archives for 06/2012

I love using

stump dirt as potting soil, and last year I concluded

that this

miraculous substance was probably mushroom compost. Now I'm going to

guess again --- maybe beetle castings?

Three weeks after Mark cut

down a very

decayed stump, I

started piling the debris in my wheelbarrow to move to a new hugelkultur mound. Imagine my surprise

to find the rotting wood literally wiggling with life!

Three weeks after Mark cut

down a very

decayed stump, I

started piling the debris in my wheelbarrow to move to a new hugelkultur mound. Imagine my surprise

to find the rotting wood literally wiggling with life!

The most obvious living

things in the stump were these impressive beetles. At least half

a dozen were present, which is typical of the Horned Passalus (Odontotaenius

disjunctus) since

the species is subsocial, with several adults sharing the duties of

childcare.

The Horned Passalus eats

"decaying wood and/or fungi" (according to Bugguide.net), and  I realized that the round

pellets that make up stump dirt do look a lot like castings (aka

poop). I wonder if beetle castings have the same near-mythical

properties as worm

castings?

I realized that the round

pellets that make up stump dirt do look a lot like castings (aka

poop). I wonder if beetle castings have the same near-mythical

properties as worm

castings?

Of course, it's not

really fair to assume the beetles are entirely responsible for creating

stump dirt. The log was also home to wolf spiders, slugs, sow

bugs, wood cockroaches (hiding in galleries in the less decomposed

wood), tiny snails, and much smaller inhabitants that I could barely

make out with the naked eye. So the jury's still out on who or

what produces stump dirt.

It's funny how an open space

makes you think of possibilities.

Anna's first idea when she

saw our new

barn floor was how it would make a nice dance area. For me I saw

enough elbow room for a pool table.

I'm not good at taking

Mondays off, so we worked on Memorial Day. But a rainy

Friday? Sounds like perfect weather for virtual

homesteading.

The porch continues to be one of the

best investments we've made since moving to the farm. On a hot

afternoon, surveying my domain from the porch makes me feel like I'm on

a cruise. And playing a board game with my brother while the rain

pounds on the metal roof reminds me of several happy childhood (and

young adult) experiences all rolled into one.

Just a couple of years ago,

though, I don't think I would have enjoyed the porch so much.

We've been making an effort lately to spend a bit of energy and money

deleting stressors around the farm, and the attention is really paying

off. First was the barn

roof project, then

Mark took the ninja

blade to the

sinkhole, and last week our helper and his stepson cleaned up the rest

of the gully. Mark's fences around

our perimeter also remind me that nothing beyond the fenceline is my

problem.

Just a couple of years ago,

though, I don't think I would have enjoyed the porch so much.

We've been making an effort lately to spend a bit of energy and money

deleting stressors around the farm, and the attention is really paying

off. First was the barn

roof project, then

Mark took the ninja

blade to the

sinkhole, and last week our helper and his stepson cleaned up the rest

of the gully. Mark's fences around

our perimeter also remind me that nothing beyond the fenceline is my

problem.

Now when I look out the

window or off the porch, all I see is beauty and I can relax. I'm

glad Mark has mitigated my idealism enough that I can (mostly) quash my

guilt at hiring in a bit of help and simply enjoy the results.

The new DeWalt hammer drill has a

surprising amount of power.

Switch it to hammer mode and

you'll get a pounding action that makes short work of concrete and

other masonry material.

What I like better than the

extra power is the addition of a handy work light just above the

trigger. Why has it taken so long to come up with this obvious

improvement?

Every garden year is a

little different, which keeps me from getting bored. For example,

during the last few springs and summers, I've been madly picking asparagus

beetles, but  I've only seen a single

asparagus nibbler in 2012. I squashed it, looked ferociously for

more, then shrugged and moved on to other tasks.

I've only seen a single

asparagus nibbler in 2012. I squashed it, looked ferociously for

more, then shrugged and moved on to other tasks.

On the other hand, I

usually plant seeds for the summer garden and forget about them for a

few weeks until they're ready to be weeded and mulched. Not this

year. Something or other is happily eating my seedlings as soon

as they come out of the ground, not snipping the stems at the base the

way cutworms do, but nibbling off the cotyledons so that sad little

sticks are left behind with no energy with which to grow. Despite

three seedings, I have a total of two cucumber plants in the garden ---

I guess we won't be awash in crisp cucumbers this year. Other

summer vegetables have also been affected, although less

markedly. Luckily, the unidentified nibbler seems to have gotten

sated at last --- my most recent succession

plantings are doing much better.

Meanwhile, a hot spring has

caused problems with early crops. I try to get my broccoli into

our bellies and freezer before the cabbage worms hatch, but that wasn't

possible this year. So I'm picking green caterpillars out of the

broccoli heads (the latter of which are smaller than usual) and hoping

Mark won't notice the missed insects that end up on his plate.

(Note to spouses of gardeners: it's very endearing to find a bug on

your plate and shrug it off as "extra protein".)

Meanwhile, a hot spring has

caused problems with early crops. I try to get my broccoli into

our bellies and freezer before the cabbage worms hatch, but that wasn't

possible this year. So I'm picking green caterpillars out of the

broccoli heads (the latter of which are smaller than usual) and hoping

Mark won't notice the missed insects that end up on his plate.

(Note to spouses of gardeners: it's very endearing to find a bug on

your plate and shrug it off as "extra protein".)

But the hot spring has a

silver lining. Mark and I enjoyed a bowlful of black raspberries

Friday, a treat we usually don't partake of until the end of

June. We're gorging on sugar snap peas, crunching up baby carrots

I thin out of the vibrant carrot

bed, and watching onions plump up for later harvest. And, of

course, the tomato plants are growing like gangbusters --- one currant

tomato is already the size of a pea. Maybe this will be the year

we eat our first tomato in June?

But the hot spring has a

silver lining. Mark and I enjoyed a bowlful of black raspberries

Friday, a treat we usually don't partake of until the end of

June. We're gorging on sugar snap peas, crunching up baby carrots

I thin out of the vibrant carrot

bed, and watching onions plump up for later harvest. And, of

course, the tomato plants are growing like gangbusters --- one currant

tomato is already the size of a pea. Maybe this will be the year

we eat our first tomato in June?

I've decided that the

trick to a successful garden is to plant such a wide variety of

vegetables that no single failure will leave you hungry. That,

plus learning to shrug off problems and to learn from your mistakes,

turns every year into a good garden year.

The battery

powered deer deterrent started slowing down yesterday, which

prompted us to tinker with the idea of charging the battery with a

solar cell.

If you take apart one of

those solar powered garden lights you'll most likely find a AA battery

with a circuit board.

I'm guessing the electronic

parts prevent the battery from being over charged. I know the amps are

different on a D cell compared to AA, but I thought it was worth a try due to the fact that both batteries put out the same 1.5 volts.

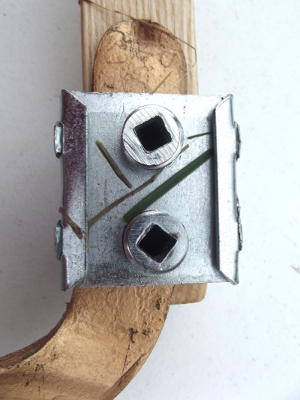

The modification was simple. Just pull out the metal battery connectors

with pliers, strip the ends and thread each one through the hole where

the screw usually fits. Snip off the plastic portion where the screw

bites into and then you'll be able to put it back together with just

one screw and the other two deleted.

The other end of the wires get hooked up to the D cell battery.

Drilling a 3/4 inch hole at an angle allows for easy mounting of the

unit while optimizing the solar angle a bit better than just having it

point straight up. I'm thinking the LED light that comes on at night might need to be bypassed to save more juice for deer deterring.

