing and cooking. On the

other hand, the line never freezes, so as long as we have power, we

have water of some sort.

Having two systems means

we probably spend twice as long fixing things that inevitably go wrong,

and it definitely cost more to set up than a single system would

have. But it's nice knowing that our water supply is completely

under our own control, and I suspect we end up paying less than

neighbors on city water even in a climate where water is

plentiful. There are several other options that could have worked

as well --- collecting rainwater off the roof, using different kinds of

filters --- but this system seems to suit our farm very well.

One

of our readers, Brian, sent me an email for help "or harsh reality"

about his troubled apple tree. He wrote:

One

of our readers, Brian, sent me an email for help "or harsh reality"

about his troubled apple tree. He wrote:

"The tree came from a place I wouldn't buy from again (directgardening.com) and it was a whip that had been topped and was bud grafted with supposedly 5 different varieties. It appears all the branches have the knots forming and I may just be growing a tree that is the rootstock.

"What do you think? Do you think I should just cut it down and try cleft grafting the trunk and start over?"

It's always tough to pull out

a fruit tree you paid good money for and babied for multiple years, and

I have to admit I know next to nothing about burr knot. Hopefully

one of you can help Brian out. What do you think --- does the

burr knot on the branches mean the whole tree is rootstock? Is it

a goner?

It's always tough to pull out

a fruit tree you paid good money for and babied for multiple years, and

I have to admit I know next to nothing about burr knot. Hopefully

one of you can help Brian out. What do you think --- does the

burr knot on the branches mean the whole tree is rootstock? Is it

a goner?

(This post is in place

of an update on Shannon's

rabbits since life

is still hectically busy down south. Shannon does report that

"The baby rabbits are eating voraciously," so hopefully he'll have more

information in a week kor two.)

This do it yourself workbench

went together in about an hour today.

It will function as our new

14 gauge wire cutting station for chicken waterers.

Total material cost is just

under 20 dollars.

I did the first round of

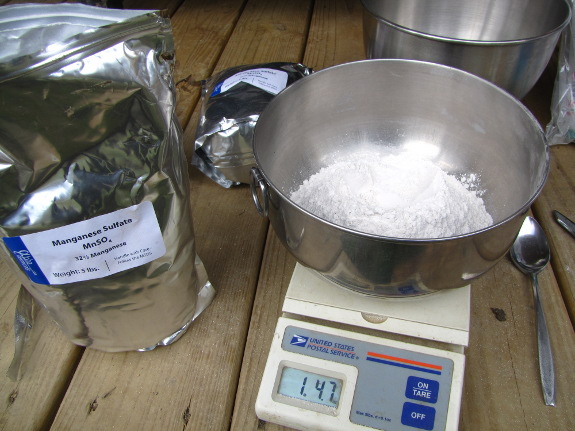

remineralization of our garden soil this week. If you haven't

been reading along, you can learn how I

figured out how much of each mineral I needed here and here, and I also recommend

checking out the book The

Intelligent Gardener

for more information on why we want to remineralize our soil.

After doing the math to

calculate amounts, the next step was to come up with the

minerals. I could have asked our feed store to order 50 pound

bags of each, saving about 50% per pound. But we only needed 10

or 15 pounds of several different minerals, and you have to keep

moisture out of some of the compounds during storage. In our wet

climate, I figured it made more sense to order smaller quantities

online, and Alpha

Chemicals seemed to

be the cheapest choice for most.

As a side note, I'm 95%

sure that even though 20 Mule Team Borax is marketed as a laundry

additive, the box contains pure borax. If my garden

starts sudsing up, I'll let you know....

I used a scale and some

mixing bowls to weigh out the quantities of the minerals I'm adding in

small amounts --- manganse sulfate, copper sulfate, zinc sulfate, and

borax. Even though my soil analysis called for salt, my

understanding of soil cations talked me into leaving the

salt out this year. Every part of our garden is getting gypsum to

flush out excess cations, and sodium is the cation that clings least

tenaciously to the soil particles. My understanding of the

chemistry says that if I add salt and gypsum at the same time, I'd be

flushing my salt right out of the dirt.

Solomon recommends

mixing all of the trace minerals together, then adding them to the

items you use in bulk (like gypsum and lime). I followed his lead

on my first garden area, but I won't in the future. Our gypsum

came from the feed store pelletized, and the other minerals are

powders, so the latter tend to sink to the bottom of the wheelbarrow no

matter how carefully you mix them together. Luckily, I spread

sparingly, making three passes over the garden, so each garden spot

probably got a relatively even helping of the trace minerals as well as

the gypsum. (There's no lime in this garden area, but I plan to

mix the lime and gypsum together for areas that use both.)

I crunched the numbers

to include spreading amendments on the aisles as well as on the

beds. I could have saved cash by only treating the latter, but I

figure some vegetables probably spread their roots out beyond the bed

boundaries, and we sometimes use grass clippings as mulch, so it's best

to remineralize everything.

Each garden zone gets

its individual prescription, and I've only treated the front garden so

far. I'll let you know how I change my technique as I hit the

other areas in turn. Meanwhile, I should tell you that we've

already spent $169 on the trace minerals, and we'll be spending at

least that much again on the gypsum and lime, so this isn't a cheap

proposition. If we can taste the results in the first year,

though, it'll be worth it.

One of Jeavons' goals in his

Grow Biointensive garden is to create a closed loop, growing all of his

compost on-farm. Finding enough compost can be an issue for

sustainable gardeners since you won't get nearly enough organic matter

from your garden "waste" to feed next year's plants. Jeavons

solves that problem by focusing a huge proportion of his growing area

on grains that not only produce a lot of calories, but also build

carbon for the compost pile.

