archives for 02/2012

I hope that when I reported

that the

Persephone Days were over, you didn't rush out to

plant your spring vegetables. Once daylength is longer than ten

hours, surviving crops like kale will start growing again, but that

doesn't mean the

ground is warm enough for seeds to sprout.

I hope that when I reported

that the

Persephone Days were over, you didn't rush out to

plant your spring vegetables. Once daylength is longer than ten

hours, surviving crops like kale will start growing again, but that

doesn't mean the

ground is warm enough for seeds to sprout.

Lettuce, onions, and

spinach can all handle soil temperatures as low as 35 while most other

spring crops like the earth to have warmed to at least 40 degrees

Fahrenheit. I tested the soil

temperature in the

sunniest part of our garden last week, and the ground underneath our

quick hoops was just barely 35 degrees, while unprotected soil was

hovering right around freezing.

Most of the plants under

my quick hoops are starting to grow again, but the tatsoi totally

perished in the winter cold. That means I had a spot just waiting

to plant spring lettuce! Rip out a few weeds, toss down a bucket

of composted manure, then sprinkle on lettuce seeds, and the first

garden bed of 2012 is seeded for March harvests.

Many of us get so excited

when we learn about multi-species

grazing and about rotational

pastures that we want to create a vibrant ecosystem

overnight. But Greg Judy cautions us to slow down.

Many of us get so excited

when we learn about multi-species

grazing and about rotational

pastures that we want to create a vibrant ecosystem

overnight. But Greg Judy cautions us to slow down.

If you already manage a

pasture, he recommends not increasing your stocking rate or expanding

into multiple species for at least two years. It will take you

that long to improve the quality of your soil so that it can handle

more feet.

Meanwhile, Greg

recommends that you figure out what your centerpiece animal is and

learn the intricacies of its care before bringing new animals in.

Yes, adding more species can make the patsuring system work more

efficiently, but so will focusing on what's most important rather than

scattering your attention in five different directions.

Meat animals make much

better starter livestock than dairy animals do. Making milk

requires a lot of energy, and it's tough (although possible) to keep

dairy animals healthy on pasture alone. In addition, a quality

milk cow is worth a lot more than a meat cow, so there's less financial

risk as you muddle your way up the learning curve.

Finally, Greg recommends

that you pay as close attention to yourself as you do to the

pasture. If you work a full time job and plan to pasture

livestock in your spare time, don't start with a complex dairy cow

rotation where you need to move animals seven times a day. On the

other hand, if you're unemployed and are willing to put in the time,

you can feed many more animals on the same acreage if you're willing to

rotate often so that high quality food is always available. Maybe

in a few years, you'll be able to run half a dozen different kinds of

livestock on that same pasture.

This post is part of our Mob Grazing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Mob Grazing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

I've been experimenting with

alternative heating methods for the new Rajkumar

oil expeller.

The soldering iron pictured

above failed miserably.

It did a good job of heating

the metal, but those things were never designed to be left on for more

than a minute, which is why it has a push button trigger instead of a

toggle switch. I knew this, but thought it could handle just a few

minutes more. That's when the plastic case around the heating element

melted. Now I need to find a new soldering iron.

The next round of experiments

will involve an electric

pipe heater.

I saw Mark peeling the

bark off the walnut logs we were stacking into the

woodshed and realized that he was right --- barkless logs will probably

dry faster. Even dry bark doesn't make good firewood, so I

decided to snag the biomass for my garden.

My first impulse is to

see how the bark fares as the kill layer of a kill

mulch. I never

have enough corrugated cardboard to go around --- maybe a couple of

thicknesses of bark will do just as well?

Well planned pasturing systems can heal the

earth --- and can take advantage of natural systems to keep the

livestock healthier. Greg Judy puts up tree swallow boxes since

one adult can eat 8,000 flies per day, leading to happy cows.

Meanwhile, he pays close attention to the critters in and on the soil,

watching dung beetles roll manure down tunnels into the earth and

counting 462 worms in a single cow pat. He considers spiders to a

prime indicator of pasture health since these predators need to eat

lots of insects to stay alive, and insects thrive in rich, organic

matter-filled soil.

Well planned pasturing systems can heal the

earth --- and can take advantage of natural systems to keep the

livestock healthier. Greg Judy puts up tree swallow boxes since

one adult can eat 8,000 flies per day, leading to happy cows.

Meanwhile, he pays close attention to the critters in and on the soil,

watching dung beetles roll manure down tunnels into the earth and

counting 462 worms in a single cow pat. He considers spiders to a

prime indicator of pasture health since these predators need to eat

lots of insects to stay alive, and insects thrive in rich, organic

matter-filled soil.

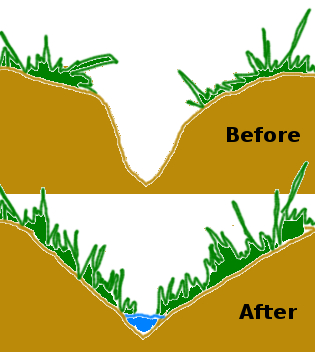

Other parts of Greg's

pasturing ecology seem less intuitive. He believes that careful

mob grazing can heal gullies and riparian

areas. He mob grazes steep sided gullies three or four times per

year, knocking the banks down so that vegetation can gain a

foothold. While I'm not sure his system would work in very wet

climates (his waterways tend to dry up in the summer), Greg's system

has created vegetated waterways that capture his neighbor's eroding

topsoil (and precious water) each time it rains. "It doesn't

matter how much rain you get," said Greg. "It matters how much

you keep."

This post is part of our Mob Grazing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: This post is part of our Mob Grazing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Our 14 foot long metal

roofing panels came in today.

The

guy we hired said he won't have much trouble walking the material

across the creek and back to the barn.

Yes...he actually has seen

the creek and driveway first-hand when he came out to give us the

estimate. I'm guessing he has plans to make some sort of stretcher so a

guy on each end can lift maybe 4 or 5 at a time?

I started my most

successful forest garden island very simply. I planted

the tree in a raised bed, then dumped weeds around the bed's edges for

three years.

The mounds of weeds rotted down to expand the original raised bed,

creating rich dirt that extended beyond the tree's canopy. I highly

recommend this method since it requires you to maintain your focus on

the centerpiece tree, giving it a few years to get established before

the tree has to compete with anyone else.

The photo above shows the

three year old peach tree in August 2009. At this point, my

well established peach was ready to handle understory plants, so I

transplanted comfrey and bee balm into the partial shade beneath the

peach's canopy, and fennel, echinacea, rhubarb, and Egyptian onions in

the sun.

May

of the next year, the forest garden island was in full swing. In less successful

forest garden islands, I had planted comfrey under younger peach trees

in poor soil, and the comfrey

stole nitrogen from the tree. But this more

established peach had no problem shading the comfrey enough that the

understory plant behaved.

May

of the next year, the forest garden island was in full swing. In less successful

forest garden islands, I had planted comfrey under younger peach trees

in poor soil, and the comfrey

stole nitrogen from the tree. But this more

established peach had no problem shading the comfrey enough that the

understory plant behaved.

You'll notice that

fennel, echinacea, and rhubarb have disappeared --- these plants didn't

like being transplanted in the summer heat. However, the Egyptian

onions were thrilled with their new home and thrived even during my

summer neglect.

That spring, I seeded

poppies amid the Egyptian onions, which added a lot of beauty, but

won't be repeated. I love puttering in my forest garden islands

in the winter, but in the  summer I'm too busy in the

vegetable garden to give them any care. Since

annuals tend to require bare ground, which has to be weeded, they're

out of the running as forest garden plants.

summer I'm too busy in the

vegetable garden to give them any care. Since

annuals tend to require bare ground, which has to be weeded, they're

out of the running as forest garden plants.

