archives for 04/2012

The

peach

flowers are mostly

done. A few are still pretty and pink like the one shown above,

but most are starting to "undress", with dried up petals slipping off

of fuzzy young fruits.

The

peach

flowers are mostly

done. A few are still pretty and pink like the one shown above,

but most are starting to "undress", with dried up petals slipping off

of fuzzy young fruits.

If you can see the

ovaries left behind when the petals drop away, you know the tree has

decided to mature the fruit. Even if you can't quite make out of

the ovary, it's a good sign if you notice "dead" flowers clinging to

your fruit tree twigs after the petals are gone. Of course, late

freezes, self-thinning, and all kinds of other

things could result in a fruitless year even if you see ovaries at this

stage, but we can always dream.

Our plum tree did drop all of its flowers,

as I suspected it might since this was its first bloom year, but the nanking

cherry bushes seem to be keeping theirs. So do the lower

limbs of the pear trees, despite my topworking.

Our plum tree did drop all of its flowers,

as I suspected it might since this was its first bloom year, but the nanking

cherry bushes seem to be keeping theirs. So do the lower

limbs of the pear trees, despite my topworking.

Still lots of floral

excitement left to come in our perennial plantings this spring.

Our  Virginia Beauty apple opened

up a few flowers this week, and several clusters are still in the bud

stage. Meanwhile, one of our gooseberries is also well laden.

Virginia Beauty apple opened

up a few flowers this week, and several clusters are still in the bud

stage. Meanwhile, one of our gooseberries is also well laden.

Next up, blueberries!

One problem I noticed when

using 14 gauge electric

fence wire as a diagonal support is the difficulty in backing off

the tension if you tightened it too much.

The first alternative I

thought about was nylon rope, but I'm guessing the galvanized wire

would win that longevity race.

Maybe I'll use nylon rope on

the next gate so we can get a side by side comparison.

Last week, I mentioned that our

pear flowers were mostly being overlooked by pollinating bees, with all

of the buzz centering around the peaches instead. Since then, the peach

flowers began to decline and the pears opened more fully, which did

attract a few more bees to the pear blooms. But beetles were

still the primary pear pollinators.

Last week, I mentioned that our

pear flowers were mostly being overlooked by pollinating bees, with all

of the buzz centering around the peaches instead. Since then, the peach

flowers began to decline and the pears opened more fully, which did

attract a few more bees to the pear blooms. But beetles were

still the primary pear pollinators.

As with most of ecology,

the story is complex. It turns out that nectar has varying sugar

concentrations depending on the plant species, with one source listing

the following averages:

- Apple - 46.2%

- Peach - 28.9%

Plum - 25.8%

Plum - 25.8%- Sour cherry - 23.5%

- Pear - 9% (with other sources listing 4% to 25%)

Of course, sugar

concentrations vary by variety as well, and are also affected by

weather. Low humidity leads to more sugar in nectar while high

humidity waters down the kool-aid.

But all else being

equal, you can see why a bee might prefer a peach flower to a pear

flower (and why lack of pollination is a problem in many pear

orchards). That said, pear flowers produce large quantities of

pollen, so honeybees rearing brood might spend time on there.

Beetles don't seem to

mind the lower sugar content of the pear blooms, perhaps because most beetles visit flowers primarily for pollen. Whatever the reason, I continued to see lots of

different kinds of beetles on my pear flowers, along with the holey

petals and leaves  that are the by-product of

these "mess and soil pollinators".

that are the by-product of

these "mess and soil pollinators".

Bugguide.net users

tentatively identified the beetles in my second photo as Hoplia (usually considered a pest

since it eats rose blossoms, but seemingly doing pollinating work here)

and those in the third as Paria. I didn't try to ask

for an ID on this last beetle because I couldn't zoom far enough in.

As a side note, I was

interested to read that fire blight bacteria are hindered by high sugar

concentrations in nectar, which is probably why pears are the most

frequent victims of the illness. Perhaps pear varieties resistant

to fire blight have sugar concentrations greater than the threshold 20

to 30%?

The

vote was tied, so I

decided to write both Permaculture Chicken and Garden Ecology at the

same time, splitting the books up into bite-size segments and churning

them out in whatever order suits my fancy. The topic I was most

excited to write about first was incubation...which may be why this

ebook kept expanding until it was twice the size of my Weekend

Homesteader ebooks. Who knew there was so much to write about

cute chicks?

The

vote was tied, so I

decided to write both Permaculture Chicken and Garden Ecology at the

same time, splitting the books up into bite-size segments and churning

them out in whatever order suits my fancy. The topic I was most

excited to write about first was incubation...which may be why this

ebook kept expanding until it was twice the size of my Weekend

Homesteader ebooks. Who knew there was so much to write about

cute chicks?

Permaculture

Chicken: Incubation Handbook is now available for 99

cents from Amazon's Kindle store. If you have Amazon Prime, you

can also borrow the book for free. No matter how you read it, many

thanks in advance if you can find the

time to write a brief review. I don't know if you realize

it, but it's your reviews and early purchases that have helped my

ebooks reach thousands of new eyes.

Stay tuned at noon all

week as I hit the book's highlights as this week's lunchtime

series. But there is way too much in my Incubation Handbook to

fit into a few short posts, so I hope you'll give the whole thing a

read, if only to enjoy the 90 plus photos and the chapter on pasturing

young chicks.

This post is part of our Chicken Incubation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Chicken Incubation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I posted

yesterday about the

possibility of using nylon rope instead of 14 gauge electric fence wire

on our next gate.

Turns out that was a creepy

suggestion that should be avoided for this particular application.

The main reason I was

considering nylon was because we have a massive spool of it. (Thanks

Mom)

A timely comment from Roland

was what set me straight. The nylon rope would more than likely stretch

over time due to the constant stress of the turnbuckle. The material

science term for this influence is known as creep. A word that creeped

its way into the music industry not once but three times in recent

history thanks to bands like Radiohead, TLC, and Stone Temple Pilots.

We're nearly at the end of last fall's

carrots. I

thought there were so many, but we've been enjoying eating them with hummus this winter, as well as in

the usual cooked dishes. Good thing spring carrots are already in

the ground to replace them.

We're nearly at the end of last fall's

carrots. I

thought there were so many, but we've been enjoying eating them with hummus this winter, as well as in

the usual cooked dishes. Good thing spring carrots are already in

the ground to replace them.

I saved back the carrots

that still look plump for raw eating, but decided all the

less-then-perfect carrots at the bottom of the crisper drawer needed to

go into a soup. We bought another pastured

lamb recently and

asked the butcher not to discard the bones, so we had just what we

needed to make high  quality

broth. That rich liquid, plus the meat picked off the bones, a

heaping handful of shriveled carrots, several fresh Egyptian onions, and a bit of thyme blended

into a delicious spring soup.

quality

broth. That rich liquid, plus the meat picked off the bones, a

heaping handful of shriveled carrots, several fresh Egyptian onions, and a bit of thyme blended

into a delicious spring soup.

If you're interested in

my theory behind in-season soup-making, check out this

post, or the longer

version in Weekend

Homesteader: July.

Soup is one of the easiest things to cook without a recipe!

While

we'd love our favorite hens to stick around forever, chickens

have a limited shelf life. A hen begins to lay when she's about

six months old, and she does her best work by the time she's a year

and a half old. Depending on how hard-nosed you are, you might

keep your laying hens one year, two years, or three years, but after

that, you're feeding large amounts of grain to an animal who has

basically become a pet.

While

we'd love our favorite hens to stick around forever, chickens

have a limited shelf life. A hen begins to lay when she's about

six months old, and she does her best work by the time she's a year

and a half old. Depending on how hard-nosed you are, you might

keep your laying hens one year, two years, or three years, but after

that, you're feeding large amounts of grain to an animal who has

basically become a pet.

