archives for 12/2012

I hear from a lot of folks

who give up on drying

their clothes outside

in the winter. But once you buy a dryer, there's often no turning

back. First you toss your clothes in the dryer on frigid January

days, but soon even an overcast spell in June has you visiting the

indoor energy hog instead of just waiting for pretty weather.

I hear from a lot of folks

who give up on drying

their clothes outside

in the winter. But once you buy a dryer, there's often no turning

back. First you toss your clothes in the dryer on frigid January

days, but soon even an overcast spell in June has you visiting the

indoor energy hog instead of just waiting for pretty weather.

Since I stubbornly

refuse to set foot on that slippery slope, I'm stuck drying our clothes

outside all winter...and it's really no big deal. The waterline

froze the night before I chose to start our November laundry, so I

couldn't fill the wringer

washer until mid

afternoon, but our clean clothes still dripped most of the moisture out

that evening before freezing solid overnight. As soon as the sun

came out, they were sublimating moisture even from their frozen

surfaces, and then the sunny afternoon thawed the fabric enough that I

could flip each item over. That night, I put away all except the

heaviest towels, jeans, and fleece tops, and the next evening

everything was ready to come in.

Yes, it technically took

a bit over 48 hours to dry our clothes, but what's the hurry? Your annual estimated savings from hanging clothes on the line is

$100 for the equipment (depreciating value of the dryer) plus $150 in

electricity, and the extra work during extended winter drying amounts to no more time than you'd spend checking a rising loaf of bread.

Do you dry clothes

outside in the winter? Do you have any tips for folks who want to

try but are afraid of the cold?

These sub freezing mornings

make cinder

block stepping stones unsafe.

Much safer to wear Muck boots and walk through the creek where

the bottom is free of ice.

The great thing about

plants that tip layer easily is that you're likely to end up with extra

plants with absolutely no work on your part. Blackberries

and black raspberries

are probably the example you're most familiar with --- if you're not

careful, long canes of each will curve back down to the ground and root

at the end. But, as I learned this year, gooseberries fit into the same category.

We've been working to

get rid of weeds in our blueberry and gooseberry patch this summer,

which meant repeated weeding and mulching until the unwelcome plants

gave up the ghost. During one round of mulching, I accidentally

poured rotting wood chips on top of a few branches of my Poorman

gooseberry. Coming back around for a last weeding job in

November, I tugged at these branches...and found they'd grown

roots. All I had to do was clip off each branch above the rooted

section and pot it up to turn that into a new plant.

(By the way, Mom and

Sarah, your gooseberries are waiting on your convenience --- don't

forget to take them next time you see me! They're at the southern

limit of their range here, so choose them a cool, damp, partly shaded

site.)

I could have put the

little gooseberry cuttings straight into the ground, but I didn't have

a spot picked out for mine and was a bit afraid such a small plant

would lose its footing in the winter soil's freeze/thaw if I didn't

mulch it extremely carefully. So I slipped the gooseberry pots

into the citrus growing area in Mark's room --- maybe he won't notice?

It took Lucy about a week to

figure out her dog house now has a thermostatically controlled heating

pad to take the chill off the really cold winter nights.

The pad won't kick in till it

gets cold enough and uses only 80 watts.

Several folks report

that they root their hardwood

fig cuttings inside

over the winter, so I decided to give it a shot. Step one seems

to consist of wrapping the cuttings in damp  newspaper and then in a

ziplock bag and placing the cuttings in a warm spot for a couple of

weeks until roots begin to form.

newspaper and then in a

ziplock bag and placing the cuttings in a warm spot for a couple of

weeks until roots begin to form.

"Warm place" is the

operative word. One week into my experiment, with the cuttings on

top of the fridge, the one year old twigs were already starting to mold

instead of sprouting roots and leaves.

I got a little stuck

trying to figure out where in our house stays above seventy degrees day

and night before I remembered the

heating mat I use to grow sweet potato slips in the spring. It'll

definitely use less energy to just heat the cuttings than it would to

keep any part of our living space at "room temperature", and I'm

hopeful a couple of weeks on the mat will get those figs growing.

Any other fig rooting

tips from the experts out there?

We like the Trake garden tool so much we ordered an

extra.

I was using the new one back

in June and somehow lost it, which was a real bummer and often haunted

me when I would walk past the blueberries.

Turns out Lucy must have

"borrowed" it when I wasn't looking and then thought it would be better

to bury the evidence instead of putting it back in its designated spot.

Makes me wonder how many other tools are buried at various places

around the garden?

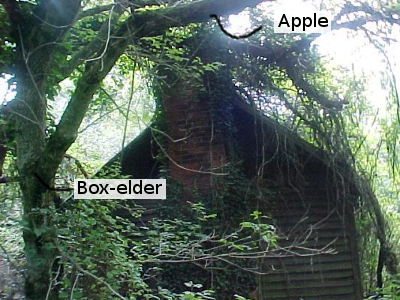

The

most recent owners of our farm before us had a standard apple tree

growing right beside their house. I figured that a house apple

was likely to be a delicious local heirloom, but although we really

wanted to keep it, the tree was too old and diseased to save. (If

I'd known as much about trees then as I do now, I would have grafted

some twigs onto new rootstocks to safeguard the variety, but hindsight

is always 20/20.)

The

most recent owners of our farm before us had a standard apple tree

growing right beside their house. I figured that a house apple

was likely to be a delicious local heirloom, but although we really

wanted to keep it, the tree was too old and diseased to save. (If

I'd known as much about trees then as I do now, I would have grafted

some twigs onto new rootstocks to safeguard the variety, but hindsight

is always 20/20.)

Even

though the apple perished without feeding us a single fruit, its body

has been feeding our garden ever since. The wood was too punky to

burn by the time we cut it up, but the rotting biomass has helped

increase the tilth of our blueberry beds. Last winter, I gathered

stump

dirt out of what

remained of the tree to start seedlings inside, and this fall I've

decided to let the rest of the stump become an instant, high quality

raised bed for my gooseberry

sprout.

Even

though the apple perished without feeding us a single fruit, its body

has been feeding our garden ever since. The wood was too punky to

burn by the time we cut it up, but the rotting biomass has helped

increase the tilth of our blueberry beds. Last winter, I gathered

stump

dirt out of what

remained of the tree to start seedlings inside, and this fall I've

decided to let the rest of the stump become an instant, high quality

raised bed for my gooseberry

sprout.

In many forests, nurse

logs and stumps form natural beds to help along new baby trees, so I'm

just mimicking nature with my action. However, I want nature to

progress a little faster than it would in the wild, so I talked Mark

into cleaning out the deep

bedding in the

broiler coop to add more nitrogen to what is otherwise a low fertility

garden spot.

While we were at it, we

spread deep bedding on bare patches elsewhere in the blueberry beds,

probably covering about a quarter of the currently mulched area.

All that high nitrogen chicken manure will probably be enough to feed

the blueberries all summer --- the trick will be remembering those

plants got a fall feeding and not topdressing with more compost come

spring. I clearly need some kind of data-collection to go with my

new haphazard

mulching campaign so

everyone gets a fair shake when it comes to feeding.

While we were at it, we

spread deep bedding on bare patches elsewhere in the blueberry beds,

probably covering about a quarter of the currently mulched area.

All that high nitrogen chicken manure will probably be enough to feed

the blueberries all summer --- the trick will be remembering those

plants got a fall feeding and not topdressing with more compost come

spring. I clearly need some kind of data-collection to go with my

new haphazard

mulching campaign so

everyone gets a fair shake when it comes to feeding.

The weather this past

November was a lot more like December, but once the calendar flipped

over, we got a welcome thaw. As the day warmed up, I was

astonished to notice that the ouside world had smells again! I

guess when the ground is frozen, odors have a hard time reaching our

noses.

The weather this past

November was a lot more like December, but once the calendar flipped

over, we got a welcome thaw. As the day warmed up, I was

astonished to notice that the ouside world had smells again! I

guess when the ground is frozen, odors have a hard time reaching our

noses.

Although I enjoyed most

of the scents, I was a bit afraid to drop by the new composting

toilet because the

goal there is a complete absence of odor. I shouldn't

have worried. All of that sawdust we've been dropping down the

hole has done its job --- the composting toilet is currently smell-free.

