archives for 08/2012

Crawdads (known to most of

the world as crayfish) show up in the garden if the spot is already

troubled. Only our back garden, with its high groundwater and low

topsoil, shows signs of crawdads, but there the crustaceans can cause a

bit of trouble. They aren't actively eating my plants, but they

do send up new chimneys to excavate their underground burrows from time

to time, and the piles of mud tend to squash seedlings.

Crawdads (known to most of

the world as crayfish) show up in the garden if the spot is already

troubled. Only our back garden, with its high groundwater and low

topsoil, shows signs of crawdads, but there the crustaceans can cause a

bit of trouble. They aren't actively eating my plants, but they

do send up new chimneys to excavate their underground burrows from time

to time, and the piles of mud tend to squash seedlings.

I'm far from an expert at crayfish, but I once had a scientist identify

our brilliantly blue crayfish as Upland Burrowing Crayfish (Cambarus dubius). This

species is one of the few that spends nearly all of its time

underground (rather than living in a creek or pond), although the

crawdads do come out at night to eat decaying organic matter and

insects.

The point of the burrow isn't

just protection from predators --- the caverns dip down into the

groundwater so that these crawdads can keep their gills wet enough to

breath even during droughts. This particular species builds

pretty big burrows, sometimes extending three feet into the earth and

with up to five entrances, and several crawdads can live in each

one. No wonder they kick up so much mud into my garden.

The point of the burrow isn't

just protection from predators --- the caverns dip down into the

groundwater so that these crawdads can keep their gills wet enough to

breath even during droughts. This particular species builds

pretty big burrows, sometimes extending three feet into the earth and

with up to five entrances, and several crawdads can live in each

one. No wonder they kick up so much mud into my garden.

I've been trying to find the positive side of crawdads in the garden

ever since I moved into their habitat. My first thought was that

the crustaceans should be good for chickens to eat, but our hens ran

away from the crawdads we caught for them. (Bradley suggested

that his cats won't eat the burrowing crawdads but do like the ones in

the creek, so I might try again with creek dwellers later.)

I've now decided to think of burrowing crawdads as dynamic

accumulators who are helping build the problematic back garden

soil. After all, they aerate the ground with their burrows and

haul organic matter down to improve the earth at lower levels.

I'll keep telling myself that every time the burrows slaughter a

vegetable seedling and maybe I won't get so angry.

"A farm is a manipulative

creature. There is no such thing as

finished. Work comes in a stream and has no end. There are

only the

things that must be done now and the things that can be done

later.

The threat the farm has got on you, the one that keeps you running from

can until can't is this: do it now, or some living thing will wilt or

suffer or die. It's blackmail really."

"A farm is a manipulative

creature. There is no such thing as

finished. Work comes in a stream and has no end. There are

only the

things that must be done now and the things that can be done

later.

The threat the farm has got on you, the one that keeps you running from

can until can't is this: do it now, or some living thing will wilt or

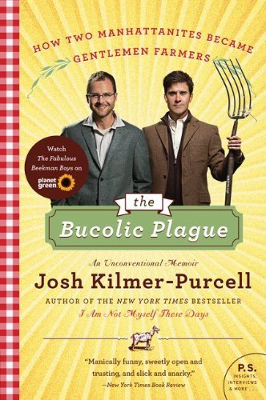

suffer or die. It's blackmail really."In The Dirty Life, Kristin explains how she and her husband-to-be spent their first year "building a wildly complex farm all at once." Mark (hers, not mine) had the vision of creating a CSA that provided a full diet, from meat and dairy to grains and vegetables...and he wanted it up and running by August. Since the duo only moved onto the farm that winter and planned to work the ground using draft horses, they faced extremely long, back-breaking days to make their dream a reality.

One of the hardest lessons I've learned on

our homestead is the issue of pacing. You can see throughout The

Dirty Life how

biting off nearly more than they could chew stressed Kristin and Mark

almost to the breaking point, and the quote at the top of this post

explains why it's so hard to scale back your vision once you've started.

One of the hardest lessons I've learned on

our homestead is the issue of pacing. You can see throughout The

Dirty Life how

biting off nearly more than they could chew stressed Kristin and Mark

almost to the breaking point, and the quote at the top of this post

explains why it's so hard to scale back your vision once you've started.Eventually, Mark and Kristin settled on a "no-farming-on-Sundays rule", but they could have saved a lot of heartbreak if they'd been less ambitious from the get-go. Kristin wrote about an early winter blizzard-turned-planning-day:

"We spent the day in a fit of joyful

enthusiasm, mapping out the next year of work.... We filled in

the days and weeks with our ambitions, which even then we must have

known were too big to be contained in the boundaries of a single

year. The first week in February was reserved to FIGURE OUT

GREENHOUSE---BUILD IT! In the second week of that month, we would

aim to BUILD DISTRUBUTION AREA and also, somehow, cut and split the

next year's FIREWOOD. The day in October when we planned to get

married Mark had written WEDDING, and below that, on the same day's

square, 50 CHICKS ARRIVE.... The following week he had written

HONEYMOON and also, neatly, EXTRACT HONEY FROM THE HIVE."

Of course, the obvious take-home message is "don't marry a Swarthmore graduate" --- I suspect Kristin's Mark and I have more in common than our overambitious plans, and we do make tough spouses. But if teaming up with a Swattie wasn't in the cards anyway (or if it's too late to back out now), I think even folks homesteading on a small urban lot should think twice about how much time they really have when planning the year's garden and selecting starter livestock. My new rule of thumb is to figure everything will really take at least twice as long as I think it will, which pads our schedule against inevitable emergencies and lowers my stress levels considerably.

For those of you who have been homesteading a while, did you bite off more than you could chew during year one? And, for everyone, what strategies have you used to lower your ambitions down to realistic levels?

Those of you new the book club might want to check out last week's post about part one of The Dirty Life. We'll be discussing part three next Wednesday, and my copy of the book is now up for grabs --- whoever emails me first gets it. (Congratulations, Irma! You're the winner.)

Meanwhile, I wanted to give you a heads-up so you could hunt down the next book club read in a timely manner. "Radical Homemakers is about men and women across the U.S. who focus on home and hearth as a political and ecological act, and who have centered

their lives around family and

community for personal fulfillment and cultural change. It explores

what domesticity looks like in an era that has benefited from feminism,

where domination and oppression are cast aside and where the choice to

stay home is no longer equated with mind-numbing drudgery, economic

insecurity, or relentless servitude." We'll start discussing on

August 29, which should give you plenty of time to hunt down the book

on interlibrary loan.

their lives around family and

community for personal fulfillment and cultural change. It explores

what domesticity looks like in an era that has benefited from feminism,

where domination and oppression are cast aside and where the choice to

stay home is no longer equated with mind-numbing drudgery, economic

insecurity, or relentless servitude." We'll start discussing on

August 29, which should give you plenty of time to hunt down the book

on interlibrary loan.My paperback includes three chapters not found in the original ebooks, all of which focus on less hands-on lessons like pacing.

I tried giving the Sensor

Plug a sharp blow to the the side of the case by slamming it into a

table top like Zimmy suggested in a comment last week.

That brute force cure worked

at bringing life back to this product. Now the Sensor Plug will eventually turn

whatever is plugged in off, and then turn it back on when movement is

detected. I'm just not sure yet what the interval length is.

Not sure if that proves it

must have a mechanical relay or maybe the adjustment potentiometer was

damaged and the jolt brought it back to a proper state of providing

variable resistance.

Preserving

Food Without Freezing or Canning is a fascinating and

thought-provoking book that has an entirely different feel from most

modern homesteading books. The project started when a French

gardening magazine asked its readers to share old-fashioned fruit and

vegetable preservation recipes, so the resulting compilation feels a

bit like an oral history turned into a cookbook.

Preserving

Food Without Freezing or Canning is a fascinating and

thought-provoking book that has an entirely different feel from most

modern homesteading books. The project started when a French

gardening magazine asked its readers to share old-fashioned fruit and

vegetable preservation recipes, so the resulting compilation feels a

bit like an oral history turned into a cookbook.