If you want to replace

those old hens who are no longer laying

enough

to pay for their feed, you've got several options. You might be

able to find someone local who is selling point-of-lay hens (pullets

just beginning to churn out eggs). More likely, you'll order

chicks from a hatchery. Or, if you're willing to put in a little

extra effort, you can incubate your own chicks from homegrown eggs.

Raising new members of your

flock at home has several

advantages, the first of which is that you can incubate as few or as

many eggs as you want. In

contrast, hatchery raised chicks usually require a minimum order of 25

birds to ensure that the

youngsters produce enough body heat to survive two or three days in

a mail truck. Backyard chicken keepers will be hard pressed to

find room for such a large flock.

Raising new members of your

flock at home has several

advantages, the first of which is that you can incubate as few or as

many eggs as you want. In

contrast, hatchery raised chicks usually require a minimum order of 25

birds to ensure that the

youngsters produce enough body heat to survive two or three days in

a mail truck. Backyard chicken keepers will be hard pressed to

find room for such a large flock.

Even more important from

a permaculture point of view is the ability of

the incubating homesteader to tweak the genetics of her flock.

Hatcheries that sell to the general public focus first on breeding

birds well

suited to surviving in a hatchery setting, often aiming for

appearance as

the second priority. If you want to breed a bird that's able to

hunt for its own food, you'll be much happier if you can select your

best birds and raise their young to become your next generation.

As a final point in favor of

incubating your own chicks, you're the

one in

control of the process from start to finish. You don't risk

diseases from the hatchery or from someone else's farm coming along for

the ride. Your chickens don't have to deal with the trauma of

being shut up in a box or cage for an hour or two days as they make

their way to your farm. And you can start chicks at whatever time

of

the year matches your schedule. Plus, you get to enjoy the

Lifetime Channel version of Chicken TV --- the miracle of new chicks

pushing their way out of their shells.

As a final point in favor of

incubating your own chicks, you're the

one in

control of the process from start to finish. You don't risk

diseases from the hatchery or from someone else's farm coming along for

the ride. Your chickens don't have to deal with the trauma of

being shut up in a box or cage for an hour or two days as they make

their way to your farm. And you can start chicks at whatever time

of

the year matches your schedule. Plus, you get to enjoy the

Lifetime Channel version of Chicken TV --- the miracle of new chicks

pushing their way out of their shells.

This

week's lunchtime series is excerpted from Permaculture

Chicken: Incubation Handbook. I hope you'll splurge 99 cents

to read the whole thing!

This post is part of our Chicken Incubation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Chicken Incubation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We recently upgraded our chicken waterer labels from

black and white to color and the first shipment arrived today.

We're both thrilled with how

vibrant the colors turned out.

Feels kind of nice to

immortalize a member of our original flock this way.

I've

been dipping back into Edible

Forest Gardens recently because when I first read the two volume

set, it was like drinking from a firehose --- a lot of the best

information went right past me. On further perusal, a throwaway

line in appendix 5 caught my interest: Garter snakes are "not as

beneficial to gardens as believed".

I've

been dipping back into Edible

Forest Gardens recently because when I first read the two volume

set, it was like drinking from a firehose --- a lot of the best

information went right past me. On further perusal, a throwaway

line in appendix 5 caught my interest: Garter snakes are "not as

beneficial to gardens as believed".

The authors didn't

provide any extra information, so I've been turning

the phrase over and over in my head ever since. Jacke and

Toensmeier did mention that earthworms make up 80% of a garter snake's

diet, so maybe the dislike is due to garter snakes eating beneficial  invertebrates?

If that's the case,

though, surely they would have said the same thing about worm snakes.

invertebrates?

If that's the case,

though, surely they would have said the same thing about worm snakes.

Since a garter snake

model kindly posed for my photo shoot Monday, I

thought I'd toss the question out at our readers. Why do you

think garter snakes are "not as beneficial to gardens as believed"?

If

you want a perfect hatch, you need to start with perfect eggs.

Factors that influence an egg's hatchability include whether the egg

was fertilized, whether the shell is in good shape, and how the egg was

stored. Below, I've included the section on seasons and parentage

from Permaculture

Chicken: Incubation Handbook --- be sure to check out the

book to learn more about selecting eggs with a good shape and shell

quality, how to store eggs before they go in the incubator, and what to

expect with mail order eggs.

If

you want a perfect hatch, you need to start with perfect eggs.

Factors that influence an egg's hatchability include whether the egg

was fertilized, whether the shell is in good shape, and how the egg was

stored. Below, I've included the section on seasons and parentage

from Permaculture

Chicken: Incubation Handbook --- be sure to check out the

book to learn more about selecting eggs with a good shape and shell

quality, how to store eggs before they go in the incubator, and what to

expect with mail order eggs.

Time of year deserves

consideration as you plan your hatch.

I

prefer to

incubate chicks in February and March so they're out on pasture during

the peak grass-growing season of March through June, then I start

another batch in late summer to take advantage of the secondary pasture

peak in September through November. If you're revitalizing your

laying flock, it's important

to have chicks out of the shell by

early to mid April to ensure they are old enough to lay before days

shorten in the fall. Otherwise, you'll be feeding non-laying

pullets all winter.

laying flock, it's important

to have chicks out of the shell by

early to mid April to ensure they are old enough to lay before days

shorten in the fall. Otherwise, you'll be feeding non-laying

pullets all winter.

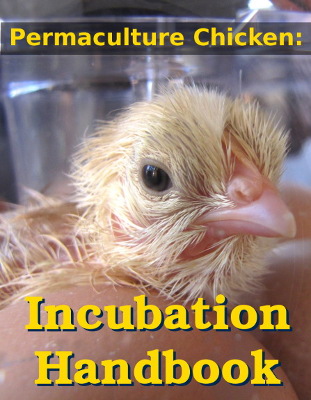

However, chicken biology

dictates a slightly different hatch pattern. As you can see in

this chart, eggs tend to be most fertile in March through June,

with a secondary peak in fertility in September and October.

Don't feel obliged to follow the chart's lead, but do be aware that

your results won't be quite as good if you're trying to raise chicks in

the dead of winter.

A related issue is the

health of the eggs' parents. Older poultry

manuals admonish you to keep your breeding stock out on lush pasture,

since the high nutrition forage results in eggs that are more likely

to hatch. In my own experience, I've found that breeds of

chickens that produce brighter yolked eggs (meaning that the hens ate

more bugs and greenery) have higher hatch rates.

While we're on the topic of

parents, feed isn't the only important

factor. Hens and roosters who have just become sexually active or

who are more than two years old will produce fewer fertile

eggs. I once tried to hatch eggs from four year old hens and

had abysmal results, convincing me that even if these hens are still

laying, most of the embryos aren't viable enough to mature.

While we're on the topic of

parents, feed isn't the only important

factor. Hens and roosters who have just become sexually active or

who are more than two years old will produce fewer fertile

eggs. I once tried to hatch eggs from four year old hens and

had abysmal results, convincing me that even if these hens are still

laying, most of the embryos aren't viable enough to mature.

Of course, you must have

a rooster if you want chicks (even though a

hen will lay unfertilized eggs when no males are around). Some

chicken keepers report issues with their roosters not mating frequently

enough to ensure that all eggs are fertilized, but I've never had that

problem. On the other hand, I keep fewer hens than the

recommended dozen per rooster, so my flock's patriarch doesn't have to

work too hard to do his job.

Inbreeding is a more

tricky issue for the backyard chicken

keeper. You may need to trade roosters with like-minded friends

every year, or buy a round of straight run chicks to

raise a new rooster annually, ensuring that your hens aren't

mating with their brothers or fathers. Inbreeding tends to lead

to lower hatch rates and to a higher proportion of sick chicks out of

the

eggs that do hatch.

