archives for 05/2012

The

bad news is --- the package

of bees we put in

the top bar hive Friday absconded

Monday. They only ate half as much sugar water as the other hive,

which should have tipped me off that something was wrong, but I didn't

realize there was a problem until I saw that the hive was empty and all

of the bees were clinging to the trunk of a nearby tree.

The

bad news is --- the package

of bees we put in

the top bar hive Friday absconded

Monday. They only ate half as much sugar water as the other hive,

which should have tipped me off that something was wrong, but I didn't

realize there was a problem until I saw that the hive was empty and all

of the bees were clinging to the trunk of a nearby tree.

We tried to brush the

mass of bees (technically not a swarm, but they act like one) into a

bucket to be rehived, but I suspect the queen took flight because all

of the bees flew right back out and disappeared. So, we're down

to one hive and I'm trying to figure out why our bees flew the coop.

Searching around the

internet, I ran across these possible causes for absconding:

- Frequent disturbance.

I thought that since opening the observation

window didn't mess with the hive, I could look as often as I

wanted. But now I'm wondering whether the light coming in during

my frequent viewings didn't bother the bees and make them think their

colony was unsafe. Similarly, I left the screened

bottom completely open for ventilation, but that made it pretty

bright inside the hive --- perhaps I should have closed the bottom and

minimized my viewings for the first couple of weeks?

- Top bar hive. When

I read The

Barefoot Beekeeper, I remember the author recommending against

packages as a way of starting top bar hives.

But packages are the most prevalant way of getting new bees in the

U.S., so I ignored the author's advice. My internet searches,

however, turned up lots of top bar hive beekeepers with absconding

package bees. Something about the hive seems to make package bees

discontented, although there are workarounds to keep your bees in

place. Some keepers wire a few frames of wax to top bars, while

others spread wax and/or propolis along the inside walls. Others

just hunt down a nuc.

- Overheating. Mark's gut feeling is that the hive got too hot in the scorching sun. It's in the same location where our Langstroths once lived and is a paler color, so I didn't think that would be a problem, but we're going to put a thermometer inside the hive to test his hypothesis. Since poo-pooing his hypothesis, I read internet reports that overheating will cause a colony to abscond, so he may be on the right track.

- Africanized honey bees. Our packages came from Texas, and the proprietors of the apiary admit that their bees may have partial Africanized genetics. I didn't think it would be a problem since the beekeeping company has bred the meanness out of their bees, but I did read a report that Africanized honey bees are far more likely to abscond than European honey bees.

- Flight path obstructions.

I turned the top bar hive to face away from the center of our homestead

so they wouldn't be buzzing into us as we worked in the garden. A

chicken wire fence sits just a couple of feet away from their entrance,

which I wouldn't think would be a problem, but I have read that bees

prefer hives without flight path obstructions.

Other common causes of

absconding that aren't relevant to my disappearing package include:

lack of food, lack of space, and presence of parasites or

diseases. Bad odors can also drive bees away, and I did feel like

straw in my kill mulch under the hive was giving off a strong smell, so

that's a slight possibility.

If we can't find a nuc

to refill our top bar hive and have to wait for a new package next

year, I'll do things a bit differently. In addition to leaving

the bees strictly alone, I'll reduce the opening more, perhaps even

making a queen includer to fit over the entrance for the first week,

forcing the matriarch to stay put.

And three hours after

losing our colony, I realized what I really should have done --- called

in our beekeeping mentor for hands-on help. I was afraid that if

I delayed, the swarm would fly to a less accessible location, so I

muddled through trying to catch it myself and failed. But I'll

bet my mentor would have made short work of rehiving those bees.

Twenty-twenty hind-sight!

Yesterday, you learned what

a package of bees is,

so today I'm going to walk you through installing a package into a

hive. Evening is the best time to hive a package since the coming

night makes bees more likely to stay in their new home. If your

bees arrive early, put them in a room-temperature, quiet place to await

the hour before sunset. (A closet, garage, or spare room works

fine.)

Meanwhile, you should be

gathering your supplies. All you really need to hive a package is

a hive tool and a nail or piece of wire to puncture the candy in the

queen cage, but you might find some other equipment handy.

Meanwhile, you should be

gathering your supplies. All you really need to hive a package is

a hive tool and a nail or piece of wire to puncture the candy in the

queen cage, but you might find some other equipment handy.

Bees in a package are

very gentle, but they're also confused and will land all over your

head, hands, and arms. I recommend wearing a veil at the least,

and you might feel more comfortable in a full bee suit. If you're

able to allow bees to settle on your bare skin without batting at them,

this is one procedure that works much better without gloves, but go

ahead and wear hand protection if you're going to be nervous without.

Other tools you might

use include:

- Scissors (in case your queen cage is attached to a fabric strap)

- Spray bottle of sugar water (in case the bees freak you out and you need to sedate them)

- Screw and screwdriver or staple gun (in case you need to attach the queen cage to a top bar)

- Bee brush (to move

addled bees out of the way when closing the hive back up)

With

your tools assembled, take another few minutes to prepare your

hive. Each type of hive is prepped differently, and I'll cover

the specifics for Warre hives and top bar hives in later posts.

If you're installing a package into a Langstroth hive, I recommend

doing a little additional research to find out those details. At

its most basic, hive preparation consists of making a space into which

you can pour bees.

With

your tools assembled, take another few minutes to prepare your

hive. Each type of hive is prepped differently, and I'll cover

the specifics for Warre hives and top bar hives in later posts.

If you're installing a package into a Langstroth hive, I recommend

doing a little additional research to find out those details. At

its most basic, hive preparation consists of making a space into which

you can pour bees.

Now you can start to pry

your package apart. If you ordered more than one package and they

were mailed as a single unit, use your hive tool to separate the

packages. Next, pry off the cardboard or plywood cover on top of

one package, as is shown above.

Underneath the cardboard or

plywood lid, you'll see the top of the can of syrup. There will

also be a strap --- either fabric or thin metal --- that attaches to

the queen cage. It's very important that you don't knock the

queen cage off this strap and that you don't let the queen cage fall

into the package of bees. Both mistakes can be remedied, but

beginners will do better to prevent them.

Underneath the cardboard or

plywood lid, you'll see the top of the can of syrup. There will

also be a strap --- either fabric or thin metal --- that attaches to

the queen cage. It's very important that you don't knock the

queen cage off this strap and that you don't let the queen cage fall

into the package of bees. Both mistakes can be remedied, but

beginners will do better to prevent them.

If the strap is metal, you

should be able to pry it loose from its staple, but I had to cut my

fabric strap. I was careful to leave enough strap that I could

hold onto the remainder while pulling out the can of syrup.

If the strap is metal, you

should be able to pry it loose from its staple, but I had to cut my

fabric strap. I was careful to leave enough strap that I could

hold onto the remainder while pulling out the can of syrup.

You'll notice that you

really need three hands for this procedure, but you'll find a way to

make do with two. Using the hive tool, pry at the top of the can

of syrup until you can get a grip on it. Then hold onto the queen

strap with one hand while pulling out the can of syrup with the

other.

Set the can of syrup

aside while pulling out the queen cage and placing the cardboard or

plywood lid back on the package so bees don't stream out. (Yes,

some bees will escape during this procedure --- don't worry about it.)

What you should be focusing

on now is the queen cage.

If the weather is chilly, brush off attendant bees and stick the queen

cage in

your pocket until you're ready to deal with her. If it's warm,

just set her aside while you get the tools for the next part of the

procedure. But don't lose her!

What you should be focusing

on now is the queen cage.

If the weather is chilly, brush off attendant bees and stick the queen

cage in

your pocket until you're ready to deal with her. If it's warm,

just set her aside while you get the tools for the next part of the

procedure. But don't lose her!

You'll notice that the

queen cage has corks on two ends, one of which leads directly into the

queen's living area (right side of the above photo) and the other of

which goes into the candy plug (left side of the above photo).

