archives for 11/2012

With

lots of help from Sarah, the monthly ebook versions

of Weekend Homesteader are now available in their

revised format on Amazon!

With

lots of help from Sarah, the monthly ebook versions

of Weekend Homesteader are now available in their

revised format on Amazon!

(As a side note, Sarah

is the Bradley

of the digital world, and she works long distance.

Having just quit her job, she's available if you've got photography,

editting, or formatting work you'd like done. I'm a bit afraid to

tell you how awesome she is since she might get too busy for us

just like Bradley did. Sarah cleaned up my ebooks in ways I

didn't even know to ask for, and she might even work for Silver Fox rabbits

and Chocolate Turkeys....)

If you've been waiting

to get the revised ebooks, now's your chance to snap up all

twelve. Meanwhile,

if you've bought some or all of the ebooks in the past, you should be

getting an email from Amazon within the next month or so asking if you

want a free update to the revised editions --- say yes. We moved

things around and revised each chapter to match the paperback, plus I couldn't help adding

in more photos that didn't fit into the print version. I've also

created the twelfth month --- Weekend

Homesteader: April

--- so you have access to every project that's in the print book.

If you've been waiting

to get the revised ebooks, now's your chance to snap up all

twelve. Meanwhile,

if you've bought some or all of the ebooks in the past, you should be

getting an email from Amazon within the next month or so asking if you

want a free update to the revised editions --- say yes. We moved

things around and revised each chapter to match the paperback, plus I couldn't help adding

in more photos that didn't fit into the print version. I've also

created the twelfth month --- Weekend

Homesteader: April

--- so you have access to every project that's in the print book.

And as a final side

note, my publicist has been having me churn out guest posts right and

left to increase the buzz during the upcoming paperback launch.

You can read two of my favorites here:

Links to the monthly

ebooks are below. Thanks for reading!

This post is to remind me

next year at this time to check our mushroom logs.

These Shitake

mushrooms would've been yummy last week.

Maybe a daily chart of soil

temperatures would provide some insight into predicting when a Shitake

log might be ready to pop some fruit out?

October did turn out to

be the

month of the broccoli.

Every day or so, we'd have a huge helping and eat every sprig and chunk

--- nothing tastes better than homegrown broccoli in season.

In the spring, I cut my

broccoli heads low, peel off the woody skin near the stalk base, and

cook up the whole kit and caboodle. In the winter, though, I

don't have anything else  begging to fill the broccoli

space, so I cut the heads high, leaving most of the stem behind.

Within a week or two, side shoots come popping up, which I cut and eat

just like the original head.

begging to fill the broccoli

space, so I cut the heads high, leaving most of the stem behind.

Within a week or two, side shoots come popping up, which I cut and eat

just like the original head.

This endless broccoli

crop continues until the first killing frost --- and since we've dodged

even a light frost so far this fall, that might be a while! The

lack of frost means we're still eating raspberries too, and they're

even better in cool weather. Dare I suggest we may still be

enjoying fresh berries at Thanksgiving?

Forgetting about mushroom

logs yesterday helped me to remember that the weed eater and mower

will like me better in the Spring if I don't let fuel sit in the tank

all winter.

With any luck this post will

help me to not forget next year.

I

don't know if the distinction is variety or age, but Celeste went dormant over a week

ago, while Chicago

Hardy is still in

the act of losing his leaves. I figured I'd go ahead and protect

our fig youngster just in case cold weather comes calling before our

elder fig is ready.

I

don't know if the distinction is variety or age, but Celeste went dormant over a week

ago, while Chicago

Hardy is still in

the act of losing his leaves. I figured I'd go ahead and protect

our fig youngster just in case cold weather comes calling before our

elder fig is ready.

Since I read up a bit on

fig

cold protection,

I've decided to tweak my technique a bit. I started out by tying

the stems on the young fig tree together so they'll stay in the center

of my insulation, then I stuffed a cat food bag with freshly raked

autumn leaves.

Mashing the leaves a bit

opened up a hole in the center, which let me drop the leaf-filled bag

on top of the little fig tree.

I tied the bag at the

base to hold it in place and used the rest of my leaves to mulch the

bed heavily.

I'll keep my eye on

Celeste to see if the bag starts to come loose --- I was tempted to

push in a metal fence post to tie the bag to, but figured I might not

need it. I'm hopeful this method will work better than my previous

one since the cat

food bag should keep the leaves dry and in place. We won't know

for sure until May!

Our neighbors made this

hardware wire corn crib to keep raccoons and other critters out.

Last year was the first test

and it yielded not one kernel.

After it dries a bit more

they usually take it somewhere that grinds it into corn meal.

I've been curious about Brett Markham's Mini

Farming: Self-Sufficiency on 1/4 Acre mostly because it's been

topping the charts in Amazon's Sustainable Living category for about a

year (or more). Mini

Farming is

another one of those beginner gardening books (with the bonus of a

section on chickens and one on preserving), and I'd probably recommend

it to new gardeners before I'd send them to Square

Foot Gardening.

I've been curious about Brett Markham's Mini

Farming: Self-Sufficiency on 1/4 Acre mostly because it's been

topping the charts in Amazon's Sustainable Living category for about a

year (or more). Mini

Farming is

another one of those beginner gardening books (with the bonus of a

section on chickens and one on preserving), and I'd probably recommend

it to new gardeners before I'd send them to Square

Foot Gardening.

I appreciated Markham's

focus on economics and the inclusion of information on composting and

cover crops. On the other hand, I wasn't so keen on his Solomon-like

seed meal fertilizers

and had to stop reading for two weeks when I butted up against his

nutrition chapter. (Chapter summary: Potatoes are a vegetable, so

look how little space it takes to grow your own!)

In general, I think

Markham is one of those farmers who toes the organic line but doesn't

spend enough time promoting holistic health of his crops (although I

admit that if we were growing enough to sell, chances are we'd lower

our standards too). For someone just starting out, they could do

worse than to begin with a relatively mainstream book like this and

then slowly branch out into more permaculture techniques once they've

gotten their feet wet. Plus, Markham's cost-benefit analysis may

tempt some folks who otherwise wouldn't even consider gardening to try

their hand, so this might be the book to give to your in-laws if they

think your homesteading bug is crazy.

Some friends who were hiking

the Appalachian Trail dropped by today for a visit and a tour of the

garden.

Shannon and Dawn are the

folks who have been sharing their meat

rabbit adventures in the form of Tuesday guest posts.

Yes...horse manure with worms

really makes Anna that happy.

This past weekend was a time

of endings and beginnings. A heavy frost (nearly a killing

freeze) marked the last of the summer produce Saturday morning, and I

chopped up some of our final homegrown onions to enjoy in a chicken

soup with friends.

This past weekend was a time

of endings and beginnings. A heavy frost (nearly a killing

freeze) marked the last of the summer produce Saturday morning, and I

chopped up some of our final homegrown onions to enjoy in a chicken

soup with friends.

It was great to welcome Shannon back to the farm, and to

meet Dawn (and their well-travelled dog Downey). We sent them on

their way with oilseed radish seeds to try in their clay soil, and they

left us some Malabar spinach seeds, since the plant has thrived in

their Louisiana heat.

Now that they're safely

home with their rabbits, we can expect to hear more

from our southern correspondents soon. (Yes, Shannon, that was a

hint.)

Last year, I

summed up all of the chicken experiments I'd been posting about

throughout the year on our Avian Aqua Miser site, and I thought you might

enjoy seeing the highlights again this year.