From the number of times

I've posted about them, you'd think that potato onions are a mainstay

of our diet. To follow our adventures from the beginning, read

the posts in this order:

- Potato onions (October 2009)

- Different

kinds of perennial onions (December 2009)

- Potato onion cultivation (June 2010)

- When

to plant potato onions (September 2010)

- Potato

onion bulb size (January 2011)

- Potato

onion failure (June 2011)

- Growing

bigger potato onions (September 2011)

As you can tell if you

follow all those links, potato onions were a cool idea that didn't really pan

out...until now!

The new variety we planted

last fall --- Yellow Potato Onions from Southern Exposure Seed Exchange

--- are acting more like the books say they should. About a

quarter of the plants simply made one big bulb, and the other 75% have

divided into clusters of four to ten smaller bulbs. Most

important, every bulb looks big enough to be worth peeling, even the

smallest ones.

The new variety we planted

last fall --- Yellow Potato Onions from Southern Exposure Seed Exchange

--- are acting more like the books say they should. About a

quarter of the plants simply made one big bulb, and the other 75% have

divided into clusters of four to ten smaller bulbs. Most

important, every bulb looks big enough to be worth peeling, even the

smallest ones.

The great thing about

perennial vegetables is that once you figure them out, they're much

easier to grow than annuals. Take our garlic, for example ---

we'll be pulling

the heads out of the ground this week, curing

them, then planting

the biggest cloves in the fall. That's the sum total

of the garlic workload for the year (except for occasional weeding and

mulching, of course). I want onions to be that simple!

So we won't eat a single

potato onion in 2012. They'll all go back in the ground, where

the big bulbs will (hopefully) turn into lots of smaller bulbs and the

small bulbs will (hopefully) turn into one or a few big bulbs.

Maybe next year (or the year after) there will be enough to eat and I

can stop fiddling with transplanting tiny onion seedlings in the early

spring.

There are three free book

opportunities today, so be sure to skim all the way through this post,

even if it's boring.

There are three free book

opportunities today, so be sure to skim all the way through this post,

even if it's boring.

I never heard from

Jason, the winner of last week's free book, so I'm moving on down the

list.

Yesterday's

experiment to power the mechanical deer deterrent with a small

outdoor solar light only helped a little.

I measured an increase in

voltage from 1.21 in the morning to 1.36 just before dinner.

Roland made a good point in

the comment section concerning the danger in charging Alkaline

batteries. The new plan is to try some rechargeable AA batteries we've

got laying around. Eric in Japan suggested two in a parallel circuit

and I think that's the direction I'll start out with.

If your garlic looks like the

photos above, harvest it last week!

If your garlic looks like the

photos above, harvest it last week!

Don't have a time

machine? Right now will work.

Strange leaves poking

out of the garlic plant's stalk are a sign that the cloves have already

broken through their outer wrapping and sprouted, so the garlic won't

store as well as you would have liked.

This year, the garlic

harvest snuck up on

me. Usually, we don't dig our garlic until mid to late June, but

a mild winter and hot spring matured the heads early.

Only

the softneck varieties were precocious, though. That's what

really kept me from digging a test bulb two weeks ago when the garlic

leaves started to look ratty. We hadn't seen any garlic

scapes, so no way

the garlic could be ready, right?

Only

the softneck varieties were precocious, though. That's what

really kept me from digging a test bulb two weeks ago when the garlic

leaves started to look ratty. We hadn't seen any garlic

scapes, so no way

the garlic could be ready, right?

Wrong. Even though

Music (hardneck) and Silverwhite Silverskin (softneck) usually mature

at the same time in our garden, clearly the two varieties handle early

springs differently. So about a third of our softneck bulbs are

going to have to be eaten soon after curing, rather than saved for the

winter.

Since I know someone's

going to ask this in a comment --- yes, you can just leave the garlic

in the ground to resprout and grow as a no-work perennial, but I don't

recommend it. If you don't split the cloves apart before

replanting them, a dozen little plants will be  competing with each other in

the same spot and you won't get a good yield next year.

competing with each other in

the same spot and you won't get a good yield next year.

Plus, you can't just go

out in the garden throughout the year and dig a head whenever you want

it. That spicy garlic flavor matures as the bulbs cure over the course of a month

or so out of the ground.

Stay tuned for a later

post about how well our new garlic

curing racks worked!

24 inch Pittsburgh pry bar: $4.99

Bostitch AnitiVibe hammer: $23.49

Bag of flywheel shaft

keys: $6.99

Knowing I can do this

operation in the future instead of packing the mower to a local

mechanic: Priceless!

My oldest brother (not

the one you've met here on the blog) is getting married in August, and

he asked for a family geneology as a wedding gift. So I've been

engrossed in old photos and history for the last few weekends.

I'm struck by how

everything is just a story with no clear line between fact and

fiction. Here's a typical tale from my father:

My

great Uncle George, Grandad's brother,

was a noted storyteller, and, some would say, liar. He told me once

about visiting Grandmother Hess's relatives down at the Kentucky

border, the patriarch of whom was Devil Anse Hatfield. I haven't a

clue if what he said was true or not. He told of seeing sun

glinting from rifle barrels as he traveled up the hollow to the

homestead.

My

great Uncle George, Grandad's brother,

was a noted storyteller, and, some would say, liar. He told me once

about visiting Grandmother Hess's relatives down at the Kentucky

border, the patriarch of whom was Devil Anse Hatfield. I haven't a

clue if what he said was true or not. He told of seeing sun

glinting from rifle barrels as he traveled up the hollow to the

homestead.I always took Uncle George's stories with a big grain of salt. He said the Hatfields planted their potatoes in a row going straight up the hill. It was so steep that to harvest them they just dug at the bottom and held a basket when they came pouring out.

But George showed me bear tracks on the riverbank near where he had his garden and showed me how to bake corn in the husk in fire coals. And he told about visiting Devil Anse in front of Grandmother and she didn't deny it.

Daddy also told me about

my great, great grandfather, Hector Horatio Hess, pictured in the first

photo in this post. Hector Horatio was a butcher, baker, and candle-stick-maker...I mean lawyer and

restaraunteer. He was reputed to be able to write two different

letters at the same time, one with each hand, from dictation.

Are these larger than life

characters actually real? Perhaps because my

grandfather on the other side was an engineer, my forays

into geneology are giving me an uncontrollable urge to go measure

something.

Are these larger than life

characters actually real? Perhaps because my

grandfather on the other side was an engineer, my forays

into geneology are giving me an uncontrollable urge to go measure

something.

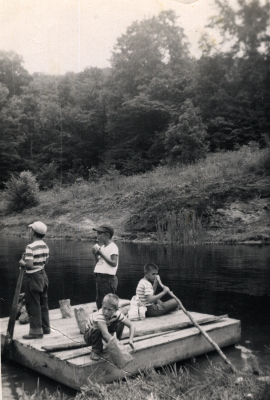

(For family members and

anyone else interested, here are the photo credits: Hector

Horatio Hess is the one in the apron, pictured in front of his

restaurant. The second photo is Daddy as a child with some

friends --- he's the one with the pole. The third photo is my

great grandfather John Hess (the driver on the right). The last

photo is Daddy, Aunt Joyce, and Aunt Jackie in their Easter clothes.)

In the most relevant section

of this week's Walden passage, Thoreau is caught out in the rain and

takes shelter in what he thought was an uninhabited hut. However,

since he had last been there, "an Irishman, his wife, and several

children" had moved in. Rather than thanking them for their

hospitality for letting him come in out of the rain, Thoreau proceeded

to lecture them about simple living.

In the most relevant section

of this week's Walden passage, Thoreau is caught out in the rain and

takes shelter in what he thought was an uninhabited hut. However,

since he had last been there, "an Irishman, his wife, and several

children" had moved in. Rather than thanking them for their

hospitality for letting him come in out of the rain, Thoreau proceeded

to lecture them about simple living.

I've excerpted the most

relevant portions below (adding in my own line breaks because Thoreau

doesn't believe in short sentences or paragraphs, but I do):

"...That I did not use tea, nor coffee, nor butter, nor milk, nor fresh meat, and so did not have to work to get them; again, as I did not work hard, I did not have to eat hard, and it cost me but a trifle for my food; but as he began with tea, and coffee, and butter, and milk, and beef, he had to work hard to pay for them, and when he had worked hard he had to eat hard again to repair the waste of his system...."