Beginners should leave the cork on the living area side alone and

instead focus on removing the cork that leads into the candy.

You can take out the

cork with anything you want. Pros often use the corner of their

hive tool, but I found it much easier to spear the cork with a piece of

wire and pull it loose.

Underneath

the cork is a plug of candy. You want to make a hole in the candy

large enough for the queen's scent to waft through, but not so large

that the queen herself can crawl out. The queen should have to

chew for a day or two before she can escape.

Underneath

the cork is a plug of candy. You want to make a hole in the candy

large enough for the queen's scent to waft through, but not so large

that the queen herself can crawl out. The queen should have to

chew for a day or two before she can escape.

To get this effect,

pierce the candy with a nail or wire. Be careful that you don't

skewer the queen!

The candy in one of my

queen cages had partially melted (see the photo on the right).

It's not the end of the world if your hole doesn't really work --- you

can let the queen out in a few days if she hasn't escaped on her own.

Where you put the queen

depends on what kind of hive you're using. Do a little research

on your own or read my posts about top bar and Warre hive installation

(coming soon for those reading this post as I write it, or linked at

the bottom if you're reading this post later). I'm assuming

you've installed the queen before you move on to the next step below.

Now for the fun (read:

scary) part --- pouring the bees into the hive! Bees in a package

tend to cluster near the top, and you want them loose and

pourable. If you're scared of your bees, spray them with sugar

water now (but that's not really necessary --- I didn't). Next,

tap the box of bees solidly on the ground to knock them loose, take off

the lid, then quickly upend the box over top of the open hive.

Pouring worker bees out

of a package takes a bit of skill. You'll end up tilting the box

from side to side so bees drop out the entrance hole, and you'll

probably stop several times to tap the box again and knock bees

loose. This is when bees will fly all around and scare you, but

remember that hiveless bees are gentle and very unlikely to sting.

Later posts will tell you how

to close your hive and make sure your

package install was a success, but I've got a bit more advice for

the installation phase. First, don't worry about all those bees

buzzing around in the air. As soon as the workers in the hive get

their feet under them, some will go to the entrance and start fanning

air full of queen pheremone out to attract stragglers. (You can

see one bee fanning in the photo here, taken through the observation

window in our Easy Hive.)

Later posts will tell you how

to close your hive and make sure your

package install was a success, but I've got a bit more advice for

the installation phase. First, don't worry about all those bees

buzzing around in the air. As soon as the workers in the hive get

their feet under them, some will go to the entrance and start fanning

air full of queen pheremone out to attract stragglers. (You can

see one bee fanning in the photo here, taken through the observation

window in our Easy Hive.)

The bees stuck in the package

are more problematic. If you're a better thumper and shaker than

I am, you might get them all out the first time, but I find that it's

easier to wait until ten or fifteen minutes after the hive has been

closed up and everyone has settled down, then to come back and check on

the package. Chances are, you'll see bees clustering in the upper

corners, as in the photo above.

The bees stuck in the package

are more problematic. If you're a better thumper and shaker than

I am, you might get them all out the first time, but I find that it's

easier to wait until ten or fifteen minutes after the hive has been

closed up and everyone has settled down, then to come back and check on

the package. Chances are, you'll see bees clustering in the upper

corners, as in the photo above.

A couple of thumps and shakes

are all it takes to knock most of the remaining bees out onto the

ground, which will make it easier for the bees to find their way to the

hive. Place the package in front of the hive, hole-side-up, and

nearly every bee will be in the hive come morning.

A couple of thumps and shakes

are all it takes to knock most of the remaining bees out onto the

ground, which will make it easier for the bees to find their way to the

hive. Place the package in front of the hive, hole-side-up, and

nearly every bee will be in the hive come morning.

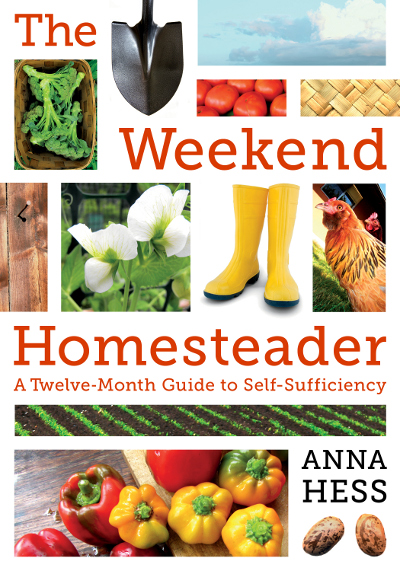

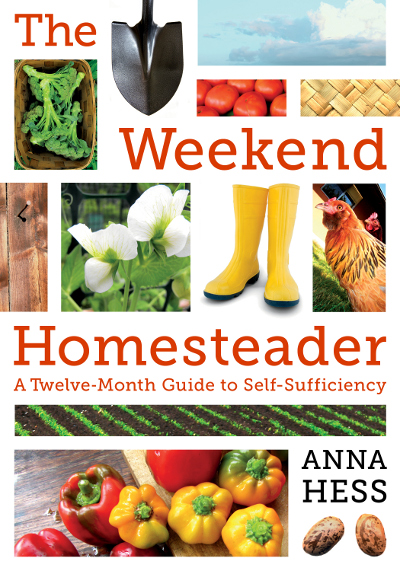

Weekend

Homesteader is full of fun and easy projects to help guide you onto

the path to self-sufficiency.

| This post is part of our Bee Package lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We've been putting off

building a porch for the back of our trailer since we moved in, which

meant we could only use that door with extreme caution.

Last fall we managed to buy

enough lumber for an 8x16 deck, but getting started proved to be a

challenge due to other pressing projects.

Today we got half way there

with the help of a carpenter named Bradley. We were so happy with his

work we decided to hire him to also do a roof for the porch. He's

charging 100 dollars for the 5 hours of labor required for the deck,

and he doesn't mind the long walk across the creek!

Looks like we're in for

a round of periodic

cicadas this

year! I was sorry to miss them in 2011, but it looks like the

17-year Brood 1 does live in our area, despite

usually being restricted to upland parts of the Blue Ridge (about 80

miles east of us). The red-eyed cicadas started popping up all

over the farm Monday, and I snagged each new arrival to

feed our chickens.

Maybe we'll eat the next ones ourselves?

(No, the cicada didn't

do that to my thumbnail. I've now learned not to roll my eyes

when Mark tells me bungee cords are dangerous. The bruise doesn't

hurt any more, but it was sore for two days and did

restrict my weeding for a whole week!)

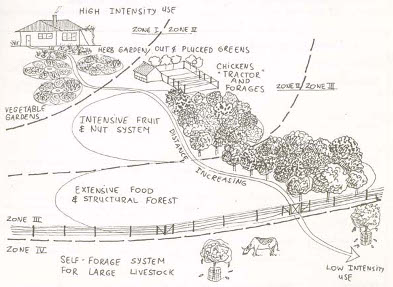

If you want to install a

package of bees into a top bar hive, I recommend that you start

by reading my general instructions for bee

package installation.

This followup posts gives the specifics for top bar hives --- how many

bars you use, where the bees go, feeding, etc. --- but assumes you

understand the basics of hiving a package.

If you're installing a

package of bees into a brand new top bar hive (like our Easy Hive),

you should start by placing ten to twelve top bars between two follower

boards in the center of the hive. Those of you who are using a

golden mean top bar hive might give the

bees only eight to ten top bars for their initial living area since the

golden mean hive is more capacious.

Alternatively, if your

entrance is at the end of the hive, you can use a single follower board

an appropriate number of top bars from the end. Either way, you

might as well install the rest of the top bars on the other side(s) of

the follower board(s), even though the bees won't be using them right

now.

Now that you've put all

of the top bars in, it's time to take some out. I removed two top

bars in the center of the bees' new living area, but wished I'd taken

out three or four to make it easy to pour bees in.