This second year of the

forest garden island was when our peach started producing --- over half

a bushel that summer. Meanwhile the

ecology of the island seemed to come into its own, attracting birds,

insects, and wild mushrooms.

Last year was the third

year of forest garden experimentation. The peach

had achieved its mature size and was starting to shade out the comfrey

and bee balm closest to the trunk. That allowed me to add another

type of understory plant --- shade lovers. I transplanted ramps right around the tree's

trunk and daffodils helter skelter throughout

the island. Both of these plants are early spring ephemerals,

which are active in the spring before the tree canopy shades them out,

then die back when summer arrives.

Where will the island go

from here? I'm experimenting with more shade-loving species this

spring --- goldenseal

and ginseng.

Meanwhile, if I get around to it, I plan to transplant some flowering

perennials into the sunny zone --- probably bee balm, echinacea, and

fennel, since I have them around in excess.

A wild elderberry sprang

up at the edge of the forest garden island a few years ago, and I left

it alone since it seemed to be far enough away that it doesn't compete

with the peach.  Pollinators seem to love the

flowers, and the birds enjoy the fruits. (I know elderberries are

edible for humans too, but I'm not enough in love with the taste that I

feel the need to fight off the birds, who really love the taste.)

Pollinators seem to love the

flowers, and the birds enjoy the fruits. (I know elderberries are

edible for humans too, but I'm not enough in love with the taste that I

feel the need to fight off the birds, who really love the taste.)

The island has stopped

expanding since the peach has achieved its final size, and I can feel

the ecosystem starting to reach a steady state. Annual

maintenance is now about the same as it would be for any other fruit

tree, but I

suspect the tree is healthier for the diverse ecosystem under and

around its canopy. Plus, we get to enjoy a bit of beauty right

outside the kitchen window. This is one of our most successful

permaculture experiments, and I highly recommend you try it out around

your own fruit trees.

If you've read my lunchtime

series on Voisin

grazing as well as

this one on mob

grazing,

you might be wondering which method is better. I suspect the

answer depends on what kind of animal you're trying to feed, and on how

healthy your pasture is to start with.

If you've read my lunchtime

series on Voisin

grazing as well as

this one on mob

grazing,

you might be wondering which method is better. I suspect the

answer depends on what kind of animal you're trying to feed, and on how

healthy your pasture is to start with.

Mob grazing has two

major benefits --- it heals the soil quickly, and

it also allows you to keep ruminants on pasture all winter without

feeding hay. On the other hand, Voisin grazing's tender grasses

and copious clover make this method more appropriate to non-ruminants

(like pigs and chickens), and to dairy animals that require high

quality feed.

Can you mix and match

the two systems to suit your own needs? I'm

not positive, but I suspect you could treat different paddocks in

different ways, stockpiling winter forage in one while grazing another

one close and often to promote the growth of clovers.

I'd be very curious to

hear from those of you who have tried either

system. What did you like about it? What problems did you

run into?

This post is part of our Mob Grazing lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

We got the golf

cart home without any trouble from the local sheriff.

Our mechanic found the

problem. It was a worn bearing. I was highly impressed with the way he

was able to replace it with a bearing that normally fits in a car. You

can't get Club Car parts online, only from a local

dealer.

I think he talked us into

upgrading the back springs, which will help with the heavy loads we

tend to haul.

Based on last year's onion

experiments, I've

decided to start my storage onions inside this winter. The other

option that worked well was to grow the onions under quick hoops in

soil doctored with biochar, but I only have one bucket

of the precious amendment and am not sure I want to "waste" it on

onions. (My quick hoops are all full of overwintering greens

anyway.)

Based on last year's onion

experiments, I've

decided to start my storage onions inside this winter. The other

option that worked well was to grow the onions under quick hoops in

soil doctored with biochar, but I only have one bucket

of the precious amendment and am not sure I want to "waste" it on

onions. (My quick hoops are all full of overwintering greens

anyway.)

So I headed out to the

old apple tree for some stump

dirt to use as

potting soil. I put the stump dirt directly into my seed starting

flats, wet it down, then lightly compressed the organic matter with my

fingers. After sprinkling seeds on top, I added a thin layer of

composted horse manure --- sometimes I use stump dirt alone as

potting soil, but the apple tree's rotted center didn't seem quite as

dark and rich as the organic matter I mine out of the beech tree

further away.

Assuming they come up

and grow, I'll transplant tiny onion sets at the beginning of

March. Although it seems rough to throw them into unprotected

ground so early, last year's transplants did find even without a quick

hoop. Maybe 2012 will be the year we finally delete the last

storebought vegetable from our diet?

I was trying to find some

information on cold pressing coconuts when I stumbled upon Youtube user

rawfoods and his unique

approach.

I was trying to find some

information on cold pressing coconuts when I stumbled upon Youtube user

rawfoods and his unique

approach.

1. Shred up the coconut.

2. Bake chunks in a dehydrator

at 118 degrees for 12 to 24 hours depending on humidity.

3. Slowly feed the dried

coconut pieces into a juicer where the fiber will get extracted from

the oil, which is very creamy and can be used as butter if you have the

proper coconut.

4. You may need to feed the

fiber back through to get additional oil out. This guy uses an Omega

8006 juicer.

5. Feed extracted fiber into a grain mill to make coconut flour.

More on this later when we

actually juice up some dried coconuts.

This photo is less than

stellar, but the behavior is too interesting not to share.

This photo is less than

stellar, but the behavior is too interesting not to share.

Mark called me over to

the window a few days ago to tell me that a bird was eating my praying

mantis egg cases.

Sure enough, this little Downy Woodpecker was pecking away at the

spongy blobs coating my peach tree twigs.

Generally, I like

praying mantises (even though the ones I have are invasive

species). But my rule of thumb is that even if an animal is

eating a beneficial insect, that's a good sign because it means I've

created a quality ecosystem that can support top level predators.

I wonder how many of my

other egg cases have been mined out? And I also wonder if the

mantis eggs have hatched into tiny mantises, spurring this attack.

I guess only the woodpeckers know for sure.

Back in December of 2009 I posted about having some

trouble with one of the golf cart lug nuts.

The hardware store didn't

have counter sunk nuts, so I got some regular nuts and added a set of

washers.

Turns out it was a mistake to take this short cut. Our mechanic fixed

the problem with proper

lug nuts on our last visit and kindly advised me to not do such a

thing again.

It's hard to be sure, but the

lug nut situation may have contributed to the bearing going bad.

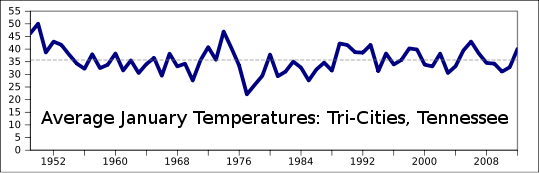

The first crocuses

opened on February 3 this year, and the Wood Frogs hit full chorus on

February 5. Meanwhile, the human chorus of "this is a crazy

winter" just gets louder and louder.

However, take a look at the

graph at the top of this page, showing average February temperatures at

our closest major weather station for the last 64 years. (We're

actually a zone colder than them, but the trends are mostly the same

here.) Isn't it interesting to see that January 2012 is only the

13th warmest year during that time period?

However, take a look at the

graph at the top of this page, showing average February temperatures at

our closest major weather station for the last 64 years. (We're

actually a zone colder than them, but the trends are mostly the same

here.) Isn't it interesting to see that January 2012 is only the

13th warmest year during that time period?

This post is in no way

related to global climate change, in case you're curious. No

single data point (and no comparison to the past 64 years) proves

anything in that respect. My thesis is --- our weather is always

erratic, so enjoy the crocuses when they come! I transplanted

some of our little beauties into our forest

garden island so I

can watch them out the kitchen window. I suspect no one else gets

so much mileage from a few little bulbs.

