archives for 07/2012

This

has been a deer-filled week, but not a single nibble in the

garden...yet. First, it became abundantly clear that the

last week of June was when fawns were being born in 2012. Bradley

saw a deer in labor down by the creek early in the week, and when I

walked that way the next day, I found hoofprints the size of a

thumbprint in the little bit of mud that has survived the drought.

This

has been a deer-filled week, but not a single nibble in the

garden...yet. First, it became abundantly clear that the

last week of June was when fawns were being born in 2012. Bradley

saw a deer in labor down by the creek early in the week, and when I

walked that way the next day, I found hoofprints the size of a

thumbprint in the little bit of mud that has survived the drought.

Thursday, we were all

working outside when a bleat like the cry of a goat made us drop our

tools in puzzlement. We don't have neighbors with goats, but the

more avid hunter in our midst (that's Bradley, in case you haven't

guessed) knew immediately that the sound was the call of a frightened

fawn. Sure enough, two does were down past the barn and a fawn

was fleeing in the opposite direction, startled by Lucy. The

mother deer started to come at Lucy with her hooves, but our smart dog

had too much sense to engage and just raced around in excitement.

I'm

pretty sure that fawn eventually made it back to its mother after Lucy

lost interest, but Friday Lucy showed up with a fawn hindquarter

between her jaws. From reading too many mystery novels, I knew to

look at the size of the maggots on the flesh, which told me that the

fawn had probably died before the barn bleater was sighted.

Again, our hunting advisor had the best analysis of the situation ---

the fawn had probably been caught in the machine when our neighbor

hayed his field a few days before.

I'm

pretty sure that fawn eventually made it back to its mother after Lucy

lost interest, but Friday Lucy showed up with a fawn hindquarter

between her jaws. From reading too many mystery novels, I knew to

look at the size of the maggots on the flesh, which told me that the

fawn had probably died before the barn bleater was sighted.

Again, our hunting advisor had the best analysis of the situation ---

the fawn had probably been caught in the machine when our neighbor

hayed his field a few days before.

All of this was minor

compared to the excitement Saturday morning. I rolled out of bed

and settled into my usual spot on the couch with a view of the entire

front garden and blueberry patch...and a deer! The first invader of

the garden in 2012!

On closer inspection, it

turned out that the doe had injured herself jumping over the fence in

the night. She was limping around our inner perimeter looking for

a way out, but was unable to jump the fence with her broken or sprained

leg.

I spent too long thinking

through my options, so disaster struck. First, it ran through my

head that if the deer had gotten into the garden once, she'd be

back. Plus, how long would she last in the wild with an injured

leg? Might as well put her out of her misery (and eat her).

I spent too long thinking

through my options, so disaster struck. First, it ran through my

head that if the deer had gotten into the garden once, she'd be

back. Plus, how long would she last in the wild with an injured

leg? Might as well put her out of her misery (and eat her).

On the other hand, what

if she had a fawn like all of the other does I'd seen recently?

Did I want the poor baby to starve? (Well, maybe I did --- after

all, we're badly overpopulated with deer in our region.) And, of

course, it's not hunting season, so shooting the deer in my garden

would be illegal. Finally, we're in for record heat this weekend,

so processing would have to be fast.

Before I could make up

my mind, Lucy made up hers. The deer had seen me and gotten

alarmed, battering herself against the fence behind our water tank, and

our usually even-tempered dog ran up there and actually went straight

for the deer's throat! It was like a scene out of Call

of the Wild, and

I was terrified the deer would slice Lucy open with her hooves.

(I don't have any relevant photos, so Huckleberry is recreating the

Battle of the Deer for your viewing pleasure, using his brother as a

prop.)

To protect our beloved

dog, I would have shot the deer in a heartbeat, but I'm simply not a

good enough marksman to fire into a tangle of dog and deer and think

I'd only hit the latter. Plus, there was our precious water

tank inches away

from the melee. While I hollered ("Lucy! No!"), the deer

burst through the fence and got away.

The moral of the story is: I

need to work on my target practicing and decision making. Or

rather, I need to think through issues like this before they show up in

my garden at 6 am on a Saturday. Am I willing to shoot a deer in

the garden out of hunting season? What if she probably has a

fawn? For the hunters among you, what would you do?

The moral of the story is: I

need to work on my target practicing and decision making. Or

rather, I need to think through issues like this before they show up in

my garden at 6 am on a Saturday. Am I willing to shoot a deer in

the garden out of hunting season? What if she probably has a

fawn? For the hunters among you, what would you do?

(Huckleberry says he'd

take the deer down and gnaw on its bones!)

The woodshed

expansion project got

wrapped up this week.

The woodshed

expansion project got

wrapped up this week.

It kind of hurts to think of

a winter fire on a day like today, but it's a warm feeling knowing

we've got a solid, long term solution to keeping our firewood dry.

I'd guess once we get it full

it might last 2 or 3 winters depending on the temperature.

Are you looking for the

world's tastiest tomato? (Who isn't?) If so, a

new study suggests

you should choose the uglier varieties that don't turn evenly red.

Are you looking for the

world's tastiest tomato? (Who isn't?) If so, a

new study suggests

you should choose the uglier varieties that don't turn evenly red.

If your full-grown but

green tomatoes look like the ones pictured in this post, you're in

luck. The darker green top means that portion of the tomato is

full of chloroplasts, busy spinning straw into gold....er, I mean,

sunlight into sugars.

Supermarket tomatoes, in

contrast, have been bred to ditch the dark green top.

Agrobusinesses have found that consumers are more prone to select a

tomato that's a solid red color rather than having a tinge of green

around the stem.

Unfortunately, the same

gene that makes the tomatoes turn red uniformly means they don't get

that extra flavor boost. So, pretty tomatoes = insipid

flavor. Of course, there

are other factors that lead supermarket tomatoes to "taste like crap" (in the words of one of our

readers), but it's interesting to find out that variety selection does

matter.

(Yes, we have eaten two

remarkably early tommy-toe tomatoes. No, there's still no hint of

color on our larger plants.)

I figured we all deserved a

break from hard-to-parse books during the dog days of summer. So

our second selection will be a light and fun memoir.

I figured we all deserved a

break from hard-to-parse books during the dog days of summer. So

our second selection will be a light and fun memoir.

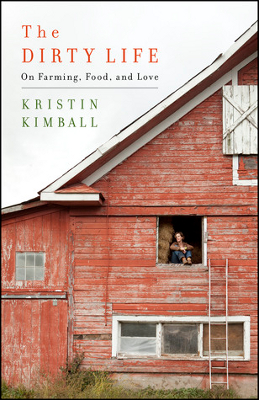

The

Dirty Life: A Memoir of Farming, Food, and Love follows a back-to-the-land

couple who eventually developed perhaps the most interesting CSA currently in

existence. Here's a description of Essex farm (from the author's website):

We currently farm 600 acres and feed 222 members. We are powered by fifteen solar panels, nine draft horses, ten full-time farmers, and three tractors. We do not use synthetic fertilizer, herbicide, or pesticide. Our animals eat feed we’ve grown ourselves or local hay and local, certified organic grain.

The all-you-can-eat membership price for 2012 is $3300 per year for the first adult in a household, and $2900 for the second adult, with a $400 discount for each additional adult. Children over 3 are $100 per year of age (e.g., a five-year-old is $500 for the year, a seven-year-old is $700, etc.).

It's an intriguing

model, and my understanding is that Kristin Kimball writes about the  path to building their farm

in an easy-to-read and entertaining manner. So, head to your

library or book store and pick up a copy! We'll begin discussions

on July 25 (with more information about how much of the book we'll

discuss in the first chunk once I have a copy in my hands). I

hope that even those of you who've been driven away by Thoreau's

excessively long sentences will return to the fold!

path to building their farm

in an easy-to-read and entertaining manner. So, head to your

library or book store and pick up a copy! We'll begin discussions

on July 25 (with more information about how much of the book we'll

discuss in the first chunk once I have a copy in my hands). I

hope that even those of you who've been driven away by Thoreau's

excessively long sentences will return to the fold!

