archives for 01/2013

I stopped picking broccoli

side shoots two or

three weeks ago. The plants are still putting out a few little

heads, but they get so damaged by heavy frosts that they're not worth

eating.

Luckily, Brussels

sprouts seem undaunted by weather in the teens. This is our first

year growing these tasty morsels, and we've found them to be easy

and delicious. There's room for

improvement in my methodology, though.

As our new,

experimental vegetable, Brussels sprouts got last dibs on prime garden

real estate after the broccoli and the cabbage. That means only

four seedlings were transplanted into the

garden on July 27, with the rest waiting another week. The

later-planted Brussels sprouts also went into the front garden, which

is far too shady for much production in cold weather since it's nestled

up against a north-facing hill. Small surprise we've only been

enjoying the rewards from those early and sunny plants (although the

late and cold plants are still doing fine and may churn out sprouts in

the spring).

As our new,

experimental vegetable, Brussels sprouts got last dibs on prime garden

real estate after the broccoli and the cabbage. That means only

four seedlings were transplanted into the

garden on July 27, with the rest waiting another week. The

later-planted Brussels sprouts also went into the front garden, which

is far too shady for much production in cold weather since it's nestled

up against a north-facing hill. Small surprise we've only been

enjoying the rewards from those early and sunny plants (although the

late and cold plants are still doing fine and may churn out sprouts in

the spring).

This year, I'm going to

start the Brussels sprouts a week earlier and get them all into the

garden by the middle of July (if I can find room). I'm also going

to put Brussels sprouts near the top of our list of important winter

crops, after kale, lettuce, and broccoli, but before Asian greens,

cabbages, and mustard. Finally, at Mark's request, I'll also be

growing lots and lots more. Maybe next winter, Brussels sprouts

will change from a special treat to a regular occurence on our plates.

Marco and Dirk brought up a good

point on yesterday's post in the comment section about proper blade

choice.

The blade in question was a

multi-purpose wood and metal, and yes it would have done better with a

pruning blade.

A portable reciprocating saw

like the DW

938 would be handy for cutting PVC pipe in hard to reach

places like under a sink.

I do like the easy unlocking mechanism for switching out blades. Our Skil reciprocating saw requires

a small wrench to loosen and tighten blades, which is a real pain when

that wrench is nowhere to be found.

Remember that locust

tree I'd been saving

as firewood insurance? It wasn't what I thought it was.

Black

locust is considered to be top-notch firewood because you get 112% as

much heat out of a same-sized log compared to red or white

oaks. In contrast, the most common trees Mark and I cut out

of our woods give only 75% (box-elder) to 83% (black walnut) as much

heat as oak, which means more work for less reward. Effort aside,

oak and locust fires are preferred because they keep going longer into

the night and put off more heat in the process.

Black

locust is considered to be top-notch firewood because you get 112% as

much heat out of a same-sized log compared to red or white

oaks. In contrast, the most common trees Mark and I cut out

of our woods give only 75% (box-elder) to 83% (black walnut) as much

heat as oak, which means more work for less reward. Effort aside,

oak and locust fires are preferred because they keep going longer into

the night and put off more heat in the process.

Unfortunately, I'm

reanalyzing that standing dead tree and figuring it might be sycamore,

which clocks in at only 80% as good as oak. I'm not sure why I

didn't take the multiple trunks into account before, which is a growth

habit common in sycamores but rare in black locusts. I guess I

thought the way the logs were so darn tough to split meant they were

locust, but it turns out sycamore has a spiral grain that makes

splitting a bear.

The easiest way to guess how

many BTUs you'll get out of a log of mystery firewood is to wait until

it's totally dry and pick it up. The lighter the wood, the less

heat you're going to enjoy when the wood burns. Bone-dry

box-elder is nearly as light as balsa wood, and our mystery tree isn't

much heavier. Meanwhile, both box-elder and our mystery wood work

great as kindling, which is another sign of low BTU --- harder woods

are tougher to light, unless they're resinous.

The easiest way to guess how

many BTUs you'll get out of a log of mystery firewood is to wait until

it's totally dry and pick it up. The lighter the wood, the less

heat you're going to enjoy when the wood burns. Bone-dry

box-elder is nearly as light as balsa wood, and our mystery tree isn't

much heavier. Meanwhile, both box-elder and our mystery wood work

great as kindling, which is another sign of low BTU --- harder woods

are tougher to light, unless they're resinous.

The fact I've been

burning light wood all winter would explain why we've been going

through it so quickly. Luckily, the shed's still mostly full, and

Mark discovered sycamore isn't terribly hard to split if you wait until

it's 20 degrees outside. If we ever run out of fallen, dead, or

in-the-way trees and start managing a woodlot, though, sycamore isn't

going to be involved.

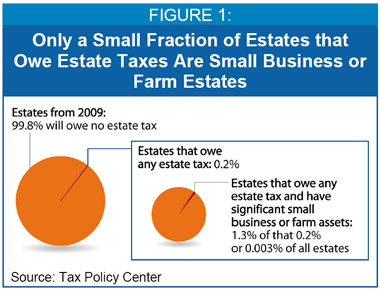

The most interesting part of

this week's selection in Folks,

This Ain't Normal was Salatin's chapter on inheritance taxes.

I'm surprised he didn't add property taxes to the list of money-related

regulations that make it tough for family farmers to keep the land in

agriculture, so I'm going to pretend he did and discuss both issues

today.

The most interesting part of

this week's selection in Folks,

This Ain't Normal was Salatin's chapter on inheritance taxes.

I'm surprised he didn't add property taxes to the list of money-related

regulations that make it tough for family farmers to keep the land in

agriculture, so I'm going to pretend he did and discuss both issues

today.

Salatin tells us that

his farm, bought by his parents in 1961 for $49,000, is now worth $1.5

million. Although a quick search of the internet suggests there

might be exemptions that would keep him from paying that tax, Salatin

posits that if he wants to keep farming the land after his parents die,

he needs to be prepared to pay $525,000 in inheritance taxes. He

does mention that there are workarounds to inheritance taxes if you get

the ball rolling early enough, but it is worth considering the

worst-case scenario, which often forces the offspring of deceased

farmers to sell the land to developers.

Similarly, I've read on

others' blogs of their astoundingly high property

taxes, often several thousand dollars per year, which make true

on-farm self-sufficiency impossible. For those of you looking for

land, I think it's worth keeping property taxes low by looking for an

ugly duckling property (as I explain in Trailersteading)

and by avoiding thinking of your dwelling as an investment that should

be increasing in value. But you clearly don't have those choices

if you're lucky enough to inherit a family farm.

Salatin is a libertarian, so he'd say the

solution to these problems is deleting taxes, but I think the issue is

deeper and has to do with ever-rising land prices. For example, in Salatin's

previous chapter, extensive quotes by Benjamin Franklin about the

differences between the young United States and Europe included this

gem:

Salatin is a libertarian, so he'd say the

solution to these problems is deleting taxes, but I think the issue is

deeper and has to do with ever-rising land prices. For example, in Salatin's

previous chapter, extensive quotes by Benjamin Franklin about the

differences between the young United States and Europe included this

gem:

Franklin goes on to explain that the early United States didn't have big manufacturing businesses because of "labor being generally too dear there, and hands difficult to be kept together, every one desiring to be a master, and the cheapness of land inclining many to leave trades for agriculture." In other words, cheap land made people want to farm rather than working for a boss, and I suspect the same would be true today. If Salatin wants lots of small family farmers back on the land, it seems the obvious issue to pursue is lowering land prices.

What makes land prices rise? I'm inclined to say the larger the population and the higher our standard of living, the more expensive the land, but I'm neither an economist nor a historian. What do you think about inheritance and property taxes (plus zoning and the other issues brought forth in this week's reading)? Is there a way to make it feasible for interested young people to find land to farm and for children to take over their parents' estates with ease?

We'll finish up Folks, This Ain't Normal next Wednesday. Meanwhile, you can read other Salatin-based musings in part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4 of the book club discussion. Thanks for reading along!

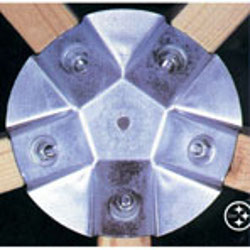

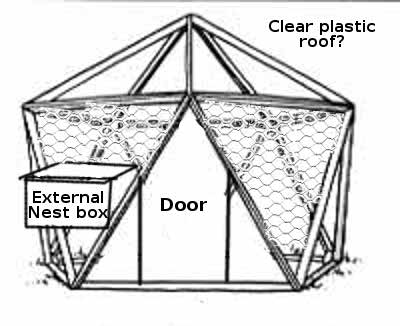

We've been talking about

projects for 2013, and chicken coop upgrade made it to the list.

I'm liking the simplicity of

this StarPlate building

method. If every other triangle flipped up it would make deep

bedding replenishment a breeze.

The StarPlate people claim a 15 percent

reduction in building material compared to a regular stick structure.

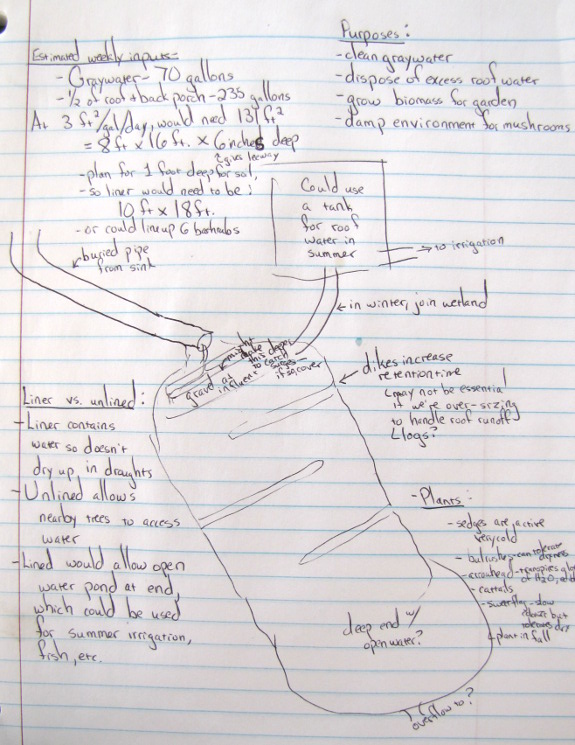

With the first phase of

the powerline

terrace complete, I

decided to move on to our next experimental project --- a greywater

wetland. When I started planning

this project in

October, I was considering installing a liner to turn the wetland into

a pond, but various readers' experiences talked me into keeping it

simple. Chances are, the ground will gley itself after a while

and will hold enough water to keep wetland plants happy. The less

long-term maintenance the wetland requires, the better, and unlined,

earth-filled wetlands seem to be winners there.

