archives for 10/2012

Grow

Fruit Naturally

by Lee Reich is a good starter book for those interested in growing

organic fruit, and will definitely be a handy reference to keep on my

bookshelf for the next few years. It's actually quite similar to

the same author's The Pruning

Book, both in pros

and cons.

Grow

Fruit Naturally

by Lee Reich is a good starter book for those interested in growing

organic fruit, and will definitely be a handy reference to keep on my

bookshelf for the next few years. It's actually quite similar to

the same author's The Pruning

Book, both in pros

and cons.

On the positive side, Growing

Fruit Naturally

is linear and hits all of the salient points concisely. On the

negative side, despite the title, the book really covers only

mainstream organic methods, not the cutting edge permaculture

techniques of nurturing full-ecosystem health that you'll find in The

Holistic Orchard.

In the end, I recommend

the book for beginners, and for intermediate fruit-growers like myself

who still need a reminder every year before they prune their

grapes. On the other hand, if you've been orcharding for a

decade, you might want to give this book a pass.

Once

a week, all through September, I've dreamed about figs. Black

ones, brown ones, plump and enticing, and always just out of reach.

Once

a week, all through September, I've dreamed about figs. Black

ones, brown ones, plump and enticing, and always just out of reach.

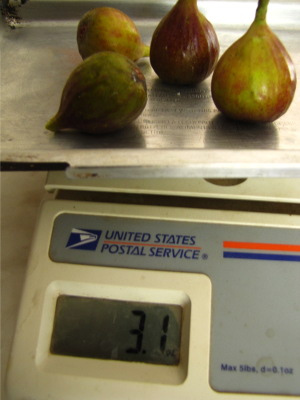

The source of my

obsession: our Chicago

Hardy fig has been

ripening up about a fig a day. I wait until we have three to

five, then cut them in half and roast them the easiest way possible ---

in the toaster oven under the highest heat until the juices puddle on

the tray and hit hard ball candy stage.

I've read that a mature

fig tree will bear thirty pounds of fruit per year, but I find that

hard to believe. At twenty figs to a pound, we'd have to multiply

our yields by 15 to become average. Even though older trees bear

more, here at the cold hardiness limit of the fig range, I can't expect

my tree to grow to true fig size.

While I yearn for figs

in my sleep, Mark gets practical. Having cleared the gully of

brambles this summer, he envisions that prime planting ground turning

into a fig paradise. One day, he brings Celeste home to begin Figlandia.

Meanwhile, I've started

a kill mulch at the shady end of the front garden to create a perennial

propagation bed. Brian has offered to trade scionwood with me, so

I'll be trying to root hardwood cuttings this winter and soon we'll be

trying some more varieties.

This post is your

warning --- you'll probably be hearing far more than you'd want about

figs for the next little while (especially this week at lunchtime). I can't help it. Figs

appear to be the fruits of my dreams.

| This post is part of our Fig lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It seems like our chicks get

more aggressive with their foraging right after it rains.

Maybe bugs are easier to find

or they feel extra hungry after waiting for the rain to stop. Either

way adds up to some quality entertainment on a rainy Monday.

A cold, rainy day

enticed me to break through one of my mental blocks and go visit with

our fans on facebook.

I'd been meaning to run

a no-holds-barred chicken photo contest, and this seemed like the way

to do it. A cool app makes it possible for anyone to

upload images and vote on the results --- you just have to become

a fan of Avian Aqua Miser first.

The photo deadline is

next Monday and voting ends a week from Friday. The winner gets a

free chicken waterer. (More details on the

contest page.)

Even if you don't have

chickens, you'll probably enjoy perusing the entries and voting on your

favorite. And if you need another rainy day activity, I've set Weekend

Homesteader: January (which includes an introduction to chickens,

along with bread baking, soil testing, and emergency lighting) free on

Amazon today. Happy October!

There seem to be a couple of

different lines of thought on how to best feed pets and

livestock. For many years I have not followed what seems to

be the popular wisdom and have had good results as far as I can

tell. The competing schools of thought seem to be:

There seem to be a couple of

different lines of thought on how to best feed pets and

livestock. For many years I have not followed what seems to

be the popular wisdom and have had good results as far as I can

tell. The competing schools of thought seem to be:

- Measure/meter the amount of food and dispense it at regular feeding times

- Keep food available at all times, and let the animal feed when hungry

We have been following the

second school of thought with the rabbits, and as far as we can tell,

it's working just fine. I have 4 and 10 year old Labradors who

have been on that method all their life and they haven't had any

problems with overeating or weight. My opinion (and it's just an

opinion based on my own observations) is that if ample food is always

available, the animals get used to that and then don't try to gorge

themselves when food is made available. I generally make an

entire 50 lb sack available to my labs in a plastic bin. When it

gets low, I buy another sack.

Dawn found that the other

school of thought is discussed a bit in the literature she read.

They also suggested feeding at evening time. The idea behind this

seems to be that most wild rabbits feed nocturnally, perhaps mostly due

to predation. I'm not sure how relevant a wild rabbit's behavior

is to a completely domesticated rabbit, but that seems to be the

conventional wisdom from some sources.

Dawn recently started

measuring how much feed our rabbits are consuming. As we were

getting started, we didn't keep track very well. We just filled

the feeders

and let them go. Our results for the first measured week with

feeders constantly full (by volume, we'll get some weights later):

- Doe: 11 cups of feed consumption per week

- Bucks: 8 cups of feed consumption per week

The doe does seem to be

packing on more weight than the bucks, but the does seem to be heavier

for most breeds according to the reference material we've looked

at. Our purchased buck is just reaching maturity, while our

donated buck and doe have several weeks head start and have been mature

for a couple of weeks now. We don't have numbers on how much feed

the rabbits consume while young and growing, but plan to get that once

we have a litter. As we go along, we'll start keeping better

track of how much feed they consume from "birth to oven".

Along with our initial

experience with our first buck using his food dish as a litter box,

Dawn has observed that it helps to keep the feeder suspended off the

cage bottom. If it is kept raised a few inches from the cage

floor, it helps prevent them from soiling the feed. I'm not sure

why rabbits seem to defecate in their food source, but they seem to do

it quite readily. At first I thought maybe they were just

depositing cecal pellets there, but it doesn't

seem to be so. Dawn has also suggested that keeping the feeder on

the inner walls of the cage keeps rain and dew from dampening the food,

thereby preventing waste.

As for supplementing store

bought feed, we have been feeding them some purchased timothy hay as it

is recemmended for proper nutrition in most of the references we have

found (and my local vet made just this one recommendation when

asked). We have also been feeding them regular doses of fresh

grass from the yard (mostly bahia grass) which they really seem to

enjoy. When allowed to graze in the yard, they seem to really go

for the clover. They also absolutely love eating fresh oak

leaves. I'm not sure it's too healthy for them (I haven't seen it

come up on any toxic plant lists) but they will instantly devour any

fresh oak leaves or twigs we give them.

We plan to experiment with

different amounts of grass and forage as feed and try to keep track of

how much it reduces their dependence on traditional rabbit

pellets. We also would like to try a portable "rabbit tractor"

where they can forage within a pen. I'm not sure how well this

will work out, but it is something we intend to try. It will be

interesting trying to build a rabbit proof portable pen that can be

wheeled around to the most tasty forage in the yard.

Along with regular feeding,

it's also important to provide sticks, twigs, etc. for them to chew

on. It's important for proper dental maintenance, but it also

gives the rabbit something to play with; they can be surprisingly

playful and inquisitive. They seem to eat greener twigs pretty

quickly, but dried twigs and branches are better for them to maintain

their teeth. Just be careful not to provide a branch that could

be toxic. Walnut and a few fruit tree branches can be toxic,

along with others.

All in all, we've just been

having fun learning as we go and completely understand that we are

amateurs at this so far. As time goes on, we'll get a better feel

for what works and what doesn't. We're looking forward to

learning all about breeding them since we believe our doe has reached

maturity. Most of all, this has been an enjoyable learning

experience that we hope will provide some meat for the table and

perhaps a measure of self sufficiency.

Shannon and Dawn

will be sharing their experiences with raising meat rabbits on Tuesday

afternoons. They homestead on three acres in Louisiana when time off

from life and working as a sys admin permits.