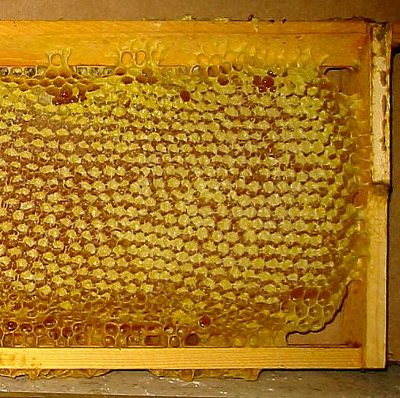

The

Practical Beekeeper: Beekeeping Naturally

by Michael Bush is the epitome of a self-published book. (Yes, I

do include my 99 cent ebooks in this category.) The text is chock

full of very good information that you can't find anywhere else, but is

definitely a bit rough around the edges.

The

Practical Beekeeper: Beekeeping Naturally

by Michael Bush is the epitome of a self-published book. (Yes, I

do include my 99 cent ebooks in this category.) The text is chock

full of very good information that you can't find anywhere else, but is

definitely a bit rough around the edges.

First of all, the author

is up front about the fact that the majority of the information can be

found for free on his website.

I've spent years dipping into his informative website and was quite

willing to pay a bit of money to have that information distilled into a

more linear format.

Unfortunately, I felt

like he didn't distill all that much.

There's no index, and the book is divided into beginner, intermediate,

and advanced sections, each of which covers most of the same topics in

different degrees of depth. So, to find out what Bush thinks

about strains of bees, I had to read the entire table of contents and

then flip through three different sections of the book. I even

noticed a few paragraphs that were included, verbatim, in multiple

sections.

Meanwhile, the book is

hardcover and large print, which means it's

hefty and sells for the scary price of $49. In retrospect, I

might have been better off with the ebook ($29 on his website) since

the photos are black and white and only moderate quality (meaning they

wouldn't lose anything by being viewed in eink.)

Whichever format you

choose, though, I highly recommend The Practical

Beekeeper to any intermediate beekeeper who's struggling to navigate

the maze of creating a chemical-free apiary. The book appears

daunting, but is actually an easy read and will definitely open your

eyes to

concepts you'd never considered.

| This post is part of our The Practical Beekeeper lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

It's been almost a year since

I used some scrap cardboard to block the wind in the used

pallet chicken coop.

There's no direct sun, and

the roof keeps it dry.

I'd say it's holding up

pretty good. I can notice some slight fading, but it seems to have

years left in it as an effective barrier.

My kitchen

forest garden island

gets all the love while the peach tree just one year younger is out of

sight and out of mind. No wonder my favorite peach's younger

sister has a canopy spread barely half the width of my darling kitchen

peach.

My kitchen

forest garden island

gets all the love while the peach tree just one year younger is out of

sight and out of mind. No wonder my favorite peach's younger

sister has a canopy spread barely half the width of my darling kitchen

peach.

I decided to begin to

remedy matters by expanding the little sister's raised bed. I

wheelbarrowed some partially decomposed weeds from the compost pile in

the chicken pasture to line one of the bed's edges, then added another

wheelbarrow load

of deep bedding,

lightly sprinkled atop the soil all around.

Meanwhile, I ripped up the mushroom

rafts (which I wasn't very pleased with) and rearranged the aging

logs in a big square around the peach. A friend and I weeded the

areas that were mulched last year, then I laid down a newspaper kill

mulch atop the parts of the square that were lawn. (I would have

preferred corrugated cardboard to newspaper, but you have to use what

you've got. Mom kindly saved all of these newspapers to be

firestarters, and I never ended up burning them since I had too much

junk mail.)

Meanwhile, I ripped up the mushroom

rafts (which I wasn't very pleased with) and rearranged the aging

logs in a big square around the peach. A friend and I weeded the

areas that were mulched last year, then I laid down a newspaper kill

mulch atop the parts of the square that were lawn. (I would have

preferred corrugated cardboard to newspaper, but you have to use what

you've got. Mom kindly saved all of these newspapers to be

firestarters, and I never ended up burning them since I had too much

junk mail.)

Finally, I topped it all

off with leaves and promised little sister peach to pay more attention

to her needs. With fruit trees, you don't really see the full

results of your actions until two seasons later, so I'll be waiting for

baskets of peaches in the summer of 2013.

PJ Chandler argued that the

Langstroth hive is the root of many of the problems currently facing

beekeepers.

Michael Bush agrees that honeybees are in trouble, but instead traces

the ills to:

PJ Chandler argued that the

Langstroth hive is the root of many of the problems currently facing

beekeepers.

Michael Bush agrees that honeybees are in trouble, but instead traces

the ills to:

- Raising sickly bees.

Bush argues that the modern methods of pouring chemicals into the hive

to keep pests at bay ends up selecting for resistant super-pests...and

for wimpy bees that wouldn't be able to survive without

chemicals. In addition, since most honeybees now come from only a

few beekeeping companies, we've restricted the gene pool so much that

we're raising only a few inbred strains of bees, none or few of which

have the ability to live in a chemical-free hive. These bees have

also been bred to use less propolis, which might make it easier for the

beekeeper to pry the hive apart, but also makes allows viruses

to thrive among the bees.

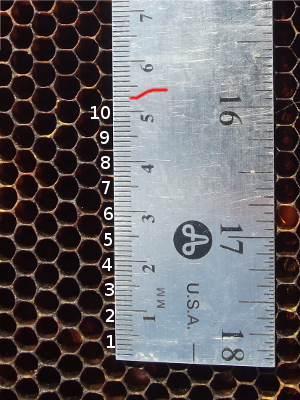

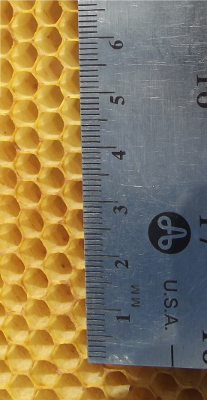

Using foundation that makes

bees sick.

I've written before that using foundation in

your hive makes your bees

create larger celled comb than they naturally would, which helps out

varroa mites. But did you know that the foundation you put in

your hive is processed beeswax from someone else's hive...who almost

certainly treated with lots of chemicals? The wax is impregnated

with pesticides, which causes drones raised on that foundation to be

less fertile and queens who mate with those drones to fail nine times

faster than a healthy queen would.

Using foundation that makes

bees sick.

I've written before that using foundation in

your hive makes your bees

create larger celled comb than they naturally would, which helps out

varroa mites. But did you know that the foundation you put in

your hive is processed beeswax from someone else's hive...who almost

certainly treated with lots of chemicals? The wax is impregnated

with pesticides, which causes drones raised on that foundation to be

less fertile and queens who mate with those drones to fail nine times

faster than a healthy queen would.- Upsetting the natural ecology of

the hive.

A healthy hive isn't just a couple of thousand bees; it also

includes beneficial fungi, bacteria, yeasts, mites, and insects.

It's helpful to think of a bee hive as a bit like our stomachs --- the

beneficial critters help "digest" (ferment) pollen while keeping the

hive from getting sick by crowding out pathogens. Using chemicals

in the hive is like taking antibiotics every day --- you kill the good

microorganisms along with the bad, so the system doesn't work as

well. In addition, feeding sugar water (pH 6.0) instead of

leaving bees enough honey (pH 3.2 to 4.5) creates an enironment that

helps the pathogens thrive.

Michael Bush's solutions --- while they can be hard to implement ---

are very simple. He says we have to stop using chemicals in our

hives, even if that means many of our colonies die and only the strong

remain. Deleting foundation allows bees to build clean wax at a

natural cell size. And we must make sure that our bees always

have enough honey rather than stealing too much and then feeding sugar

water. More on the specifics of his beekeeping method in

tomorrow's post.

| This post is part of our The Practical Beekeeper lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

I forget where I read about running a chainsaw with the bar upside down.

