archives for 09/2012

Mark and I went to the

courthouse Thursday to research a property that's one possibility for

the Annex. (One of these days

I'll make a real post about the Annex idea, but our dream is still

evolving and I don't want to tie it down yet.) Our title

search turned up a

disappointing document --- an oil and gas lease from 2003.

Lost mineral rights are

one of the main reasons to perform a title search. As a

landowner, you can sell some of your property rights while still living

on and farming your land, and those lost rights don't come back when

the property is passed on to another owner. In Appalachia,

selling mineral rights is common since many folks are living very close

to the financial edge, so a few thousand dollars now and a few hundred

every year from now on sounds good even if it means your well might be

polluted, your house might cave in, and strangers can tromp across your

land at will.

In our case, it's

possible the lease has expired --- I'm waiting until the holiday

weekend is over to hunt down that data. According to the contract

I read, the gas company needed to either start drilling or start paying

the landowner a certain amount within five years, and there's no sign

of a well on the property, so we might get lucky and not have to deal

with the issue.

But if the mineral

rights are no longer attached to the land, Mark and I will be faced

with a hard decision. This property is within easy walking

distance (unlike

another one we've considered), has lots of road frontage (making it

easy to hold public events there), and is south-facing. There are

also several acres currently being managed as hayfields, so it would be

relatively painless to install our dream orchard and pasture.

Finally, the property is assessed at $600 per acre, which is right up

my skin-flinty alley. (That's exactly what I paid for our current

ugly duckling farm.)

On the con side, the

soil is terrible (which I consider more of an interesting puzzle than a

real disadvantage) and there's no water. And then there's the

potential deal-breaker --- the lost mineral rights. So here's my

question for thoughtful readers --- would you ever consider buying a

piece of land without the mineral rights? If so, how would the

lost rights impact your financial decision?

(As a side note, the photos have nothing to do with this post, as you probably

guessed. Mark and I celebrated Labor Day on Friday by inviting

Mom over and we had a lovely time watching a Barred Owl, picking stick

tight flowers, and hanging out on the porch.)

Back in the early 2000's a

person could dump their trash around here during normal working hours,

and if they were so inclined take home a discarded lawn mower, give it

a little TLC, and feel good about recycling the old fashioned way.

It's different now.

Scavenging is not only discouraged, but it's treated as criminal

behavior. I'm not sure what the fine or jail time might be, but each

station now has an attendant to keep an eye out for scavengers.

I'm guessing the cost of

those attendants is what forced the reduced hours of operation. A major

drag when you drive all the way there and realize they closed at noon,

which is the main reason I took this picture. It helps that our new

helper has a permit to use multiple county locations, but still

requires some basic knowledge of these odd times.

Last

week, I wrote that our first

homegrown fig was good, but not sensational. Roasting the next

four figs instead of eating them raw definitely popped them up into the

delectable category, though, which started me thinking (again) about

fig propagation.

Last

week, I wrote that our first

homegrown fig was good, but not sensational. Roasting the next

four figs instead of eating them raw definitely popped them up into the

delectable category, though, which started me thinking (again) about

fig propagation.

In our climate, a fig

"tree" is never going to be much more than a bush. Any branches I

don't protect

over the winter die

back, so the best case scenario is that our fig will expand upwards

from three foot tall trunks each spring. Since figs set fruit a

few at a time over a long season, that means our little fig bush will

be giving us four figs here and six figs there for a month or two,

which is clearly not going to be enough now that Mark and I have tasted

these homegrown fruits in their full glory.

The

good news is that figs have turned out to be the most disease- and

insect-resistant fruits (tied with strawberries and brambles) in our

garden, so installing more won't require much effort after the initial

planting. In fact, I'd read that figs are relatively easy to

propagate from cuttings, so I half-heartedly tried a few hardwood

cuttings this spring. (If I'd known what the roasted fruits

tasted like, I would have put in a bit more effort.) While

pruning, I snipped off a few young branches and inserted them into a

pot, covering the top with a bag to hold in moisture. The

cuttings leafed out, but I think I removed the bag too soon because the

greenery ended up dying back and the figs petering out.

The

good news is that figs have turned out to be the most disease- and

insect-resistant fruits (tied with strawberries and brambles) in our

garden, so installing more won't require much effort after the initial

planting. In fact, I'd read that figs are relatively easy to

propagate from cuttings, so I half-heartedly tried a few hardwood

cuttings this spring. (If I'd known what the roasted fruits

tasted like, I would have put in a bit more effort.) While

pruning, I snipped off a few young branches and inserted them into a

pot, covering the top with a bag to hold in moisture. The

cuttings leafed out, but I think I removed the bag too soon because the

greenery ended up dying back and the figs petering out.

I'm curious to hear from

those of you who have successfully propagated figs. Did you use

hardwood or softwood cuttings? In the garden or in pots?

During what time of year? There's a plenitude of information

about fig propagation on the internet, but as usual, I'm looking for

the lowest tech solution possible, even if the success rate is only 20%

--- we've got plenty of scionwood to play with, but limited time during

the growing season.

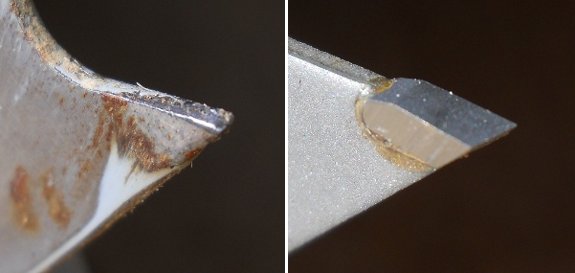

I think the penny only stayed

in place for a few days, the picture on the right is from today

compared to the left one which is from last Sunday with the penny

installed for fighting tomato blight.

The plant still has some

blight, but the fruit looks healthy.

Maybe a modified paper clip

would be strong enough to hold it in place?

Mark and I don't

celebrate our anniversaries, but I always try to take an hour to bond

with the farm on our move-in date. This week marks the beginning

of the seventh year we've spent here, and the changes are more visible

than ever before.