I was feeling more

loosey-goosey than usual, so I just dug and dug and dug with no real

plan for the finished product. Will I install a bricked-in outlet

at the top to keep water from eroding the soil there?

Probably. Will I use logs to divide the flow into a sinuous

pattern and dig deeper areas to make multiple pools? Maybe.

Will I try to make the final slope more than the current 0.5%?

Not sure.

I was feeling more

loosey-goosey than usual, so I just dug and dug and dug with no real

plan for the finished product. Will I install a bricked-in outlet

at the top to keep water from eroding the soil there?

Probably. Will I use logs to divide the flow into a sinuous

pattern and dig deeper areas to make multiple pools? Maybe.

Will I try to make the final slope more than the current 0.5%?

Not sure.

Other things I'm

pondering include building a little deck over the upper end to turn

into a laundry station so wash water can dump straight down into the

wetland (and so Mark doesn't have to mow around the wringer

washer). I definitely want to mash down the walls into a gentle

slope so they will be easy to mow over. We'll see what decisions

the day brings.

Today was the day I stopped

procrastinating on fixing the generator.

I was stuck on how to get the

bad gas out when Anna had the great idea of elevating the entire unit

with a bucket underneath. The gas drains out of the fuel

cut-off valve after unhooking the black rubber hose.

Hopefully some fresh fuel and

a new spark plug will bring it back to life, but I think I'll add half

a can of Seafoam to clean out any of the old fuel

residue.

I did a little reading

and pondering overnight and decided to change the shape of my greywater

wetland a bit.

It was approximately three feet wide and twelve feet long at the end of

the day Wednesday, but Create

an Oasis With Greywater recommends a width twice the

length. The upper end of the wetland is hemmed in, but I opened

it out a few feet down to perhaps five feet wide, then stomped on the

walls until they became a more gentle (hopefully mowable) slope.

The

next step was to consider how the water is going to get to the

wetland. We currently have two 3" pipes

running straight down from our kitchen sink. Even though it will

cost more to run both of them all the way to the wetland, keeping our

fast drainage seemed worth the hassle. We'll be using unflexible

PVC pipes that won't curve, so I pulled out some string to make

straight lines between the current sink outlet and the inlet of the

wetland.

The

next step was to consider how the water is going to get to the

wetland. We currently have two 3" pipes

running straight down from our kitchen sink. Even though it will

cost more to run both of them all the way to the wetland, keeping our

fast drainage seemed worth the hassle. We'll be using unflexible

PVC pipes that won't curve, so I pulled out some string to make

straight lines between the current sink outlet and the inlet of the

wetland.

When Mark buried the

waterline, the

project was painful because we wanted to get the lines deep enough they

wouldn't freeze. In contrast, my greywater lines are only being

buried for convenience, so we won't trip over them and can easily mow

over the area. Freezing won't be a problem because the water will

run straight out into the wetland, so my trench is only barely deep

enough to get the pipes underground.

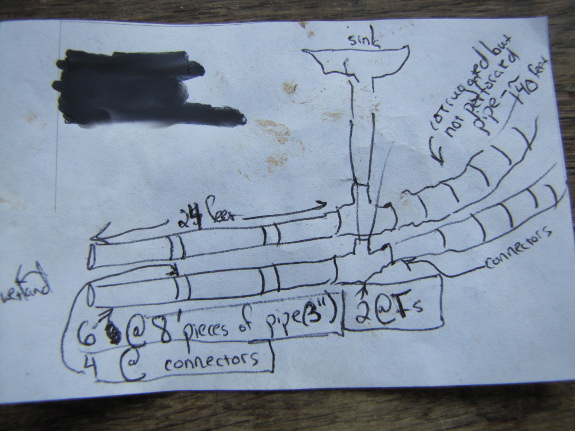

Here's Mark's shopping

list for today. We decided to make a T below the sink and let the

roof runoff come in there rather than running at third line for that

water. Heavy rains will hopefully flush out any gunk that may try

to build up in the lines between the sinks and the wetland.

I actually worked some

more on the inlet area of the wetland yesterday too, but this post is

already long enough, so I'll regale you with those details

tomorrow. Stay tuned!

I think it's been over 10

years since I first bought the Squeeze Wrench at a Flea Market and today it

finally got a chance to prove itself.

The Toyota Corolla seems to

have a misfire, and my first thought was to replace the distributor cap

and rotor.

Adding a small extension to

the Squeeze Wrench made for a near perfect

distributor cap removal tool and flipping it around lets you tighten in

the same cramped position.

The inlet of a greywater

wetland can be

trouble if you don't plan carefully. This is where the most tasty

(from a dog's point of view) gunk is going to land, so you want to

close it in to prevent nibbling. Water will also be gushing out

of the pipes with quite a bit of force here, so it's handy to make a

solid bottom in this area to prevent erosion.

There are lots of

designs for greywater inlets, but I wanted to work with what I have on

hand --- bricks

from the old chimney.

I loaded up a wheelbarrow full of the best ones and brought them down

to my budding wetland.

The pipes aren't in

place yet, but they'll be bringing water in from the top-left side of

the picture above. I simply laid bricks loosely on the ground and

put a few on the downhill side to further break up the flow.

I'd been saving these

fire bricks since they hold their shape much better in freezing, wet

conditions than the bricks that made up the bulk of the chimney.

I assume "Davis Savage," which is stamped on each fire brick, refers to

some long-ago local brick manufacturer. I only had enough fire

bricks to coat the bottom of the inlet, but that'll probably be the

spot that stays wet longest and will need to be strongest.

Some river rocks laid

loosely on top may or may not be enough to keep Lucy out. We'll

have to wait and see. I can hardly wait until these bricks moss

over and the greywater trickles down them like a tiny waterfall.

(Can you tell building

the greywater wetland is the most fun I've had all year?)

The Pro Line Hip Waders are leaking

at a crease in the material.

I tried a coat of silicone on

and around the cracks, thinking maybe when it dries it might end up

being a more flexible patch.

Another thought I have

concerns proper boot storage. Maybe the crease would have been less

severe if I was in the habit of storing the hip waders on some sort of

upside down manikin?

Every year, I plan to install

a bathtub, but I never do because I can't decide what I want it to be

like. Do I want to bathe inside by the fire, with the tub

converting into a padded bench for lounging? Or do I want the tub

outside so I can enjoy the sun on my back on summer days?

Probably we need both options, but this cast-iron rocket-stove

bathtub sounds like it might be a fun compromise.

Every year, I plan to install

a bathtub, but I never do because I can't decide what I want it to be

like. Do I want to bathe inside by the fire, with the tub

converting into a padded bench for lounging? Or do I want the tub

outside so I can enjoy the sun on my back on summer days?

Probably we need both options, but this cast-iron rocket-stove

bathtub sounds like it might be a fun compromise.

I emailed the designer

for tips since he included no more information than what you can see in the photo.

He replied to tell me that that the stove is built with cob, and that

that it draws quite well even with the long horizontal chimney

section. "Make sure to have pads under you when you are in the

tub or you will burn yourself," he added.

I'm not sure the thin

metal tub that came with our trailer would work with this system,

though, or whether it would melt right through. Perhaps a layer

of bricks between the stove and the chimney pipe would both decrease

the chance of burning a bare bottom and also keep the tub from

melting. What do you think?

We finally got the drinking

water problem resolved by replacing a clogged UV filter hose. The

delay was due to finding the right brass fittings.

These compression sleeve

parts cost a total of 25 cents at the hardware store.

I think the guy was giving me

a cost break and maybe a reward for repeated visits, but it's still

nice to buy something so useful with pocket change.

I love old barns.

I hardly remember the house I lived in from birth through third grade,

but the barn is still vivid, as are all of the other barns I've

explored over the years.

Mark and I enjoyed the

opportunity to visit Sarah's farm Saturday. We had lots

of fun hiking and hanging out, but most of my photos are of the barn.

I think this must be the

local style for livestock barns because Sarah's log barn is nearly

identical to the one on my aunt-in-law's farm one county over. I

was very jealous of the old manure still remaining in the stalls on

Sarah's property.

Sarah's corn crib looks

more modern, with its wire hardware cloth inside, but it still has a

very nice sense of style. While researching my root

cellar book, I

learned that corn cribs and root cellars both are probably designs

stolen from the Native Americans, then given a European twist. So

perhaps structures like this have dotted the Appalachian landscape for

thousands of years.

The golf cart

is having more and more trouble keeping a charge.

Coming up the hill by the

barn was too much for it a few weeks ago. We had to run an extension

cord and give it a boost before the golf cart could make it home.

We think the batteries are

six or seven years old. Perhaps it's time for a new set?