One of the most timely

experiments I wanted to mention involved letting

our chickens free range in the woods over the winter. I was fascinated to

see that the flock concentrated most of their attention around the

bases of big trees, where they scratched through the mulch in search of

invertebrates. They only foraged over about three quarters of an

acre, probably because the flock had to stay close enough to the hen

house so that ladies could drop by at intervals to lay their eggs.

One of the most timely

experiments I wanted to mention involved letting

our chickens free range in the woods over the winter. I was fascinated to

see that the flock concentrated most of their attention around the

bases of big trees, where they scratched through the mulch in search of

invertebrates. They only foraged over about three quarters of an

acre, probably because the flock had to stay close enough to the hen

house so that ladies could drop by at intervals to lay their eggs.

The

forest worked as a good escape valve in the summer too, when the grasses stopped

growing and the ground began to look bare in their rotational

pastures. I think this system really depends on a quality

rooster, though, since when I tried the same trick with some  half-grown broilers, they

just sat on the other side of the pasture fence and begged to be let back

into their home turf.

half-grown broilers, they

just sat on the other side of the pasture fence and begged to be let back

into their home turf.

If you start

young chicks free ranging from week one and keep them close to the

house, they're the very best chickens to let run semi-wild. Having

trees or bushes available to hide in makes chicks (and

adult hens, for that matter) feel safer, so they spend more time

hunting wild food.

There

are reasons we don't let our main flock free range all the time, though. The book Free-Range

Chicken Gardens

gives some tips for helping chickens coexist with a garden during the

growing season, but we like to keep the garden extremely productive, so

the chickens get relegated to pastures after they reach two months

old. We were forced to clip

a couple of chickens' wings (and then eat one of them)

when they didn't toe the line and thought the garden was still fair

game during the summer months.

There

are reasons we don't let our main flock free range all the time, though. The book Free-Range

Chicken Gardens

gives some tips for helping chickens coexist with a garden during the

growing season, but we like to keep the garden extremely productive, so

the chickens get relegated to pastures after they reach two months

old. We were forced to clip

a couple of chickens' wings (and then eat one of them)

when they didn't toe the line and thought the garden was still fair

game during the summer months.

I don't feel like we

have much more experimenting to do with free range chickens. Our

system just works!

| This post is part of our 2012 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Day 1 of the new Skil 15 amp

circular saw started today.

Cutting logs of purchased

firewood in half will be the main application.

It cuts like a hot knife

through butter and highlights the cutting area with a laser.

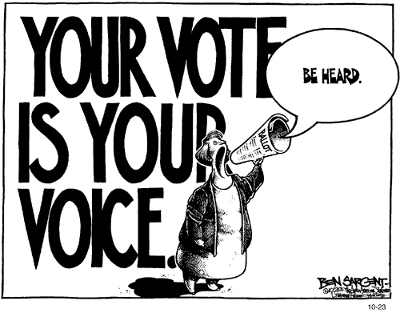

I promised myself that I

wasn't going to start a political debate about the election, but I did

want to remind our readers to do their civic duty and go vote.

And in the process I realized I had a lot of nonpartisan (but still

very controversial) voting advice I wanted to share.

I promised myself that I

wasn't going to start a political debate about the election, but I did

want to remind our readers to do their civic duty and go vote.

And in the process I realized I had a lot of nonpartisan (but still

very controversial) voting advice I wanted to share.

Vote. Yes, even if you're

disappointed in all the candidates, it is worth going out and

voting. Do your research first, though, so you'll know who

all the little guys are because...

Your

vote makes more of an impact locally. Even though it seems

like who wins the presidency is the most important aspect of today,

your state and local elections will actually have more of an influence

on your day-to-day life. Plus, your vote has more likelihood of

swaying the results of elections closer to home (and the issues are

easier to understand fully too). (Speaking of which, I am going to plug one candidate

--- if you live in Virginia's ninth congressional district like we do, I

have been on Anthony Flaccovento's farm and can personally vouch for

his farming techniques, along with his stances on other key

issues. Vote for Anthony!)

Don't

choose your political leaders based on charisma. This is my pet peeve,

so I'll try to be brief. U.S. elections have turned into a cult

of personality, which is why the only candidates who get elected

anymore are those with deep pockets who can make themselves look like

movie stars and turn their families into storybook characters.

Unfortunately, to get that much capital, nearly all of them have to

toady up to the big industry lobbyists, so none of them are ever going

to vote in such a way as to help the little guy. If you don't

approve of the cult of personality, make it a habit not to look at

photos or videos of your candidate or to listen to them speak --- you

may think this won't sway you, but it will. Figure out which

issues are important to you, then look up your candidates' voting

history (many websites provide this information on various issues) or

do some other primary research to figure out who is going to represent

the values you espouse, then vote accordingly.

Don't

vote selfishly.

There are so many people (and plants and salamanders) who have no say

in the election but whose lives will change drastically based on the

outcome, so I try to vote for what will make these disenfranchised

populations happier and healthier. Your personal bottom line

should not be the deciding factor in who you vote for.

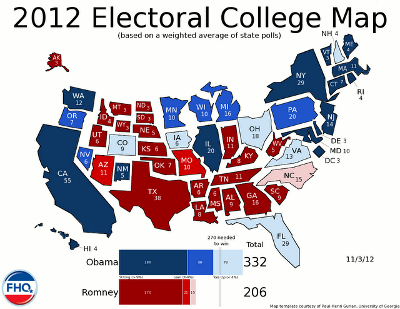

Before voting for a third

party candidate for president, please understand

the electoral college system. I hear so many people

saying they're going to vote for a third party candidate for president,

and it always makes me sad. Yes, I think anyone who runs for

president with the full support of the Democrat or Republican party is

crooked (see point number three), but you're literally throwing away

your vote if you select anyone else. A candidate has to receive

the majority of the popular votes in a state to get a single electoral

college vote, so unless you think 50% of the people in your state are

going to select the same third party candidate, your vote is

worthless. If you care about this issue, there are many people

working to reform our system --- for example www.nationalpopularvote.com --- but simply voting for a

third party candidate is putting the cart before the horse. Your

vote for a third party candidate makes a lot more sense at the local

level, though, especially if you talk your neighbors into doing the

same.

Before voting for a third

party candidate for president, please understand

the electoral college system. I hear so many people

saying they're going to vote for a third party candidate for president,

and it always makes me sad. Yes, I think anyone who runs for

president with the full support of the Democrat or Republican party is

crooked (see point number three), but you're literally throwing away

your vote if you select anyone else. A candidate has to receive

the majority of the popular votes in a state to get a single electoral

college vote, so unless you think 50% of the people in your state are

going to select the same third party candidate, your vote is

worthless. If you care about this issue, there are many people

working to reform our system --- for example www.nationalpopularvote.com --- but simply voting for a

third party candidate is putting the cart before the horse. Your

vote for a third party candidate makes a lot more sense at the local

level, though, especially if you talk your neighbors into doing the

same.

So how's that for a

political rant that 99% of our readers are bound to disagree with at

least partially? (And I didn't even have room to complain about all these glossy fliers showing up in my mailbox that aren't appropriate for kill mulches, worm bins, or even the wood stove!)

This year's experiments with

chicken pastures were mostly a streamlining of the process that we

started to hammer into shape in 2011. In general, our trials this

year had to do with improving wild pastures vegetated with whatever

sprung up after we cut the plants too tall for chicken beaks.

This year's experiments with

chicken pastures were mostly a streamlining of the process that we

started to hammer into shape in 2011. In general, our trials this

year had to do with improving wild pastures vegetated with whatever

sprung up after we cut the plants too tall for chicken beaks.