Although Bradley's hard

work dragging our infrastructure out of the trailer trash category is

the most obvious change photographically, what I find more significant

is that our tranquility levels are at an all-time high. I'm

tempted to explain that mood away by saying we're mostly caught up with

seasonal farm chores, but the truth is we're at about the same place we

were in previous years. The difference is one of attitude.

Previously, glancing at

a blighted tomato plant would send me into a tailspin, but this year

I'm starting to realize that we can manage the blight and still harvest

fruits well into the fall. True, constant mulching has lowered

the weeding pressure, but I think part of my contentment with the 2012

garden comes from realizing that a certain level of weeds won't take

over and can simply be ignored.

Meanwhile, we're looking

forward to another winter like the last one, when we focus on creative

pursuits instead of struggling to catch up on all the tasks we didn't

complete over the previous year. While there are always projects

on the back burner, the most pressing improvements are already in

place, and Mark and I are both learning to quash our greed for

expansion in favor of time for tranquility.

Which is all a long way

of saying that I'm able to look at last year's

anniversary post and

laugh at who I was then. (The pictures are worth a gander,

though, since they sum up the changes in our farm over the years quite

succinctly.) Thank you, farm, for helping me grow along with my

vegetables!

The

Humanure Handbook is

another book that epitomizes self-publishing. There are some

flaws here and there --- rants that will turn 80% of the audience off

and scattered trains of thought --- but the positives far outweigh the

negatives. Instead of producing a book watered down

for the masses,

Joseph Jenkins has distilled his passion for composting toilets into

250 pages of essential reading for the serious humanure advocate.

(Plus, there are fun cartoons.)

The

Humanure Handbook is

another book that epitomizes self-publishing. There are some

flaws here and there --- rants that will turn 80% of the audience off

and scattered trains of thought --- but the positives far outweigh the

negatives. Instead of producing a book watered down

for the masses,

Joseph Jenkins has distilled his passion for composting toilets into

250 pages of essential reading for the serious humanure advocate.

(Plus, there are fun cartoons.)

Due to our book club Wednesdays

and popular meat

rabbit Tuesdays, my

humanure lunchtime series is going to be scattered across the next two

weeks. That gives you plenty of time to pick up a copy and read

along...especially since you can download a

digital version entirely free. Stay tuned to learn

why we don't compost our humanure yet and what kind of system we'd like

to use if and when we do.

| This post is part of our The Humanure Handbook lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We've been having problems

with our roof leaking ever since someone gave us this trailer about 6

years ago.

I can't count how many times

I "fixed" a leak with roofing tar only to have it come back in a few

years.

The new trailer roof project

will not only take care of that problem but will cut back on wood

burned and split with the extra insulation we plan to install.

Edited to add:

Learn more about insulating and improving the efficiency of a mobile

home in Trailersteading. Now available on Amazon.

Somehow in the rush of

early June, I seem to have forgotten to post about the world's largest

grub, found by Bradley in the horse

manure as he

shoveled the biomass into buckets to be transported to our worm

bin. While I

do exaggerate slightly, the grub Bradley found was significantly larger

than a June bug larva, and we took the time to toss it in a flower pot

in hopes of learning what the plump youngster would turn into.

Saturday,

I decided to find out whether there was any life left in my fig cuttings,

so I dumped out the contents of that pot. And broke open a

fist-sized ball of dirt that housed a pupating beetle! The insect

was even larger than it had appeared on last viewing, so I carefully

fit its pupal chamber back together and refilled the pot, hoping the

tween will manage to make it to adulthood despite my poking and

prodding.

Saturday,

I decided to find out whether there was any life left in my fig cuttings,

so I dumped out the contents of that pot. And broke open a

fist-sized ball of dirt that housed a pupating beetle! The insect

was even larger than it had appeared on last viewing, so I carefully

fit its pupal chamber back together and refilled the pot, hoping the

tween will manage to make it to adulthood despite my poking and

prodding.

Mark's original idea

after seeing the size of the grub was to raise the species for chicken

feed, but I suspect the experiment wouldn't really work out. Stag

beetles usually spend several years in the larval stage, which would

make propagating them a slow affair, despite the amount of nutrition

each beetle would provide for our flock.

All utilitarian reasons

aside, we're itching to see the adult version of this hefty

critter. I suspect the stag beetle it turns into will be

awe-inspiring.

Before

we could actually bring any rabbits home, we had to build a hutch. I've

had some ideas in my head for how to

construct one, but, as things usually go, we ended up building the hutch

based on the materials we had at hand.

Before

we could actually bring any rabbits home, we had to build a hutch. I've

had some ideas in my head for how to

construct one, but, as things usually go, we ended up building the hutch

based on the materials we had at hand.

Dawn had

found two shed doors on the side of the road...and that ended up

determining the dimensions of the hutch we built. We used the shed

doors as the roof, and we'll later cover these with some tin for

longevity.

The hutch is approximately 6 feet by 7 feet, and

it's quartered into four separate spaces of roughly 3 feet by 3.5

feet. The hardware cloth I purchased was 2 feet tall, so that

ended up being the vertical dimension of the living area.

Dawn had also found some scrap 2x4s and plywood that we were able to

press into service for the hutch. The plywood became doors, and 2x4s

became the frame. I

purchased a few more 2x4s and two 2x6s at the local supply house. The

end product ended up being a quite robust hutch that stands about 6

feet tall, with a footprint of about 6x7.

Sorry about the quality of

the photo, it was about 9:30 at night when we

finished the hutch. We used a 2x6

across the lower support so that it will hold up a bit better over

time. The uprights are 2x4s, the roof is 1/2 inch plywood, and the

hardware cloth is 1/2 inch in order to allow the pellets to drop

through.

One of the major goals of raising rabbits here will be

to use the manure in the garden. We have very poor soil, so

anything we can add to it will greatly benefit my plants.

All in

all, I think the hutch cost us under $100 in material. Considering we

should be able to get many litters of rabbits out of it, the structure

will eventually pay for itself, I hope.