When you find a copy, I

recommend that you start by flipping to the appendix, which in many

ways is the most valuable part of the book. I've spent years

slowly figuring out which preservation technique works best for each

fruit and vegetable, and the authors of this book have created a quick

tabular view of that information. For example, they show that

onions are best stored whole on the shelf, but that you can also

preserve them by drying, lactic fermenting, or adding vinegar.

In general, the authors

recommend drying fruits and lactic fermenting most vegetables --- I

definitely agree with the former and might have to get over my

anti-pickle sentiment enough to try the latter. In fact, after

reading through the entire lactic fermentation section, I settled on

Swiss chard ribs as a good starter recipe since the authors of the

recipe note "Swiss chard ribs are not acidic. Our children dread

lacto-fermented green beans, but they love the milder taste of Swiss

chard." I'll let you know if Mark and I feel the same way once

our first lactic fermentation experiment is ready at the end of August.

In general, the authors

recommend drying fruits and lactic fermenting most vegetables --- I

definitely agree with the former and might have to get over my

anti-pickle sentiment enough to try the latter. In fact, after

reading through the entire lactic fermentation section, I settled on

Swiss chard ribs as a good starter recipe since the authors of the

recipe note "Swiss chard ribs are not acidic. Our children dread

lacto-fermented green beans, but they love the milder taste of Swiss

chard." I'll let you know if Mark and I feel the same way once

our first lactic fermentation experiment is ready at the end of August.

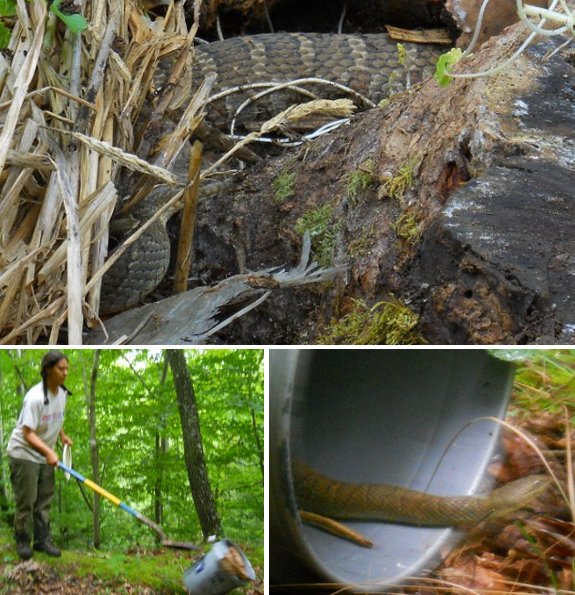

Today we had what we're

pretty sure was a copperhead

snake living underneath a piece of cardboard near Lucy's house which is

also near the garden.

We briefly debated the option

of killing it. Neither of us liked the idea of destroying something so

beautiful, so we decided to carefully coax him into a 5 gallon bucket

with a tempting piece of cardboard to hide under.

Once we had the lid on tight

we walked him to a place pretty far away across the creek and tipped

the bucket over.

As

soon as the calendar flipped over to July, I could feel the slow

descent into winter begin. I was already planting fall

crops, and the

scorching heat in June made our normal summer temperatures in July feel

relatively cool.

As

soon as the calendar flipped over to July, I could feel the slow

descent into winter begin. I was already planting fall

crops, and the

scorching heat in June made our normal summer temperatures in July feel

relatively cool.

August seems even more

like the beginning of fall. I spent all morning Thursday setting

out broccoli and Brussels sprouts seedlings (a little late for both,

but I hope they'll make it, perhaps with a little frost

protection). This week also marked the first round of oilseed

radishes, planted in

beds that will now be fallow until spring, along with the last seeding

of a summer crop (one more bed of crookneck squash.)

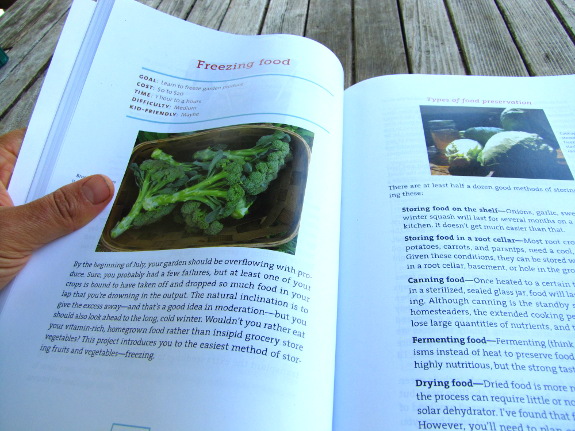

Despite seeing winter on the

horizon, our summer crops are coming in with a vengeance. I sent

Mark to town Tuesday with two big bags of squash and cucumbers --- "and

don't come home until they're all gone!" (He foisted the

vegetables off on appreciative librarians.) I'm saving seeds and

freezing winter soup as fast as I can too, of course.

Mark to town Tuesday with two big bags of squash and cucumbers --- "and

don't come home until they're all gone!" (He foisted the

vegetables off on appreciative librarians.) I'm saving seeds and

freezing winter soup as fast as I can too, of course.

Even the winter

keepers are starting to ripen. The earliest-planted butternut

squash are turning brown, and the leaves are beginning to lose their

vibrant summer form.

It's hard to believe

that we only have five frost-free months to grow all of these tender

vegetables, but somehow it all gets done (and they all get

eaten). Good thing we budget time to simply enjoy the bounty!

I've been using this new Discovery Expedition vented fedora hat for a few

months now.

The extra shade it provides

compared to a regular hat makes it worth every penny of its 30 dollar

price, but the real advantage in my opinion is the all around screen

material on top. Combine 360 degrees of venting with the small space

the fedora shape creates between the top of your head and the top of

the hat and you've got some serious cooling of your noggin.

I'm guessing the additional

surface area of the brim has over twice the sweat absorbing power as a

conventional baseball hat. It's made in Sri Lanka and comes with a neck

strap that I deleted.

This year, I decided to

try out two tomato varieties I'd never grown before. To my

surprise, I ended up with four new kinds of tomatoes in my garden,

three of which were duds.

- Gold Rush Currant --- For the past few years, Blondkopfchen has been our favorite tommy-toe. The variety is prolific and tasty, but tends to succumb to fungal diseases before anyone else, so I figured it wouldn't hurt to try out a different type of cherry tomato. Unfortunately, Gold Rush Currant succumbed even faster and didn't taste good --- we won't be growing it again.

Amish Paste --- Most of

our tomatoes are romas, which we turn into soups,

sauces,

or dry.

I'm actually very happy with Martino's Roma, but so many people were

glowing about Amish Paste that I had to give it a shot. Amish

Paste turns out to be very similar to the Russian Romas we tried in our

early years on the farm --- huge, juicier than most roma tomatoes, but

extremely blight-prone. I don't mind spending a bit more time

processing my romas if they don't keel over in our damp climate, so I

ripped out the Amish Paste tomatoes this week before they could spread

their fungi to the rest of the planting.

Amish Paste --- Most of

our tomatoes are romas, which we turn into soups,

sauces,

or dry.

I'm actually very happy with Martino's Roma, but so many people were

glowing about Amish Paste that I had to give it a shot. Amish

Paste turns out to be very similar to the Russian Romas we tried in our

early years on the farm --- huge, juicier than most roma tomatoes, but

extremely blight-prone. I don't mind spending a bit more time

processing my romas if they don't keel over in our damp climate, so I

ripped out the Amish Paste tomatoes this week before they could spread

their fungi to the rest of the planting.- Japanese Black Trifele

--- Usually, we just eat Stupice as

an early and prolific slicing tomato. But during our early years,

we grew a variety that was supposedly Cherokee, and it was the tastiest

tomato imaginable (although blight-prone). Since I was given the

variety by a friend, I wasn't terribly surprised when images on the

internet didn't match the tomato I was growing, and extensive searching

showed that my tasty tomato was probably Japanese Black Trifele

instead. I bought some seeds of this new/old variety, and the

fruits do indeed look like the tomatoes I grew in 2007. However,

they taste watery and lack the flavor burst of whatever we grew then,

so Japanese Black Trifele will join the other duds on this year's

tomato trial list. (Unlike the previous two varieties, though,

I'll keep this one in the 2012 garden and will just cook with the so-so

fruits.)