My

paperback is

currently at the printer, so those of you who have preordered will have

a copy before too long! Thanks to everyone who has bought it

sight unseen.

We had a power outage last

night. It started around midnight and lasted till about 9 am.

The last time we used our back

up generator was over 2 years ago, and I forgot to run all the fuel

out of it when we were finished which created a situation where the

engine would begin to start and then quit.

It just so happens we were

asking our helper Bradley about this problem last week and his advice

was to drain the fuel and replace the spark plug which most likely got

fouled up due to my neglect.

I almost got up in the middle

of the night to see if I could extract the old plug and maybe swap it

with one from the lawn mower due to the high temperature, but felt like

it would go better in the light of day. Funny how the power came back

on just as I got the old plug removed this morning. With any luck we'll

remember to pick up a fresh spark plug tomorrow so we can be ready if

the power goes out again.

I adore keeping track of the

weather, but I've been on strike for the last two years. You see,

the little digital max/min thermometers I'd been buying kept keeling

over after six months or a year, and I'm just not keen on throwaway

products.

I adore keeping track of the

weather, but I've been on strike for the last two years. You see,

the little digital max/min thermometers I'd been buying kept keeling

over after six months or a year, and I'm just not keen on throwaway

products.

I think I've finally

found the solution --- an

analog thermometer that still records maximum and minimum temperatures, for the same price as those

disposable digitals. Unless I drop it or hit it with a brick, I

can't think what might go wrong.

The Sper Scientific

thermometer is so simple it's ingenious. The column of mercury is

bent into a U-shape so that you can read the temperature both on the

right and on the left. Each side of the column also has a

colored, magnetized something-or-other inside the tube, so when the

temperature increases (on the max side) or decreases (on the min side),

the mercury pushes the colored marker in front of it. The marker

doesn't retreat to follow the mercury when the latter shrinks back

down, so you're left with a reminder of what the maximum or minimum

temperature was. Then you use a little magnet (attached to a

string so you don't lose it) to pull the markers back down onto the top

of the mercury column, resetting the maximum and minimum recordings.

Reading the thermometer does

take a bit of getting used to. First, if you're accustomed to

Fahrenheit, you have to remember to read the small numbers. And

you also have to realize that the numbers on the minimum (left) side go

from low numbers at the top to high numbers at the bottom rather than

vice versa. Finally, the markers only delineate two degree

intervals, so you won't get the same precision you see in a digital

thermometer.

Reading the thermometer does

take a bit of getting used to. First, if you're accustomed to

Fahrenheit, you have to remember to read the small numbers. And

you also have to realize that the numbers on the minimum (left) side go

from low numbers at the top to high numbers at the bottom rather than

vice versa. Finally, the markers only delineate two degree

intervals, so you won't get the same precision you see in a digital

thermometer.

But I don't mind a

slight learning curve if I've finally found a thermometer that will go

the distance. We got our new thermometer up and running just in

time to record last week's crazy temperatures --- a low of 42 one

night, followed soon thereafter by three days that hit 102. Maybe

it would have been less painful if I didn't know how hot it was?

I never heard back from four

of our Egyptian

onion winners.

So this is the last call for Barb, Monica, JT, and Stan --- please drop

me an email with your mailing address ASAP if you'd like your onions!

I never heard back from four

of our Egyptian

onion winners.

So this is the last call for Barb, Monica, JT, and Stan --- please drop

me an email with your mailing address ASAP if you'd like your onions!

Since I suspect some or

all of those winners may have wandered away and won't check back, I'm

also selecting four runnersup. Kerry, Sharon, Brian, and Carmen

--- if I get your email before I hear from the original winners, I'll

send the box of onions to your garden instead.

Finally, if you're still

itching to win something, our 2012

chicken photo contest

is up and running. We're giving away $300 worth of waterers this

year as a thank you to all of our customers. Stay tuned to our chicken blog to see some of the best

entries as they come pouring in.

We got a really nice summer

shower this afternoon at exactly the half way point when our helper

Bradley was replacing the other

front wheel bearing on

the golf cart.

He didn't want to leave with

it half way done, which is why he's doing a turtle impersonation in the

picture above.

I

think we've finally got our garlic planting amount figured out. We used

20 pounds of garlic in 2010, so when our 2011 crop came

in over quota, I gave the excess away. Sure enough, when the time

came to clean

and bag this year's garlic, we were down to the last

handful of the previous year's bulbs in the kitchen --- perfect!

I

think we've finally got our garlic planting amount figured out. We used

20 pounds of garlic in 2010, so when our 2011 crop came

in over quota, I gave the excess away. Sure enough, when the time

came to clean

and bag this year's garlic, we were down to the last

handful of the previous year's bulbs in the kitchen --- perfect!

Of course, our garlic

continues to adapt to our climate, so despite cutting back the number

of beds planted last fall (to twelve), I still ended up with 29.5

pounds of garlic. About half of that amount has sprouted and won't last too long, but

since I use a lot of our annual garlic supply during the summer months

(in soups, Hollywood

sun-dried tomatoes,

pizza sauces, etc.), I suspect the sprouted garlic will get eaten up

before it goes bad.

Even though I really

should cut back our planting this fall to take into account the extra

productivity from our acclimatized bulbs, I think I'm going to stick to

the same number of garden beds as last year. It's nice to have a

bit extra to give away, and Huckleberry seems to have developed a taste

for the crop....

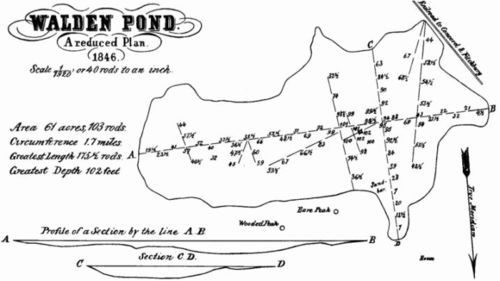

"While men believe in

the infinite some ponds will be thought to be bottomless," wrote

Thoreau. Then he spent the remainder of chapter 16 telling how he

surveyed the bottom of Walden pond.

Not only did Thoreau

determine that the body of water did indeed have a bottom (and no "vast

holes 'into which a load of hay might be driven'"), the chapter also

walked us through an excellent example of the scientific method.

Thoreau started by using keen observation to develop a hypothesis:

Step two of the

scientific method was using this observation to come up with a

hypothesis --- in this case, that the deepest spot in any pond can be

pinpointed using the method above. Next, Thoreau set up an

experiment to test his hypothesis. He used a map to estimate

where he thought the deepest point in another pond should lie, then

surveyed that pond and found his estimate close to the mark.

Of course, Thoreau would

have needed to survey quite a few more ponds to thoroughly test his

hypothesis. But it's handy to be reminded that deductive

reasoning is a very important skill to have, especially if you're a

homesteader trying to partner

with the natural world. Why are the bean beetles so much

worse than they've been in previous years? Is your neighbors'

advice spot on or is it an old wives' tale? If I were building a

curriculum for homesteaders to be, deductive reasoning would be

presented in week one.

If you're new to the book

club, you might want

to check out the thought-provoking comments on

chapter

1, chapter

2, chapters

3 and 4, chapters

5 and 6, chapters

7 and 8, chapters

9 and 10, chapters

11 and 12, and chapters 13 and

14. We'll

be discussing the last two chapters of Walden next week, and will then

be taking a week off before diving into The

Dirty Life. Don't forget to start hunting down a copy of the

next book (which is a much lighter read, I promise) ASAP.

If you're new to the book

club, you might want

to check out the thought-provoking comments on

chapter

1, chapter

2, chapters

3 and 4, chapters

5 and 6, chapters

7 and 8, chapters

9 and 10, chapters

11 and 12, and chapters 13 and

14. We'll

be discussing the last two chapters of Walden next week, and will then

be taking a week off before diving into The

Dirty Life. Don't forget to start hunting down a copy of the

next book (which is a much lighter read, I promise) ASAP.