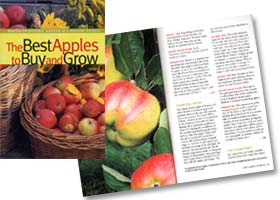

The

Best Apples to Buy and Grow is one of those small,

beautifully illustrated books that clearly can't find room within its

pages to tell the reader everything. But, in this case at least,

it does a great job providing depth in its niche --- helping readers

choose from among the 1,513 apple varieties currently available

commercially in the U.S.

The

Best Apples to Buy and Grow is one of those small,

beautifully illustrated books that clearly can't find room within its

pages to tell the reader everything. But, in this case at least,

it does a great job providing depth in its niche --- helping readers

choose from among the 1,513 apple varieties currently available

commercially in the U.S.

Half of the book

introduces the top variety choices of four apple experts, summarized by

the Brooklyn Botanic Garden. By picking the brains of well-known

pomologists from around the U.S. (Virginia, New York, Arkansas, and

Oregon), the book's "60 Great Apples" are likely to steer most readers

toward locally adapted varieties. (I'll make a later post with

the types of apples that piqued my fancy from this and the other

orchard books I've been perusing lately.)

The other half of the

book consists of basic information you could find in many other

sources, but some tidbits did stand out. Several apple varieties

tend to lose points among modern growers for a tendency toward biennial

bearing (having a huge crop one year then taking the second year off),

but the authors point out that this can be a good pest resistance

strategy. The grafting section also included some simple good

advice --- cut scionwood in January or February, graft in February or

March, and set out the new trees after the last freeze. (I'll be

marking my calendar for this winter's experiments.)

All told, The

Best Apples to Buy and Grow is a fun read, and I highly

recommend hunting it down in your local library. I'll be

returning my copy to its original owner, though --- a few pages of

notes summed up all of the useful information I'll need to remember.

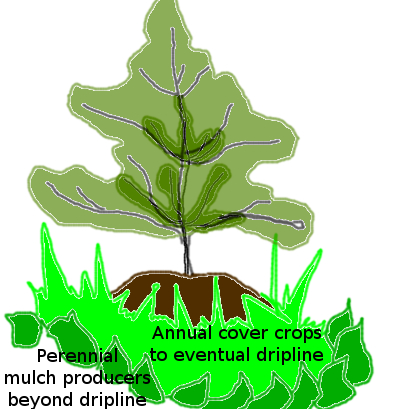

The first chapter of

Phillips' The Holistic Orchard introduces the author's

philosophy of creating a healthy ecosystem holistically rather than

fighting to mask the symptoms with allopathic treatments (such as using

organic, but still harmful, sprays). His goal, he writes is "not

so much to destroy problems as to create health."

So, how do you start an

orchard so healthy it can be maintained with simple mulching and foliar

sprays of fish oil? First, you need to realize that fruit trees

and berry bushes thrive in a forest edge habitat, where the soil is

dominated by fungi

over bacteria at a ratio of roughly 10:1.

To get there, Phillips first

tills, then plants a cover crop of red or crimson clover. These two species

have an affinity for mycorrhizal fungi, which will stand the trees in

good stead a year later when they finally grace the soil.

To get there, Phillips first

tills, then plants a cover crop of red or crimson clover. These two species

have an affinity for mycorrhizal fungi, which will stand the trees in

good stead a year later when they finally grace the soil.

Phillips' cover crops go

into the ground in the fall, and they grow for a solid year before

being scythed and allowed to rot on the soil surface over the second

winter. Organic matter added to the earth from the top down is a

great way to promote beneficial soil fungi, so you definitely don't

want to till the clovers in.

Since clover is

perennial, you'll either need to fork out the roots come spring number

two, or lay down a kill mulch (cardboard topped by wood chips) the

autumn before. Either way, Phillips recommends preparing a circle

of vegetatation-free soil about four to six feet in diameter for each

future fruit tree.

Once the trees are in

place, mulch is key. Phillips swears by ramial wood chips, which

come from deciduous twigs and branches less than 2.5 inches in

diameter, meaning that the C:N ratio is quite low (30:1). For

those of us who can't be as discerning, I think it's nearly as good to

just let any kind of deciduous wood chips rot for a couple of years

before using.

Haphazard

mulching is handy to

keeping the diversity of soil life high, so Phillips lays down heavy

mulches on only one side of the tree each year, using spoiled hay and

straw in spots around producing trees for even more diversity.

Right up against the trunk, a three to four inch deep layer of pea

stone extending a foot or so out from the tree in all directions keeps

the young trees dry.

Haphazard

mulching is handy to

keeping the diversity of soil life high, so Phillips lays down heavy

mulches on only one side of the tree each year, using spoiled hay and

straw in spots around producing trees for even more diversity.

Right up against the trunk, a three to four inch deep layer of pea

stone extending a foot or so out from the tree in all directions keeps

the young trees dry.

I'm ashamed to say that

I've never been able to think a year or two in advance to fully prepare

the soil for perennials using cover crops, but this first chapter of The

Holistic Orchard

has inspired me to try prepping areas I want to house perennials in

2014. I think I'll tweak Phillips' technique a bit, though, since

I'm working on a backyard scale rather than running a commercial

orchard --- kill mulches always trump tilling in my book. But

since I'm starting in the fall, that means I won't be able to plant

until the spring, so I'll probably run back

to back buckwheat cover crops, then either put in my perennials in

fall of 2013 or plant clover then to give the soil another year of

fertility building.

I'm curious to hear from

others. How have you prepped the soil for fruit trees, and did

your technique bear fruit? Are you a believer in simply replacing

chemical sprays with organic alternatives that do the same thing, or do

you try to garden holistically?

I'm curious to hear from

others. How have you prepped the soil for fruit trees, and did

your technique bear fruit? Are you a believer in simply replacing

chemical sprays with organic alternatives that do the same thing, or do

you try to garden holistically?

We'll be discussing

chapter two next Wednesday, and I have to admit I've read ahead and

find that section equally inspiring. I hope you'll join the book

club and read along!

Anna heard about an upcoming

animal swap and we realized our chicken carrier cage is nowhere to be

found.

It only took a few minutes to

cut an opening in this metal foot locker.

We don't have any livestock

to trade, but we have high hopes of bringing home one or two laying

hens so we can get more eggs this winter.

One of the reasons I'm

excited to experiment with a high

density apple planting

is because it will allow me to try out more varieties. When

grafted onto standard or semistandard  rootstocks, apples require a

lot of space, and I only have room for four in our forest garden.

Being able to test several more varieties to see how they handle our

microclimate and disease pressure will be very valuable (and tasty).

rootstocks, apples require a

lot of space, and I only have room for four in our forest garden.

Being able to test several more varieties to see how they handle our

microclimate and disease pressure will be very valuable (and tasty).

On the other hand, I've

learned the hard way that it's not even worth trying apple varieties on

our homestead if they aren't resistant to cedar

apple rust.

Your neck of the woods may have its own apple Achilles heel, but the

following varieties went onto my short list due to their disease

resistance for my area:

| Variety |

Scab |

Cedar apple

rust |

Mildew |

Fire blight |

Ripens |

Notes |

| Akane |

Dessert, cooking, or drying;

precocious; broad disease resistance |

|||||

| Arkansas Black |

Resistant (or susceptible) |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Late fall |