I found that mowing

the pastures as high

as possible (which isn't very high with our mower) after the chickens

are rotated to the next pasture cuts back the weeds that the flock

ignored. That gives chicken-friendly plants more space to

grow. It seems to be necessary to come back through with clippers

once in the summer, too, to

hit weeds along the fenceline that outgrew the mower. I can tell that this

simple maintenance duo is going to have our sunnier pastures

grass-filled in just a couple of years.

The three pastures under

heavy tree canopies are going slower at the grassing up process, so I

decided to take the opportunity to improve what's currently pretty poor

soil. I planted

buckwheat in one this summer, then replaced it with oilseed

radishes this

fall. The cover crops aren't thriving in this shade, but they are

producing some biomass. Hopefully we'll find time to take the

problematic trees down this winter and start replacing them with more

chicken-friendly bushes that are spaced far enough apart that they let

the grasses grow.

The three pastures under

heavy tree canopies are going slower at the grassing up process, so I

decided to take the opportunity to improve what's currently pretty poor

soil. I planted

buckwheat in one this summer, then replaced it with oilseed

radishes this

fall. The cover crops aren't thriving in this shade, but they are

producing some biomass. Hopefully we'll find time to take the

problematic trees down this winter and start replacing them with more

chicken-friendly bushes that are spaced far enough apart that they let

the grasses grow.

Meanwhile, I tried to convert

two other relatively barren pastures (also in the shade) over to

pasture plants that chickens enjoy. The trouble is that I

planted cover crops along with the grasses and clovers as a nurse crop,

and the former outcompeted the latter. I

did get some perennials to come up in one spot, but it was impossible to

keep the chickens off the tender growth this summer, and I think I

wiped my hard-won grass and clover out. I'm hopeful that the bare

ground left behind by the oilseed radishes will give me a good spot to

try again, but I'll have to commit to keeping the flock completely out

of that pasture until 2014.

Meanwhile, I tried to convert

two other relatively barren pastures (also in the shade) over to

pasture plants that chickens enjoy. The trouble is that I

planted cover crops along with the grasses and clovers as a nurse crop,

and the former outcompeted the latter. I

did get some perennials to come up in one spot, but it was impossible to

keep the chickens off the tender growth this summer, and I think I

wiped my hard-won grass and clover out. I'm hopeful that the bare

ground left behind by the oilseed radishes will give me a good spot to

try again, but I'll have to commit to keeping the flock completely out

of that pasture until 2014.

The one thing we did

right was to (mostly) prevent

overgrazing of the pastures this year. It really

helped to figure out temporary

fencing (and the free

range escape hatches

I posted about yesterday) so that we weren't forced to keep chickens on

over-used ground simply because we had nowhere else to put them.

As usual, I also spent a

lot of time peering at our poultry to see what they were actually

eating on pasture. I learned that (despite what the books say) winter

cover crops of oats and field peas  were ignored by our picky

flock, as were sweet

potatoes I tried to feed them whole and raw. On the other hand, winter

rye and mustards were pecked right up.

were ignored by our picky

flock, as were sweet

potatoes I tried to feed them whole and raw. On the other hand, winter

rye and mustards were pecked right up.

In a surprise

about-face, our chicks this year enjoyed both comfrey and oilseed

radishes (both of

which were on the no-good list for previous flocks). Cicadas and jewelweed

seeds were other new

hits.

I've got plenty of

experimentation ahead for improving our pastures, and an ebook in the

works to help others follow our lead without muddling through all of

our mistakes. Stay tuned to our chicken blog for a blow-by-blow, or wait

until next year's sum-up over here for more details.

| This post is part of our 2012 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We trimmed it back to 3 feet and tied the branches together.

I'm already looking forward to the 2013 fig harvest.

As Mark

mentioned last night,

our larger fig was ready to be swaddled just like his

younger sister.

The idea is that figs aren't really winter hardy here in zone 6, but

with some careful variety

selection and a

little love, you can

see get lots of fruits without babying a house plant.

I'd

read that Chicago Hardy figs do best if cut back drastically to three

main trunks each winter, but when I pulled out the clippers, I suddenly

couldn't decide if that meant three main trunks with all of their side

branches or just three sticks coming out of the ground. So I went

for a moderate approach where I removed any tiny branches and ones that

would be shaded, but left multiple branches on each trunk.

I'd

read that Chicago Hardy figs do best if cut back drastically to three

main trunks each winter, but when I pulled out the clippers, I suddenly

couldn't decide if that meant three main trunks with all of their side

branches or just three sticks coming out of the ground. So I went

for a moderate approach where I removed any tiny branches and ones that

would be shaded, but left multiple branches on each trunk.

Next, I cut the tree

down to about three feet high. Some people keep their figs tall

and wrap the whole thing up, but it was awfully nice having fruits I

could pick without a ladder, and I can protect what's left better if I

shorten this year's growth. By carefully bending and then tying

the branches together, they formed a compact bundle, giving me plenty

of room to stuff leaves around them within an enclosure I made out of

lightweight fence posts and trellis material.

I topped it all off with a

cheap tarp that came on our roofing

tin. I felt

like last year's

frost protection

lost some efficiency when rain pounded down the insulating leaves and

exposed the tips of the fig branches. Hopefully this year's tarp

will prevent moisture entering my fig enclosure from above.

I topped it all off with a

cheap tarp that came on our roofing

tin. I felt

like last year's

frost protection

lost some efficiency when rain pounded down the insulating leaves and

exposed the tips of the fig branches. Hopefully this year's tarp

will prevent moisture entering my fig enclosure from above.

I saved nearly all of

the small branches to try rooting next year, and three of them already

had little roots forming (since I cut those  branches

off below the mulch line). Usually you gather

scionwood in the late winter, but it was necessary to chop our fig

down before wrapping it, so now I'm stuck trying to decide how to store

these cuttings in a cool, damp, but not freezing spot all winter.

We're really going to have to try to excavate our fridge root cellar

soon....

branches

off below the mulch line). Usually you gather

scionwood in the late winter, but it was necessary to chop our fig

down before wrapping it, so now I'm stuck trying to decide how to store

these cuttings in a cool, damp, but not freezing spot all winter.

We're really going to have to try to excavate our fridge root cellar

soon....

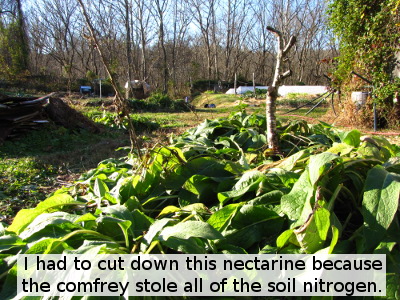

At least in our area, stone

fruits can be very problematic because they succumb to the fungal

disease brown rot.

In addition, many of them tend to lose flowers during frosts that come

behind spring thaws, so you may spend several years watching a

beautifully trained peach tree bloom without harvesting any

fruits. Assuming you don't have just the right microclimate to

keep them happy (early morning sun to dry the dew, low humidity in the

summer, and a full-sun site that's shaded during the winter),

you're once again stuck choosing varieties that will handle your

conditions without the necessity of chemical intervention.

At least in our area, stone

fruits can be very problematic because they succumb to the fungal

disease brown rot.

In addition, many of them tend to lose flowers during frosts that come

behind spring thaws, so you may spend several years watching a

beautifully trained peach tree bloom without harvesting any

fruits. Assuming you don't have just the right microclimate to

keep them happy (early morning sun to dry the dew, low humidity in the

summer, and a full-sun site that's shaded during the winter),

you're once again stuck choosing varieties that will handle your

conditions without the necessity of chemical intervention.