The logic is that the bar

will wear more evenly if you flip it every so often.

My system is to make the swap

each time I install a new or machine sharpened chain.

One of the best things

about leaves as mulch is that they're totally free. If you live

in town and pay attention, you can probably snag bags of leaves off the

curb on trash day during the fall. But if you're a rural dweller

like me, you'll want to head into the woods to find your mulch.

One of the primary

purposes of mulch in the garden is to prevent weeds from growing, so

it's essential that you rake leaves from weed-free areas. Mature

forests (or yard trees over manicured lawns) are your best bet --- our

younger forest areas are home to the invasive Japanese stilt grass, which I

don't want to introduce into my garden.

One of the primary

purposes of mulch in the garden is to prevent weeds from growing, so

it's essential that you rake leaves from weed-free areas. Mature

forests (or yard trees over manicured lawns) are your best bet --- our

younger forest areas are home to the invasive Japanese stilt grass, which I

don't want to introduce into my garden.

Look for dips in the

landscape and areas without a lot of understory growth for easiest leaf

harvests. The old logging road shown here tends to accumulate

leaves drifting down the hill, making it easy for me to scoop them up.

If you're able to drive

right to your leaf-gathering location, you'll probably choose to use a  leaf rake and some sort of

bin to gather leaves. But if you're walking off the beaten path,

I've found it easiest to simply scoop leaves with my hands into large

duffel bags, compacting the leaves frequently so you get the most

leaves per trip. To save your back, gather leaves during dry

weather. (Wet

leaves are heavy.)

leaf rake and some sort of

bin to gather leaves. But if you're walking off the beaten path,

I've found it easiest to simply scoop leaves with my hands into large

duffel bags, compacting the leaves frequently so you get the most

leaves per trip. To save your back, gather leaves during dry

weather. (Wet

leaves are heavy.)

The partially decomposed

duff beneath this year's leaves might be worth harvesting too, as long

as you don't mind creating a slight erosion potential in the spot where

you stole the leaves. Duff is heavier than undecomposed leaves,

which means it's less likely to blow away in the garden, and it is

often full of beneficial mycorrhizae which will boost the growth of

your garden plants. However, if you delve into the duff, try to

pay attention and don't harm the critters living there --- I moved this

tiny salamander to the side with a handful of humus and covered him

back over so he wouldn't dry out.

More in a later post

about the best ways to use leaf mulch in the garden. Meanwhile,

what tips would you add about leaf harvest?

So what does Michael Bush's

apiary look like? In some ways it's quite traditional --- he

mostly uses Langstroth hives and equipment from mainstream beekeeping

companies. However, he has made a few changes:

So what does Michael Bush's

apiary look like? In some ways it's quite traditional --- he

mostly uses Langstroth hives and equipment from mainstream beekeeping

companies. However, he has made a few changes:

- His boxes are all 8 frame mediums. Since the frames are all the same size, he can move honey and brood around if necessary and can allow an unlimited brood nest. In addition, the smaller boxes are about half the weight of a 10 frame deep, which makes his life much easier. The only downside is cost --- getting started requires nearly twice as much capital with Bush's method.

- He uses foundationless frames. As I've said over and over, foundationless frames help reduce varroa mite problems. In addition, you don't have the cost of buying foundation, the time drain of installing it, and the problematic chemicals that get carried into your hive from someone else's. Although we had a collapse after extracting honey from deep foundationless frames, you won't have problems if you stick to mediums or if you cut and crush.

He uses top entrances only.

Bush has plugged up his bottom entrances so that his bees go in and out

entrances in the top of the hive. Top entrances means he doesn't

need to worry about mowing around hives or about snow covering the

entrance in the winter. Mice are much less prone to sneak in a

top entrance, and he sees fewer problems from skunks and other pests

too. Finally, top entrances provide good ventilation and, when

combined with a layer of styrofoam on top of the hive, lead to little

winter condensation.

He uses top entrances only.

Bush has plugged up his bottom entrances so that his bees go in and out

entrances in the top of the hive. Top entrances means he doesn't

need to worry about mowing around hives or about snow covering the

entrance in the winter. Mice are much less prone to sneak in a

top entrance, and he sees fewer problems from skunks and other pests

too. Finally, top entrances provide good ventilation and, when

combined with a layer of styrofoam on top of the hive, lead to little

winter condensation.

- He doesn't treat hives.

Except in rare cases, Bush doesn't add any chemicals to the hive.

Even "organic" treatments like thymol

aren't generally on his agenda since these chemicals will kill

beneficial microorganisms in the hive.

- He breeds locally adapted queens.

Rather than buying new queens, Bush raises his own. But even with

these queens on hand, he doesn't requeen a hive unless absolutely

necessary --- for example, if the hive is failing while others are

thriving, or if the bees turn mean. Generally, his queens live to

be about three years old and then are naturally replaced by supersedure.

He feeds only honey

(usually.) In general, Bush tries to ensure that his bees have

enough of their own honey to make it through the winter. If he

has to feed, he usually feeds honey, but will sometimes feed dry sugar

in a pinch.

He feeds only honey

(usually.) In general, Bush tries to ensure that his bees have

enough of their own honey to make it through the winter. If he

has to feed, he usually feeds honey, but will sometimes feed dry sugar

in a pinch.

- He doesn't scrape anything out of the hive. Bush believes that the burr comb that is sometimes built between boxes is good because it lets you check for mites on drone pupae as you pull it apart, and the intact burr comb gives bees a ladder to climb from box to box. He doesn't cut out swarm cells, instead doing his best to prevent swarms naturally, then splitting hives to raise new queens if he misses the boat and swarm cells do materialize. He also doesn't scrape off propolis, since he believes this processed bee sap kills pathogenic bacteria and viruses in the hive.

Michael Bush's goal is

two-pronged --- he wants to raise bees that don't need chemicals to

stay alive, and he wants his apiary to be as little work as

possible. Those sound like laudable permaculture ambitions to me.

| This post is part of our The Practical Beekeeper lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our neighbor's bees have been

busy stealing honey from our two hive boxes, so we decided it's time to

build a 5 gallon bucket honey strainer.

The food grade buckets are

more expensive, but worth it for a project like this.

Stay tuned for a full report

on how this method works for straining out the wax.

When I first read about oilseed

radishes, the only

negative report claimed that the cover crop stinks to high heaven when

rotting in the spring. I haven't noticed any odor at all from my

decaying oilseed radishes, but their dead bodies do catch the eye with

their striking poses.

Once

they rot just a bit more than is shown in the two photos above, the

radishes also catch the attention of the local worms. I broke one

radish in half and was surprised to see this earthworm tunneling

through the decaying center.

Once

they rot just a bit more than is shown in the two photos above, the

radishes also catch the attention of the local worms. I broke one

radish in half and was surprised to see this earthworm tunneling

through the decaying center.

Worm action is probably

the reason these huge roots disappear into the soil so quickly.

I'll be able to plant into these beds without raking much of anything

to the side in just a few weeks, and the soil will be improved by up to

a quarter of a pound of dry organic matter per square foot --- not a

bad yield for tossing down a couple of cents' worth of seeds last fall.

In nature, a healthy, mature

hive tries to swarm at least once every year. As soon as the

first flowers open, the bees scurry to gather nectar and pollen, which

tempts the queen to lay a lot of eggs and to hatch out plenty more

workers. At a certain point, the hive is getting crowded, and the

bees start filling up the brood nest (where eggs are usually laid) with

honey and pollen. These two conditions --- lots of bees in a

small space and a brood nest full of food --- change something in the

hive mentality, and they decide it's time to make some new queens.