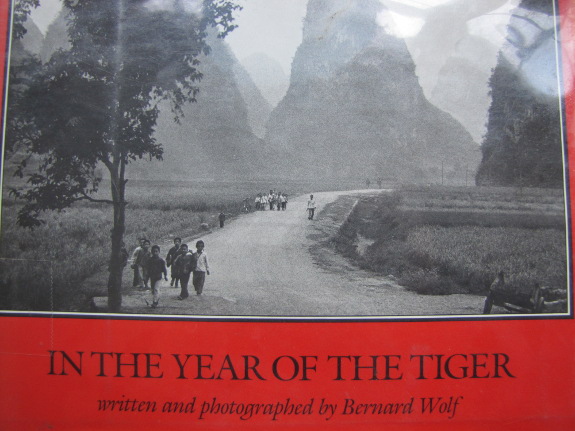

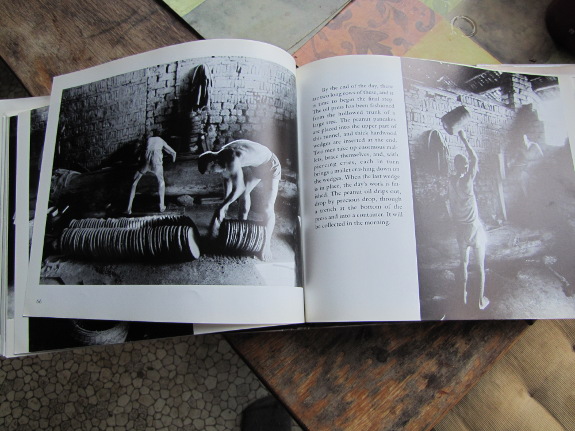

Mom found this beautiful

book being discarded from her local library. I can't imagine why

they'd get rid of such a fascinating text --- maybe because In

the Year of the Tiger

didn't fit into the children's section since it's really a

photojournalistic study for adults? I know I probably wouldn't

have gotten much out if it in fourth grade.

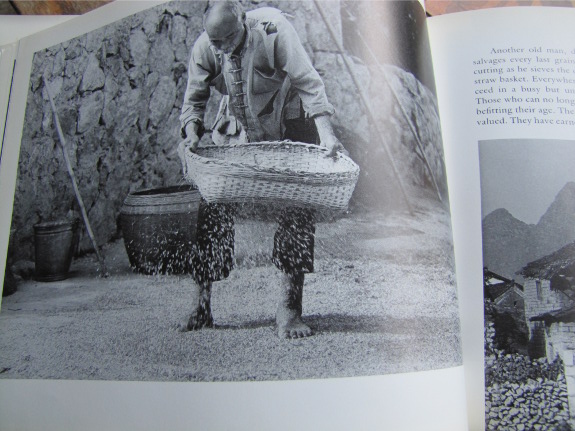

There's no real plot,

just amazing images from a Chinese village in the 1980s with

explanations of what's going on. This page says: "Another old

man, determined to be of uses, salvages every last grain from his son's

new rice cutting as he sieves the dregs through a fine-mesh straw

basket."

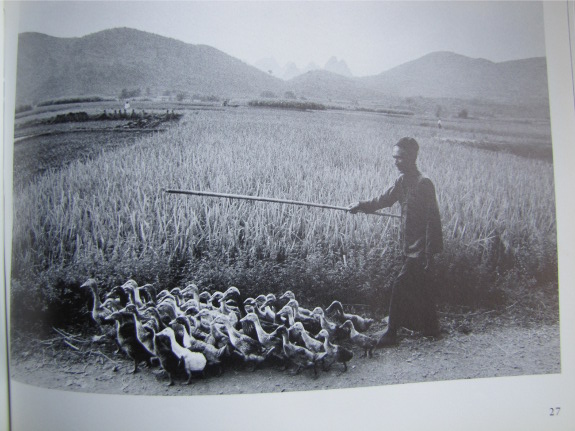

After this great shot of

ducks being herded home, the author explains that chickens are very

common in China but their meat is considered a delicacy despite the

animals' ubiquity. Most of the chickens are layers primarily kept

for their eggs.

The section on making

peanut oil in a hollowed out log, and then selling the cakes of

leftover peanut fiber for animal feed, was rivetting.

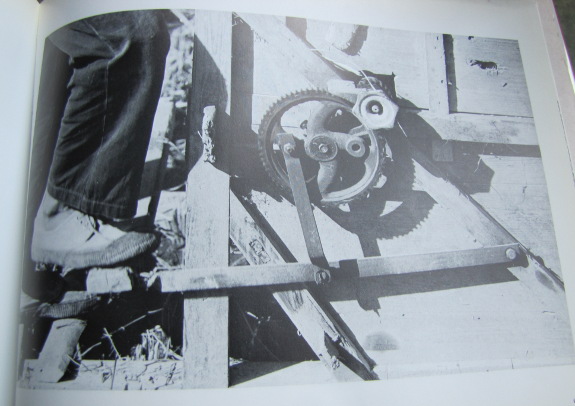

Here's a pedal-powered

threshing machine. One person can stand there and pump the pedal

while feeding in the grain. The same family had a separate

machine for winnowing the rice from the chaff that was very simple ---

just a place where you feed the chaffy grain into a chamber and a fan

pushes the chaff into one chute while the rice falls down another chute.

Overall, the book is

like Farmers

of Forty Centuries,

but more recent and with a lot more photos. I read In

the Year of the Tiger slowly over the course of a

couple of weeks and ended up feeling like I'd enjoyed a Chinese

farm-tour. If you ever stumble across a copy, I highly recommend

giving it a read.

When we last

made a rabbit post, we

were anxiously awaiting a litter of rabbits while mother rabbit was

preparing a nest in her nesting box. Sometime the night of the

post, our doe delivered her first litter. The litter was 11 kits,

one of which we lost the first morning. She delivered on a night

that was pretty cold and we surmised that the kit had wandered away

from the huddled litter and died of exposure. We had wrapped the

hutch in plastic and provided a incandescent lamp as a heat source, but

it wasn't enough. We later swapped out the lamp for a space

heater... probably throwing our cost per pound of rabbit equation off

due to electricity consumption. We had planned the timing of the

litter based on Easter though, so we had anticipated the possible

issues with the cold.

Since that first night we

lost another kit at about 4 days old, we think because it was

accidentally suffocated. It was away from the group and under the

hay, and we think the doe inadvertantly rested on it while tending to

the rest of the young.

Turns out our speculation in

the last post about the "bird's nest" depression in the hay was

correct. She had the litter exactly where we thought she

might. The kits were also a bit larger than we had expected at

about 4-5 inches long at birth. I think we both expected them to

be about half that size. They have also grown phenomenally

fast! At less than a week, they had beginnings of fur. At

about 10 days, their eyes began opening. At two weeks, they had a

full coat of fur. At less than one month old, they are several

times the size they were at delivery and are weaning themselves by

eating hay and rabbit food. They have also started learning how

to drink from the chicken waterer nipple, which is quite a feat when one

considers that they can barely reach it! Next time around, I

think the nursery hutch will have a lower nipple for the young.

Dawn also discovered it's quite

difficult to count the number of kits in the litter since when they

hear activity in the nest box they start jumping around like

crazy. They won't stop moving enough to be counted since they

think that activity means nursing time and they start actively search

out a mother and a teat.

Dawn also discovered it's quite

difficult to count the number of kits in the litter since when they

hear activity in the nest box they start jumping around like

crazy. They won't stop moving enough to be counted since they

think that activity means nursing time and they start actively search

out a mother and a teat.

I'm concerned about the fact

that these things are so cute that it's going to be tough when it comes

time to butcher. I guess time will tell how well we are able to

deal with that process. For now, we're just learning about what

it takes to have a litter of rabbits to care for, especially in the

cold.

Dawn also discovered rather

disconcertingly that once they were out of the nesting box that they could easily fall out

of the hutch. After a nerve wracking chase of one little fella

around the yard, she added a "rabbit retaining wall" to the door of the

hutch to help retain the frisky kits. Mom can be seen with three

of the kits along with the retaining wall in the photo above.

Shannon and Dawn

will be sharing their experiences with raising meat rabbits on Tuesday

afternoons. They homestead on three acres in Louisiana when time off

from life and working as a sys admin permits.

Aren't you afraid of mosquitoes during the summer? --- Rena

We live next door to a swamp,

but we don't get bitten much. Bats and dragonflies patrol the skies all

summer, keeping the outdoors habitable nearly all the time.

We do have a few insect

problems. In 2011, we started being plagued by deer flies whenever we

go in the woods during the dog days.

Gnats flying into our

eyes are another summer problem. They're not bad enough to keep us

indoors, though.

Part of Warre hive

methodology involves opening the hive as little as possible. In

past years, I've performed a winter

hive check on a warm

day to check on honey stores, but this year, I'm instead pressing

my ear up against the hive every week or two to take a

listen. Or, in this case, getting Mom to do it for me.

Part of Warre hive

methodology involves opening the hive as little as possible. In

past years, I've performed a winter

hive check on a warm

day to check on honey stores, but this year, I'm instead pressing

my ear up against the hive every week or two to take a

listen. Or, in this case, getting Mom to do it for me.

When you listen to each

side of each box, you can not only determine which box the main cluster

is in, but also where the bees are hanging out within the box. If

you're really good, you can also estimate colony size, but I'm not that

advanced in my bee-listening skills.

The bottom box of this

hive was always nearly empty, so the bees are hanging out in box number

two. Last month, they were toward the back of the box, but now

they've moved to the front.

I figure that's a pretty

good rate of eating through their stores, since the top box should

still be completely full of honey (I hope). In two months, we

should start seeing a few flowers, then everything bursts open at the

beginning of April. I hope our bees can hold on until then!

If you got annoyed by

Salatin's preachy writing style, I recommend skipping to the last two

chapters of Folks,

This Ain't Normal to

see the meat of his argument. His thesis is simple --- if our

government didn't regulate food, we'd have healthier dining choices.

If you got annoyed by

Salatin's preachy writing style, I recommend skipping to the last two

chapters of Folks,

This Ain't Normal to

see the meat of his argument. His thesis is simple --- if our

government didn't regulate food, we'd have healthier dining choices.

Why would lack of

oversight make our food better? The answer is twofold.