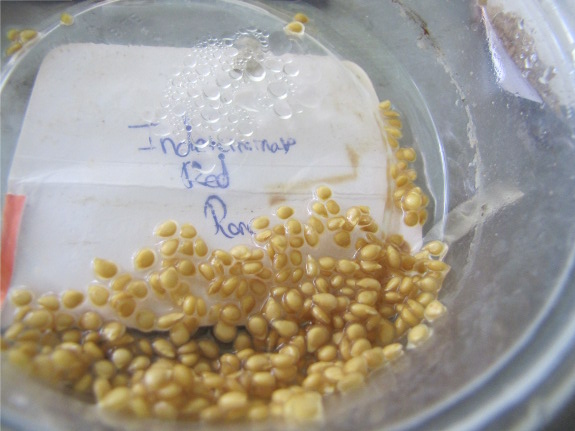

Unknown small, indeterminate roma

--- My final new variety for this year is who-knows-what! Since

volunteer tomatoes come up all over my garden from compost (some of

which is our ex-neighbors'), I can't be sure that this seedling wasn't

from a storebought tomato our friends ate last year. However, the

sport came up in the row with the Martino's Romas, which makes me think

that it might be either a seed of another variety accidentally slipped

into the packet, or a rare instance of a naturally produced hybrid

tomato. No matter where it came from, I like the unidentified

variety so far. It fruits just as prolifically as Martino's Roma

(although with smaller tomatoes), and is indeterminate, which means it

might end up giving us more tomatoes in the long run. The little

red roma does seem to be a bit more blight-prone (as you can tell by

how high up I've cut leaves on the stem), but once the rains slacked

off, the plant began to hold its own, unlike the first two varieties

profiled in this post. I'm saving

seeds and will try this variety out in more numbers next year.

Unknown small, indeterminate roma

--- My final new variety for this year is who-knows-what! Since

volunteer tomatoes come up all over my garden from compost (some of

which is our ex-neighbors'), I can't be sure that this seedling wasn't

from a storebought tomato our friends ate last year. However, the

sport came up in the row with the Martino's Romas, which makes me think

that it might be either a seed of another variety accidentally slipped

into the packet, or a rare instance of a naturally produced hybrid

tomato. No matter where it came from, I like the unidentified

variety so far. It fruits just as prolifically as Martino's Roma

(although with smaller tomatoes), and is indeterminate, which means it

might end up giving us more tomatoes in the long run. The little

red roma does seem to be a bit more blight-prone (as you can tell by

how high up I've cut leaves on the stem), but once the rains slacked

off, the plant began to hold its own, unlike the first two varieties

profiled in this post. I'm saving

seeds and will try this variety out in more numbers next year.

In case you're curious

what that leaves us with, our regular tomato varieties are Martino's

Roma, Yellow Roma, Stupice, and some tommy-toe --- maybe we'll go back

to Blondkopfchen for next year? It's fun to try out new

varieties, but I'm glad I put most of my eggs in the old-standby basket.

Relocating

that copperhead snake

reminded me how that hillside seems more prone to wild mushroom growth.

We spotted this Amanita parcivolvata on our way

back, also known as a False Caesar's Mushroom.

It's unclear if these are

okay to eat. I won't be risking a taste test unless we get more

conclusive data.

The carving on this boundary

tree (which I'm pretty sure isn't really 200 years old) reminded me of

a story our mechanic's brother related this summer. He told us

that he remembered when a preacher lived in the old house that used to

stand in our core homestead area, and that folks walked in from all

directions to be married here. I found the tale interesting

because I'd wanted to get hitched at home, but knew that very few of

our friends and family would feel up to the short trek (about a quarter

of a mile through moderately rough terrain) from the parking area to

our trailer.

The carving on this boundary

tree (which I'm pretty sure isn't really 200 years old) reminded me of

a story our mechanic's brother related this summer. He told us

that he remembered when a preacher lived in the old house that used to

stand in our core homestead area, and that folks walked in from all

directions to be married here. I found the tale interesting

because I'd wanted to get hitched at home, but knew that very few of

our friends and family would feel up to the short trek (about a quarter

of a mile through moderately rough terrain) from the parking area to

our trailer.

Meanwhile, I've been

pondering how far is too far to hoof it because we want the Walden

Effect Annex to be

within walking or biking distance. We're currently looking at a

tract four miles away, up over a ridge and down the other side. I

suspect that a hundred years ago, this property would definitely count

as being within walking distance, but I'm not sure if I consider it

such. (The steep hill would make it a bear to bike, but I guess

you could coast down the other side.)

Of

course, if you went as the crow flies, the property is really only

about a mile and a half away, and if you followed the old roads (which

are now private property), it's more like two and a half miles.

When I visited England in 2000, I was impressed by the network of foot

paths that made it easy to get from village to village, remnants of a

time when everyone walked or rode a horse. The same sort of paths

still exist in our neck of the woods, but are no longer public

property, presumably since they weren't worth maintaining to car

standards.

Of

course, if you went as the crow flies, the property is really only

about a mile and a half away, and if you followed the old roads (which

are now private property), it's more like two and a half miles.

When I visited England in 2000, I was impressed by the network of foot

paths that made it easy to get from village to village, remnants of a

time when everyone walked or rode a horse. The same sort of paths

still exist in our neck of the woods, but are no longer public

property, presumably since they weren't worth maintaining to car

standards.

So what do you consider

walking distance? Presumably it depends on how hilly your terrain

is, and whether the roads are even safe to walk along. (We could

hike to our nearest town, but it would be along a country highway with

no room to walk outside the car lanes, so we don't risk it.) I'm

especially interested in hearing from the quarter of our readers who

reside outside the US --- is a seven mile walk par for the course in

India? Do you Brits really use your foot paths? How about

the large contingent of you in the Phillipines?

Exploring a bit further past

the Amanita

parcivolvata yielded a

large crop of fresh wild oyster mushrooms.

I'd like to report they were

yummy, but I think we found them a day or two late for gourmet results.

Too bad there's not a gizmo

that can detect when a log is in mushroom mode and transmit some sort

of FM signal back to base camp.

Now that we have a porch,

starting fall seedlings "inside" is much less fiddly than

previously. I set the flats

of broccoli, cabbage, and Brussels sprouts on the edge of the porch

where they'd get plenty of light, so I didn't have to worry about

legginess and hardening off to the scorching summer sun. And

since the flats were right next door to the hose and the floor is water

resistant, I could just sprinkle them lightly whenever I thought about

it.

Now that we have a porch,

starting fall seedlings "inside" is much less fiddly than

previously. I set the flats

of broccoli, cabbage, and Brussels sprouts on the edge of the porch

where they'd get plenty of light, so I didn't have to worry about

legginess and hardening off to the scorching summer sun. And

since the flats were right next door to the hose and the floor is water

resistant, I could just sprinkle them lightly whenever I thought about

it.

Having transplants makes

it even easier to fill gaps

in the summer garden with fall crops. After using up the

spots that had been home to problematic

tomatoes with

broccoli and cabbage, I had enough seedlings leftover to devote half a

dozen more beds to fall crucifers. I'm hoping for bountiful late

fall harvests to tide us over on fresh produce further into the cold

season.

These loppers stopped cutting

all the way through.

Closer inspection reveals the

edge to have bent over due to the hundreds of cuts we've made with it

over the last 7 years or so.

A few minutes of filing was

all it took to put a sharper edge on both cutting surfaces.

Even though you're not

supposed to poke around in the Warre hive more than once a year, you

are allowed to take off the lid and quilt and observe the layer of

burlap that covers up the bees' living quarters. You're not

exposing the colony to the outdoors, so there's no need for protective

equipment or a smoker as long as you stand behind the hive (always a

good idea) rather than in the bees' flight path. Saturday as I

was lazing around the yard, I decided to pop the hood and take a look.