Sour cherries

are perhaps the most disease-resistant of the stone fruits, especially

if you select a variety like English Morello or Meteor. I've also

read about Mongolian-cross bush cherries (Valentine, Carmine Jewel,

Romeo, Juliette, Rose, and Crimson Passion), which are reputed to have

big fruits with lots of sugar, to be tolerant of clay soil, and to

fruit by the fifth year. Unfortunately, the sweet

cherries

I adore are very prone to getting frost-bitten, to

losing their fruits to brown rot, and to perishing in clay. (We

ripped out our dwarf sweet cherry after the Japanese beetles ate all

the leaves multiple years in a row and the few fruits rotted

away.) If you live in a damp climate like ours and have had good

luck with a sweet cherry, I'd love to hear about it.

Sour cherries

are perhaps the most disease-resistant of the stone fruits, especially

if you select a variety like English Morello or Meteor. I've also

read about Mongolian-cross bush cherries (Valentine, Carmine Jewel,

Romeo, Juliette, Rose, and Crimson Passion), which are reputed to have

big fruits with lots of sugar, to be tolerant of clay soil, and to

fruit by the fifth year. Unfortunately, the sweet

cherries

I adore are very prone to getting frost-bitten, to

losing their fruits to brown rot, and to perishing in clay. (We

ripped out our dwarf sweet cherry after the Japanese beetles ate all

the leaves multiple years in a row and the few fruits rotted

away.) If you live in a damp climate like ours and have had good

luck with a sweet cherry, I'd love to hear about it.

Peaches are more tolerant of

wet feet than cherries, but are very prone to lose fruit to bacterial

spot and brown rot. Disease-resistant varieties include:

- Early Redhaven

- Ernie's choice --- reputed to taste like a nectarine

- Garnet Beauty

- Harbrite

- Harcrest

- Harrow Beauty

- Harrow Diamond

- Glohaven

- Elberta

- Madison

- New Haven

- Raritan Rose

Nectarines

are simply a hairless peach, but most are especially prone to insect

and disease damage (as we found in our own garden). However

Hardired, Mericrest, Midglo, and RedGold have at least some disease

resistance.

Nectarines

are simply a hairless peach, but most are especially prone to insect

and disease damage (as we found in our own garden). However

Hardired, Mericrest, Midglo, and RedGold have at least some disease

resistance.

Although the beautiful

golden fruits of apricots

always tempt me in nursery catalogs, it sounds like I'd be better off

keeping my distance if I don't want to baby trees with little

reward. Of all the stone fruits, apricots are most likely to lose

their ultra-early flowers to frosts, they have no tolerance for wet

feet, and they get all the usual stone fruit diseases. Selecting

late bloomers like Alfred, Goldcot, Harcot, Harglow, Hargrand,

Harlayne, Harogen, Jerseycot, Precious, and Sugar Pearls will at least

weigh the odds in your favor.

(By the way, in case

you're wondering why so many frost- and

disease-resistant stone fruits have names starting with "Har", these

were developed at the Harrow Research Station in Ontario.)

Finally, we come to the plums, which are really two

species --- European plums (Prunus

domestica) and

Asian plums (Prunus

salicina).

The latter are less hardy, with zone 6 being their most northern

limit, require light soil, and need warm, dry summers. European

plums are better for most low-key gardeners since they can handle clay

and bloom later, so they skip some spring frosts, but they're less

likely to be disease resistant (with Seneca and Imperial Epineuse being

the only resistant varieties I saw listed). Disease-resistant

Asian plums include:

Finally, we come to the plums, which are really two

species --- European plums (Prunus

domestica) and

Asian plums (Prunus

salicina).

The latter are less hardy, with zone 6 being their most northern

limit, require light soil, and need warm, dry summers. European

plums are better for most low-key gardeners since they can handle clay

and bloom later, so they skip some spring frosts, but they're less

likely to be disease resistant (with Seneca and Imperial Epineuse being

the only resistant varieties I saw listed). Disease-resistant

Asian plums include:

- AU Roadside

- AU Rosa

- Methley (which is what we have, but it's not thriving in our clay)

- Satsuma

You can also check out

the more cold hardy Asian-American crosses, as

long as you're willing to work harder to get them pollinated.

Disease-resistant and hardy varieties include Alderman and Superior.

As usual, I'd love to

hear about the stone fruits you've grown without

chemical intervention. Be sure to mention your growing zone and

general region since many varieties do much better in certain areas

than others. I have a couple of spots that I might be able to

cram another tree into, and your tips will help me decide who makes the

cut.

Next week, we'll finish

up The

Holistic Orchard

by talking about

berries, but in the meantime you might enjoy previous posts about beginning

a holistic orchard, techniques

for designing a holistic orchard, orchard

soil health, managing

fungi in the orchard, and disease-resistant

pears. After that, we'll take a week off, then will start

reading Joel Salatin's Folks

This Ain't Normal,

which won the vote by a landslide!

An upcoming carrot harvest

pushed us into fixing the refrigerator

root cellar today.

It took some digging and

prying, but it's now sitting up straight.

Next we need to figure out a

way to anchor it in place and then build a roof that will divert the

water. The parsnips from 2009 were nowhere to be found.

Long-time readers will be

aware that I'm always trying to sneak new livestock onto the farm and

Mark's always reining me in. "Whoa, there!" he says. "Are

you ready for such a big commitment? Remember how much time the

garden and fruit trees and berry bushes and laying flock and broilers

take up, not to mention all this writing you're always poking away

at. Do you really think we have time to milk

a goat or fence

in an acre for sheep?"

Long-time readers will be

aware that I'm always trying to sneak new livestock onto the farm and

Mark's always reining me in. "Whoa, there!" he says. "Are

you ready for such a big commitment? Remember how much time the

garden and fruit trees and berry bushes and laying flock and broilers

take up, not to mention all this writing you're always poking away

at. Do you really think we have time to milk

a goat or fence

in an acre for sheep?"

I think I may have found

the perfect middle ground, though --- fattening a pair of hogs. This

fascinating page

suggests that you can raise a pair of pigs from 40 pounds (when they're

weaned) to 200 pounds for $500 ($1.39 per pound) if you do the

butchering yourself. The great part is that the whole process

only takes four months, so if we decide we hate swine, we only have to

live with them for 120 days.

(Even if we weren't pinching

pennies, we'd have to do the butchering on-farm. The idea of

walking a pig half a mile down our floodplain to the parking area and

then loading it up in our car to get to the slaughter-house sounds

tougher than skinning, gutting, and cleaning the hogs ourselves.

Bradley remembers killing hogs with his family as a kid, so I'll bet we

could get him to help us, and how much harder could it be than a deer?)

(Even if we weren't pinching

pennies, we'd have to do the butchering on-farm. The idea of

walking a pig half a mile down our floodplain to the parking area and

then loading it up in our car to get to the slaughter-house sounds

tougher than skinning, gutting, and cleaning the hogs ourselves.

Bradley remembers killing hogs with his family as a kid, so I'll bet we

could get him to help us, and how much harder could it be than a deer?)

In addition to providing

top-notch meat for $1.39 per pound, spending the summer with a pair of

pigs could be the first step toward reclaiming more quality pasture for

chickens (or other animals). As colonizing

livestock, pigs can

be living bush hogs if you leave the rings out of their noses, and all

of the areas we've considered expanding into would need a year or two

of this work before anything else could happen there.

As an added bonus,

there's always the

manure to

consider. Plus, increased diversity on a homestead usually seems

to lead to increased efficiency, in this case resulting from the pigs

eating some garden waste the chickens aren't interested in. And I

just love experimenting with new things.