This post is part of our Chicken Incubation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Chicken Incubation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Its been almost a year since I

started using the new chainsaw

protective carrying bag,

and I'm ready to report that it's definitely worth 20 dollars.

The zipper is less than

perfect, but not really needed as long as you don't hold your bag in an

upside down fashion.

I like the feeling of having

all my chainsaw gear in one place, and it's nice to just grab the bag

and know you've got most of your safety gear ready to go. Which reminds

me that I need to get around to ordering a pair of chainsaw chaps.

We started planting Illinois

Everbearing Mulberries

in our chicken

pastures a couple of

years ago as future chicken feed. Despite a lot of neglect, one

of the trees from 2011 looks like it's going to make a few fruits this

year.

We started planting Illinois

Everbearing Mulberries

in our chicken

pastures a couple of

years ago as future chicken feed. Despite a lot of neglect, one

of the trees from 2011 looks like it's going to make a few fruits this

year.

Lee Reich likes to say that the

mulberry genus name Morus refers to the plant's

tendency to flower late so it's seldom nipped by frost. Since my

grasp of Latin is nonexistant, I'm going

to assume he's right. But is the beginning of April actually

late? Or is my mulberry tree more closely related to the Greek

definition of Morus --- "idiot"?

After choosing

your eggs, it's time

to start

incubating. The instructions that came with your machine will

help

you set the temperature to 99.5 degrees for a forced air model or 102

degrees for a still air model, at which point it's a good idea to let

the incubator run empty for a day while you monitor the temperature and

humidity and ensure it's working properly. If there's any chance

someone in your houshold will accidentally unplug the incubator in the

next three weeks, tape the cord into the electric socket as

insurance. (Yes, I

learned this the hard way.)

After choosing

your eggs, it's time

to start

incubating. The instructions that came with your machine will

help

you set the temperature to 99.5 degrees for a forced air model or 102

degrees for a still air model, at which point it's a good idea to let

the incubator run empty for a day while you monitor the temperature and

humidity and ensure it's working properly. If there's any chance

someone in your houshold will accidentally unplug the incubator in the

next three weeks, tape the cord into the electric socket as

insurance. (Yes, I

learned this the hard way.)

The main choice you have to make at the beginning of the incubation

process is how to arrange the eggs --- vertically like they'd sit in an

egg carton or horizontally the way they'd lie in a hen's nest.

Although the latter option sounds more natural, in practice I've had

slightly better results with vertical incubation. As the embryo

grows, the highest point in the shell becomes an air pocket which

the  chick will poke its beak into

shortly before hatching. If

this air pocket develops at the pointy end of the egg, the chick will

find it difficult or impossible to hatch without help. Setting

the eggs vertically with the blunt end up helps ensure that the chick

will be situated the right way inside the shell.

chick will poke its beak into

shortly before hatching. If

this air pocket develops at the pointy end of the egg, the chick will

find it difficult or impossible to hatch without help. Setting

the eggs vertically with the blunt end up helps ensure that the chick

will be situated the right way inside the shell.

If your incubator only

allows you to lay your eggs horizontally, I wouldn't worry too much

about it. That said, some incubationists set their eggs

inside an egg carton with the top cut off to allow them to incubate

vertically even in a simple incubator. More complicated

incubators, like the Brinsea

Octagon 20 I

recommend, often have

removable dividers that let you choose how to align your eggs.

No matter how you arrange

them, you don't want your eggs shifting

and hitting each other. Egg turners that hold individual eggs

make this point moot, but I find it helpful to add a piece of crumpled

up paper in small gaps between less solidly touching eggs in our

Brinsea Octagon 20

incubator. This ensures that I have room to lay all of the eggs

flat on the tray during the hatch, but that the eggs don't roll against

each other and risk cracking as the turning cradle rotates the

incubator.

No matter how you arrange

them, you don't want your eggs shifting

and hitting each other. Egg turners that hold individual eggs

make this point moot, but I find it helpful to add a piece of crumpled

up paper in small gaps between less solidly touching eggs in our

Brinsea Octagon 20

incubator. This ensures that I have room to lay all of the eggs

flat on the tray during the hatch, but that the eggs don't roll against

each other and risk cracking as the turning cradle rotates the

incubator.

The

decisions you make during the early incubation period have a strong

effect on how many healthy chicks eventually pop out of their

shells. Permaculture

Chicken: Incubation Handbook covers deciding whether to candle,

tips on turning the eggs,

ways to keep the internal humidity at the proper level, and what to do

if the power goes out. Check out the 99 cent ebook and become a

real incubation expert!

This post is part of our Chicken Incubation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Chicken Incubation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Dave V commented yesterday on

how he was thinking of getting a plastic hard case to carry his

chainsaw around in and if I thought there might be some advantages to

this over my fabric

chainsaw carrying bag.

First off let me be clear

that the bag I got is not an official Stihl product although the color

combination is a good imitation.

I think the biggest advantage

to a hard case is the added protection. If you carry your saw in the

back of a truck it might be wise to use a plastic case, but I rarely

take ours off the farm.

If I'd been watching the

weather with my usual eagle eye, I wouldn't have set out two-thirds of

our broccoli seedlings this week. But I was too intent on looking

at the rain percentages and hoping we wouldn't wash away in recent

thunderstorms to notice the forecast lows. (I only left the

wheelbarrow out overnight to get the photo above!)

If I'd been watching the

weather with my usual eagle eye, I wouldn't have set out two-thirds of

our broccoli seedlings this week. But I was too intent on looking

at the rain percentages and hoping we wouldn't wash away in recent

thunderstorms to notice the forecast lows. (I only left the

wheelbarrow out overnight to get the photo above!)

Which is all a long way

of saying that frost is on the forecast for tonight and again for early

next week. So I'll be repeating my quick

and dirty frost protection, trying to ensure that cold

temperatures won't harm fruit plants that are even further advanced

than last time. Here's hoping we'll see just as little damage.

The most exciting part of the incubation

process can also be the most

traumatic if you don't know what you're doing. This final post in

the lunchtime series

tells you what to expect during hatch time, but the

99 cent ebook from which the post is drawn covers much more

information. I hope you'll splurge a buck if you want to learn

more about preparing for the hatch, helping chicks out of the shell,

troubleshooting incubation problems, and getting your youngsters off to

a healthy start.

The most exciting part of the incubation

process can also be the most

traumatic if you don't know what you're doing. This final post in

the lunchtime series

tells you what to expect during hatch time, but the

99 cent ebook from which the post is drawn covers much more

information. I hope you'll splurge a buck if you want to learn

more about preparing for the hatch, helping chicks out of the shell,

troubleshooting incubation problems, and getting your youngsters off to

a healthy start.

You'll probably see at least

one chick pipping (pecking the initial

hole into its shell) on day 19 or 20. I like to record the date

and time each egg pips to give me an

indication of whether chicks are having trouble. I explain how

and when to help chicks in another section, but for now, just be aware

that it's very normal to see a delay of 8 to 12 hours between pipping

and unzipping (when the chick severs the blunt end of the shell and

breaks its way free). But if a chick has pipped but not begun to

unzip 24 hours later, it might be in trouble.

You'll probably see at least

one chick pipping (pecking the initial

hole into its shell) on day 19 or 20. I like to record the date

and time each egg pips to give me an

indication of whether chicks are having trouble. I explain how

and when to help chicks in another section, but for now, just be aware

that it's very normal to see a delay of 8 to 12 hours between pipping

and unzipping (when the chick severs the blunt end of the shell and

breaks its way free). But if a chick has pipped but not begun to

unzip 24 hours later, it might be in trouble.