One of Jeavons' goals in his

Grow Biointensive garden is to create a closed loop, growing all of his

compost on-farm. Finding enough compost can be an issue for

sustainable gardeners since you won't get nearly enough organic matter

from your garden "waste" to feed next year's plants. Jeavons

solves that problem by focusing a huge proportion of his growing area

on grains that not only produce a lot of calories, but also build

carbon for the compost pile.

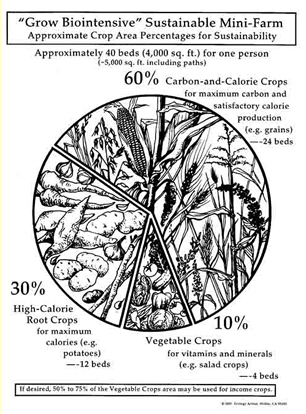

The diagram to the

right, from Ecology

Action's website,

shows how the group breaks their farm down into categories:

- 60% grains (wheat, rye, oats, barley, triticale, corn, sorghum,

amaranth, quinoa, pearl millet, and also non-grains such as fava beans,

sunflowers, filberts, and grapes)

- 30% roots (leeks, garlic, parsnips, sweet potatoes, salsify,

potatoes, Jerusalem artichokes)

- 10% vegetables (everything else, including lower-yielding roots like turnips and onions)

Looking at Jeavons

numbers, I'm a bit shocked by his ratios --- I'd be concerned if my

diet consisted nearly entirely of grains

and roots. Jeavons allots 4,000 square feet of growing area

(excluding

aisles) to totally feed each person, which means I'd have to grow all

of the non-root vegetables the two of us eat in 800 square feet --- a

bit

less space than we currently commit to tomatoes and leafy greens.

Meanwhile, I'd have to drastically expand the 21% of our garden (and

diet) we

commit to high-carbohydrate crops (roots and grains), and would

actually

increase our total vegetable growing area by 45% to match Jeavons'

numbers.

As with other parts of How

to Grow More Vegetables, I feel like Jeavons' garden

divisions are based more on ideology than on reality. Yes, the

concept of creating a closed-loop farm is intellectually interesting,

but why is it unsustainable to bring in manures if they're being heaped

up in a stack of "waste" by your neighbors? Alternatively, why

not add animals to your own farm --- many studies have shown that

small-scale, human-labor systems generally produce more calories per

acre if you include animals wisely in multi-layered systems than if you

stick to growing plants alone.

As with other parts of How

to Grow More Vegetables, I feel like Jeavons' garden

divisions are based more on ideology than on reality. Yes, the

concept of creating a closed-loop farm is intellectually interesting,

but why is it unsustainable to bring in manures if they're being heaped

up in a stack of "waste" by your neighbors? Alternatively, why

not add animals to your own farm --- many studies have shown that

small-scale, human-labor systems generally produce more calories per

acre if you include animals wisely in multi-layered systems than if you

stick to growing plants alone.

On the other hand,

Jeavons' system can be considered from another point of view as a way

of including cover crops that are useful for more than one

purpose. Rather than planning your grains to be winter-killed

or mow-killed, if

you've got the space to let them go to seed (and the equipment to

process the grain), you'll end up with even more organic matter plus a

high-calorie crop. In traditional farming systems from a century

or two ago, this is exactly what most farmers would do...but then

they'd feed most of those grains to the chickens, pigs, and milk cow to

produce high-quality protein for the family.

| This post is part of our How to Grow More Vegetables lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It takes a full hour to drain

a gallon of fuel from our Champion

generator.

Using an old rag to filter

the fuel will hopefully eliminate any particles that may have found

their way into the bucket during this operation.

Once the tank is empty I

start it up to burn off any remaining fuel.

I don't usually let

anyone help me with pruning, partly because I'm a control freak but

mostly because I'm still feeling my way along and don't feel

comfortable enough giving instruction. The raspberries

and blackberries are

pretty straightforward, though, and B.J. picked up my pruning method

astonishingly quickly Monday. (Yes, he is shaping up to be

indispensible. No, you can't have him.)

Last year, the brush

pile full of

pruned-off branches did okay in the middle of the forest garden, so I

decided to repeat the experiment. The previous pile had sunk down

to where it was only a few feet tall, so this year's prunings didn't

really raise the height up beyond the previous levels. Hopefully

my work eradicating weeds growing up through the pile last summer will

make the area semi-weed-free this year, and last year's cuttings should

be rotten enough by now that the nearby apple roots can take advantage

of the compost.

Here's the finished

product --- blackberries, red raspberries, black raspberries, and kiwis

are now all pruned. They look a bit like shorn sheep against the

snow, but I've found that heavy pruning is entirely worthwhile with

brambles. You get huge, delicious fruits that are easy to pick,

so you eat more of them.

Plus,

it's just fun out to be out in the garden in early February, watching

the daffodil leaves poke up through the snow and the song sparrows flit

about. Pruning week is one of my favorite times of the year, so

I'm glad I've still got all the fruit trees to go. Now, if I can

just learn to wear gloves so I don't have to bite thorns out of the

pads of my fingers all week....

Plus,

it's just fun out to be out in the garden in early February, watching

the daffodil leaves poke up through the snow and the song sparrows flit

about. Pruning week is one of my favorite times of the year, so

I'm glad I've still got all the fruit trees to go. Now, if I can

just learn to wear gloves so I don't have to bite thorns out of the

pads of my fingers all week....

The chapter in Grow

More Vegetables that

held up best to scientific scrutiny covered compost. Jeavons'

compost pile is very different from many I've seen because he

incorporates a lot of soil and keeps the C:N ratio quite high (44:1) as

a way of maximizing humus creation rather than minimizing cooking

time. This is where a lot of the grain

leaves and stems from his garden end up, along with kitchen waste,

twigs, and small branches, and the lignin in the woodier materials

tends to create more humus in the final product. While Grow

Biointensive piles take four months or more to fully cure, the organic

matter they produce also lasts much longer in the soil.