Storage apple; best

cooked; blooms avoids frost |

| Arlet |

August to September |

Disease tolerant in humid

climates |

||||

| Ashmead's Kernel |

October |

Dessert; stores until March;

relatively disease tolerant |

||||

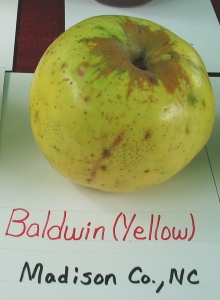

| Baldwin |

Susceptible |

Very resistant |

September to October |

Good for dessert, cooking, or

cider; stores well; needs pollinator; biennial |

||

| Belle de Boskoop |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

September |

Dessert or cooking; needs

pollinator |

| Black Limbertwig |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

October |

Dessert, cider, and cooking |

| Bramley Seedling |

Immune |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Susceptible |

October to November |

Cooking or cider; blooms avoid

frost; needs pollinator; stores well |

| Chestnut Crabapple |

Small but sweet; disease

resistant |

|||||

| Duchess of Oldenburg |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

Precocious; best for cooking |

|

| Empire |

Susceptible |

More resistant |

More resistant |

More resistant |

October |

Good for dessert or cider; keeps

3 to 5 months |

| Enterprise |

Immune |

More resistant |

More resistant |

Most resistant |

September to October |

Dessert; stores up to 6 months;

blooms avoid frost |

| Fireside |

Susceptible |

Resistant |

? |

Susceptible |

September |

Dessert |

| Florina |

Most resistant |

More resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

October |

|

| Freedom |

Immune |

Immune |

Resistant |

Resistant |

October |

Stores until January; all-purpose |

| Grime's Golden |

? |

Resistant |

? |

Resistant |

September to October |

All-purpose; stores until January;

best flavor in Mid-Atlantic |

| Hardy Cumberland |

Resistant |

October |

Good in southern Appalachians;

stores well |

|||

| Hudson's Golden Gem |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

September |

Tastes like Bosc pears; good for

dessert, cooking, or cider |

| Jonathan |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Susceptible |

October |

Dessert, cooking, and cider;

poor keeper |

|

| Keepsake |

? |

Resistant |

? |

Resistant |

October |

Dessert; good keeper; slow to

bear |

| Kidd's Orange Red |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

September to October |

Good flavor of Cox's Orange

Pippin, but less temperamental; precocious |

|

| King David |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Moderately susceptible or

resistant |

October to November |

Dessert, cooking, or cider;

stores well; tolerant of abuse; blooms miss frosts; precocious |

| Liberty |

Immune |

Most resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

September to October |

Dessert and cooking; doesn't

store well; precocious |

| Lodi |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Moderately susceptible |

June to July |

Better keeper than Yellow

Transparent but not quite as tasty; cooking; needs pollinator |

| Mammoth Black Twig |

Resistant or susceptible |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

October |

Dessert, cooking, drying, or

cider; stores until April; blooms miss frosts |

| Myers Royal Limbertwig |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Dessert or cider |

|

| Nova Easygro |

Most resistant |

? |

Susceptible |

Somewhat resistant |

September |

|

| Novamac |

Most resistant |

More resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

September |

|

| Pixie Crunch |

Most resistant |

? |

Somewhat resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

August |

Stores for 2 months |

| Priscilla |

Immune |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

September |

Stores 2 to 3 months; easy to

grow |

| Pristine |

Immune |

Somewhat resistant or somewhat

susceptible |

More resistant |

Somewhat resistant or susceptible |

July to August |

Dessert or cooking |

| Ralls Genet |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Late |

Blooms miss frosts |

| Redfree |

Immune |

Immune |

More resistant |

More resistant |

July to August |

Stores up to two months |

| Red Limbertwig |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

All-purpose; good keeper |

|

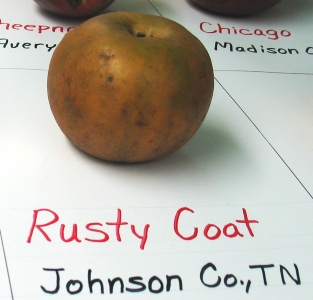

| Rustycoat |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Fall |

Tastes like Asian pear |

| Sansa |

Immune |

? |

Resistant |

Resistant |

August |

Dessert, cooking, or cider |

| Summer Rambo |

Somewhat resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

July to August |

Dessert or cooking; dependable;

needs pollinator |

| Sundance |

Most resistant |

More resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

September |

Stores up to 6 months |

| Sweet Sixteen |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

Resistant |

September to October |

Not as tasty in hot summer

areas; blooms avoid frosts; biennial if not thinned; dessert and cooking |

| William's Pride |

Immune |

Immune |

More resistant |

More resistant |

July to August |

Dessert or cooking; keeps 1

month; best in northern gardens |

| Winesap |

Susceptible |

Resistant |

Susceptible |

Resistant |

October |

Stores up to 6 months; needs

pollinator; dessert or cooking |

| Yates |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Somewhat resistant |

Resistant |

Late |

Good keeper; cider |

| Yellow Transparent |

Resistant |

Resistant |

Susceptible |

Susceptible |

June to July |

Earliest apple; dessert or

cooking; doesn't store; bears young; susceptible to late frosts |

The data for my table came from The Holistic Orchard, Grow Fruit Naturally, The Best Apples to Buy and Grow, and our favorite local apple nursery's website. The astute reader will notice that heirloom varieties (like Yellow Transparent, an old Russian apple) are mixed together with modern inventions (like Sweet Sixteen, barely older than I am). The heirloom varieties developed the hard way, standing out amid seedling apples that perished

when not cared for, while the

more recent apples have been bred with scientific knowlege of

disease-resistant genes. In the end, it doesn't really matter

where the resistance comes from, and I decided to try some out of each

category.

when not cared for, while the

more recent apples have been bred with scientific knowlege of

disease-resistant genes. In the end, it doesn't really matter

where the resistance comes from, and I decided to try some out of each

category.Of course, I also wanted to spread my harvest out throughout the year, so I ended up choosing Yellow Transparent and Pristine as early apples, Zestar (not resistant, but we wanted to try it anyway), Summer Rambo, and Sweet Sixteen for early fall, and Enterprise, Empire, Grimes Golden, and Mammoth Black Twig as late apples/keepers. In a few years, I'll probably learn that some of those apples thrive in our climate while others are losers. Then it'll be time to cut out the bad trees and go back to the drawing board to experiment with some other disease-resistant apples.

When we started thinking

about expanding our

fig planting, I

decided to do some research on figs that can grow here in zone 6 (and

even for those of you in zone 5). I'll write a later post about

frost protection; for now, I want to talk about selecting varieties

that can handle the cold best.

Before you start

thinking about frost hardy figs, though, you need to understand that

young figs of any variety are more sensitive to cold winters than

larger figs are. Depending on who you talk to, figs less than two

to five years old are likely to die back to the ground regardless of

your efforts. In addition, wet feet over the winter make a fig

more likely to  perish.

So, don't lose heart if you've planted a supposedly hardy variety and

it spends its first few years dying back and producing little fruit ---

the tree might grow out of it, especially if you provide better soil

drainage.

perish.

So, don't lose heart if you've planted a supposedly hardy variety and

it spends its first few years dying back and producing little fruit ---

the tree might grow out of it, especially if you provide better soil

drainage.

Okay, so which figs are

likely to achieve hardiness? As I searched the internet, I

discovered that fig aficionados talk about varieties you're unlikely to

find in most nurseries. In fact, you might have to join one of

the fig forums and beg for cuttings if you want to try these heirlooms.

The good news is that

fig lovers have also put a lot of effort into testing the cold

hardiness of their varieties, in one case setting out over a hundred

types of figs and letting the plants deal with a cold winter to see

which few survived. Sal (Gene strain), Marseilles vs Black, Blue

Celeste, and Hardy

Chicago were the

winners in that experiment, which had a winter low of 0 F.

Another fig grower reports that Hardy Hartford is his most cold hardy

variety, surviving -4 Fahrenheit with no winter protection.

During a winter that only got down to 10 F, the following varieties

were added to the cold hardy list:

- Florea

- Gino

- English Brown Turkey (aka Eastern Brown Turkey)

- Sweet Georg

- Adriana

- Tiny Celeste

- UCD Celeste

- 143-36

- Paradiso White (Gene Hosey strain)

- Archipel

- Lindhurst Wht

- Jurupa

Yet other sources add

the following figs to the cold hardy list:

- Brooklyn White

- Violetta

- Hanc Mathies English Brown Turkey

- LaRadek's English Brown Turkey

- Sal's EL

- Dark Portuguese

- Paradiso

- Alma

- LSU Gold

Another factor to

consider in addition to sheer cold hardiness is the fruiting nature of

the variety in question. Figs produce two crops: the breba crop

early in the season on last year's wood, and the main crop later on new

growth. We chose Chicago Hardy (aka Hardy Chicago) because it

will produce a large main crop even if it freezes to the ground during

the winter, but I'm starting to realize that a main crop that ripens in

September is never going to produce as much fruit as a fig that can

give us an especially early breba crop as well. Some sources say

that Celeste (aka Malta, Celestial, Conant, Sugar Fig, and Tennessee

Mountain Fig) can produce a heavy crop as early as June, as long as

prune sparingly and use frost protection. Stay tuned for

tomorrow's post about protecting figs over cold winters.

| This post is part of our Fig lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

There's a problem with eating

roasted figs.