Our recent golf

cart modifications helped to make tank moving day a smooth and enjoyable

process.

Thanks to the new

barn roof we plan to begin capturing rain water with most of the

tanks.

You'd think that a golf cart

pickup bed built by committee would be terrible, but you'd be wrong.

You'd think that a golf cart

pickup bed built by committee would be terrible, but you'd be wrong.

When the time came to

replace the decaying, two

year old structure,

we turned the project over to Bradley...with caveats. Usually, we

let him do whatever he wants (with results better than either of us

could have imagined), but Mark and I had spent a lot of time with the

old pickup bed and we each wanted some changes made.

Mark asked for the bed

to be light and durable --- he didn't want the weight of the bed to

reduce how much we could haul, and he did want the structure to last

more than two years. Meanwhile, I wanted the golf cart pickup bed

to be larger and to have higher sides. A tall order, but Bradley

came through with flying colors.

The first step was to

take apart what remained of the old bed. We love using screws

because they make it easy to change your mind about a project without

buying new  materials, but these screws

had been banged around so much, they weren't removable with the

drill. Enter Bradley's favorite tool --- the circular saw.

(Yes, we went out and bought him a second copy to live on our farm so

he didn't have to lug his through the alligator swamp repeatedly.)

materials, but these screws

had been banged around so much, they weren't removable with the

drill. Enter Bradley's favorite tool --- the circular saw.

(Yes, we went out and bought him a second copy to live on our farm so

he didn't have to lug his through the alligator swamp repeatedly.)

Mark's method of

attaching the previous bed to the frame of the golf cart passed muster,

so Bradley left it as is and simply built on top. He framed up

the base of the bed with treated two by fours similar to the way you'd frame the

floor of a house --- this method will ensure the bed is very durable,

while also allowing it to extend further beyond the body of the golf

cart.

A sheet of plywood on top

formed the floor of the bed, then Bradley went to work on the

walls. He modeled these after the slatted sides on fancy versions

of a kid's red wagon, which allowed him to extend the walls higher

without adding much additional weight. Since we haul biomass in

five gallon buckets, there's no problem with manure or wood chips

slipping out the sides, but Bradley did add a slat right against the

bed of the golf cart so nothing small will roll out.

A sheet of plywood on top

formed the floor of the bed, then Bradley went to work on the

walls. He modeled these after the slatted sides on fancy versions

of a kid's red wagon, which allowed him to extend the walls higher

without adding much additional weight. Since we haul biomass in

five gallon buckets, there's no problem with manure or wood chips

slipping out the sides, but Bradley did add a slat right against the

bed of the golf cart so nothing small will roll out.

For even spacing, Bradley

used a scrap piece of two by four to support the slats while screwing

them in place. (I could have helped, but I was busy with the

camera, and Mark was in town mailing chicken waterers.)

For even spacing, Bradley

used a scrap piece of two by four to support the slats while screwing

them in place. (I could have helped, but I was busy with the

camera, and Mark was in town mailing chicken waterers.)

Bradley went home and

Strider checked out the work in progress. "Perfect!" he told

me. "I can watch the dog house but Lucy can't get me!"

The next day, Bradley

came back and didn't get annoyed when we said, "We love what  you've done, but...."

The canopy for the golf cart has weird spurs sticking back into the

pickup bed area, which were originally used to attach straps to hold

golf club bags in place. But these spurs were likely to get in

the way of our serious hauling.

you've done, but...."

The canopy for the golf cart has weird spurs sticking back into the

pickup bed area, which were originally used to attach straps to hold

golf club bags in place. But these spurs were likely to get in

the way of our serious hauling.

"Not a problem," replied

Bradley. He took back off the bed and sides (ah, the glory of

screws!), removed the canopy supports, and replaced them with two by

fours. Then he put it all back together and added the tailgate,

made on the same principle as the sides but with some two by twos for

additional structural support.

Speaking of structural

support, the photo below shows the diagonal braces Bradley added

underneath the bed to allow him to cantilever the floor out beyond the

golf cart frame. (In case you're confused about the jack ---

Bradley was upgrading the springs, which Mark will  post about later. I

just stole the photo for this post.)

post about later. I

just stole the photo for this post.)

Meanwhile, Bradley and

Mark teamed up on a smaller

front box to add yet

more hauling capacity, and Mark ensured the longevity of the untreated

plywood by giving

both boxes a coat of paint.

Mark and I are blown

away by the increased capacity of our new and improved golf cart

bed. With the walls removed, we easily hauled in all

six tanks, and then

I zipped back out for two heavy loads of firewood.

I felt like I was able

to haul three or four times as much wood as previously and I probably

could have stacked it even higher. The trick now will be holding

ourselves back so we don't strain the motor.

Wild grapes grow along the

roadsides in Capay Valley, California. Here's my favorite way of

using them: squishing them into juice.

Wild grapes grow along the

roadsides in Capay Valley, California. Here's my favorite way of

using them: squishing them into juice.

1. Wash and put the grapes

into a large ziplock bag. Seal the bag, removing as much air as

possible.

2. Squeeze the grapes with

your feet or fingers. Pop all the grapes. This is a very pleasant

sensual experience!

3. Pour the grapes pulp into a

strainer and press with the back of a spoon, catching the juice into a

bowl.

3. Pour the grapes pulp into a

strainer and press with the back of a spoon, catching the juice into a

bowl.

4. Do not heat the juice!

Heating it removes much of the delicious flavor. You can strain it

further, but I don't.

5. Refrigerate or freeze the

juice. If you allow the juice to stand at room temperature for a day or

so before refrigerating it, you will get some natural carbonation from

the yeast on the grape skins. I like this.

I get rave reviews from friends

about the freshness of this juice and I serve it at my B&B, Cache Creek Inn.

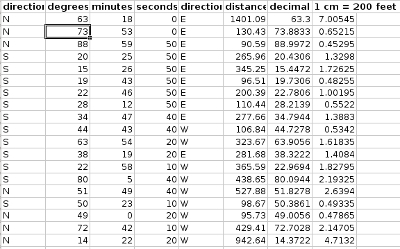

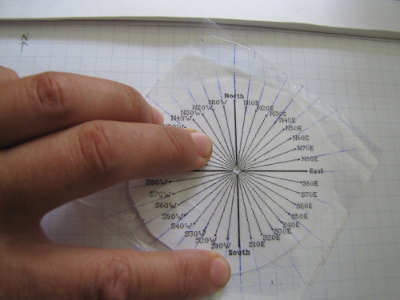

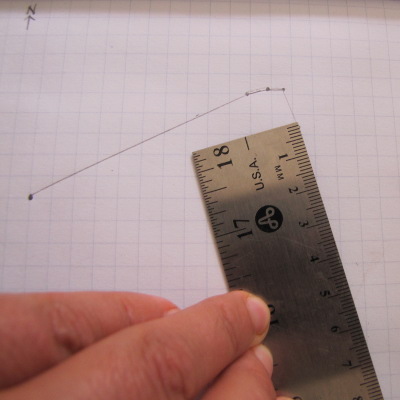

In

addition to running Cache Creek Inn, Camilla Barry and her husband

invented the visual protractor shown here, which they describe as

"the world's easiest protractor --- anyone can use it!"

In

addition to running Cache Creek Inn, Camilla Barry and her husband

invented the visual protractor shown here, which they describe as

"the world's easiest protractor --- anyone can use it!"

If you'd like to share a guest

post with our readers, check out our submission

policy. We love

learning about what other homesteaders are doing across the country and

around the world!

We got the new east porch

started last week. Our helper Bradley got about half way done with the

roof today before it got too hot.

It might be hard to see in

the picture above, but the side he's not working on is secured with a

rope so it can pivot. This allows him to get the other end screwed in

without needing an extra hand.

We've learned several

building tips like this just by observing his style and technique. It's

a nice bonus on top of the high quality craftsmanship we get to

appreciate after he goes home.