The chapter in Grow

More Vegetables that

held up best to scientific scrutiny covered compost. Jeavons'

compost pile is very different from many I've seen because he

incorporates a lot of soil and keeps the C:N ratio quite high (44:1) as

a way of maximizing humus creation rather than minimizing cooking

time. This is where a lot of the grain

leaves and stems from his garden end up, along with kitchen waste,

twigs, and small branches, and the lignin in the woodier materials

tends to create more humus in the final product. While Grow

Biointensive piles take four months or more to fully cure, the organic

matter they produce also lasts much longer in the soil.

Intriguing, but less

scientifically supported, compost facts in Jeavon's book include a

qualitative analysis of compost types. He asserts that compost

made from plants is four times better than that made from manure, and

that roots rotting directly in the soil are twice as good as plant

compost. With no extra information or citation, I'm left guessing

that maybe Jeavons means plant roots rotting directly into the soil are

most likely to turn directly into humus, but I'd be curious to hear

from anyone with more information.

| This post is part of our How to Grow More Vegetables lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Thank you BSmith for

commenting the other day about my lack of bracing on the DIY

work bench.

It had a slight wobble, but

two 2x4's on the bottom firmed it up and provided a place to install a

heavy duty shelf.

I also put an L bracket on

one of the rear legs to secure it to the deck.

We're zipping right through

the easy section of our emergency

preparedness goals,

with this week's addition being smoke and carbon monoxide

detectors. Even though I put it on the easy list, though, I soon

discovered that choosing a smoke detector is quite complex.

We're zipping right through

the easy section of our emergency

preparedness goals,

with this week's addition being smoke and carbon monoxide

detectors. Even though I put it on the easy list, though, I soon

discovered that choosing a smoke detector is quite complex.

You have to select either a model that relies on ionization to detect

open flames, or on a photoelectric sensor to notice smoldering

fires. Although there are some detectors that lead you to believe

they do both plus monitor for carbon monoxide, once you read the fine

print, none do.

In the end, we chose to

pay a bit more to cover all of our bases, getting a First

Alert SA320CN smoke detector (photoelectric and ionization) and a First

Alert CO400 carbon monoxide detector for the outside of each

sleeping area. Although the versions that hook into your

electrical systems do avoid the problem of forgetting to change

batteries, we opted for battery-powered models since power-outage

situations are when we have more open flames around and need smoke

detectors the most.

I would tell you about how

and where to install detectors in this post, but each device we bought

came with a huge, fine-print-filled instruction sheet that was

approximately the size of our kitchen table. So as long as you

take the time to read the instructions that come with your detector,

you'll know far more than you ever thought you needed to know about

installation and maintenance.

I would tell you about how

and where to install detectors in this post, but each device we bought

came with a huge, fine-print-filled instruction sheet that was

approximately the size of our kitchen table. So as long as you

take the time to read the instructions that come with your detector,

you'll know far more than you ever thought you needed to know about

installation and maintenance.

Other aspects of

Jeavons' Grow Biointensive system are less unique. Grow

More Vegetables sums

up the method with seven techniques:

- Double-digging

- Compost use

- Close plant spacing

- Companion planting

- 60-30-10 proportions of carbon-efficient, calorie-efficient, and other crops

- Open-pollinated seeds

- Interrelated farm system

Of the techniques I haven't

discussed in earlier posts, the one I'm most on the fence about is

double-digging (which is followed by loosening up the soil between

crops with broad forks, aka U-bars). Our oldest garden plot is

ready to go into its seventh growing season since the ground was last

dug into, and the plants there seem to do better every year, so I can't

say that loosening the soil is really essential. On the other

hand, I'm very careful to keep foot traffic on the aisles, and I can

see from Grow

More Vegetables

that Grow Biontensive's wider beds are often impacted by human traffic

--- for example, the author actually pictures a board you're supposed

to sit or stand on atop the bed while loosening the soil or

planting. If you regularly put human weight on your garden soil,

you probably do need to fluff it up from time to time.

Of the techniques I haven't

discussed in earlier posts, the one I'm most on the fence about is

double-digging (which is followed by loosening up the soil between

crops with broad forks, aka U-bars). Our oldest garden plot is

ready to go into its seventh growing season since the ground was last

dug into, and the plants there seem to do better every year, so I can't

say that loosening the soil is really essential. On the other

hand, I'm very careful to keep foot traffic on the aisles, and I can

see from Grow

More Vegetables

that Grow Biontensive's wider beds are often impacted by human traffic

--- for example, the author actually pictures a board you're supposed

to sit or stand on atop the bed while loosening the soil or

planting. If you regularly put human weight on your garden soil,

you probably do need to fluff it up from time to time.

Companion planting is

another dicey topic, and one I don't really feel expert enough to delve

into in depth. I used to lap up information on companion

planting, but my limited trials have shown no improvement when mixing

multiple types of vegetables together in the same bed. Meanwhile,

companion planting seems to always make the vegetables harder to

harvest and has lowered yields in my garden. Until I see some

side-by-side scientific studies proving that specific types of

companion planting work, I'll stick to my diverse garden with each

variety segregated in its own little bed.

I know I've been pretty

critical of a book that many seem to find ground-breaking, so I thought

I'd offer the same exposure to the other side of the argument.

After a similar series about square

foot gardening, a

reader sent me a lot of photos and an explanation of why the method

worked for him.

If there's a Grow Biointensive fan out there who wants to share their

side of the story, just email

me and I'll set the

record straight.

| This post is part of our How to Grow More Vegetables lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It took some wrangling, but

we managed to get the swamp bridge back in place.

We added a few more cinder

block supports which firmed it up nicely.