Some of the precious juice

drips down onto the toaster oven tray and gets caramelized.

Apple slices underneath can

be a delicious soaking platform while making the clean up 10 times

easier.

I've been making a lot

of posts about what's in my head rather than what's on the farm because

my outside chores for October consist of weeding

and mulching the vegetable garden to prepare it for winter. A blow by blow would

be pretty boring.

But I didn't want you to

think I spent all week napping in the sun. Huckleberry does that

for us.

In addition to giving me

lots of meditation time to dream up new ideas, I enjoy autumn hours

spent weeding because they let me watch the fall colors change from day

to day on the trees...

...and on my plate.

I had a great shot of my

clothesline fall colors too, but I decided it was just too risque for

public consumption --- my underwear took up about 500 square

pixels. You'll just have to imagine the blue-gray trailer, the

peach leaves beginning to drop, my rainbow-striped towel fluttering on

the line, and a stray walnut leaf spinning through the air.

I think this is shaping

up to be my favorite autumn ever.

The

best way to push your hardiness boundaries is to provide tender

perennials like figs with a warm and dry microclimate. One grower

I know planted

his fig right under the dryer exhaust vent, with very good results, and

others recommend locating your fig on the southern side of a

house. Stone patios can grab the heat from the winter sun and

radiate it back out at night, and presumably locating a fig near a

large body of water would serve the same purpose.

The

best way to push your hardiness boundaries is to provide tender

perennials like figs with a warm and dry microclimate. One grower

I know planted

his fig right under the dryer exhaust vent, with very good results, and

others recommend locating your fig on the southern side of a

house. Stone patios can grab the heat from the winter sun and

radiate it back out at night, and presumably locating a fig near a

large body of water would serve the same purpose.

If you dry your clothes

on the line and don't have a patio, you can still get figs through zone

6 winters with a little extra effort. One option consists of

cutting the roots on one side of the tree with a shovel to allow you to

bend the whole tree down flush with the earth. You can either dig

a trench and bury the branches underground, or simply top them with

bales of straw.

The alternative we've used

involves autumn

leaves insulating the aboveground growth of the fig. My method worked

okay, but the leaves got beaten down by rain and snow, and any branches

that ended up exposed died back. This winter, I'll probably take

the advice of more experienced fig growers and tie the limbs together,

pack in leaves, then wrap the leafy insulation with a tarp or other

waterproof layer.

The alternative we've used

involves autumn

leaves insulating the aboveground growth of the fig. My method worked

okay, but the leaves got beaten down by rain and snow, and any branches

that ended up exposed died back. This winter, I'll probably take

the advice of more experienced fig growers and tie the limbs together,

pack in leaves, then wrap the leafy insulation with a tarp or other

waterproof layer.

A final option,

especially handy for those in the extreme north, is to treat your fig

as a potted plant. The fig can spend the summer outdoors, then

once it drops its leaves (usually after a light frost), you take the

plant inside to a cool basement or root cellar. Alternatively, if

you've got a warm, sunny window that's not already full of dwarf citrus, you can keep a potted fig

growing all winter by bringing it in before cold weather hits.

I'd be curious to hear

from those of you north of zone 7 who have had good luck growing

figs. Which varieties did you choose and how do

you get them through the winter? What kind of yields have you

seen?

| This post is part of our Fig lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We finally decided to give up

on these grapes today.

The fruit was okay, but

without spraying the yields are very low.

Spraying would be smelly,

expensive, and leak into the surrounding soil, an option we never

considered because we love our dirt. We instead ordered a Mars Seedless

that's been growing nicely for about a year now and should be disease

resistant enough for this area.

When I peeked up under

the hive this week, I was hoping to see the third box full of capped

honey. Instead, it looked like the bees hadn't drawn any extra

comb, and the comb that existed was pretty much empty.

With

the wingstem

nectar flow over,

the bees are reduced to scrounging through the asters and everbearing

raspberry flowers, so I decided to try again and see if they would take

sugar water now.

With

the wingstem

nectar flow over,

the bees are reduced to scrounging through the asters and everbearing

raspberry flowers, so I decided to try again and see if they would take

sugar water now.

"I don't mind if I do,"

said the bees, gulping down a pint in seven hours.

What I'm not sure about

is how much honey is in the hive at the moment. I estimated the

bees had packed away 26 pounds (one hive body full) when I did a thorough

inspection in early

September, and the third hive body looks exactly the same now as it did

then.

If the hive only has 26

pounds of honey in it, I'd need to pour 10 quarts of sugar water down

the bees' gullets before weather gets too cold for them to dehydrate

the nectar into sugar --- a tall order.

On the other hand, it's

quite possible that the bees have simply been moving honey into the

upper boxes as they slow down brood production, in which case I don't

need to feed as much. Since I can't tell the difference without

opening the hive, I'll just keep feeding as long as the bees keep

eating.

The Tractor Supply animal

swap had an impressive selection of livestock.

We ended up trading an Avian Aqua Miser plus 25

dollars for the above trio of Rhode Island Red hens.

Two full sized turkeys were

going for 50 dollars and someone had 3 dollar hens.

I'd say it was 10 times more fun than if we would've gone to the County

Fair.

I

have to admit that I've been a bit lackadaisical about managing our edible mushrooms for the last couple of years.

I

have to admit that I've been a bit lackadaisical about managing our edible mushrooms for the last couple of years.

Converting over to rafts

and totems means

that we don't get mushrooms in the summer. Our logs just bear in

the spring and fall when cool, damp weather creates natural fruiting

conditions for oysters and shiitakes.

I don't actually mind

taking an item off our summer list, though. We have plenty to eat

during the hot months, and so much to do that soaking mushroom logs

feels like a chore.

The main downside of my

new methodology is that I tend to miss about half the mushrooms when

they do appear. If you soak

a mushroom log, you

know it's going to fruit (or not) within a week, so you can schedule

the  day to check back.

However, rafts and totems fruit when they feel like it, and there's

really only a window of one day when the mushrooms are at their peak,

so it's easy to miss.

day to check back.

However, rafts and totems fruit when they feel like it, and there's

really only a window of one day when the mushrooms are at their peak,

so it's easy to miss.

That's how I came to

overlook the first fruiting of our magnolia

stump. It's

along a seldom-visited edge of our core homestead, and I didn't see the

oysters until they'd shriveled up and gone by.

The

mushroom totems along the driveway, though, caught my eye on

Friday when they bore their second flush of fruit, and that reminded me

to check the totems behind the trailer yesterday. Quite a

haul! We stir-fried Friday's mushrooms, but I'm open to

suggestions for how we'll eat up the weekend's bounty. What are

your favorite oyster mushroom recipes?

Hoses are drained. Green peppers picked.

We're mostly ready and looking forward to another peaceful winter.

It's likely to frost at

some point this week, so I went ahead and picked everything

sensitive. Green peppers are a giveaway item, while yellow and

red peppers will sit in the fridge and go in the next couple of weeks'

salads. I cooked up a huge basket of sweet corn and socked away a

gallon of decobbed kernels in the freezer. And the tomatoes I

roasted with carrots, onions, and garlic, then whizzed up in the food

processor to create a cream of tomato and basil soup.

What's left? Lots

of lettuce and leafy

greens, all of which

can be eaten at our leisure. Potatoes and carrots need to be dug

this week, and I'll probably freeze some broccoli since the heads are

expanding faster than we can eat them. Soon after that, the first

cabbage will be ready, right about the time we'll likely eat the last

of our sugar snap peas. These fall crops can all handle

temperatures down into the low twenties, so I'm hopeful we'll be eating

them for weeks to come.

What are you eating out

of your garden at the moment?

A sharp knife and some bamboo

is all it takes to make the above chicken carrier.

The picture is from AustinBushPhotography.com.

He took this a few years ago

in Northern Thailand where they take a rooster and tie him to a tree in

the forest and then try to encourage crowing. This attracts wild

chickens which make a tasty meal.

I'm officially a heating

wimp this year. I like to play fire chicken, seeing how long in

the fall I can go without any source of heat. The idea is that my

body acclimates to the cold, so if I can bear with chilly weather in

October, the same temperatures will feel warm in January.