Shannon and Dawn will be sharing their experiences with raising meat rabbits on Tuesday afternoons. They homestead on three acres in Louisiana when time off from life and working as a sys admin permits.

Big, big, really big sweet

potatoes this year, bigger than those big

ones from 2010.

In part due to having almost

zero deer damage this year.

We actually might have a few

extra that will need to find a home.

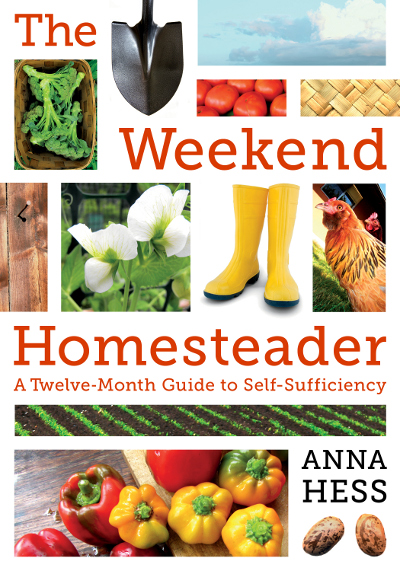

When I posted last week about

the first

copies of my book arriving, I was too excited to give

you any details. Now that I've calmed down a bit, I should start

with the semi-bad news --- you're going to have to wait longer than I'd

originally thought to see The

Weekend Homesteader

in bookstores (and in your mailbox). My publisher decided to push

the release date back to November 13 to give them time to get some buzz

going, and to take advantage of holiday sales.

When I posted last week about

the first

copies of my book arriving, I was too excited to give

you any details. Now that I've calmed down a bit, I should start

with the semi-bad news --- you're going to have to wait longer than I'd

originally thought to see The

Weekend Homesteader

in bookstores (and in your mailbox). My publisher decided to push

the release date back to November 13 to give them time to get some buzz

going, and to take advantage of holiday sales.

Here's the good news ---

some of you may not have to wait. My publicist is willing to send

out some advance copies of the book for bloggers to review and/or give

away. I'm not sure how many books

that offer encompasses, but I figure it can't hurt to send him

information about any of my readers who are interested in reviewing The Weekend Homesteader on

their blog. Just email me

the URL of your blog and any relevant statistics that will make you

stand out from the pack, and I'll pass the information on to my

publisher ASAP. Thanks for your interest!

The second chunk of Radical

Homemakers continued

the

historical journey begun in the first two chapters, but I'd like to cut to the

chase and instead discuss Hayes' conclusions. She wrote that

three "homewreckers" are responsible for many of the ills in modern

American society: "the compulsion to overwork, the reckless pursuit of

affluence, and the credo of individualism."

The second chunk of Radical

Homemakers continued

the

historical journey begun in the first two chapters, but I'd like to cut to the

chase and instead discuss Hayes' conclusions. She wrote that

three "homewreckers" are responsible for many of the ills in modern

American society: "the compulsion to overwork, the reckless pursuit of

affluence, and the credo of individualism."

In my opinion,

overworking and trying to get rich are closely related topics, and I've

discussed them both in some depth before. For example, Hayes

agrees with others that income

does not necessarily equate to happiness, and adds that despite the

price tag attached to renewable energy, poor people in general tread

more lightly on the earth. If you haven't read about and thought

this issue to death previously, I definitely recommend you look through

Hayes' data to see if it speaks to you.

Although I agree with

her about the problematic American work ethic, the most

thought-provoking part of Hayes' argument came at the very end.

The dream household for a modern American, asserts Hayes, is large

enough to allow each family member to hide away with a television in

his or her own room, spending little time interacting with the rest of

the family or community. She relates that only seven percent of

American families spend more than half an hour at family dinners and

that the average American couple has only twelve minutes a day to

converse. As a nation, we are not only pursuing money, but also

independent privacy at the expense of a society centered around

skill-learning and social-capital-earning.

Mark and I are above

average when it comes to building the health of our two-person

household, but we still struggle with creating an

interdependent community (one of our big goals for

the next decade). I'd be curious to hear which of these

homewreckers you find most troublesome in your own life, and ---

zooming back out to the larger picture --- I hope you'll chime in on

whether you agree with Hayes' setup of the problem. There were a

lot  of other things to think

about in these two chapters as well, so feel free to bring up points

I've skipped here.

of other things to think

about in these two chapters as well, so feel free to bring up points

I've skipped here.

We'll be discussing

"Meet the Radical Homemakers" and chapter five next Wednesday, which

will start to bring us back out of the land of theory. (If you

get sick of pure philosophy the way I often do, this might be a good

place for you to start the book.) Newcomers are always welcome to

join the club!

The

Weekend Homesteader is now

in print! (Your copy probably still won't arrive for a couple of

months though.)

We've been hauling in enough

horse manure to fill all 3 new worm

bins along with the salvaged

stock tank.

A little bit of hindsight is

showing me that a slight increase in surface area might allow us to add

on 2 more buckets up front while snugging them all better for a more

secure ride.

Funny how so much horse

manure can make you feel extra wealthy.

Bradley knows that Mark

and I are interested in trying out more kinds of wild game, so he

kindly brought a squirrel to work with him Wednesday morning. He

had shot it the night before, so the body had gone stiff overnight in

the fridge and took five minutes to skin --- a long time compared to

the one minute Bradley estimates it usually takes him.

After Bradley

illustrated the proper skinning and cleaning technique, we chopped the

carcass up into thirds as suggested and boiled the meat to provide our

lunch. Unfortunately, neither Mark nor I were thrilled by the

taste. I could have spiced it up relatively easily, but wanted to

get an idea of what squirrel really tasted like, so left it plain.

I'm not sure our analysis of

the flavor was really fair, though. When I was able to pretend I

wasn't eating squirrel, I thought it tasted a bit like chicken, but for

some reason the idea of eating a squirrel didn't sit well with

me. I don't think Mark was able to divorce the idea of "squirrel"

from what was on his plate at all.