The next test will wait

until summer --- presence or absence of flies. After that, we

won't get more feedback until two years from now when I scoop this

fall's poop under the fruit trees as compost.

That's assuming

something doesn't go drastically wrong. I'll be sure to report if

there's any seepage, slumps, or other disasters.

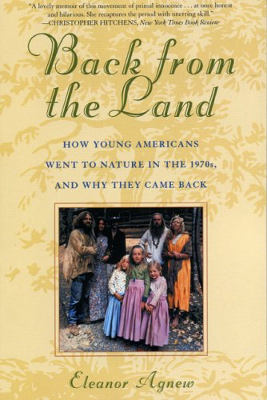

Mark doesn't generally read

along with our book clubs because I tell him the

highlights of every text over the dinner table. As I related Salatin's

pointers from this week's selection, Mark replied, "So, he's a

choir preacher, right?"

Mark doesn't generally read

along with our book clubs because I tell him the

highlights of every text over the dinner table. As I related Salatin's

pointers from this week's selection, Mark replied, "So, he's a

choir preacher, right?"

I hadn't thought of Joel

Salatin that way (although his scattered chapters do feel a bit like

daily sermons), but in retrospect, I think Mark might be right.

For example, take the essay "No Compost, No Digestion", the thesis of

which is that real food will rot if left on the counter for a couple of

days, while items souped up with preservatives are no better for our

digestive systems than they are for the air-borne microorganisms that

turned them down. If you're not already sold on the idea that

diet soda and ultra-processed food is bad for you, would Salatin's

chapter open your eyes in any way?

On the other hand, can we

ever do anything other than preach to the choir? I'm curious to

hear how you all (my choir, who I assume probably agrees with most of

my rants or you wouldn't stick around) came around to this point of

view. Was it childhood indoctrination informed by reading and

experimentation (my answer), or did you stumble upon the ideas of

ecological food production as an adult?

On the other hand, can we

ever do anything other than preach to the choir? I'm curious to

hear how you all (my choir, who I assume probably agrees with most of

my rants or you wouldn't stick around) came around to this point of

view. Was it childhood indoctrination informed by reading and

experimentation (my answer), or did you stumble upon the ideas of

ecological food production as an adult?

If I were Salatin's

adviser, I think I'd recommend that his next book take an entirely

different tack if he really wants to change the world. Include

lots of glossy photos of happy pastured pigs, chickens, and cows and

write a children's picture book with just the facts. Or hire a

publicity firm as Salatin reported one college campus did to train its

students to enjoy chewing pastured meat.

Meanwhile, I'll keep

reading his daily devotionals. Tune in next Wednesday to discuss

chapters ten through thirteen (up through "Grasping for Water"), and

don't forget to read over the interesting

comments on the first week's selection if you haven't already.

Two things I didn't consider when building chicken

coop #1 were easy egg access and deep bedding.

We might replace it with a

bigger coop in the future, but it's hard getting motivated to fix

something that's just a little broken when there's several more

important projects on the list.

While I'm obsessing over

mulch, I thought you might enjoy seeing a followup about my wingstem

and ragweed mulch

from the middle of June. This is far from a controlled experiment

since three rounds of chicks spent their childhood scratching under the

so-mulched raspberries and

blackberries, adding extra nitrogen and stirring things up for

ultra-fast composting. So I wasn't surprised to see that all of

the weed leaves had completely disintegrated and even the stems were

quickly disappearing into the dirt.

so-mulched raspberries and

blackberries, adding extra nitrogen and stirring things up for

ultra-fast composting. So I wasn't surprised to see that all of

the weed leaves had completely disintegrated and even the stems were

quickly disappearing into the dirt.

Without the cardboard

layer underneath, I suspect the mulch wouldn't have held out as long as

it did, but there were actually very few living weeds under the berry

bushes when I weeded this week. And the fall raspberries were

huge, delicious, and copious down there, perhaps just from the chicken

manure, but also perhaps due to the slowly decomposing weed

carcasses. So even though the mulch was a bit short-lived and

needed to be topped off before winter, it's probably worth doing again.

The results in the woods

(the source of the wingstem and ragweed) were equally striking --- no

more tall weeds. This might be a pro or a con, depending on what

you're trying to do with an area. If you want to get rid of tall

weeds so you can grow shorter plants livestock will eat more readily,

it might be a great idea to cut the wingstem and ragweed just before

they bloom in June; but if you enjoy the flowers for your honeybees,

this might not be such a good source of mulch.

I'm not sure the effort

to biomass ratio is good enough to make this a regular part of our

mulching campaign, but I'm going to keep it in the running.

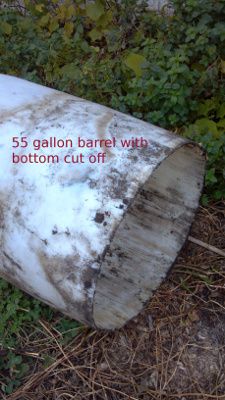

A tip for city dwellers needing

to compost in limited space: I highly recommend 5 gallon pails

with gamma seal lids, bokashi dust on the collect compost, wait two

weeks to a month and then bury it in your garden beds. Or, if you

have an abundance like I do, cut off the bottom of a 55 gallon drum

(skillsaw, sawzall or even a hand saw), dig a nice deep hole, and stick

the drum in about 1/3 of the depth of the drum. The top lid can

be locked or sealed with the metal ring that comes with a proper 55

gallon drum. When you've filled it to soil level, remove bin to

next spot, bury with a couple of reserved buckets of soil.

I highly recommend planting squash and corn.

A tip for city dwellers needing

to compost in limited space: I highly recommend 5 gallon pails

with gamma seal lids, bokashi dust on the collect compost, wait two

weeks to a month and then bury it in your garden beds. Or, if you

have an abundance like I do, cut off the bottom of a 55 gallon drum

(skillsaw, sawzall or even a hand saw), dig a nice deep hole, and stick

the drum in about 1/3 of the depth of the drum. The top lid can

be locked or sealed with the metal ring that comes with a proper 55

gallon drum. When you've filled it to soil level, remove bin to

next spot, bury with a couple of reserved buckets of soil.

I highly recommend planting squash and corn.

I've a tiny garden on the front

and side of my home, 8 people's worth of compost on a regular basis and

not enough space for a covered, screened compost pile as required by

city regulations. This works even in our zone 4 winters. It

costs the "input" of the bokashi mix but I see that as a fair trade-off

for composting every type of kitchen scrap produced. I pre-dig my

raised garden beds in the fall, reserve the soil in 5 gallon pails to

our porch, and fill with compost and cover over throughout the

winter. I'll plant most anything but carrots in this.

I've a tiny garden on the front

and side of my home, 8 people's worth of compost on a regular basis and

not enough space for a covered, screened compost pile as required by

city regulations. This works even in our zone 4 winters. It

costs the "input" of the bokashi mix but I see that as a fair trade-off

for composting every type of kitchen scrap produced. I pre-dig my

raised garden beds in the fall, reserve the soil in 5 gallon pails to

our porch, and fill with compost and cover over throughout the

winter. I'll plant most anything but carrots in this.

As for varmits, danged,

varmits. We have none interested in our outdoor bins. We

also are the only ones in the neighborhood without a chewed through

garbage cart. Remember, we're in the city and squirrels and

rabbits and pets are what we get the most, minus the odd opossum

(different story there). The squirrels don't smell the "food" in

our garbage anymore and we have a very clean garbage cart now.

The slickness of the bokashi system in the city versus the worm tower,

which I tried and failed with, is that it is an anaerobic process to

start and so if it stays anaerobic just a bit longer till you pull the

bin off and cover with soil, there isn't a problem with smell.

The other nice piece is it allows us to compost an enormous amount,

easily two 5 gallon pails a month, on-site, through frozen ground

winters while still meeting city code requirements.

This is not what I'd do if I

had 10 acres and no city restrictions. But for our circumstances

I'd say it's very useful and others may have similar circumstances.

Editor's

note: The author of this tip chose to remain anonymous, but you can

read more about another

homesteader's experience with bokashi here.

We've got some chorus frogs

here that sometimes get confused on warm December days like yesterday

and let out a few wimpers.

My new wild

mushroom system is to

check familiar spots on these days.