But a cold, rainy day that

never broke 50 broke me. Monday was a very unusual day since we

had to wake up in the dark, pounding rain to get to the big city for

our dental checkups at 9 am. (No cavities for either of

us!) Honestly, I think I needed the mental boost of the fire even

more than the warmth when we straggled home that afternoon.

But a cold, rainy day that

never broke 50 broke me. Monday was a very unusual day since we

had to wake up in the dark, pounding rain to get to the big city for

our dental checkups at 9 am. (No cavities for either of

us!) Honestly, I think I needed the mental boost of the fire even

more than the warmth when we straggled home that afternoon.

I did get the fire

started with a couple of pieces of boxelder and half of a walnut round,

but then I just burned scrap lumber. Do you burn odds and ends of

two by fours that are too small to use otherwise even though they're

pine?

We decided to start Staycation

2012 this afternoon.

The above picture is for

Anna's upcoming Mother Earth News magazine article for the

February/March issue.

No...Huckleberry

didn't take this picture, it was a timer on a bale of straw thing.

Our greywater

swamp

became a much more pressing problem last week as the grasses and

clovers began to go dormant. In the summer, actively growing

vegetation pushes an astonishing amount of water from the soil up into

the

air via transpiration, but once the weather cools and plants slow down,

the ground is on a trend toward increasing wetness. While our

chicks love hunting for bugs in the greywater effluent, we stopped

going out the back door because it was just too swampy. I guess

it's time to put greywater management on the list!

After some

brainstorming, Mark and I agreed that a constructed

wetland

was the way to go. But what would it look like? I thought

you might enjoy seeing what goes through my head when I'm

thinking about a design like this:

In case you can't read

my scrawl, the big questions pertained to

lining. Should we line the wetland at all, and if so with what?

As we know from

experience, our clay soil will create a boggy spot

where the greywater comes out even without a liner. Assuming

you're not cleaning up something really toxic (in which case, a liner

is recommended to keep the toxins from leaching into the groundwater),

the only real reason to line a constructed wetland is to keep the soil

from

drying up during the summer. However, a liner does have benefits

--- it allows real wetland plants to take hold over a large area, and

can even be used to create a pool of clean water at the end of the

wetland for irrigation or frog habitat.

If we do decide to line

the wetland, there are three options:

- Purchase a pond liner. If we went for the high quality version, that would be pricey --- $266.

- Compact clay soil. Mainstream folks tend to rent mechanized compacters to mash wet clay around under pressure and create a nearly impenetrable liner.

- Gley the pond. You

can read my post about gleying

here. (Using pigs to seal a pond is a method of gleying.)

Of course you know which

option appeals to me, but our little wetland

is nowhere near big enough to make it worthwhile to raise pigs just to

seal it, and the area is at the same time too big to haul in enough

manure to gley without animals. I'm wondering how much stomping

around in boots would be required to compact the soil, and whether

chickens can be used to gley ponds. Ideas?

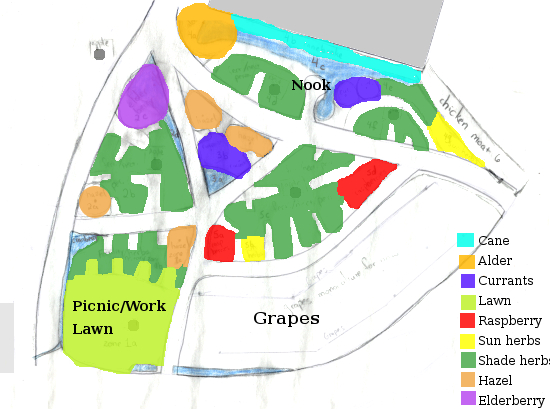

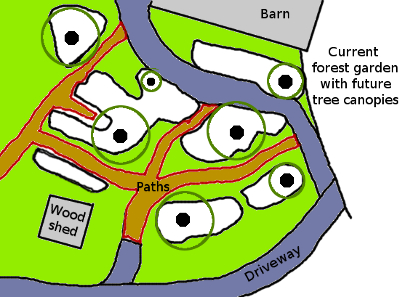

The

second chapter of The

Holistic Orchard was

all about planning an innovative orchard that suits your site. I

wish I'd read this before I drowned some trees in our soggy soil, then

reinvented the wheel to create

raised planting beds

incorporating hugelkultur just like Phillips

suggests. His notes on sun and wind are probably just what some

other beginning orchardist needs as well.

The

second chapter of The

Holistic Orchard was

all about planning an innovative orchard that suits your site. I

wish I'd read this before I drowned some trees in our soggy soil, then

reinvented the wheel to create

raised planting beds

incorporating hugelkultur just like Phillips

suggests. His notes on sun and wind are probably just what some

other beginning orchardist needs as well.

A method Phillips calls

"biological terracing" looks like it would be just right for our steep

and dry powerline cut pasture. Soil is shoveled

downhill to create a terrace with a bowl  behind it, and the bowl is

filled with wood chips to soak up moisture. I've pondered

terracing our powerline hillside (or at least building small cepas for trees), but have gotten

bogged down in deciding what will hold the steep downhill side of the

terrace from being scratched apart by chickens. Phillips'

suggestion of planting comfrey to hold the slope sounds like it might

withstand moderate abuse. (The two photos I've included are other

ideas for terracing --- click each to see the source.)

behind it, and the bowl is

filled with wood chips to soak up moisture. I've pondered

terracing our powerline hillside (or at least building small cepas for trees), but have gotten

bogged down in deciding what will hold the steep downhill side of the

terrace from being scratched apart by chickens. Phillips'

suggestion of planting comfrey to hold the slope sounds like it might

withstand moderate abuse. (The two photos I've included are other

ideas for terracing --- click each to see the source.)

Next, Phillips

introduces forest gardening, dynamic

accumulators, and nectary

plants

that attract beneficial insects. I won't write more

about that here since I've posted about each topic in depth in the

past. I was a bit disappointed that the author seemed to be

regurgitating a lot of forest gardening information from the literature

rather than telling us which techniques actually work in his orchard,

but that's my pet peeve about permaculture books in general.

Did any techniques pop out

at you from this week's reading? Or do you have a site-specific

problem Phillips didn't cover that you're wondering how to work around?

Did any techniques pop out

at you from this week's reading? Or do you have a site-specific

problem Phillips didn't cover that you're wondering how to work around?

We'll read chapter three

for next Wednesday. I know it's a lot of pages, but the first and

last parts cover information you probably already know if you've delved

into orcharding at all, so feel free to skip or skim that and just

focus on the "soil fertility" and "tree doings" sections on pages 59

through 82. I hope you'll keep reading along (and that newcomers

will feel free to join the club! We'll probably focus on this

book all through October and November, so you've got plenty of time to

hunt down a copy.)

This post is to document the

beginning date of my new Georgia Boot

phase.

The above Ariat shoes only lasted 9 months

before one started to leak.

I think the breaking point is

where the toe bends. I know I put those boots through some hard

conditions, but in my opinion they should've lasted longer for being in

the 100 dollar category.

It's a good thing my

father's alive, because otherwise he'd be rolling over in his

grave. The first Christmas after we pulled

a trailer onto our farm, he gave me and Mark

matching "Redneck Trailer Service" hats. Later, he begged me,

"Just don't built onto your trailer!" And now...I'm writing a

book about it.

My next ebook is a

response to the tiny house and build your own house movements, combined

with the voluntary simplicity movement. The

Simple Trailer Life

(or maybe The

Trailer Homestead

--- what do you think?) will suggest an even cheaper and more

environmentally friendly

method of lowering housing costs --- living in a used mobile home.

And I need your

help! First of all, any title suggestions would be much

appreciated. Second, I'm looking for some homesteaders whom I

could quote about why they wouldn't

dream of living in a trailer. I've got several great case studies

of happy trailer-dwellers already, but if you have a good story, I

wouldn't mind hearing from you about that too. (The photo above

is from Holy Scrap Hot Springs, one of our featured

trailer-dwelling couples, and you'll be hearing more from one

of our long-time readers as well.) If you're interested in

participating, just email anna@kitenet.net for more information.

This ebook is flowing

out of my fingertips like water, so hopefully I'll be able to let you

read it by the end of the year. Stay tuned!

Edited to add:

Trailersteading is now available for $1.99

on Amazon. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed

writing it!

Soil expert Dan Kittredge from

the Bionutrient Food Association was on the always fresh C-Realm

podcast yesterday.