First, the current requirements make it very tough for small, local

farmers to break into the marketplace at all. Someone starting a

food-related business may have to buy expensive equipment to create a

federally inspected kitchen before they can whip up brownies for sale

at the local farmer's market, or they may have to adhere to even more

stringent requirements to open up a slaughterhouse and sell cut

meat. Economies of scale mean these issues are no big deal for

industrial food-processing operations, but government requirements sink

many mom-and-pop businesses. As Salatin wrote, "What started as a

regulation to control industry has instead become the tool industry

uses to eliminate innovation in the food marketplace."

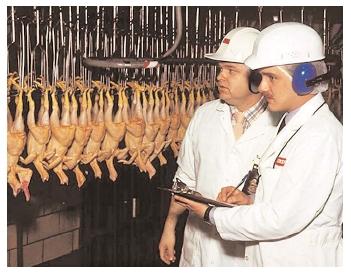

Meanwhile, those happy

USDA-approved stickers on our food make the consumer less inclined to

seek out the truth behind how their food was raised. Salatin

explains that in many cases, USDA-approval is merely about cosmetic

issues, such as the size of your eggs or the absence of tears in skin

of a chicken leg, but the consumer instead assumes the seal of approval

means the chickens were healthy and the food is good for us. If

the government didn't approve or disapprove of food, we would be

responsible for our own choices, which would send many of us out to

hunt down the farmer to see what their operation really looks

like. Once again, lack of government oversight would help the

little farmer, who is often the one passionate about soil and food

quality and is thus growing more nutrient-dense food. "The way we

create popular food literacy is to put people in the driver's seat,"

Salatin concluded.

Meanwhile, those happy

USDA-approved stickers on our food make the consumer less inclined to

seek out the truth behind how their food was raised. Salatin

explains that in many cases, USDA-approval is merely about cosmetic

issues, such as the size of your eggs or the absence of tears in skin

of a chicken leg, but the consumer instead assumes the seal of approval

means the chickens were healthy and the food is good for us. If

the government didn't approve or disapprove of food, we would be

responsible for our own choices, which would send many of us out to

hunt down the farmer to see what their operation really looks

like. Once again, lack of government oversight would help the

little farmer, who is often the one passionate about soil and food

quality and is thus growing more nutrient-dense food. "The way we

create popular food literacy is to put people in the driver's seat,"

Salatin concluded.

While I disagree with

many libertarian arguments, the food one has always made sense to

me. I would love to see food become a local, community endeavor,

where neighbors would know the confinement chicken operation wasn't

worth patronizing and where raw milk could be legally peddled at the

farmhouse door. Sure, some people would get sick from an

unmanaged food supply, but maybe fewer than get sick now from

regulations that often amount to window-dressing. What do you

think?

This is my last book

club post for a while, but you can read previous discussions of

Salatin's book in previous posts: part

1, part 2, part

3, part

4, and part

5. If you're

looking for more reading material, check out some of the books on my winter

reading list, or (if

you really get bored), you can even read my

books. Happy

reading!

Pantone may think the color of the year is Emerald, but Lucy's fond of

her new orange collar.

Most of the hunters we know are careful to get a good look at their

"deer", but we didn't want to risk Lucy getting shot.

Despite her new styling wardrobe, Lucy's still a tomboy and is always the

first one to the top of the mountain.

Well, I now know two methods

of rooting fig cuttings that definitely don't work for me --- in

a ziplock bag on top of a heat pad and in a pot of soil on top

of a heat pad. The fungal growth is pretty impressive, but the

cuttings are obviously dead.

Well, I now know two methods

of rooting fig cuttings that definitely don't work for me --- in

a ziplock bag on top of a heat pad and in a pot of soil on top

of a heat pad. The fungal growth is pretty impressive, but the

cuttings are obviously dead.

Actually, I suspect the

problem started even before I began trying to root the cuttings.

I had to cut the young wood before it was 100% dormant because a hard

freeze was coming and I needed to wrap

up the tree.

Perhaps the branches were too high in sugars (thus the fungal growth)

since they weren't fully asleep yet?

All is not lost.

Three little sprouts rooted the easy way, right at the feet of the

parent plant, and I have two

in my garden and one

in Mom's garden waiting for spring. Since there really is a limit

to how much space I have for fig trees, I suspect this propagation

method will do the trick. I'd still like to learn to root

cuttings just for geekiness sake, but I'm not too heartbroken over this

round of failures.

Anna made me a Meyer

lemon pie today for my birthday. The tree had perfect timing

ripening up its first fruit of the winter.

Her favorite pie is cranberry-raisin,

and cranberries are in season right around her birthday.

It got me thinking. Maybe there's a universal pie theory?

Does your favorite fruit pie match up with what's ripe around your

birthday?

Every winter, I flip through

past planners to make sure I don't forget any seasonal tasks in the

coming year. This year, I decided to spend a little more time now

and save time later by summing up the main events in this post.

Maybe it will help you get your homestead year in order too!

Every winter, I flip through

past planners to make sure I don't forget any seasonal tasks in the

coming year. This year, I decided to spend a little more time now

and save time later by summing up the main events in this post.

Maybe it will help you get your homestead year in order too!

January:

Winter

- Order seeds.

- Taxes.

- Writing.

- Fun projects.

- Mark the year's projects on planner.

February:

Frog month

February:

Frog month

- February 1 - start planting.

- Prune fruit trees and berries. Topdress those that didn't get deep bedding mulch this fall. Add mulch as needed.

- Rake mulch off asparagus beds at end of month.

- Cut logs for mushrooms and order spawn if expanding varieties.

- Grafting.

- Fix holes in pasture fences in preparation for chickens to be moved out of woods as grass begins to grow.

- Start saving eggs February 23 to go in incubator March 2.

Test heated brooder and clean outdoor brooder.

- Start cutting next year's firewood.

March:

Spring flowers

March:

Spring flowers

- Consider running laying flock under fruit trees this month to

kill bad bugs.

- Start serious garden prepping for spring --- weeding and topdressing. Continue planting from garden spreadsheet.

- Take quick hoops off fall crops.

- Check on worm bins.

- Inoculate mushroom logs.

- Chicks hatch March 23. Out on pasture in sunny spot ASAP.

- Wash incubator. Start saving eggs March 23 to go in incubator March 30.

- Consider adding another bee hive. If so, order or build

hive and find bee source.

- Take out bottom board and entrance reducers on bee hives.

Replace straw in quilt.

- Continue cutting next year's firewood.

April:

Chick month

April:

Chick month

- Prepare May garden beds.

- Haul in extra manure.

- Clean up scattered debris in yard and begin mowing.

- Move first set of chicks to coop. Check pastures for holes.

- Install packages of bees if increasing apiary.

- Chicks hatch April 20. Out on pasture in shady spot ASAP.

- Wash winter bedding and extra clothes.

- Set up irrigation.

- Train miniature apples.

- Sweep chimneys.

- Golf cart battery maintenance.

May:

Strawberry month

May:

Strawberry month

- Cut rye once blooming.

- Split bee hive(s).

- Major planting push.

- Mowing.

- Weed earliest spring crops.

- Plan summer and fall garden rotation. Order extra seeds.

- May 15 (or whenever last frost is obviously over) --- Uncover

figs and baby persimmons. Move citrus outside and topdress.

- Add new box to hive if necessary.

- Stake up overwintering kale (for seed) and asparagus.

- Train miniature apples.

- Continue winter laundry.

- Strawberry leather.

- Begin pruning and training tomatoes. (Weekly from now on.)

June:

Green month

June:

Green month

- Start picking cabbage worms and Japanese beetles.

- Harvest excess honey from last year.

- Strawberry leather.

- Harvest garlic.

- Harvest Eyptian onion top bulbs.

- Start freezing excess produce (broccoli).

- Contact straw source.

- Trellis cucumbers.

- Continue pruning and training tomatoes.

- Weed rest of spring crops.

- Mowing.

- Finish washing winter bedding and clothes.

- Car inspection.

- Start harvesting blueberries.

- Continue planting.

- Fertilize, mulch, and weed small perennials (strawberries, asparagus, rhubarb, Egyptian onions).

- Top off mulch around larger perennials and weed (or kill mulch)

as necessary.

- Finish getting this winter's wood under cover.

- Process chickens third week of June.

- Train miniature apples.

- Summer prune perennials.

- Harvest kale seeds.

- Add new box to hive if necessary.

July: Dog

days

July: Dog

days

- Continue picking cabbage worms and Japanese beetles.

- Continue freezine excess produce.

- Continue pruning and training tomatoes.

- Trellis more cucumbers.

- Start saving eggs July 13 to go in incubator July 20.

- Harvest poppy seeds, arugula seeds, and tokyo bekana seeds.

- Continue planting.

- Weed and mulch garden.

- Mowing.

- Save seeds (tomatoes, etc.)

- Continue pinching perennials (blackberries, black raspberries,

kiwi).

- Bring in garlic from drying racks.

- Harvest onions and carrots.

- Haul trash to dump.

- Finish mulching larger perennials.

- Refill worm bins with manure.

- Process chickens third week of July.

- Train miniature apples.

August:

Tomato month

August:

Tomato month

- Continue picking Japanese beetles.

- Continue freezine excess produce.

- Continue pruning and training tomatoes.

- Chicks hatch August 10.

- Harvest mung beans.

- Bring in onions from drying racks.

- Mowing.

- Weeding, planting, mulching.

- Train miniature apples.

- Replace straw in Warre hive quilt.

- Dig up large weeds (ragweed, etc.) before they go to seed,

especially in pastures.

- Start harvesting butternuts.

- Wash and put away incubator.

September:

Soup month

- Continue freezine excess produce (including lots of soup).

Dry extra tomatoes and make ketchup.

- Continue pruning and training tomatoes.

- Tie up berries.

- Hive check and varroa mite count. Feed bees if low on

winter stores.

- Harvest mung beans, sweet potatoes, and butternuts.

- Install light in chicken coop.

- Mowing.

- Weeding, planting, mulching.

- Train miniature apples.

- Process old hens as young ones start to lay.