After a bit of debate,

we decided to use pallets as the floor of our new

woodshed. The  woodshed

(and half of our core homestead) is in an area with very high

groundwater, so you really can't just stack wood directly on the

ground. (Well, you can, but then the firewood is not only

unburnable, but is also impossible to pry loose from the frozen muck.)

woodshed

(and half of our core homestead) is in an area with very high

groundwater, so you really can't just stack wood directly on the

ground. (Well, you can, but then the firewood is not only

unburnable, but is also impossible to pry loose from the frozen muck.)

In our previous

incarnation, Mark cut

sassafras saplings and lay them on the ground to stack on top of, but those quickly sunk into

the mud from the weight of the firewood. My pallets may too ---

we'll just have to wait and see.

The other innovation (in

addition to size) for wood shed 2.0 is adding some two by fours to

partially close in the walls. Our efficient

wood stoves have

very small fire boxes, and short firewood has a bad tendency to fall

back on top of me when I stack it over my head. Now I can layer

the wood so that it leans against the back of the shed, which will give

the stack better stability.

The other innovation (in

addition to size) for wood shed 2.0 is adding some two by fours to

partially close in the walls. Our efficient

wood stoves have

very small fire boxes, and short firewood has a bad tendency to fall

back on top of me when I stack it over my head. Now I can layer

the wood so that it leans against the back of the shed, which will give

the stack better stability.

I'm still plugging away

at hauling in the firewood that's been sitting out in the parking area

for months, some of which was bought and some of which was cut from a

big tree that fell on the driveway. Since the parking area wood

is wetter, those logs are going in the back of the shed, then I'll

stack the leftover firewood that was in the old shed in front for early

winter burning. We've also got a few box-elders and red maples

that Bradley cut away from the back side of the barn and left to lie

until the sap dries up a bit --- those will be added to one side of the

shed once I rustle up a few more pallets.

As you can see, we've

still got a ways to go before our winter's wood will be under roof, but

it's great to make progress (and to think of cold weather on a

sweltering summer day).

Our helper Bradley brought

along someone to help him today and they both finished up the new tin

roof.

This wall gets direct morning

sun. According to the inside gauge the temperature is already 5 degrees

cooler than yesterday at the same time of day.

My experiments with

persimmons are slow, but I'm making forward progress. Two years

ago, I

planted some seeds using a method I've explained in depth in a previous

post. The soil

was poor (despite potentially having the right mychorrizae in it) and

the winter's freeze and thaw pushed many of the seeds to the surface,

where they died. I

ended up with only one seedling, and it sat there for most

of last year, then didn't leaf back out after I transplanted it into

the pasture this winter.

My experiments with

persimmons are slow, but I'm making forward progress. Two years

ago, I

planted some seeds using a method I've explained in depth in a previous

post. The soil

was poor (despite potentially having the right mychorrizae in it) and

the winter's freeze and thaw pushed many of the seeds to the surface,

where they died. I

ended up with only one seedling, and it sat there for most

of last year, then didn't leaf back out after I transplanted it into

the pasture this winter.

Last year, I gathered

a lot more seeds and tweaked my technique. Rather than

letting the seeds naturally stratify outside, I wrapped them in damp

rags and then sealed them inside a ziploc bag, with the result that

several sets of persimmon seeds spent the winter molding in our

fridge. When I pulled the bags out in late May, the contents were

disgusting, but the seeds were in much better shape than my previous

batch.

After rinsing off the

seeds, I had to choose a potting soil. Despite books' admonition

to use only forest soil, I decided that potting soil characteristics

trumped soil mychorrizae. So I potted up this year's persimmon

seeds in stump

dirt. Less

than a month after planting, seedlings started popping up.

The

first seeds to germinate were gathered from a scat last November.

I didn't think the seeds were in terribly good shape since they seemed

a bit dried out, but as many of our readers suggested, passing through

the gut of an animal definitely aids in persimmon germination.

For a week, I thought the scat seeds were the only ones that were going

to sprout, but then plants in other pots started unfurling their leaves

--- looks like I'll have a lot of persimmons to play with this year!

The

first seeds to germinate were gathered from a scat last November.

I didn't think the seeds were in terribly good shape since they seemed

a bit dried out, but as many of our readers suggested, passing through

the gut of an animal definitely aids in persimmon germination.

For a week, I thought the scat seeds were the only ones that were going

to sprout, but then plants in other pots started unfurling their leaves

--- looks like I'll have a lot of persimmons to play with this year!

Since our core homestead

is really too small for many (any?) American persimmons, my plan is to

repot these seedlings into individualized pots before they get too

big. After a year of growth, they'll be ready to have Asian

persimmon scionwood

grafted onto them, and the year after that they'll go into our chicken

pastures.

That is, if our internship

property doesn't

materialize in the next year. The spot we'd been salivating over

fell through, but we haven't let the dream die. Maybe we'll have

a big forest pasture just waiting for persimmons next spring?

The new diy

golf cart pick up bed

increased our rear load capacity from 7 buckets to 9.

We've got a few ideas on

squeezing room for more.

1. Haul buckets with sides

removed. Maybe a ratchet strap would hold them in place. Extending the

sides out just a few inches would allow an additional 3. It might

require a post at each end of the back for the ratchet strap to wrap

around.

2. Modify the sides so they

angle outward and maybe go higher up so another layer of buckets can

fit on top of the bottom layer increasing the rear load limit to 24.

That might be too much weight when hauling moist manure or gravel, but

wood chips should be light enough for that much volume.

While I've been playing

in the garden and Bradley's been building things, Mark has faced the

most difficult job on the farm --- organizing the barn.

I believe in being

honest on our blog, but sometimes you just don't need to see the worst case

scenario. So there are no before photos that go with this

post. Suffice it to say that for five years, only a small portion

of the barn was waterproof, and that area had no solid walls  on which to hang shelves and

tools. As a result, everything in the barn was piled in a mass

right in front of the doors.

on which to hang shelves and

tools. As a result, everything in the barn was piled in a mass

right in front of the doors.

A new

roof opened up

exciting barn area, but didn't do anything about the jumble of

machinery, tools, and so forth that had built up in the aisle.

For the last few weeks, Mark has been dealing with years of neglect,

which mostly consists of putting things on shelves and nails. I'd say

he's about halfway done (or maybe even more), with the result that we

can walk into the barn again!

The long term goal is to have

room to stable the golf cart and lawn mower in a nearly clear central

aisle, with the sides being split up into work and storage areas.

We may eventually build lofts too, either just for fun, for guest

quarters, or for biomass stockpiling (aka hay lofts). There's

certainly plenty of vertical area to take advantage of in this old

tobacco-drying barn.

The long term goal is to have

room to stable the golf cart and lawn mower in a nearly clear central

aisle, with the sides being split up into work and storage areas.

We may eventually build lofts too, either just for fun, for guest

quarters, or for biomass stockpiling (aka hay lofts). There's

certainly plenty of vertical area to take advantage of in this old

tobacco-drying barn.

I just thought you

should know why Mark's been quiet about his projects lately --- he's

been slaving away on an unphotogenic task that no one else wants to

tackle. Thanks, honey, for perservering!

The DeWalt impact driver is

an awesome innovation in drill technology.

We've been using ours for a

few months now. I could tell you how the torque feature lets the drill

decide when to add more power or back off by making a loud clicking

sound, but the best way to appreciate what a great tool this is would

be to look at the reviews on Amazon. 111 five star reviews with only 1

one star review from a guy who had issues with how his driver smelled.

A good example is shelf

brackets. I was putting up a new shelf in the barn recently trying to

use the old Dewalt regular drill. The wood was hard enough to cause

problems. Either it would break off the head or stop gripping and begin

to strip the screw. When I finally walked over to get the impact drill

the difference was obvious.

I was going to write a

long post about why Mark and I decided to sink this year's retirement

money into farm infrastructure (aka paying Bradley to build us things)

rather than putting cash in the bank. About how it's just another

example of the homesteading motto: keep your eyes open for

opportunities and then seize the day. We figure Bradley's obvious

skills and expanding confidence will soon put him out of our league, so

we're accepting every possible minute he can spare to make our farm

more self-sufficient until that inevitable day comes.