"I told him, that as he worked so hard at bogging, he required thick boots and stout clothing, which yet were soon soiled and worn out, but I wore light shoes and thin clothing, which cost not half so much, though he might think that I was dressed like a gentleman (which, however, was not the case), and in an hour or two, without labor, but as recreation, I could, if I wished, catch as many fish as I should want for two days, or earn enough money to support me for a week.

"If he and his family would live simply, they might all go a-huckleberrying in the summer for their amusement."

I believe that this passage

strikes to the heart of the problem with the voluntary simplicity

movement. The man whom Thoreau was lecturing had immigrated from

Ireland not long before with his family and probably was in debt as a

result. He (presumably) had no nest egg that would allow him to

buy a plot of land, nor did he have wealthy friends like Thoreau did

who might let him squat on their land for free. What he did have

was several dependents, which added up to a lot more required fish than

Thoreau was reckoning on. (If you read the reviews on Amazon for Possum Living, you'll see similar

complaints about this more modern day manual of simple living.)

I believe that this passage

strikes to the heart of the problem with the voluntary simplicity

movement. The man whom Thoreau was lecturing had immigrated from

Ireland not long before with his family and probably was in debt as a

result. He (presumably) had no nest egg that would allow him to

buy a plot of land, nor did he have wealthy friends like Thoreau did

who might let him squat on their land for free. What he did have

was several dependents, which added up to a lot more required fish than

Thoreau was reckoning on. (If you read the reviews on Amazon for Possum Living, you'll see similar

complaints about this more modern day manual of simple living.)Although Mark and I tightened our belts in a lot of ways most middle class Americans wouldn't consider (for example, choosing in favor of trailer life and not to have kids), we also got lucky. I was about halfway through saving up the $10,000 I reckoned I'd need to buy ten Appalachian acres when a friend of mine came through with a no interest loan that allowed me to purchase a much larger acreage. My friend didn't ask for regular payments while we were spending every penny getting the farm up and running, so we only paid off the last of our debt this year, by which time local land prices had risen precipitously.

So here's the thought question for this week. Can you live simply if you're not at least culturally middle class? Anyone who wants to do further reading might consider the very readable Nickel and Dimed, which explores how hard it really is to live on minimum wage

if you're starting from

square one. I'll be curious to learn what you all think.

(And, as usual, feel free to also comment on other aspects of the

chapters not mentioned here.)

if you're starting from

square one. I'll be curious to learn what you all think.

(And, as usual, feel free to also comment on other aspects of the

chapters not mentioned here.)If you're new to the book club, you might want to check out the thought-provoking comments on chapter 1, chapter 2, chapters 3 and 4, chapters 5 and 6, and chapters 7 and 8. We'll be discussing chapter 11 (Higher laws) and chapter 12 (Brute neighbors) next Wednesday, and anyone is welcome to join in.

The paperback edition of Weekend Homesteader is full of fun and easy projects that guide you onto the path of self-sufficiency.

It only took our hired helper

about an hour to cut out and fabricate the above awesome barn door.

Now we can more easily store

straw bales in the barn where they'll feel more comfortable.

I love straw...

...and I love my new straw door. I call it the Secret

Door because our helper cut it straight out of the wall of the barn, so

the boards line up and you can hardly tell a door's there.

He added a few screws,

two hinges, a bit of a furring strip (for the latch), and a two by four

(to add structure and give the hinges someting to bite into).

Now I can stack my straw

inside and access it easily for the garden. (Or stockpile it for

later.)

It's been dry enough to haul,

so we're actually trying to stockpile all kinds of supplies. Our

helper told us about a straw opportunity that's presented a bit of a

conundrum, though.

It's been dry enough to haul,

so we're actually trying to stockpile all kinds of supplies. Our

helper told us about a straw opportunity that's presented a bit of a

conundrum, though.

His friend has dozens of

bales worth of loose straw in his barn to give away. The cows got

in and broke the bales apart and the friend just wants the biomass

gone. Sounds awesome, right?

The problem is that the

straw was grown in rotation with tobacco, which means it's probably

full of tomato

blight. I

honestly don't know enough about the blight fungi to determine how much

would be present on straw --- the fungi only live on members of the

tomato family, but they also stick around in the soil and could have

splashed up onto the straw during a rain. I also don't know how

far I'd need to keep the straw away from a tomato-growing area to

prevent adding more blight to our mix, or how deep in a kill mulch I'd

have to hide it.

So, do I want the free

biomass or not? I'm a bit too giddy with my straw door to think

straight right now. Maybe you can help me decide?

Those green

house tables will live on

as the Cadillac of worm bins.

The above worm enclosure went

together in about 3 hours.

We decided to put a layer of

shower board on the bottom, and a slanted lid should help the water run

off it better than our first

version that had a flat

top.

Mark

estimates that our

new garlic curing racks might save us about a week

of labor over the course of the next fifty years. I figure he's

not far off.

Mark

estimates that our

new garlic curing racks might save us about a week

of labor over the course of the next fifty years. I figure he's

not far off.

In previous seasons,

I've spent a lot of time hunting around in search of an area to cure

garlic, onions, sweet potatoes, and butternuts. I generally rig

something out of old screens my mom found by the side of the road, in

which case the trouble is ensuring the vegetables don't get rained on.

The drying racks our helper

built for us in the solar

tower take all of

the hunting and setup out of vegetable curing. The hardware cloth

bases are strong enough to hold quite a few heads of garlic, while

still allowing for plenty of air circulation, and the roof keeps out

the rain. (We very rarely have blowing rain --- if you do, you

might need to extend the roof.)

The drying racks our helper

built for us in the solar

tower take all of

the hunting and setup out of vegetable curing. The hardware cloth

bases are strong enough to hold quite a few heads of garlic, while

still allowing for plenty of air circulation, and the roof keeps out

the rain. (We very rarely have blowing rain --- if you do, you

might need to extend the roof.)

The only thing that

didn't quite work as planned is the two by four rungs that I planned to

climb up to put the vegetables in place. It was much easier to

simply lean a ladder against the side of the trailer and go up that

way, which felt much less precarious when I had an armload of garlic.

I'm not yet sure whether

we'll have enough surface area for all

of our crops, though. The garlic filled all six racks up to the

brim, and I

might need to cure onions before the garlic is ready to go into

bags.

We'll cross that bridge when we come to it.

It's a genuine thrill to have

all our blueberry

rows layered with cardboard and heavily mulched with 2 year old

wood chips.

Back when we installed

our package

of bees, a reader

admonished us to "FEED, FEED, FEED". The biggest question with a

package is...when to stop feeding. Our reader (Mike)

made the argument that you need to feed for at least seven weeks, since

that's how long it may take for the newly laid eggs to hatch out,

finish their duties as house bees, and then go out into the world to

gather nectar.

Other potential stopping

points some beekeepers use include:

- When the bees stop taking sugar water. This is dicey since some bees will keep sucking up sugar water even if there's a nectar flow.

- When the bees start to produce capped honey. I've used this guideline in the past, but it doesn't work so well for a Warre hive since I can't look inside to tell if there's capped honey.

- When you see the first orientation flight of new worker bees. Despite Mike's math, I started seeing new worker bees going out to forage about four weeks after package installation.

When you're in the middle of a nectar

flow. Our area has a summer lull at this time of year,

so if I used that standard, I might have to keep feeding until the

asters begin to bloom, or at least until my planted buckwheat

flowers. As you can see from the photos in this post, our bees

are currently going ga-ga over breadseed

poppies, but the bees are only getting pollen from that source.

When you're in the middle of a nectar

flow. Our area has a summer lull at this time of year,

so if I used that standard, I might have to keep feeding until the

asters begin to bloom, or at least until my planted buckwheat

flowers. As you can see from the photos in this post, our bees

are currently going ga-ga over breadseed

poppies, but the bees are only getting pollen from that source.