Next,

consider how you want to feed your bees. A new package will have

to be fed for some variable amount of time to get them off to a good

start. (I hope that more experienced beekeepers will leave a

comment telling me how long they feed new packages of bees since I've

seen very conflicting advice on the internet.) You can read my

post about cooking up sugar syrup here, but you still have to make

a decision on how to get that sugar to the bees.

Next,

consider how you want to feed your bees. A new package will have

to be fed for some variable amount of time to get them off to a good

start. (I hope that more experienced beekeepers will leave a

comment telling me how long they feed new packages of bees since I've

seen very conflicting advice on the internet.) You can read my

post about cooking up sugar syrup here, but you still have to make

a decision on how to get that sugar to the bees.

Most people seem to make

baggie feeders by filling a ziplock bag with sugar water, then pricking

tiny holes in one side and placing the baggie in the bottom of the top

bar hive. I don't like disposables, and I have these entrance

feeders leftover from our Langstroth hive days, so I started out by

putting an entrance feeder in the living area of the top bar

hive. I suspect I'll want to make a hole in the bottom of one of

the follower boards  soon so that bees won't build

comb around the feeder (and so I can refill it without disturbing the

girls).

soon so that bees won't build

comb around the feeder (and so I can refill it without disturbing the

girls).

Next, open up the

entrance holes leading into the new living area, and get ready to

install your package of bees! The queen cage goes between two of

top bars in the living area. You can usually just bend a metal

strip over and not worry about attachment, but my fabric strip needed a

screw to hold it in place.

If you have an

observation window, don't make the mistake I did. Face the open

side of the queen cage toward the window so you can watch her escape.

Once you install the

queen cage, push the top bars on either side back into place, leaving a

hole into which you can pour bees.

In this photo, you can

see why I recommend taking out more than two top bars to prepare for

the worker bees. I ended up dumping more bees than I wished onto

the top bars rather than into the hive cavity. This wasn't a big

deal (and would have been even less of a big deal if I'd had my bee

brush handy), but the operation will go more smoothly with a larger

opening.

Now you can replace the

top bars you removed to pour in the worker bees. I ended up

gently blowing bees out of the way since I didn't have a brush on

hand. A few bees ended up stuck on top, but I suspect they'll

escape through cracks in the cover.

Put

the lid on and you're done! Well, until you check on the bees and

take out the queen cage in a few days, which I'll explain in detail

Friday.

Put

the lid on and you're done! Well, until you check on the bees and

take out the queen cage in a few days, which I'll explain in detail

Friday.

This is my first package

install into a top bar hive, so I hope those of you who are more

experienced with the hive will weigh in. Are there any steps

you'd change in my description? Any additional tips?

Don't

know where to start with your homesteading adventure? The

Weekend Homesteader will guide you on your way.

Edited to add: After writing this

post, our bees absconded (flew away) from our top bar

hive. I don't think my installation method had

anything to do with it (see the linked post for ideas on what the

culprit was), but I can't be sure.

| This post is part of our Bee Package lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

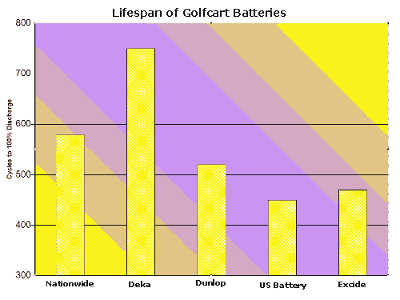

I learned two golf cart

lessons this morning.

1. You can haul more lumber

when the load is better balanced.

2. Entrance and exits are

easier when you use the front door.

Now we have enough materials

for the rest of the porch

project and a roof to go

over it.

Bradley says he's only going

to charge us $175 for all of his hard work building an 8 by 16

covered porch.

We're trying to talk him up to $200....

Bradley says he's only going

to charge us $175 for all of his hard work building an 8 by 16

covered porch.

We're trying to talk him up to $200....

Meanwhile, Mark and I

have been dropping by and watching him work as we take breaks from our

own regular tasks. If it wasn't planting month, I'd be tempted to

have us both "help" him for the whole project, because I can tell

Bradley has a lot of experience to impart despite his youth. Here

are a few pointers I've picked up already:

Building

with all new materials goes fast if you know what you're doing. It looks like it's

going to take Bradley only about nine hours to build the entire porch

with no help. I estimate that Mark and I, working together, would

have taken twice that long (which means four times the

man-hours). With scavenged materials, we'd probably multiply our

time by two again, but we would have saved a lot of cash --- we spent

$660 on materials for this project.

To

save on supplies with a metal roof, make your rafters run cross-wise. The first two photos

in this post show how Bradley made the roof rafters run the opposite

direction from what you'd expect, which saved quite a bit of wood and

was still plenty sturdy enough for him to walk on.

Use

scabs and brackets to turn a two person job into a one person job. Mark kept asking

Bradley if he needed help with daunting tasks like setting the four by

four posts upright, but Bradley had it  covered. He used wooden

scabs and brackets to hold the posts erect until he'd built a box on

top to provide structural integrity.

covered. He used wooden

scabs and brackets to hold the posts erect until he'd built a box on

top to provide structural integrity.

Plan

ahead so you don't need to double up. Although he

envisioned the 8'x16' porch as two 8'x8' squares attached to each

other, Bradley got by with one joist where the squares join by building

directly onto the side of the central four by four legs. (See

above.)

We'll share more shots

of the porch when it's done!

If you understand the basics

of bee package installation, putting a package into a Warre hive is absurdly simple.

You'll want to start with two boxes, with top bars in place in the

bottom box and absent in the top box. Set aside the cover and

quilt for now and get your package ready.

If you understand the basics

of bee package installation, putting a package into a Warre hive is absurdly simple.

You'll want to start with two boxes, with top bars in place in the

bottom box and absent in the top box. Set aside the cover and

quilt for now and get your package ready.

After prepping your

queen cage, simply lay it flat on the top bars of the bottom box.

You don't want to set the queen cage on the bottom of the entire hive

because she'll need bees to cluster around her for warmth during the

first couple of nights before she chews her way free, and the bees will

prefer to hang out above the ground.

Now pour the worker bees

into the empty top box. This procedure becomes much more complex

if you made your Warre hive

in the traditional manner, with fixed frames. In that case, you

either

have to pour bees into an inverted top box and flip it into place, or

run

the bees up a  white sheet or towel into the

box. Luckily, Mark

installed pins in my Warre hive so I can move the frames as

needed.

I'll still keep my hands off as much as possible to maintain

the integrity of the hive.

white sheet or towel into the

box. Luckily, Mark

installed pins in my Warre hive so I can move the frames as

needed.

I'll still keep my hands off as much as possible to maintain

the integrity of the hive.

With the queen and

workers in place, you can replace the bars in the upper box. This

would be a good time to have a bee brush on hand, but it also works to

just lower top bars slowly enough that bees can escape out from under

them.

Blowing is another

method of getting bees out of your way as you place the burlap inner

cover, then the quilt

box on top of the hive.

We filled our quilt box with

straw, but you can use any insulative material. (It's best to do

that before the bees are buzzing around your head.) The roof

slides right down over top of the quilt, sealing the insulative

material in with an inner mouse board, but allowing air to flow under

the eaves.

We filled our quilt box with

straw, but you can use any insulative material. (It's best to do

that before the bees are buzzing around your head.) The roof

slides right down over top of the quilt, sealing the insulative

material in with an inner mouse board, but allowing air to flow under

the eaves.

The entrance feeder for

my Langstroth hive fit into the mouth of the Warre hive once I put a

cinderblock underneath to support it. This narrows the entrance

quite a bit, so I'll probably find another place for the feeder once

the bees are really up and running, but it'll be good enough for now.

Stay tuned for tomorrow's

post, which covers removing the queen cage and making sure the first

combs are being built straight.

Stay tuned for tomorrow's

post, which covers removing the queen cage and making sure the first

combs are being built straight.