In nature, a healthy, mature

hive tries to swarm at least once every year. As soon as the

first flowers open, the bees scurry to gather nectar and pollen, which

tempts the queen to lay a lot of eggs and to hatch out plenty more

workers. At a certain point, the hive is getting crowded, and the

bees start filling up the brood nest (where eggs are usually laid) with

honey and pollen. These two conditions --- lots of bees in a

small space and a brood nest full of food --- change something in the

hive mentality, and they decide it's time to make some new queens.

Once queen larvae are

developing in the hive, the old queen knows it's time to move on.

She gathers up about 60% of her workers and flies away to another nest

site, leaving the rest of the workers behind to care for the developing

queens. Eventually, the new queens hatch, and one usually kills

off the others before settling in as a new matriarch of the old hive.

From the perspective of

a bee, swarming is an effective method of reproduction. In

addition, the gap in brood rearing between when the old queen leaves

and when the new queen starts to lay tends to break many disease cycles

in the old hive. However, beekeepers generally want to prevent

swarming since a hive that swarms rarely produces much honey.

Swarm prevention begins with

keeping the brood nest from becoming congested during the first nectar

flow. Michael Bush adds supers as necessary so the bees have

plenty of room to dehydrate nectar. However, supering alone is

not enough, so he also opens up the brood chamber by putting one empty

frame after every two frames of brood. A different beekeeper,

Walt Wright, uses a less invasive method called checkerboarding, which

consists of alternating frames of capped honey with drawn (but empty)

frames in the box above the brood nest.

Swarm prevention begins with

keeping the brood nest from becoming congested during the first nectar

flow. Michael Bush adds supers as necessary so the bees have

plenty of room to dehydrate nectar. However, supering alone is

not enough, so he also opens up the brood chamber by putting one empty

frame after every two frames of brood. A different beekeeper,

Walt Wright, uses a less invasive method called checkerboarding, which

consists of alternating frames of capped honey with drawn (but empty)

frames in the box above the brood nest.

If you didn't get around

to managing the hive and you see queen cups already built, you'll have

to move on to the second phase of swarm prevention. No, don't cut

out those queen cups --- once the bees have decided to swarm, they'll

just build them again. Instead, take each frame with a queen cup

on it and start a "nuc" --- a small, new hive --- with an extra frame

of honey to tide the bees over. More tomorrow on how to handle

nucs, but for now just understand that each of these little hives can

be raised into a new hive to expand your apiary. As long as you

open up the brood  nest at the same time you

create the nucs, the bees should think they've already swarmed and will

get back to work making honey for your larder.

nest at the same time you

create the nucs, the bees should think they've already swarmed and will

get back to work making honey for your larder.

The flip side of the

swarming coin is that the behavior creates an opportunity for

beekeepers to get started with no outlay of cash. This spring, I

may follow Bush's advice and ask police and rescue dispatchers and the

local extension agent to contact me when they hear about swarms.

More on how to catch a swarm when I've put some of my readings into

practice.

| This post is part of our The Practical Beekeeper lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Drilling holes in a bucket

from the outside presented a problem.

Plastic hanging chads.

Sanding them off while

reaching into the 5

gallon bucket honey strainer is awkward. I wished I had tried to

drill the holes from the inside now, it may have made the clean up

process easier.

My friend Heather has been

giving me great editing feedback on my

book, and she

brought up an interesting point in response to my chapter about scavenging

biomass.

Heather asked:

My friend Heather has been

giving me great editing feedback on my

book, and she

brought up an interesting point in response to my chapter about scavenging

biomass.

Heather asked:

When we go camping on the eastern shore there are all these signs about not bringing in firewood from certain counties because the wood might carry in different bugs.

I'm sure it's OK because you do it, but why is it OK? Are there things that people shouldn't do in terms of moving around biomass so they don't spread / introduce pests?

Despite Heather's belief that I can do no wrong, she's got an excellent point, and one I hadn't even considered in the context of the garden. Many states prohibit you from moving firewood far (often limiting transport to 50 miles or less) since invasive diseases and insects can come along for the ride and infect areas that used to be safe from their depradations. I can see how moving tree leaves from place to place might present a lower but still real risk.

In general, I've read that

you shouldn't worry much if you're moving biomass ten miles or less

since an insect might fly that far on its own on a gusty day.

And, of course, processed biomass like cardboard or coffee grounds are

unlikely to host pests.

In general, I've read that

you shouldn't worry much if you're moving biomass ten miles or less

since an insect might fly that far on its own on a gusty day.

And, of course, processed biomass like cardboard or coffee grounds are

unlikely to host pests.I'm also careful, when gathering leaves, to steer clear of areas with invasive herbaceous species, since I don't want seeds of garlic mustard or Japanese stilt grass to germinate in my garden. This problem is probably less thorny, though, since even the most lackadaisical gardener is likely to notice invasive plants before they can make their way into adjacent woodland.

What would you add to those warnings?

Our chicken waterer provides clean water for day

old chicks, broody hens, and your main flock.

One of the main thrusts

of Michael Bush's book is --- backyard beekeepers of every experience

level need to be breeding homegrown bees. With diseases and pests

wiping out colonies left and right, we can't risk narrowing the gene

pool by letting a few big companies breed all of our queens, and we

shouldn't even use our single favorite queen as the mother of every new

hive in our apiary. Meanwhile, we should try to include the

survivor genetics of feral bees, letting our queens mate with wild

drones and allowing queens of captured swarms to maintain control of

their colonies.

But the reproduction of bee

hives is quite complex, as my swarming post probably made

clear. Do we need fancy equipment and a PhD to raise our own

queens? Although Michael Bush does go into some production

methods that felt beyond me, he also mentioned very simple breeding

techniques for those of us who aren't obsessed with maximum

productivity.

But the reproduction of bee

hives is quite complex, as my swarming post probably made

clear. Do we need fancy equipment and a PhD to raise our own

queens? Although Michael Bush does go into some production

methods that felt beyond me, he also mentioned very simple breeding

techniques for those of us who aren't obsessed with maximum

productivity.

Remember how I split my

hive this past spring?

Splitting by the box (one full box of brood in each daughter hive) is

indeed the easiest way to double your number of hives with very little

work. If you put ten deep frames or sixteen medium frames of

brood and honey in each daughter hive, both hives will take off so

quickly that you might be able to split the hives again before the year

is out. Those of you with several hives can take a single frame

of brood and a frame of honey from each of your strong hives and create

a new hive in this manner without setting the parent hives back much at

all.

Smaller

splits are handy for raising queens --- a useful technique for the more

advanced apiarist who wants to replace ornery or failing queens with

daughter queens from a stronger and nicer hive. For these splits,

Bush recommends having some nucs on hand. Nucs are smaller boxes

--- often just big enough to hold two, three, four, or five frames ---

that keep the workload down for small colonies of bees. You might

put one frame of brood and one frame of honey in a two frame nuc, then

add the tiny colony to a queenless hive once the nuc has raised a

queen. Alternatively, you could put three frames of brood and two

frames of honey in a five frame nuc, then transfer the new colony to a

normal sized brood box to create a new hive once the queen is laying.

Smaller

splits are handy for raising queens --- a useful technique for the more

advanced apiarist who wants to replace ornery or failing queens with

daughter queens from a stronger and nicer hive. For these splits,

Bush recommends having some nucs on hand. Nucs are smaller boxes

--- often just big enough to hold two, three, four, or five frames ---

that keep the workload down for small colonies of bees. You might

put one frame of brood and one frame of honey in a two frame nuc, then

add the tiny colony to a queenless hive once the nuc has raised a

queen. Alternatively, you could put three frames of brood and two

frames of honey in a five frame nuc, then transfer the new colony to a

normal sized brood box to create a new hive once the queen is laying.