But I suspect you don't

really care why so much new infrastucture is coming to the farm

this summer, and would rather read about how it all happens. So

here are lessons learned from porch 2.0.

But I suspect you don't

really care why so much new infrastucture is coming to the farm

this summer, and would rather read about how it all happens. So

here are lessons learned from porch 2.0.

With porch 1.0, we had already bought four

by fours to support the roof, but Bradley was involved in the supply

run this time around and had other ideas. He explained that using

a pair of two by fours for each support post is just as sturdy as using

a four by four, and also allows you to attach the post more securely to

the floor (as you can see here), all while costing significantly

less. The only downside of this method is that you end up with a

support that's 3 inches by 3.5 inches rather than one that's 3.5 inches

by 3.5 inches, but that won't be an issue if you're not trying to put

heavy things on top.

Next, Bradley asked why we'd

buy inexpertly-cut stair risers when he could make a more stable set of

steps out of dimensional lumber. He built the simple stairs above

for the uphill side and the enticing steps to the right and below for

the downhill side.

Next, Bradley asked why we'd

buy inexpertly-cut stair risers when he could make a more stable set of

steps out of dimensional lumber. He built the simple stairs above

for the uphill side and the enticing steps to the right and below for

the downhill side.

In both cases, Bradley

cobbled the staircases together out of odds and ends we had leftover

from other projects. You can see that each step is made from

multiple boards so that we didn't have to rush to the store for wider

planks, and that the stair steps on the downhill side rest on little

pieces of lumber attached to the inside of pairs of slanted

boards. This is all treated lumber since the area gets extremely

wet in the winter.

Speaking of wet, muddy

ground, I'm starting to realize that Mark's right to put porches so

high up on our priority list. It's amazing how much effort (and

mental energy) has been drained over the years by slogging through the

mud pit that develops over the winter in the area that's now under roof

outside the East Wing. In addition to looking forward to the

winter luxury of dry feet, we've enjoyed the summer luxury of cooler

living conditions without the need for electricity during this current

heat wave.

But the most important

benefit of the porches is harder to quantify and is due to the fact

that porches make us spend a lot more leisure time outside. Stay

tuned for the startling discovery that resulted from that outdoors time, coming up in tomorrow's post.

Anna noticed some deer damage

over the weekend. The first of the year.

It was a minor incursion, but

we know from past

experience that each visit gets longer as the offending deer feels

more comfortable.

We decided to make today the

day we finish fencing in the side where we think he or she entered. 80

more feet of 5

foot high chicken wire closes up this end of the perimeter leaving

about another 70 feet towards the east end before we have the entire

garden surrounded.

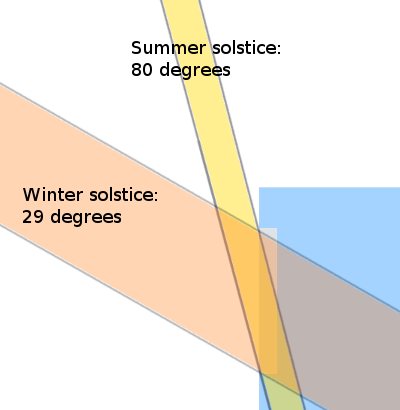

Yesterday I wrote that our

new porches tempt me and Mark to spend more time relaxing outdoors than we used to. As a

result, we've been paying more attention to the natural world, and,

after a couple of weeks, I made a shocking dicovery. The summer

sun rises in a totally different

spot than the winter sun does!

Yesterday I wrote that our

new porches tempt me and Mark to spend more time relaxing outdoors than we used to. As a

result, we've been paying more attention to the natural world, and,

after a couple of weeks, I made a shocking dicovery. The summer

sun rises in a totally different

spot than the winter sun does!

Yes, we technically

already took advantage of this fact when we planned

our south-facing trailer windows to capture winter sun without roasting

us in the summer. And if you'd asked me a year ago, I could have

told

you that the sun is lower in the sky in the winter than in the summer.

But I didn't realize

that the sun being higher in the summer sky means that it rises over

the barn instead of over the hill like it does in the winter!

This tidbit of data makes our budding passive solar heating and cooling

systems a bit more complex.

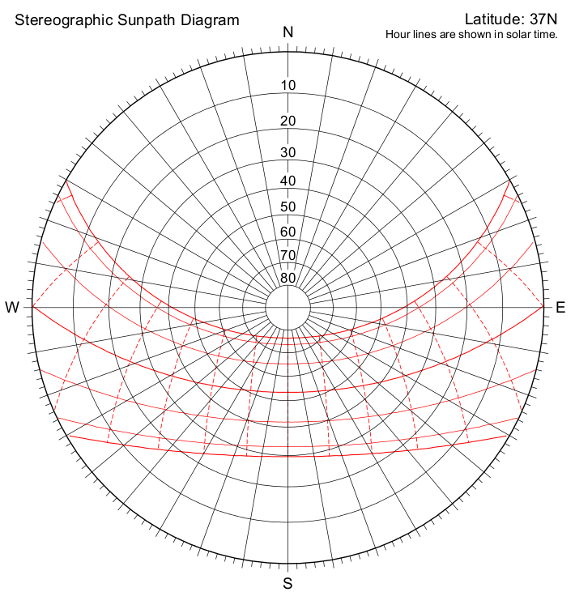

Notice how our new porch shades the East Wing from

the morning sun. I was a bit concerned that we'd be losing some

much-needed winter solar gain, but overlaying the sunpath diagram with

a map of our property shows that the sun has moved so far south in the

sky by late fall that it barely hits the side of the east wing at all.

Notice how our new porch shades the East Wing from

the morning sun. I was a bit concerned that we'd be losing some

much-needed winter solar gain, but overlaying the sunpath diagram with

a map of our property shows that the sun has moved so far south in the

sky by late fall that it barely hits the side of the east wing at all.

By the same reckoning,

we could probably block some of the scorching late afternoon sun on the

west side of our trailer without impacting winter solar heat gain as

well. I'm still  wrapping my head around the

fact that the sun doesn't rise in the east and set in the west, though,

so I think I'm going to observe a little longer before I make any

drastic decisions for that area.

wrapping my head around the

fact that the sun doesn't rise in the east and set in the west, though,

so I think I'm going to observe a little longer before I make any

drastic decisions for that area.

If you want to play with

sun patterns in your own neck of the woods, there are lots of good

resources on the web. This website allows you to

calculate the sun angle at your latitude (but you'll have to draw the

elevation mockup yourself) and this

website has downloadable sunpath diagrams, like the second image in

this post. Finally, this website allows

you to plot sunrise and sunset locations overlaying an aerial photo of

your property for any day of the year.

Or you can just build a

porch and watch the world unfold around you.

Edited to add:

Read more about passive

solar design in Trailersteading, which is now available for

$1.99 on Amazon. I hope you enjoy reading it as much as I enjoyed

writing it!

We got some much needed rain

last night and this morning.

The creek was too high for

the golf cart, which meant the poncho express if I wanted to mail

chicken waterers today.

I tried telling Lucy to take

the morning off, but she was hearing none of it and insisted on blazing

the trail to our parking area in the pouring rain.

The

mountains of produce started piling up around the first of this

month, and momentum is still building. The photos in this post

show just a few of the big harvests that have gone into our bellies

and/or freezer during the first week of July.

The

mountains of produce started piling up around the first of this

month, and momentum is still building. The photos in this post

show just a few of the big harvests that have gone into our bellies

and/or freezer during the first week of July.

(No, we didn't eat the

bug or the cats.)

Since

outdoor temperatures were in the high nineties to low hundreds for the

last two weeks, the trailer got so hot inside that Mark couldn't stand

to

spend more than about thirty seconds there. I could handle a few

more minutes, but was very glad to be able to do most of our food

processing on the porch.