The next step will be to

anchor it down before the next flood.

For

round two of my remineralization campaign, I decided to take

Roland's advice and at least prevent skin contact with the

copper. Our first idea was to use a seed spreader, but the

mineral powders didn't seem to want to flow out, so I moved on to plan

B --- wearing gloves.

For

round two of my remineralization campaign, I decided to take

Roland's advice and at least prevent skin contact with the

copper. Our first idea was to use a seed spreader, but the

mineral powders didn't seem to want to flow out, so I moved on to plan

B --- wearing gloves.

We still have to buy

more gypsum and lime, but the trace minerals are all in place. I

skipped the blueberries because I couldn't decide

what to do there, and I skipped chicken pastures 1 and 2 because I

didn't test the soil in those areas.

The only other area I

left out was the three rows in the mule garden currently covered by

quick hoops. We're still eating greens and lettuce out of there

daily, and I don't want to risk imbibing a lot of metals

accidentally. I figure the quick-hoop-covered beds can also be my

control. If I see a huge problem everywhere else but none there,

I'll know the minerals are at fault.

1. Re-attach 2 pieces at the

center of the swamp

bridge.

2. Pound in metal fence posts

on all 4 corners.

3. Secure each post to the

side with an exterior screw.

The next flood will be the

real test to see if all this prevents it from floating away.

My father commented to ask

what's the difference between remineralization

and using chemical fertilizers. The answer is --- not much in the

short term, but hopefully a lot in the long term.

My father commented to ask

what's the difference between remineralization

and using chemical fertilizers. The answer is --- not much in the

short term, but hopefully a lot in the long term.

Most (perhaps all?) of

the minerals I've been applying are approved for

organic gardening because they're mined rocks, but they're really just

chemicals. I

don't believe that just because something's "natural" that it's safe

for my soil, and I don't kid myself by thinking that there may not be

some short-term damage to my soil microorganisms resulting from this

winter's application. I'm hopeful that by spring, though,

everything will have evened out.

That's the short-term

picture, but what about the long term? The purpose of

remineralization is to correct imbalances

in the soil that develop over millenia of rainfall and leaching. The theory is that if

you boost levels of trace minerals that have been washed out of the

earth, you can bring your soil back into balance and not have to repeat

the endeavor. (That said, it may take a few years of soil tests

and remineralization to return to the optimal levels, especially since

Solomon places application limits on several of the minerals, like

borax.)

In contrast, the chemical

fertilizers used in mainstream farming are generally meant to be

applied before every crop, and tend to create a cycle of dependency in

the soil. For example, if you use chemical nitrogen fertilizers,

the microorganisms in your soil that usually cycle nitrogen and make it

available to plants perish, so you have to keep applying chemical

nitrogen fertilizers. If remineralization works correctly, it

does the opposite --- you add minerals that microorganisms will keep

cycling in your garden indefinitely.

In contrast, the chemical

fertilizers used in mainstream farming are generally meant to be

applied before every crop, and tend to create a cycle of dependency in

the soil. For example, if you use chemical nitrogen fertilizers,

the microorganisms in your soil that usually cycle nitrogen and make it

available to plants perish, so you have to keep applying chemical

nitrogen fertilizers. If remineralization works correctly, it

does the opposite --- you add minerals that microorganisms will keep

cycling in your garden indefinitely.

Whether the theory will

stand up to reality is up for debate. I feel there's a 10% chance

I'll regret spreading all these chemicals on the soil, a large chance I

won't see any difference, and perhaps a 20% chance my strawberries will

taste astonishingly rich this year. Only time will tell.

(And, yes, it's all about the strawberries.)

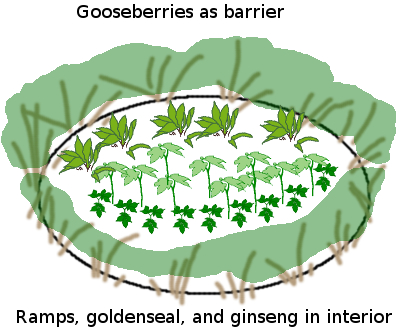

This is ginseng. What I like to

call, Appalachian Gold. I started hunting for the herb two years ago.

It was very hard to find at first, but after about a month or so I

could spot it very easily. Ginseng, in my personal opinion, is the most

beautiful plant in the forest.

This is ginseng. What I like to

call, Appalachian Gold. I started hunting for the herb two years ago.

It was very hard to find at first, but after about a month or so I

could spot it very easily. Ginseng, in my personal opinion, is the most

beautiful plant in the forest.

'Seng starts off the season

with bright green leaves and red berries in the center. Toward the end

of the season, the leaves turn to a vibrant yellow and the berries have

usually fallen off. A young plant has one or two prongs (branches) and

an older plant has three or four prongs. The photo above is about

mid-season. You can actually see the color change. Very beautiful!

It was my dad, who introduced me

to the herb. He, being a master ginseng hunter, has taught me a lot

about the herb and its medicinal properties. Have a headache? Simply

add about a teaspoon of dry, ground ginseng to some green tea. After

brewing is complete, use honey and a dash of cinnamon for sweetening,

and you have a natural energy drink that can knock a headache clean out

of your head.

It was my dad, who introduced me

to the herb. He, being a master ginseng hunter, has taught me a lot

about the herb and its medicinal properties. Have a headache? Simply

add about a teaspoon of dry, ground ginseng to some green tea. After

brewing is complete, use honey and a dash of cinnamon for sweetening,

and you have a natural energy drink that can knock a headache clean out

of your head.

I have yet to learn

everything about the herb, but I will keep you posted. Feel free to let

me know anything you may know about ginseng or any other plants and

herbs. I am always wanting to learn new things about plants and herbs.

