Underground house orientation

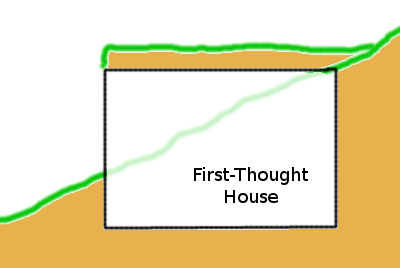

One of the biggest

differences between Mike Oehler's underground house and many other

designs is that he faces his buildings uphill. While houses

opening downhill have a better view (and better potential for passive

solar gain if you choose the right hillside), Oehler concluded they

also have poor drainage, ventilation, and light. In addition,

this type of building (which he calls a "First-Thought House") has to

be shored up very carefully since the weight of the hillside above is

constantly pushing down on the structure. Finally, First-Thought

Houses generally have doors only on one side of the structure, which

can be a fire hazard.

One of the biggest

differences between Mike Oehler's underground house and many other

designs is that he faces his buildings uphill. While houses

opening downhill have a better view (and better potential for passive

solar gain if you choose the right hillside), Oehler concluded they

also have poor drainage, ventilation, and light. In addition,

this type of building (which he calls a "First-Thought House") has to

be shored up very carefully since the weight of the hillside above is

constantly pushing down on the structure. Finally, First-Thought

Houses generally have doors only on one side of the structure, which

can be a fire hazard.

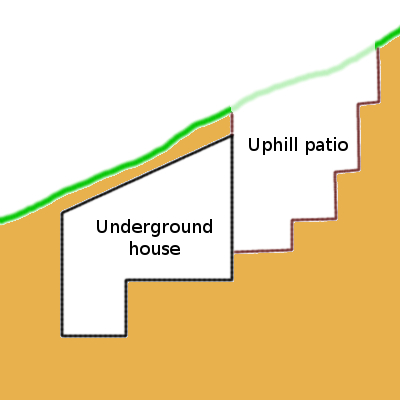

In contrast, Oehler's

buildings are bright, sunny and well-ventilated inside due to his

unique design. In addition to digging out the house itself, he

also excavates an uphill patio, which sucks up moisture flowing down

the hill, holds back the hillside with terraces (that are easier to

replace than walls of a house), and provides a shady garden area right

outside the front door. Then Oehler adds in an excavation for a

side door (not shown in this diagram), which brings in light and air

from the other side of the structure. There's much more to the

design than this, so you'll obviously want to check out the book if you

want to give the technique a try, but this is the gist.

In contrast, Oehler's

buildings are bright, sunny and well-ventilated inside due to his

unique design. In addition to digging out the house itself, he

also excavates an uphill patio, which sucks up moisture flowing down

the hill, holds back the hillside with terraces (that are easier to

replace than walls of a house), and provides a shady garden area right

outside the front door. Then Oehler adds in an excavation for a

side door (not shown in this diagram), which brings in light and air

from the other side of the structure. There's much more to the

design than this, so you'll obviously want to check out the book if you

want to give the technique a try, but this is the gist.

My caveats in the

last post have much

more to do with Oehler's construction methods (which I'll mention in

later posts) than with the design (which I find fascinating). On

the other hand, I'm not so sure I see how his design promotes better

drainage --- it looks to me like water running down the hillside would

pool right at the front door (where Oehler adds French drains to move

water around to the back). Wouldn't you get better drainage from

a First-Thought House, especially if you slant the roof down toward the

front?

| This post is part of our The $50 and Up Underground House Book

lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Assuming the "first thought" house is excavated to around 2 meters below the groundwater level, you would have 1/5 of a bar of water pressure on the bottom of the wall facing the hill. Not to mention the pressure from the earth on the hillside itself.

The house with the uphill patio doesn't have both problems assuming there is sufficient drainage. For your house to stay dry you have to pull the local water table in the patio down to below the patio ground level.

by building into the side of a hill, you're automatically above the ground water level. In the diagram of the first thought house, if the ground water level were even with the label, for instance, then the front edge of the house would necessarily be at the edge of a lake.

With the patio house, that patio would serve as a resevoir for moisture flowing down the hill, and the terrace would serve to block sunlight. it would seem that both the contentions that this would be a brighter, dryer house must be false.

I'm planning on building an underground house: it'll be basically a basement with the front side exposed and no house above it.

Hey Anna not sure if you have seen this blog, but if not you might be interested in there underground house and journey. http://mikeandlisaworld.blogspot.com/p/our-off-grid-story.html

Beware it sucks you in with hours of entertainment.

Tracy

@doc: the water table follows the contour of the landscape to some extent. If the water table on a hill were horizontal, the top of a hill would lack water and thus plants.

So on a hillside the water table will follow the incline. How well it follows the surface depends on things like permeability and character of the soil, drainage and precipitation. Some soils will act more like spunge and retain water. Flow through a porous medium is usually relatively slow compared to flow in a stream.

Perhaps I didn't express my self well. Let's not confuse water table with drainage flow pattern after a rainfall. When you dig a well (or a basement), it fills with water when, and only when, you get below the level of the water table. In a topographical cross section, surface water exists wherever the land level falls below the water table level.

Most vegetation does not reach its roots down to the water table.

One can excavate a terrace in the side of a hill, build a house, then back fill three sides with appropriate drain tiling and cleverly slope the roof and cover it with earth to optimize drainage of rainfall around and away from the house.

Perhaps I don't understand the author's "reverse orientation." It seems to me that he's just asking for flooding problems on the patio at the front door. But then, "dog bites man" is not news. If he didn;t have a new angle, nobody would need to publish the book.

@doc: The water level of a well that is in use is lower than the water table. Otherwise there wouldn't be any flow towards the well.

Here you can see typical flow times of water through the soil. It's slower than people generally realize.

I think the most important thing is getting as much sun in as possible in winter. The first thought house could get full sun (if entrance north oriented) But the Oehler design would get virtually no low winter sun in (even when entrance north oriented)

Roland: the diagram in your citation is an exaggeration of scale and only remotely accurate if the distance between the well site and the stream is on the order of miles. If the well & stream are, say, a few hundred feet apart, then the water level in the well and that of the stream are virtually the same, as is the table level in between them.

Having dug a few holes and built more than a few basements, I can assure you that the back of your basement dug into a hill will not be into the water table if the front is not. And if the front is, then you're already standing in water when you start digging.