Mr Kittredge has some

interesting things to say on nutrionally dense food crops and the

conditions and interactions that can improve soil health and vitality.

I liked his metaphor

explaining how soil acts as an external digestive system for plants not

unlike our stomachs. I learned about fungal inoculants and after a

little research we've decided to try out a product sold by Paul

Stamets that should

increase mycelium networks in our raised beds which will in turn help

to promote beneficial bacteria growth and aeration.

I thought for sure it

was going to frost Wednesday night, but my max/min

thermometer noted a low of 33 degrees. This is a bit like

what happens if the groundhog sees its shadow, but in reverse.

There's no chance of frost now for at least another week and a half, so

we get bonus days of summer.

That means I gambled

wrong on cutting

all those green peppers and baby squashes off the plants. On the other hand,

even the red raspberry plants Mom and I picked within an inch of their

lives Wednesday still ripened yet more delectable berries Thursday, and

I'm hoping sunnier days may tempt a few more figs to ripen up.

Each one of our farm years so far has had a frost right around our

average frost date of October 10, so it will be interesting to see what

else changes with an elongated fall.

Turns out I got a little

ahead of myself with yesterday's

experiment.

Spring will be a better time

to experiment with a fungal inoculant. Spores might survive over the

winter, but they'll have a better chance of thriving with higher soil

temperatures.

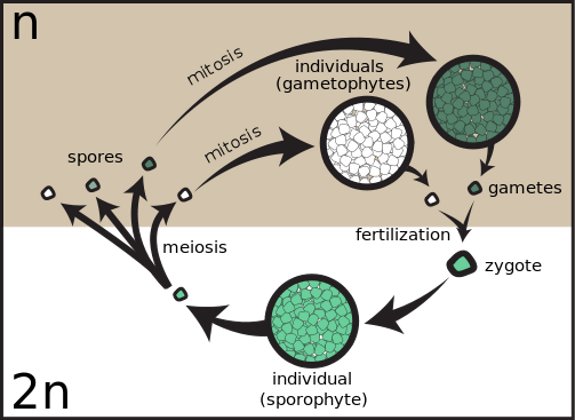

Image credit goes to

Wikipedia.

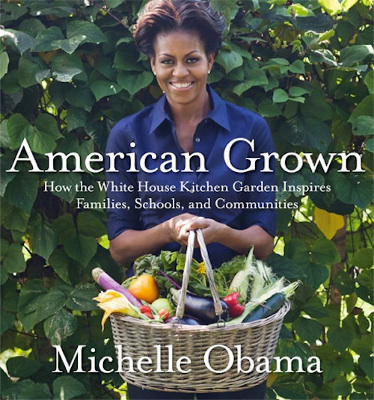

American

Grown is a

beautifully illustrated book that's worth checking out of the

library. Michelle Obama chronicles her experiences gardening for

the first time, then expands out from the White House lawn to write

about her campaign to combat childhood obesity. She also profiles

community and school gardens across the United States, and White House

chefs include some gourmet recipes at the end of the book.

American

Grown is a

beautifully illustrated book that's worth checking out of the

library. Michelle Obama chronicles her experiences gardening for

the first time, then expands out from the White House lawn to write

about her campaign to combat childhood obesity. She also profiles

community and school gardens across the United States, and White House

chefs include some gourmet recipes at the end of the book.

The positive side of American

Grown is that

it's very enthusiastic and inspirational, but the flip side of the coin

is that there's very little dirt in evidence. I wonder how many

folks who start growing vegetables because of this book will be shocked

when they don't have a huge staff to keep their garden impeccable and

when the kale comes into the kitchen with insect-nibbled holes in its

leaves. I would have felt much more comfortable recommending this

book to a gardening audience if there weren't quite so many gloved

hands and if a single picture had shown the author as anything less

than impeccably coiffed.

My second complaint is

that the book presented very few details. On the other hand, I'm

actually a bit glad Michelle Obama only gave us select tidbits since

she's clearly a raw beginner and factual errors are relatively

common. For example, the author thinks it's good she can fence

out foxes who might otherwise eat her garden, and her picture

illustrating the point that "the pawpaw is one of the few fruits native

to the United States" is actually a papaya. Luckily, since I'm

not a historian and didn't know if she got anything wrong, I thoroughly

enjoyed the section detailing the history of the White House gardens.

My conclusion is that

this book would be fun to flip through on a cold winter day along with

the seed catalogs, but it's not very nutritionally dense.

(In the interest of full

disclosure, I should say that I voted for her husband and probably will

again. On the other hand, I really detest the window-dressing

role of First Ladies, so I'm actually more negative than positive

toward this book politically.)

It's been a year since I

tried to repair

the driveway ruts with

cinder blocks.

The blocks are still in

place, but they didn't receive any truck traffic.

We've been using the golf

cart to haul stuff which doesn't seem to push the bricks any deeper,

but we've also been trying to avoid using it during really wet times.

I've written about succession

planting previously, which involves keeping the garden active by

growing more than one crop per year in the same spot. But I

realized I'd never written here about a related permaculture principle

which is one of my favorites --- stacking.

I've written about succession

planting previously, which involves keeping the garden active by

growing more than one crop per year in the same spot. But I

realized I'd never written here about a related permaculture principle

which is one of my favorites --- stacking.

When permies use the

term "stacking", they are growing more than one crop in the same space

at the same time. For example, silvopastures

can allow you to raise timber (or nuts and fruits) right on top of

livestock while forest

gardens may stack

shade-tolerant herbs and leafy greens under fruit trees.

The best way to keep competition down when stacking is to

involve multiple kingdoms. For example, mushroom

rafts under a peach

tree don't compete at all --- if anything, the fungi slowly break down

the wood into high quality humus that the peach will enjoy while the

peach maintains a damp, shady environment for the mushrooms.

Even though they're in the same kingdom, putting

my bee hive in the chicken pasture this year has been a win-win.

My favorite stacking success

has been letting our chicks free range throughout the raspberries (and

back garden) during their first month or two of life. The only

slight downside is that the chicks scratch the mulch to pieces, but

they find lots of invertebrates (and clean up any dropped berries) in

the process, all while laying down a thin coating of fertilizer.

The chicks feel safe because they're nestled amid thorny branches, and

that patch of raspberries seems to bear berries twice as large and

juicy as those on the other end of the homestead.

My favorite stacking success

has been letting our chicks free range throughout the raspberries (and

back garden) during their first month or two of life. The only

slight downside is that the chicks scratch the mulch to pieces, but

they find lots of invertebrates (and clean up any dropped berries) in

the process, all while laying down a thin coating of fertilizer.

The chicks feel safe because they're nestled amid thorny branches, and

that patch of raspberries seems to bear berries twice as large and

juicy as those on the other end of the homestead.

What's your favorite

example of stacking on your own farm?

The cinder

block stepping stones

have held up nicely over the last year.

It turned out to be a huge

improvement allowing us to step over the deep section 90 percent of the

time.

A more stable solution would

involve a large drainage pipe to let the bulk of the creek flow

through. We heard of a neighbor trying such a trick only to have it

wash out after the first big storm.

Half a year after

planting, asparagus

alley already has a

major success and a major failure under its belt.

What worked? The

seeds I saved from the one female in my "all-male"

asparagus planting

do seem to be producing nearly all male plants. Only about half

the asparagus seedlings got big enough to bloom this year, but every

flower I picked apart is full of stamens with no pistils.

On the downside, I think

locating a row of asparagus against the pasture fence wasn't the best

idea. Yes, the plants will probably provide some much-needed

summer shade for our chickens, and the chickens will likely eat up any asparagus

beetles that come to

call. But it's hard to weed the side of the bed against the

fence, so grasses seem to be taking over.

I've dug out roots and

kill-mulched once already this year and think I might have to do

something more drastic, like put some kind of root barrier between the

asparagus and the fence. Ideas?