Scraps of 2x4's spaced a

couple of inches apart is all it takes to store hip and chest waders in

a proper vertical fashion to prevent creasing.

I've played

around with taking advantage of willows' natural rooting hormones in the past, but have never

gotten very serious about it. However, an actual tested recipe in

The

Reference Manual of Woody Plant Propagation (combined with some gifted

fig cuttings) prompted me to give it another try.

I've played

around with taking advantage of willows' natural rooting hormones in the past, but have never

gotten very serious about it. However, an actual tested recipe in

The

Reference Manual of Woody Plant Propagation (combined with some gifted

fig cuttings) prompted me to give it another try.

To make rooting hormone

tea from first-year willow twigs, just strip off leaves (if any are

present), cut the wood into small pieces, and cover them up with

water. After 24 hours of steeping, pour off the liquid and use it

immediately, or store it in your fridge for up to six years.

Since willow rooting

hormone isn't as strong as commercial preparations, it's best to let

the base of your cuttings sit in the willow juice for a day before

moving them to their rooting chamber. I'm treating half my fig

cuttings with willow rooting hormone and letting half sit in water for

a day as a control and will let you know if I see a difference in

rooting.

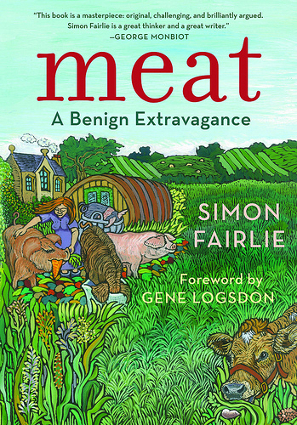

Meat:

A Benign Extravagance

by Simon Fairlie is an excellent book that I recommend to anyone who

cares about the environmental impact of your food, whether you're a

vegan, a fan of pastured meat, or are somewhere in between. While

the book doesn't touch on health issues or whether the actual act of

slaughtering animals is ethical, the author does an admirable job of

poring over the literature, crunching the numbers, and figuring out

whether

we're kidding ourselves when we think we can raise meat in a way that

heals the earth.

Meat:

A Benign Extravagance

by Simon Fairlie is an excellent book that I recommend to anyone who

cares about the environmental impact of your food, whether you're a

vegan, a fan of pastured meat, or are somewhere in between. While

the book doesn't touch on health issues or whether the actual act of

slaughtering animals is ethical, the author does an admirable job of

poring over the literature, crunching the numbers, and figuring out

whether

we're kidding ourselves when we think we can raise meat in a way that

heals the earth.

My favorite part of Meat is that Fairlie gives both

sides of the aisle fair consideration. He admits up front that

he's not a fan of CAFOs from an ethical perspective, and that he spent

several years as a vegetarian before beginning to raise his own dairy

goats and to eat the male kids. But he sets his own biases aside

and bashes all of the infomercials in which authors twist the numbers

to suit their ideology, whether the texts are written by vegans or by

industrial agribusinesses.

I put off reading Meat for several months because

the inside doesn't look inviting. There are a lot of footnotes,

no pictures, the text is a bit small, and it just looks like a tough,

academic read. Luckily, the author is engaging, and if you ignore

the footnotes, the text isn't nearly as dense as it first

appears. Instead, you'll likely have the most trouble translating

from British English to American English, and even that's not so

hard. (Just remember that soya is soybeans, ground nuts are

peanuts, and lucerne is alfalfa.)

This week's lunchtime

series will sum up the highlights of Simon Fairlie's book, but this is

one that I highly recommend you hunt down and read for yourself.

As usual, I'm looking at the author's information with an eye toward

tweaking our own permaculture setup, not to changing society, so I've

left out huge portions of Fairlie's argument that will be relevant to

those of you who depend more on the grocery store. If you're

interested in the bigger picture, it's worth putting in the time to

read Meat yourself.

| This post is part of our Meat lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

This walnut tree functioned

as a fence post for about 6 years.

It was in line with other

fence posts, so we just trimmed off the lower limbs and attached the

fence.

I might think twice about

taking a short cut like this in the future and use a treated 4x4 or

maybe even a 2x4 which would most likely last decades.

My favorite stump-dirt tree has been good to us

this year. I've already used about six gallons of beetle

castings, and B.J.

and I easily brought home another seven gallons or so Monday

afternoon. I figure there are even a couple more bucketsful left

for later seed starting, and of course the tree will fill back up over

the summer, fall, and winter and give us the same again next year.

If I look like I'm

praying to the tree, I kinda am. Who wouldn't be grateful for

such perfect humus? This individual tree makes the best potting

soil I've ever used --- just the right levels of nutrients and

water-holding capacity. Stump dirt from box-elders isn't even in

the same ball park, and tulip-trees and apples are head and shoulders

below this beautiful old beech.

The best stump dirt is

really little balls of beetle poop, and nearly everything spilling out

of this tree fits the bill.

More on what I used my

stump dirt for in a later post.

I've written previously about

the

argument that eating meat is bad for the environment because it's an

inefficient use of land. The figure most

people bring up is that it takes 10 times as much land area to produce

meat as to produce grain. My gut feeling is that the figure

seemed too simplistic, so I was very glad to see someone willing to put

more time into crunching the numbers and thinking the issue through.

I've written previously about

the

argument that eating meat is bad for the environment because it's an

inefficient use of land. The figure most

people bring up is that it takes 10 times as much land area to produce

meat as to produce grain. My gut feeling is that the figure

seemed too simplistic, so I was very glad to see someone willing to put

more time into crunching the numbers and thinking the issue through.