- Put away sweet potatoes and butternuts.

- Close up screen door for winter.

- Haul in more sawdust for composting toilet.

- Put away seeds.

October:

First frost

October:

First frost

- Order new perennials for November and December planting.

- Continue feeding bees, if necessary.

- Mowing.

- Weeding, planting, mulching.

- Train miniature apples.

- Staycation.

- Move citrus inside.

- Harvest potatoes and cabbage.

- Start putting garden to bed.

- Rake leaves out of the woods.

- Cut tops off asparagus.

- Move chicks to coop and clean out brooder.

- Change to new side of composting toilet.

- Kill mulch new garden areas for next year.

November:

Fall

- Contact straw source.

- Rake leaves out of the woods.

- Process broilers first week.

- Dig carrots.

- Frost protect figs.

- Finish putting garden to bed.

- Put up quick hoops.

- Winterize - put away five gallon buckets, drain hoses, run

lawnmower and weedeater dry, put heated waterer in coop,

weather-stripping, plug in light in fridge root cellar.

- Install bottom board and entrance reducers in bee hives.

- Hunting season --- kill deer.

- Divide nonwoody perennials. Harvest echinacea roots.

- Mulch perennials.

- Plant new trees and shrubs.

- Plan garden rotation.

December:

Resting month

- Finish anything leftover from November.

- Soil test.

- Writing.

- Fun projects.

If you're a type-A list

maker like me, you might also like to download this

year's planting calendar. I hope it helps keep

you on track!

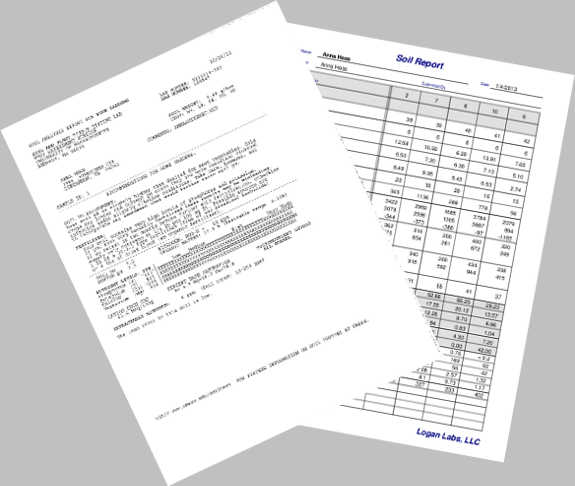

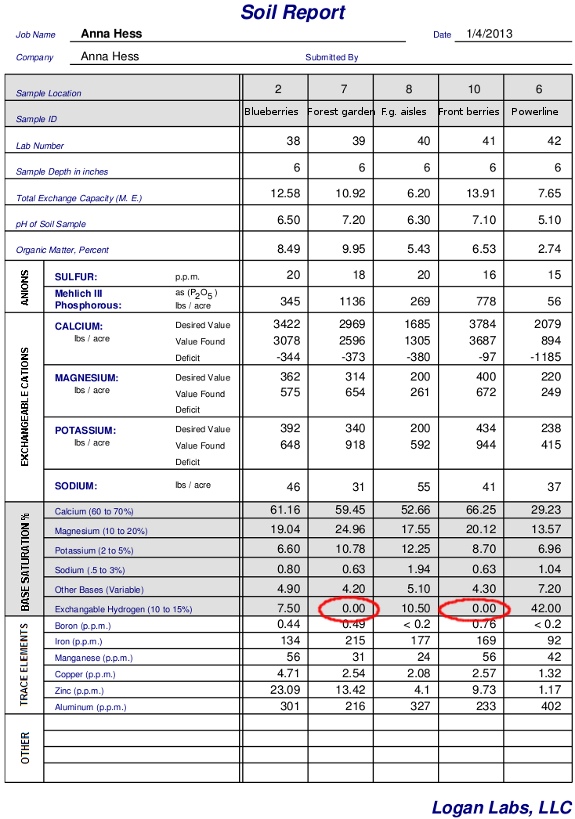

I got my soil

test results back,

and I'll be looking at them in much more depth than you probably want

to read about next week (and probably the week after) as a lunchtime

series. However, I thought it was interesting to see how

different test results can be from two different labs.

I doubt my soil has

changed very much over the last year, since I haven't added any major

amendments. And yet, this year's results show just about

everything much lower than last year's results showed, except for the

trace minerals, which are mostly higher.

(There are a couple of

mitigating factors to consider. I didn't take any samples from

the spots where I spread the gypsum. But I did take the

samples a little differently, testing deeper into the soil profile in

2012 because Solomon wanted a

six inch test depth for his analyses.)

| Mule 2011 | Mule 2012 | CP3 2011 | CP3 2012 | Back 2011 | Back 2012 | Front 2011 | Front 2012 | |

| pH | 7.55 | 6.9 | 6 | 5.9 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 7.3 |

| % OM | 17.7 | 4.87 | 8.2 | 5.48 | 15 | 7.82 | 14.6 | 8.95 |

| P (ppm) | 523 | 494 | 21 | 44.5 | 556 | 351.78 | 410 | 446.38 |

| K (ppm) | 774.5 | 404 | 351 | 306.5 | 615 | 298 | 875 | 487 |

| Ca (ppm) | 7555.5 | 2889 | 1643 | 1038 | 6801 | 1800.5 | 5772 | 2415 |

| Mg (ppm) | 989 | 441 | 213 | 175 | 926 | 299.5 | 743 | 421.5 |

| CEC | 70 | 20 | 15.6 | 9.88 | 56 | 12.9 | 47.1 | 17.63 |

| % Sat. Ca | 79 | 71 | 64.8 | 52.56 | 78.8 | 69.78 | 77.7 | 68.47 |

| % Sat. Mg | 16.95 | 18 | 13.8 | 14.77 | 17.6 | 19.35 | 16.4 | 19.92 |

| % Sat. K | 4.25 | 5 | 7.1 | 7.96 | 3.7 | 5.92 | 6.1 | 7.08 |

| Al | 6 | 215 | 14 | 402 | 6 | 220 | 7 | 247 |

| B | 1.5 | 0.67 | 0.5 | 0.29 | 1.3 | 0.56 | 1.1 | 0.62 |

| Mn | 22.2 | 41 | 4.5 | 30 | 24.4 | 43 | 19 | 47 |

| Zn | 8.05 | 43.57 | 12.5 | 6.64 | 7.5 | 17.07 | 8.5 | 38.34 |

| Cu | 1 | 3.19 | 0.9 | 2.03 | 1 | 2.8 | 1 | 3.46 |

| Fe | 2.15 | 248 | 2.2 | 153 | 2.1 | 215 | 1.7 | 236 |

| S | 126.5 | 24 | 33.8 | 19 | 109 | 20 | 100 | 19 |

Since these two labs

used different extraction techniques, it's not terribly surprising

their results varied. But you'd think there'd be one right answer

to how much sulfur (and everything else) there is in the soil. I

guess this is why Solomon recommends picking a lab and sticking to it

if you want to be able to tell the changes in your soil over time.

This

Sigma fitness monitor was

around 20 dollars and took less than 10 minutes to install.

It's a good way of keeping

track of elapsed time, average speed and more.

I was thinking the other day

it might also help to estimate power generated once I start

experimenting with pedal

power.

I was interested to see how

my mother's experience meshed with those of the people in Back from

the Land, so I gave

her my copy and quickly got a very negative reaction. "Maybe by

the 70s, the general climate was more disaffection, and just 'dropping

out,'" Mom emailed me, adding: "My own personal odyssey was...the aura

of 'peace farms' that I'd learned of thru Annie Upshure and the

Catholic Worker movement, safe places to try to work for peace."

I was interested to see how

my mother's experience meshed with those of the people in Back from

the Land, so I gave

her my copy and quickly got a very negative reaction. "Maybe by

the 70s, the general climate was more disaffection, and just 'dropping

out,'" Mom emailed me, adding: "My own personal odyssey was...the aura

of 'peace farms' that I'd learned of thru Annie Upshure and the

Catholic Worker movement, safe places to try to work for peace."

"Our actual venture was

to establish a commune 'in the heart of the people' (as in 'swim like

fish in the heart of the people')," Mom explained. Although she

wasn't part of the Vista program, my mother came south with several

people who were and she and others considered themselves "to be sort of

'independent Vistas.' We tried to live close to our neighbors,

admittedly only a few of the poorest families, actually ones who were

not farmers with their own land, but who were sharecroppers."

Mom grew up in

Massachusetts, so her first five years in southwest Virginia were all

about "putting down roots.... Because I was politically aware, I

could see my life as part of a bigger picture. And I was helped

by [my neighbors] in believing that learning how to live in the Mendota

area was viable." She added her "own twist" by working with

others on a Helping Hand Community Center, then by opening up an old

country store that served some community center functions.

"[Our neighbors] were a real

reason we were able to hang on for the ten years we did," Mom

added. "Because we were not in a commune, we were thrown on our

own resources." One of these days, I'll edit a fascinating video

interview in which Mom tells us much more about those devices, but

that's one of those back burner projects that has yet to see the light

of day.

"[Our neighbors] were a real

reason we were able to hang on for the ten years we did," Mom

added. "Because we were not in a commune, we were thrown on our

own resources." One of these days, I'll edit a fascinating video

interview in which Mom tells us much more about those devices, but

that's one of those back burner projects that has yet to see the light

of day.

I think we need to build

something like this to store our hip wader

boots in the future to prevent creasing which leads to leaking.

Image credit goes to the

Airforce Elmendorf Outdoor Recreation center where they rent hip waders

for 7 dollars per day.

The yurt came the rest of the way

down on Sunday. (I figured if I used the passive voice, our

memory of the event would involve less lugging of waterlogged wood

through the trees.)

All that was left behind

was a bare circle on the forest floor. Too bad I'm unlikely to

walk by there with anyone who hasn't heard of the yurt --- it would

make a fun, crop circle, April Fool's joke.