Meanwhile,

don't forget to preorder

a copy of my paperback, chock full of projects to make your

homesteading adventure a success.

| This post is part of our Bee Package lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Warre hive

vertical top bars need a pin to keep them secure.

I didn't have any nails that

size, so we made our own pins by cutting small sections of 14

gauge galvanized wire and hammering them into pilot holes.

Pay extra attention to the

space between the bars. It might help to mark all the holes before you

actually drill.

The saying that you

spend 90% of your time carrying out 10% of the tasks in an average job

is true in the garden too. Taking a few minutes to root out

inefficiencies really pays off, even though it seems hard to budget the

hours when putting in your spring garden.

This year, we've been

focusing on making it easier to mow

the garden aisles. Clumps of tall

fescue, like the one

I'm digging out in the top photos, bog down the mower and take several

extra seconds (and quite a bit of brute force) to trim down. It

doesn't sound like much, but once you've hit ten clumps of fescue, the

time (and hassle) adds up. We're slowly but surely rooting out

these problem grasses, leaving the more well-behaved bluegrass

and white clover to

take their place.

Meanwhile, I'm also slowly

fixing the crazy quilt of a front garden, parts of which I hand-dug

during our first couple of years on the farm. At the time, I'd

never worked in a garden with permanent beds, so I assumed lots of

cross aisles would make my job easier. The truth is, I almost

never walk down those cross aisles, and it's very tough to maneuver the

mower around to cut the grass in them. (It would be a bit easier

if my aisles were wider like in the mule garden.)

Meanwhile, I'm also slowly

fixing the crazy quilt of a front garden, parts of which I hand-dug

during our first couple of years on the farm. At the time, I'd

never worked in a garden with permanent beds, so I assumed lots of

cross aisles would make my job easier. The truth is, I almost

never walk down those cross aisles, and it's very tough to maneuver the

mower around to cut the grass in them. (It would be a bit easier

if my aisles were wider like in the mule garden.)

So I'm spending a few

extra minutes to lay down a kill mulch and turn the cross-aisles into

part of long, linear beds. This year, I'll just let the grass die

back under the cardboard, then this fall I'll plant an oat cover crop

to start building the soil up in these new garden spots. I  figure by next year, I'll be

able to plant vegetables, increasing my growing area while also making

the garden easier to maintain.

figure by next year, I'll be

able to plant vegetables, increasing my growing area while also making

the garden easier to maintain.

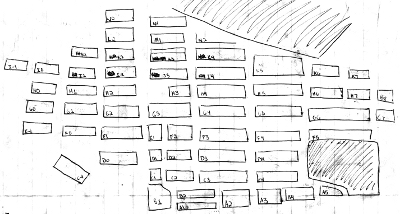

The only slight

disadvantage of my bed merger is that now I'm going to have to add

decimals to my numbering scheme. It already has negative numbers

--- how geeky can you get?

Weekend

Homesteader: May contains a whole chapter on tricks for planning an

ergonomic garden. The chapter has been expanded and moved to

April in my new

paperback.

After installing

a package of bees

into your new hive, you can sit back and relax...for a couple of

days. Most beekeepers recommend that you reopen the hive after

two to three days to make sure the queen has escaped from her cage,

removing the cork from the non-candy end and letting her run out if

not. I've usually had to help the queen escape, so you probably

will too --- just work over the hive and be extra careful that the

queen doesn't fly away or fall into the grass. After she's been

released, take the queen cage away with you rather than leaving it in

the hive (where bees will build funny comb

After installing

a package of bees

into your new hive, you can sit back and relax...for a couple of

days. Most beekeepers recommend that you reopen the hive after

two to three days to make sure the queen has escaped from her cage,

removing the cork from the non-candy end and letting her run out if

not. I've usually had to help the queen escape, so you probably

will too --- just work over the hive and be extra careful that the

queen doesn't fly away or fall into the grass. After she's been

released, take the queen cage away with you rather than leaving it in

the hive (where bees will build funny comb  off it) or around the hive

(where the queen pheremones still on the cage could make your workers

think she's leaving the hive).

off it) or around the hive

(where the queen pheremones still on the cage could make your workers

think she's leaving the hive).

As one of our readers

wrote, the other important followup task is to feed, feed, feed.

Even if you're trying to keep bees as naturally as possible, a new

package is the one instance where you really do need to feed your bees

since they require that sustenance to draw out comb and nurture

babies. I

asked readers for advice on what to feed our bees, and the best answer I got

was that it's safest to simply feed a new package sugar

water --- only give  honey

to bees from the same colony that made that honey (which you clearly

can't do with a package). As for how long to feed, it sounds like

the colony will need 6 to 8 weeks to get new workers flying around and

searching for nectar, so you may want to continue to feed your bees for

that long. Other people stop feeding as soon as the bees

start to producing capped frames of honey.

honey

to bees from the same colony that made that honey (which you clearly

can't do with a package). As for how long to feed, it sounds like

the colony will need 6 to 8 weeks to get new workers flying around and

searching for nectar, so you may want to continue to feed your bees for

that long. Other people stop feeding as soon as the bees

start to producing capped frames of honey.

Finally, if you're using

foundationless frames (nearly always in a top bar or Warre hive and sometimes also in a

Langstroth hive), it's important to make sure those first combs are

built straight. Bees line up future combs of wax parallel to the

first one they build, so if that one is crooked, your whole hive will

be full of crooked comb. Beekeepers will either cut out a bad

piece of wax or correct its orientation to get the bees off to a good

start.

Now you're ready for the

really hard part --- leaving your bees alone! We'll see how long

I can go before the urge to look into my Warre hive becomes unbearable.

Don't

miss my

paperback, full of

48 fun and easy projects to help you embark on your homesteading

journey without becoming overwhelmed.

| This post is part of our Bee Package lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

The folks at wireless deer fence.com

asked us if we would give their battery operated deer deterrent a try

and we said sure.

It runs on 2 AA batteries and

comes with a pack of scented sections of rubber hose that fits on top

of the blue center piece.

I pointed the trail camera

towards the area, and maybe if were lucky we might catch some of the

electric excitement. Their website mentions how they'll pay for video

footage of the wireless deer fence in action. You get 3 stakes, plus

the attractant for 60 dollars and that includes shipping. It comes with

a 2 year unconditional guarantee. We just put them in today, so stay

tuned for a full report on how we think it works at keeping those

garden nibblers away from our vegetables.

This has been a strange year

since we've had cash to pay experts to make some capital improvements

on the farm.

This has been a strange year

since we've had cash to pay experts to make some capital improvements

on the farm.

The barn

roof repair job was

definitely worth every penny, but it's only the beginning of a long

project of barn reorganization.

The porch, on the other

hand, is pure luxury.

Dining out in the open

air on a hot summer afternoon feels just as luxurious as sitting in

front of the wood

stove does in the

winter.

Both the wood stove and

the porch cut back on our electric bill, but they're really all about

enjoying life. You can tell an improvement is decadent when

Huckleberry moves right in.

Some friends of ours found a

free green house on Craigs list and asked us if we wanted the wooden

plant tables.

"Heck yeah!" was my response.

We've already got a short

list of possible project ideas, with aquaponics near the top. Thank you Frankie, Jim, and Dudley

for the delivery and helping with unloading.

I easily gathered eight cicadas while going about my morning

chores on Thursday, and I popped them all into the freezer so they

would perish quickly and then be ready for a lunch taste test.

You can eat cicadas raw, but I needed all the help I could get to

overcome the "I'm eating a bug" factor, so I sauteed them in a bit of

vegetable oil, salt, and pepper for about ten minutes until the

exoskeletons were pretty crunchy. Then I served the wildcrafted

treat up, four cicadas per plate.

I easily gathered eight cicadas while going about my morning

chores on Thursday, and I popped them all into the freezer so they

would perish quickly and then be ready for a lunch taste test.