With so many

contradictory opinions on when to stop feeding bees, I thought I'd

submit the question to the internet hive mind. When do you take

away the sugar water and let your new package fend for itself?

In the past I've sometimes had 8 foot sheets of plywood cut

in half to make for an easier haul back to our home.

Our new helper clued us into

the side mount method. It only takes a minute to set up if you have the

right bungee cords and scrap wood.

Our readers are very kind not

to call us cuckoo for overbuilding

our worm bin when we

intentionally

underbuild so many

other parts of our farm. (Yes, that sentence is an excuse to

include this bird photo I took while trying to tempt our more skittish

cat out of a tree on

Friday.)

Our readers are very kind not

to call us cuckoo for overbuilding

our worm bin when we

intentionally

underbuild so many

other parts of our farm. (Yes, that sentence is an excuse to

include this bird photo I took while trying to tempt our more skittish

cat out of a tree on

Friday.)

The main incentive for

building an elegant worm bin that will last a hundred years is that we

had some hefty,

free lumber lying

around. But we also decided to take the opportunity to correct

the problems we've noticed in midscale

worm bin version 1.0 over the last year. That's the great

thing about underbuilding the first time around --- you generally get a

second stab at the problem a few years later once you've figured out

exactly how you want to tweak the project to fit your own needs.

(Verison 1.0 is still in

use, by the way --- the Cadillac is merely an expansion of the

vermiculture operation. I'll give you more details of what's

going inside both bins in a later post.)

You can see a

supply list and construction notes for our first midscale worm bin here. Version 1.0 was

quick, dirty, and cheap and it (mostly) worked, but the design was

clearly flawed. I thought I'd be able to collect

worm tea, but in

reality, this large worm bin didn't make any liquid (or at least not

enough to collect), so we ditched the false bottom when making our

second bin. Meanwhile, Mark got the bright idea of adding

showerboard to the floor of version 2.0 in hopes of delaying wood rot

in this dampest portion of the bin. Since we didn't want to

pierce the showerboard, that left us without aeration

You can see a

supply list and construction notes for our first midscale worm bin here. Version 1.0 was

quick, dirty, and cheap and it (mostly) worked, but the design was

clearly flawed. I thought I'd be able to collect

worm tea, but in

reality, this large worm bin didn't make any liquid (or at least not

enough to collect), so we ditched the false bottom when making our

second bin. Meanwhile, Mark got the bright idea of adding

showerboard to the floor of version 2.0 in hopes of delaying wood rot

in this dampest portion of the bin. Since we didn't want to

pierce the showerboard, that left us without aeration  holes, so our helper

suggested spacing the boards that make up the sides about a quarter of

an inch apart to give lots of room for air movement.

holes, so our helper

suggested spacing the boards that make up the sides about a quarter of

an inch apart to give lots of room for air movement.

From a purely ergonomic

standpoint, I seldom opened version 1.0 because an 8 by 4 foot sheet of

plywood was simply too heavy and ungainly for me to easily handle, even

on hinges. So our helper split the lid on this new worm bin into

thirds, adding braces to the inside of the bin to prevent the second

lid problem we'd noticed --- warping of the plywood. (You can see

the lids well in the top right photo in this post.)

So

far, the only slight problem I've had with the bin is opening the

middle lid --- my arms aren't quite long enough to really open it all

the way. I suspect we'll find more flaws as we use the bin, and

will make version 3.0 even more efficient. For the moment,

though, Mark and I are both so pleased with our Cadillac worm bin that

we go visit it from time to time and I even dreamed about it Thursday

night. Quite a lot of excitement for our quiet farm!

Imagine how ecstatic we'll be when we actually seed the bin with worms.

So

far, the only slight problem I've had with the bin is opening the

middle lid --- my arms aren't quite long enough to really open it all

the way. I suspect we'll find more flaws as we use the bin, and

will make version 3.0 even more efficient. For the moment,

though, Mark and I are both so pleased with our Cadillac worm bin that

we go visit it from time to time and I even dreamed about it Thursday

night. Quite a lot of excitement for our quiet farm!

Imagine how ecstatic we'll be when we actually seed the bin with worms.

Our pre-made

automatic chicken coop door

is coming up on its one year anniversary next month and is still going

strong.

I noticed a new DIY approach

this morning from Phillip Reed that captures my attention for

multiple reasons.

1. Parts are common and low

cost.

2. Design seems solid, safe,

and long lasting.

3. He offers detailed

instructions in Ebook or paperback.

In my opinion Jeremy at AutomaticChickenCoopDoor.com is still the best option for

those who want an out of the box solution that is ready to go in

minutes, but the above design might be a good place to start for those

do it yourselfers who have a little extra time to tinker on such a

project. I would imagine Phillip Reed's instructions could end up

saving 4 or 5 hours of trial and error depending on building

skills.

--- Maurice Grenville Kains in Five Acres and Independence

We don't have this

problem (except possibly during strawberry

week). Even

the hungriest city dweller is generally deterred by the alligator swamp.

Luckily, I'm becoming

better and better at tempting true friends to make the trek, bringing

me closer to my goal of never leaving the farm but still keeping in

touch. Heather is one of our favorite

visitors, and I totally lost track of time while chatting with her on

Saturday. (We both just thought it was getting cloudy...not dark.)

Thanks for coming,

Heather! And don't forget that guest post you promised me about

books for the beginning gardener.

It's that season again

--- time to send Egyptian onion top bulbs out to take over the

world! I've already given away two brimming bagsful, but as you

can tell, there are still plenty left.

(If you've never met

these delightful perennial onions, you can read more about

them here.

There are no purchase buttons on that page because I think I'm going to

save all of  the onion bulbs to give away

this year, unless my readers get sated and stop taking them.

Speaking of which, if you're someone I see in person and would like

some Egyptian onions for your garden, just drop me an email and I'll

set aside some for you before I give the rest away.)

the onion bulbs to give away

this year, unless my readers get sated and stop taking them.

Speaking of which, if you're someone I see in person and would like

some Egyptian onions for your garden, just drop me an email and I'll

set aside some for you before I give the rest away.)

To be entered in our

Egyptian onion giveaway, download

Microbusiness Independence from Amazon today, then leave a comment

on this post to let me know you've entered. I've set it up so our

oldest ebook is free today

and tomorrow, so

this is a great opportunity to learn our tips on becoming financially

self-sufficient.

Rather

than selecting only one winner, I'll choose five commenters at random

to win a small flat rate box full of Egyptian onion top bulbs.

This is enough to feed a large family all of the green onions they can

eat, or to spread some starts around to your gardening buddies.

Rather

than selecting only one winner, I'll choose five commenters at random

to win a small flat rate box full of Egyptian onion top bulbs.

This is enough to feed a large family all of the green onions they can

eat, or to spread some starts around to your gardening buddies.

Be sure to comment by

midnight on Tuesday, June 12, and then check the comments on Wednesday

to see whether you won. Our Egyptian onions are looking forward

to exploring their new homes!

The Stihl FS-90R trimmer/weed eater has been with us for about a year

now and still starts on the first or second try. We made a bit more

progress on reclaiming

the gully today thanks to its power.

I recently considered

upgrading the grip to what Stihl calls a "Bike handle". I heard

there was a conversion kit, but our local Stihl dealer said that for an

extra 40 dollars from what the kit cost you could buy a whole trimmer

with the bike handle installed and ready to go.

She also told me that bike

handle grips are good for level situations where you find yourself

"mowing" for long stretches of time, but if you've got hills then the

two handed grip tends to wear on your back more than the loop handle.

We've got plenty of elevated weeds here, which is what convinced me to

forget about the bike handle.

A lot of people buy an Austrian

scythe because they want to replace their weedeater and/or

lawnmower with a hand tool. Why use gasoline when you don't have

to?

A lot of people buy an Austrian

scythe because they want to replace their weedeater and/or

lawnmower with a hand tool. Why use gasoline when you don't have

to?