A more scientific approach

would be to monitor local soil temperatures.

Our pasture trees need a

bit more thought, but the rest of the perennials are finally mulched

down for the winter. I played around with this and that whenever

the urge struck or the materials were on hand, so the ground beneath

our trees and bushes is a hodge-podge of living cover

crops, piles

of dead autumn weeds,

two-year-old composted

wood chips, tree

leaves raked out of the woods, and deep

bedding from the chicken coops.

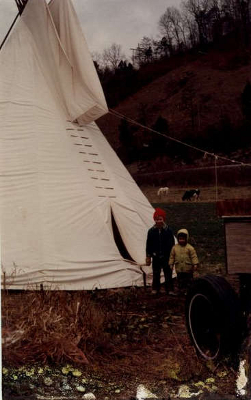

Oh, and I shouldn't forget

the logs and stumps scattered helter-skelter around the bases of my

trees and bushes. This stump in particular has a long and

illustrious history since the bulldozer that hauled in our trailer used

it as a counterweight to make sure the machine didn't tip over when

pulling our ancient mobile home up the ford.

The wood has slowly wasted away into top-notch soil in the nearly six

years since I took the shot below with our two new pets in January 2007.

Oh, and I shouldn't forget

the logs and stumps scattered helter-skelter around the bases of my

trees and bushes. This stump in particular has a long and

illustrious history since the bulldozer that hauled in our trailer used

it as a counterweight to make sure the machine didn't tip over when

pulling our ancient mobile home up the ford.

The wood has slowly wasted away into top-notch soil in the nearly six

years since I took the shot below with our two new pets in January 2007.

I'm not sure how a post

that was originally going to be about mulch longevity worked its way

around to highlighting Huckleberry, but our ultra-spoiled cat thinks

that's the way things should always be. I'll try to stay on topic

tomorrow.

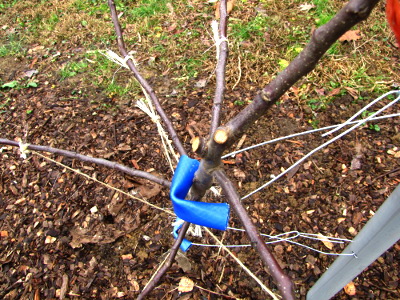

I figured out an easier way

to drill through the high

density orchard PVC

support post for attaching the guide wire.

At first I was drilling

through the metal of the fence post the PVC sits on, but about 3/4 of

the way through I discovered if you line up the smaller side of the

post with the tree trunk then you can just drill a hole through just

the PVC at the far end.

"I

was poking around your site the other day and came upon an earlier post

about your Poorman Gooseberry (and I noticed that you have a gooseberry

start to share with Sarah - along with the other perennials we in the

virtual world watched you divide on your blog and then Sarah plant on

her blog.) [Where's mine?]"

"I

was poking around your site the other day and came upon an earlier post

about your Poorman Gooseberry (and I noticed that you have a gooseberry

start to share with Sarah - along with the other perennials we in the

virtual world watched you divide on your blog and then Sarah plant on

her blog.) [Where's mine?]"--- Charity, who provided this photo of her currants, raspberries, and blackberries

I'm already trading scionwood with a couple of readers and

my three

new gooseberries for

this year have found new homes, but I thought it might be fun to help

our readers swap perennials this winter. To play along, just

follow these simple rules:

- Leave a comment with the perennials you've got extras of this

year and want to trade. I'd like to gear this toward edibles and

permaculture classics (like comfrey), but feel free to offer other

plants and scionwood. Include your wish list too, along with your

email address. (You can email

me to remove your comment once you're swapped out if don't want to

get inundated with requests.)

- Peruse other people's comments until you see someone who has what you want and needs what you have. Drop them an email and make the swap! You'll each have to pay postage, but it should even out.

- To make sure the information stays up-to-date, the swap will end

January 1.

To get the ball rolling,

here's what I've got extras of this year:

- Russian comfrey (cultivar unknown)

- Egyptian onions (bottom bulbs at this time of year)

- Caroline ever-bearing red raspberies (extremely productive, especially in the fall)

- Thornless blackberries (unknown cultivar; it's very vigorous, with huge berries, but dies back one winter in three in our zone 6 climate, so I only recommend it for the south)

And what I'm looking for:

- Scionwood from pears resistant to fireblight (especially Seckel, Dabney, Tyson, Harrow Delight, Honeysweet, Hoskins, and Luscious)

- Sal (Gene strain), Marselles vs Black, and Blue Celeste figs

- All kinds of weird permaculture plants. If you want

something I have, feel free to offer something in trade.

If the swap goes over

well, I'll try to save back some other interesting perennials next

year, like gooseberries, echinacea, chives, and figs. Maybe a

plant swap can be an annual event?

In the winter we usually

shift into a routine where we work on indoor stuff in the morning and

do outdoor activities after lunch when the sun creeps over our little

mountain.

When it's cold we usually

work on less labor intensive items, which I've noticed has an impact on

my mood if I didn't get my core body temperature raised for at least 20

minutes.

A solution that's been

working for me is an old exercise bike (Thanks Mamaw). Doing it with

sunshine seems to double the positive effect, and maybe being in the

middle of the garden adds a nice psychological boost. In the future we

want to add some sort of generator as an alternative method of charging

the solar cell batteries when we get them hooked up.

Trailersteading is entering the editing

stages this week, but I've discovered that Amazon's policies have

changed (or maybe just been tightened) so I won't be able to sell it

for 99 cents. As my regular readers know, I think a picture is

worth a thousand words, so I can't seem to talk myself into including

any fewer than 124 images in the book. But pictures make the file

larger, and that means the lowest price Amazon will allow me to set for

the book is $1.99.

Trailersteading is entering the editing

stages this week, but I've discovered that Amazon's policies have

changed (or maybe just been tightened) so I won't be able to sell it

for 99 cents. As my regular readers know, I think a picture is

worth a thousand words, so I can't seem to talk myself into including

any fewer than 124 images in the book. But pictures make the file

larger, and that means the lowest price Amazon will allow me to set for

the book is $1.99.

So I thought I'd check

with you all and ask which option you think is best:

Sell the whole book for $1.99.

I'm afraid I might lose some impulse buyers at such a "high" price,

even though this book is as long as three of my Weekend Homesteader

ebooks combined, so it would still be a good value.

Sell the whole book for $1.99.

I'm afraid I might lose some impulse buyers at such a "high" price,

even though this book is as long as three of my Weekend Homesteader

ebooks combined, so it would still be a good value.

- Break it in half and sell each

half for $0.99. I'm not as sure about breaking the book up

because it's really written to be one coherent whole. On the

other hand, I can see a reader being more willing to take a chance on

the first half for 99 cents, figuring if they hate it, they don't have

to buy the second half.

- (I know there's the option of taking out pictures, but I'm just not willing to do it.)

Other than the price issue

(and the sinking suspicion that I'm going to get a lot of bad reviews

due to trailer stigma), I'm very excited about this book. Eight

fascinating trailer-dwellers shared their experiences with great

honesty and depth, and I was intrigued to discover that even energy use

(a mobile home's biggest Achilles' heel, in my opinion) was below the

national average for every homesteader interviewed. I'm taking

the time to edit the ebook within an inch of its life, though, so you

won't hear more for a couple of weeks.

Other than the price issue

(and the sinking suspicion that I'm going to get a lot of bad reviews

due to trailer stigma), I'm very excited about this book. Eight

fascinating trailer-dwellers shared their experiences with great

honesty and depth, and I was intrigued to discover that even energy use

(a mobile home's biggest Achilles' heel, in my opinion) was below the

national average for every homesteader interviewed. I'm taking

the time to edit the ebook within an inch of its life, though, so you

won't hear more for a couple of weeks.

Meanwhile, if you want

to make my day, please consider leaving a review of Weekend

Homesteader: April (equivalent to the first month of the paperback,

with a few bonus pictures). I'm trying not to let it bother me

that half of the reviewers gave it three stars,  reminding myself that by

reaching beyond my choir, I'm bound to hit a lot more negativity.

reminding myself that by

reaching beyond my choir, I'm bound to hit a lot more negativity.