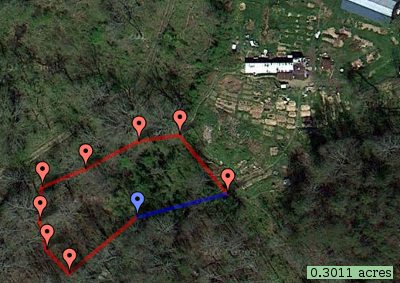

My

reading suggests that a third of an acre divided into four paddocks

would be sufficient pasture for a pair of growing swine. I've got

the perfect spot in mind too --- a little plateau just southwest of our

core homestead with lots of scrubby growth that can come out and two

big oak trees that would stay put and drop mast (acorns) into the

pasture. The question is, how crazy am I to want to spend $1,550

on a livestock panel fence that will last the rest of our lives and

allow us to graze anything we want in there forever, versus a small

fraction of that sum on electric fencing?

My

reading suggests that a third of an acre divided into four paddocks

would be sufficient pasture for a pair of growing swine. I've got

the perfect spot in mind too --- a little plateau just southwest of our

core homestead with lots of scrubby growth that can come out and two

big oak trees that would stay put and drop mast (acorns) into the

pasture. The question is, how crazy am I to want to spend $1,550

on a livestock panel fence that will last the rest of our lives and

allow us to graze anything we want in there forever, versus a small

fraction of that sum on electric fencing?

And, of course, is

raising a pair of weanling pigs much more work than I imagine?

I'd be curious to hear from others who have tried a similar small-scale

operation. If we figured out the fencing and housing over the

winter, would day-to-day pig care drive me nuts during the busy garden

season?

(What do you think,

Mark? Are you sold?)

When we moved our chickens

from tractors to a coop and rotational pasture system, we had to deal

with manure for the first time. Deep

bedding was the

perfect solution, but we did run into a few minor problems this year.

When we moved our chickens

from tractors to a coop and rotational pasture system, we had to deal

with manure for the first time. Deep

bedding was the

perfect solution, but we did run into a few minor problems this year.

The real cause of the

trouble is that it's tough to find enough high carbon biomass to fill

the coops (and to keep filling them as manure builds up). Autumn

leaves are may favorite, and I've tried a bit of the sawdust we

bought for the composting toilet, with good results.

But when I ran low on optimal bedding, I decided to try treating

the coop floor as a compost pile.

The positive side is

that I was no longer creating bare patches in the pastures where I

threw our food scraps. Unfortunately, the scent of sweet corn

cobs was irresistable to the neighborhood raccoon, who came for the scraps and

stayed for a chicken

dinner. The hen he was hunting got away, but it took us weeks of

effort to make our flock feel comfortable in the coop again. Now

corn cobs go in the worm bin, and the raccoon seems willing to stay in

the woods.

stayed for a chicken

dinner. The hen he was hunting got away, but it took us weeks of

effort to make our flock feel comfortable in the coop again. Now

corn cobs go in the worm bin, and the raccoon seems willing to stay in

the woods.

The issue of never

having enough high carbon materials is one we run into in the garden as

well, and I've got all kinds of ideas for solving the conundrum.

Maybe we'll commit some open areas along the sides of our homestead to

growing rye for straw, or we'll plant a high quality leaf tree (sugar

maple is my favorite) in a pasture that stays mowed so raking leaves

will be easy. We're also pondering chop 'n

drop plants,

although that will probably be less helpful for the chicken coop than

for the garden.

But these issues aside,

deep bedding has been a boon to our farm. Having that high

quality mulch/compost to topdress the berries with this spring was

worth every minute of coop maintenance!

| This post is part of our 2012 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

29 bales delivered and stacked for 145 dollars.

It might be enough to get us through the Autumn mulching frenzy.

One

of the most exciting things for me about having a book in print is the

idea of my loyal blog readers stumbling across it in their library,

bookstore, or Tractor Supply. The

Weekend Homesteader is already available in some bricks and mortar

sales locations and should be hitting most of them this coming week, so it's

time for a scavenger hunt!

One

of the most exciting things for me about having a book in print is the

idea of my loyal blog readers stumbling across it in their library,

bookstore, or Tractor Supply. The

Weekend Homesteader is already available in some bricks and mortar

sales locations and should be hitting most of them this coming week, so it's

time for a scavenger hunt!

It's easy to play (and

you may even win a prize). Just snap a photo of yourself with my

book, whether in your bedroom or out in the world, and email

it to anna@kitenet.net,

post it somewhere else and link to it in a comment below, or put it on our

facebook page by

Sunday (November 18) at midnight. I'll pick one photographer at

random and mail you a signed copy --- there aren't many of these

floating around because I'm not selling them, only giving them to my

favorite people.

Meanwhile, if you'd like

a bit more substance, check out my

Destiny Survival Radio Interview. (I'm actually afraid

to listen to it since I'm not a very good public speaker, but at least

you'll hear my Appalachian accent before I get confused halfway through

the phrase "your eyes are bigger than your stomach.") Readers

might instead like this guest post about when

emergencies are a fact of life better. Or check out two of my favorite book reviews so far, one by my sister, and one on About.com.

Thanks for reading (and

scavenging!)

Last year, I faced a lot

of growing pains when it came to hatching our own chicks and keeping

them alive, but now I feel like an expert. Hatch rates this year

ranged from 80% to  95%, and survival rates (how

many chicks lasted through their first month of life) were always right

at 95%.

95%, and survival rates (how

many chicks lasted through their first month of life) were always right

at 95%.

To get there, I perfected my choice

of eggs to go in the incubator, tweaked my dry

incubation

technique, and learned

how to leverage my specific incubator. I also prevented a

lot of second-guessing by figuring out how

to tell if eggs left in the incubator on day 22 were late-hatchers or

duds. More

basically, I started taping

my incubator and turner plugs to the wall socket to prevent accidental

unplugging.

Once the chicks made it

out of the egg, we continued to have good results with an Ecoglow

Brooder instead of a

heat lamp. Mark built me an outdoor

brooder that did a

great job to keep

the chickens happy outside as early as week 1, which saved my sanity and

also let them enjoy

free ranging much

earlier in life. Turning the plexiglass toward the sun helped

heat up the brooder in the early spring, then flipping the window side

to face north (and  putting the brooder in the

shade) prevented overheating for our summer flocks.

putting the brooder in the

shade) prevented overheating for our summer flocks.

I feel like I've finally

got chick care figured out, which is why I wrote Permaculture

Chicken: Incubation Handbook to jumpstart others'

journeys. If you want to see more cute chick photos without

spending 99 cents, you might also want to check out this

post.

| This post is part of our 2012 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I bought the small stainless

steel anchor at Walmart in the RV section.

When we got it home it

started to look too weak for the refrigerator

root cellar.

The bigger black anchor is

what people use to secure a mobile home to the ground. I found ours

today at a mobile home supply store in Coeburn for 8 dollars a piece.

It was a struggle to sink it all the way in to our clay ground, which

is a good sign that it's stuck in place and won't budge.

The real reason I moved

our refrigerator

root cellar resurrection to the top of the list is

that lows have hit 22 and there's no more room in our real fridge for

the rest of the cabbages and carrots. If I didn't want them to

freeze and ruin in the garden, these crops needed to find some cool,

damp storage immediately.

It's a bit risky to fill

the refrigerator root cellar up with valuable crops when we don't know

for sure if it'll hold

above-freezing temperatures (and refrain from falling

over again).

On the other hand, you can look at this a bit like putting tomato

plants in the forest garden --- a wheelbarrow load of

carrots is going to ensure I pay attention to our new experiment.

If there's a problem, we won't be waiting three years to fix it this

time.

Usually, I sort my

carrots, putting the few that are broken, nibbled, starting to rot, or

excessively small on top for immediate consumption. But I don't

really know the intricacies of our fridge root cellar yet, so I opted

to leave the carrots all mixed together. That way I'm hedging my

bets --- if one area doesn't work right, all of my best carrots won't

happen to be there.