If you've done a good job

with all of the early incubation steps, your

chicks will probably pop right out of their shells one after another

with no help from you. Some manuals recommend leaving your chicks

in the incubator for an entire day without lifting the lid to allow the

youngsters to

dry off completely, but I've had much better luck plucking chicks out

of the incubator within 45 minutes of hatching and either plopping them

into the brooder to finish drying off or placing them in a smaller

incubator.

If you've done a good job

with all of the early incubation steps, your

chicks will probably pop right out of their shells one after another

with no help from you. Some manuals recommend leaving your chicks

in the incubator for an entire day without lifting the lid to allow the

youngsters to

dry off completely, but I've had much better luck plucking chicks out

of the incubator within 45 minutes of hatching and either plopping them

into the brooder to finish drying off or placing them in a smaller

incubator.

The trouble with leaving

chicks in the incubator after they hatch is

that the baby birds will stumble around madly, rolling eggs and (in the

worst case scenario) spearing partially hatched chicks with their

claws. In my experience, newly hatched chicks are upset by not

having

anything soft to snuggle into, so they keep hopping around even though

they're exhausted. Once I pop a newly hatched chick under our

brooder, it stops peeping shrilly and soon falls

asleep.

The trouble with leaving

chicks in the incubator after they hatch is

that the baby birds will stumble around madly, rolling eggs and (in the

worst case scenario) spearing partially hatched chicks with their

claws. In my experience, newly hatched chicks are upset by not

having

anything soft to snuggle into, so they keep hopping around even though

they're exhausted. Once I pop a newly hatched chick under our

brooder, it stops peeping shrilly and soon falls

asleep.

There are two downsides to

removing chicks from the incubator one at a

time throughout the hatch process. Chicks

come out of the shell soaked to the skin and can easily catch a chill,

especially if you're hatching in cold weather. Forty-five minutes

in the incubator is just long enough that the chick's feathers are

(mostly) dry, but is not long enough that they puff up into the

protective

ball of fuzz most of us think of when we envision a chick. In

warm weather (and even in cold weather if there are at least two or

three other chicks in the brooder for the newly hatched youngster to

snuggle into), this level of dry off is enough. However, if your

first chick comes out of the shell when your room temperature is below

about 50 degrees Fahrenheit, you should either put up with the

problems caused by leaving the chick in the main incubator until at

least one

more chick hatches and dries, or should place the newly hatched chick

in a

spare incubator for a few hours. You'll be able to tell if you

put a too-wet chick into a too-cold brooder because it will keep

chirping frantically rather than quieting down after a minute or two.

There are two downsides to

removing chicks from the incubator one at a

time throughout the hatch process. Chicks

come out of the shell soaked to the skin and can easily catch a chill,

especially if you're hatching in cold weather. Forty-five minutes

in the incubator is just long enough that the chick's feathers are

(mostly) dry, but is not long enough that they puff up into the

protective

ball of fuzz most of us think of when we envision a chick. In

warm weather (and even in cold weather if there are at least two or

three other chicks in the brooder for the newly hatched youngster to

snuggle into), this level of dry off is enough. However, if your

first chick comes out of the shell when your room temperature is below

about 50 degrees Fahrenheit, you should either put up with the

problems caused by leaving the chick in the main incubator until at

least one

more chick hatches and dries, or should place the newly hatched chick

in a

spare incubator for a few hours. You'll be able to tell if you

put a too-wet chick into a too-cold brooder because it will keep

chirping frantically rather than quieting down after a minute or two.

The other issue with

removing chicks from the incubator one by one is

that every time you lift the lid, the incubator cools slightly and the

humidity levels drop. You can counteract this problem to some

extent with speed --- open the lid with one hand while you snag the

chick with the

other. If it's pretty cold in the room, I like to heat up some

water until it's steaming and top off the wells when I take off the

incubator lid since the hot water will keep the temperature in the

incubator high and will also increase the humidity drastically.

Using an evaporating cloth (explained in another section) also helps

keep the humidity within the incubator at a high level.

The other issue with

removing chicks from the incubator one by one is

that every time you lift the lid, the incubator cools slightly and the

humidity levels drop. You can counteract this problem to some

extent with speed --- open the lid with one hand while you snag the

chick with the

other. If it's pretty cold in the room, I like to heat up some

water until it's steaming and top off the wells when I take off the

incubator lid since the hot water will keep the temperature in the

incubator high and will also increase the humidity drastically.

Using an evaporating cloth (explained in another section) also helps

keep the humidity within the incubator at a high level.

Even

though it's not 100% necessary, I open the lid a second time after

the new chick is safely ensconced in the brooder, this time to tidy up

the interior of the incubator. I remove large pieces of eggshell

so chicks won't cut themselves on the sharp edges and I roll any

disturbed eggs over so their pipping holes are facing up.

(Sometimes, a chick will stumble across a neighboring egg and turn that

chick face down, which makes it harder for the down-turned chick to

hatch.)

Finally, I quickly move eggs around so that ones likely to

hatch soonest have a little more open space around their blunt

ends. As with removing the chick, I work quickly to ensure I

don't lower the temperature and humidity in the incubator enough that

it doesn't rebound a few minutes after I close the lid.

Even

though it's not 100% necessary, I open the lid a second time after

the new chick is safely ensconced in the brooder, this time to tidy up

the interior of the incubator. I remove large pieces of eggshell

so chicks won't cut themselves on the sharp edges and I roll any

disturbed eggs over so their pipping holes are facing up.

(Sometimes, a chick will stumble across a neighboring egg and turn that

chick face down, which makes it harder for the down-turned chick to

hatch.)

Finally, I quickly move eggs around so that ones likely to

hatch soonest have a little more open space around their blunt

ends. As with removing the chick, I work quickly to ensure I

don't lower the temperature and humidity in the incubator enough that

it doesn't rebound a few minutes after I close the lid.

This post is part of our Chicken Incubation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Chicken Incubation lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It works good as the new

nest area, and it seems

that our hens like it, but I think she's lost that broody feeling.

I've been trying to think of

methods to stimulate broody behavior. The first one is to record the

sound of a broody hen and play it back for one of her sisters while

she's comfortably tucked into her nest.

Not sure if it would work,

but it would be nice to shift some of the chick rearing workload

towards our feathered friends.

Mark's been cutting out

stumps off and on all winter to make our yard easier to mow. I

come along behind him and gather up the rotting wood (some of it nearly

stump

dirt) to add to my hugelkultur

donuts around fruit

trees in the waterlogged forest garden.

In general, the smaller

stumps rot faster, just as you'd expect. In fact, I've pulled

several four inch in diameter stumps out of the ground by myself after

wiggling them like loose teeth for a few seconds. But this week's

stumps didn't follow the trend.

The biggest stump was

well rotted despite being nearly three feet in diameter. When

Mark's saw made it all the way through, I could tell that the tree

(probably a black walnut) had grown quickly in its then-pasture

location, creating growth rings about an inch in diameter.

Perhaps the fast growth contributed to fast decay?

In contrast, the

littlest stump had barely decomposed at all. We both knew why as

soon as the saw bit into the wood --- the odor of red

cedar quickly filled

the air. I wonder how long that red cedar stump will sit in the

ground before it disappears?

The barn

roof repair project got

wrapped up yesterday!

We couldn't be happier...giddy is a more

accurate description of the feeling I get when I walk by and look up at

a fully intact roof.

We couldn't be happier...giddy is a more

accurate description of the feeling I get when I walk by and look up at

a fully intact roof.

It went so well we decided to

hire the same guy to install a gutter on one side. The other side

drains downhill towards the creek.