(Okay, I'll admit it,

the bad reviews are driving me nuts. I'm quite adept at figuring

all of the really nice reviews are written by people being kind while

the bad reviews are by honest people. So if you honestly liked the first chapter,

your review would cheer me up considerably.)

To thank you all for

your kind input, I'm giving away Weekend

Homesteader: September today on Amazon. Enjoy!

The exercise

bike I've been riding had one major flaw. The seat was old with

very little padding.

I was pleasantly surprised by

this Schwinn over sized seat

for 20 dollars.

A proper seat makes it easier

for me to get past that 20 minute mark and eliminates the numbness

that sometimes lingered a few minutes after some rigorous riding.

Although Mark and I are

excited about the possibilities of a high-density

apple planting,

we're also well aware of all of the disadvantages of dwarfing

rootstocks. So we're hedging our bets with three apples on M111, trained using similar methods to

those on Bud9.

In case you're not a

rootstock geek, M111 is a rootstock that makes a

semi-dwarf tree, generally reaching a spread of 14 to 20 feet, compared

to 6 to 10 feet for Bud9. I've had at least two apple growers

tell me that they manage to keep semi-dwarf trees down to the size of a

dwarf with careful pruning and training, giving them the benefits of a

more copious root system without requiring the space of a typical

semi-dwarf tree. I hope I can do the same and can include early

bearing in the list of dwarf-like properties of a miniaturized

semi-dwarf.

Reality hit when the

semi-dwarf trees showed up and required a lot more initial pruning than

the dwarf trees did. The latter had been trained in the nursery

with a high density system in mind, so they had lots of little branches

("feathers") running up and down the trunk, but the former simply had

two whorls of scaffolds a couple of feet apart. I kept the bottom

whorl (although shortening and training the branches down below

horizontal), then whacked off the top to promote new branching along

the trunk.

Reality hit when the

semi-dwarf trees showed up and required a lot more initial pruning than

the dwarf trees did. The latter had been trained in the nursery

with a high density system in mind, so they had lots of little branches

("feathers") running up and down the trunk, but the former simply had

two whorls of scaffolds a couple of feet apart. I kept the bottom

whorl (although shortening and training the branches down below

horizontal), then whacked off the top to promote new branching along

the trunk.

To keep this

semi-scientific, I sprinkled the semi-dwarfs amid the dwarfs and was

careful to include one variety that was duplicated on the two types of

rootstock. The experiment obviously won't give me scientific data

good enough to print, but should help me decipher which system works

best on our farm. I'm excited to start playing with training in

earnest once the spring growing season begins!

My Pro Line hip waders

started leaking back in the Summer and duct tape only seemed to slow

the trickle.

I want to guess the times I

used them are somewhere between 20 and 30. Feels like they should have

lasted longer.

One thought I had was to use

some epoxy and glue a piece of rubber inner tube over the hole.

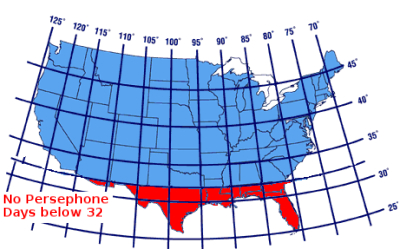

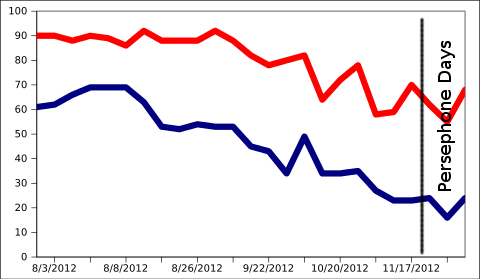

In

The

Winter Harvest Handbook, Eliot Coleman posits that

days shorter than ten hours (the Persephone

Days)

put nearly all garden plants into a state of suspended animation.

If we want to harvest greens all winter, we need to get them mature

before the Persephone Days begin and then pick a bed at a time until

the greenery starts growing again in the late winter.

In

The

Winter Harvest Handbook, Eliot Coleman posits that

days shorter than ten hours (the Persephone

Days)

put nearly all garden plants into a state of suspended animation.

If we want to harvest greens all winter, we need to get them mature

before the Persephone Days begin and then pick a bed at a time until

the greenery starts growing again in the late winter.

The trouble with this

hypothesis is that it's awfully tough (on the

farm level) to disentangle the effects of day length from the effects

of cold. Do our plants really stop growing because of the short

period of sunlight, or are they just hibernating until warm weather

comes back? Without meaning to, I did a test with my tatsoi

and tokyo bekana this fall, and it seems like these two greens

varieties, at least, are more interested in temperature than in day

length.

The Persephone Days for our

farm began on November 22, which was right

on Thanksgiving this year. I wanted to serve leafy greens for six

during our Thanksgiving dinner, so I picked the beds hard that

morning. In fact, I figured neither the tatsoi nor the tokyo

bekana would survive the winter, so I might as well cut the tender

hearts right out of them. (I usually try to let my greens

cut-and-come-again by harvesting outside or middle leaves, allowing the

tender new growth to stay put.) But when I came back around with

my scissors last week, I noticed that the harshly cropped tatsoi and

tokyo bekana were both putting out new growth.

The Persephone Days for our

farm began on November 22, which was right

on Thanksgiving this year. I wanted to serve leafy greens for six

during our Thanksgiving dinner, so I picked the beds hard that

morning. In fact, I figured neither the tatsoi nor the tokyo

bekana would survive the winter, so I might as well cut the tender

hearts right out of them. (I usually try to let my greens

cut-and-come-again by harvesting outside or middle leaves, allowing the

tender new growth to stay put.) But when I came back around with

my scissors last week, I noticed that the harshly cropped tatsoi and

tokyo bekana were both putting out new growth.

This has been an unusual

early winter because, even though day length is around 9.75 hours at

the moment, we've been

enjoying a warm spell with nights above freezing and days nearly

balmy. And our greens are taking advantage of the weather to grow

and grow.

Of course, I don't know

for sure whether these greens might not go into a

state of suspended animation at 9.5 hours or 9 hours despite the

temperature. Some days, I wish I had a research lab and crew of

grad students at my disposal to get real data, but for now, I'm busy

eating the evidence.

We recently decided it was

time to try

for a litter of rabbits.

Since that time, there have been few noticeable behavioral or physical

changes in our doe. Then...late last week, instinct has been

kicking in and the hay that we have given her has changed from a food

source to a source of material for constructing a nursery inside of her

house/nesting

box. Last week

when Dawn noticed the change in behavior, she quickly grabbed the

camera to catch some photos of her constructing her nest. It's

actually quite interesting to watch. She will sort through the

hay using her mouth, then once she has a bundle she is happy with, she

will shake and rub it side to side with her head. Then, with a

suitable bundle secured, off she goes into the house with her next

batch.

Dawn has read that the doe

should also pull fur from her coat to line the nest with some warm

material. It is said that she should begin doing this at any time

in the week before the litter arrives, though our doe has not begun

doing this yet. We've also noticed that she has shaped a

depression in the hay which is sort of like a bird nest visible in one

of the photos below. We're guessing that this is where she plans

to deliver? Unless it is just a random placement of hay that

we're reading too much into.

We're presently debating if

it will be cold enough that we need to make some accommodations to keep

the kits warm. We just had a cold front pass through today and

our usually mild winter weather has taken a bit of a chilly turn.

We may put up some clear tarp and a heat source if we think it becomes

warranted.

We had hoped that by the

time of this post we would have photos of some kits and stories of how

the doe and kits were doing. However, I guess mother nature has

decided that will have to wait till next time. For now, here are

a couple more photographs.

Shannon and Dawn

will be sharing their experiences with raising meat rabbits on Tuesday

afternoons. They homestead on three acres in Louisiana when time off

from life and working as a sys admin permits.

Thank you Brent for your

comment the other day asking about the results of our experiment to use

home

grown mushroom spawn to

inoculate a magnolia

stump.

It took me till today to go

check. One in the back was a little past being fresh enough to cook,

but the one in the front is almost perfect.

These kinds of results make

me wonder if we shouldn't think about inoculating more stumps.