I'm wracking my brain

for something useful to do with that bare patch of earth, but I think

it will just be an experiment in how fast the forest reclaims

ground. I feel like the spot is too shady and too deer-prone to

plant anything edible, but if you've got a bright idea, now's the time

to throw it out there!

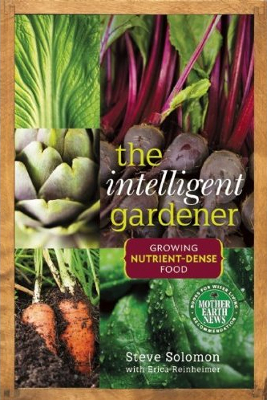

The

Intelligent Gardener,

by Steve

Solomon, is a

fascinating and well-written, if potentially

controversial, explanation of how to grow more nutrient-dense

vegetables

by balancing your soil. If you've heard of William Albrecht

and/or Michael Astera, but didn't feel comfortable wading through old

classics, Solomon's book is the quick and easy way to access the same

data.

The

Intelligent Gardener,

by Steve

Solomon, is a

fascinating and well-written, if potentially

controversial, explanation of how to grow more nutrient-dense

vegetables

by balancing your soil. If you've heard of William Albrecht

and/or Michael Astera, but didn't feel comfortable wading through old

classics, Solomon's book is the quick and easy way to access the same

data.

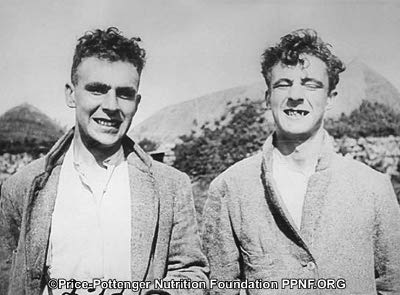

Steve Solomon stumbled

across the work of Albrecht after coming to

similar conclusions on his own. He and his family lived for nine

years in Oregon, where they grew most of their own food on worn-out

soil that was deficient in several major nutrients. As a result,

Solomon and his wife began to get sick, with lowered energy levels,

loose teeth, and soft fingernails. A six-month vacation in Fiji

created drastic changes in their vitality, due (Solomon believes) to

the local produce grown in soil fertilized by silt from volcanic

rocks. This experience led him to the work of Weston Price, who

argued that we really need four (or more) times the recommended daily

allowance of calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, iron, and vitamins A, D,

and E for best health. To get those high levels of vitamins and

minerals, Albrecht adds, you must garden in well-balanced soil full of

minerals.

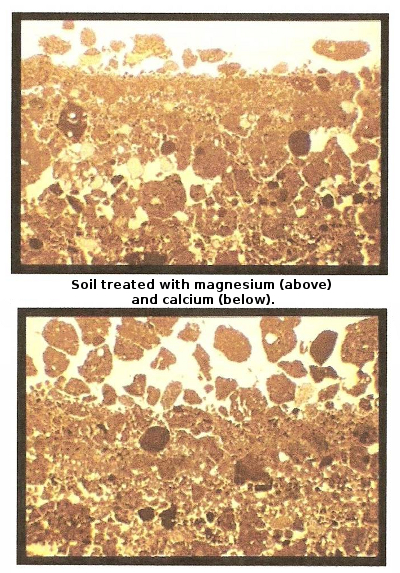

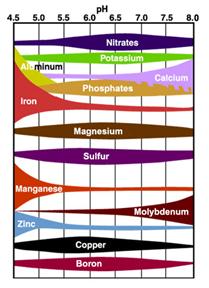

The conclusions Solomon

comes to from studying these older scientists

is in stark contrast to conventional organic gardening wisdom, most of

which derived from texts published by Rodale Press, so many of us might

find parts of Solomon's argument to be heresy. The Rodale way is

to focus on organic matter and pH only, adding compost and lime as

necessary until soil is in good shape. Solomon argues that this

focus on lime (often dolomitic, meaning lots of magnesium comes along

with the calcium) makes sense for  chemical farmers, since their

fertilizers acidify soil and leach calcium, but organic growers need a

more nuanced understanding of soil chemistry. Meanwhile, Solomon

posits that too much organic matter actually unbalances your

soil. (More on his solution to both of these issues in later

posts.)

chemical farmers, since their

fertilizers acidify soil and leach calcium, but organic growers need a

more nuanced understanding of soil chemistry. Meanwhile, Solomon

posits that too much organic matter actually unbalances your

soil. (More on his solution to both of these issues in later

posts.)

While The

Intelligent Gardener

is easy to read and presents the data very well, I still have questions

about the kookiness level of the information itself. For example,

all of the reasoning behind remineralizing soil is based on correlative

(not causative) studies, meaning that no one took the time to do a

side-by-side comparison of nutrient density of vegetables grown in

balanced and unbalanced soil. Solomon admits this fact freely,

when he writes: "Despite Albrecht's brilliance, it is quite possible he

succumbed to the same malady many garden writers suffer from ---

succeeding in his backyard and expanding it to include the whole

continent." But the information is worth considering with a

critical eye, so I'll be regaling you with the highlights of the book

as this week's lunchtime series.

This

post is part of our The Intelligent

Gardener lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

The creek flooded last night,

which made today silicone

patch testing day.

It worked at stopping water,

but a close inspection shows the silicone already starting to break

apart.

The hip waders are still better than the

alternative, especially when you add an outer layer of grocery bags to

your socks.

Even though my fig

cuttings kicked the bucket, things are starting to grow

inside. I went ahead and planted my tip-rooted

gooseberry, but have

been saving Mom's and Sarah's until I remember to bring their little

plants to their new homes. The seemingly-dead gooseberry cuttings

have been sitting in a sunny window, and I just noticed that this

little one is starting to leaf out! That means it will have to

wait to go into the ground until after the frost-free date, but also

that it will probably have more roots and will bear sooner than if I

had stuck it outside last fall.

Even though my fig

cuttings kicked the bucket, things are starting to grow

inside. I went ahead and planted my tip-rooted

gooseberry, but have

been saving Mom's and Sarah's until I remember to bring their little

plants to their new homes. The seemingly-dead gooseberry cuttings

have been sitting in a sunny window, and I just noticed that this

little one is starting to leaf out! That means it will have to

wait to go into the ground until after the frost-free date, but also

that it will probably have more roots and will bear sooner than if I

had stuck it outside last fall.

Next door, another pot

of sticks is sprouting leaves. A kind reader (T) sent me some

tindora --- tropical, perennial cucumbers --- to try out, and warm

weather this past weekend tempted one to put out leaves. I'm very

curious  to see whether this cucurbit

will be worth babying over the winter in future years, but it sounds

promising, with recipes available for baby fruits, ripe fruits, and

leaves.

to see whether this cucurbit

will be worth babying over the winter in future years, but it sounds

promising, with recipes available for baby fruits, ripe fruits, and

leaves.

T explained that he

developed this variety by crossing an all-male, ornamental variety with

a female plant on his neighbor's fence. The result was a sterile

variety that he reports is non-astringent, with cucumber-like, small,

green fruit that become soft, sweet, red fruits when fully ripe.

"In the summer, I cut it down in huge swaths to feed to the goats and

birds," he wrote, adding that this variety of tindora "could become a

really good forage for homesteaders and their livestock." We're

excited to try it!

Yesterday, I mentioned that Steve

Solomon's health improved when he spent six months in Fiji eating

nutrient-dense vegetables. The obvious question

is --- why isn't all soil as good as the stuff in Fiji?

Yesterday, I mentioned that Steve

Solomon's health improved when he spent six months in Fiji eating

nutrient-dense vegetables. The obvious question

is --- why isn't all soil as good as the stuff in Fiji?

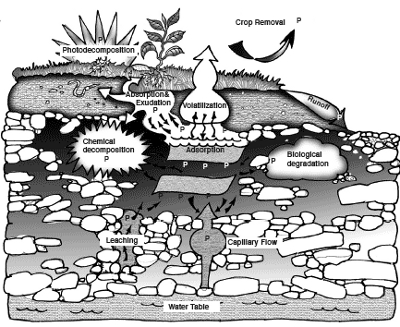

When it comes to soil

minerals, you need to understand both rocks and rain. The bedrock

that slowly dissolved to make up the soil in your garden will determine

which minerals were there to begin with --- some rocks are more

well-rounded than others. But even if your rocks are perfect,

lots of rain can still wash those nutrients out of the earth through a

process known as leaching.

As with rocks, not every

area is equal in terms of leaching potential. Hot, dry areas like

the American southwest have little or no leaching because all of the

water that hits the ground is sucked up by plants and transpired back

into the air through their leaves, or simply evaporates from the

earth's surface. At the other extreme, New England soils are

strongly affected by leaching because cold weather keeps water in the

ground once it hits, so water tends to gush through the topsoil and

into the groundwater, carrying minerals away with it. In general,

most of the soils in the eastern United States have been depleted by

leaching unless careful stewardship has kept organic matter levels high

at all times. (Humus holds onto the same minerals that rain tries

to wash away, keeping them cycling even if soils are flushed with

water.)

Another factor to consider is

age of your soil. Young soils have lots of minerals, but as soil

ages, the rocks dissolve and stop adding extra nutrients to the

soil. In addition, the cation

exchange capacity of

soils tend to degrade over geologic time. Here's where the

southeast is even worse off than New England --- we haven't had

glaciers down here recently to top off our rock reserves, so many soils

are old and low on minerals.

Another factor to consider is

age of your soil. Young soils have lots of minerals, but as soil

ages, the rocks dissolve and stop adding extra nutrients to the

soil. In addition, the cation

exchange capacity of

soils tend to degrade over geologic time. Here's where the

southeast is even worse off than New England --- we haven't had

glaciers down here recently to top off our rock reserves, so many soils

are old and low on minerals.