I packed some of the

carrots in sawdust and left some plain as an extra experiment.

While the keeping quality of the crops will be the real indicator of

root cellar function, Mark also tossed in a max./min.

thermometer. I'm ordering another analog

version since I have

a feeling the digital one won't last long in the damp conditions.

If the fridge works as

planned, I can see another one in our future. An afternoon's work

filled our current unit halfway up, and I haven't even moved our white

potatoes and fig scionwood out there yet. And once we start

having apples, we'll want to keep them in their own unit so the

ethylene given off by the fruits doesn't spoil the vegetables. So

many exciting experiments ahead!

The refrigerator

root cellar has 2 anchor

points. One on the right side and the other in the back.

I chose to use a medium sized

U-bolt, but it's possible two holes big enough to loop some 12 gauge

wire through might be enough.

Each point in the ground is

lower than the refrigerator anchor, giving it a downward tug along with

the side ways tension.

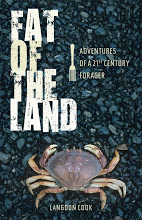

Fat

of the Land was a

fun read, but I'm afraid it only provided one tidbit of wildcrafting

information I might use (baking with dandelion petals). Instead,

the series of essays follows the hunt for one wild delicacy after

another, most of which are seafood and require extreme feats to

harvest. (Those of you who live closer to the shore are more

likely to get useful factual information from the book.)

Fat

of the Land was a

fun read, but I'm afraid it only provided one tidbit of wildcrafting

information I might use (baking with dandelion petals). Instead,

the series of essays follows the hunt for one wild delicacy after

another, most of which are seafood and require extreme feats to

harvest. (Those of you who live closer to the shore are more

likely to get useful factual information from the book.)

Even though it's only

moderately educational, the book is beautifully written and

inspirational. I found it fascinating to follow the culinary

journey of a mainstream American who admits that his cooking prowess

mostly consisted of opening cans before he started hunting down wild

food. I'd definitely add Fat

of the Land to

the homesteading-beach-read genre.

I'm not sure how many

Brussels sprouts we'll get before extreme cold wipes the plants out,

but our first harvest netted rave reviews from Mark. I tossed

them with olive oil, salt, and pepper and roasted them in the oven

until they turned bright green. "These are even better than roast figs!" proclaimed my kind husband.

I'm not sure how many

Brussels sprouts we'll get before extreme cold wipes the plants out,

but our first harvest netted rave reviews from Mark. I tossed

them with olive oil, salt, and pepper and roasted them in the oven

until they turned bright green. "These are even better than roast figs!" proclaimed my kind husband.

Of the bulkier crucifers

(exempting the leafy greens), broccoli is the most frost tender.

Even though ours are still churning

out side shoots,

these are less crisp and I can tell the harvest is coming to an

end. Our cabbages survived hard freezes in the garden, but I

opted to move

them to the root cellar to ensure they don't die

before winter feasts use them up. Meanwhile, the Brussels sprouts

seem largely unaffected by lows that have nearly hit 20.

The extra cold hardiness is a

boon because Brussels sprouts take forever to ripen up. We

planted ours at the same time as the cabbage and broccoli, and have

only had a small handful to eat. I'm hopeful that we'll get more

sprouts all the way through to December, and if not, I'll just plant

earlier next year --- I'm starting to get the impression Mark could eat

Brussels sprouts every day in November just like we enjoyed broccoli in

October.

The extra cold hardiness is a

boon because Brussels sprouts take forever to ripen up. We

planted ours at the same time as the cabbage and broccoli, and have

only had a small handful to eat. I'm hopeful that we'll get more

sprouts all the way through to December, and if not, I'll just plant

earlier next year --- I'm starting to get the impression Mark could eat

Brussels sprouts every day in November just like we enjoyed broccoli in

October.

Our customers have turned DIY kits into an astonishing number

of efficient and beautiful waterers over the last year. Some of

them won prizes for their efforts (and if you're a chicken keeper, you

should be aware that our automatic

chicken feeder contest

is still in effect until November 16). Others simply shared their

designs for the joy of it.

Our customers have turned DIY kits into an astonishing number

of efficient and beautiful waterers over the last year. Some of

them won prizes for their efforts (and if you're a chicken keeper, you

should be aware that our automatic

chicken feeder contest

is still in effect until November 16). Others simply shared their

designs for the joy of it.

The photo to the right

shows Robert's

no-perch chicken waterer and the image at the top of

the page is a chicken

waterer that fills automatically from rainfall on the coop roof. (The inventor of the

latter tweaked

his design to work in tractors too.) Meanwhile, Michael

performed an awesome experiment to determine the exact angle at which

our nipples begin to leak.

Other favorite customer

experiments include a

waterer made out

of a five gallon bottle, a funnel

and hose technique

to make our premade

waterers easy to fill from outside the

coop, and a drip

tray so the coop

floor always stays dry even if you  have

a messy drinker.

have

a messy drinker.

Closer to home, Shannon

tentatively determined that our waterers might work for rabbits too, and Mark streamlined our heat

tape bucket waterer to stay thawed down into the teens.

We're looking forward to

seeing more beautiful designs (and chickens) over the next year.

Be sure to stay tuned to our chicken blog or facebook

page if you want to

know about upcoming contests in a timely manner.

| This post is part of our 2012 Chicken Experiments lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I discovered today that the

golf cart can haul 10 bales of straw.

While going up the ford I

noticed the LED indicator dimmed and the motor felt like it was

struggling.

Maybe it could've handled

another load with 10 if it had a full charge, but I decided to play it

safe and reduce the amount of bales to 7 per trip.

We barely got them all in the

barn before a storm started pouring down on us. My guess is this is the

start of our winter raining season which might last till early summer.

The last weed and mulch

episode in the garden is never at the top of my priority list, but I

know from experience that every hour's work now saves two hours during

the next growing season. So we took advantage of a handy visitor and some barefoot weather to

finish slipping straw around the greens in the mule garden.

All that's left to mulch

is about half the perennials, then we'll be going into winter more

ship-shape than ever before. I generally run out of warm weather

before I run out of weeds, but not this year!

We started with our first

rabbit, a New

Zealand White, sometime during the late spring. (He's the one

in the picture to the right relaxing on a bottle of ice water during

our summer heat.) He was a young male that was purchased from a

local feed store and was the only meat rabbit they had left.

We started with our first

rabbit, a New

Zealand White, sometime during the late spring. (He's the one

in the picture to the right relaxing on a bottle of ice water during

our summer heat.) He was a young male that was purchased from a

local feed store and was the only meat rabbit they had left.

While we were searching out other available rabbits in the local area,

our new neighbors who had just moved in offered us a pair of New

Zealand Whites. The rabbits were apparently a gift for their son

but they weren't too keen on keeping them around. The rabbits

were both a bit older than our first rabbit, and I'd estimate they had

a full 6-8 weeks in age on our young buck. This turn of events is

how we ended up with two males and one female. Obviously not the

ideal mix of male-to-female ratio, but hey... two of them were

free.

When we discussed breeding,

we considered the possibility that the free pair from our neighbors

were likely closely related and possibly siblings. Some

literature Dawn read from the library actually encourages inbreeding of

rabbits, but that seems so counter to everything we have learned in the

past that we will likely shy away from that. So, we decided we'd

breed the storebought male with the donated female. Later we'll

find another female (possibly a Californian) to breed with our other

male. That will give us a 50/50 mix and two breeding pairs.

Sometime in the last month or two our

purchased male finally reached maturity, so the question became when

did we want to breed them and have our first litter arrive?