One of the ideas I got

out of The

Holistic Orchard was

applying

gypsum to improve drainage in the heavy clay parts of our garden. As you can see from

the first photograph in this post, a day or two of rain in the winter

is all it takes to saturate our soil and create puddles here, there,

and everywhere. Gypsum is reputed to increase drainage and boost

calcium levels (which many people believe results in healthier, more

nutritious plants) without sweetening the soil, so I decided to give it

a try.

When

amending soil, it's generally a good idea to perform a soil

test first, then

calculate how much of the amendment you really need. In many

cases, adding too much is worse than adding none at all, so I was leery

when one

of our readers recommended: "Be very liberal also. It

doesn't burn at all. Also you can used it often."

When

amending soil, it's generally a good idea to perform a soil

test first, then

calculate how much of the amendment you really need. In many

cases, adding too much is worse than adding none at all, so I was leery

when one

of our readers recommended: "Be very liberal also. It

doesn't burn at all. Also you can used it often."

However, a bit of

research proved him right. One of Clemson

University's soil scientists wrote, "There are no easily accessible

guidelines regarding the application rate of gypsum in a homeowner

situation. It is sparingly soluble and so it is nearly

impossible to over-apply."

I've seen recommendations as high as 2,000 pounds per acre, which is a lot

of gypsum.

In the end, I opted to

just sprinkle the pellets across wet soil the way I would if seeding a

cover crop, so the first fifty-pound bag covered perhaps a quarter of

the forest garden. The feed store has another 450 pounds waiting

for us, so we'll be spreading that slowly but surely as our car and

golf cart are up to the hauling. Most websites recommend

repeating the application annually for three years, at the end of

which, hopefully, our winter puddles will be less problematic.

The green revolution, peak

oil, sustainable building, and water stewardship formed the themes for

this week's selection of Folks,

This Ain't Normal.

I found the first to be the most interesting, with Salatin's history of

chemical fertilizers stemming from war-era scientific advances butting

up against Sir Albert Howard's studies of composting in India using

cheap manpower. If you're only going to read one chapter for

ideas and book recommendations, "The Poop, The Whole Poop, and Nothing

But the Poop" would be my top choice so far.

The green revolution, peak

oil, sustainable building, and water stewardship formed the themes for

this week's selection of Folks,

This Ain't Normal.

I found the first to be the most interesting, with Salatin's history of

chemical fertilizers stemming from war-era scientific advances butting

up against Sir Albert Howard's studies of composting in India using

cheap manpower. If you're only going to read one chapter for

ideas and book recommendations, "The Poop, The Whole Poop, and Nothing

But the Poop" would be my top choice so far.

The other chapters suffered

more from Salatin's general inability to stay on topic and from his

wish to alienate everybody at least once during each essay. But I

did find his theories on both energy and water stewardship fascinating

--- Salatin posited that if we were personally involved in acquiring

energy and water and if systems were designed on small, local scales,

we'd have healthier environments and better societies.

The other chapters suffered

more from Salatin's general inability to stay on topic and from his

wish to alienate everybody at least once during each essay. But I

did find his theories on both energy and water stewardship fascinating

--- Salatin posited that if we were personally involved in acquiring

energy and water and if systems were designed on small, local scales,

we'd have healthier environments and better societies.

What jumped out at you

in this week's chapters? Feel free to head back to the first and second weeks' selections to comment

as well if your book recently showed up. And don't forget to read

chapters 14, 15, and 16 (up through "Scientific Mythology") for next

Wednesday. Thanks for reading along!

We had a problem this year

with the chickens scratching away precious mulch from our young Mulberry tree.

I'm not sure if these walls

will be tall enough, but as I'm looking at the picture it occurs to me

that an easy way to get a few more inches might be to put a chimney

brick under each corner.

The harshness of

mid-November took its toll and our beautifully yellow-green beds of oilseed

radishes are dying

back early this year.

It's fascinating to see which

plants succumb first. The ones on the shaded, north sides of beds

in the least-sun-exposed front garden turned slimey over a week ago,

followed by overmature plants and overcrowded young plants

elsewhere. In stark contrast, the pasture

of oilseed radishes,

although it grew slowly in the partial shade during the fall, is still

looking vibrantly green due to the

mitigating effects of the trees overhead.

It's fascinating to see which

plants succumb first. The ones on the shaded, north sides of beds

in the least-sun-exposed front garden turned slimey over a week ago,

followed by overmature plants and overcrowded young plants

elsewhere. In stark contrast, the pasture

of oilseed radishes,

although it grew slowly in the partial shade during the fall, is still

looking vibrantly green due to the

mitigating effects of the trees overhead.

For comparison's sake,

we didn't see our

radishes decline

like this until January last year. That means we're probably

getting less biomass bang for our seed buck this year, and will need to

lay down a mulch to keep winter weeds at bay before long. But I

think the oilseeds still paid for themselves even with the shorter

growing cycle.

It

got down to 21 degrees last night, which prompted the Thermo Cube to turn on and use

.04 kilowatt hours of energy.

We've had some serious rain

this week, but no problems with the piled up dirt being eroded.

Makes me wonder if the mobile

home dirt anchors were over kill? Maybe just tilting the whole

thing back on an angle is enough to prevent a wash out?

"What determines when to pick

a ripe mushroom? I've noticed you seem to have an eye for knowing

when they are just right or beyond good eating. So what are your

cues?"

"What determines when to pick

a ripe mushroom? I've noticed you seem to have an eye for knowing

when they are just right or beyond good eating. So what are your

cues?"

With oyster

mushrooms and shiitakes (the ones we know best), the

fruiting bodies are tastiest when they're just shy of totally

mature. That means they've expanded out to full size, but the cap

is still curling under just a little at the edges.

A day or so after reaching

this point, mushrooms are overmature and not nearly as tasty.

Then, the caps are flat at the edges, and the gills underneath have

often started to be gnawed away by insects.

A day or so after reaching

this point, mushrooms are overmature and not nearly as tasty.

Then, the caps are flat at the edges, and the gills underneath have

often started to be gnawed away by insects.

(I don't mind a few

insects in a good mushroom --- just tap the cap lightly against your

palm and the little black beetles will fall out. Any left behind

are bonus protein.)

You can pick mushrooms

too young and they're still quite tasty, but you get much less mass

since the caps haven't expanded yet. I do this often if a really

cold spell is coming,  since I figure the mushrooms

will be past their prime by the time warm temperatures tempt them to

expand.

since I figure the mushrooms

will be past their prime by the time warm temperatures tempt them to

expand.

Noticing mushrooms at

peak ripeness has been the entirety of our cultivation effort this

year. There seem to be wild and semi-wild (we inoculated them,

then ignored them) mushroom stumps, logs, and trees all over the farm

now, which makes it easy to pluck mushrooms whenever they appear.

The ones that get away spread spores to inoculate nearby logs and

trees, and the cycle continues. If you live in a damp climate,

it's hard to beat this mushroom-growing method in terms of calorie per

hour!

Our new Rhode

Island Red hens have been a good addition to the flock.

They seem to get along fine

with the rooster, but the other hens have been giving them the cold

shoulder.

Most of the time they're on

the roost with everybody else, just scooted over to the far end with a

gap between, but the other night I noticed they were huddling in the

corner.

That's why I installed yet another roosting station on the other end of

the coop. Maybe giving the original hens some space at night will help

to improve our flock dynamics?

One of my pet peeves about

the permaculture world is that we all read the same books and then we

regurgitate the information. After you see the same idea in print

five times, you assume it works...even if no one's really tried it.

One of my pet peeves about

the permaculture world is that we all read the same books and then we

regurgitate the information. After you see the same idea in print

five times, you assume it works...even if no one's really tried it.

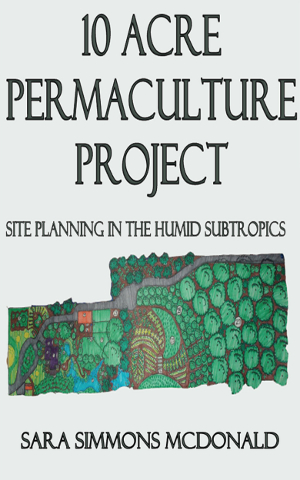

Sara McDonald's A

10-Acre Permaculture Project: Site planning in the humid subtropics begins to fill that

gap. This design plan presents several good ideas for working

around a high water table and producing an interwined permaculture

farm. I particularly enjoyed the beautifully drawn diagrams and

the year-by-year implementation information --- I could have saved a

lot of money and heartache if I'd planted my garden in cover crops for

soil building from year one and waited to plant fruit trees until year

three.