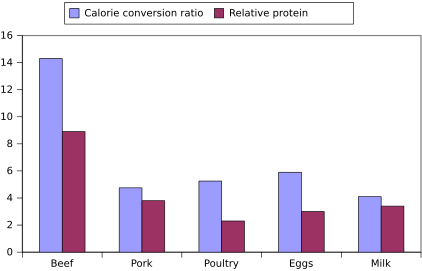

Simon

Fairlie began with

the basics --- feed

conversion ratio

for a few types of factory-farmed livestock. Next, he went a step

further and considered the protein conversion ratio, factoring in the

figure (agreed on by both pro- and anti-livestock folks) that animal

protein is 40% more valuable nutritionally than plant protein.

The results are  shown in the graph at the top

of this post, with beef being very inefficient (14.3:1 energetically

and 8.9:1 in terms of protein) and poultry being relatively efficient,

especially when it comes to protein (2.3:1). Personally, I feel

that the protein conversion rate is the most important since that's

usually the sticking point when trying to feed yourself from a small

tract of land.

shown in the graph at the top

of this post, with beef being very inefficient (14.3:1 energetically

and 8.9:1 in terms of protein) and poultry being relatively efficient,

especially when it comes to protein (2.3:1). Personally, I feel

that the protein conversion rate is the most important since that's

usually the sticking point when trying to feed yourself from a small

tract of land.

As I'll explain later

posts, there are other mitigating factors that change the feed

conversion ratios mentioned above, but this is a good starting point

for an unbiased consideration of the value of meat, especially if you

just buy your food from the grocery store. The conclusion Fairlie

comes too is that meat is a luxury product...but so are most fruits,

vegetables, and oils. For example, soybean oil actually requires

more arable land to produce than pastured dairy, and pigs can often

make fats more efficiently than soybeans as well. If you belive

that it's unethical to use more land producing your food than is

absolutely necessary, you should probably follow

the lead of the Grow Biointensive method and get nearly all of your

food from grains.

| This post is part of our Meat lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

When the walnut

tree fence post fell it

took out another one close by.

It pushed back in place, but

needed some help staying up.

I've seen the Power Company

shore up a pole this way, and with any luck the 14 gauge galvanized

wire will hold it in place for many years in the future.

Valentine's Day week is

when we often achieve the first rumblings of spring lift-off here on

the farm. Sure enough, taking the cover off the newly-seeded

lettuce quick hoop

just before a big rain resulted in sprouts the next day.

Meanwhile, my three

flats of onion seeds are starting to come up, so I've moved them to the

porch to capture sunlight on pretty days. Yes, this year I'm

going to be one of those overambitious gardeners who carries flats in

and out since she doesn't have enough growing space indoors.

Luckily, onion seedlings can take a light freeze, so they won't be too

much bother.

Finally, there are the eggs

waiting to go in the incubator Thursday or Friday. I

was going to start my first round of chicks a little later this year,

but Sarah's letting me get in on her chick order to add some good

laying genetics to our flock, and I want my chicks to hatch when hers

arrive.

Finally, there are the eggs

waiting to go in the incubator Thursday or Friday. I

was going to start my first round of chicks a little later this year,

but Sarah's letting me get in on her chick order to add some good

laying genetics to our flock, and I want my chicks to hatch when hers

arrive.

Any signs of spring in

your garden?

The

efficiency figures in my last post for raising various types of

meat make some big assumptions that aren't even true in cultures like

ours where most livestock are raised in factory farms, and are even

less true in other parts of the world. For example, the

astonishingly inefficient beef figures are mitigated by the fact that

most cattle, even in the U.S., are raised on pasture with little or no

grain during their youth, and are only moved to feedlots to be fattened

before slaughter. Next, consider that the hides of cows are used

for leather, collagen from connective tissue is used to make glue,

gelatin is eaten and used in plastic, and fats are used in soaps and

other applications. Factoring in these two new bits of data,

Fairlie further crunches the numbers to lower the feed conversion ratio

of beef in industrial societies to around 7:1 or 8:1.

The

efficiency figures in my last post for raising various types of

meat make some big assumptions that aren't even true in cultures like

ours where most livestock are raised in factory farms, and are even

less true in other parts of the world. For example, the

astonishingly inefficient beef figures are mitigated by the fact that

most cattle, even in the U.S., are raised on pasture with little or no

grain during their youth, and are only moved to feedlots to be fattened

before slaughter. Next, consider that the hides of cows are used

for leather, collagen from connective tissue is used to make glue,

gelatin is eaten and used in plastic, and fats are used in soaps and

other applications. Factoring in these two new bits of data,

Fairlie further crunches the numbers to lower the feed conversion ratio

of beef in industrial societies to around 7:1 or 8:1.

Pigs and chickens

produce fewer useful side products and don't get as much out of grass,

so their feed conversion ratios stand firm if you stick to industrial

conditions. However, if we went back in time even twenty years,

before it became illegal to feed wasted human food to livestock, pigs

especially would become much more efficient converters of grain to

meat. Fairlie suggests that if we simply used the food thrown

away by Americans every day, swill would supply 9% of the diet of the

pigs in our current factory farms, and that doesn't factor in other

historical feeds such as whey, spoiled produce on farms, and

slaughterhouse wastes. In poorer countries that haven't

implemented anti-swill-feeding  laws, pigs are often fed only

1.76 pounds of grain for every pound of meat produced, which would be

an astonishing feed conversion rate of 1.1:1 calorically, if my math is

right. (I'm guessing 1385 calories per

pound of pork and 898 calories per pound of grain.)

laws, pigs are often fed only

1.76 pounds of grain for every pound of meat produced, which would be

an astonishing feed conversion rate of 1.1:1 calorically, if my math is

right. (I'm guessing 1385 calories per

pound of pork and 898 calories per pound of grain.)