You can eat cicadas raw, but I needed all the help I could get to

overcome the "I'm eating a bug" factor, so I sauteed them in a bit of

vegetable oil, salt, and pepper for about ten minutes until the

exoskeletons were pretty crunchy. Then I served the wildcrafted

treat up, four cicadas per plate.

I couldn't talk Mark

into eating a single one --- he said he might try a cicada another time

if I removed the wings. Adding the insects to a stir fry (and not

telling the recipients)  might be another good way of

tricking non-believers into taste-testing cicadas. And, to be

honest, I had to look in the other direction while popping the bits of

invertebrate flesh into my mouth, a bit like what I do when I get a

shot. (If I can't see it, the scary thing isn't there and I can

focus on my real senses.)

might be another good way of

tricking non-believers into taste-testing cicadas. And, to be

honest, I had to look in the other direction while popping the bits of

invertebrate flesh into my mouth, a bit like what I do when I get a

shot. (If I can't see it, the scary thing isn't there and I can

focus on my real senses.)

So, what do cicadas

taste like? Actually, when I could ignore the fact that I was

eating an insect, they were delicious. Keep in mind that I

taste-tested what's known in culinary circles as "soft-shelled cicadas"

--- youngsters who have just popped out of their nymphal skins and

haven't yet hardened up their exoskeletons.

I didn't detect the

almond or pistachio flavor reported on the internet. Instead, the

texture (and flavor, actually) was like the flesh from the one lobster

tail I've tasted, but without that faint hint of fishiness, and with a

little crunch when my teeth hit the wings. (I really liked the

cicadas wings-on and don't recommend removing the appendages.)

Since there are several species of periodic cicadas, I wouldn't be at

all surprised if each one tastes a little different.

On a scale of 1 to 10, I'd

give these sauteed cicadas a 9. In addition to tasting good, the

insects also really agreed with me --- as I started writing this post,

my mouth watered and I snuck one of the cicadas I'm saving into my

mouth for a snack. On the other hand, it probably would have

taken all day to gather enough cicadas to serve as the protein source

for a whole meal, so I'll just keep snagging the delicacies as I pass

them by.

On a scale of 1 to 10, I'd

give these sauteed cicadas a 9. In addition to tasting good, the

insects also really agreed with me --- as I started writing this post,

my mouth watered and I snuck one of the cicadas I'm saving into my

mouth for a snack. On the other hand, it probably would have

taken all day to gather enough cicadas to serve as the protein source

for a whole meal, so I'll just keep snagging the delicacies as I pass

them by.

Which is all a long way

of saying --- I recommend them! If you've got cicadas crawling up

out of the ground, now's a perfect time to see if you like them as much

as I do.

The easy way to catch a chicken is to wait till it gets dark and pick

them up off their roost.

We each got spelunking head

lamps back when our power went out

for 2 weeks, and quickly discovered how awesome a head mounted

light source can be.

My advice is to pay a little

extra for the higher end model that allows you to adjust the angle

where the light shines.

I thoroughly enjoyed

everyone's thoughts on chapter

1 of Walden, even

though I didn't comment much, so I hope you all had time to read

chapter 2 --- "Where I lived, and what I lived for". I'm going to

write about two themes that caught my eye in this chapter, but, as

usual, feel free to comment on whatever you found the most interesting

instead.

I thoroughly enjoyed

everyone's thoughts on chapter

1 of Walden, even

though I didn't comment much, so I hope you all had time to read

chapter 2 --- "Where I lived, and what I lived for". I'm going to

write about two themes that caught my eye in this chapter, but, as

usual, feel free to comment on whatever you found the most interesting

instead.

Buying land

What struck me first is

how similar the beginnings of my and Thoreau's journeys were...and how

different the endings. "At a certain season of our life, we are

accustomed to consider every spot as the possible site of a house,"

Thoreau wrote, and went on to tell about all of the properties he

toured, one of which he came within a hair's breadth of buying.

I also went through a

land-yearning stage in which I drew maps of how I'd turn real and

hypothetical properties into vibrant homesteads, and I ended up happily

married to our plot of land. On the other hand, Thoreau decided

that the wiser course is to love and leave the land. "As long as

possible live free and uncommitted," he advises us. "It makes but

little difference whether you are committed to a farm or to the county

jail." Similarly, in the first chapter, he wrote about "young

men, my townsmen, whose misfortune it is to have inherited farms,

houses, barns, cattle, and farming tools; for these are more easily

acquired than got rid of."

This reminds me of Mike's

comment on my

previous Walden post in which he reminds us that no one can be free of

the economy, even if you buy a plot of land outright, grow your own

food, and need nothing else. Thoreau was thinking

more of the upkeep of a farm than he was about property taxes and a

mortgage, but both points have merit. So, my first discussion

question is --- do you think voluntary simplicity can be achieved if

you own land?

The news

The second thing that struck

me in this chapter was more of a side note than a theme. Mark and

I have come to belief this over the last few years, but have had a hard

time articulating the premise, so I'll let Thoreau do it for me:

The second thing that struck

me in this chapter was more of a side note than a theme. Mark and

I have come to belief this over the last few years, but have had a hard

time articulating the premise, so I'll let Thoreau do it for me:

I've had several people

tell me that that it's somehow ethically imperative to stay up to date

on the world's news, but I've come to consider it all a

distraction. Yes, I do my homework and figure out the issues when

the time comes to vote, but I don't see any point in being emotionally

involved in the day to day running of the world if I can't do anything

about it. Which brings me to my second discussion question --- do

you consider all news gossip, or do you think we're morally obligated

to stay up to date on current events?

Chapters 3 and 4

Unless I hear that it's

a hardship for anyone, let's plan to talk about "Reading" and "Sounds"

next Monday. Now I'm looking forward to hearing what you have to

say about chapter 2!

(As a side note, I might

not be able to pull your comments out of moderation until this evening,

so don't despair if they don't show up as quickly as usual. I

promise I'm not weeding out comments I don't like --- everyone except

clear spam always makes it through moderation.)

My

new paperback includes fun and easy projects for every weekend of

the year to help guide you onto the path to self-sufficiency.

Our chicken

pasture/moat perimeter is coming close to completion.

Sometimes I like to recruit a

tree to function as a fence post, like this small walnut.

It saves time and money, but

it also looks more natural, which in my opinion increases the already

high level of beauty around here.

We left our beloved porch Sunday and Monday to see my

favorite little sister graduate from Berea College.

Congratulations, Maggie!

I

call the photo above "Three Mothers". We were waiting for the

first appearance of our graduate....

I

call the photo above "Three Mothers". We were waiting for the

first appearance of our graduate....

Here she comes!

The photo below depicts

Mom's first sighting.

Walking across the

stage....

Her rooters below.

Then cookies and punch

in the quadrangle.

My favorite grand-nephew

seemed more interested in the brownies than in the dry-roasted cicadas I brought just for him.

What are kids coming to these days?

We're so proud of you,

Maggie!

Cornish

Cross broilers are usually eaten at 8 weeks. We give our

heirlooms an extra month

since they grow slower, but the deadline is still fast approaching.

We killed the rooster

last week and have four of last year's broilers left in the

freezer. Looks like we'll be eating a lot of chicken dinners in

May.

John

Little is a regular reader who lives in Japan and shared the following

fascinating data about differences between colony collapse disorder

there and in the U.S. I'll let him tell you the story in his own

words.

On a different subject, bees

and CCD [colony

collapse disorder],

I recently came across some local (Japanese) information which seems,

on the face of it, to confirm the neonicotenoid connection. At an

apple growers meeting a couple of weeks back, one of the members

brought along a pre-release version of a documentary on DVD called "A

message from the bees".

On a different subject, bees

and CCD [colony

collapse disorder],

I recently came across some local (Japanese) information which seems,

on the face of it, to confirm the neonicotenoid connection. At an

apple growers meeting a couple of weeks back, one of the members

brought along a pre-release version of a documentary on DVD called "A

message from the bees".