Of course, what I really

want to see is before and after photos taken every year for the next

decade with information on which parts succeeded and failed --- I'll

look forward to buying that followup ebook in 2021. In the

meantime, I hope other non-big-name permaculture practitioners will

self-publish their own plans and followups. I promise, it's very

easy to put an ebook up on Amazon, and if you tell me about your plan,

I'll buy it and review it.

Jack

Spirko was kind enough to have me on his

Survival Podcast recently where we talked about deer deterrents,

chickens, and using a blog to promote a personal micro business.

Jack

Spirko was kind enough to have me on his

Survival Podcast recently where we talked about deer deterrents,

chickens, and using a blog to promote a personal micro business.

I really enjoyed an episode

he did this year with fruit expert Dr

Lee Reich. Jack has a natural way of making his guests feel welcome

while packing in some valuable information.

Scenes in The

Hobbit aside,

thrushes are usually shy, so I was surprised when this Hermit Thrush

showed up in the yard Friday afternoon. Actually, I had forgotten

that we had a  resident winter thrush, so I

was a bit concerned that the bird might have missed the boat on fall

migration. I looked up possible thrush foods, discovering that

insects are preferred but fruits are common in fall and winter, then

scattered raisins around the yard in case the thrush was starving.

resident winter thrush, so I

was a bit concerned that the bird might have missed the boat on fall

migration. I looked up possible thrush foods, discovering that

insects are preferred but fruits are common in fall and winter, then

scattered raisins around the yard in case the thrush was starving.

Our thrush didn't seem

interested in my raisins, but it did spend half an hour hopping around

and pecking at our damp earth, presumably finding worms and

insects. How magical is it to have a Hermit Thrush taking the

place of a suburban Robin, wandering around the yard?

The sad day finally came

--- yurt removal time. My brother Joey bought

the yurt in 2008

when he was living in the city and pondering purchasing land. He

figured he could use it as a retreat on our property whenever he

wanted, then move it to his new land. Mark and I loved having a

visitor who was willing to retreat to his own personal space once our

socializing powers ran out, so we were thrilled when Joey added

a wood stove to made

yurt camping fun even in cold weather.

After a couple of years

of joyous yurt visits, though, Joey started renting an underground

house way out in the

country, which fulfilled his yearnings and left the yurt vacant.

We still managed to tempt him over to visit with homegrown meals, but

he returned to his cozy woodland dwelling for the nights.

Meanwhile, weather (and

mice) were taking their toll on the yurt. This summer, the

natural canvas fabric making up the roof developed some pretty big

leaks, and the rodents began gnawing at the wooden supports. Joey

figured it was time to take the yurt down while it was still useable

(which hopefully it will be if the roof is replaced).

I asked Joey if he'd go

the yurt route again, and he said "Definitely!" Although the

structure wasn't cheap, we put it up in an afternoon and it served him

well for quite a few years.

Although I'm sad to see

the yurt go, I have to admit that it didn't make the perfect guest

cottage I'd hoped for. After tromping through the mud to get to

our trailer, I never was able to talk a single guest (except Joey) into

walking another city block through the woods (no mud, though!) to enjoy

our yurt accomodations. Instead, our nearby

intentional community

seems to be the perfect spot to house visitors, complete with modern

conveniences.

Farewell, sweet

yurt! May you rise again elsewhere soon.

One of our winter projects we

started recently is trying to make one of the chicken pasture hillsides

more functional by experimenting with a terrace

system.

The chickens do okay with the

slope, but a few flat places will make it easier for us to cultivate

things like Mulberry

trees and Nanking

cherry bushes.

It should make it easier for

us to control the weeds as well, which I've noticed can get thick

enough to stop most chickens from pushing through.

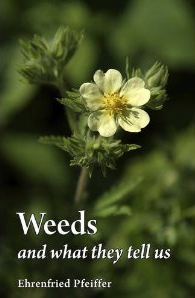

Weeds

and What They Tell Us

is a newly-released, lightly-edited version of Ehrenfried Pfeiffer's

book of nearly the same name (without the "Us") from 1970.

Unfortunately, this little book didn't live up to its promise,

especially given the high price of $13 for a 90 page text. I

could ignore the typographical errors, but the arguments are scattered

and somewhat contradictory.

Weeds

and What They Tell Us

is a newly-released, lightly-edited version of Ehrenfried Pfeiffer's

book of nearly the same name (without the "Us") from 1970.

Unfortunately, this little book didn't live up to its promise,

especially given the high price of $13 for a 90 page text. I

could ignore the typographical errors, but the arguments are scattered

and somewhat contradictory.

The intriguing part of

the book is pretty much covered by the title. Pfeiffer believed

that the particular weeds found on our farms are signs of improper

management: "Weeds are indicators of our failure." A single plant

doesn't tell us much, but a suite of plants in the same category or an

increase in numbers of a certain plant is a sign of one of three big

problems:

- Acidic soil (often linked to

poor drainage) --- sorrels, docks, fingerleaf weeds, lady's

thumb, horsetail, hawkweed, and knapweed

- Crusted soil and/or hardpan

--- field mustard, horse nettle, penny cress, morning glory,

quackgrass, chamomile, and pineapple weed

- Overcultivated soil,

excessively loose without much organic matter --- lamb's

quarter, plantain, chickweed, buttercup, dandelion, nettle, prostrate

knotweed, prickly lettuce, field speedwell, rough pigweed, common

horehound, celandine, mallow, carpetweed, and thistles

The trouble is that I'm

not sure Pfeiffer's categories entirely work, especially since later

sections of the book suggest certain plants are indicators of other

soil problems. I'm also not a fan of his solutions to weed

problems, which seem to consist of lots and lots of tilling and some

chemicals (along with less problematic but rather obvious techniques

like hand weeding, mowing when flowers are just pollinated, draining

wet ground, planting cover crops, and adding compost and lime if

needed).

In the end, I'm still

waiting for a good book on this topic, so if anyone wants to go out and

observe weeds, I think your treatise would be well-received.

Meanwhile, for the rest of you, I recommend checking this book out of

your library (or just reading my summary above, which hits the

highlights).

These fence posts are now

sunk over 4 feet in the ground.

Will it be enough to hold

back the hill from wanting to smooth out?

If it holds for just a few

years we might have enough cultivated plants with deep roots by then

that will lend a hand in keeping the terrace

in place.

I

wrote in July that I

was going to repot our seedling American persimmons this winter, let

them grow another year, graft Asian persimmon tops to them the

following year, and finally plant them out the year after that.

However, I got to thinking that my original method would be a lot of

time in a pot and multiple transplantings for a species that

has personal space issues surrounding its roots, so I decided to change

gears.

Another factor to consider is

winter hardiness. I want to graft Asian

persimmons onto my

American persimmon rootstocks because many varieties of the former are

naturally dwarfing (so they can go under the powerline) and since I've

heard the flavor can be better than wild persimmons. But Asian

persimmons are only moderately winter hardy here in zone six.

Many people push the envelope by letting the American persimmon

rootstock grow four feet tall before grafting on the Asian persimmon,

figuring that the coldest air will be right near the ground where the

hardier native persimmon can handle it, and I plan to follow suit.

Another factor to consider is

winter hardiness. I want to graft Asian

persimmons onto my

American persimmon rootstocks because many varieties of the former are

naturally dwarfing (so they can go under the powerline) and since I've

heard the flavor can be better than wild persimmons. But Asian

persimmons are only moderately winter hardy here in zone six.

Many people push the envelope by letting the American persimmon

rootstock grow four feet tall before grafting on the Asian persimmon,

figuring that the coldest air will be right near the ground where the

hardier native persimmon can handle it, and I plan to follow suit.

Which is all a long way

of explaining why I planted ten little persimmon seedlings into various

chicken

pastures over the last few weeks. I'm glad I did --- the

persimmons had developed a remarkable amount of root growth during

their first growing season, with many roots already running around the

bottoms of the pots. If I try this again, I should probably plant

one seed per container into small but deep pots, but hopefully my

seedlings will forgive me for the one root-mangling episode.