While swill is most

important when making chickens and pigs more efficient, ruminants like

cows and sheep pull their weight in areas with lots of non-arable

ground. For example, most of our farm couldn't be plowed without

producing extreme erosion, but if I were willing to cut down trees, we

could rotationally graze ruminants on our entire acreage and get food

from "unusable" land. In the UK, dairy cattle were historically

raised in spots like this, getting half their protein from grass and

half from grain, with a protein conversion rate for the milk of

1.5:1. Considering that animal protein is thought to be 1.4 times

as nutritionally beneficial as plant protein, that sounds like a very

efficient use of grain!

| This post is part of our Meat lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I first wanted the more heavy

duty fence posts to anchor the swamp

bridge, but realized we

used them all up on the high

density orchard experiment.

Turns out the thinner and

cheaper metal fence post was a better fit for this application.

The flat side snugged up

nicely with the swamp bridge and the pre-drilled holes made securing it

easy.

I felt much better about my

two previous fig-rooting failures when the experts explained that rooting

anything is dependent on a dozen different conditions, so you can think

you're doing the same thing and get completely different results from

different batches. Nevertheless, I'm also pretty sure I did

several things wrong in my previous fig-rooting experiments, so I'm

hopeful I'll see success in round three.

I felt much better about my

two previous fig-rooting failures when the experts explained that rooting

anything is dependent on a dozen different conditions, so you can think

you're doing the same thing and get completely different results from

different batches. Nevertheless, I'm also pretty sure I did

several things wrong in my previous fig-rooting experiments, so I'm

hopeful I'll see success in round three.

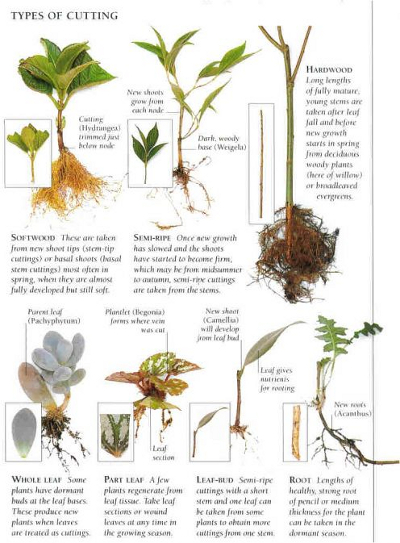

First of all, I didn't

use rooting hormones previously, and figs are supposed to be one of the

plants that do well with the chemical nudge. While it would be

easy to buy the exact rooting hormone recommended for figs (1,000 ppm

IBA in a 5 second dip), I wanted to test out my willow

rooting hormone.

So I soaked half my figs in water and half in willow tea the day before

potting them up.

I'm pretty sure my stump

dirt is just fine as

a rooting medium, so I'm repeating that part of  the procedure. However,

I think I was actually keeping things too damp and hot previously, thus

the overwhelming

fungal growth.

the procedure. However,

I think I was actually keeping things too damp and hot previously, thus

the overwhelming

fungal growth.

The step where someone

recommended wrapping

the cuttings in wet newspapers and sealing them inside a ziplock bag

also appears to have flaws. My new understanding is that this

procedure was meant to callous the cut tissue, but that would have

happened better without the damp paper towels. Rather than

modifying it, I decided to completely skip the callousing step this

time around.

I'm also opting to leave

off the humidity dome (aka plastic bag) I'd previously put over top of

my pots. While necessary for softwood cuttings (if you don't have

a misting setup), holding in too much moisture can actually be a bad

idea with hardwood cuttings.

So fig rooting

experiment 3 is going to be ultra simple. I snipped the terminal

buds off any cuttings that had them, cut the bottoms of all the

cuttings to expose fresh tissue (since they'd been sent through the

mail), and pushed them most of the way into a pot of stump dirt.

I put four pots partially on a heating pad on low, and will water them

if the soil seems to be drying up.

I now know that an

absence of leaves is good news early on. You want the cuttings to

be putting all of their energy into root growth, so I won't worry if

the twigs don't leaf out for several weeks. That's also why too

much heat is a bad thing --- it can tempt the plants to use up fleeting

carbohydrates above ground before they have enough roots to become

active. Our house is pretty cool in the winter, though, so I

figure a heating pad on low will help rather than hurt.

Now it's just a matter

of waiting and hoping. Maybe three will be the charm? (By

the way, Brian also gave me a few Hinnonomuki Red Gooseberry cuttings,

which I'm treating the same way. Thanks so much for the excellent

scionwood, Brian!)

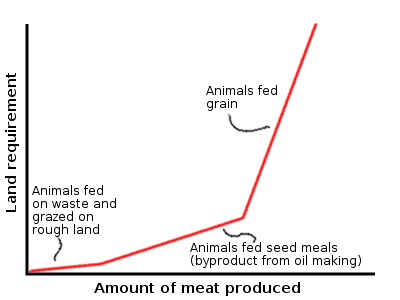

What I've been leading up to

with my previous two posts is Fairlie's distinction between what he

calls "default livestock" and luxury animals. By Fairlie's

definition, default livestock are the animals we could raise primarily

on byproducts, food waste, or uncultivable land, with seed meal being a

halfway house --- it is a byproduct, but is also valuable by

itself. The chart above shows that if we stuck to default

animals, especially if we exempt seed-meal-fed animals from our

calculations, we'd be using barely any land at all to produce our meat

and dairy products. Although Fairlie doesn't come right out and

say it, I'll go out on a limb and say that at the default animal level,

it's more efficient to eat meat than not. Beyond that, meat is an

inefficient use of land.

What I've been leading up to

with my previous two posts is Fairlie's distinction between what he

calls "default livestock" and luxury animals. By Fairlie's

definition, default livestock are the animals we could raise primarily

on byproducts, food waste, or uncultivable land, with seed meal being a

halfway house --- it is a byproduct, but is also valuable by

itself. The chart above shows that if we stuck to default

animals, especially if we exempt seed-meal-fed animals from our

calculations, we'd be using barely any land at all to produce our meat

and dairy products. Although Fairlie doesn't come right out and

say it, I'll go out on a limb and say that at the default animal level,

it's more efficient to eat meat than not. Beyond that, meat is an

inefficient use of land.