When's the best time to

split? Beekeepers have a saying that you can either produce lots

of new hives, or make lots of honey, but not both. If you split

hives before the main nectar flow, the bees can use all those blooms to

create a strong colony that will make it through the winter with no

help from you...but you probably won't be able to harvest any

honey. On the other hand, if you let the parent hive collect lots

of honey during the main nectar flow, then split them, you might end up

having to feed the daughter hives to make sure they have enough winter

stores. As with any other part of beekeeping, you have to decide

how much to focus on the health of the bees, and how much to focus on

your own stomach.

| This post is part of our The Practical Beekeeper lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Our friendly, neighborhood

hardware store sharpens dull tools free of charge.

I've never asked the people

at Home Depot or Lowes for this kind of extra service,

but something tells me their store policy would frown on any activity

that produced such a high volume of sparks.

Buying a grinder would cost

somewhere between 50 and 200 dollars, but beware of the steep learning

curve. If you don't do it right you could ruin a good axe or sword.

Last year, I stumbled through

learning

to incubate eggs to

produce homegrown chicks, so this year I'm ready to put my newfound

knowledge into practice. And to experiment some more, of course.

Last year, I stumbled through

learning

to incubate eggs to

produce homegrown chicks, so this year I'm ready to put my newfound

knowledge into practice. And to experiment some more, of course.

One thing we learned is

to go ahead and start chicks at the right time of year rather than

waiting and hoping that a broody hen will decide to sit on some

eggs. I have high hopes that our Cuckoo Marans will feel

motherly...eventually...but since the pasture will be at its peak in

April, May, and June, I want to have our first chicks struggling out of

their shells at the beginning of March.

I put 21 eggs in the

incubator, which is as many as will fit laying down on their sides for

hatch. Since that left a bit of room when the eggs sit upright

for the first 19 days, I added newspaper spacers in the center of the

incubator, where hatch

rates have historically been lower.

Mark your calendars for

fluffy cuteness around March 3!

A month ago, I wrote, "If

editing takes much longer, we'll have

to go back [to Bays

Mountain] for another round of nature meditation."

A month ago, I wrote, "If

editing takes much longer, we'll have

to go back [to Bays

Mountain] for another round of nature meditation."

Editing did take much longer. In fact, I've still got two thirds

of my fourth (and final) polishing round to go before I can give the

manuscript to my publisher.

(Yes, I know it is a little overly obsessive to go through four drafts

before I even give the manuscript to the official editor. There's

something about the permanency of a print book that makes me leery of

letting the least tiny problem slide. On the plus side, the final

product should be something I'm actively proud of.)

Meanwhile, Bays Mountain gave

me a very interesting thought problem to take my mind off the

book.

Meanwhile, Bays Mountain gave

me a very interesting thought problem to take my mind off the

book.

See the dangling tree on

the right side of the photo above? Clearly a beaver had gnawed it

off its feet, but the stump is nowhere to be found. We could see

down to the bottom of the little pond, and there's no pointy stump

beneath its waters, nor is there one anywhere within a ten foot radius.

Any ideas on how a

beaver-gnawed log came to be suspended in the air?

You know you're pushing the golf cart's limits when icicles grow on the

underside between trips.

With lows around 10 last night, the hauling opportunity seemed too good

to pass up.

A frozen driveway allowed us to bring in a week's worth of firewood, 15

bags of leaves for mulch, some chicken

waterer supplies, and a month's worth of chicken feed.

Maybe tomorrow the driveway will stay frozen long enough that we can

haul some straw?

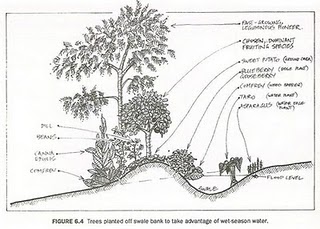

I read a lot of blogs and

books that talk about water management. The problem is, they're

all tailored toward arid climates, where you need to work hard to

capture any rain that falls and store it in your soil for later dearths.

I read a lot of blogs and

books that talk about water management. The problem is, they're

all tailored toward arid climates, where you need to work hard to

capture any rain that falls and store it in your soil for later dearths.

Our water management

issues are very different. The badly eroded soil of the forest

garden becomes so waterlogged that algae grows in puddles even during

the winter. Our gutterless trailer pours so much water off the

sides that the soil is sodden, and simple foot traffic is enough to

turn the ground into a morass.

Meanwhile, our two

creeks are clearly eroding more than they should. The big creek

was straightened by some foolish farmer a few decades ago, and even

though I know channeling it back into its original meander would slow

the flow, I'm afraid to undertake such a huge project.

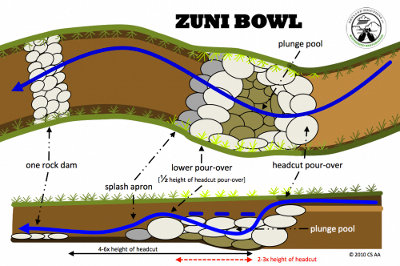

The

smaller creek has dug itself so deep that that the lower portion has

vegetationless banks four feet tall. As I was gathering leaves in

the woods, I noticed that the tree that had been holding back the

advance of the headcut was losing the battle.

The

smaller creek has dug itself so deep that that the lower portion has

vegetationless banks four feet tall. As I was gathering leaves in

the woods, I noticed that the tree that had been holding back the

advance of the headcut was losing the battle.

I suspect all of these

problems are really opportunities if considered from a permaculture

standpoint. I've been raising up the forest garden with

hugelkultur mounds, and the rotting wood releases enough water a bit at

a time that I was

able to grow tomatoes there without irrigating last summer. Gutters on the East

Wing would clear up the worst path morass, channeling the water into

one of our IBC tanks to allow us to experiment

with aquaponics. Maybe the small creek could be mended with a Zuni

bowl and some homemade

meanders. And

one of these days I'd like to create a little pond.

But I don't want to dive into

any water management project without a bit more information. Do

you have any books you would recommend for permaculture style water

management in wet landscapes? I'm looking for an inspiring print

source that shows how to work with water on a small scale with no heavy

machinery. (You can recommend websites too, but I'm unlikely to

read them deeply --- I have a mental block against getting in depth

information off the internet.)

But I don't want to dive into

any water management project without a bit more information. Do

you have any books you would recommend for permaculture style water

management in wet landscapes? I'm looking for an inspiring print

source that shows how to work with water on a small scale with no heavy

machinery. (You can recommend websites too, but I'm unlikely to

read them deeply --- I have a mental block against getting in depth

information off the internet.)

I'm

pushing to finish

editing the paper version of Weekend Homesteader, so there's no lunchtime

series this week. However, I don't want you to go into

withdrawal, so I'm giving away Weekend

Homesteader: October

today and tomorrow over on Amazon. Just follow the link and

you'll be able to download it completely free.

I'm

pushing to finish

editing the paper version of Weekend Homesteader, so there's no lunchtime

series this week. However, I don't want you to go into

withdrawal, so I'm giving away Weekend

Homesteader: October

today and tomorrow over on Amazon. Just follow the link and

you'll be able to download it completely free.

Despite the fact that

the four exercises in Weekend Homesteader: October are geared toward

the fall, they're actually quite timely in February. I walk you

through making quick hoops, which are perfect for preheating late

winter soil so you can plant sooner. And I also write about

free biomass, storage vegetables, and living simply.

As always, if you don't

want to mess with Kindle format, you can email

me and I'll reply

with a free pdf copy. And please do tell any friends who might be

interested! I gave away 8,875 free copies of Weekend Homesteader:

August a few weeks ago and would love to beat that record.

We figured out today that

stacking straw in a vertical fashion on the golf cart allows us

to haul six bales compared to horizontal stacking that only gave us

four.