I'm not sure our analysis of

the flavor was really fair, though. When I was able to pretend I

wasn't eating squirrel, I thought it tasted a bit like chicken, but for

some reason the idea of eating a squirrel didn't sit well with

me. I don't think Mark was able to divorce the idea of "squirrel"

from what was on his plate at all.

In a pinch, I'm now

confident that I could skin and gut a squirrel, and I suspect that

hidden in a pot of vegetable soup, neither of us would have any

complaints about squirrel meat. But for now, we're going to stick

to cultivated meat and venison, with the idea of rabbit still floating

around for later.

(As a side note, Lucy

was far more interested in the squirrel hide, head, and entrails than

she usually is in offal. Sounds like she, at least, has no

problem wrapping her head around eating squirrel.)

Before we dive into

composting humanure, it's worth understanding what happens to your crap

if you are plugged into a conventional system. Your waste is

commonly known as sewage, but in the industry, it's generally referred

to as wastewater (or possibly blackwater if you're making a distinction

between the output of your toilet and sink). Wastewater disposal

methods range from the simple to the complex, and Jenkins does a good

job of pointing out the pros and cons of each system.

Before we dive into

composting humanure, it's worth understanding what happens to your crap

if you are plugged into a conventional system. Your waste is

commonly known as sewage, but in the industry, it's generally referred

to as wastewater (or possibly blackwater if you're making a distinction

between the output of your toilet and sink). Wastewater disposal

methods range from the simple to the complex, and Jenkins does a good

job of pointing out the pros and cons of each system.

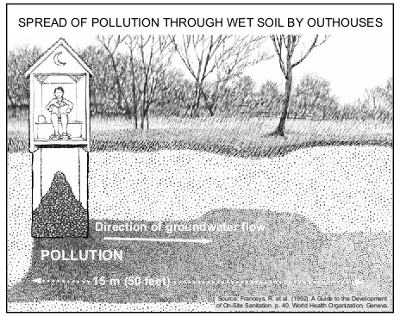

The cheapest way to

dispose of human waste is the pit latrine, which is basically our

system at the moment. The worst problem with a pit latrine is its

tendency to leak pollutants into the groundwater, which is why an

outhouse should always be more than fifty feet away from any well or

stream. Assuming you work around that issue, other problems

include disease-transmission, annoying flies, and smell, all of which

can be avoided by keeping the humanure covered with a high carbon

material after each use.

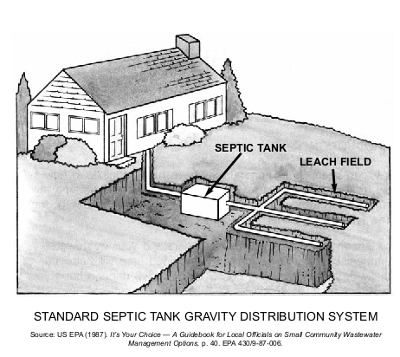

If your outhouse isn't

grandfathered in like ours, you'll be forced to install a septic system

in most parts of the United States. Septic system owners use a

conventional toilet inside the house, then the wastewater flows to a

septic tank for solids to settle out. The liquid continues on to

a leach field, which is simply a series of buried pipes that let water

drain out into the subsoil.

The biggest disadvantage

of septic systems, in my opinion, is cost, since even the cheapest

onces will set you back at least $2,000. In addition, you have to

pump the solids out of the

septic tank at intervals, and that material ends up being sent to a

wastewater treatment plant, which has its own problems. Finally,

Jenkins notes that concentrations of more than 40 septic systems per

square mile lead to subsurface contamination, which means that if you

and your neighbors have lots smaller than about 16 acres, septic

systems are a bad choice. (I suspect this same issue would come

into play with pit latrines/outhouses.)

pump the solids out of the

septic tank at intervals, and that material ends up being sent to a

wastewater treatment plant, which has its own problems. Finally,

Jenkins notes that concentrations of more than 40 septic systems per

square mile lead to subsurface contamination, which means that if you

and your neighbors have lots smaller than about 16 acres, septic

systems are a bad choice. (I suspect this same issue would come

into play with pit latrines/outhouses.)

In the city, wastewater

is pumped to a central treatment facility, which can use any of several

methods to treat the human waste. I won't go into wastewater

treatment plants much here since I doubt any of you are thinking of

installing one in your backyard, but Jenkins explains in great depth

why the facilities are problematic. In addition to the puzzle of

disposing of organic matter laced with toxins (due to treatment) and

the chlorinated effluent harming receiving streams, we waste energy by

treating water and then using it to flush our toilets.

The Humanure Handbook

asks us to step back and change our view of humanure. If we

consider our effluent to be a valuable form of organic matter rather

than something to dispose of, we can create systems that recycle

humanure into apples. Yes, humanure composting systems require a

little more time, but they also use less money and create less

pollution, so they fit the homesteading ethic to a T.

| This post is part of our The Humanure Handbook lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It took us a little over 2

hours to shuttle the new roofing tin from our parking area back to the

trailer.

The color we chose is called

Lightstone, and the manufacturer claims it should last at least 40

years at a cost of $1.87 per foot.

Be sure to check back with us

in 40 years for a detailed report on the exact condition of the metal

and how well it holds up over the next 4 decades.

This week is our last

chance to plant oilseed radishes, so I made a lot of hard-nosed

decisions. For example, I ripped out all of the older beds of

beans and just kept one to enjoy until the frost --- I'd rather miss

out on some subpar beans than lose a whole season of

cover-cropping. Similarly, the oilseed calendar is the main

reason I harvested

my sweet potatoes

this week, since I wanted to be able to put cover crops in the tubers'

place.

Meanwhile, I slipped

oilseed radishes into gaps where fall crops didn't come up, and I even

pulled back the mulch and tossed down seeds around sweet corn that will

be done bearing this week and around tomatoes that look too blighted to

last much longer. Since my new method of cleaning up after large

crops involves cutting the spent plants at ground level and leaving the

roots in place, removing the finished vegetables won't disrupt the

radish seedlings. And I figure the oilseed radishes won't get big

enough to compete before the corn and tomatoes are done.