Even though you're not

supposed to poke around in the Warre hive more than once a year, you

are allowed to take off the lid and quilt and observe the layer of

burlap that covers up the bees' living quarters. You're not

exposing the colony to the outdoors, so there's no need for protective

equipment or a smoker as long as you stand behind the hive (always a

good idea) rather than in the bees' flight path. Saturday as I

was lazing around the yard, I decided to pop the hood and take a look.

The first thing I noticed was

that the straw in my quilt box was starting to mold. The purpose

of the biomass in the quilt is to capture moisture coming out of the

hive while insulating the interior from climate extremes, so mold isn't

a very unusual occurrence there. However, discoloration generally

means its time to refresh the bedding, so I'll do that this week.

The first thing I noticed was

that the straw in my quilt box was starting to mold. The purpose

of the biomass in the quilt is to capture moisture coming out of the

hive while insulating the interior from climate extremes, so mold isn't

a very unusual occurrence there. However, discoloration generally

means its time to refresh the bedding, so I'll do that this week.

I carefully pried up the

quilt to take a look at the next layer down, and there I saw more of a

problem --- ants everywhere! A quick search of the internet

suggests that ants can be common in  Warre hives, and I see

why. The quilt creates a safe, mostly dry habitat that bees can't

get into to clean, but into which ants can often squeeze.

Presumably, the ants also pop down through the burlap between the quilt

and the hive and help themselves to the honey stores.

Warre hives, and I see

why. The quilt creates a safe, mostly dry habitat that bees can't

get into to clean, but into which ants can often squeeze.

Presumably, the ants also pop down through the burlap between the quilt

and the hive and help themselves to the honey stores.

Some beekeepers make a

wooden stand for their hive and place the feet in containers of water

or oil to keep the ants from climbing up. I may have to resort to

that, although I did see a skink in the quilt box that might have been

busy eating up the problematic ants. I'm curious to hear if

anyone else has found ants in their Warre hive quilt --- what did you

do about it?

Cut once down the middle and

then on each side at the 12 inch mark for some cheap and flimsy 8 foot

long shelf boards.

How cheap? A bit over a

dollar for each 8 foot section.

It only took Anna and me a few

minutes to rip each board.

--- Kathleen

I don't really think I'm

a professional, Kathleen, but I'll answer your question as best I

can. We do own a rototiller, although it hasn't been fired up in

years. Before I knew about no-till gardens, we started garden

patches by tilling

up the ground and shovelling the topsoil from the aisles onto the beds. (Now we start new

beds by simply laying down a kill mulch, which still raises the soil,

but not by as much.)

If you use the tilling method

of starting a new raised bed, I recommend against putting anything

along the edge to hold the soil in place. Yes, without sides, a

raised bed will turn from a rectangle to a hump over time, but it's a

pain to try to rip out perennial weeds that have gotten their roots

under logs or boards between your raised bed and the aisle. We've

gone both edged and edgeless, and I've ended up pulling out all of the

edging (except in our sloped blueberry patch, where I figure the

mini terraces that result are worth the effort of

weeding around logs).

pain to try to rip out perennial weeds that have gotten their roots

under logs or boards between your raised bed and the aisle. We've

gone both edged and edgeless, and I've ended up pulling out all of the

edging (except in our sloped blueberry patch, where I figure the

mini terraces that result are worth the effort of

weeding around logs).

I've compared

the pros and cons of grassy and mulched aisles previously. Each method has a

place, but in our situation, grass seems to be less work and money than

mulch. If you have a free source of mulch, though, and live

beside a road, you might be better off with wood chips in the aisles.

Rocks are something I

can't speak as knowledgeably about because we just don't have

any. I seem to remember that Mark found a rock last year, and he

was so excited, he called me over to look. But my educated guess

is that rocks aren't really a problem in a no-till garden. When

tilling and digging, stones mess up your tools, but if you're not doing

either, you'd think rocks would simply add micronutrients to the soil

and increase drainage.

The last unanswered part

of your question is about whether you can go straight to no-till in

problematic soil. For experimental purposes, I'm glad that parts

of our garden  have terribly heavy,

waterlogged clay soil while other parts have light, loamy soil

(although, of course, as a gardener, I wouldn't mind if my garden were

entirely the latter). Since I've worked with both soil types, I

can tell you definitively that tilling isn't going to help your clay

and might actively harm it, while no-till methods will improve the

ground slowly but surely. What clay really needs is lots of

organic matter to fluff it up, and the fastest way to get there is by

growing cover crops whenever possible. I

highly recommend oilseed

radishes as a fall

cover crop (you can plant them right now in most parts of the U.S.)

since they can handle awful soil and will show appreciable results in

the first year.

have terribly heavy,

waterlogged clay soil while other parts have light, loamy soil

(although, of course, as a gardener, I wouldn't mind if my garden were

entirely the latter). Since I've worked with both soil types, I

can tell you definitively that tilling isn't going to help your clay

and might actively harm it, while no-till methods will improve the

ground slowly but surely. What clay really needs is lots of

organic matter to fluff it up, and the fastest way to get there is by

growing cover crops whenever possible. I

highly recommend oilseed

radishes as a fall

cover crop (you can plant them right now in most parts of the U.S.)

since they can handle awful soil and will show appreciable results in

the first year.

I hope that helps get

you off on the right foot! In case you haven't read it, I'll plug

Weekend

Homesteader: May,

which includes a section on garden planning as well as one on kill

mulching. Some of the tips there on bed and path layout might

also be handy for you, even though you didn't specifically ask about

them. Good luck!

"As the farm began to take

form, Mark and I argued fiercely over everything. We discovered

that we had different desires, different visions for the farm. We

were both way too stubborn. We lost whole precious daylight hours

fighting over how to build a pig fence or whether the horses should

spend the night inside or out....

"As the farm began to take

form, Mark and I argued fiercely over everything. We discovered

that we had different desires, different visions for the farm. We

were both way too stubborn. We lost whole precious daylight hours

fighting over how to build a pig fence or whether the horses should

spend the night inside or out....

The most obvious theme

threaded through The Dirty Life is the effect that a farm

has on a relationship. I don't know whether it's harder to dive

in together as Mark and Kristin did and bump your way through the early

relationship years at the same time you're learning to grow things, or

whether it's worse to move to a farm when you're already in an

established relationship, only to learn the hard way that your dreams

don't match up with your spouse's as well as you'd thought.

Either way, I think the unnamed farmer who "said

that organic farms most commonly failed not from bankruptcy but from

burnout or divorce" was right on track.

On the other hand, if you can

figure out how to work together without killing each other, striving

with your partner toward a "clear joint purpose" can bring your

partnership to another level. One of my few complaints with The

Dirty Life is

that Kristin only gave us a few brief views into a happier future, like

this one:

On the other hand, if you can

figure out how to work together without killing each other, striving

with your partner toward a "clear joint purpose" can bring your

partnership to another level. One of my few complaints with The

Dirty Life is

that Kristin only gave us a few brief views into a happier future, like

this one:

This week's discussion

question is: if you've ever combined a romantic relationship with a

joint endeavor, how did you survive? Personally, I chalk all of

our relationship successes up to my husband, who always knows that it's

better to work an issue out than to get farm work done, no matter how

pressing the latter seems. Like the Kimballs, we often divide up

chores and we each have specialties that the other doesn't micromanage

very much, but we also try to plan bigger picture projects

together. How about you?

Those of you new the book

club might want to check out previous discussions that covered learning

that real food is imperfect and pacing

yourself in the early years. We'll be discussing the rest of

the book (three parts, but they're all short) next Wednesday, so I hope

you'll keep reading. And don't forget to hunt down Radical Homemakers, which we'll start

discussing on August 29.

Those of you new the book

club might want to check out previous discussions that covered learning

that real food is imperfect and pacing

yourself in the early years. We'll be discussing the rest of

the book (three parts, but they're all short) next Wednesday, so I hope

you'll keep reading. And don't forget to hunt down Radical Homemakers, which we'll start

discussing on August 29.

The

Weekend Homesteader provides

tips for becoming more self-sufficient one weekend at a time.