Basically, there were

two critical points which differentiate the experience of

CCD here in Japan from

what is generally being seen in Europe and the U.S. The first is

that beekeepers here are

seeing different symptoms. Instead of empty hives, they're

finding piles of dead and incapacitated bees on the bottom boards and

in front of the hives. In the majority of cases, the deaths have

been correlated to local spraying of neonicotenoid-based insecticides

60 days before.

The second piece of

interesting information is that the spray dosage levels in Japan are

much, much higher than

in most of the rest of the world. For the common insecticides

used by fruit growers, the allowable levels (in ppm) are 20 to 300

(yes, three hundred!) times those mandated in Europe or the U.S.,

leading researchers here to the conclusion that they have identified a

"smoking gun".

As one old beekeeper

from the coast of Nagasaki-ken (in southern Japan) put it, "The centre

of Tokyo is now the safest place to raise bees. The air there is

cleaner than any part of the Japanese countryside".

Scary information

(especially for those of us who are involved in agriculture). And

the "message" from the bees? "You're not just killing us (bees),

you're killing

yourselves, too".

We decided to consult our new

porch

builder for some advice on shoring up the water damage in the barn.

He's had some experience with

barns like this and made short work of securing the above 4x4 with a

couple well placed 2x6 scabs.

Phillip Meeks, an extension agent in

southeast Kentucky who works with a number of beekeepers, emailed me to

share his experiences with packages

of bees. He

wrote:

Phillip Meeks, an extension agent in

southeast Kentucky who works with a number of beekeepers, emailed me to

share his experiences with packages

of bees. He

wrote:

Because of this, I've begun to steer my own beekeepers away from the packaged swarms, trying to persuade them towards nucs instead. They're a bit more costly, but I've had great luck with the last one I bought, as have many of my beekeepers.

I don't know WHY the performance of packages has gone downhill, but it seems to be a consistent issue.

Anyway, just wanted to toss in my two cents -- not that it's any help to you now. I hope you can at least take it as encouragement that [your absconded package] probably isn't beekeeper error!

I'd be curious to hear

from those of you who have had packages abscond. Has the

experience only begun in the last few years, or did you see the

behavior previously?

Turns out some of the structural

damage to our barn was due to poison ivy vines.

The vines were exposed to

falling water, which got conducted to various spots for what I'm

guessing is decades.

It wasn't a problem for our

new hired hand. He's been immune to the effects of poison ivy since he

was a kid.

I like to save

seeds from my own tomatoes, but last year I got the

idea that perhaps saving seeds is one of the reasons blight always shows up in my

plantings. I think it's more likely that tomato blights simply

thrive during our warm, humid summers, but I figured it wouldn't hurt

to experiment by buying tomato seeds for 2012.

Now I wish I

hadn't. I'm struggling to fill my tomato beds with romas this

year, despite planting two flats and a quick hoop full. Before I

complain about the seeds, though, I have to be fair and say that part

of the problem was my own fault.

I put tomato seeds in

the quick hoops too early since it was so warm in March, and they came

up just before a serious cold spell. The quick hoops weren't

enough to repel frost when the outside temperature dropped into the

teens, so the tomato seedlings got nipped. I replanted the garden

beds in early April, but by then it had gotten so hot that the soil was

bone dry. In retrospect, I should have waited to plant my tomato

seeds in the quick hoops until April 1 no matter what the weather was

doing, and I should have taken the covers off on a warm day to let the

sprinklers hydrate the ground and get the tomatoes up and growing.

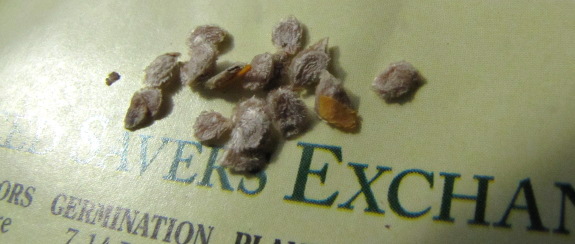

Good

thing I decided to hedge my bets by starting some seedlings inside,

right? Unfortunately, this is where problematic seeds came into

play. I figured stock from Seed Savers Exchange would be as good

or better than any seeds I could save on my own, but now I'm not so

sure. The seeds in one packet looked dusty gray when they

arrived, almost as if the seeds were covered in mold, and I had a lot

of germination issues that got worse with each planting (suggesting

that the seeds were already near the end of their energy reserves when

they reached our farm). My second flat showed only 25% healthy

seedlings, and many of the plants came up headless, with cotyledons

seemingly pinched off by a hard seed coat. (This is very

different from damping off, which would have showed up as the stem

withering at the base.)

Good

thing I decided to hedge my bets by starting some seedlings inside,

right? Unfortunately, this is where problematic seeds came into

play. I figured stock from Seed Savers Exchange would be as good

or better than any seeds I could save on my own, but now I'm not so

sure. The seeds in one packet looked dusty gray when they

arrived, almost as if the seeds were covered in mold, and I had a lot

of germination issues that got worse with each planting (suggesting

that the seeds were already near the end of their energy reserves when

they reached our farm). My second flat showed only 25% healthy

seedlings, and many of the plants came up headless, with cotyledons

seemingly pinched off by a hard seed coat. (This is very

different from damping off, which would have showed up as the stem

withering at the base.)

Steve

Solomon wrote that most seeds sold to home gardeners are of poor quality, but that we blame

ourselves for seeds that don't sprout. I can see his point --- I

can't be confident this year's tomato dilemma is due to bad seeds and

not to some issue on my end. Regardless, I won't be planting as

many tomatoes as I'd hoped (although still more than last year), and

there will be more slicers and tommy-toes than usual since they

sprouted better than the romas.

That said, it's hard to

complain when the first few survivors are already nearly at the bloom

stage. And maybe at least the blight situation will be better

this year?

Edited

to add: See this

followup post which

probably exonerates Seed Savers Exchange.

The plan is to mount our solar

cell panels on the top

and build drying racks for curing garlic and sweet potatoes towards the

middle area.

"Scythes are cool!" our

readers

admonish us every time we talk about our weedeater.

I used to be in love with the idea of scything once upon a time...and

then I was given a scythe.

"Scythes are cool!" our

readers

admonish us every time we talk about our weedeater.

I used to be in love with the idea of scything once upon a time...and

then I was given a scythe.

At the time, I didn't

know much about the tool, so I wasn't wise enough

to turn down the bulky American scythe and to save my pennies for a

quality Austrian scythe instead. I also trusted my father when he

told me that one size scythe fits all. That may be true if you're

a normal-sized man, but as a short woman, I spent all of my energy just

trying to keep the scythe blade from digging into the earth. I

gave up on the tool in disgust.

But then I stumbled

across Harvey

Ussery's scything page,

and was tempted once more. Ussery

explained that Austrian scythes cut with blades curved in three

dimensions, so they glide over the surface of the ground. In

contrast to the traditional American scythe blade --- which is stamped

out by a drop-forge press and has to be heavy to keep from breaking ---

Austrian blades are hand-forged by a blacksmith, so they are sharp,

light, and dent rather than shatter if you hit a rock. In fact, The

Scythe Book explains

that "over half the [Austrian scythe] blades

which begin the twenty-six stages of manufacture are rejected along the

way", which is why the blades are of such high quality (and cost so

much).

Then there's the handle,

known as a "snath" in scything circles.

Austrian snaths are typically very light, and both types of snath can

be fitted to your unique body. If you're an absolutely raw

beginner like me, you can order a scythe from The Scythe Supply

that's suited exactly to your proportions since you give them your

height, your handedness, the number of inches from ground to hip, and

your cubit (the distance from your elbow to your out-stretched middle

finger). The company will be sure the handles go in the right

places so you're not straining anything as you mow.

While you're making your

decision, you'll also need to choose a kind and length of blade.