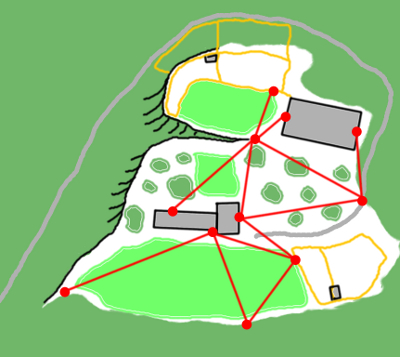

As

I wrote last year, April

is weeding month on our farm. My graph below shows

how many beds need to be planted between February and October --- April

is clearly the calm before the storm, a chance to clean up

early-planted beds (or overwinterers, like this garlic) and get a head

start on the May rush.

As

I wrote last year, April

is weeding month on our farm. My graph below shows

how many beds need to be planted between February and October --- April

is clearly the calm before the storm, a chance to clean up

early-planted beds (or overwinterers, like this garlic) and get a head

start on the May rush.

Even though I started

weeding in earnest around the end of March, I already feel a bit

behind. The crazy spring heat made everything grow much faster

than normal, so the early spring beds all need to be weeded and mulched

ASAP.

I

don't thin much, but there is a little of that on the April agenda

too. I managed to overseed the breadseed

poppies (despite cutting back my seeding rates from last year) and

Swiss chard always needs to be played with since more than one plant

germinates from each "seed".

I

don't thin much, but there is a little of that on the April agenda

too. I managed to overseed the breadseed

poppies (despite cutting back my seeding rates from last year) and

Swiss chard always needs to be played with since more than one plant

germinates from each "seed".

On the plus side, my

strawberries and garlic are in much better shape than they were last

spring --- a heavy fall mulch did its job. After a fiddly hour of

weeding around tiny seedlings, I like to give myself a break by ripping

out the few chickweed and dead nettle plants that came up in a garlic

bed. So satisfying to weed a whole bed in under a minute!

Maybe that's what all of my weeding jobs will be like in a decade when

my soil is rich, my mulch deep, and the weed seeds few.

Our new Stihl MS

211 chainsaw is about to turn a year old.

The smaller size really comes

in handy for stump removal, and the newer engine has about half as much

exhaust fumes to breath in.

I've had a few instances where I

felt like it was underpowered, but that was more the fault of a dull

chain, and I had a small learning curve with the starting procedure. It

took me a while to figure out when you push the choke all the way down

it sometimes springs back up if you're not paying attention.

I've had a few instances where I

felt like it was underpowered, but that was more the fault of a dull

chain, and I had a small learning curve with the starting procedure. It

took me a while to figure out when you push the choke all the way down

it sometimes springs back up if you're not paying attention.

Are you struggling with a

thorny garden problem and can't figure out why your cucumbers keep

dying or what that pesky weed is in your pasture? Maybe you're

more interested in breaking free of your job and need some tips to turn

your microbusiness idea into a reality. Or perhaps you've just

moved to your dream homestead and are trying to decide where to put the

chicken coop and which of those sticks in the yard are fruit trees and

bushes.

Are you struggling with a

thorny garden problem and can't figure out why your cucumbers keep

dying or what that pesky weed is in your pasture? Maybe you're

more interested in breaking free of your job and need some tips to turn

your microbusiness idea into a reality. Or perhaps you've just

moved to your dream homestead and are trying to decide where to put the

chicken coop and which of those sticks in the yard are fruit trees and

bushes.

We're here to

help! One lucky reader will win a free consultation to smooth

their path to homesteading independence. Two hours of email

answers from me and Mark can save you weeks (maybe even years) of trial

and error, and we promise you'll get your money's worth. Use it

up all at once, or have Walden Effect as your on-call mentor all summer.

What do you have to do to

enter our giveaway? The paperback

edition of Weekend Homesteader is now available to preorder

(yay!), and we need help spreading the word. This more polished

version of the monthly ebooks I've been publishing for the last year

contains 368 pages of full color photos and text to guide you on the

path to self-sufficiency. Even if you've read all of the ebooks,

I suspect the $11 paperback will be worth a second read since I've

added in dozens of sidebars and three all new chapters. The

Weekend Homesteader won't be in print until October, but you can

preorder now and be the first on your block to hold a copy of the book

in your hands.

What do you have to do to

enter our giveaway? The paperback

edition of Weekend Homesteader is now available to preorder

(yay!), and we need help spreading the word. This more polished

version of the monthly ebooks I've been publishing for the last year

contains 368 pages of full color photos and text to guide you on the

path to self-sufficiency. Even if you've read all of the ebooks,

I suspect the $11 paperback will be worth a second read since I've

added in dozens of sidebars and three all new chapters. The

Weekend Homesteader won't be in print until October, but you can

preorder now and be the first on your block to hold a copy of the book

in your hands.

To spread the word,

choose one or more of the following options, then leave a comment below

telling me how many times to enter you in the drawing. (Each way

you spread the word equates to one entry.)

- Preorder the book on Amazon.

- Tell your friends via facebook, google plus, your blog, email, twitter, or even plain old face-to-face chatting.

- Leave a review on any of my ebooks on Amazon. (You can see them all in one place on my author page, or just search for my name. Please only leave reviews on books you've read.)

- A very easy freebie for all of you --- click the "like" button on the Amazon page of my paperback.

- Some other ingenious way of spreading the word --- you decide!

So, if you preordered

two copies of the book, posted on facebook and

your blog, and left two reviews, you'd be entered six times! The

more times you enter, of course, the more likely you are to win.

(Just be sure to leave a comment on this post before midnight on April

13 to tell me how many times to put your name in the hat.) Thanks

so much in advance for entering and helping spread the word!

Mark

and I were looking forward to expanding our horizons at the ACRES USA

conference this

winter, but after attending the pre-conference, we were quickly citied out

and fled back to the farm. The

good news is that ACRES has a policy of giving you half your conference

fee as a credit at their store if you're unable to attend, which was

enough to purchase a "free" audio version of the entire conference to

enjoy at our leisure!

Mark

and I were looking forward to expanding our horizons at the ACRES USA

conference this

winter, but after attending the pre-conference, we were quickly citied out

and fled back to the farm. The

good news is that ACRES has a policy of giving you half your conference

fee as a credit at their store if you're unable to attend, which was

enough to purchase a "free" audio version of the entire conference to

enjoy at our leisure!

I love to read, but have

a harder time buckling down to listen to audio, so I didn't crack the

first mp3 file until chicken waterer orders started to heat up in

March. Since then, I've been listening to one or two lectures per

week as I build do it yourself kits, skipping over the less interesting

topics but finding lots of intriguing information in others.

This week's lunchtime series

is a summary of the first four of those interesting lectures ---

biodynamics, cover crops, plant secondary metabolites, and brix.

I found some lectures a bit kooky, just as Roland suspected, but there

was at least a bit of tantalizing information in each. Stay tuned

for those tidbits at noon all week, and then for more summaries

throughout the spring and summer.

This week's lunchtime series

is a summary of the first four of those interesting lectures ---

biodynamics, cover crops, plant secondary metabolites, and brix.

I found some lectures a bit kooky, just as Roland suspected, but there

was at least a bit of tantalizing information in each. Stay tuned

for those tidbits at noon all week, and then for more summaries

throughout the spring and summer.

(As a side note, these

photos are totally irrelevant to the lunchtime series. I'm

enjoying how beautiful the kale is as

it starts to go to seed.)

| This post is part of our ACRES conference lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I've asked at least 3

separate feed store clerks if I could get my chicken feed non-medicated.

Without exception each of them gave me a look as if I was asking them

to break a law of physics.

I stopped asking and just

took what they had to offer, and then some friends of ours who have a pastured

livestock operation invited us to join their bulk chicken feed

purchase.