So what would your diet look

like if you only ate default livestock? Each person would get

about 40 pounds of meat per year plus about 86 pounds of milk (or 8.6

pounds of cheese). I don't keep track of how much dairy we buy,

but I figure Mark and I currently eat about 100 pounds of meat per year

apiece, over twice the default figure but less than the American

average of 166 pounds per year. Of our meat, the 76 pounds of

lamb and deer could probably count as default livestock since both

graze on non-arable land, but the 60 pounds of chicken meat is

grain-fed, as is the storebought bacon and ham we use to round out our

diet.

So what would your diet look

like if you only ate default livestock? Each person would get

about 40 pounds of meat per year plus about 86 pounds of milk (or 8.6

pounds of cheese). I don't keep track of how much dairy we buy,

but I figure Mark and I currently eat about 100 pounds of meat per year

apiece, over twice the default figure but less than the American

average of 166 pounds per year. Of our meat, the 76 pounds of

lamb and deer could probably count as default livestock since both

graze on non-arable land, but the 60 pounds of chicken meat is

grain-fed, as is the storebought bacon and ham we use to round out our

diet.

Of course, this is only

math until you start considering what default animals would really look

like on your homestead. Stay tuned for more tomorrow.

| This post is part of our Meat lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I went with a medium sized

cedar post we had laying around for today's chicken pasture gate

frame rebuild.

We decided to go with a

bigger width for times when we need to push a wheel barrow through.

I decided to do things a

little differently with our first bed of peas this year. Rather

than just soaking

the seeds to get

them off to a quick start, I put them in the sprouter and sprinkled  them with water several times

a day until the tiny roots began to push out of the seeds.

them with water several times

a day until the tiny roots began to push out of the seeds.

I also opted to plant

this early bed under the quick hoops, pulling out some declining

lettuce to make room. We'll know in a few months if these slight

alterations to our usual pea-planting method produce earlier edible-pod

peas.

For me, the most interesting part

of Fairlie's

book is his

suggestions for integrating livestock into permaculture systems.

The idea is that if your animals have jobs other than just meat

production, they are no longer an inefficient use of land.

For me, the most interesting part

of Fairlie's

book is his

suggestions for integrating livestock into permaculture systems.

The idea is that if your animals have jobs other than just meat

production, they are no longer an inefficient use of land.

The most obvious

non-edible use of livestock is collecting the animals' manure to

fertilize the garden. However, Fairlie points out that even

there, fertilizing your garden with animal manure is about 10% to 43%

less land-efficient per calorie than setting aside a third of the

growing area to produce legume and grain compost crops. (The

different percentages depend on what type of animal you're raising to

make the manure, and both factor in the value of the meat and/or dairy

produced by the animals as well as by the crops.)

While you lose some

land-efficiency by depending on animals to concentrate organic matter

and nitrogen, traditional societies have long known that livestock are

worth the effort in varied landscapes. Grazers

on non-arable land will eat up nitrogen (atmospherically deposited or

fixed by legumes) and bring it home when they come to the stable at

night, then their manure can be used to fertilize the main growing

area. In other words, animals are acting as self-powered

nitrogen-accumulators, a bit like you might plant dynamic

accumulators in the

garden to bring up minerals from the subsoil that your garden plants

can't usually reach.

Meanwhile, livestock can

be a good buffer against famine, especially in the absence of

refrigeration. You can fatten a pig during a time of plenty, then

kill it and eat the meat when the days get short and not much is

growing. On a larger scale, Fairlie considers eating meat to be a

buffer against large-scale problems --- if we're used to the

inefficiency of feeding grains to pigs and eating the pigs, when times

get tough, we can just eat the grains and have a bit of wiggle room to

change what we're doing before we really go hungry.

In general, though, the biggest bonus of

animals if you're trying to save energy is that they move by

themselves. If we used our livestock to transport people and

heavy objects, to mow between orchard trees, to clear new land, to turn

compost, and to control insects in our gardens, they would probably

look a lot more efficient than they do now. On the other hand, as

enticing as it is to consider returning to a previous era when a rugged

dairy cow might be expected to give milk and also to haul our supplies

through the mud from the parking area, energy is just so cheap at the

moment that mechanized transportation seems to make more sense.

In general, though, the biggest bonus of

animals if you're trying to save energy is that they move by

themselves. If we used our livestock to transport people and

heavy objects, to mow between orchard trees, to clear new land, to turn

compost, and to control insects in our gardens, they would probably

look a lot more efficient than they do now. On the other hand, as

enticing as it is to consider returning to a previous era when a rugged

dairy cow might be expected to give milk and also to haul our supplies

through the mud from the parking area, energy is just so cheap at the

moment that mechanized transportation seems to make more sense.

Perhaps the real lesson

homesteaders should take away from Fairlie's book is that we need to

ensure we're using the right default

livestock before

branching out. Are all of your food scraps being consumed by an

animal? If not, try adding a few chickens or a pig. Do you

have a lot of rough land and an absence of fertility in your

garden? Maybe you need to graze ruminants and fold them in a barn

or fallow field at night to get that manure.

Rather than planning

ahead for an apocalyptic vision where we don't have enough land to feed

our population, I think it's more useful to make changes in our lives

now to increase sustainability and also bliss. How would you like

to tweak your homestead to make its livestock more effective?

| This post is part of our Meat lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The bad news is that our Brinsea

EcoGlow chick Brooder we

love so much stopped working. It's getting power but the indicator