Now I just need to give

the seedlings a little love as they overcome the trauma of

transplanting, and wait for them to get tall enough to graft on Asian

persimmon scionwood. We're highly unlikely to see any fruits

before 2018 (with 2021 more likely), but the sooner we start, the

sooner we eat.

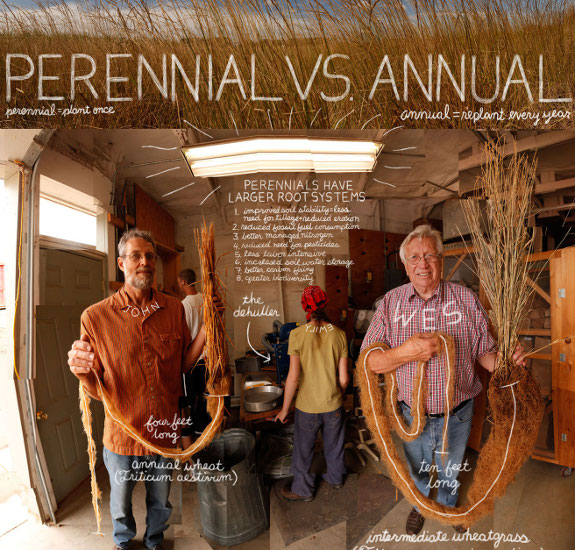

Two of the three chapters we

read this week in Folks,

This Ain't Normal

focused on our modern, grain-based, livestock-farming system, so I

thought that would be a good topic for this week's discussion.

Salatin explained that before modern machinery made harvesting and

processing grain a breeze, wheat, rye, barley, and oats required too

much labor to be fed to livestock. This was a good thing because,

in areas where grain production wasn't used sparingly, deserts soon

began to encroach on farmland.

Two of the three chapters we

read this week in Folks,

This Ain't Normal

focused on our modern, grain-based, livestock-farming system, so I

thought that would be a good topic for this week's discussion.

Salatin explained that before modern machinery made harvesting and

processing grain a breeze, wheat, rye, barley, and oats required too

much labor to be fed to livestock. This was a good thing because,

in areas where grain production wasn't used sparingly, deserts soon

began to encroach on farmland.

Then tractors and

combines came along, providing cheap tillage and processing, while

chemical fertilizers allowed us to grow massive amounts of grains

without closing the ecosystem loop with enough animals to feed the

soil. Add in cheap fuel to transport those now-copious grains,

and we saw another sea shift in agriculture --- meat and dairy animals

were crammed into CAFOs where they were fed grains and where their

concentrated manure became a waste product instead of a sought-after

source of fertility. Animal cruelty and meat quality aside, the

system is clearly broken from a purely biological perspective.

Salatin asserts that there is

a better way. Herbivorous meat animals (cows, sheep, and goats)

can be raised entirely on pasture, which when managed correctly can

heal soil that is otherwise valueless for agriculture. If we kept

our animals on pasture, we'd only have to grow grains for people, and

there are a couple of very sustainable approaches to grain production

to choose between. Colin Seis, an Australian experimental

farmer, has developed a system of growing grains without tilling within

a traditional pasture, with each plot of land producing grains one year

in five. Meanwhile, Wes Jackson is developing perennial

grains that only require the ground to be tilled and planted once or

twice a decade.

Salatin asserts that there is

a better way. Herbivorous meat animals (cows, sheep, and goats)

can be raised entirely on pasture, which when managed correctly can

heal soil that is otherwise valueless for agriculture. If we kept

our animals on pasture, we'd only have to grow grains for people, and

there are a couple of very sustainable approaches to grain production

to choose between. Colin Seis, an Australian experimental

farmer, has developed a system of growing grains without tilling within

a traditional pasture, with each plot of land producing grains one year

in five. Meanwhile, Wes Jackson is developing perennial

grains that only require the ground to be tilled and planted once or

twice a decade.

Although Salatin doesn't

mention this, the obvious question is --- can these systems be tweaked

so the food is affordable for folks who aren't wealthy? My answer

to this biological-farming question (which is also raised about

permaculture and organic gardening) is: "Who cares how much ethical

food costs? Grow your own and it's cheaper than the mainstream

stuff in the grocery store, which really costs a lot more than you

think if you add in the environmental side effects." But it is

true that cows are a lot harder to fit into a backyard than

zucchinis. What do you think?

We're skipping next week (since I'll be regaling you with a lunchtime series about trailer dwellers), then we'll discuss chapters

17 through 19 on January 2. If you're just tuning in, you might

want to check out part

1, part 2, and part

3 of the book club

discussion. Thanks for reading along!

When we tested our soil

last winter, my

analysis was pretty

simple. I just wanted to make sure there weren't problematic

heavy metals in the soil and that all of the useful nutrients were

available in sufficient amounts. Everything looked okay, so I

didn't make any special changes after viewing my results.

Now

that I'm reading Steve Solomon's excellent book The

Intelligent Gardener,

though, I'm ready to move to a second tier of soil analysis. I

started considering the

ratios of soil nutrients last winter, but hadn't read enough on the

topic to know exactly what I was looking for and how important slight

variations from optimal percentages were. Solomon's book has sold

me on the idea that these ratios are important (more on that when I

write a lunchtime series about The

Intelligent Gardener), and that adding amendments

like gypsum to get those ratios back on

track can produce huge changes in soil characteristics.

Now

that I'm reading Steve Solomon's excellent book The

Intelligent Gardener,

though, I'm ready to move to a second tier of soil analysis. I

started considering the

ratios of soil nutrients last winter, but hadn't read enough on the

topic to know exactly what I was looking for and how important slight

variations from optimal percentages were. Solomon's book has sold

me on the idea that these ratios are important (more on that when I

write a lunchtime series about The

Intelligent Gardener), and that adding amendments

like gypsum to get those ratios back on

track can produce huge changes in soil characteristics.

The only trouble is that

the information in Solomon's book only works if you use data from a

Mehlich 3 soil analysis. Any kind of soil test will give you

useful results, but you can't necessarily compare results between

different types of tests, and UMass

Amherst, who tested

my soil last year, uses a modified Morgan extractant.

Which is all a long way

of explaining why I'm biting the bullet and testing again, this time

using Logan Labs, which is explicitly

recommended by Solomon. If you want to follow along, I recommend

you learn about the basics of soil testing in Weekend

Homesteader: January,

then get your soil samples in the mail now. I'll be analyzing my

results here in early January (or whenever I finish digesting Solomon's

book), and will be glad to help you do the same.

Anna's calf-high Bogs have been leaking for a little

while now.

I cut out a small piece of

inner tube and tried to seal it over the troubled area with a product

called Seam Grip. It's

clamped down and needs to dry over night.

It took over half the tube to

do the left boot, so I used a cheaper adhesive called Welder on the right side which cost a

fraction of the 18 dollar retail price of Seam Grip.

Part of the reason I

thought it was worthwhile to put a lot of effort into terracing

the powerline pasture

is completely unrelated to chickens and instead has to do with

water. The forest garden turns into a swamp during wet weather,

and while I've blamed the excess water on everything from barn roof

overflow to compacted clay soil, I'm willing to entertain the notion

that the powerline cut has something to do with it as well. After

all, wet weather springs pop up at the base of that hillside during

winter rains, suggesting that the lack of vegetation resulting from

cutting trees along the powerline has sped up flow of water, resulting

in a glut down below.

In her new ebook, One

Acre Homestead, Sara

McDonald writes about slowing the flow of energy through a system: "The

flow must be maintained, but catching and storing energy for beneficial

purposes is encouraged." In other words, one solution to my

problem would be to keep water on the hillside longer, where it can

hydrate plants and be transpired out through their leaves rather than

flooding the forest garden below. Many permaculture practitioners

use ponds to slow the flow of water, but I want to keep things simpler

by soaking up excess water with humus.

A trip into the nearby

woods turned up plenty of punky sticks and logs already rotting into

the ground. I used the drop test to determine which ones were

ready to move to the powerline cut --- if the wood broke into small

enough pieces to haul when thumped on the ground, I figured it was

ready. Six trips later, the terraces were looking a little less

barren and I was worn out.