A place called Sunrise

Farm sells non-medicated feed for just a little more than the feed

store prices. Anna's got the details of the high

quality chicken feed ingredients over on our Avian Aqua Miser blog.

Remember

last year's tomato

alley? We

lined most of these juicy morsels up against the fence between the mule

garden and the chicken pasture since that's the sunniest spot in our

vegetable garden. This year, we're rotating the tomatoes into the

forest garden and renaming that long row "asparagus alley".

Remember

last year's tomato

alley? We

lined most of these juicy morsels up against the fence between the mule

garden and the chicken pasture since that's the sunniest spot in our

vegetable garden. This year, we're rotating the tomatoes into the

forest garden and renaming that long row "asparagus alley".

We currently have about

thirty asparagus plants that are just starting to be old enough to pick

heavily, but the beds produce late because I sited them in the part of

the garden that's shaded by the hill all winter, keeping the soil

cold. On the one hand, planting the asparagus on the shady side

of the garden makes sense since the perennials can handle less than

full sun in the summer. But on the other hand, it means we didn't

get our first real flush of large spears until Friday --- pretty late

considering how warm our spring has been.

I had planned to expand the

planting anyway because thirty asparagus plants isn't really enough for

two people hungry from a long winter with only leafy greens as our

fresh produce option. One of our "all-male"

asparagus plants

turned out to be a female, so I collected its fruits last fall,

fermented out the seeds, and dried them for spring planting.

I had planned to expand the

planting anyway because thirty asparagus plants isn't really enough for

two people hungry from a long winter with only leafy greens as our

fresh produce option. One of our "all-male"

asparagus plants

turned out to be a female, so I collected its fruits last fall,

fermented out the seeds, and dried them for spring planting.

Planting asparagus from

seed might be a bit slower than buying roots, but it's vastly cheaper

(free if you save your own seeds). And many folks believe that

you lose a year when setting out roots due to transplant shock,

resulting in full production at the same time from seeds or transplants.

I'm looking forward to even

earlier (and more abundant) asparagus in four or five years. I

think the ferny fronds will look nice along the chicken pasture fence

too, and will give our flock a bit of summer shade. Maybe the

chickens will even munch on passing asparagus

beetles?

I'm looking forward to even

earlier (and more abundant) asparagus in four or five years. I

think the ferny fronds will look nice along the chicken pasture fence

too, and will give our flock a bit of summer shade. Maybe the

chickens will even munch on passing asparagus

beetles?

Karl Dallefeld spoke at the

ACRES USA conference about "capturing maximum value from diversity of

plant species on your farm", mostly in relation to mixtures of cover

crops. Dallefeld has experimented extensively with cover crops on

his eastern Iowa farm, and much of his talk consisted of a who's who of

top cover crops for various applications. His recommendations by

category include:

Karl Dallefeld spoke at the

ACRES USA conference about "capturing maximum value from diversity of

plant species on your farm", mostly in relation to mixtures of cover

crops. Dallefeld has experimented extensively with cover crops on

his eastern Iowa farm, and much of his talk consisted of a who's who of

top cover crops for various applications. His recommendations by

category include:

- Scavenging nitrogen - rye, sorghum-sudangrass, radish, rapeseed, ryegrass

- Nitrogen fixation - legumes (especially clovers)

- Quick spring cover - buckwheat, sorghum-sudangrass, berseem clover, medic

- Late planted winter cover

- annual ryegrass, rye, oats, radish, rape, turnips

- Erosion control - barley, rye, sorghum-sudangrass, cowpeas

- Building soil - rye, sorghum-sudangrass, sweetclover, woollypod and hairy vetch

- Loosening compacted soil - radish

- Suppressing nematodes - brassicas (only if tilled in)

- Dealing with high pH - mustard, berseem clover, ryegrass, vetch

- Fighting weeds - rye, oats, buckwheat, radish, berseem clover, chickling and other vetches, cowpeas, subclover

- Quick, temporary pastures - annual ryegrass, oats, wheat, sorghum-sudangrass, berseem clover, crimson clover, white clover, red clover

You'll notice that most

categories include several options, and Dallefeld prefers to mix lots

of species together when planting cover crops. His goal is to

include at least one legume, one grass, and one non-legume forb (aka

everything else) in each mixture, on the assumption that a more diverse

cover crop assortment will do its job better. For example, he

might plant mustard, berseem clover, ryegrass, and a vetch all at once,

figuring that the clover and vetch will add nitrogen to the soil, the

mustard will feed pollinators and reduce the number of nematodes, and

the ryegrass will build organic matter.

You'll notice that most

categories include several options, and Dallefeld prefers to mix lots

of species together when planting cover crops. His goal is to

include at least one legume, one grass, and one non-legume forb (aka

everything else) in each mixture, on the assumption that a more diverse

cover crop assortment will do its job better. For example, he

might plant mustard, berseem clover, ryegrass, and a vetch all at once,

figuring that the clover and vetch will add nitrogen to the soil, the

mustard will feed pollinators and reduce the number of nematodes, and

the ryegrass will build organic matter.

I was particularly

struck by Dallefeld's explanation of when to kill cover crops depending

on your goals. He explains that young, succulent plants (like

buckwheat at the bloom stage) provide quick nutrients while lignified

(aka mature and woody) cover crops tie up nutrients at first, but end

up building humus in the long run. That's why we use

buckwheat in the summer in short windows between vegetables and save

oats for over-wintering, since the latter have time to rot down a

bit before we plant into them the next year.

Dallefeld's experiences are

with cover crops in their mainstream, large-scale application.

Generally, he sows cover crops into newly tilled fields and then tills

them back into the ground before planting a vegetable, so you should be

careful about using his favorite varieties in a no-till garden.

Still, we can all take his wisdom to heart --- more diversity in the

garden is nearly always better. Maybe I need to continue

expanding my selection of cover crops beyond the tried and true.

Dallefeld's experiences are

with cover crops in their mainstream, large-scale application.

Generally, he sows cover crops into newly tilled fields and then tills

them back into the ground before planting a vegetable, so you should be

careful about using his favorite varieties in a no-till garden.

Still, we can all take his wisdom to heart --- more diversity in the

garden is nearly always better. Maybe I need to continue

expanding my selection of cover crops beyond the tried and true.

| This post is part of our ACRES conference lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

We put together a storage

shed this afternoon.

It's one of those plastic

resin Rubermaid kits.

Total cost was around 360

dollars. Anna worked 3 hours and I came along at the end and helped for

an hour. It comes with a nice 37 page instruction book and it all fit

in a box the size of a coffin.

We talked about maybe

building something out of wood, but our recent high

grade chicken feed

purchase put us in a spot where we needed storage fast, and this was

the quick and easy route.

Let's all wish Joey a happy birthday

today! You may not have the same fond memories I do of walking on

the train tracks on the way home from school, a book under your nose

and your big brother on the rail in front of you. But we all owe

Joey a huge thank you for making the technical side of this blog possible. Most

recently, he coded a plugin to allow you to sign up for email

notifications of responses to your comments --- have you noticed?

We celebrated Joey's birthday

a couple of days early with a picnic at Natural Tunnel State

Park. The wildflowers are currently in full bloom on the trail

above the tunnel, and if you live in the area, this is a walk not to be

missed.

We celebrated Joey's birthday

a couple of days early with a picnic at Natural Tunnel State

Park. The wildflowers are currently in full bloom on the trail

above the tunnel, and if you live in the area, this is a walk not to be

missed.

Three turkey vultures

treated us to a shadow light show that's impossible to describe, but

was breath-taking in person. I also spent far too long peering

through the zoom lens of my camera (since I forgot my binoculars) to

figure out what those strange birds were roosting on the cliffs.