Although I agree with

that logic to some extent, Mark has turned me into a realist when it

comes to homesteading tools. If a hand tool takes a significant

amount more muscle than a power tool, I might choose the power tool.

On the other hand, I

also factor in the long term effort involved. If I'm afraid of

the power tool, can't get it started easily, or can't fix common

ailments myself, I might find it simpler in the long run to use a hand

tool. That's why our

tool kit contains a mixture of power and hand tools, into which the scythe slid

gracefully.

So which power tools

does the scythe replace, and when? Pros use their scythe to mow

the lawn, but I have to admit that I find the lawnmower much easier in

that respect. On the other hand, the scythe is great on rough

terrain or when cutting tall weeds that would bog down the mower.

There, Mark would turn to the weedeater, but that tool fails all

three of my power tool tests, so I stick to the scythe. (Despite

being scared of the weedeater, I wouldn't try to use my scythe for the

tasks Mark turns his ninja

blade to --- really

heavy duty brush is a job either for power tools or for slow and steady

work with loppers and a hand saw.)

Even if you like your

weedeater, you might find a scythe handy in certain situations.

Scythes cut right where you tell them to without shredding the severed

plant to bits, so they're great for harvesting grain and cutting

comfrey for mulch.

My scythe also makes it easy to mow with more discernment, a boon in my

complicated forest gardens and pastures, where I might want to leave a

berry plant to finish fruiting, mow red clover at six inches but

ragweed right at the ground, and be able to feel that I'm hitting a

fallen branch before damaging my tool.

Even if you like your

weedeater, you might find a scythe handy in certain situations.

Scythes cut right where you tell them to without shredding the severed

plant to bits, so they're great for harvesting grain and cutting

comfrey for mulch.

My scythe also makes it easy to mow with more discernment, a boon in my

complicated forest gardens and pastures, where I might want to leave a

berry plant to finish fruiting, mow red clover at six inches but

ragweed right at the ground, and be able to feel that I'm hitting a

fallen branch before damaging my tool.

(I can't say for sure

that a weedeater can't do all those things --- I've hardly used

one. But I can tell you for sure that it's easier for me to

scythe my complex pastures than to explain to Mark how I want them cut.)

Now for the downsides of

the scythe. You need to commit more time to learning the craft,

paying special attention to sharpening the blade. On the other

hand, while you can just start a weedeater and let her rip, you'll

still have to take the tool in for a tuneup from time to time if you

can't figure out how to clean the air filter, change the spark plug,

etc.  In the long run, I think that

a scythe requires less knowledge to keep the tool running at its best

than a weedeater does, unless you're already an expert at small engine

repair.

In the long run, I think that

a scythe requires less knowledge to keep the tool running at its best

than a weedeater does, unless you're already an expert at small engine

repair.

I was also disappointed

to discover that scything is very wrist intensive. I'm prone to

carpal tunnel flareups, which is why Mark splits all the wood around

here. While not nearly as bad for my tendons as splitting wood,

half an hour of scything is really all my wrists can handle before they

begin to protest. This is a problem because scything is extremely

addictive and fun, and it's hard to make myself stop once I've started!

I'm sure I'll discover

additional pros and cons of the scythe as I use it more. I

haven't quite put in the eight hours required before I need to peen the

blade yet, so take my advice with a grain of salt. Maybe other

scythe-users will chime in with the times they choose to (and not to)

use their scythe.

A small breeze on a hot day

can sometimes feel like a gift from the wind gods.

I was a bit dubious of the

clip on solar hat fan, but it looked so cool I decided to get two.

The fan is weak, but you do

feel wind blowing right up close where it counts the most. The sound

might annoy some folks, but a loud lawn mower and ear plugs can fix

that. A wide brim hat allows for 360 degrees of placement choices, but

it also works with a more conventional baseball cap.

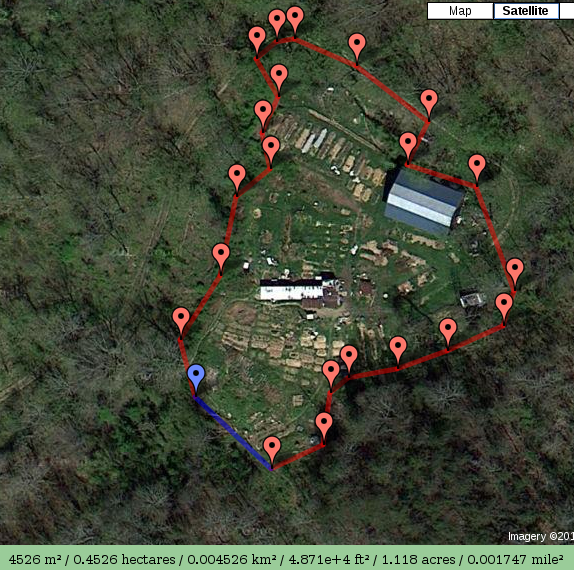

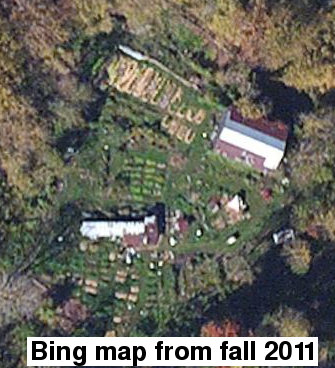

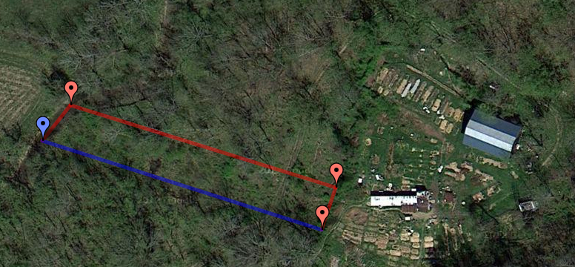

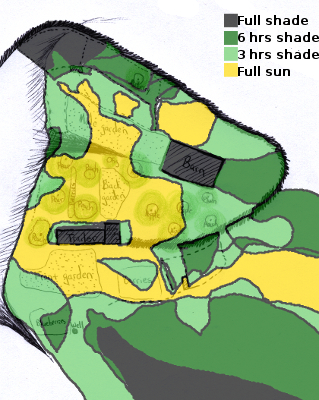

Thanks to google planimeter (and some awesome new maps,

updated this April!), I can answer Roland's

question about how much land we use to grow our own food. The map above shows

our total footprint on the land (minus our driveway, hunting area, and

woodlot, but including the house and barn) --- 1.118 acres.

Here's a breakdown of

the purposes to which we put that land:

| Use |

Acres |

Pastures:

|

0.1371 |

Vegetable gardens (including

strawberries and potatoes):

|

0.23275 |

Forest garden:

|

0.16535 |

Berries

|

0.04779 |

These

numbers only add up to about half the total acreage of our core

homestead because they don't include areas like the gully, trailer,

barn, woodshed, water tank, etc. That said, I have included

paths, both for people and for the golf cart.

These

numbers only add up to about half the total acreage of our core

homestead because they don't include areas like the gully, trailer,

barn, woodshed, water tank, etc. That said, I have included

paths, both for people and for the golf cart.I did some extra math, which I'll post on our chicken blog next week, and came to the conclusion that we outsource 0.36486 acres of growing land to the producers of our chicken feed, and perhaps that or a little more to the growers of our straw. Since you get both straw and grain from the same field, I'm not counting the straw figures into our land area. Nor am I counting the acreage on which the horses who give us our manure graze since manure is considered a waste product of their operation.

We still buy a lot of fruit,

but that's because our orchard is young. I think our current forest garden

and berry patches will sate even my frugivorous appetite once

everything is mature. We will probably expand our berries a bit

more to fill in gaps, though.