We had some trouble with the leaf

spring upgrade on the

golf cart.

It's possible we got a set

that was designed for a different model Club Car even though we ordered

them through a proper dealer. The problem was the springs would shift,

which would decrease the clearance and cause a rubbing sound.

Our local mechanic was able

to fix it by adding a large U-bolt to each side.

The

butternuts have taken to the forest garden like ducks to water.

The first photo shows the north side of the brush

pile and the second

shows the south side --- the butternuts have gone all the way up one

side and down the other!

The

butternuts have taken to the forest garden like ducks to water.

The first photo shows the north side of the brush

pile and the second

shows the south side --- the butternuts have gone all the way up one

side and down the other!

If the plants weren't

already starting to ripen their fruits and die back for fall, I might

worry about our naughy butternuts taking over the world.

We get a lot of ragweed

invading our perimeter.

It's a good thing neither of

us is allergic, but it doesn't take long before it grows high enough

to shade parts of the garden.

Wikipedia recommends pulling

up ragweed in the late spring when the roots are not as strong,

something we might try next year. Mowing is not good enough because if

just a half inch sticks out above the ground it will grow back even

stronger within 2 weeks of non freezing conditions.

I've touched on saving

tomato seeds before, but realized I'd never made a real post on the

topic. Since I like to save tomato seeds as early as possible in

the year to make it less likely  that fungi will hitchhike

into next year's garden via seed packets, I thought now would be a good

time to remind you all to get out there and save some seeds!

that fungi will hitchhike

into next year's garden via seed packets, I thought now would be a good

time to remind you all to get out there and save some seeds!

I wrote in great depth

about hybridization issues in Weekend

Homesteader: September,

so I won't repeat that information here. The short version is:

tomato-leaf tomatoes very seldom cross-pollinate, but currant tomatoes

and potato-leaf tomatoes do cross-pollinate with plants within the same

group. So, if your garden contains ten varieties of tomato-leaf

tomatoes, one potato-leaf tomato, and one currant tomato, you can save

seeds from all of them without getting unintentional hybrids.

Inbreeding depression (a

fancy name for the effect you see if you marry your brother) is much

less of a problem in tomatoes than in other plants, but I do try to

pluck at least two fruits from different plants in each variety to keep

genetic diversity as high as possible. Then I head back to the

kitchen to squeeze the guts out of each tomato, setting the flesh aside

to be turned into soup or sauce.

Tomatoes and cucumbers are relatively unique

because the seeds are enclosed in gelatinous sacs that need to be

fermented away before the seed can sprout. The process is a bit

smelly, but is otherwise very easy. Just add about an inch or two

of water to each small container of tomato seeds, then set it aside for

a week or so. Soon, you'll see mold forming on top of or in the

liquid, and the whole thing will start to stink. (Mark was

thrilled that I was able to ferment my tomato seeds on the porch this

year rather than on top of the fridge.) That's your sign that

your tomato seeds are ready to process and dry.

Tomatoes and cucumbers are relatively unique

because the seeds are enclosed in gelatinous sacs that need to be

fermented away before the seed can sprout. The process is a bit

smelly, but is otherwise very easy. Just add about an inch or two

of water to each small container of tomato seeds, then set it aside for

a week or so. Soon, you'll see mold forming on top of or in the

liquid, and the whole thing will start to stink. (Mark was

thrilled that I was able to ferment my tomato seeds on the porch this

year rather than on top of the fridge.) That's your sign that

your tomato seeds are ready to process and dry.

The simplest way to

separate seeds from moldy water is to add some more water, stir with a

spoon, let the tomato seeds settle back to the bottom of the container,

then pour off the foul liquid. I fill the container back up with

water two or three times to rinse off the seeds, then they're ready to

dry. If processed correctly, the seeds will look pale and fuzzy

within twenty-four hours, at which point you can put them in packets

for next year's garden.

A mild storm last night took

down one of our large walnut trees.

Nice of it to fall away from

the driveway instead of over it.

Anna did a quick root mass

autopsy which revealed a rotted out tap root. I'm guessing this will

provide enough firewood to keep us warm for a couple of months or more.

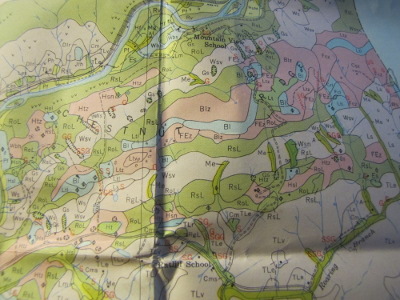

I've

been writing recently about some of the steps you should take to learn

about a property you're interested in before buying it --- a title

search, figuring

out where the boundaries are, and seeing

if the listed acreage is accurate. Assuming you're

planning to use the property for homesteading purposes, it's also

essential to get an idea of your soil type.

I've

been writing recently about some of the steps you should take to learn

about a property you're interested in before buying it --- a title

search, figuring

out where the boundaries are, and seeing

if the listed acreage is accurate. Assuming you're

planning to use the property for homesteading purposes, it's also

essential to get an idea of your soil type.

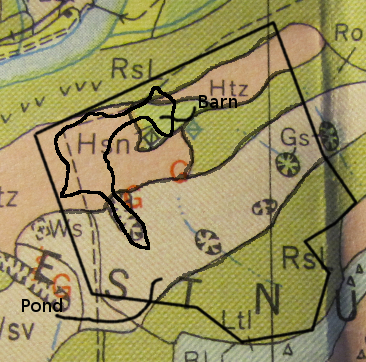

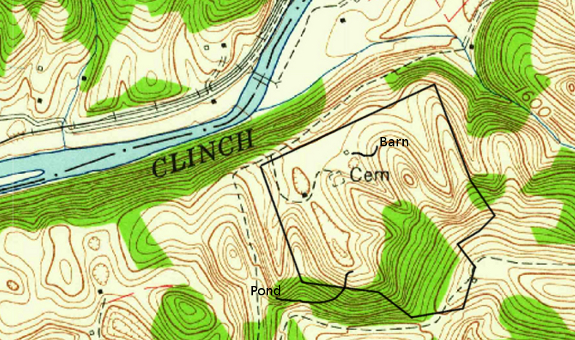

In the United States,

the NRCS has laboriously mapped every little pocket of earth, so you

can learn a lot by simply looking at maps. The modern way to do

this is to go to the Web

Soil Survey and find

your property using their interactive mapping tool, but that website

doesn't seem to be playing nice with my computer and I have an ancient

copy of my county's soil survey, so I decided to go old school.

(You can probably get a free copy of your region's soil survey at the

closest NRCS office, and some of you can download a

scanned version online.)

My county soil survey is an

ancient book with four maps stuck in a pocket inside the back

cover. The hardest part is locating your property on the soil

survey maps since they only include roads, houses from whenever the map

was produced (1951 in my case), and large rivers and streams. I

did this the easy way by photographing the relevant section of the map

and then scaling it in the Gimp until the shape of the nearby river fit

with the same river curve on my aerial photo. Since I had the

boundaries as a separate layer in my map file, I could soon see which

soil types were found on the property and how they related to the one

cleared field (the irregularly shaped blob in the northwest corner of

the image above).

My county soil survey is an

ancient book with four maps stuck in a pocket inside the back

cover. The hardest part is locating your property on the soil

survey maps since they only include roads, houses from whenever the map

was produced (1951 in my case), and large rivers and streams. I

did this the easy way by photographing the relevant section of the map

and then scaling it in the Gimp until the shape of the nearby river fit

with the same river curve on my aerial photo. Since I had the

boundaries as a separate layer in my map file, I could soon see which

soil types were found on the property and how they related to the one

cleared field (the irregularly shaped blob in the northwest corner of

the image above).

There's a key on the

side of the soil map that helps decipher the odd codes on the soil

survey. We live in a karst region, so there are lots of sinkholes

(the ovals with pointy teeth), and people have farmed our hilly land

too hard so there are gullys (red Gs). The other letters on the

map refer to the soil type: Hsn for the pink zone that includes most of

the current field, Ws for the paler area south of that, and so forth.