I'll probably add more

wood later, since this is just the bare minimum needed to hold

unvegetated soil in place, but even this little bit should help.

In the immediate future, the logs will force water to pool behind them

during heavy rains, tempting more liquid to soak into the earth rather

than running off, and soon the wood will have rotted enough to suck up

rain and release it slowly during droughts. The wild fungi that

came along for the ride can't hurt either.

We enjoyed a solstice

snow, which gave me some solid (if non-numerical) data about the value

of the newly

insulated roof.

Mark and I both seem to recall that during previous snows, the frozen

water melted right off in short order, but this time around, it seems

to be sticking and staying. R30 on top of the R13 already in the

roof of the old trailer seems to be doing the trick of keeping heat

inside the house where it belongs.

To read more about

insulating a mobile home, check out Trailersteading, which I'll be writing much

more about next week.

I

wasn't sure this new

roosting option was being used until I snapped this image a few

nights ago with the flash.

I

wasn't sure this new

roosting option was being used until I snapped this image a few

nights ago with the flash.

5 feet off the ground seems

to be that sweet spot where the hens feel safe, yet still be reached

with an easy jump and a few flaps.

My

favorite part of Sara McDonald's One

Acre Homestead was

the idea of

growing our own mulch by planting a small pine plantation. Sara

notes that a 10-year-old pine forest can produce 125 to 200 bales of

needles per acre, with each bale covering 120 square feet (and with

yields increasing as the trees mature further). You should give

the trees two years off between mulch-gathering, though, so I estimate

my blueberry patch would need the mulch from about 0.3 acres filled

with 21 white pines.

My

favorite part of Sara McDonald's One

Acre Homestead was

the idea of

growing our own mulch by planting a small pine plantation. Sara

notes that a 10-year-old pine forest can produce 125 to 200 bales of

needles per acre, with each bale covering 120 square feet (and with

yields increasing as the trees mature further). You should give

the trees two years off between mulch-gathering, though, so I estimate

my blueberry patch would need the mulch from about 0.3 acres filled

with 21 white pines.

For the last six years, Mark

and I have been focusing on what

permaculture practitioners refer to as zones 1 and 2 and what I call

our "core homestead," which covers a bit over one acre. I do

have visions for forest pastures ringing our core

homestead...eventually...and I could see a pine pasture doing

double duty as mulch producer and shady summer chicken pasture.

On the other hand, we've still got areas within our core homestead that

haven't quite been reclaimed from the weeds and turned into productive

growing space, and those areas always come first.

For the last six years, Mark

and I have been focusing on what

permaculture practitioners refer to as zones 1 and 2 and what I call

our "core homestead," which covers a bit over one acre. I do

have visions for forest pastures ringing our core

homestead...eventually...and I could see a pine pasture doing

double duty as mulch producer and shady summer chicken pasture.

On the other hand, we've still got areas within our core homestead that

haven't quite been reclaimed from the weeds and turned into productive

growing space, and those areas always come first.

Still, I'll be adding

the pine tree idea to other options I've tossed around for growing our

own mulch. Oats

as a fall cover crop

work well for the beds they're planted on and chop-'n-drop species are possibilities in

the forest garden. Meanwhile, I'll just keep raking

leaves out of the woods, flagging down the wood chip guys whenever I see them,

and buying straw. What's your favorite

way to complete the loop with farm-grown mulch?

We had a strange problem with

the Toyota this morning.

The doors opened okay, but

something froze that prevented the passenger side back door from

latching shut.

One option we considered was

to wait and see if warming the car up would fix it, but time was an

issue and I felt like this is the exact sort of problem ratchet

straps were invented for.

After

getting the car

door ratchet-strapped shut, we headed on down the road

Sunday for my first (and probably only) book signing. Daddy's

partner bought two copies of my

book as Christmas

presents for family members, and Mark commemorated the occasion with

copious photos.

After

getting the car

door ratchet-strapped shut, we headed on down the road

Sunday for my first (and probably only) book signing. Daddy's

partner bought two copies of my

book as Christmas

presents for family members, and Mark commemorated the occasion with

copious photos.

I hope you're taking the

solstice season slow, uncommercialized, but full of family and friends

like we are. Happy major winter holiday of your choice!

Trailersteading:

Voluntary Simplicity in a Mobile Home is now ready to go on

Amazon! It's my favorite ebook so far, full of stories, facts,

and (hopefully) inspiration. Here's the blurb:

Trailersteading:

Voluntary Simplicity in a Mobile Home is now ready to go on

Amazon! It's my favorite ebook so far, full of stories, facts,

and (hopefully) inspiration. Here's the blurb:

Imagine what you could do with your time if you didn't have to spend $16,000 a year on rent or a mortgage. Old single-wide mobile homes can often be found for free (and installed for a couple of thousand dollars) in rural areas, so trailersteading is akin to dumpster-diving. A trailer allows you to live without debt, to keep your ecological footprint to a minimum with energy bills at or below the national average, and even to blend right in with traditional-house dwellers after a few years.

Trailersteading profiles nine mobile-home dwellers who have used trailers as a stepping stone toward achieving their dreams. Some have spent the cash they saved by renovating their trailer on extra insulation, pitched roofs, classy interiors, and even basements, while the found money has allowed others to go off the grid. Many also took advantage of the low-cost housing option to pursue their passions, becoming full-time homemakers or homesteaders.

In addition to the case studies, the book presents easy methods of minimizing the negative sides of trailer life and accentuating the positive. For example, did you know a single-wide is easy to retrofit for passive solar heating? That a simple plant-filled trellis can break up the blockiness of the trailer's external appearance? Learn which parts of installing and upgrading your trailer are easy for a DIYer and which parts should be left to the experts, along with how to cheaply heat and cool a mobile home.

128 photos and diagrams.

The rest of this week's

lunchtime series is going to sum up the lives

of four of the trailer dwellers we interviewed. To read the rest,

you'll need to splurge

$1.99 cents on the ebook (which can

be read on

nearly any device),

or wait until Friday when I'm setting the price to

free so that my loyal readers can pick up a copy without paying.

Those of you who prefer a pdf copy can email me Friday as well and I'll

send your free copy that way instead. Thanks for reading (and

double thanks if you find the time to leave a review on Amazon).

I hope you enjoy this jaunt into simple living as much as I do!

| This post is part of our Trailersteading lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I think I remember Jimmy

Carter being president when my Mamaw got the exercise bike on the left

from Sears. Its held up

nicely over the years and still offers up a good work out, but I wanted

a bike with a heavy flywheel for a future pedal power project.

The current plan is to try to

mount a low RPM generator with a rubber wheel that snugs up against the

flywheel.

Mark suggested I write a

short ebook summing up our refrigerator root cellar experiment, and I

thought it sounded like a fun idea. After all, our

youtube video on the

subject has had over 72,000 views, and we've learned a lot since making

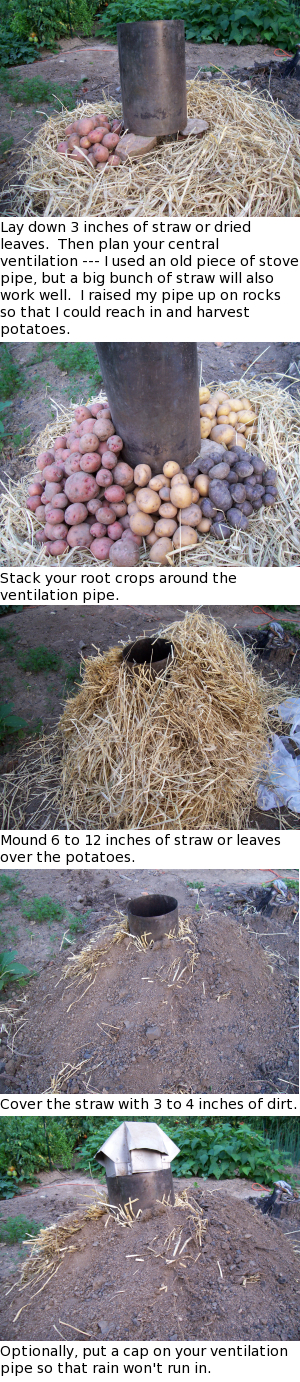

it. Granted, a few commenters were less keen on the idea ("omg