Since

outdoor temperatures were in the high nineties to low hundreds for the

last two weeks, the trailer got so hot inside that Mark couldn't stand

to

spend more than about thirty seconds there. I could handle a few

more minutes, but was very glad to be able to do most of our food

processing on the porch.

In addition to cooler

temperatures, when you work outside, you get

visited by fascinating insects like the wheel bug above. These

predatory insects like to eat caterpillars and Japanese beetles, so I

was thrilled to see one carried in on the produce. (Be careful

--- I hear they have a painful bite.)

After figuring out where to process the produce, the

next decision was what to do with it. First

step --- eat as much as possible right away! At this time of

year, I try to put a cucurbit on our plate for each lunch and dinner,

along with another vegetable or two. I've also been

trying out various vegetable salad mixtures, all of which have been

very heavy on the cucumbers to use up that bountiful crop.

Despite

the joy of working on the porch, I've been giving away more food than

usual. Due to the wonders of quick

hoops, we only ate

about

twenty gallons of frozen summer produce between us during the off

season, which means I lowered my quotas on everything except vegetable

soup. (It

seems like we can eat an unlimited amount of vegetable

soup.) Although summer vegetables sound more interesting than

kale and lettuce, when the former is frozen and the latter is fresh, we

subsist nearly entirely on the latter.

Despite

the joy of working on the porch, I've been giving away more food than

usual. Due to the wonders of quick

hoops, we only ate

about

twenty gallons of frozen summer produce between us during the off

season, which means I lowered my quotas on everything except vegetable

soup. (It

seems like we can eat an unlimited amount of vegetable

soup.) Although summer vegetables sound more interesting than

kale and lettuce, when the former is frozen and the latter is fresh, we

subsist nearly entirely on the latter.

I did plant less of

certain crops in 2012 and used less manure to fertilize, but the garden

seems bound

and determined to churn out just as much food as last year despite

having a smaller area planted. As the person we see the most,

poor Bradley has been burdened with the excess. Maybe that huge

bag of summer squash and cucumbers we pawned off on him Friday is the

reason he had

other plans and couldn't come back to work on Monday?

"I left the woods for as

good a reason as I went there. Perhaps it seemed to me that I had

several more lives to live, and could not spare any more time for that

one. It is remarkable how easily and insensibly we fall into a

particular route, and make a beaten track for ourselves. I had

not lived there a week before my feet wore a path from my door to the

pondside; and though it is five or six years since I trod it, it is

still quite distinct."

"I left the woods for as

good a reason as I went there. Perhaps it seemed to me that I had

several more lives to live, and could not spare any more time for that

one. It is remarkable how easily and insensibly we fall into a

particular route, and make a beaten track for ourselves. I had

not lived there a week before my feet wore a path from my door to the

pondside; and though it is five or six years since I trod it, it is

still quite distinct."

Thoreau ends Walden by admonishing us to live

our lives fully, not to fall into ruts or societal traps. He

tells us to explore our inner world, to live fully in the moment, and

to "love your life, poor as it is."

Thoreau ends Walden by admonishing us to live

our lives fully, not to fall into ruts or societal traps. He

tells us to explore our inner world, to live fully in the moment, and

to "love your life, poor as it is."

How's that for an upbeat

ending to a quotable but laborious book?

I'd love to hear from

everyone who read part or all of Walden, now that the first book

club read is at its end. What were your overall thoughts?

Did you think Thoreau was a long-winded poser, or a mystic

visionary? Did the book inspire you; if so, to do what?

Personally, I'm ready to move

on from Thoreau and crack open The

Dirty Life, which we'll begin discussing on July 25. For my

college buddies: the husband in The Dirty Life's team is a

graduate of our alma mater, if that's an inducement to join the next

discussion.

Personally, I'm ready to move

on from Thoreau and crack open The

Dirty Life, which we'll begin discussing on July 25. For my

college buddies: the husband in The Dirty Life's team is a

graduate of our alma mater, if that's an inducement to join the next

discussion.

As we wait for everyone's

copies of the next book to arrive on interlibrary loan, feel free to

read back over my posts (and reader comments) on Walden's

chapter

1, chapter

2, chapters

3 and 4, chapters

5 and 6, chapters

7 and 8, chapters

9 and 10, chapters

11 and 12, chapters

13 and

14, and chapters

15 and 16. Several of us are subscribed to the comments and

will see contributions you post there, even if they're out of sync.

This ultra cute Gray Treefrog showed up today for a

visit.

I looked around the sink area

and found a gap I forgot about when we brought our gray water line into

the trailer after burying

it last year.

Is there a connection between

Gray Treefrogs and gray water?

I don't think so.

Good afternoon, sweet Anna!

Good afternoon, sweet Anna!I've recently been mulling over the costs of homesteading (or whatever else people choose to call it) and thought it would be wise to ask you what you think.

Purchasing land and home aside, what are the the bank account costs of establishing a garden that can feed two people with the methods that you use? Even if you buy the land outright and the home is free, or also bought outright, there are still repairs that will have to be made over time, is there a way to guess a general amount per year for that? How much to maintain soil, gardening equipment? Seed preservation, food storage, and livestock if one keeps the smaller, more cost-effective animals?

You guys have been making great strides on the farm improvements by utilizing your helpful assistant lately, what do those sorts of costs look like? Obviously much of what you can explain are only guesses or your own costs, but what are some good methods for keeping track of costs once we begin on our own journey on the land?

I suppose what I'm asking is:

how much does it cost to maintain and how much does it cost to improve

over time? I think that some of us who are hoping to go back to

the land would like to know how much to plan for. We need to

know, generally of course, how to determine the money we would need to

tuck away, invest, or what level of income to maintain so that our

lives can function while we find our balance, then how much it will

take to cruise right along.

I suppose what I'm asking is:

how much does it cost to maintain and how much does it cost to improve

over time? I think that some of us who are hoping to go back to

the land would like to know how much to plan for. We need to

know, generally of course, how to determine the money we would need to

tuck away, invest, or what level of income to maintain so that our

lives can function while we find our balance, then how much it will

take to cruise right along.Most people --- okay, maybe just me --- don't have any idea how to plan for food. I don't know how much salad I eat, if I'll need potatoes, if I can really stomach that much zucchini, etc. And worse, I'm worried that even if I calculate enough, that what I grow won't make it. Every year is an experiment, surely, but how can you figure in the cost of having to go to the store anyway because of crop failure, etc?

Is this all just too BIG a question? Is it simply too much to answer? I don't know who else I can ask.

Thank you so much for all you do,

Brandy

I've been receiving a lot of

thought-provoking reader questions like this via email lately, but

there are always so many other things to post about that I never seem

to get around to answering them. There's no time like the present

to start, though, and I thought Brandy's question might be something

that other readers would like to chime in on. (Plus, with a

salutation like that, how could I not make this the first reader

question post of the summer?)

I've been receiving a lot of

thought-provoking reader questions like this via email lately, but

there are always so many other things to post about that I never seem

to get around to answering them. There's no time like the present

to start, though, and I thought Brandy's question might be something

that other readers would like to chime in on. (Plus, with a

salutation like that, how could I not make this the first reader

question post of the summer?)

While I think we should

all talk about money more, this is a tough question to answer because

everyone will spend a different amount of cash on their

homestead. Mark and I believe strongly in paying as we go, which

means that in the early years on the homestead, we spent next to

nothing on the garden and improvements. Our combined annual

income was $12,000 at the time, so we simply couldn't afford any excess.

That said, I had been saving

ever since high school, so I had enough of a nest egg to pay some hefty

startup fees. It cost $1,266 for our electric hookup and we paid

another $2,000 to move our free

trailer onto the land. Mark and I were just barely dating at

the time, so I paid off his debts in exchange for labor before we

pooled our incomes and started going steady. As a result, we went

into the endeavor debt-free, except for a no-interest,

pay-when-you-feel-like-it loan from a very good friend to buy the land.