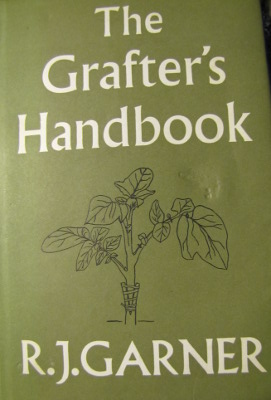

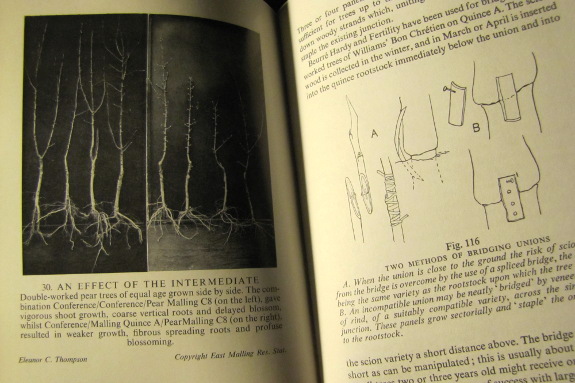

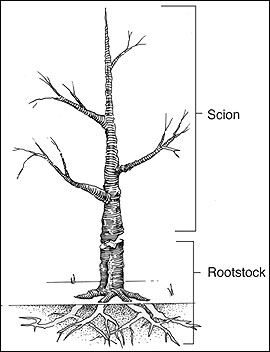

I've been looking for a book

on grafting for years, and for years I thought one didn't exist.

Most books about tree fruits have a short chapter on the topic, but I

really wanted something I could sink my teeth into. Finally, I've

found it!

I've been looking for a book

on grafting for years, and for years I thought one didn't exist.

Most books about tree fruits have a short chapter on the topic, but I

really wanted something I could sink my teeth into. Finally, I've

found it!

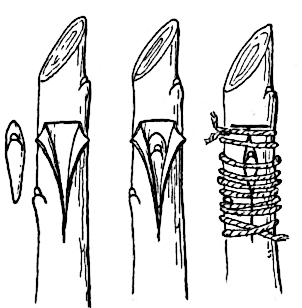

The Grafter's

Handbook is by R.J.

Garner, who worked as a scientist at the East Malling Research Station

for twenty years. In case "Malling" sounds vaguely familiar, it

should --- the research station gave its name to many of the apple

rootstocks developed there. Garner's book is a treasure trove of

hands-on experience, all summed up in easy-to-read and

scientifically-designed chapters. Garner even hand-drew over a

hundred excellent diagrams to illustrate his points (and included a few

more dozen photos to prove his grafting techniques aren't a pipe dream).

The only downside of The

Grafter's Handbook

is that it was published in England and is now out of print, which

makes it rather hard to find. I lucked out and bought a gently

used copy on Amazon for $10, but if you can hold your horses, there's a

revised

edition coming out

next year, updated by British gardener Steve Bradley. (When I

started this review, I was actually going to say that the only thing

that would make this book better is if it was lightly updated to

include modern tools, so now I almost wish I'd known about the revised

edition before I bought and read this one.)

This week (and next),

I'll be regaling you with highlights from The

Grafter's Handbook

at lunchtime. I hope it will inspire you to try your had at

grafting this winter just like it did me.

| This post is part of our Grafting lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We put a healthy layer of

aged wood chips on the Hardy

Kiwis today.

All three plants produced

plenty of new vines this year but no fruit.

The wood chips should

increase their ground protection, which might be enough to give them a

boost in the Spring growth spurt of 2013.

Last

week, I mentioned carrots on my soon-to-harvest list, and a couple of you rightly

pointed out that you don't have to harvest carrots before the

frost. In fact, carrots get sweeter if you wait to dig them until

cold weather has moved in, and some people even leave their carrots in

the ground over the winter. However, there are some reasons you

might choose to harvest your carrots early.

If you get a heavy layer

of snow that stays put all winter long, you're in the perfect spot for

overwintering carrots. Counterintuitively, the snow protects the

ground so it doesn't freeze and the garden row acts just like a good

root cellar. Those of us who garden further south, though,

experience ground freezes and thaws throughout the winter months, and

each freeze-thaw cycle pushes the carrots a bit further out of the

ground. The tops quickly freeze and then rot, so you can't count

on carrots overwintering in our area.

You can get around this

issue by mulching

the carrots heavily in the fall. However, if your

ground doesn't freeze, varmints are very likely to move into that soft,

warm bed and nibble on your roots all winter long. Which brings

me to one of the reasons I'm harvesting my carrots early this year: a

vole found the tasty carrots in one bed and started gnawing off the

bottoms, so I decided to get those roots before they're all eaten up.

The other reason I'm

harvesting now has to do with maturity of the carrots. In order

to overwinter carrots in the garden, you need to plant them at just the

right time so they're fully mature just as the ground gets too cold for

them to grow any further. This is very tricky since you never

know if autumn will be cold and dark or warm and sunny, so I tend to

just plant early (at the beginning of July) to ensure I get in a good

crop.

The downside of early

planting, though, is that good weather may mean your carrots head past

mature and into overmature before cold weather halts the plants'

growth. You can't really count on the days to harvest listed on

the seed packet to get this maturity data since  shorter days slow carrots

down, but if you pull

out small carrots throughout their time in the ground to eat and thin

the bed, you'll

clearly see when the roots stop bulking up and start heading over the

hill by splitting or rotting.

shorter days slow carrots

down, but if you pull

out small carrots throughout their time in the ground to eat and thin

the bed, you'll

clearly see when the roots stop bulking up and start heading over the

hill by splitting or rotting.

And that's why I

harvested a third of our carrots Monday. We got 23 pounds from

two beds (and I've probably already harvested another 10 or 20 pounds

from those beds over the last couple of months), which filled up my

crisper drawer. Yikes! Now I have to figure out where to

store the other three beds of carrots.

One benefit to keeping rabbits is

the wonderful and rich manure they produce. While rabbits may not

produce manure in quantities that some other livestock will produce,

the manure is all produced in a localized area, assuming they are kept

in pens/hutches. This makes it trivially easy to gather and

use. We plan to improve upon our collection area soon so that

there will be a plastic or sheet metal catchment that will direct the

manure into a basin or barrel. We have a few ideas on how to

accomplish this and it will be an interesting project we can report on

later.

One benefit to keeping rabbits is

the wonderful and rich manure they produce. While rabbits may not

produce manure in quantities that some other livestock will produce,

the manure is all produced in a localized area, assuming they are kept

in pens/hutches. This makes it trivially easy to gather and

use. We plan to improve upon our collection area soon so that

there will be a plastic or sheet metal catchment that will direct the

manure into a basin or barrel. We have a few ideas on how to

accomplish this and it will be an interesting project we can report on

later.

Many different sources claim that rabbit manure does

not need to be aged. I have heard this common wisdom for many

years, but am only just now ready to start putting it to the

test. The gardening here has been slowing down due to the

oppressive heat of mid-late summer, and most recently due to lack of

time. However, Dawn and I will soon be transplanting some citrus

trees (Satsumas, Mandarin Orange, Kumquats, Kaffir Lime) once fall is

here in full force and we will be using much of the accumulated manure

to enrich the soil around the newly transplanted trees. By the

time spring rolls around we also plan to really put the manure to the

test when the vegetable garden will be at full throttle again.

Rabbit manure is claimed to

have an excellent nutrient content. I'm no manure expert, but

I've seen several sources which list it at an average N2.4

P1.4 K0.6. We'll have to research which types of plants that

ratio is best for but I'd guess it's suitable for most.

We learned early on that we

needed to build a fence around the bottom of the cage to keep the dogs

out. They were enjoying digging in and sometimes snacking on the

manure. The barrier also keeps them from nipping and sniffing at

the fuzzy bunny feet at the bottom of the cage. When the rabbits

first showed up here the dogs were intensely curious and would stand on

hind legs to sniff at the new creatures invading their territory.

Dawn built a handy removable frame which allows easy access to the

underside of the cage while still keeping the dogs out. It may

not be obvious from the photo, but the front of the cage pulls out in

mere seconds to allow full and easy access making it easy to shovel the

manure.

We learned early on that we

needed to build a fence around the bottom of the cage to keep the dogs

out. They were enjoying digging in and sometimes snacking on the

manure. The barrier also keeps them from nipping and sniffing at

the fuzzy bunny feet at the bottom of the cage. When the rabbits

first showed up here the dogs were intensely curious and would stand on

hind legs to sniff at the new creatures invading their territory.

Dawn built a handy removable frame which allows easy access to the

underside of the cage while still keeping the dogs out. It may

not be obvious from the photo, but the front of the cage pulls out in

mere seconds to allow full and easy access making it easy to shovel the

manure.