Since Mark talked me

into splurging on 25 pounds of oilseed radish seeds, I'm trying out

some crazy experiments too. I

seeded an entire chicken pasture in oilseed radishes and planted some radishes

around the base of a young apple tree. I'm not too thrilled with

the pasture planting --- I think the shade set the cover crop back --

but the apple has sparse enough leaves that I think it might coexist

quite well with the radishes.

Unlike buckwheat seeds

(which get eaten up by cardinals in short order

if I don't sprinkle a light coating of straw over top after planting),

radish

seeds don't seem to be enjoyed by wildlife. So I simply scatter the

radish seeds on the soil surface by eye, often ending up seeding

thicker than I really should (like in the photo above). I figure

it's worth a bit more seed to keep effort to a minimum.

All told, I used 12

pounds of oilseed radish seeds this year, which cost about $43.

If I figure I planted about 5 pounds of that in 27 beds in the garden

(with the rest going into the pasture), that comes to 66 cents per bed,

compared to maybe 83 cents per bed if I overwintered the garden by

mulching it with straw. Of course, it

would be considerably cheaper to use oats as our winter cover crop, but we wanted to give

oilseed radishes a more serious try this year to see if they're worth

the extra money.

In case you haven't been

following along for the last couple of years, here are some relevant

posts about oilseed radishes:

- The

potential of oilseed radishes

- My two favorite no-till winter cover crops

- When to plant oilseed radishes

- How

to kill no-till cover crops

- What oilseed radishes look like in February

- Organic matter production of my favorite cover crops

- Improving soil with cover crops

- Choosing

cover crops

Hopefully that'll

inspire you to try out some cover crops in your garden, if not this

year, then next.

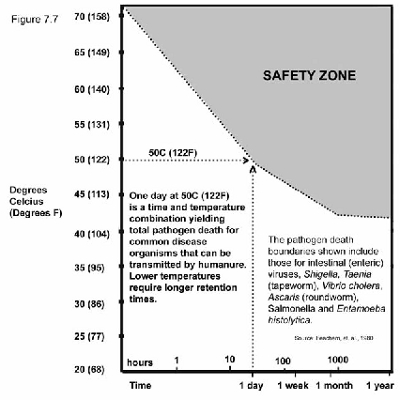

Next week, I'll continue our

humanure lunchtime series by delving into several different types of

composting systems. However, before you get too excited, I want

to take a step back and consider the biggest issue with humanure

composting.

Next week, I'll continue our

humanure lunchtime series by delving into several different types of

composting systems. However, before you get too excited, I want

to take a step back and consider the biggest issue with humanure

composting.

No, I'm not talking

about disease. Joseph Jenkins does an admirable job of explaining

how a well-managed humanure recycling system is perfectly safe.

(Check out The

Humanure Handbook if

you don't believe me.) I'm more concerned with an issue that's

already problematic on our farm --- a paucity of high

carbon materials.

We've been experimenting with deep

bedding in our

chicken coop for the last couple of years, which is a bit like a

humanure composting system for chickens. Theoretically, the idea

has merit, and it does work pretty well in practice, but I'm always

scrambling in search of quality bedding.

We've been experimenting with deep

bedding in our

chicken coop for the last couple of years, which is a bit like a

humanure composting system for chickens. Theoretically, the idea

has merit, and it does work pretty well in practice, but I'm always

scrambling in search of quality bedding.

In a pinch, I can use straw, but I don't like buying carbon for my

chickens to poop on, and the optimal bedding is higher in carbon and

smaller in size so chickens can scratch through and mix the bedding

regularly. When we run out of autumn leaves, either raked from

the woods or collected by my kind mother during city trash pickup days,

manure piles up, smells turn foul, and flies start to plague our porch

dinners. The conclusion is: we don't have enough high carbon

materials for essential uses right now without diverting some to a

humanure composting system.

Jenkins recommends

hunting down 20 cubic feet of sawmill sawdust per hundred pounds of

human body weight in the household per year, which (rounding up to

include guests and to give us a bit of wiggle room) would equate to 80

cubic feet (600 gallons) for us. That's 120 five gallon buckets

or 7 of our 95

gallon wheelie bins full --- a pretty hefty helping of sawdust for

which

we've yet to find a source. In addition, he recommends having

about ten bales of straw or hay on hand for covering the outdoor

pile. (I'll explain more about the uses of the two types of high

carbon material in a later post.)

Jenkins does offer sawdust

alternatives, including peat moss, leaf mould, rice hulls, or grass

clippings (although I'm not so sure grass clippings would work well ---

they're pretty high in nitrogen). However, all of those sources

would either have to be bought or would require considerable effort to

gather, making their use equally problematic.

Jenkins does offer sawdust

alternatives, including peat moss, leaf mould, rice hulls, or grass

clippings (although I'm not so sure grass clippings would work well ---

they're pretty high in nitrogen). However, all of those sources

would either have to be bought or would require considerable effort to

gather, making their use equally problematic.

Mark isn't a fan of humanure composting, so he was very relieved when I

told him I couldn't even consider a system until we stock up on enough

high carbon bedding for the chickens plus a year's supply for a

humanure system. Looks like we'll be scouring the countryside in

search of a sawmill....

| This post is part of our The Humanure Handbook lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We've got a new batch of

fresh chicks. The last one of 2012.

They seem to have made

themselves at home and look at the new observation window with

curiosity.

Maybe being curious at such a

young age will make them better at foraging for bugs?

Celery is one of the

herbs/vegetables I used to eat a lot, but found too nitpicky to grow in

my garden. Luckily, I discovered that parsley fills in very well

as a substitute in soups and salads during the spring, fall, and

winter, although in the middle of summer, the herb becomes too woody

and strong to be pleasant raw.

This year, I decided to

try a new celery substitute for those hot summer months --- Par-cel

cutting celery, an heirloom herb dating back to eighteenth century

Netherlands. Cutting celery looks a lot like parsley, with small

stems and lots of leaves, but tastes more like celery. I found

the ribs and leaves very pleasant in tuna salad this year, but would

warn you that if you don't like the slightly bitter taste of celery

leaves, you won't like cutting celery --- there are a lot more leaves

than stalks.

