Two grafts for beginners

When it comes right down to

it, you really only need to know two methods to graft most young fruit

trees. The whip and tongue graft is the simplest, appropriate for

young apple and pear trees grafted onto rootstock the same

pencil-thickness as the scionwood. Budding is used if you have

very little scionwood to go arond or if you need to graft a cherry,

plum, apricot, or peach, none of which are reputed to respond well to

whip and tongue grafting. Budding is also less sensitive to the

scionwood and rootstock having different diameters.

When it comes right down to

it, you really only need to know two methods to graft most young fruit

trees. The whip and tongue graft is the simplest, appropriate for

young apple and pear trees grafted onto rootstock the same

pencil-thickness as the scionwood. Budding is used if you have

very little scionwood to go arond or if you need to graft a cherry,

plum, apricot, or peach, none of which are reputed to respond well to

whip and tongue grafting. Budding is also less sensitive to the

scionwood and rootstock having different diameters.

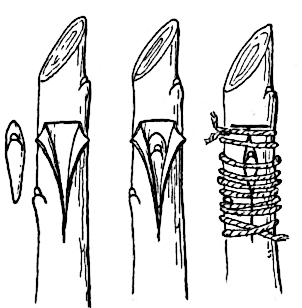

A whip and tongue graft

joins the scionwood to the top of the rootstock using a slanting cut to

increase surface area and a notch (the tongue) to help the two pieces

stay in place as you tie them. Select a point about four to eight

inches above the ground on the rootstock, where the diameters of the

two pieces of wood match, then make a cut six times the diameter of the

wood (says Garner), or roughly an inch and a

half long (says Phillips). You'll want to

practice until you can make a cut with no bulges or raggedness, then

focus on lining up the tips and the cambium all around so that there's

an 80% visual match. Add the tongue (a 1/8 inch cut into each

piece of wood), then trim the scion to two buds before slipping the

joints together.

After making the cuts for a

whip and tongue graft, you'll want to wrap the new tree with some kind

of binding

material to hold the junction firmly in place. Start at the

bottom and leave space between loops as you circle up to ensure you

haven't gotten the pieces out of alignment, then cover everything up by

taping back down over the junction. Add some sealant on the tip

and over the tape and then plant your new tree out in a garden bed for

the first year. In early June, the buds on the scionwood should

have sprouted and the longest should be at least two to four inches

long; that's your cue to pinch the tips of all but the best shoot and

to remove any rootstock growth.

After making the cuts for a

whip and tongue graft, you'll want to wrap the new tree with some kind

of binding

material to hold the junction firmly in place. Start at the

bottom and leave space between loops as you circle up to ensure you

haven't gotten the pieces out of alignment, then cover everything up by

taping back down over the junction. Add some sealant on the tip

and over the tape and then plant your new tree out in a garden bed for

the first year. In early June, the buds on the scionwood should

have sprouted and the longest should be at least two to four inches

long; that's your cue to pinch the tips of all but the best shoot and

to remove any rootstock growth.

These instructions

assume you're followed the American trend of bench grafting (which

simply means you dug up rootstocks and took them inside to graft), in

which case you probably joined your rootstock and scionwood between

December and March. If grafting onto a rootstock in the field,

you'll want to wait until the week before the first green shows on the

buds so that winter's cold won't damage the new union.

In contrast, bud

grafting is generally completed in the summer, between June and early

August. There are many types of bud grafts, but shield budding is

most common. First, prepare the rootstock by making a T-shaped

series of slits in its bark, then slide in a carefully  prepared bud shield.

The bud comes from the leaf axil of the current season's growth and

consists of the bud and the leaf stem. After slipping the piece

of scionwood under the rootstock's bark (with the bud itself sticking

out), you tie the two together and seal the wound, but don't cut off

the top of the rootstock yet. Instead, you let the bud heal into

the young tree, sometimes waiting until the next year to tempt the

scionwood to grow. Once it's time to force the bud, slowly remove

leafy shoots of the rootsock a few at a time, or bend down the top of

the stock so the scion bud is the highest one on a curved stem.

After the bud begins to grow well, you can cut off the top of the

rootstock so the scionwood takes its place.

prepared bud shield.

The bud comes from the leaf axil of the current season's growth and

consists of the bud and the leaf stem. After slipping the piece

of scionwood under the rootstock's bark (with the bud itself sticking

out), you tie the two together and seal the wound, but don't cut off

the top of the rootstock yet. Instead, you let the bud heal into

the young tree, sometimes waiting until the next year to tempt the

scionwood to grow. Once it's time to force the bud, slowly remove

leafy shoots of the rootsock a few at a time, or bend down the top of

the stock so the scion bud is the highest one on a curved stem.

After the bud begins to grow well, you can cut off the top of the

rootstock so the scionwood takes its place.

I've used whip and

tongue grafting before and found it relatively simple, but haven't

tried budding yet. How about you? Are there other grafting

techniques you recommend for the beginner?

| This post is part of our Grafting lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Nichole --- Glad it helped! Scionwood can keep for several weeks, or even months, as long as it's stored in a cool, damp place (like a root cellar). People regularly take it in January or February for grafting in March and April.

There's quite a vibrant community of scionwood swappers who send the wood through the mail, and I've had good luck with that too. Here's my most recent post about how to mail scionwood. Good luck!