In our soil survey,

there's a separate fold out sheet of paper that turns the soil codes

into real words, then you can look up that soil type in the book to

learn much more about it. Here's what I discovered about the

cultivated areas on the property shown above:

|

|

Soil type |

Slope range |

Internal drainage |

Parent material |

Productivity and class |

Acres per animal unit |

|

Hsn |

Hagerstown silt loam; Rolling phase |

8-15 |

Medium |

Residual material from weathered limestone |

High; First |

1.5-2.4 |

|

RoL |

Rolling stony land (limestone material) |

3-30 |

Medium to slow |

|

Medium to moderately high; Fourth |

4.0-5.8 |

|

Htz |

Hagerstown stony silt loam; Steep phase |

15-60 |

Medium |

Residual material from weathered limestone |

Medium; Fourth |

2.3-3.3 |

|

Ws |

Westmoreland silt loam |

30-60 |

Medium |

Residual material from weathered limestone and shale mixed |

Medium; Fourth |

2.4-3.8 |

Of course, all of this

mapping should be taken with a grain of salt --- or rather, a shovel

and a day on the ground. For all I know, the prime topsoil in the

Hagerstown silt loam has all eroded away, but if it hasn't, that area

is clearly the best spot for vegetable gardening, while the poorer soil

on the east and south ends of the field could use some soil-improving

grazing. Taking a look at the real state of the ground is a good

thing to add to the list for a site visit!

It's

that time of year when we start saving eggs for another incubator

run.

I picked up some fancy

organic store bought eggs yesterday thinking they might make a decent

breakfast substitute.

When we first started out

with chickens I remember not being able to tell the difference between

our eggs and store bought.

There might be a lot of

things to explain the change, but I suspect our early chicken

tractor experiments didn't give the birds enough pasture and now

they spend all day foraging for worms and bugs.

These eggs still make a good

meal, but now I think I appreciate our pasture fed flock even more

thanks to this commercial taste comparison.

"Sooooooo,

I've read all of your posts on the potato

onions, and let's

say you've won me over. It looks like I'm getting these this

year. Have you finally cooked one? How does it taste?

Oniony? Garlicy?"

"Sooooooo,

I've read all of your posts on the potato

onions, and let's

say you've won me over. It looks like I'm getting these this

year. Have you finally cooked one? How does it taste?

Oniony? Garlicy?"

(This is also the reason why planting a big potato onion results in

several smaller onions the next year, while if you plant a small onion,

you get one big onion back.)

I've sometimes wondered if there was an easy way to automatically count

your chickens at the end of each day.

A little bit of searching

today turned up an exciting project that is working on using an

ordinary webcam

to identify and count chickens in a coop.

Most of the time chickens stay in a flock and when one goes in they all

follow, but not always. This system would be a nice addition to an automatic

coop door opener if the software could actually deliver on such a

lofty technical goal.

Mark and I both enjoy the

flavor of bean sprouts, so of course we wanted to produce our

own. First I experimented with urd

beans, which grew

beautifully and turned out to be semi-self-shelling, but were iffy to eat ---

the duds went rock hard and tended to get mixed in with the sprouts,

damaging teeth.

Mark and I both enjoy the

flavor of bean sprouts, so of course we wanted to produce our

own. First I experimented with urd

beans, which grew

beautifully and turned out to be semi-self-shelling, but were iffy to eat ---

the duds went rock hard and tended to get mixed in with the sprouts,

damaging teeth.

Since mung beans are the

variety you see in most stores, I figured they might be a better

option. Finding the seeds was tough...until I realized that I

could simply buy some beans for sprouting and germinate them in the

soil instead of in the kitchen.

I'm glad I changed varieties

because our mung beans have been even more productive than the urd

beans were. (It's not really a fair comparison, though, since the

urd beans got nibbled by deer and the mung beans didn't.)

I'm glad I changed varieties

because our mung beans have been even more productive than the urd

beans were. (It's not really a fair comparison, though, since the

urd beans got nibbled by deer and the mung beans didn't.)

The one flaw in mung

beans at the growth stage is that they tend to sprawl out across the

aisles, suggesting that a small trellis might come in handy for next

year's planting. Otherwise, mung beans are one of our easiest

crops since they don't seem to have any pests and just keep plugging

right along while the cucumbers wilt, the tomatoes blight, and the

green beans get eaten by beetles. (Don't worry, we're getting

good harvests of other vegetables despite these problems --- it's just

restful to look over at the mung beans after struggling with certain

other crops.)

I do have a couple of

tidbits to help those of you who want to try growing mung beans.

First is during the harvest phase --- try to pick ripe (black) pods

once a week if you live in a damp climate so none of the beans mold.

After picking, I just

spread the beans out on a tray for a couple of days to dry the dew off,

then shell them. Mung beans will self-shell like urd beans, but

the miniature explosions make me feel like I live at a shooting range,  and the beans tend to get

strewn around in all directions, so I generally end up taking the beans

out of the pods by hand. (Yes, I can shell beans while I read.)

and the beans tend to get

strewn around in all directions, so I generally end up taking the beans

out of the pods by hand. (Yes, I can shell beans while I read.)

The other tricky part

about growing sprouting beans is eating them. Luckily, mung beans

don't seem to produce the rock-like non-sprouters that urd beans do (or

maybe I've just gotten better at sorting them out during the harvest

stage). But you need room temperature conditions to get the beans

to sprout before they mold. I kept trying to sprout beans in the

winter, because that's when we crave fresh produce, but the truth is

that in our non-climate-controlled trailer, the warmer seasons are a

better time for sprouting.

We've been enjoying

eating up last year's mung beans, but this year's harvest is even

bigger --- two cups so far with more on the vine. Looks like I

need to get creative about cooking with sprouts.

Create

an Oasis with Greywater seems to be the primary text

available on

the subject, so if you want to deal with wastewater in an alternative

manner, you'll need to get your hands on a copy. The book is

self-published, but the only negative I can come up with is that the

interior layout isn't very enticing --- too little white space on the

page. However, I think that Art Ludwig chose the design

intentionally so he could fit 300 pages worth of information into a 144

page book, thus cutting down fewer trees and selling the book for a

more reasonable price.

Create

an Oasis with Greywater seems to be the primary text

available on

the subject, so if you want to deal with wastewater in an alternative

manner, you'll need to get your hands on a copy. The book is

self-published, but the only negative I can come up with is that the

interior layout isn't very enticing --- too little white space on the

page. However, I think that Art Ludwig chose the design

intentionally so he could fit 300 pages worth of information into a 144

page book, thus cutting down fewer trees and selling the book for a

more reasonable price.

That small caveat aside,

Create

an Oasis with Greywater is a masterpiece. The

fifth edition is completely polished, easy to read, and full of useful

information for everyone from the ramshackle DIYer (that's me) to folks

living in mansions who want to hire someone to create a high tech lawn

irrigation system connected to their washing machine outflow hose.

In case you've never run

across the term before, "greywater" is all of the waste water coming

from your house except from the toilet. The water flowing down

the drain of your kitchen sink is definitely not potable, but is

generally pretty low in harmful bacteria and can be easily and safely

treated with low tech options that irrigate your plants at the same

time. In addition to helping your plants, channeling your

greywater to a separate location from your blackwater means you

use less energy to treat the latter, which is good for the environment.

In case you've never run

across the term before, "greywater" is all of the waste water coming

from your house except from the toilet. The water flowing down

the drain of your kitchen sink is definitely not potable, but is

generally pretty low in harmful bacteria and can be easily and safely

treated with low tech options that irrigate your plants at the same

time. In addition to helping your plants, channeling your

greywater to a separate location from your blackwater means you

use less energy to treat the latter, which is good for the environment.

To make the best use of

greywater, you'll need to be careful with what you put down the drain

(something you should be doing anyway), and to understand your specific

site conditions and climate. The rest of this week's lunchtime

series will cover a few of the greywater treatment methods that

appealed most to me, but I highly recommend finding this book for

yourself if you want to delve deeper into greywater systems.

| This post is part of our Create an Oasis with Greywater lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

I tried out the new chainsaw

chaps today while we cut up some firewood.