Your main choices are between bush/brush blades, which are short and

thick so they won't break when you whack at young saplings, and grass

blades, which are lighter and won't wear you out when you're cutting

softer plants. (A ditch blade is a bit of a hybrid, halfway

between the graceful grass blade and the hefty bush blade.) Grass

blades can be long or short, with longer blades being handy for

harvesting vast fields of wheat and shorter blades being more useful

when mowing small lawns with lots of edges. I think the raw

beginner could do worse than picking a middle of the road grass blade

--- I chose the 24 inch grass blade pictured here.

While you're making your

decision, you'll also need to choose a kind and length of blade.

Your main choices are between bush/brush blades, which are short and

thick so they won't break when you whack at young saplings, and grass

blades, which are lighter and won't wear you out when you're cutting

softer plants. (A ditch blade is a bit of a hybrid, halfway

between the graceful grass blade and the hefty bush blade.) Grass

blades can be long or short, with longer blades being handy for

harvesting vast fields of wheat and shorter blades being more useful

when mowing small lawns with lots of edges. I think the raw

beginner could do worse than picking a middle of the road grass blade

--- I chose the 24 inch grass blade pictured here.

With all of that in mind, I begged Mark to let me splurge on a hunk of

wood and metal, and he did. I'm here to tell you that the

difference between an American scythe that doesn't fit an an Austrian

scythe that does fit is like night and day. But this post is

already too long, so you'll have to wait to hear more about what

scything feels like and how to maintain a quality scythe blade in later

posts. If you want to learn more now, I highly recommend this

video my mom tracked down, which somehow manages to be inspiring and

hilarious all in a two minute time frame.

Golf cart jousting is a

modern twist on a 15th century popular past time that replaces the

horse with a golf cart and the traditional lance with a couple of 4x4's

bungee strapped together.

Once

you start playing with cover crops, bare soil jumps right out

at you and begs to be planted. Last fall, we tore

a bit more of the old house down, exposing a big patch of

earth in which all plant life had been shaded out. It was too

late to plant anything else, so I just scattered a bunch of rye seeds

on the ground and proceeded to ignore it.

Once

you start playing with cover crops, bare soil jumps right out

at you and begs to be planted. Last fall, we tore

a bit more of the old house down, exposing a big patch of

earth in which all plant life had been shaded out. It was too

late to plant anything else, so I just scattered a bunch of rye seeds

on the ground and proceeded to ignore it.

The rye sprouted and

turned into a lawn-like coating before winter hit. Then, this

spring, the grain shot up and started to bloom.

If I was ready to use

that plot of earth, I'd cut the rye now and let the straw fall as

mulch. But there are still huge floor joists to be moved before

the footprint of the old house can be turned into garden, and we have

no time for projects like that at this time of year.

So I'm allowing the rye

go to seed to give me some more time before I need to make a decision

about that bit of earth. Truly a do-nothing

grain patch, I

haven't tilled, fertilized, or done anything else to the rye.

We'll probably feed any grain we get to the chickens, but what I'm

really salivating over is the hefty stalks for mulch.

Recently we gave a neighbor a

bag of extra lettuce and he turned around the next day and gave us a

bag of fresh trout.

Anna is not a lover of

seafood like myself, but she didn't hesitate to clean up these three

trout for dinner the other day so I could have a treat.

It was delicious. Makes me

wonder if raising trout in an aquaponic

setting might be possible for

us.

A few weeks ago, Everett asked us what we do during

our weekends

of non-work. I

always look a little shame-faced when people inquire about our leisure

hours because the cultural norm is to fill that time with activities

outside the home --- hiking, going to a movie, or whatever.

A few weeks ago, Everett asked us what we do during

our weekends

of non-work. I

always look a little shame-faced when people inquire about our leisure

hours because the cultural norm is to fill that time with activities

outside the home --- hiking, going to a movie, or whatever.

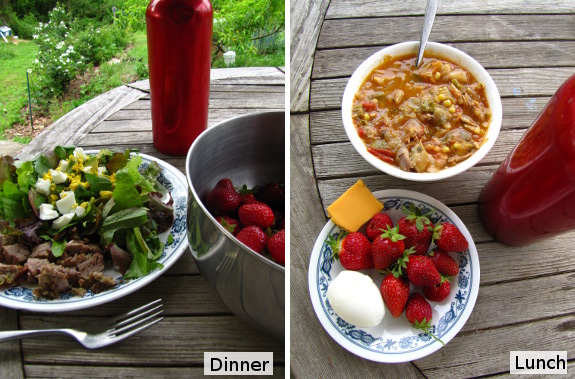

In contrast, a blissful

day off in Anna-land starts with gathering a big jar of cicadas

for the tweens, then

morphs into a quiet morning reading on the porch while listening to a catbird

singing from the walnut or watching the three week old chicks learning

to forage in the lawn. I'll probably spend a little extra time

making something fancy for lunch, then will gravitate from non-fiction

to novel-reading in the afternoon. If I'm feeling crazy, I might

have my mother over for tea. I'm simply a boring person.

Which is all a long way

of saying that chapter 4 of Walden really spoke to me.

Thoreau wrote:

I think that one of the major

benefits of living in paradise is that you don't feel the need to spend

much money on expensive leisure pursuits. As Joe Dominguez and

Vicki Robin wrote in Your

Money or Your Life,

the goal of voluntary simplicity is to turn your life into a vacation

so you don't need to take a vacation way from home. It has taken

several years for Mark to bring me around to this way of life, but I'm

now eternally grateful that he invented weekends.

I think that one of the major

benefits of living in paradise is that you don't feel the need to spend

much money on expensive leisure pursuits. As Joe Dominguez and

Vicki Robin wrote in Your

Money or Your Life,

the goal of voluntary simplicity is to turn your life into a vacation

so you don't need to take a vacation way from home. It has taken

several years for Mark to bring me around to this way of life, but I'm

now eternally grateful that he invented weekends.

That said, Walden's chapter 3 went right over

my head, and also made me wonder if my rants against TV sounded like Walden's rants

against easy reading. In this day and age, most people think

they're feeding their minds if they crack open a bit of chick lit or

flick on the History Channel, let alone "read Homer or Aeschylus in the

Greek".

So, what did you think of

this week's installment of Walden? Unless I hear some

"no!"s, I'll plan on us all reading chapters 5 and 6 (Solitude and

Visitors) for next Monday. If you're new to the book

club, you might want

to check out the thought-provoking comments on chapter

1 and chapter

2 as well. I

appreciate you all giving me the impetus to spend some time thinking

about this classic!

So, what did you think of

this week's installment of Walden? Unless I hear some

"no!"s, I'll plan on us all reading chapters 5 and 6 (Solitude and

Visitors) for next Monday. If you're new to the book

club, you might want

to check out the thought-provoking comments on chapter

1 and chapter

2 as well. I

appreciate you all giving me the impetus to spend some time thinking

about this classic!

Want

more reading material? You can peruse my revised rant against

television in The

Weekend Homesteader.

We started out with one of

these bags leftover from Anna's

year abroad with a Watson fellowship.

Now we've got 6 of the same

oversized bags.

They mainly get used to carry

out boxed up chicken waterers, but have several other uses including leaf

gathering.

I was going to title this

post "Fruitless" and talk about how Blackberry

Winter wiped out all of the tiny fruits on the peaches, apples,

pears, cherries, gooseberries, and plums. The tale wasn't going

to be all doom and gloom since blueberries, raspberries, grapes,

strawberries, and blackberries either missed the frost or bloomed over

a long enough time frame that we should enjoy quite a lot of fruit this

summer. And yet, even that isn't the full picture.

I was going to title this

post "Fruitless" and talk about how Blackberry

Winter wiped out all of the tiny fruits on the peaches, apples,

pears, cherries, gooseberries, and plums. The tale wasn't going

to be all doom and gloom since blueberries, raspberries, grapes,

strawberries, and blackberries either missed the frost or bloomed over

a long enough time frame that we should enjoy quite a lot of fruit this

summer. And yet, even that isn't the full picture.