Assuming you aren't as

lucky as folks in Fiji, you'll need to remineralize your soil to get it

back in balance. This is why Solomon is down on the

compost-cures-all-ills approach to gardening. As he explained:

"Fertilizing a garden by composting local vegetation and animal manures

derived from that same kind of vegetation will only magnify the

regional soil imbalance." Time to get scientific and figure out

exactly what your unique soil really needs.

This

post is part of our The Intelligent

Gardener lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

The plans for the new chicken

coop upgrade now include an external nest box.

We might add some removable

panels that can be installed each Winter to block the cold wind.

I'm still undecided on what

type of roofing material to use.

It's been raining and raining

and raining, so I've huddled inside writing up (and through) a

storm. My root

cellar ebook still

needs a bit more data and photos, but a quick overview of using cover

crops in no-till gardens really wanted to see the light of day

immediately.

It's been raining and raining

and raining, so I've huddled inside writing up (and through) a

storm. My root

cellar ebook still

needs a bit more data and photos, but a quick overview of using cover

crops in no-till gardens really wanted to see the light of day

immediately.

Homegrown

Humus: Cover Crops in a No-till Garden probably won't give you much

new information if you've been reading my experiments here on the blog, but it

might be worth 99 cents to have all of the data summed up in one

place. I'm hoping the ebook will inspire folks to see how easy it

is to boost their organic matter levels in a no-till garden.

Here's the blurb:

Cover crops are a simple, cheap way to boost your soil's organic matter, to fight weeds, to prevent erosion, to attract pollinators, and to keep the ecosystem in balance. Unfortunately, most information on growing cover crops is written for people who plow their soil every year and are willing to spray herbicides. You can get all of the same benefits in a no-till garden, though, if you're clever.

Homegrown Humus details three no-till winners in depth --- buckwheat, oilseed radishes, and oats. Profiles of other species suggest gardening conditions when you might want to try out sunflowers, annual ryegrass, barley, rye, Austrian winter peas, crimson clover, or cowpeas as well.

Meanwhile, the book delves into finding cover crop seeds, planting cover crops in a no-till garden, and easily killing cover crops without tilling or herbicide use. Understanding the C:N ratio of cover crops helps determine how long to wait between killing cover crops and planting vegetables, as well as how to maximize the amount of humus you're adding to your soil.

Cover crops are an advanced gardening technique bound to increase your vegetable yields, but are simple enough for beginners. Give your garden a treat --- grow some buckwheat!

Next week, I'll post

excerpts as a lunchtime series. To read the rest,

you'll need to splurge

99 cents on the ebook (which can

be read on

nearly any device),

or wait until next Friday when I'm setting the price to

free so that my loyal readers can pick up a copy without paying.

Those of you who prefer a pdf copy can email me next Friday as well and

I'll

send your free copy that way instead. Thanks for reading (and

double thanks if you find the time to leave a review on Amazon)!

It's your glowing reviews of Trailersteading that inspired me to

whip out this ebook so quickly.

Before I go further into

Solomon's remineralization strategies, you have to know more about

those minerals I mentioned vaguely in my

leaching post.

Although there are a slew of minerals plants use in large and small

quantities, Albrecht (and those who have built on his work) are

primarily interested in the calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), potassium

(K), and sodium (Na). Albrecht believed that prairie soils

provide optimal crop nutrition, so he suggested we mimic the ratio

found there: 68:12:4:2. Other practitioners have suggested

slightly different values, such as 62:18:4:2 for sandy soil, or

85:5:2-4:1-2 if you're following the work of Victor Tiedjens and think

calcium is of most interest.

Before I go further into

Solomon's remineralization strategies, you have to know more about

those minerals I mentioned vaguely in my

leaching post.

Although there are a slew of minerals plants use in large and small

quantities, Albrecht (and those who have built on his work) are

primarily interested in the calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), potassium

(K), and sodium (Na). Albrecht believed that prairie soils

provide optimal crop nutrition, so he suggested we mimic the ratio

found there: 68:12:4:2. Other practitioners have suggested

slightly different values, such as 62:18:4:2 for sandy soil, or

85:5:2-4:1-2 if you're following the work of Victor Tiedjens and think

calcium is of most interest.

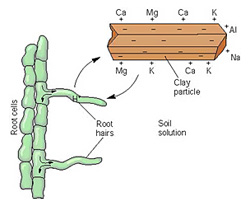

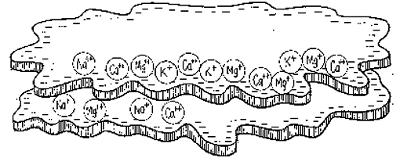

If you remember high

school chemistry, you may recall that these four minerals are all

cations, meaning they're positively charged and are attracted to

negatively-charged clay and humus particles. The amount of

negatively charged spots in the soil isn't unlimited, though, so

there's only so much space to go around (measured as the cation

exchange capacity),

and all cations don't cling equally tenaciously to the spots that are

available. Calcium is strongest, followed by magnesium,

potassium, and sodium, in that order, so if you dump masses of lime

(calcium) in the soil, calcium will fill all of the spots, bumping off

the weaker cations. Meanwhile, if you only add a moderate amount

of calcium, only the lowest cations on the totem pole will be bumped

off, so you'll end up with a higher ratio of calcium and a lower ratio

of sodium in the soil.

Even though we don't

talk about it much, the lowest cation on the totem pole is actually

hydrogen, which is pulled out of water to fill empty spots if there

aren't enough other cations to go around. If hydrogen has to fill

any negatively charged spots in your soil, that means you're soil is

acidic. Take a look at my soil test results above and notice that

the two samples without exchangeable hydrogen (circled in red) are also

the samples where the pH is greater than 7, meaning

the soil is alkaline instead of acidic.

This is also why adding

lime to your soil raises its pH. The extra calcium in lime knocks

hydrogen ions back into solution where they merge with the carbonate

ions from the lime to create water and carbon dioxide. Without

those extra hydrogen ions hanging around, the soil is no longer acidic.

The reason I've spent so long

on this chemistry is because it explains how you can change the ratio

of cations in your soil. Adding a stronger cation creates a

cascade of other cations being kicked off the negatively charged spots

in soil, and as long as you add lots of water to leach the unattached

cations from the water, those cations disappear into the subsoil and

leave the topsoil different than you found it. This can be handy

if you garden on clay (like I do) and if your soil contains too much

magnesium (like mine does), which tightens soil up and makes it

waterlogged. Those of you gardening near the coast who irrigate

with water high in salts will also find this handy since excess sodium

can be even more harmful to soil than excess magnesium since high

sodium levels tighten soil even more and can also be toxic to plants.

The reason I've spent so long

on this chemistry is because it explains how you can change the ratio

of cations in your soil. Adding a stronger cation creates a

cascade of other cations being kicked off the negatively charged spots

in soil, and as long as you add lots of water to leach the unattached

cations from the water, those cations disappear into the subsoil and

leave the topsoil different than you found it. This can be handy

if you garden on clay (like I do) and if your soil contains too much

magnesium (like mine does), which tightens soil up and makes it

waterlogged. Those of you gardening near the coast who irrigate

with water high in salts will also find this handy since excess sodium

can be even more harmful to soil than excess magnesium since high

sodium levels tighten soil even more and can also be toxic to plants.

Solomon's pet peeve has

more to do with nutrient-density than with soil texture, though.

He's found that leached soils are usually excessively high in

potassium, especially if you add hay, straw, or wood products to your

garden as compost or mulch. High potassium levels make plants

grow fast, but the produce is low in protein, is high in carbohydrates,

and is usually deficient in calcium and phosphorus. Livestock who

eat plants grown on high-potassium soil gain weight but don't breed

well, and people who eat from that type of soil tend to gain weight and

have health problems as well. Stay tuned for more details on how

to rebalance your soil for optimal nutrition.

This

post is part of our The Intelligent

Gardener lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

My Muck Chore boots are just over a year old.

They're holding up nicely

with zero damage and a high comfort rating.

I wouldn't be surprised if

they last over 5 years at this rate!

I've stopped reporting

on all the little floods --- it barely impacts our lives nowadays when

the creek hits the top of its banks. But when the water starts

flowing out of the creek and into the floodplain, the power of water is

too inspiring to ignore.

Our movie-star neighbor

wants to help us build a swinging bridge and Shannon got us started on

a zip-line, but the honest truth is that I doubt either of those

projects will ever come to fruition. The reason? I really

like being flooded in.

As a side note, the

analytical side of me started wondering if there was a pattern to our

floods. I'm sure I'm missing a few that didn't make the blog, but

here are the big ones I've recorded:

- March 6, 2004

- December

10, 2008 (small)

- December

17, 2008

- January 7, 2009

- September

26, 2009

- December 10, 2009

- August

20, 2010 (small)

- March

1, 2011

- March 7, 2011

- January

12, 2012 (small)

- March 4, 2012

- December

28, 2012 (small)

- January 16, 2013

Isn't it interesting how

the dates seem to cluster together? The second week of January is

flood time, and so is the first week of March.