The other downside of

cutting celery is that it didn't seem to want to germinate when

direct-seeded at the frost-free date in my garden. Out of my

small trial packet of 200 seeds, I only ended up with two plants.

If you want to try it out, I suspect that cutting celery might be

better started in flats so you can keep the moisture levels just right

for speedy germination.

We replaced the

old 12

amp Skil saw with the

next step up this week.

The main lesson I learned is

to keep an eye on the sharpness of the blade and to put a fresh one on

before it's too late.

It came with a nice tote bag

that could double as a purse for the ladies out there with an

industrial twist to their fashion sense. Perfect for date night when

you want to sneak a six pack of beer into the theatre.

Ten

Acres Enough was

originally published in 1864, but the farming memoir stands the test of

time extremely well. I picked up the Norton Creek Press edition,

which includes Robert Plamondon's occasional footnotes and careful

calculations of what the original dollar amounts would come to in

today's terms. If you don't mind foregoing those small

conveniences, though, you can

read the book online for free.

Ten

Acres Enough was

originally published in 1864, but the farming memoir stands the test of

time extremely well. I picked up the Norton Creek Press edition,

which includes Robert Plamondon's occasional footnotes and careful

calculations of what the original dollar amounts would come to in

today's terms. If you don't mind foregoing those small

conveniences, though, you can

read the book online for free.

Those of you who were

struck by the careful use of organic matter in Farmers

of Forty Centuries

will be intrigued by Edmund Morris's fascination with manure. His

first year on the farm, he spent $248 on manure ($5,700 in today's

dollars), and when he had more money on hand, he was happy to part with

$358 ($8,228 today) for manure during his third year. He chose to

keep his livestock completely confined and cut

clover from his field to feed them as a way of maximizing his homegrown

manure production, and he also collected tree leaves from the wild to

add to the compost pile. All told, perhaps a third of Ten

Acres Enough is

devoted to discussions of organic matter.

The larger theme, though, is

how to make a simple but dependable living on a ten acre farm. I

doubt that an American farmer could follow Morris's lead today due to

competition with factory farms, but some of his points are just as

valid now as they were a century and a half ago. Morris believed

strongly that debt is the downfall of many a businessman (since he

struggled against the problem for the first many years of his

life). He was also keen on focusing on a quality product (unique

if possible) marketed to a wealthy urban clientele.

The larger theme, though, is

how to make a simple but dependable living on a ten acre farm. I

doubt that an American farmer could follow Morris's lead today due to

competition with factory farms, but some of his points are just as

valid now as they were a century and a half ago. Morris believed

strongly that debt is the downfall of many a businessman (since he

struggled against the problem for the first many years of his

life). He was also keen on focusing on a quality product (unique

if possible) marketed to a wealthy urban clientele.

In the introduction,

Robert Plamondon describes this classic text as follows: "Ten

years after Henry

David Thoreau

learned how to be a poor farmer, Edmund Morris learned how to be a good

one." I totally agree. If you're interested in a glimpse

into American small farm life in the 1850s, this quick and fun read is

the book for you.

The main symptom of a dull

circular saw blade is the motor bogging down making cuts harder to push

through.

Above is a side by side

comparison of our old 12

amp Skil saw blade and a

brand new carbide tipped blade.

Maybe a circular saw from the

future will have a feature where it scans each tooth and shuts down or

beeps when the dullness is too much for the motor to handle.

One of our goals in

creating the Walden Effect Annex is to build our community, either by

bringing in likeminded folks from outside the area or by tempting

intriguing locals to come out of the woodwork. While the Annex

remains a work in progress, Mark and I made a start on the second goal

this weekend by creating a Meetup group --- the Extreme

SW Virginia Permaculture Guild.

Do you want to learn more about forest gardening, homegrown edible mushrooms, top bar hives, or vegetable varieties that do well without chemicals? Do you want to talk to someone who's heard of Paul Stamets, Joel Salatin, or Bill Mollison (and maybe bring one of these experts to speak in our region)? Perhaps you'd like to meet up with folks interested in creating a cowshare or intentional community? If so, this group is for you, no matter how little or much experience you've had with permaculture in the past.

We're currently planning a seed swap full of heirloom tomatoes, locally adapted garlic, old-timey beans, and much more, with date and location to be announced on the meetup group soon. Everyone who lives within driving distance of Dungannon, Virginia, is welcome to join --- just follow the link and click the "Join us!" button in the upper right hand corner of your screen. I'm looking forward to meeting you soon.

Our POOP-free chicken waterer is sponsoring the first year

of Meetup fees, so membership is free.

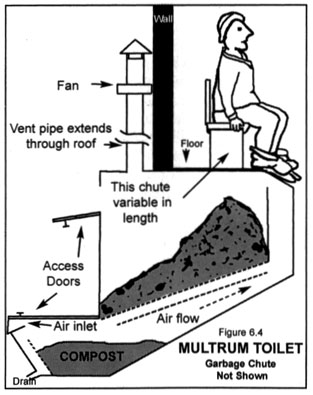

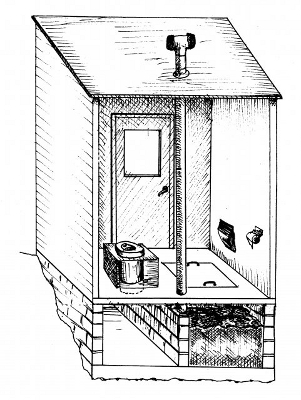

Before The

Humanure Handbook

hit the stage, most of the systems in practice were cool composting

toilets. In contrast to Jenkins' thermophilic composting system

(which I'll discuss in Thursday's post), these cool composting systems

relied on time to kill off any pathogens in the humanure.

Before The

Humanure Handbook

hit the stage, most of the systems in practice were cool composting

toilets. In contrast to Jenkins' thermophilic composting system

(which I'll discuss in Thursday's post), these cool composting systems

relied on time to kill off any pathogens in the humanure.