We made some progress with

our second coconut flour experiment, but we haven't figured it all the

way out yet. Mark had watched a

youtube video that showed how to extract coconut butter by drying

the meat and passing it through a juicer, so we started our experiment

by whirring the coconut meat up in the food processor, then letting it

dry out in the food dehydrator for about eight hours.

We made some progress with

our second coconut flour experiment, but we haven't figured it all the

way out yet. Mark had watched a

youtube video that showed how to extract coconut butter by drying

the meat and passing it through a juicer, so we started our experiment

by whirring the coconut meat up in the food processor, then letting it

dry out in the food dehydrator for about eight hours.

I suspect we made a

mistake when we turned off the dehydrator before supper and didn't get

to the juicing stage until a couple of hours later. In

retrospect, I think the dehydrating step wasn't meant to dry out the

coconut so much as warm it so the oils would flow better. Perhaps

that's why the juicer was only able to extract a moderate amount of oil

from the coconut meat.

I didn't think the

de-juiced coconut meat was fine enough to bake with, so I passed the

fragments through the MagicMill on its most coarse setting.

Unfortunately, there were still enough oils left in the meat that the

coconut flour gunked up the machine, just

like last time.

Clearly, we need to figure out the extracting step better before we put

the remains through the mill.

I can tell we're making

progress, though. Look --- coconut butter separated from

something vaguely resembling coconut flour!

Anna and I came to a

Valentine's Day agreement when we started dating.

That first year I asked

"Which would you prefer, a heart shaped box of chocolate, a dozen

roses, or a nice dinner somewhere semi-fancy?"

She thought about it a bit

and said "A heart shaped box implies chocolate should only be for

special occasions, and I need chocolate almost every day. I cringe at

cut flowers and prefer to enjoy them in the ground, and dinner out on a

holiday sounds too crowded for my comfort level."

I was more than relieved to

hear such a practical answer. We decided to start skipping the holiday

and agreed that every day felt like Valentine's Day when you live in

paradise with someone you love.

We managed to haul in another

golf cart load of straw this morning before the ground thawed out.

Turns out you can squeeze on 7 bales if you ratchet strap one to the

back like in the photo above.

Mark is the type of

considerate husband who doesn't post details on the internet when his

wife wrecks the golf cart. So I have to tell you myself.

Mark is the type of

considerate husband who doesn't post details on the internet when his

wife wrecks the golf cart. So I have to tell you myself.

Remember how icicles

were forming on the underside of the golf cart as we hauled in supplies

Sunday? They also started affecting the "gas" pedal. I

didn't realize that was the case until I went to turn the golf cart

around and reversed right through my berry patch, shrieking in terror

the whole way.

It turns out that when

the "gas" pedal sticks in the on position, slamming your foot on the

brakes does absolutely nothing. Yes, I did manage to halfway tear

down one of our  chicken pasture gates at the

same time. Mark considers it an unusual day when I don't break

something and ask him to fix it --- this wasn't an unusual day.

chicken pasture gates at the

same time. Mark considers it an unusual day when I don't break

something and ask him to fix it --- this wasn't an unusual day.

For future reference, if

you drive your golf cart through a creek repeatedly when the

temperature is in the teens, a big lump of ice will form around the

"gas" pedal mechanism. This makes the pedal stick in the on

position, but you can work around it by getting in the habit of pushing

the pedal, then slipping your foot underneath and pulling the pedal

back to "off." If you get really good, you can also push the

"gas" pedal very lightly and have it freeze halfway down, setting the

golf cart on cruise control at a moderate pace.

I drove like that for three

trips on Sunday and one on Monday, but then my fun came to an abrupt

end. After unloading the golf cart, I headed inside to get a

drink of water, and when I came back out, pressing the "gas" pedal did

nothing. I thought I'd really broken the golf cart that time, and

I could see Mark's dreams of an ATV coming to fruition. Luckily,

when the afternoon sun melted the lump of ice around the pedal

mechanism, the golf cart sprang back to life and she was able to haul

one more load of straw Tuesday morning before the floodplain thawed so

much as to become impassable. I love our alternative farm truck!

I drove like that for three

trips on Sunday and one on Monday, but then my fun came to an abrupt

end. After unloading the golf cart, I headed inside to get a

drink of water, and when I came back out, pressing the "gas" pedal did

nothing. I thought I'd really broken the golf cart that time, and

I could see Mark's dreams of an ATV coming to fruition. Luckily,

when the afternoon sun melted the lump of ice around the pedal

mechanism, the golf cart sprang back to life and she was able to haul

one more load of straw Tuesday morning before the floodplain thawed so

much as to become impassable. I love our alternative farm truck!

(As a final note, will

someone please tell me what the "gas" pedal is called in an electric

vehicle?")

I'm ready to pronounce this plastic,

temporary fence experiment a success.

The put up and take down

procedure is easy and quick.

We've been using this type

of material for a few years now. I remember first getting it during

the 2008 election. There's no sign of U.V. damage yet. I'd guess it

might be another 10 years before we start seeing signs of drying and

cracking. I'll let you know in 2022 if it's still the cat's meow of the

temporary fence world.

We've been using this type

of material for a few years now. I remember first getting it during

the 2008 election. There's no sign of U.V. damage yet. I'd guess it

might be another 10 years before we start seeing signs of drying and

cracking. I'll let you know in 2022 if it's still the cat's meow of the

temporary fence world.

One downside to this material

is the chewability factor. It takes Lucy about a minute to bite her way

through if she really wants to, and thinks nobody is looking. She's

usually a good dog, but has a serious bad girl streak to her when it

comes to kitchen scraps meant for the flock.

Despite the relative

mildness of this winter, the soil

temperature (and

thus the spring garden) is actually a smidge behind last year's

conditions. I suspect that last winter's heavy coat of snow

insulated the soil surface, and that this year's clouds worked in the

opposite direction to make the soil colder than it normally would have

been.

No matter what the

cause, I only planted my first unprotected garden seeds yesterday ---

breadseed poppies. I would normally have planted some early peas

too, but the earth hasn't warmed to 40 degrees yet, so there's no

reason to let my seeds rot in the ground.

Despite the cold spell

this past weekend, lettuce is up and running under the quick

hoops --- I hope to

be able to pick some in two or three weeks. Meanwhile, the onions

I seeded inside came up thickly. About the same time I'm picking

the first spring lettuce, I'll be teasing the seedlings apart and

setting them out in their final garden home.

Why did we choose an electric

golf cart over a gas powered ATV?

We had an old Isuzu 4 wheel

drive truck that may have been in the saddest shape any truck has ever

been in. It was only 400 dollars, and we were short on cash at

the time and thought we could nurse it back to being a decent farm

truck. The problem was our location. Being new in town made it

difficult to coax a mechanic to make a house call, which is what was

needed when the truck broke down in the middle of the driveway.

The country was still

recovering from Hurricane Katrina and fuel prices were reaching record

levels. It felt like we had to get ready for a future where gas would

cost as much or more than what folks in Europe were paying. Maybe I was

reading too much information on Peak Oil speculation. I'm not sure what

to believe when it comes to that subject amymore, and in retrospect the

decision may have been partially based on a fear of running out of

petrol.

I realize if gas prices go

through the roof then electric rates would more than likely follow, but

the plan was to do what several people on the internet were doing which

was to use solar cells to charge the golf cart.

Another deciding factor was Anna's

comfort level. I was pretty sure the golf cart would be less

intimidating than driving a truck through troubled waters mixed with a

bit of dirt.

Another deciding factor was Anna's

comfort level. I was pretty sure the golf cart would be less

intimidating than driving a truck through troubled waters mixed with a

bit of dirt.

It may have been more

practical to choose an ATV, but sometimes the path less traveled

yields the greatest rewards.

The manuscript of Weekend

Homesteader is officially done. (Well, until my editor sends

me revisions to look at.) Depending on my technical prowess, the

files will either be winding their way to New York via the internet

today, or taking the slower mail approach on a CD.