We still buy a lot of fruit,

but that's because our orchard is young. I think our current forest garden

and berry patches will sate even my frugivorous appetite once

everything is mature. We will probably expand our berries a bit

more to fill in gaps, though.More relevantly, we buy red meat from a friend, and I don't have any data on how much land and grain she uses to produce that meat --- maybe another half acre? I'm not going to factor in the small amount of dairy products, flour, peanut butter, nuts, cocoa, sugar, and spices we get from the store --- that's beyond my math skills and we could do without if need be. (Except the chocolate -- can't do without that!)

So, to answer Roland's question, if we grew our own chicken feed but stopped eating everything else from the store, we'd be using just shy of half an acre (0.2 hectares) apiece to feed ourselves. This is the exact amount of arable land per person Roland estimates the world currently contains. I'm pretty sure whoever came up with those numbers didn't include steep grazing land in their arable land figures, so Mark could probably get away with adding in his red meat by raising sheep on the hillside. (Actually, I'm not so sure that any part of our property was included in the arable land estimate.)

I was thrilled by the

interest in our Egyptian onion giveaway! Zoe, Charity, Jeff,

Denise, and Jeremiah --- please drop an email to anna@kitenet.net and I'll put

your onions in the mail to you Friday.

For everyone else who

entered, I'll see how many onions are left once I box those up and will

consider another giveaway. My father has kindly offered me his

top bulbs (from descendants of my onions, of course) to spread the

species yet further, so we may have enough between us for another

giveaway. Stay tuned!

There's

so much to talk about in chapters 11 and 12 of Walden that I'm not quite sure

where to focus my energy. I could take the easy way out and write

about chapter 12, how the mouse that Thoreau befriended is like the

tree frog that lives beside our spigot and the phoebes we watch heading

into the barn with bugs for their chicks. Or I could go in the

opposite direction and tear apart Thoreau's belief that "all sensuality

is one; all purity is one", by which he means that in order to be

spiritually pure, we have to mortify our senses with plain food and

drink and complete chastity.

There's

so much to talk about in chapters 11 and 12 of Walden that I'm not quite sure

where to focus my energy. I could take the easy way out and write

about chapter 12, how the mouse that Thoreau befriended is like the

tree frog that lives beside our spigot and the phoebes we watch heading

into the barn with bugs for their chicks. Or I could go in the

opposite direction and tear apart Thoreau's belief that "all sensuality

is one; all purity is one", by which he means that in order to be

spiritually pure, we have to mortify our senses with plain food and

drink and complete chastity.

But I'll instead take

the middle road and write about a tangential topic that I found more

interesting:

"...when some of my friends have

asked me anxiously about their boys, whether they should let them hunt,

I have answered, yes, --- remembering that it was one of the best parts

of my education --- make them

hunters..."

"...when some of my friends have

asked me anxiously about their boys, whether they should let them hunt,

I have answered, yes, --- remembering that it was one of the best parts

of my education --- make them

hunters...""We cannot but pity the boy who has never fired a gun; he is no more humane, while his education has been sadly neglected. This was my answer with respect to those youths who were bent on this pursuit, trusting that they would soon outgrow it."

In fact, Thoreau believed

that he owed his own deep appreciation of nature to a boyhood spent

with a gun in his hands. He wrote that hunting and fishing "early

introduce us to, and detain us in a scenery with which otherwise, at

that age, we should have little acquaintance."

In fact, Thoreau believed

that he owed his own deep appreciation of nature to a boyhood spent

with a gun in his hands. He wrote that hunting and fishing "early

introduce us to, and detain us in a scenery with which otherwise, at

that age, we should have little acquaintance."Long-time readers of the blog will know that I've gone through an extensive series of thought processes about hunting. When I was in elementary school and lived on my parents' farm, our closest neighbor would go out and kill turkeys and deer, and we kids would vilify him for it, calling him Gargamel. (Gargamel is the evil enemy of the smurfs, in case you didn't watch the same cartoons I did as a child.)

Soon

after college, I spent a few years wandering around peoples' land

telling them what plants and animals they had, and I began to realize

that the hunters I bumped into were (usually) more in tune with the

wild areas than the city folks who came out to enjoy my interpretive

hikes. The latter liked the easy and fun ecological stories, but

the hunters had a deeper appreciation for the entirety of the

ecosystem, along with a vested interest in the land that made them want

to protect it. (I also decided that hunting was an excuse for

macho men to spend time looking at butterflies and flowers without

being deemed sissies, but that's not as relevant to this post.)

Soon

after college, I spent a few years wandering around peoples' land

telling them what plants and animals they had, and I began to realize

that the hunters I bumped into were (usually) more in tune with the

wild areas than the city folks who came out to enjoy my interpretive

hikes. The latter liked the easy and fun ecological stories, but

the hunters had a deeper appreciation for the entirety of the

ecosystem, along with a vested interest in the land that made them want

to protect it. (I also decided that hunting was an excuse for

macho men to spend time looking at butterflies and flowers without

being deemed sissies, but that's not as relevant to this post.) Years later, I learned to kill, gut,

and cook deer that

wandered into our garden. I slowly morphed from being a pure

preservationist who believed that the best thing humans could do to

nature is to fence it off and leave it alone, to a permaculturalist who

believes that humans are a part of nature --- still bound to protect

it, but from within, not from without. In the process, I felt

like I developed a deeper appreciation for wild things, and an

acceptance that nature doesn't have to resemble a museum-perfect

painting to be valid.

Years later, I learned to kill, gut,

and cook deer that

wandered into our garden. I slowly morphed from being a pure

preservationist who believed that the best thing humans could do to

nature is to fence it off and leave it alone, to a permaculturalist who

believes that humans are a part of nature --- still bound to protect

it, but from within, not from without. In the process, I felt

like I developed a deeper appreciation for wild things, and an

acceptance that nature doesn't have to resemble a museum-perfect

painting to be valid.While those epiphanies probably would have come anyway if I'd never picked up a gun, I suspect that Thoreau is right that hunting can help speed the nature appreciation process along. What do you think? Would you rather have Junior playing video games on the weekend, or out hunting squirrels on the back forty? Is nature better appreciated from within, or from without?

If you're new to the book club, you might want to check out the thought-provoking comments on chapter 1, chapter 2, chapters 3 and 4, chapters 5 and 6, chapters 7 and 8, and chapters 9 and 10. We'll be discussing chapter 13 (House-warming) and chapter 14 (Former inhabitants; and winter visitors) next Wednesday, and anyone is welcome to join in.

The paperback edition of Weekend Homesteader is full of fun and easy projects that guide you onto the path of self-sufficiency.

The current chicken

pasture I'm working on is a challenge due to 90 percent of it being

on a steep hill.

It should make it harder for

deer to find their way down to us. I would guess over half of all our

deer incursions came from this direction.

We planted a cherry bush in

this area which is looking good and should be an excellent source of

protein for our flock once the cherries start dropping.

Our farm grows wingstem

and ragweed better than anything

else. Although our honeybees visit the flowers, we don't get

any other products from these acres and acres of

wildflowers...until now.

The tall weeds that line our

driveway have always looked like an opportunity, but I never could

figure out what they were an opportunity

for. One winter, I gathered the dead stalks and sent them through

our shredder/hammer

mill, but the

process took forever and I was worried that the seedy mulch would cause

problems.

The tall weeds that line our

driveway have always looked like an opportunity, but I never could

figure out what they were an opportunity

for. One winter, I gathered the dead stalks and sent them through

our shredder/hammer

mill, but the

process took forever and I was worried that the seedy mulch would cause

problems.

At this time of year,

though, ragweed and wingstem are shooting up fast and have no flowers

or seeds in sight. Add in the scythe and a bed of raspberries

that the chicks had scratched nearly bare, and I thought I might have

figured out my opportunity.

It took me about an hour

(and two big golfcart loads) to cover up the cardboard of my kill mulch

with a new organic layer. I mulched very thickly since I know the

weed leaves will wilt down to nearly nothing, but I hope the stems will

be enough to provide a long-lasting mulch. That means it took

just a bit longer to mulch the row than if we'd hauled buckets

of composted wood chips from the parking area, but only about half as long

as raking

leaves out of the woods.