The truth is that I tend

to go in the opposite direction of most folks, telling you about all of

our failures but only focussing on the biggest successes. There

are simply so many garden achievements every year, you'd be bored stiff

if I regaled you with the first snap peas (Sunday), the first real meal

of non-frost-nipped strawberries (last week), and so on ad infinitum.

It occured to me that you

can't walk around our garden --- prettier this year than ever before

--- and see it for yourselves. So here it is in all of its mid

May glory!

It occured to me that you

can't walk around our garden --- prettier this year than ever before

--- and see it for yourselves. So here it is in all of its mid

May glory!

The photo above was

taken in our front garden, the oldest vegetable patch on our farm,

where the soil is the best, the sun the worst, and the aisles

in need of streamlining. I set out most of our

garlic there last fall, along with a bed of Egyptian onions, some chives, and our experimental potato

onions, so the area

feels like one big mass of Amaryllidaceae.

onions, so the area

feels like one big mass of Amaryllidaceae.

The empty beds are

filling up fast with summer crops, many of which have already popped

up. Once we put in our second planting of things like green

beans, corn, and squash this week, the front garden will be pretty much

full.

The back garden (shown

below) is nearly all coated with annual

ryegrass in an

attempt to repair the waterlogged, topsoil-less ground. Mark's

been doing a great job of mowing the  garden beds each time he cuts

the aisles, which maximizes the grass's growth and means lots more

organic matter works its way into the soil. That one bare bed is

coated with tiny basil seedlings, and you'll notice I snuck

strawberries into the back garden despite this being its fallow year.

garden beds each time he cuts

the aisles, which maximizes the grass's growth and means lots more

organic matter works its way into the soil. That one bare bed is

coated with tiny basil seedlings, and you'll notice I snuck

strawberries into the back garden despite this being its fallow year.

Meanwhile, the chick

brooder is hidden behind our second oldest peach tree. Even

though we won't be enjoying luscious peaches this year, at least the

tree provides some much-needed shade.

And, at the bottom of

the back garden, our Chicago

hardy fig only died

partway back this past winter. I pruned the bush to three stems,

cut off the dead tops, and am hoping to taste figs for the first time

this fall!

Moving on, I forgot to

take a picture from afar of the forest garden, home to this year's

tomatoes, but the photo below pretty much sums it up.

And then there's the mule

garden, from whence most of our meals are coming at the moment.

I've been putting all of my energy into getting the front garden ready

for summer crops lately, so the mule garden is looking a little ragged

around the edges, but not so much that the crops are suffering.

This week, I'll be starting my next pass through, taking down the last

quick hoops, weeding the seedlings who were too small to work around a

month ago, and adding more mulch.

And then there's the mule

garden, from whence most of our meals are coming at the moment.

I've been putting all of my energy into getting the front garden ready

for summer crops lately, so the mule garden is looking a little ragged

around the edges, but not so much that the crops are suffering.

This week, I'll be starting my next pass through, taking down the last

quick hoops, weeding the seedlings who were too small to work around a

month ago, and adding more mulch.

I'm already thinking

ahead to fall since this sunny garden is the best spot for

overwintering greens. Soon, I'll plan where all the late summer

and autumn crops will go, and will probably set aside a lot of the mule

garden beds to be planted in wave

after wave of buckwheat. That will prevent me

from sneaking summer crops into areas slated for the fall garden, and

will build organic matter at the same time.

Another alternative is

to let some of the spring crops go to seed. Every year, I add one

or two more vegetables to my list of easy to save seeds, and the new

experiments this year are kale and Swiss chard (the latter

of which is shown below on the left.)

I hope you enjoyed your

garden tour! If you were here in person, you would be snacking on

a sugar snap pea and a juicy strawberry by now, but hopefully you'll

get the gist photographically. 2012 is far from fruitless!

Garlic will be the first test curing, but that's still weeks away.

I didn't contact Seed Savers

Exchange about my potentially

bad tomato seeds

because I wasn't 100% sure the problem was their fault. But one

of their employee's --- Tom Wahlberg --- stumbled across my post and

emailed me in concern. He told me that, "like we state on each

packet, we really do mean Satisfaction Guaranteed, and have credited

your account for these two packets."

I didn't contact Seed Savers

Exchange about my potentially

bad tomato seeds

because I wasn't 100% sure the problem was their fault. But one

of their employee's --- Tom Wahlberg --- stumbled across my post and

emailed me in concern. He told me that, "like we state on each

packet, we really do mean Satisfaction Guaranteed, and have credited

your account for these two packets."

While the refund was

appreciated, I was more intrigued to hear about how Seed Savers

Exchange grows, processes, and tests seeds. Wahlberg explained:

Depending on the length of time

of fermentation it is possible the Organic would have a higher level of

fungal activity, but also would retain more of the normal fuzzy

exterior which could also be what you are seeing. The

Conventional by contrast will have been processed via acid extraction,

which is not a seed treatment, but rather a method commercial growers use to break down the

gelatinous membrane around the seed without the delay inherent with the

fermentation process. That would also explain the difference in

the shade between the two varieties.

Depending on the length of time

of fermentation it is possible the Organic would have a higher level of

fungal activity, but also would retain more of the normal fuzzy

exterior which could also be what you are seeing. The

Conventional by contrast will have been processed via acid extraction,

which is not a seed treatment, but rather a method commercial growers use to break down the

gelatinous membrane around the seed without the delay inherent with the

fermentation process. That would also explain the difference in

the shade between the two varieties.As for germination, we utilize Midwest Seed Services for independent analysis, and the most recent results are as follows:

| Variety |

Date of test |

Germination |

Lot# |

| Amish Paste --- Conventional |

01/12 |

96% |

107-1824 |

| Amish Paste --- Conventional |

02/12 |

98% |

107-1911 |

| Martino's Roma --- Organic |

11/11 |

96% | OG259-381 |

Wahlberg went on to

tell me that Seed Savers Exchange has started hundreds of Amish Paste

plants in the greenhouse this year (some of which you can see in this

and the previous photo). "In light of your observations, we will

also start a flat of the Martino's for evaluation."

Wahlberg went on to

tell me that Seed Savers Exchange has started hundreds of Amish Paste

plants in the greenhouse this year (some of which you can see in this

and the previous photo). "In light of your observations, we will

also start a flat of the Martino's for evaluation."He finished by telling me:

I thought I should set the record straight, and will let you know what Wahlberg finds out about the Martino's Roma seeds.

So I was on my way to get

some horse manure this morning when the truck all of a sudden stopped

and wouldn't start back up.

The local dealer was just a

short hike down the road...Gulp.

It was only 50 dollars to

have them go back and fetch our truck with the above bigger truck. They

won't look at it till tomorrow.

Dealerships have always made

me nervous. I think I might rather walk down a dangerous dark alley,

but sometimes they're the best mechanical choice. I'll spare you the

wallet munching stories that have helped me to form this opinion. So

far today's experience is working out to change my mind at least a bit.

This dealer is in Castlewood...city for us, but most people

would consider it a country dealership, which feels like an advantage.

Maybe that's why the people working there seem so much friendlier than

the last dealer I was at?

Even though staking up plants

seems absurdly simple, we've gone through a lot of trial and error

before finding techniques that work for us. But first --- why tie

up plants at all?

Even though staking up plants

seems absurdly simple, we've gone through a lot of trial and error

before finding techniques that work for us. But first --- why tie

up plants at all?

We stake plants in our

vegetable garden for their own good and to make our lives easier.

Staking tomatoes (combined with pruning) keeps the leaves drier,

which holds off blight in hot, humid climates like ours. After

you stop picking your asparagus, the tall fronds can easily become top

heavy and snap off during windy or wet weather, and I've found the same

is true of plants like kale when you let them fruit in order to collect

the seeds. Then there's the fact that it's annoying to have to

lift up those tall plants sprawling across the aisle every time you

want to push a wheelbarrow or mower through.

We've tried lots of different