The manuscript of Weekend

Homesteader is officially done. (Well, until my editor sends

me revisions to look at.) Depending on my technical prowess, the

files will either be winding their way to New York via the internet

today, or taking the slower mail approach on a CD.

Here are the highlights

of the finished product:

- Days before the actual deadline: 13

- Days after my virtual deadline: 17

- Sleepless nights due to excitement: 5

- Meltdowns due to terror: 2

- Suggested word count from my editor: 60,000 to 150,000

- Final word count: 105,745

- Number of times I read each of those words: 4

- How many times too may was that: 1

- Maximum number of images my editor said I could have: 200

- Number of images I'm sending her: 229

- Most boring part: editing the index the second time

- Most exciting part: adding lots of cool sidebars while imagining proto-Annas propagating their own mushroom spawn on cardboard or using urine to fertilize the garden

- How bored my blog readers are with hearing me natter on about it: I don't know --- you tell me.

Phew! If you asked

me today if I wanted to write another book, I'd say no. But I

suspect by next month I'll already be dreaming about the other ten

projects in my idea notebook.

If you're just tuning

in, you can download the second

drafts of the first ten months on Amazon. Weekend Homesteader:

March is coming out next week, and there will be no Weekend

Homesteader: April since the last few projects are intangibles I

scattered through other months in the print book. The print book will be a full color paperback due out in the fall.

Thanks for bearing with

me!

We decided today was the day to stop ignoring the tangled mess of bent

metal that was once our workshop.

The job called for a hex key

bit, but the closest thing I could find today was a star bit that

seemed to do the job until I stripped out the teeth of the bit.

Taking the main legs apart

along with a few sections of the roof was all it took to make it more

manageable. The metal pieces have a nice powder coating to them, which

might come in handy for a yet unknown future project.

My favorite material for

blocking sunlight and weeds at the bottom of a kill

mulch is cardboard, so I was thrilled when a friend told me he was

getting rid of a lot of cardboard boxes. I've been carrying in

about ten from the parking area each morning when I walk Lucy, but I

used up a whole weeks' worth in about half an hour Friday. That

sent me hunting for other kill mulch bases.

My favorite material for

blocking sunlight and weeds at the bottom of a kill

mulch is cardboard, so I was thrilled when a friend told me he was

getting rid of a lot of cardboard boxes. I've been carrying in

about ten from the parking area each morning when I walk Lucy, but I

used up a whole weeks' worth in about half an hour Friday. That

sent me hunting for other kill mulch bases.

Egg cartons seem to have

a lot of potential in a certain niche. If you open them out, the

bottom half of one carton overlaps the top half of another carton quite

well, although the  seam between rows is less

secure. I wouldn't want to use egg cartons as a kill mulch if

there were really ornery weeds underneath since the plants would

certainly find that gap.

seam between rows is less

secure. I wouldn't want to use egg cartons as a kill mulch if

there were really ornery weeds underneath since the plants would

certainly find that gap.

That said, I have a

feeling that the cups of the egg carton might capture and hold water,

helping it infiltrate the soil rather than running off. My gut

says that fungi will also like the extra air space left behind when I

top the egg cartons off with mulch. As with my bark kill

mulch, I'll be

waiting to see how the experimental weed blocker works as the growing

season progresses.

A piece of heavy nylon rope

tied in just the right configuration is how our roofers carried the 14

foot sections of tin for the barn roof today.

Soon after posting that our

soil was too cold for peas, I stuck the thermometer in

the ground again and got a reading of 39 degrees. Yes, that's

still one degree shy of their minimum germination temperature, but the

ten day forecast (with the exception of today) promises highs in the

fifties to sixties and lows above freezing, so I figured I could risk

it.

Soon after posting that our

soil was too cold for peas, I stuck the thermometer in

the ground again and got a reading of 39 degrees. Yes, that's

still one degree shy of their minimum germination temperature, but the

ten day forecast (with the exception of today) promises highs in the

fifties to sixties and lows above freezing, so I figured I could risk

it.

I've posted before about

how I make my pea

trellises.

These light-weight fence posts combined with the green

plastic trellis material are easy to put up and take

down and look quite elegant in the garden. I do most of the work

myself, but always need to ask Mark to pound in the fence posts.

I've only had two

problems with my pea plantings in recent years. I've learned not

to plant peas in the waterlogged soil of the back garden since they

tend to get root rot. And this year I'm also working harder to

keep all of the soil except for the row where the peas will come up

completely mulched. Last year, weeds grew amid the pea plants

before I pulled the mulch back into place, and when I tried to rip the

weeds out, I removed a few pea vines as well. Luckily, the

partially decomposed straw that mulched the beds over the winter is in

just the right state to sit politely in the middle of the bed without

blowing around and covering up emerging seedlings.

As a final note, if

you're a raw beginner, you might want to check out my posts about soaking

peas, giving extra

soaked peas to the chickens, why

we no longer grow shelling peas, and growing

peas for tendrils.

I'm looking forward to sugar snap peas in May!

Yesterday we helped Joey

build this mini chicken coop.

It went together pretty fast.

That's an old plastic cargo carrier for the roof.

I think the scrap cabinet

panels give it a nice touch of class.

I'll admit that I've wondered

whether hiring someone to

replace the barn roof was a shortcut we shouldn't take, but after

watching the crew of three work from dawn to dusk Saturday, I'm ready

to admit that hiring pros made sense.

I'll admit that I've wondered

whether hiring someone to

replace the barn roof was a shortcut we shouldn't take, but after

watching the crew of three work from dawn to dusk Saturday, I'm ready

to admit that hiring pros made sense.

Within half an hour of

reaching the farm, they'd torn about half the tin off the south side of

the barn and were getting ready to haul

in the first round of roofing panels. I'm pretty sure this

half hour of labor would have taken me and Mark all day if we'd done it

ourselves.

The boss --- Tony --- is

not only a pro, he also has a gentle way of talking to both his crew

and the barn owners that set us all at ease. If you're local and

need a major job done, let me know and I'll give you Tony's phone

number --- we highly recommend him.

We also really appreciated

the roofers' safety conscious attitude. Mark explained to Tony

right off the bat that we don't have homeowners' insurance. (We

don't have anything valuable enough to insure.) As I brought Tony

a check for the first quarter of his

fee, I overheard him

reminding the crew about safety and telling them to wear their

harnesses at all times.

We also really appreciated

the roofers' safety conscious attitude. Mark explained to Tony

right off the bat that we don't have homeowners' insurance. (We

don't have anything valuable enough to insure.) As I brought Tony

a check for the first quarter of his

fee, I overheard him

reminding the crew about safety and telling them to wear their

harnesses at all times.

We felt so confident in

their abilities that we left after a few hours to spend the day building

my brother's chicken coop. When we came home, it

looked like no one had even sustained a scratch. Then Tony called

down from the roof to ask me to check inside Lucy's mouth. "I

think she might have something stuck there," he explained.

Sure enough, Lucy's

relentless chewing had lodged a stick across the bridge of her mouth

where she couldn't paw it out, and Tony had been able to spare enough

attention from the roof to notice. He'd actually tried to pry it

out too, but Lucy didn't trust him quite enough to let him do the

deed. Mark and I teamed up on her and made short work of the

offending stick. What other roofer adds "dog baby-sitter" to

their job title?

Sure enough, Lucy's

relentless chewing had lodged a stick across the bridge of her mouth

where she couldn't paw it out, and Tony had been able to spare enough

attention from the roof to notice. He'd actually tried to pry it

out too, but Lucy didn't trust him quite enough to let him do the

deed. Mark and I teamed up on her and made short work of the

offending stick. What other roofer adds "dog baby-sitter" to

their job title?

Before:

And after:

They've still got about

two days of work ahead of them to hit the more problematic back side of