The trick to speedy weed

gathering was to hit spots right along the driveway where partial shade

keeps the vines down and allows the scythe to make short work of the

weed stalks. Actually, I spent a lot more time collecting the

weeds off the ground than cutting them down, meaning that if I wanted

to build a grain

cradle for the

scythe, I could probably become significantly more efficient.

The trick to speedy weed

gathering was to hit spots right along the driveway where partial shade

keeps the vines down and allows the scythe to make short work of the

weed stalks. Actually, I spent a lot more time collecting the

weeds off the ground than cutting them down, meaning that if I wanted

to build a grain

cradle for the

scythe, I could probably become significantly more efficient.

I also suspect that I'd

get more biomass for my effort if I waited another few weeks until the

weeds were starting to bloom. At that stage, they'd be higher in

carbon, which would make the mulch last longer while encouraging

beneficial fungi in the soil. Right now, the shaded wingstem and

ragweed in the woods are between three and five feet tall, but they'd

be bigger at bloom time.

I'll try to remember to

report back once I get an idea about how well the weeds work as

mulch. I'll probably repeat the experiment in a few other patches

in the meantime --- scything combined with the golf cart is too much

fun to pass up.

The chicken

cherry pasture got a little bit more fenced in today.

I started out this morning

using the solar

clip on hat fans, but took them off because of the noise. It's not

that the fan is really all that loud, but it's very close to your ear and it

makes it hard to hear if someone is talking to you. It was also messing

with my normal, tranquil, happy feeling by reminding me of a brief job

where I worked at an extremely loud spring factory in Xenia Ohio.

My conclusion is that the

solar clip on hat fans are awesome when mowing or running similar

equipment where the fan noise gets drowned out by a louder machine.

Lee Reich's The

Pruning Book is

worthy of a lunchtime series, but it's summer, so you'll just get a

review with a few choice tidbits. I thoroughly enjoyed the book,

from the structure (30 pages on pruning basics, then sections on each

type of plant you might want to prune) to the visuals (which include

both informative drawings and photographs). I've always liked Lee

Reich's method of researching and presenting facts, but still inserting

bits and pieces of personal experience, and this book was no exception.

Lee Reich's The

Pruning Book is

worthy of a lunchtime series, but it's summer, so you'll just get a

review with a few choice tidbits. I thoroughly enjoyed the book,

from the structure (30 pages on pruning basics, then sections on each

type of plant you might want to prune) to the visuals (which include

both informative drawings and photographs). I've always liked Lee

Reich's method of researching and presenting facts, but still inserting

bits and pieces of personal experience, and this book was no exception.

None of the information

in The

Pruning Book is particularly earth-shattering, and you can find most or

all of it on extension service websites. In fact, that's how I've

been garnering my pruning information so far --- in bits and pieces

from short articles. However, reading the same information in

book form, I connected dots I hadn't realized needed to be connected,

for example realizing that pruning a hedge follows many of the same

rules as pruning a fruit tree. In both cases, you need to start

training the plants during the first year, and to prune so that light

hits all parts of the plant. (As a side note, The

Pruning Book has more information on

hedges, pollarding, and espaliers than I'd found anywhere else.)

Do you understand why a

heading cut makes plants bush out while a thinning cut merely redirects

energy to existing limbs? Did you know that thinning young fruits

not only ensures the remaining fruits are larger, but also that the

tree doesn't decide to skip fruiting next year? I'll regale you

with more tidbits as I summer prune our orchard and berry patch over the course of the next week.

Although I suspect I'll

outgrow this book in two or three years, at the moment it's found a

place on my permanent bookshelf. Now, if I could just find an equally good book about grafting....

It felt good to finish up the

fencing on the new chicken

cherry pasture today.

I think I've got all the

bottom gaps closed up, but the real test will be to let the flock forage through it to see if any of them get out.

Although we've only had

it for a short while, I can tell the Warre hive is good for my beekeeping

skills. I never even considered taking

photographs through the screened bottom of my Langstroth hives

because I knew I could just take the boxes apart whenever I felt like

it, but the camera and I have been making regular visits to the Warre

hive to see what's going on inside. Lately, I've taken to

pressing my ear up against each box too, which gives me an indication

of where the bees are actively working. All of this data without

bothering the bees at all!

Just this week, the colony

has finally moved down into the new

box we gave them three weeks ago. The slow movement

downward tells me that my weight-based guess was right --- the bees

hadn't worked on the top box yet at the time we nadired a new box

underneath.

Just this week, the colony

has finally moved down into the new

box we gave them three weeks ago. The slow movement

downward tells me that my weight-based guess was right --- the bees

hadn't worked on the top box yet at the time we nadired a new box

underneath.

Listening at the hive

Friday morning, the bottom box roared with bees building comb, the

second box roared with bees feeding brood, and the top box produced

more of a gentle growl. I suspect that the bees are using their

attic to dehydrate nectar into honey, thus the lower activity levels up

top.

In other bee-related

news, I never did make a decision about how

long to feed our package of bees. As a result, I'm

splitting the difference between the two extremes by letting the colony

wait a day or two after each infusion of sugar water. The white

clover is blooming pretty well, but it's been awfully dry here for the

last couple of weeks, and I'm just not sure how much nectar the flowers

are producing. My first buckwheat cover crop will probably start

blooming in a week or so, at which point, I might cut the bees off

their sugar water.

Our flock was a bit timid

about exploring their new free

range chicken pasture this morning, but after an hour of coming out

and running back in it seems they've decided to make themselves at home.

External deadlines make

me nervous, so I try to avoid them at all costs. When I was in

college, I was the one who wrote my paper the weekend before even

though it wasn't due  until Friday, and I now weed

and topdress new garden beds the week before they're supposed to be

planted so that the seasonal deadline doesn't creep up on me.

until Friday, and I now weed

and topdress new garden beds the week before they're supposed to be

planted so that the seasonal deadline doesn't creep up on me.

But sometimes you can't

avoid deadlines, and this weekend is one of those times. My

editor emailed me the final draft of The Weekend

Homesteader for

corrections, due Monday. Sure, I could have argued that I wrote

into my contract that I had a month for this stage (mostly because I

thought they'd mail proofs and I was afraid a flood might slow things

down). But I'd rather have the manuscript zip over to China ASAP

so the presses will start rolling.

So I've broken one of our

farm's cardinal rules and am working during the weekend.

(Watering the forest garden by hand too, to give me a break between

chapters.) Now that I'm 75% of the way done, the stress of an

external deadline is finally lifting off my shoulders, but I don't

think I'll have any extra deep thought to spare once I get the book off

my plate.

So I've broken one of our

farm's cardinal rules and am working during the weekend.

(Watering the forest garden by hand too, to give me a break between

chapters.) Now that I'm 75% of the way done, the stress of an

external deadline is finally lifting off my shoulders, but I don't

think I'll have any extra deep thought to spare once I get the book off

my plate.

Which is all a long way

of saying --- we're taking a week's vacation from Walden.

I hope you don't mind the extension. Go enjoy your garden instead!

Still no no signs of deer

damage to the garden this year.

I finally got around to

upgrading the solar

powered deer deterrent from the Alkaline D cell to a pair of

rechargeable AA batteries just in case we need a mechanical deer

deterrent on short notice.

The batteries were a little

undercharged at only 1.2 volts, but I'm trying a series circuit which

will double that to 2.4 volts DC. My thinking is that the motor stops

turning just under 1.3 volts, and even though it turns a bit faster

with 2 batteries it's not too fast and the increase should help boost

the longevity factor.

You

may recall that we've done several experiments with worm bins. In

2009, we had a small,

under-the-sink worm bin, which dwindled away because

we gave all of the worm-worthy scraps to the chickens, except for the

one thing chickens won't eat --- citrus peels. Unfortunately,

citrus peels also turned out to be the one fruit scrap that kills worms.