In general, leaving a

pile of humanure to compost for two years is a sufficient safety margin

even if the pile doesn't heat up at all, although roundworm eggs can

survive for up to ten years under these conditions. If you apply

composted humanure under the mulch around ornamentals or fruit trees,

though, this issue may not matter.

The Clivus Multrum is

probably the best known of the cool composting systems, and most of the

other designs work similarly. Jenkins recommends designing a cool

composting toilet with at least two chambers so you can close off one

after filling and let the humanure age for a couple of years before

removing the compost. When starting a new chamber, fill it about  halfway with an

absorbent, high carbon material, then keep more of the

sawdust on hand to drop down the hole after each use. A

chimney-pipe-type ventilation system will pull any smells up above

nose-level, and leachate can be collected in a five gallon bucket of

sawdust that is tossed back down the hole at intervals.

halfway with an

absorbent, high carbon material, then keep more of the

sawdust on hand to drop down the hole after each use. A

chimney-pipe-type ventilation system will pull any smells up above

nose-level, and leachate can be collected in a five gallon bucket of

sawdust that is tossed back down the hole at intervals.

Despite the problem with

using humanure compost from this type of toilet on food crops, it does

have a major advantage --- simplicity. Unlike Jenkins' system,

there's little regular maintenance required beyond finding sawdust, and

the compost is high quality after the extended aging period.

I'd be curious to hear

from anyone who's using a cool composting system like this. What

design did you use (or what brand did you buy)? How has it worked

out for you? Do you have additional pros and cons to add to this

description?

| This post is part of our The Humanure Handbook lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The framing should be

finished up tomorrow on the mobile

home roof project.

Insulation and metal after

that will make the winter warm and drip free.

When I delved into the Warre hive for the first time last

week, I learned why I sometimes see Warre beekeepers with a wire tool a

bit like a cheese-slicer. The boxes aren't as keen on coming

apart as Lanstroths are, so I accidentally ripped part of a few combs

in half when they stuck to the top bars of the hive body below. I

guess I'll have to rig some kind of wax-slicer for the next time I open

the hive...a year from now.

When I delved into the Warre hive for the first time last

week, I learned why I sometimes see Warre beekeepers with a wire tool a

bit like a cheese-slicer. The boxes aren't as keen on coming

apart as Lanstroths are, so I accidentally ripped part of a few combs

in half when they stuck to the top bars of the hive body below. I

guess I'll have to rig some kind of wax-slicer for the next time I open

the hive...a year from now.

In the meantime, we'll

be pouring

sugar water down the bees' gullets to make sure they double

their winter

stores in the next

month. Except for only having only one box full of  honey,

the hive looked quite healthy, with a lot of new workers about to hatch

out and get to work collecting ragweed pollen and goldenrod nectar.

honey,

the hive looked quite healthy, with a lot of new workers about to hatch

out and get to work collecting ragweed pollen and goldenrod nectar.

I also noticed that my ant

problem had been

taken care of with a biological control --- a skink moved into the

quilt. I love how the neglect method solves so many farm pest

problems.

We bought all of

Bradley's father's honey this summer since we want our bees to keep

everything they produce during their first year. I'm debating

splitting the hive next year and spending another year without

homegrown honey, or trying to find a local nuc next spring to increase

our apiary while allowing this first hive to feed us. Even though

the decision seems far in the future, we learned the hard way that

tracking down local bees should be started early, so we'll probably

choose between our options soon.

When keeping any animal, one of

the necessities is, of course, providing food and water. This post will

cover how I am providing water for my rabbits.

When keeping any animal, one of

the necessities is, of course, providing food and water. This post will

cover how I am providing water for my rabbits.

The result of my efforts is a

bit of an experiment involving some creativity in providing a constant

source of water for my rabbits, while not requiring that I tend to

their water needs manually every day. We have more problems here with

heat of the summer than freezing in the winter, so freezing isn't much

of a concern. Heat issues are very much a concern though, so water is

important.

We started with the

traditional rabbit water bottles until we could build the system that we

wanted. We also used one rabbit as a test subject to see if we could get

him to drink from one of Mark and Anna's chicken water

nipples. He took to this

method of drinking pretty well, so we then decided to expand on the

test. All three of the rabbits we have at present will now be drinking

from this watering system. And...it's expandable.

I started out with a handful

of supplies and some tools seen below:

I used a toilet

tank fill valve assembly to autofill a bucket with water. I used part of an old broken

fill valve assembly to make the outlet in the bottom of the bucket.

From there, I used PVC pipe to go into the rabbit hutch.

I used a toilet

tank fill valve assembly to autofill a bucket with water. I used part of an old broken

fill valve assembly to make the outlet in the bottom of the bucket.

From there, I used PVC pipe to go into the rabbit hutch.

The chicken waterers seem to

be 1/8 male tapered pipe threads, so I used a drill bit and tap to

thread some PVC end caps. The waterer nipples are then screwed into

these, and it seems to work pretty well. I drilled and tapped the end

caps at a bit of an angle to make it easier for the rabbits to drink

from them. I'd say it's about a 20

degree angle...and they seem to still seal OK.

The bucket is suspended above the

hutch to give head pressure, and a benefit during dry times is

that we have a drip line that comes off the bucket to water some nearby

plants. This also keeps the

water in the bucket a bit fresher for the rabbits. There's a Y adapter

and shut off so we can drain the bucket and/or shut off the drip line.

The bucket is suspended above the

hutch to give head pressure, and a benefit during dry times is

that we have a drip line that comes off the bucket to water some nearby

plants. This also keeps the

water in the bucket a bit fresher for the rabbits. There's a Y adapter

and shut off so we can drain the bucket and/or shut off the drip line.

So far, the rabbits seem to

take to it pretty well. And it makes keeping them well watered almost

no effort at all.

Dawn managed to catch this footage of one of our rabbits drinking a few days after the new system was installed.