That said, I had been saving

ever since high school, so I had enough of a nest egg to pay some hefty

startup fees. It cost $1,266 for our electric hookup and we paid

another $2,000 to move our free

trailer onto the land. Mark and I were just barely dating at

the time, so I paid off his debts in exchange for labor before we

pooled our incomes and started going steady. As a result, we went

into the endeavor debt-free, except for a no-interest,

pay-when-you-feel-like-it loan from a very good friend to buy the land.

During our first two

years on the farm, I budgeted $100 for seeds each year, and if I could

drum up the cash, spent another $50 or so on perennials, but we didn't

add any other storebought inputs. Many of our first perennials

were gifts from friends --- our family's heirloom Egyptian onions have

now spread across the U.S., and a friend's gift of two varieties of

strawberry plants have fed us bushels of berries while also allowing me

to give away starts to my family and friends. We started

our grapes by taking hardwood cuttings from a friend's orchard, and

our huge ever-bearing raspberry patch started as a single plant that

came as a freebie with our order of fruit trees. The theme here

is that if you understand how to propagate plants and save seeds (and

are patient), you can get the plant side of your farm going with very

little cash.

Our first chickens were a

partnership with a neighbor who wanted fresh eggs but didn't want to

put the time into building chicken tractors and taking care of the

livestock. He paid for the birds and we only had to buy chicken

feed, giving him some eggs in the early years. That said, chicken

feed isn't cheap, so poultry care made up a large proportion of our

early farm costs ($262 in 2008, before we gave away some of the 20

birds we started with).

Our first chickens were a

partnership with a neighbor who wanted fresh eggs but didn't want to

put the time into building chicken tractors and taking care of the

livestock. He paid for the birds and we only had to buy chicken

feed, giving him some eggs in the early years. That said, chicken

feed isn't cheap, so poultry care made up a large proportion of our

early farm costs ($262 in 2008, before we gave away some of the 20

birds we started with).

Meanwhile, we turned the

trailer from a windowless, throwaway item into a living space using

free building materials my mother found on the curb on trash day and

that we picked up at a giveaway of a service organization that builds

houses. We did splurge a hundred dollars or so to get new

double-glazed windows, which had been custom-made but not picked up, so

were vastly reduced in price. Tools were the  expensive

part, but my father found a lot of hand tools for me at an auction and

Mark's mother gifted us with many power tools. (The December

volume of Weekend Homesteader covers the tools that I consider the

bare essentials for homesteading.)

expensive

part, but my father found a lot of hand tools for me at an auction and

Mark's mother gifted us with many power tools. (The December

volume of Weekend Homesteader covers the tools that I consider the

bare essentials for homesteading.)

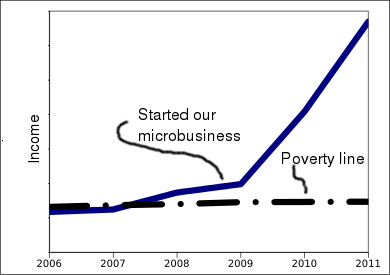

While this sounds like

hard-scrabble living (and it was in certain ways), we also had the

freedom to invest our time in breaking free of the rat race and

figuring out where our passions lay. Since we weren't saddled

with debt, we were able to tighten our belts and start our microbusiness, finally rising above the

poverty line. More recently, income from my writing has added to

the coffers, which means we suddenly have plenty of extra cash to throw

at homesteading projects.

As

our income has increased, we've put more and more money into the

farm. We spent nearly $900 on each of our efficient

wood stoves (getting

some of that back in taxes), which lowered our heating bill and finally

allowed me to stop wearing a winter coat inside. The

East Wing cost us another $1,100, and more recently we spent

$4,000 on the barn roof and have paid Bradley around $3,000 this summer

for lots of projects (only some of which you've seen on the blog) along

with perhaps that much again for his building supplies.

As

our income has increased, we've put more and more money into the

farm. We spent nearly $900 on each of our efficient

wood stoves (getting

some of that back in taxes), which lowered our heating bill and finally

allowed me to stop wearing a winter coat inside. The

East Wing cost us another $1,100, and more recently we spent

$4,000 on the barn roof and have paid Bradley around $3,000 this summer

for lots of projects (only some of which you've seen on the blog) along

with perhaps that much again for his building supplies.

Lately, we've been

investing lots of cash in straw and cover crop seeds --- Mark talked me

into splurging $80 this summer on 20 pounds of oilseed radishes to

really boost the farm's fertility and we've also spent $650 in the last

year on straw. And, as you've probably noticed, we've been

devoting more cash to perennials that are experimental, half of which

fail to thrive in our climate, but others of which have found a niche

on our farm.

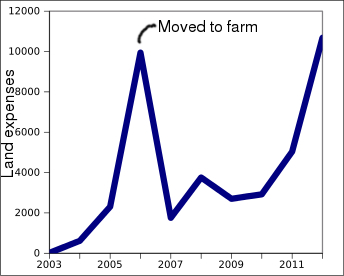

I keep track whenever money

goes in or out of our pockets using the free program GnuCash. It

reports that we've spent just shy of $40,000 on the farm since 2003,

which you should take with a grain of salt --- I'm not as careful to

make sure that everything is categorized correctly in our non-business

accounting. But you can get an idea for annual costs, ranging

from that expensive startup year, through the years when we were barely

getting by, and finally to our push in the last year to invest in our

homestead.

I keep track whenever money

goes in or out of our pockets using the free program GnuCash. It

reports that we've spent just shy of $40,000 on the farm since 2003,

which you should take with a grain of salt --- I'm not as careful to

make sure that everything is categorized correctly in our non-business

accounting. But you can get an idea for annual costs, ranging

from that expensive startup year, through the years when we were barely

getting by, and finally to our push in the last year to invest in our

homestead.

So, the take-home

message is --- assuming you don't go into debt to get started, your

annual costs could be as low as $2,000 to $3,000 per year to run a two

person homestead. However, that assumes you're willing to do

without and pinch pennies (much easier if you start with nothing and

slowly build up your infrastructure than if you move from a fancy place

in the city and are shocked to live without running water for the first

few years).

The

one ongoing expense you can't get away from is property taxes, which

is why I highly recommend buying cheap land and living below your

means. We purchased subpar swamp and hillside in a

poverty-stricken region of Appalachia for $600 per acre, and even

though property taxes have risen considerably in the last eight years,

we only paid $321 in county taxes in 2011.

The

one ongoing expense you can't get away from is property taxes, which

is why I highly recommend buying cheap land and living below your

means. We purchased subpar swamp and hillside in a

poverty-stricken region of Appalachia for $600 per acre, and even

though property taxes have risen considerably in the last eight years,

we only paid $321 in county taxes in 2011.

I hope that helps you

get a handle on the financial side of homesteading. I didn't

cover all of your questions in depth since it's hard to put

a cash price on the value of the produce we grow (although I did mean to add

that I think any reasonably interested person can grow all of their own

vegetables as long as they diversify enough that if one crop fails,

they can eat something else). Maybe others will chime in with

their answers to Brandy's question?

(By the way, all of

these photos are from when Mark and I were courting, before we moved to

the farm. And, as a postscript to the many people who have

emailed questions I haven't yet answered --- don't worry, you're still

on my list!)

I've been having second

thoughts on the tri-bladed

metal brush knife also known as the "Ninja Blade".

It cuts heavy grass and light

scrub, but every now and then I would hit a small tree or the ground of

a hillside that would stop it cold.

The FS90-R

recovers nicely, but can only handle a limited number of cold stops

like that before the flywheel shaft key sheers.

About an hour of research on

a weedeater forum revealed some bad news. Turns out you can't just

replace the flywheel shaft key. The key is built into the flywheel,

which would cost 65 dollars if you could order one, which you cannot

unless you're an official Stihl

dealer.

Ours is still under

warranty, but it's been in the shop for a month, and when I called them last week I got

the impression from the guy I talked to that their technician is either

slow or buried or both.

Even though winter feels very

far away, the dog days are the right time to start

your fall garden.

Last year, I

had a lot of trouble getting seeds to germinate in the hot, dry weather, so this year I opted to

start broccoli, cabbage, and (a new experiment this year) brussels

sprouts inside.