Yup, those are aptly named Rock Doves...aka the kind of pigeons you see

in city parks. Boy was I embarassed when I realized I hadn't

recognized pigeons (but intrigued to see them in a semi-natural

habitat).

Joey went on to embrace

his Hobbit side

while we zipped on down the road to pick

up chicken feed.

More photos of cute livestock soon!

Joey went on to embrace

his Hobbit side

while we zipped on down the road to pick

up chicken feed.

More photos of cute livestock soon!

Don't

forget to preorder your copy of Weekend

Homesteader for tips on fitting a self-sufficient life into your

busy schedule.

One of the things I'd hoped

to get out of the ACRES USA conference was an opportunity to answer

questions like --- is biodynamics kooky or is it a valid method of

increasing the biological stability of a farming ecosystem? After

listening to Gena Nonini's "Biodynamic journey" presentation, I'm

leaning toward the answer --- biodynamics is both.

One of the things I'd hoped

to get out of the ACRES USA conference was an opportunity to answer

questions like --- is biodynamics kooky or is it a valid method of

increasing the biological stability of a farming ecosystem? After

listening to Gena Nonini's "Biodynamic journey" presentation, I'm

leaning toward the answer --- biodynamics is both.

Nonini grew up on a

conventional (aka chemical) farm in California, so her journey in the

biodynamic direction wasn't well received by her family and

neighbors. She leased 90 acres of wine grapes from her parents in

1991, and soon realized that chemical farming was terrible for her

health, and wasn't going to allow her to make a living either.

Nonini's response was to

slowly but surely start focusing on organic inputs and on diversifying

her operation. She followed the biodynamic principle of creating

"preparation 500" --- filling a cow horn with cow manure and burying it

in the ground to age for a few months before applying the compost to

her soil. She also added citrus trees and vegetables to the farm,

figuring the biodiversity would help prevent pests organically and

would also ease the financial strain if one crop failed.

Nonini's response was to

slowly but surely start focusing on organic inputs and on diversifying

her operation. She followed the biodynamic principle of creating

"preparation 500" --- filling a cow horn with cow manure and burying it

in the ground to age for a few months before applying the compost to

her soil. She also added citrus trees and vegetables to the farm,

figuring the biodiversity would help prevent pests organically and

would also ease the financial strain if one crop failed.

In her lecture, Nonini

argued that the health of biodynamic farms can't be explained by

"substances", but instead by "forces". (Yes, she even talked

about communing with the gnomes.) This is where she lost me, and

why I've considered biodynamics kooky in the past. I'm quite

willing to believe that preparation 500 might be very valuable to soil

--- maybe the horn acts a bit like biochar and increases microorganism

populations dramatically in the enclosed manure. But creating a

spiritually-based agriculture system seems like a copout to me. I

always want to know how things operate so I can decide when to use them

and how to make them work even better.

Biodynamic agriculture has

developed a large following as the term "organic" continues to be taken

over by large agriculture companies that care more about the bottom

line than about the health of the farm ecosystem. However, I'm

afraid I'll stick to the term "permaculture" for now if Nonini is a

typical example of the biodynamic movement. I've got another

biodynamic talk to listen to, though, so maybe I'll change my tune in

the next ACRES lunchtime series.

Biodynamic agriculture has

developed a large following as the term "organic" continues to be taken

over by large agriculture companies that care more about the bottom

line than about the health of the farm ecosystem. However, I'm

afraid I'll stick to the term "permaculture" for now if Nonini is a

typical example of the biodynamic movement. I've got another

biodynamic talk to listen to, though, so maybe I'll change my tune in

the next ACRES lunchtime series.

| This post is part of our ACRES conference lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Mother Nature is threatening

to equalize our unseasonably warm Spring with some below freezing

temperatures tonight.

We covered vulnerable crops

with Agribon material and weighed it

down with old chimney bricks.

Brrrrrrr.

We

reveled in spring. We watched the flowers with joy, started crops

way too early, and basked in the warm sunshine.

We

reveled in spring. We watched the flowers with joy, started crops

way too early, and basked in the warm sunshine.

And now it's time for

our comeuppance. As you can see from this webcam shot, the chicks weren't

pleased when Friday morning temperatures were in the mid to high

20s. I wasn't either --- the weather forecast had promised me a

low of 36 and I'd only half-heartedly covered a few strawberry beds.

I don't even want to

start telling you everything that got nipped last weekend, because I

suspect more kicked the bucket last night. We went ahead and covered the rest of the strawberries

Wednesday, along with broccoli, cabbage, Swiss chard, and carrot

seedlings.  In some cases, this equates

to closing the barn door after the horse has bolted, but I figured we

were better off safe than sorry.

In some cases, this equates

to closing the barn door after the horse has bolted, but I figured we

were better off safe than sorry.

I'm more concerned about

a fruitless summer than spring setbacks, though. The kiwi leaves

turned black after Friday's freeze and some of our new grape leaves

were slightly nipped. Only time will tell whether last night's

(and tonight's) cold hit the tree fruits.

And then there are the

wild trees. No, it doesn't make any difference to our livelihood,

but I remember how depressing it was to walk around in the woods all

summer six years ago when a late frost nipped back the young buckeye

leaves. Here's hoping the woodland microclimate will prevent at

least that!

Jerry

Brunetti's lecture was titled "Achieving the holy grail of crop health:

Plant secondary metabolites". That probably sounds a bit

yawn-worthy if you're not a plant geek, but it turns out his talk was

my favorite from the conference so far. (In the interest of full

disclosure, though --- I am a plant geek.)

Jerry

Brunetti's lecture was titled "Achieving the holy grail of crop health:

Plant secondary metabolites". That probably sounds a bit

yawn-worthy if you're not a plant geek, but it turns out his talk was

my favorite from the conference so far. (In the interest of full

disclosure, though --- I am a plant geek.)

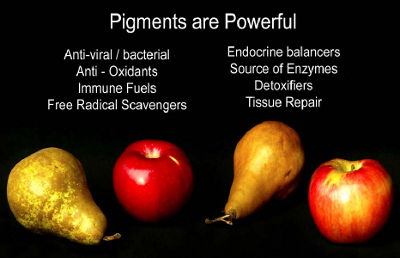

So, what are plant

secondary metabolites, and why should we care about them?

The term refers to every chemical that makes up a plant except for the

big three --- carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. The scent of a

flower, the spiciness of a pepper, and the color of an apple are all

plant secondary metabolites. So are the chemicals released by

caterpillar-nibbled trees to warn the next tree down the lane to build

anti-caterpillar chemicals proactively, as well as the attractants

emitted by plant roots to tempt soil microorganisms to stop by.

The

chemicals that give plants intriguing tastes are all plant secondary

metabolites, and so are compounds like lycopene and salicylic acid,

which help prevent prostate cancer and heart attacks,

respectively. Brunetti explains that there are tens of thousands

of plant

secondary compounds produced for reasons that include attracting

pollinators and seed dispersers, defending the plant from ultraviolet

light and herbivores, and communicating with plants, insects, and soil

microorganisms.

The fact that so many of the

compounds impact our health (positively or

negatively) is merely a side effect from the plants' point of

view. Plants create secondary metabolites because the chemicals

make their lives easier --- since a tree can't run away from problems

or travel to find true love, it has to repel the one and attract the

other. (Sounds like my life on the farm....)

The fact that so many of the

compounds impact our health (positively or

negatively) is merely a side effect from the plants' point of

view. Plants create secondary metabolites because the chemicals

make their lives easier --- since a tree can't run away from problems

or travel to find true love, it has to repel the one and attract the

other. (Sounds like my life on the farm....)