Shannon and Dawn will be sharing their experiences with raising meat rabbits on Tuesday afternoons. They homestead on three acres in Louisiana when time off from life and working as a sys admin permits.

It was a great day for

sliding metal up a ladder.

A bit more sliding and we'll

have a complete roof sometime tomorrow.

I was shocked to wake up

Tuesday morning to chilly weather in the mid 40s. While I'm never

really ready to see summer go, we've reached our freezer goals (20

gallons, mostly soup) and have changed over to drying

tomatoes for winter

treats.

The fall garden is starting

to produce, and I've been zipping back through with another round of

weeding and mulching before the ground becomes too cold to enjoy

sinking my hands into. Winter weeds have snuck into small spots

of bare ground where I pulled the mulch back to plant seedlings, and I

want to stay ahead of them.

The fall garden is starting

to produce, and I've been zipping back through with another round of

weeding and mulching before the ground becomes too cold to enjoy

sinking my hands into. Winter weeds have snuck into small spots

of bare ground where I pulled the mulch back to plant seedlings, and I

want to stay ahead of them.

Now's also a good time

to kill mulch "lawn" areas that I want to fill with perennials this

winter or vegetables next spring. Mark's done a great job of

reclaiming some brambly patches with persistant mowing this summer, so

a simple kill mulch will be enough to turn those areas into arable

ground.

Despite planning ahead

for fall, winter, and even next spring, I'm far from ready for a

frost. Our average first frost date is October 10, but Bradley

predicts freezing weather to come before the end of September.

What do you think?

In the third selection

from Radical

Homemakers, Shannon

Hayes left the realm of theory and began to explore the similarities

she'd noticed among the radical homemakers interviewed. She

explained that radical homemakers had redefined poverty and wealth,

finding joy in free time, a strong marriage (if applicable), happy

friendships, a cohesive family, and good food rather than striving to

achieve the highest earning potential.

The chapter sought to

dispel the myth that the following facets of middle class life are

unachievable in a single- (or no-) wage-earner household:

- Transportation

- Housing

- Health care

- Child care

- Education

- Retirement

Many of the radical

homemakers' methods of achieving these goals on the cheap were

inspiring --- focusing on good food, low stress, and community bonds to

ensure your health, for example. Other methods were obvious ---

there's no need to pay for child care if at least one parent is at home

full time.

But I was struck by how

middle class all of the assumptions (and participants) were. Many

of the radical homemakers chose to homeschool and not jump through the

expensive and time-consuming hoops required to get their kids into the

right preschool so they could get into the right private school and

then into the right college. And yet, 27% of those parents had

gone to grad or med school and 30% had a bachelor's degree (usually

listed as being from a prestigious private school), while only 3% and

6% had chosen the traditionally lower class options of the military or

a community college/technical school. (Actually, I suspect those

higher education percentages are underestimates --- anyone whose bio

didn't explicitly mention their education went into my "potentially

high school" category, but many of those people may simply have not

self-identified based on their school.) Those statistics tell me

that the majority of the participants in the study were culturally

middle class people who had access to options not available to the

average American.

But I was struck by how

middle class all of the assumptions (and participants) were. Many

of the radical homemakers chose to homeschool and not jump through the

expensive and time-consuming hoops required to get their kids into the

right preschool so they could get into the right private school and

then into the right college. And yet, 27% of those parents had

gone to grad or med school and 30% had a bachelor's degree (usually

listed as being from a prestigious private school), while only 3% and

6% had chosen the traditionally lower class options of the military or

a community college/technical school. (Actually, I suspect those

higher education percentages are underestimates --- anyone whose bio

didn't explicitly mention their education went into my "potentially

high school" category, but many of those people may simply have not

self-identified based on their school.) Those statistics tell me

that the majority of the participants in the study were culturally

middle class people who had access to options not available to the

average American.

I could pick apart other

middle class assumptions (especially in the housing and income levels

of the radical homemakers), but I wanted to throw this week's thought

question out to my readers before you all roll your eyes and move

on. A couple of you commented on last

week's post to say

that when you're truly poor, you can't help working long hours to

support your family. With that in mind, I'm beginning to wonder

whether Radical

Homemakers really

represents a template that we can all use to live well on less, or

whether the book should be subtitled "how not to go quite as crazy as a

middle class American." We've

discussed this topic in relation to Walden previously, but

I thought it was worth rehashing with a more modern perspective.

What do you think?

I could pick apart other

middle class assumptions (especially in the housing and income levels

of the radical homemakers), but I wanted to throw this week's thought

question out to my readers before you all roll your eyes and move

on. A couple of you commented on last

week's post to say

that when you're truly poor, you can't help working long hours to

support your family. With that in mind, I'm beginning to wonder

whether Radical

Homemakers really

represents a template that we can all use to live well on less, or

whether the book should be subtitled "how not to go quite as crazy as a

middle class American." We've

discussed this topic in relation to Walden previously, but

I thought it was worth rehashing with a more modern perspective.

What do you think?

If you're still reading

along, we'll finish up the book by discussing chapters six and seven

(and the profiles if you feel so inclined) next Wednesday. Then

we'll take a week off before diving into a book that I've been itching

to savor for months --- The

Holistic Orchard by

Michael Phillips. I'm not sure how this text will do as a book

club selection since it's more factual and less philosophical than the  other ones we've been

discussing, but I have a feeling from the sections I've dipped into

that Phillips' new book will change the way we all look at fruit trees

and bushes, and I know it's one of the few books that will make the cut

and stay on my permanent bookshelf. So put in that interlibrary

loan request now and we'll start discussing chapter 1 of The

Holistic Orchard

on October 3.

other ones we've been

discussing, but I have a feeling from the sections I've dipped into

that Phillips' new book will change the way we all look at fruit trees

and bushes, and I know it's one of the few books that will make the cut

and stay on my permanent bookshelf. So put in that interlibrary

loan request now and we'll start discussing chapter 1 of The

Holistic Orchard

on October 3.

If

you want to be the first one on your block to see Walden Effect

readers' homesteading innovations in print, preorder your copy of The

Weekend Homesteader today.