Even though winter feels very

far away, the dog days are the right time to start

your fall garden.

Last year, I

had a lot of trouble getting seeds to germinate in the hot, dry weather, so this year I opted to

start broccoli, cabbage, and (a new experiment this year) brussels

sprouts inside.

Sure enough, it was so

hot that I couldn't even get the first set of seeds to germinate inside

the trailer. So I moved the flats to the porch and refilled them

with stump

dirt from my favorite tree (the output of which I save for special

occasions). The result was cute little seedlings popping up

within a few days.

If I'd only known that

our weather was going to have a mood swing, I could have

direct-seeded. Recently, I've learned that summer weather (at

least in our neck of the woods) tends to get stuck in feedback loops,

which explains why some summers are distressingly cool and wet while

others are just as distressingly hot and dry.

A couple of weeks ago, I

noticed a several degree difference in temperature (as measured by my

bare feet) between the lush clover growing where our sink graywater

spills out and the parched clover just fifteen feet away. My feet

were picking up on the same factor that influences our summer weather

--- dry soil makes the air hotter while wet soil makes the air

cooler. Maybe that's why once the rains finally came, they kept

on coming all week long?

I don't mind a few more days

of rain if it means the fall garden will get off to a good start.

Carrot seedlings (planted at the beginning of July) are already up and

I can just feel the snap pea seeds I set out Thursday plumping up in

the wet earth. Once those sprout, I've put in an order for more

hot, dry weather to keep the tomatoes and cucurbits happy.

I don't mind a few more days

of rain if it means the fall garden will get off to a good start.

Carrot seedlings (planted at the beginning of July) are already up and

I can just feel the snap pea seeds I set out Thursday plumping up in

the wet earth. Once those sprout, I've put in an order for more

hot, dry weather to keep the tomatoes and cucurbits happy.

In the meantime, the

photo above shows what I look like when I squelch in from the

garden. Can you tell I'm soaked from mid-thigh down and filthy

from head to toe? Pure bliss....

This is me switching from

boots to "going to town" shoes.

Its been raining for over a

week, but today was the first day it felt wet enough to pull out the Mucks.

Many people believe that if

you break a mirror you get seven years of bad luck. The only

mirror I own is at the entrance to the chicken coop (a reused closet

door), so I can't speak to the truth of the mirror legend. But I

can tell you that if you let weeds go to seed in your garden, you're in

for seven years of extra work.

Many people believe that if

you break a mirror you get seven years of bad luck. The only

mirror I own is at the entrance to the chicken coop (a reused closet

door), so I can't speak to the truth of the mirror legend. But I

can tell you that if you let weeds go to seed in your garden, you're in

for seven years of extra work.

Even though we

reclaimed the forest garden from the weeds last summer, we'll be putting in extra

effort for the next few years to ensure that the offspring of those

weeds don't regain a foothold. I've got three weapons in my

anti-weed arsenal at the moment --- kill mulches, tomatoes, and

butternuts.

Kill mulches are the

obvious solution. I rip out as many of the weeds as I can, then

top what's left off with a heavy layer of cardboard and then wood chips

(around the trees) or straw (around the vegetables). I've found

that in areas with vigorous vines, like Japanese honeysuckle, it may

take multiple kill mulches a few months apart to really wipe out the

invaders.

Next, I plant tomatoes

next-door to the trouble zones. Mark and I love tomatoes more

than any other plant in the summer garden, and they're a bit of a

struggle in our humid climate. So I commit to pruning off

diseased leaves and new suckers every week, then tying the tomatoes up

to their stakes. The result is that I pay attention to that part

of the garden on a regular basis, and no weed goes to seed without me

noticing.

The final solution in my

anti-weed campaign this year is butternut squash. Although we

love butternuts, I consider them plant-it-and-forget-it crops.

But as long as the weed pressure is relatively low, they do a pretty

good job of acting as a living mulch, shading the ground so seeds don't

germinate.

So far, I'm very pleased

with the results --- for the first time since we moved to the property,

the forest garden is starting to look like a productive and happy

place. Maybe it won't take a full seven years to outrun our bad

luck after all.

When I first started

homesteading I was using one pair of decent work boots as an all season

solution.

It wasn't working all that

well in our Rainforest like climate. My last all purpose boot was an

expensive pair of Timberlands, which only lasted 10 months before they got worn to the point of no

repair.

My new strategy is to split

the work into three chunks.

1. Dry to moist- Ariat hiking boots

2. Soaked in the ground wet- Muck Chore boots

3. Flooded over the calf- Pro Line hip waders

None of these options are

steel toed. Something I was forced to wear in the Navy where dropping

something heavy was an everyday possibility. I guess if I was doing more

industrial farming or working with a tractor I might consider going

back to wearing a steel toe.

Soon after nadiring

the Warre hive the

second time, I saw a

huge mass of bees in the air above their home. This was during

the sweltering weather we faced at the end of June, and I thought for a

few minutes that the hive might be overheating and the bees

absconding. However, it turned out that all the fuss was merely a

huge brood of new workers taking their bearings before getting to work.

Despite all of the extra

hands to make light work, two weeks later, the colony still hasn't

moved down into the fourth box. I suspect the slowdown is mostly

due to a week of rain --- bees don't do well flying between raindrops,

so they're stuck at home eating through their winter stores.

Despite all of the extra

hands to make light work, two weeks later, the colony still hasn't

moved down into the fourth box. I suspect the slowdown is mostly

due to a week of rain --- bees don't do well flying between raindrops,

so they're stuck at home eating through their winter stores.

When the clouds cleared

Saturday, I saw bees all over, but was surprised to notice that the

busiest spot seemed to be our patch of blooming sweet corn. Corn

is supposed to be wind-pollinated, but from the bumblebees, sweatbees,

and honeybees buzzing around the flowers, I have to conclude that

insects do a bit of work there as well.

Hopefully we'll get

enough of a break from the rain that the bees can visit the buckwheat

and clover, too, and fill up on nectar to help them drawn out the

foundationless frames. They've still got a lot of work to do so

that I don't have to embark on fall feeding to top up their winter

honey.

I was tinkering around with a

new type of deer

deterrent today.

The motion detector Sensor Plug in the bottom right

hand corner should turn the oscillating fan on if a deer tries to come in through

our main entrance. The movement from the flagging tape and the noise

from the banging golf balls should make a deer run back into the woods.

There's an adjustment on how

long the fan will go before resetting, and a red light on the front

indicates when there's movement. Stay tuned to see how this contraption

stands up through my series of tests.

Although the title of

this post may seem like an odd question to ask, it makes sense once you

start thinking about worm bins. After all, your goal when adding

biomass to a compost bin is similar to your efforts when making a

compost pile, and a well-made compost pile quickly heats up from

microbial action. So, can worms stand hot composting?

The reason I started

researching this question is because the manure we used to fill our second

worm bin was fresher than I thought and soon heated up. I

didn't think to stick in the compost

thermometer until this weekend, but suspect the manure got hotter

than the 90 degrees at which compost worms perish.

The reason I started

researching this question is because the manure we used to fill our second

worm bin was fresher than I thought and soon heated up. I

didn't think to stick in the compost

thermometer until this weekend, but suspect the manure got hotter

than the 90 degrees at which compost worms perish.

In heartening news, I

tossed similarly fresh manure on top of the worms in the first worm bin

a week earlier, and I just noticed that those worms have moved to the

surface and started to work. I suspect the worms were able to

hide at the extremities of the bin, where temperatures were lower, then

slither back into the center once the first burst of heat subsided.

I hope that the soaked

newspaper I added to the second bin gave those worms a similar escape

hatch. (Adding carbon slows down a compost pile, which lowers the

heat.) Only time will tell whether we have to seed the second bin

again, but I know that after this, I'll be careful to let manure cool

down before adding compost worms.

I hope that the soaked

newspaper I added to the second bin gave those worms a similar escape

hatch. (Adding carbon slows down a compost pile, which lowers the

heat.) Only time will tell whether we have to seed the second bin