Ideally, we'd have the arrival timed when we are both around. I

travel a bit for work, and we didn't want to time it for when I'd be

gone. Also, we wouldn't want to time it during potential holidays

or vacation time (like our recent NC & VA trip when we visited

Anna & Mark). So, this past weekend ended up

being the "big date" for our rabbit pair, constrained by our schedules.

Sometime in the last month or two our

purchased male finally reached maturity, so the question became when

did we want to breed them and have our first litter arrive?

Ideally, we'd have the arrival timed when we are both around. I

travel a bit for work, and we didn't want to time it for when I'd be

gone. Also, we wouldn't want to time it during potential holidays

or vacation time (like our recent NC & VA trip when we visited

Anna & Mark). So, this past weekend ended up

being the "big date" for our rabbit pair, constrained by our schedules.

If all goes well, our doe will have a litter sometime around December

10th. I'm hoping that the entire process will be uneventful and

require little from us other than providing some bedding and cleaning

of the hutch. Cold weather might be a concern, but we'll see how

it goes. Winters are typically pretty mild around here and if we

have to we can insulate or heat the hutch. If we're lucky, the

weather will be fine and temperature will not be a concern.

The process of breeding was

fairly uneventful. We rounded up the female, removed the box from

the male's hutch so that there'd be more room, and then placed the

female on his side. Generally, the female should always be

brought to the male. The other way around apparently can turn

violent as the female will often defend her turf.

The process of breeding was

fairly uneventful. We rounded up the female, removed the box from

the male's hutch so that there'd be more room, and then placed the

female on his side. Generally, the female should always be

brought to the male. The other way around apparently can turn

violent as the female will often defend her turf.

Female rabbits are reflexive ovulators and some of the reading that

Dawn has done suggests that they should be bred multiple times in the

course of a day or two. We tried this, but "date #2" didn't go as

well as the first time around. She wasn't having any of it the

second day, so we will see if this was a successful pairing or

not. When we first placed the female in the male's hutch, there

was a bit of chasing, but there was no fighting. We were a bit

concerned about whether or not there would be a battle but they seemed

to be pretty well behaved as they did what comes naturally.

One thing we will have to do

to prepare over the next couple of weeks is to modify the nesting box

so that it has a hinged top allowing access to the litter. Dawn

is the expert here as she's done all the reading on the topic.

She's also the one who built the boxes for our rabbits and probably

will be the one to modify the female's nesting box.

We'll need to decide quickly what

kind of nesting material we will place in the hutch. There are

several options; some are readily available materials (hay, grass,

leaves), while others are available commercially (bagged cellulose,

etc.) The literature claims that when she is preparing to have a

litter, the doe will use available nesting material and combine that

with fur which she pulls out of her coat. When cleaning the

netsting box they say to change the hay (or other material) and put the

fur back with new nesting material.

We'll need to decide quickly what

kind of nesting material we will place in the hutch. There are

several options; some are readily available materials (hay, grass,

leaves), while others are available commercially (bagged cellulose,

etc.) The literature claims that when she is preparing to have a

litter, the doe will use available nesting material and combine that

with fur which she pulls out of her coat. When cleaning the

netsting box they say to change the hay (or other material) and put the

fur back with new nesting material.

I'm sure we'll make some

discoveries along the way and will learn in the process. With any

luck, we'll have some cute bunny pictures to share soon. We've

just got to stay unattached to the cute fuzzballs so that we cannot

feel bad when it comes time to put them in the oven!

I'm sure we'll make some

discoveries along the way and will learn in the process. With any

luck, we'll have some cute bunny pictures to share soon. We've

just got to stay unattached to the cute fuzzballs so that we cannot

feel bad when it comes time to put them in the oven!

Shannon and Dawn

will be sharing their experiences with raising meat rabbits on Tuesday

afternoons. They homestead on three acres in Louisiana when time

off from life and working as a sys admin permits.

I once tried to use a shop vac

hose to divert our sawdust into a 5 gallon bucket, but it only lasted a

week before it came loose.

What I should've done was to

order one of these collection bags that came with the new 15 amp

saw.

The price is 10 to 20 dollars

for the small, and it's much less painless than trying to re-invent the

wheel.

The first set of dwarf trees

for our high density apple planting has arrived! (We ordered from

two different nurseries, so a couple more trees are yet to come.)

After soaking the roots all morning, Everett and I put them in the

ground...and then I pored over websites to figure out how to prune and

train my new trees.

The first set of dwarf trees

for our high density apple planting has arrived! (We ordered from

two different nurseries, so a couple more trees are yet to come.)

After soaking the roots all morning, Everett and I put them in the

ground...and then I pored over websites to figure out how to prune and

train my new trees.

The North

Carolina Cooperative Extension Service warns:

In other words, this isn't a guess-and-try-again system. I need to have all my ducks in a row from the get-go if I want to eat homegrown apples in 2014.

Understanding the goal

Although this post is really

about how to prune and train high density apples for their first year

of life, it's always essential to understand the final form you're

looking for. If left to their own devices, dwarf apple trees can

grow 10 to 15 feet tall and 12 to 16 feet wide, spending lots of energy

on vegetative growth and not fruiting for several years. Our goal

is to create a tree that tops out at 8 to 10 feet tall, fruits the

second year after planting, and doesn't bother its neighbor three feet

down the row.

Although this post is really

about how to prune and train high density apples for their first year

of life, it's always essential to understand the final form you're

looking for. If left to their own devices, dwarf apple trees can

grow 10 to 15 feet tall and 12 to 16 feet wide, spending lots of energy

on vegetative growth and not fruiting for several years. Our goal

is to create a tree that tops out at 8 to 10 feet tall, fruits the

second year after planting, and doesn't bother its neighbor three feet

down the row.The perfect high density apple tree is a lot like a normal central leader tree, but more compact. Branches start 24 to 32 inches off the ground and continue to the top of the tree, spaced only about six inches apart and growing no more than four feet long. After three to five years, some of these branches may need to come out, but we're not worrying over that during year one.

In order to support the weight of apples (and to keep the tree upright on nonvigorous rootstock), a permanent stake or trellis must be attached every 15 to 24 inches along the entire trunk. We're still deciding what to use for our support, but the main choices among large-scale orchardists seem to include 10 foot lengths of one inch metal pipe (or a slightly larger treated wooden post) sunk two feet in the ground, or hefty trellises.

Pruning and training the new tree

Okay, now that the big

picture is firmly engrained in our minds, let's look at what we want to

do to our tree during its first year of life. I've written

previously about planning

out the orchard, so

let's assume your trees are in the ground, with the graft union three

to four inches above the soil surface, and staked in some way.

Okay, now that the big

picture is firmly engrained in our minds, let's look at what we want to

do to our tree during its first year of life. I've written

previously about planning

out the orchard, so

let's assume your trees are in the ground, with the graft union three

to four inches above the soil surface, and staked in some way.The North Carolina Extension Service has another relevant admonition for this early stage: "Research has shown that any pruning of young trees will reduce or delay fruit production early in the life of the orchard." In other words, even though our main goal is to keep these trees small, we don't want to cut away much (if any) wood --- instead, we're focusing on training to keep the tree in line. The only branches worth cutting are damaged, are located less than 18 inches above the ground, or are more than half the diameter of the main trunk. (If you didn't spring for a well-feathered tree and are instead starting with an unbranched whip, you'll have to do some cutting, but that's a topic beyond the scope of this post.)

While your pruning shears are verboten, you do need to commit to training the tree right away and then monthly throughout the summer. Using toothpicks, clothespins, and/or tie-down strings, you want to spread all side branches down close to horizontal right away, then continue to spread them (and any secondary branches) level throughout the year.