They sort of feel like

wearing wet jeans with all the extra weight, and they hold in heat, but

the increase in safety feels worth the decrease in comfort.

August

is the month of the tomato on our homestead. Unless we have a

very dry summer (unusual for us), I spend almost a fifth of

my August garden time battling

the blight.

I've (mostly) learned not to

get my blood pressure up as the dead leaves progress up the stem, and

to simply make the best of the fruits our plants do ripen.

Inevitably, the blight wins, but not before we've filled our larder

with enough rich, red pulp to feed us until next year.

August

is the month of the tomato on our homestead. Unless we have a

very dry summer (unusual for us), I spend almost a fifth of

my August garden time battling

the blight.

I've (mostly) learned not to

get my blood pressure up as the dead leaves progress up the stem, and

to simply make the best of the fruits our plants do ripen.

Inevitably, the blight wins, but not before we've filled our larder

with enough rich, red pulp to feed us until next year.

Meanwhile, half my time

in the kitchen revolves around the

tomato too. This year, we've been pushing soups as hard as we

can,

since that seems to be our favorite kind of preserved bounty during the

cold months (and does triple duty, putting away green beans and corn as

well as tomatoes). This weekend's haul, though, was so extreme

that I

first pulled out the prettiest romas to slice in half and dry, made a

few gallons of soup, and then ended up with  a bowlful of leftover

tomatoes to turn into ketchup.

a bowlful of leftover

tomatoes to turn into ketchup.

Of course, the garden is

also churning out lots of other produce --- watermelons, cucumbers,

summer squash, basil, parsley, cutting celery (a new experiment for us

this year), mung

beans, sweet corn,

green beans, okra, Swiss chard, fall raspberries, and probably a few

other things I've forgotten. But tomatoes draw my attention the

way I've been told exposed breasts attract the male eye --- it's hard

to look at anything else when the plump, round orbs are on display.

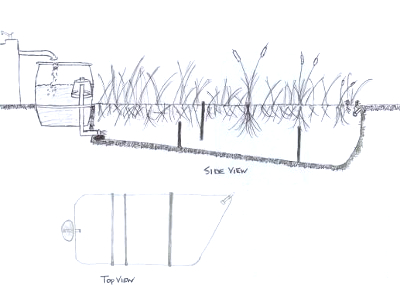

The

simplest type of greywater system is what Art Ludwig calls the drain

out back. In other words, you take the pipe from your sink or

bathtub and run it to an out-of-the-way location to leach

directly into the soil.

The

simplest type of greywater system is what Art Ludwig calls the drain

out back. In other words, you take the pipe from your sink or

bathtub and run it to an out-of-the-way location to leach

directly into the soil.

We only have running

water in one location in the house (the kitchen sink), and our original

treatment system

soon devolved into a drain out back when I didn't have enough wood

chips on hand to replace the mulch. As long as your outlet isn't

close to a stream or to a direct route into the groundwater (such as a

sinkhole), this low tech solution really isn't so bad. Yes, the

ground gets a bit swampy there, but the soil microorganisms make short

work of nutrients and germs in the water, and by the time the liquid

seeps down into the groundwater, it's pure. In most states, new

systems of this type are probably illegal, but even the regulators

don't really care as long as your system is grandfathered in and

doesn't bother your neighbors.

An alternative extremely low

tech solution is what Art Ludwig calls "landscape direct". We use

this technique by setting our wringer

washer in the middle of the yard and simply dumping the used wash water

into the ground. A more elegant incarnation is the bathing garden

illustrated in Create

an Oasis with Greywater,

which consists of a raised, cobbled mound on which you shower,

underlain by sand to expedite drainage, and surrounded by plants to

soak up the water.

An alternative extremely low

tech solution is what Art Ludwig calls "landscape direct". We use

this technique by setting our wringer

washer in the middle of the yard and simply dumping the used wash water

into the ground. A more elegant incarnation is the bathing garden

illustrated in Create

an Oasis with Greywater,

which consists of a raised, cobbled mound on which you shower,

underlain by sand to expedite drainage, and surrounded by plants to

soak up the water.

The main problem with

low tech systems like these is loss of

efficiency. If you live in a very dry climate, every drop of

water is precious, so it's worth spending a bit more effort to ensure

your greywater ends up feeding plants. Stay tuned for the rest of

the lunchtime series (picking back up Thursday after our regular book

club discussion) for slightly higher tech, and more efficient,

greywater options.

| This post is part of our Create an Oasis with Greywater lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

We decided to dig up our

wineberry patch today.

The berries are beyond

delicious, but if they decided to bloom we typically only got enough to

fill a small bowl.

It was a tough decision, but

deleting it gives us a new spot to try something different. The goal is

to find varieties that can handle our climate without being

temperamental.

Other than "tomato, tomato,

tomato!", the

primary topic on my to-do list this month is fall

cover crops.

I've learned that although I can seed oilseed

radishes anytime

between August 1 and September 7, every week that passes lowers the the

amount of biomass produced appreciably. That's why I wander

through the garden with an eagle eye throughout the early and middle

parts of August, looking for things to be pulled out.

Other than "tomato, tomato,

tomato!", the

primary topic on my to-do list this month is fall

cover crops.

I've learned that although I can seed oilseed

radishes anytime

between August 1 and September 7, every week that passes lowers the the

amount of biomass produced appreciably. That's why I wander

through the garden with an eagle eye throughout the early and middle

parts of August, looking for things to be pulled out.

For example, giving

away excess cucumbers

was a lot of fun in July. But by August, it seems to make more

sense to rip out still-producing cucumber plants and scatter radish

seeds in their place. Sweet corn gets cut to the ground as soon

as I pluck the least ear, and next week I'll be pulling out dead

butternut squash and watermelon vines. (I may remove some living

summer squash plants too --- we've dried our winter quota and can't eat

all of the fruits being produced.)

I like planting fall cover

crops because they produce organic matter at an off-time for the

garden. We've got a few more beds of kale and lettuce to plant

along with a lot of garlic, but other than that, any beds that come

open from here on out are going to be sitting around twiddling their

thumbs until spring. I'd far rather put a cover crop there and

capture winter sunlight than let that solar radiation go to waste.

I like planting fall cover

crops because they produce organic matter at an off-time for the

garden. We've got a few more beds of kale and lettuce to plant

along with a lot of garlic, but other than that, any beds that come

open from here on out are going to be sitting around twiddling their

thumbs until spring. I'd far rather put a cover crop there and

capture winter sunlight than let that solar radiation go to waste.

But how much good do

cover crops do? The amount of organic matter produced by a cover

crop will depend on a lot of factors, such as your soil conditions and

planting time, but I dug up these figures for optimal dry matter

production per acre for my three favorites:

- Oilseed radish --- 7,000 pounds per acre

- Buckwheat --- 6,000 pounds per acre

- Fall-planted oats --- 4,000 pounds per acre

To put that in

perspective, adding half an inch of compost to your garden per year

requires about 68,000 pounds. Roughly half of that is water, so

the bare-minimum level of top-dressing in an organic garden provides

34,000 pounds of dry compost per acre. Cover crops don't approach

that figure, but providing a fifth of your annual organic matter with

no shoveling is nothing to sneeze at.

The big question is ---

how much of the organic matter added actually turns into humus and

stays in your soil, and how much is quickly degraded? As you may

or may not realize, the soil food web is constantly working on breaking

down organic matter, which is a good thing since the output feeds your

plants. But those microorganisms do work counter to my goal of

building soil structure.

In fact, if you don't add

anything to your soil (especially if you till), your soil's organic

matter content will decline each year. An

interesting study showed that organic matter levels of soil increased

from 5.2% to 5.5% when 30 tons of dairy manure were applied per acre

for eleven years, stayed steady at an application rate of 20 tons per

acre, and dropped to 4.8% at 10 tons of manure per acre.

In fact, if you don't add

anything to your soil (especially if you till), your soil's organic

matter content will decline each year. An

interesting study showed that organic matter levels of soil increased

from 5.2% to 5.5% when 30 tons of dairy manure were applied per acre

for eleven years, stayed steady at an application rate of 20 tons per

acre, and dropped to 4.8% at 10 tons of manure per acre.