But production of these

chemicals comes at a cost. Plants

constantly have to weigh the pros and cons of using their limited

energy to make carbohydrates, fats, and proteins --- allowing them to

grow and reproduce --- or to make secondary metabolites of various

sorts. In the wild, plants usually create a bit of both, focusing

on secondary metabolites more when they're subtly stressed, but not so

injured that they're wilting away.

In an agricultural

setting, the stakes are different. Farmers try to protect

our crops from all problems, which means the plants have little reason

to produce secondary metabolites and can simply grow big and

tall. While that means more pounds of vegetables on our plates,

the lower concentrations of secondary metabolites make the food less

tasty and nutritious. Maybe that's why vineyard keepers believe

the best wine comes from grapes that had to struggle a little?

In

addition to lacking the incentive to make secondary metabolites, some

cultivated plants also lack the ability. Micronutrients like boron, copper,

aluminum,

manganese, and zinc are all essential for the production of secondary

metabolites but chemical farmers figure crops can get by without

micronutrients as long as they're well dosed up with some

10-10-10. I guess that's why I

was able to taste a micronutrient

deficiency in my strawberries --- the lack of minerals

relates

directly to the secondary metabolites that we

In

addition to lacking the incentive to make secondary metabolites, some

cultivated plants also lack the ability. Micronutrients like boron, copper,

aluminum,

manganese, and zinc are all essential for the production of secondary

metabolites but chemical farmers figure crops can get by without

micronutrients as long as they're well dosed up with some

10-10-10. I guess that's why I

was able to taste a micronutrient

deficiency in my strawberries --- the lack of minerals

relates

directly to the secondary metabolites that we  perceive as flavor.

perceive as flavor.

So how do you grow

the most delicious and nutritious fruits and

vegetables possible? Simply feed the soil well-rounded organic

amendments like compost and mulch, and don't wipe out every last

disease and pest. You'll get lower yields, but what you do grow

will be richer in flavor and nutrition.

Learn to grow healthy plants from the ground up in Weekend Homesteader.

| This post is part of our ACRES conference lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our new chicks have outgrown

their small

automatic feeder.

The new one cost around 15

dollars.

A large shelf bracket with a

mug hook is all it took to rig it so it can be suspended off the ground.

We had a small debate on the

issue of making a lid for it. It didn't come with one, but now that I'm

looking at this picture I'm thinking I might need to think about one if

they figure out how to roost on the bracket.

Do

you want to grow a variety of gourmet salad greens? Seed mixtures

are available, but they're generally quite expensive, and can also be

problematic in the garden. I've also found that the lettuce

varieties that come in seed mixtures aren't as tasty as the ones I've

hand-picked to suit our palates and garden.

Do

you want to grow a variety of gourmet salad greens? Seed mixtures

are available, but they're generally quite expensive, and can also be

problematic in the garden. I've also found that the lettuce

varieties that come in seed mixtures aren't as tasty as the ones I've

hand-picked to suit our palates and garden.

On the other hand, who

doesn't enjoy a diverse array of colors, shapes, and flavors on their

plate? Here are my tips for making your salad bowl gourmet the

Walden Effect way:

- Plant non-lettuce salad greens in a separate bed. Many seed mixtures include non-lettuces like arugula, spinach, and Asian greens for an extra flavor burst. However, these salad greens tend to grow differently than lettuce, maturing at a different rate, so they do better in their own garden bed. It's easy to snip a few leaves of arugula to add to your salad bowl while you're in the garden collecting dinner, and separating out the non-lettuces also allows you to add more or less of the spicy plants depending on your guests and meal plan.

Mix lettuces by hand. When I was

ordering seeds this spring, the cheapest salad seed mixture at Johnny's

was $14.65 per quarter pound. In contrast, my favorite green leaf

lettuce (Black-seeded Simpson) was $7.45 per quarter pound and the

equally delectable Red Saladbowl was $9.30 per quarter pound. I

bought the red and green leaf lettuce seeds separately, mixed them as I

tossed the seeds in the bed, and saved 43%. (I could also have

given each lettuce its own bed, but different varieties of lettuce play

well together, so there was no real reason to segregate them.

However, some unusual lettuces like escarole might do better alone.)

Mix lettuces by hand. When I was

ordering seeds this spring, the cheapest salad seed mixture at Johnny's

was $14.65 per quarter pound. In contrast, my favorite green leaf

lettuce (Black-seeded Simpson) was $7.45 per quarter pound and the

equally delectable Red Saladbowl was $9.30 per quarter pound. I

bought the red and green leaf lettuce seeds separately, mixed them as I

tossed the seeds in the bed, and saved 43%. (I could also have

given each lettuce its own bed, but different varieties of lettuce play

well together, so there was no real reason to segregate them.

However, some unusual lettuces like escarole might do better alone.)

No matter where the

seeds come from, leaf lettuce is the very first crop I'd recommend

beginning gardeners plant, as long as they hurry up and do so before

summer heat kicks in. Plant your lettuce today and you can be

eating it within a month, and that dollar's worth of seed could feed

you up to 60 meals! Now that's low cost gourmet food.

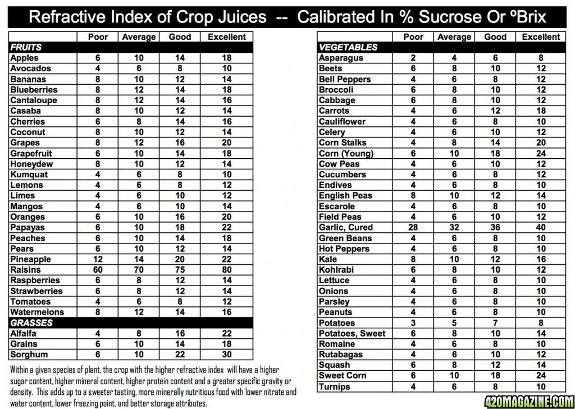

"Brix" is one of those terms

tossed around by folks in alternative agriculture circles that I

considered a little kooky in the past. The idea is simple --- you

use a meter to determine the percent by weight sugar in a plant, which

gives you a rough estimate of the nutritional quality of the food since

more nutritious crops are usually also sweeter.

"Brix" is one of those terms

tossed around by folks in alternative agriculture circles that I

considered a little kooky in the past. The idea is simple --- you

use a meter to determine the percent by weight sugar in a plant, which

gives you a rough estimate of the nutritional quality of the food since

more nutritious crops are usually also sweeter.

Even though I agree with

the theory behind brix, I used to roll my eyes at the

implementation. I can taste the difference in brix between my

homegrown vegetables and the ones in the grocery store, so why buy a

$100 meter?

Glen Rabenberg's talk on

"Improving crop quality using readily available tools" helped me

realize that my understanding of brix in the garden is overly

simplistic. He doesn't just check the brix of crops being

harvested; he monitors plants at various stages of their life span to

prevent disease and insect problems.

Rabenberg asserts that at

increasing levels of brix, farms become healthier in a holistic

fashion. Disease fungi and thrive at a brix below 7, but when the

leaves of a plant reach a brix of around 10 to 11, Rabenberg sees

drought resistance in the crops and fewer weeds nearby. At 13 to

14, he begins to see resistance to pest insects. Having recently

seen in a scientific source that the fire blight

bacteria are deterred by high levels of sugar in pear nectar, I'm willing to believe that

there's some truth to Rabenberg's ideas.

Rabenberg asserts that at

increasing levels of brix, farms become healthier in a holistic

fashion. Disease fungi and thrive at a brix below 7, but when the

leaves of a plant reach a brix of around 10 to 11, Rabenberg sees

drought resistance in the crops and fewer weeds nearby. At 13 to

14, he begins to see resistance to pest insects. Having recently

seen in a scientific source that the fire blight

bacteria are deterred by high levels of sugar in pear nectar, I'm willing to believe that

there's some truth to Rabenberg's ideas.

So, how do you raise the