Different sources recommend

different final orientations, ranging from just above horizontal to a

bit below horizontal. Usually, more vigorous trees and those

planted closer together have their branches pulled lower, which serves

to "calm" the tree --- meaning that the leader grows tall, but the side

branches spread more slowly and focus on making flower buds instead of

vegetative growth. Regardless of which orientation you choose to

train to, you want to keep an eye on new twigs all through the summer

and pull them downward then they reach three to four inches long.

Different sources recommend

different final orientations, ranging from just above horizontal to a

bit below horizontal. Usually, more vigorous trees and those

planted closer together have their branches pulled lower, which serves

to "calm" the tree --- meaning that the leader grows tall, but the side

branches spread more slowly and focus on making flower buds instead of

vegetative growth. Regardless of which orientation you choose to

train to, you want to keep an eye on new twigs all through the summer

and pull them downward then they reach three to four inches long.Since flower buds on apples are formed in July, it's essential to give your trees lots of love right away if you want fruits their second year. That's why we're planting in fall and committing to water starting with the first spring dry spell, hoping for early fruits. If you don't live in a wet-winter area, you might want to water all winter long.

Maintenance training and pruning

For now, we'll have plenty on our plates keeping our new dwarf trees happy and in line, but we also need to look ahead to the future. By the end of their second year, the trees should be about eight feet tall, at which point we'll need to choose a method of slowing their upward yearnings without promoting vegetative growth. This website gives a great year-by-year tutorial on planting and maintaining high density apples, and I'll be referring back to it frequently in the years ahead.

Our chicken waterer is the low

maintenance solution to chicken-care, allowing you to spend time on

fiddly dwarf apples.

If the endless talk of pests

and disease in the rest of The

Holistic Orchard

didn't scare you away, you probably felt the same relief I did when you

hit the Berries chapter. Not only do many brambles and bush

fruits bear much sooner than trees, they also tend to be more resistant

to problems, allowing you to make selections based on taste and

regional location.

If the endless talk of pests

and disease in the rest of The

Holistic Orchard

didn't scare you away, you probably felt the same relief I did when you

hit the Berries chapter. Not only do many brambles and bush

fruits bear much sooner than trees, they also tend to be more resistant

to problems, allowing you to make selections based on taste and

regional location.

I've written extensively

about brambles in Weekend

Homesteader: February,

and Phillips agrees with me on most points. Blackberries and

raspberries are easy and delicious --- select among the many varieties

based first on your growing zone and you'll be golden.

Blueberries

are tougher for those of us without highly acidic soil, but Phillips

offers some fascinating holistic advice there. First, he reminds

us that the main issue with alkaline soil is that it makes iron less

available to the blueberry roots, which tend to hunt for minerals right

at the mulch/soil interface. So adding greensand (rich in iron),

acidifying sources of nitrogen (such as cottonseed meal), old nails, or

sulfur (for fast acidification, in

a pinch) right below the mulch is much more effective than struggling

to change the pH of the whole rooting zone. Lots of organic

matter is very helpful long term too. Another issue blueberries

have with high pH is excess calcium blocking their taste for magnesium,

which can be fixed by boosting levels of the latter. Finally, if

you don't live too far north, southern highbush blueberries or (even

better) rabbiteye

blueberries are less

sensitive to high pH.

Blueberries

are tougher for those of us without highly acidic soil, but Phillips

offers some fascinating holistic advice there. First, he reminds

us that the main issue with alkaline soil is that it makes iron less

available to the blueberry roots, which tend to hunt for minerals right

at the mulch/soil interface. So adding greensand (rich in iron),

acidifying sources of nitrogen (such as cottonseed meal), old nails, or

sulfur (for fast acidification, in

a pinch) right below the mulch is much more effective than struggling

to change the pH of the whole rooting zone. Lots of organic

matter is very helpful long term too. Another issue blueberries

have with high pH is excess calcium blocking their taste for magnesium,

which can be fixed by boosting levels of the latter. Finally, if

you don't live too far north, southern highbush blueberries or (even

better) rabbiteye

blueberries are less

sensitive to high pH.

Gooseberries

and currants don't

like high heat, but that same personality trait makes them some of the

few fruits that will produce in the shade. We chose gooseberries

in our garden since we like fresh fruits much more than preserves, but

jelly-eaters might prefer currants. Disease is more likely to be

a problem with these plants than with other small fruits, though, so

select carefully to ensure you get both resistance and flavor.

Gooseberries

and currants don't

like high heat, but that same personality trait makes them some of the

few fruits that will produce in the shade. We chose gooseberries

in our garden since we like fresh fruits much more than preserves, but

jelly-eaters might prefer currants. Disease is more likely to be

a problem with these plants than with other small fruits, though, so

select carefully to ensure you get both resistance and flavor.

Interestingly, Phillips

doesn't throw in many unusual fruits, but does devote a whole section

to elderberries. I think this choice is due to his wife's

profession (herbalism) and to elderberries' healing powers. In

our garden, wild elderberries come up everywhere, and I mostly root

them out, but I have let one shrub grow up beside our biggest

peach. The bush attracts lots of pollinating insects, but the

fruits didn't pass my raw taste test.

Meanwhile, I was sad to see

that Phillips skipped grapes --- they're not technically berries, but I

could have used some holistic advice about these fungus-prone

fruits. And I think strawberries merit a place even if they're

not woody plants --- they certainly bear like crazy with few issues.

Meanwhile, I was sad to see

that Phillips skipped grapes --- they're not technically berries, but I

could have used some holistic advice about these fungus-prone

fruits. And I think strawberries merit a place even if they're

not woody plants --- they certainly bear like crazy with few issues.

Which fruits did you

wish had made the cut? Do you find some of the small fruits

listed more or less hardy than Phillips suggested?

I appreciate you all

hanging in there through a mind-bending couple of months considering

fruit trees. Those of you who haven't been reading along might

want to check out older posts about beginning

a holistic orchard, techniques

for designing a holistic orchard, orchard

soil health, managing

fungi in the orchard, disease-resistant

pears, and no-spray

stone fruits.

Meanwhile, the consensus

is for Joel Salatin's Folks,

This Ain't Normal to

be our next book club read. We'll skip Thanksgiving week, then

dive right into chapters 1 through 3 on November 28. Salatin is

bound to provoke lots of opinions, whether you agree with him or not,

so be sure to find a copy so you can join in the discussion!

A good

pry bar threaded through

the top holes works good for driving in these mobile home dirt anchors

for the refrigerator

root cellar.

It took a good 10 minutes of

heavy turning to get it sunk in where I wanted it.

Makes me wonder if these

anchors would hold on tight enough to help winch a truck from being

stuck? I know...sounds like a terrible idea that could end in a

horrible mess if the truck pulled the anchor out and it catapulted

towards an innocent bystander.

I'm not sure we can

believe the report of 99% humidity in our refrigerator

root cellar, but the

temperatures recorded over the last week (high of 54 and low of 43) are

probably accurate. Since we've had outside temperatures between

20 and 70 during that time period, the low-cost root cellar seems to be

doing its job admirably!

We had a nice heavy

rain, too, which is at least a partial test for the tie

downs. In  retrospect, I think two other

design changes make it much less likely for our fridge to collapse again. First, we

slanted the fridge back into the hill for version 2.0, and (perhaps

more importantly) we left off the retaining

wall wings.

retrospect, I think two other

design changes make it much less likely for our fridge to collapse again. First, we

slanted the fridge back into the hill for version 2.0, and (perhaps

more importantly) we left off the retaining

wall wings.

I suspect the wings were

the real cause of the initial root cellar slump. All of the loose

dirt on either side of the fridge pushed against the retaining wall,