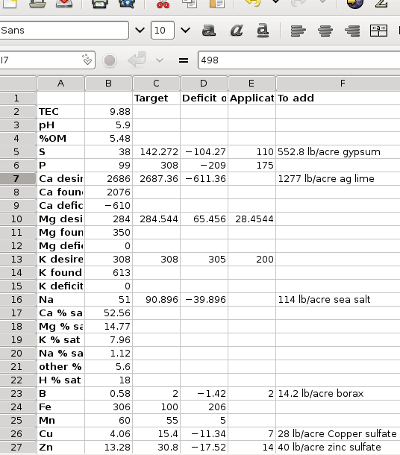

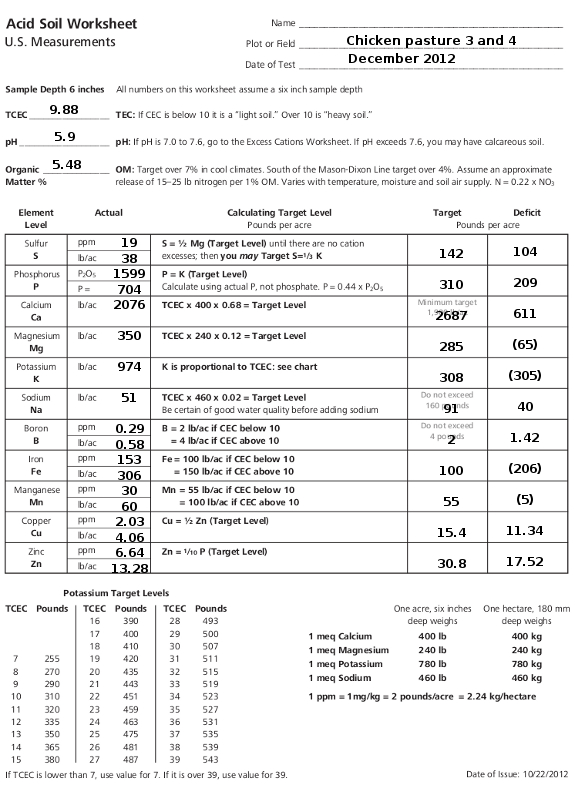

Before I dive any deeper into

soil science, I thought I'd walk you through filling out Solomon's soil

analysis worksheets (which you can download

for free here).

You'll notice there are actually six pages of worksheets in that file,

which consist of two pages each for acidic soils (pH less than 7),

"excess cations" soil (pH 7 to 7.6), and calcareous soil (pH greater

than 7.6). I actually find it much easier to make a

spreadsheet page for each soil sample since the program can do the math

for me, but I'll fill out a worksheet below to help you get an idea of

the process.

Before I dive any deeper into

soil science, I thought I'd walk you through filling out Solomon's soil

analysis worksheets (which you can download

for free here).

You'll notice there are actually six pages of worksheets in that file,

which consist of two pages each for acidic soils (pH less than 7),

"excess cations" soil (pH 7 to 7.6), and calcareous soil (pH greater

than 7.6). I actually find it much easier to make a

spreadsheet page for each soil sample since the program can do the math

for me, but I'll fill out a worksheet below to help you get an idea of

the process.

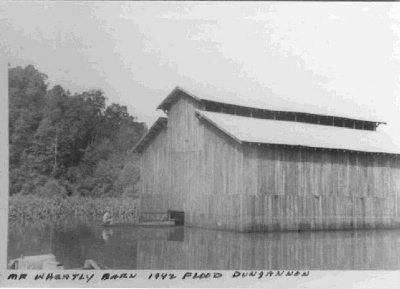

Since I sprang for a

test from Logan Labs, as

Solomon recommended,

it's pretty simple to fill out the column of actual amounts. The

only tricky parts are:

- You need to convert from ppm (parts per million) to lb/acre (pounds per acre) for certain readings. Solomon explains that you simply multiply ppm by 2 to get lb/acre, which I'm a little dubious about. His reasoning is that we sampled our soil to a six inch depth, and soil scientists estimate that amount of earth weighs about two million pounds per acre. When I start cancelling units in the conversion, though, I feel like there should be something factored in to take the atomic weight of each mineral into account, but I stuck to Solomon's math. (Roland, help?)

- Logan labs reports phosphorus pentoxide instead of elemental phosphorus, so you need to multiply their result by 0.44 to get lb/acre for phosphorus.

The target column is a

little more complex, but is mostly basic multiplication. The one

portion that might cause a hiccup is potassium (K) --- you get that

amount from the chart at the bottom-left of the worksheet based on the

TCEC of your sample. Similarly, boron, iron, and manganese

targets are based on TCEC, as is explained in the "calculating target

level" column.

Finally, you subtract the

actual amount of each element (in lb/acre) from the target amount to

figure out how much excess or deficient you are. Since Solomon

labelled the last column "deficit", I put excesses in parentheses.

Finally, you subtract the

actual amount of each element (in lb/acre) from the target amount to

figure out how much excess or deficient you are. Since Solomon

labelled the last column "deficit", I put excesses in parentheses.

The sample I used is a

pasture that has been grazed with chickens for a couple of years with

no other amendments, so I figure it's probably similar to the soil you

might find in a new garden spot. You'll notice the soil is acidic

and a bit low on organic matter, without as much capacity for cations

as you'd like, and it has too much of a few nutrients but too little of

some others. Tomorrow, I'll move on to the back side of this

worksheet to show you how to deal with those excesses and deficits.

This

post is part of our The Intelligent

Gardener lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

The Swamp Bridge started to float away today, but

got stopped by the now partially submerged golf cart.

This is shaping up to be our biggest

flood since moving here!

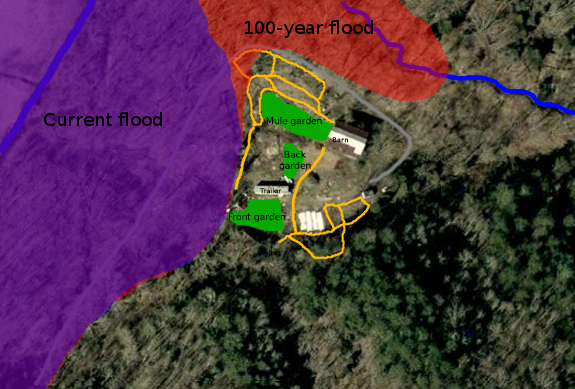

I'm pretty sure our

current flood is the

biggest one since we've moved to the farm, but you shouldn't be alarmed

--- we won't be getting our feet wet any time soon. We live up on

an abruptly-raised plateau that allows us to survey the floodwaters,

but we'd need an astounding amount of rain for the water to get up this

high. In fact, we aren't even at 100-year flood levels yet.

Old-timers in the area

tell me they remember when a flood extended all the way to the old

house, which used to sit on the south side of our front garden. I

can't really imagine that much water, and suspect those old-timers

might have the house confused with another one back in this holler, but

it's possible.

Besides the alligator swamp

bridge floating out

of place (already happened), the most-likely flood event we'd have to

deal with is evacuating the chickens from their current coop to the one

we usually use for broilers. During a break in the rain, our

flock was out foraging at the edge of the floodwaters, but they soon

settled back on their roosts to wait out the storm.

Even chicken-evacuation

is unlikely. Instead, we're hoping the floodwaters recede before

we run out of stockpiled fruit and library books, and before our chicken waterer customers get antsy.

Other than those three things, we're pretty much self-sufficient up on

our island.

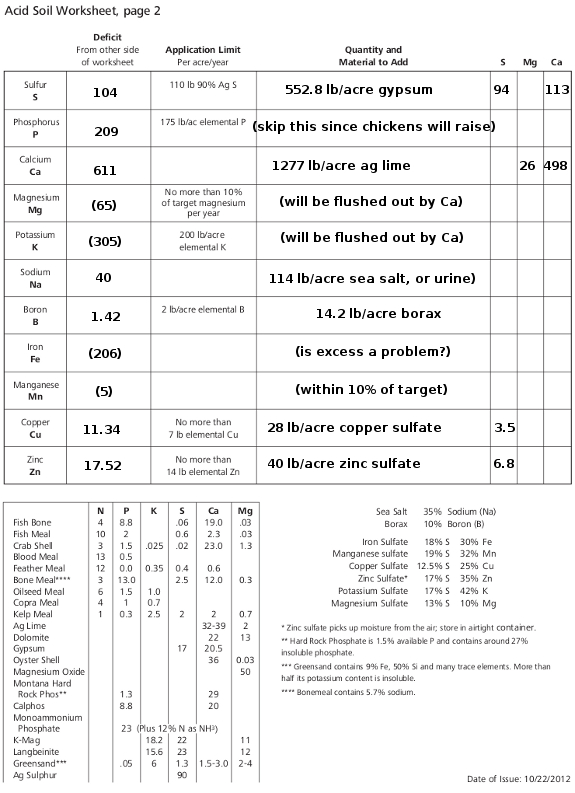

The second page of Solomon's soil worksheet shows how to create a unique

prescription of additives to get your soil back in balance. Once

again, I prefer a spreadsheet to do my math for me, but I'll work

through the prescription for yesterday's soil sample to help you

understand the process.

The first step just

consists of copying the numbers from the last column of the

other side of the worksheet to the first column of this

worksheet. Anything within 10% of the target amount can be left

alone, but we'll need to come up with a plan to decrease larger

excesses and fill up larger deficits. To do so, choose amendments

from chapter six of The

Intelligent Gardener

and add amounts until the final application rate of each element comes

out the way you want it to.

It's

usually best to start at the bottom of the chart since Solomon

recommends using sulfate fertilizers to address any deficiencies in

iron, manganese, copper, and zinc. The sulfur that these

fertilizers bring along for the ride will decrease the amount of sulfur

you'll need to add at the top of the chart in the form of ag sulfur or

gypsum. Solomon has included a handy reference chart at the

bottom of the worksheet showing the percent of each element in various

fertilizers, and the last three columns help you keep track of how much

sulfur, magnesium, and calcium come along for the ride in fertilizers

intended for other purposes.

It's

usually best to start at the bottom of the chart since Solomon

recommends using sulfate fertilizers to address any deficiencies in

iron, manganese, copper, and zinc. The sulfur that these

fertilizers bring along for the ride will decrease the amount of sulfur

you'll need to add at the top of the chart in the form of ag sulfur or

gypsum. Solomon has included a handy reference chart at the

bottom of the worksheet showing the percent of each element in various

fertilizers, and the last three columns help you keep track of how much

sulfur, magnesium, and calcium come along for the ride in fertilizers

intended for other purposes.

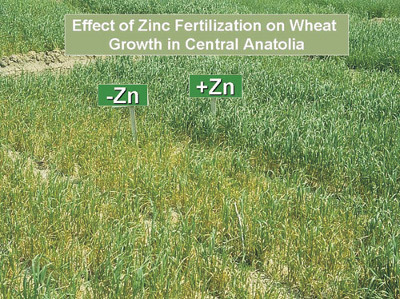

So, for zinc, you'll