Meanwhile, in the cover

crop world, experts suggest that woodier

debris is more likely to turn into humus (a stable form of organic

matter) than succulent plant matter is. That's why I wait to kill

buckwheat until it's in full bloom, and why tough-stalked oats may

actually produce more long-term organic matter than oilseed radishes

do. Perhaps pulling mature oilseed radishes and composting them

would be a better way of capturing their full potential than letting

them rot in the ground?

I may try that eventually, but for now, I'm quite happy with the

ever-darkening soil in the beds that I commit to winter cover crops.

When we first meet Mark

Kimball in The Dirty Life, he forces Kristin to live

in a fully wired house without turning on the electricity (to her

chagrin). A year later, they have a freezer and fridge.

Similarly, they plan their farm to be cultivated with horse power, but

do have a backup tractor that sees some use.

When we first meet Mark

Kimball in The Dirty Life, he forces Kristin to live

in a fully wired house without turning on the electricity (to her

chagrin). A year later, they have a freezer and fridge.

Similarly, they plan their farm to be cultivated with horse power, but

do have a backup tractor that sees some use.

Choosing your own level

of appropriate technology is an important but difficult task for most

homesteaders. Do you carry the water from the creek or pay the

startup costs and electricity bill to irrigate your crops? Do you

try each time-saving device you read about in Mother

Earth News, or do

you remember that energy is used and waste produced for every item you

buy?

On our own homestead,

Mark's a gadget guy and I'm a skinflint, so we often have to negotiate

compromises. I'm curious to hear from other homesteaders --- how

do you decide what consists of appropriate technology? When you

were reading The

Dirty Life, did you end up dreaming of

a farm with draft horses, or did the runaway horse episode cure you of

that romantic notion in a heartbeat?

Those of you new the book

club might want to check out previous discussions that covered learning

that real food is imperfect, pacing

yourself in the early years, and working

together without killing each other. Since we've come to the

end of The Dirty Life,

now would also be a good time to comment with anything that really

jumped out at you from the book that I haven't mentioned here.

We'll take a week off, then will jump into Radical

Homemakers on August 29.

Those of you new the book

club might want to check out previous discussions that covered learning

that real food is imperfect, pacing

yourself in the early years, and working

together without killing each other. Since we've come to the

end of The Dirty Life,

now would also be a good time to comment with anything that really

jumped out at you from the book that I haven't mentioned here.

We'll take a week off, then will jump into Radical

Homemakers on August 29.

The

Weekend Homesteader provides

tips for becoming more self-sufficient one weekend at a time.

Our Chicago

Hardy Fig will be 2 years

old this November.

Anna predicted it would be

2012 when we would first see some fruit and it looks like there should

be a respectable amount depending on how soon our first major frost

happens.

Neither of us have tasted

fresh figs and we have been looking forward to fig harvest day since we

saw the first buds.

Last winter, I played around

with making nest sites to attract

native pollinators.

I figured there wasn't really much need since we have plenty of habitat

just a stone's throw away in the woods, but I was curious to see if

anyone would move in anyhow. Sure enough, several native bees

took advantage of the in-garden accomodations!

Last winter, I played around

with making nest sites to attract

native pollinators.

I figured there wasn't really much need since we have plenty of habitat

just a stone's throw away in the woods, but I was curious to see if

anyone would move in anyhow. Sure enough, several native bees

took advantage of the in-garden accomodations!

But first, I should tell

you what didn't work. The insects ignored my large and small

nest blocks, which I

figure is probably my own fault. The books recommend drilling the

holes with a very sharp bit, and I didn't have one  on hand, so the interiors of

the potential nest chambers were full of burrs of wood.

Meanwhile, I put all three of my experimental nest blocks in exposed

locations, meaning that rain could potentially drip in, which probably

also made the cavities less enticing.

on hand, so the interiors of

the potential nest chambers were full of burrs of wood.

Meanwhile, I put all three of my experimental nest blocks in exposed

locations, meaning that rain could potentially drip in, which probably

also made the cavities less enticing.

On the other hand, my stem

bundles saw a lot of

activity. You can tell if a native bee has moved into a nest

because you'll notice dried mud plugging the end of the cavity, perhaps

with a round hole in the mud if the inhabitants have already grown up

and flown away. The photo below illustrates the difference

between used, unused, and still occupied stems, all in the same bundle.

Since only about a third

of my stem bundles were used, I got a good idea of which sites the

insects preferred. Exposure to the elements kept bees away from

all except one stem in the peach tree hotel, but many more of the ones under

the awning of the wood stove roof showed signs of use. Bamboo

seemed to be preferable to drilled-out elderberry twigs, probably again

because my drill bit wasn't sharp enough to provide an interior as

smooth as the natural bamboo walls. It's also possible that the

bees liked the more solid ends created by the bamboo stem joints

compared to the twigs that I blocked off with mud.

I'd be curious to hear

from readers who have experimented with building nest habitat for

native pollinators. What worked and didn't work for you?

Art Ludwig's favorite

method of using greywater in the landscape is called the mulch

basin. Installation can be nearly as simple as creating a drain

out back, with the

addition of digging a donut around your tree, piling the soil on the

outside to form a moat, and filling the depression with wood chips (and

your grewater outlet). The soiled water goes directly to a

thirsty plant, who also benefits from the nitrogen content of kitchen

scraps and other debris.

Although the mulch basin is

much more efficient than the drain out back, you also have to go to

more short and long term effort to make the greywater system work

properly. Create

an Oasis with Greywater walks you through building

branched systems to channel water to multiple trees and ensure no

single plant gets swamped, but even if you plan watering amounts

accurately, you still need to make sure the plant being watered can

handle daily infusions of dishwater.

Although the mulch basin is

much more efficient than the drain out back, you also have to go to

more short and long term effort to make the greywater system work

properly. Create

an Oasis with Greywater walks you through building

branched systems to channel water to multiple trees and ensure no

single plant gets swamped, but even if you plan watering amounts

accurately, you still need to make sure the plant being watered can

handle daily infusions of dishwater.

Of the greywater

tolerant plants Ludwig lists, very few live in our climate and none of

those are active in the winter. That means you need to have an

alternative greywater system in place during the dormant season, which

I'll talk about in tomorrow's post. Meanwhile, if you'd like to

make a mulch basin to put your greywater to use in the summer,

potentially useful temperate-climate plants include blackberries,

elderberries, currants, bamboo, and (to a lesser extent---be careful of

waterlogging) peach, plum, apple, pear, and quince. Those of you

who live in California (like Ludwig does) will want to start with

bananas and branch out into mangos, avocados, citrus, pineapple guava,

and figs.

The final issue with the

mulch basin is that it requires annual maintenance. Ludwig

recommends redigging your moat walls every year or two, which sounds

like effort that might not quite happen on our farm. (I'm not so

sure it would hurt to just let the tree get its bonus water close to

the trunk for its entire life, though.) On the other hand, I've

been hitting more than missing with my hugelkultur

tree mound expansions,

so maybe expanding a mulch basin would happen too.

The final issue with the

mulch basin is that it requires annual maintenance. Ludwig

recommends redigging your moat walls every year or two, which sounds

like effort that might not quite happen on our farm. (I'm not so

sure it would hurt to just let the tree get its bonus water close to

the trunk for its entire life, though.) On the other hand, I've

been hitting more than missing with my hugelkultur

tree mound expansions,

so maybe expanding a mulch basin would happen too.

I'm curious to hear from

anyone who's tried a mulch basin, but especially from those who live in

an area with winter. What would you add to the pros and cons I've

listed above?

| This post is part of our Create an Oasis with Greywater lunchtime

series.

Read all of the entries: |

The new 12

amp circular saw is just under 3 months old and is already acting

like it wants to retire. The problem is an issue of needing to tighten

the blade every few cuts. It's possible it may have been over tightened

which might damage the bearings.

To be fair I think we under

estimated our usage and should have chosen the next level up.