You

may recall that we've done several experiments with worm bins. In

2009, we had a small,

under-the-sink worm bin, which dwindled away because

we gave all of the worm-worthy scraps to the chickens, except for the

one thing chickens won't eat --- citrus peels. Unfortunately,

citrus peels also turned out to be the one fruit scrap that kills worms.

We started again last

year with an ambitious project of collecting food scraps from a local

school to feed a larger worm bin. That

project failed for various reasons, so we filled the bin back

up with horse manure and  bedding, which resulted in

some great

worm castings this

spring. (We got another ten buckets of castings between the time

I wrote that post and the time I'm writing this one.)

bedding, which resulted in

some great

worm castings this

spring. (We got another ten buckets of castings between the time

I wrote that post and the time I'm writing this one.)

But, once again, I made

some mistakes. We located our large worm bin out by the parking

area --- perhaps a third of a mile from our core homestead --- because

we wanted to be able to put food scraps into it from the school even

when the driveway was impassable. In permaculture terms, I think

of the parking area as zone 3 or 4, and a worm bin is more of a zone 1

or 2 project. Worms don't need as much care as your chickens or

vegetables, but good vermiculturists probably open the lid at least

once a week.

The result of placing

the bin so far from home is that it got neglected. I should have

refilled the bin early this spring with fresh manure, which would have

tempted the worms to reproduce and expand from their small winter

population. Instead, they were looking for food in their own

waste, and the number of worms dwindled yet further. There were

still enough  worms present to seed the new

manure we added to the bin a couple of weeks ago, but not enough worms

to move some to our new

Cadillac worm bin.

worms present to seed the new

manure we added to the bin a couple of weeks ago, but not enough worms

to move some to our new

Cadillac worm bin.

So we bought more

worms. We'd lost the contact information for our

local supplier, so

settled on buying two pounds of worm castings online. That's not

nearly enough worms for such a huge bin, but I don't really need the

castings until next spring, so I figure they've got plenty of time to

fill the space. I also added some soaked, shredded paper since

the horse manure smelled a bit like ammonia, a sign that it doesn't

have enough carbon and is outgassing precious nitrogen into the air.

(I also figured the paper would give the worms a safe place to hide if

the relatively fresh manure gets too hot for them.)

Meanwhile, Mark talked

me into building more worm bins (with the number yet to be determined)

as a way of stockpiling compost so that it improves with age. We

never  know when we'll be able to

drive biomass in and when we won't, so it's a good idea to work ahead,

but it's just sad to see last year's manure piles sink into the ground

before they can feed the garden.

know when we'll be able to

drive biomass in and when we won't, so it's a good idea to work ahead,

but it's just sad to see last year's manure piles sink into the ground

before they can feed the garden.

Even Mark blanched,

though, when I told him it would take at least ten big worm bins to

ensure I had enough compost for a solid year. Maybe we'll just

build another one or two for now....

We had our helper build

another worm

bin today.

He took some initiative and

improved the lid so it can easily be held up with the above side pieces.

It's the best worm bin yet,

and we still plan to build more.

My topworked

pear trees were a

spectacular failure. The trees came down with fireblight, and I

stuck my head in the sand so long they managed to pass the bacteria on

to the apple trees.

I started out blaming

the scionwood source since we'd never had fireblight on our farm

previously. However, some research made me rethink that and start

pointing the finger back at myself. It turns out that extremely

heavy pruning makes it far more likely you'll get fireblight in your

trees, and my topworking involved some very heavy pruning. (I'm

surprised the information I read on topworking pears didn't include

that warning, but I guess the websites were geared at commercial

orchards who spray antibiotics.)

Meanwhile, something about

the spring weather also seems to have promoted fireblight. My

sister called me to say that her pear trees 90 miles away are so badly

fireblighted, she might have to cut them down. Like me, she'd

never seen fireblight on her farm before, and she didn't do any crazy

topworking. So it's possible that the disease would have struck

whether I pruned heavily or not.

Meanwhile, something about

the spring weather also seems to have promoted fireblight. My

sister called me to say that her pear trees 90 miles away are so badly

fireblighted, she might have to cut them down. Like me, she'd

never seen fireblight on her farm before, and she didn't do any crazy

topworking. So it's possible that the disease would have struck

whether I pruned heavily or not.

Better late than never,

I pruned out all of the damaged branches. But I still might have

to cut my pear trees down too since the trunks have lesions all the way

to the ground. I'd just assumed one of our cats was using the

trunk as a scratching post, but closer examination suggests the wounds

are more likely to be another symptom of fireblight.

The good news is that

the phoebe pictured at the beginning of this post seems to be taking a

major dent out of our Japanese

beetle population

this year. A pair of the insect-eating birds is nesting in the

barn, right next door to our grapes (also known as "Japanese beetle

mecca"). In previous years, I've picked huge numbers of beetles

off the row of grapes, but this year there only seem to be a few

beetles...and lots of bird droppings. If only the phoebes would

head over to the raspberries and continue their good work!

Our helper Bradley was kind

enough to bring his gun cleaning kit over today and gave us a crash

course in proper cleaning procedures.

I've heard some folks say you

can use WD-40 to clean a gun. Bradley says that will work in a pinch,

but WD-40 tends to attract dust and lacks a teflon component that most

gun oils have.

Although I've killed

two deer, I wasn't

raised with guns and have a sinking feeling I'm missing some important

safety points. So I was thrilled when our new helper (who said we

can start using his name: Bradley) brought his

gun-cleaning kit and

showed us how to keep our tools in good working order.

Although I've killed

two deer, I wasn't

raised with guns and have a sinking feeling I'm missing some important

safety points. So I was thrilled when our new helper (who said we

can start using his name: Bradley) brought his

gun-cleaning kit and

showed us how to keep our tools in good working order.

Except for needing some

special lubricants and a $20 cleaning kit, the procedure didn't look

all that daunting. Bradley wiped the guns down, cleaned out the

barrels (both with a soft swab and with a twisted wire brush that gets

powder out of the grooves), and sprayed a bit of lubricant inside to

sit overnight. He told me that (with a plain old rifle, not a

muzzle-loader), he cleans his guns twice a year when they're not in

use, then quickly cleans the barrel after every tenth bullet or so.

Bradley had good advice

for improving my marksman skills as well. I hardly practice

because the bullets for our 40 caliber rifle are expensive, so he

recommends a 22 rifle for target  shooting. He also

promised to come by the next time we shoot a deer and teach us the

field dressing methods he learned at his father's knee, which get the

meat in the freezer in 15 minutes flat.

shooting. He also

promised to come by the next time we shoot a deer and teach us the

field dressing methods he learned at his father's knee, which get the

meat in the freezer in 15 minutes flat.

In other blood-thirsty

news, a couple of weeks ago, we saw a rabbit in the garden for the

first time in years. The rabbit got scared and ran into the

chicken pasture, where the poor thing battered itself against the

corner in vain. I wanted to kill it and see what rabbit meat

tastes like, but wasn't sure if that was legal out of season.

I emailed the Virginia

Department of Game and Inland Fisheries with my question, and they

wrote back:

The issue of

out-of-season rabbit hunting is actually up for interpretation in

Virginia due to the complexity of the rule book, but if the officials

say I can kill rabbits out of season on my land any way I want, I'm not

going to look that gift rabbit in the mouth. The next bunny in

the garden will have to beware. (We'll probably try to live trap

it instead of shoot it, though. I don't think I'm a good enough

shot to kill a running rabbit.)

My

Side of the Mountain

by Jean Craighead George was one of my favorite books twenty-some years

ago. Since I'm taking a quick vacation from

Walden, I couldn't

resist rereading this fictional account of a boy who follows in

Thoreau's footsteps and carves a livelihood out of the woods.

My

Side of the Mountain

by Jean Craighead George was one of my favorite books twenty-some years

ago. Since I'm taking a quick vacation from

Walden, I couldn't

resist rereading this fictional account of a boy who follows in

Thoreau's footsteps and carves a livelihood out of the woods.

With adult eyes, I see