Lately, things have been

quite busy here and we haven't been able to keep up with things as much

as would be ideal. Therefore, the manure has been accumulating

and there is some grub or maggot that has started invading our precious

store of manure on the ground. It's time for us to get busy with

the shovel and make use of the brown gold! Also in that vein, we

started contributing our rabbit posts weekly but quickly had to fall

back to every other week. Things have been quite busy for the

last couple of months on the verge of overwhelming due to unfortunate

termite discoveries, mechanical breakdowns, and a number of other

things including a needed trip out of town all piling up at once.

I certainly have more admiration of the commitment it takes for folks

to keep up with a regular blog schedule despite the busy pace that life

sometimes presents (I'm looking at Anna and Mark here...  ).

).

Shannon and Dawn

will be sharing their experiences with raising meat rabbits on Tuesday

afternoons. They homestead on three acres in Louisiana when time off

from life and working as a sys admin permits.

Our new flock of chicks like

to nibble on the leaf of an oilseed

radish plant.

The last group didn't seem

interested.

I'm guessing it's more of a

palette cleanser than a full blown snack.

Even though we haven't

had a frost yet, weird microclimate effects resulted in homegrown ice

Tuesday morning. I'd let a little rainwater accumulate in the

wheelbarrow, and the metal dissipated heat in such a way that a low of

34 resulted in a skim of ice. Strange, huh?

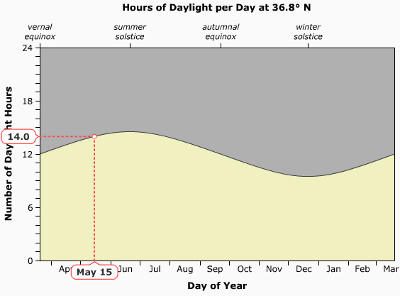

Meanwhile, the sun has

drifted low

enough in the sky that we don't see light in our core homestead

until mid-morning. Although the north-facing exposure of our

plateau makes me envious of our neighbor's sun, it does provide some

dramatic lighting.

Do you think we'll make

it to Halloween without a frost?

Those

of you who read chapter three of The

Holistic Orchard

with me this week

will probably feel like you were drinking from a fire hose. The

section

took me days to digest and I suspect I'll be trying out Phillips'

techniques for the next several years. Feel free to comment about

other parts of the chapter (of which there were many), but I want to

focus my post on soil health this week.

Those

of you who read chapter three of The

Holistic Orchard

with me this week

will probably feel like you were drinking from a fire hose. The

section

took me days to digest and I suspect I'll be trying out Phillips'

techniques for the next several years. Feel free to comment about

other parts of the chapter (of which there were many), but I want to

focus my post on soil health this week.

It's very handy to read

this chapter with soil test results in hand. I

didn't actually test my orchard soil last winter, but I have test

results from the back garden, which started with the same

type of soil,

even if it has been treated slightly differently over the years.

Here are the relevant portions of the test results:

| pH | 7.3 |

| % OM | 15 |

| P (ppm) | 556 |

| K (ppm) | 615 |

| Ca (ppm) | 6801 |

| Mg (ppm) | 926 |

| CEC | 56 |

| % Sat. K | 3.7 |

| % Sat. Mg | 17.6 |

| % Sat. Ca | 78.8 |

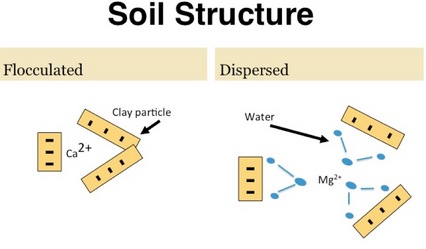

Phillips follows an

Albrecht-like ratio approach to soil health, focusing on the relative

(rather than absolute) amounts of nutrients. When I got my

results back for the garden, all of the cations were listed as "very

high", so I figured I was fine. But Phillips notes that if

there's too much magnesium (Mg) in relation to the calcium (Ca) in the

soil (for example), plants will accidentally take up magnesium while

looking for calcium and may end up deficient in the latter. In

addition, he points out that calcium tends to spread soil apart, which

can be handy for drainage and aeration in clay

soil, while magnesium pulls soil particles together (useful in

sand, but not elsewhere).

The optimal Ca:Mg ratio

(compared using the percent of base saturation figures, not the

absolute ppm figures) is 5:1 for sandy soil and 7:1 for clay. As

you can see, my ratio is 4.5:1, meaning that some of my drainage issues

might be improved by boosting calcium. However, since my pH is

already too high, I don't want to just add lime, so I'll need to look

into gypsum, which increases calcium content in soil without sweetening

the ground.

The optimal Ca:Mg ratio

(compared using the percent of base saturation figures, not the

absolute ppm figures) is 5:1 for sandy soil and 7:1 for clay. As

you can see, my ratio is 4.5:1, meaning that some of my drainage issues

might be improved by boosting calcium. However, since my pH is

already too high, I don't want to just add lime, so I'll need to look

into gypsum, which increases calcium content in soil without sweetening

the ground.

Similarly, you want to

consider the ratio of phosphorus (P) to potassium (K). Phillips

recommends P:K values of 2:1 to produce the most nutrient-dense fruits,

although 1:1 is okay in young orchards. My P:K value of 0.9:1 is

typical and signifies a need to boost phosphorus levels without

increasing the soil's supply of poassium. I'm going to have to do

some research into phosphate amendments to see which ones won't raise

our pH, but Phillips lists black rock phosphate, colloidal phosphate,

Tennessee brown phosphate, bonemeal, and bone char as possibilities.

If your head's awhirl

with numbers, here are some non-numeric soil factors to consider.

As I've mentioned previously, the goal in orchard soils is to boost

fungi at the expense of bacteria, which Phillips explains results in

more nitrogen being available in the form of ammonia.

Bacterially-dominated soils tend to have nitrogen in the form of

nitrates, which  results in happy-looking trees and big fruits,

but low nutrient density and flavor, along with more susceptability to

disease. Phillips recommends keeping your soil fungally-dominated

by making special compost for the orchard out of deciduous wood chips

slow-composted with animal manures.

results in happy-looking trees and big fruits,

but low nutrient density and flavor, along with more susceptability to

disease. Phillips recommends keeping your soil fungally-dominated

by making special compost for the orchard out of deciduous wood chips

slow-composted with animal manures.

When should you apply

that compost? I've always thought that early spring was the best

time, but Phillips gets more scientific. He explains that the

white feeder roots that suck up nutrients are even more ephemeral than

leaves --- they generally only live 14 to 60 days before dying

back. Trees produce multiple flushes of feeder roots throughout

the year, generally during periods when growth on top of the tree has

slowed, and if you time your compost applications to match root growth

periods, you'll get more nutrients to the tree. Trees focus on

blooms in early spring, roots in mid spring, leaves in early summer,

and roots in late summer and fall. Cutting herbaceous plants

under the tree canopy (like grass or comfrey) during peak root growth

can help feed your tree at just the right time, and so can spreading

compost in autumn when half of the leaves have fallen. Meanwhile,

a heavy mulch in the fall can keep the roots growing later into the

winter, and can also muffle spring warmth so trees bloom up to ten days

later and miss fruit-killing freezes.

If you can handle

another eye-opening chapter, we'll read chapter 4 "Orchard dynamics"

for next Wednesday. Those new to the club might want to check out

previous chapters on beginning

a holistic orchard

and techniques

for designing a holistic orchard. And, as always, I'm

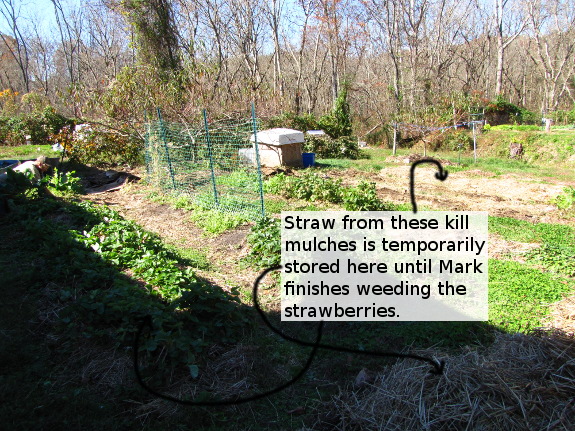

looking forward to hearing your thoughts on this fascinating subject.