The positive effects of agriculture

The

results of the Neolithic

Revolution were

striking. On the positive side, a

farmer was able to grow more food than he needed to feed his family, so

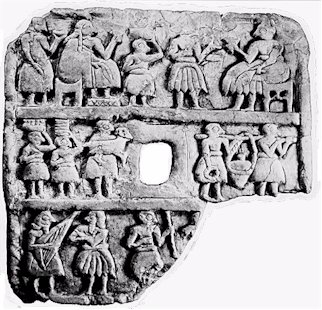

for the first time in human history we saw specialization.

Agricultural societies were able to support leaders, artists,

craftsmen, priests, scribes, and soldiers, none of whom had to worry

much about where their food came from.

The

results of the Neolithic

Revolution were

striking. On the positive side, a

farmer was able to grow more food than he needed to feed his family, so

for the first time in human history we saw specialization.

Agricultural societies were able to support leaders, artists,

craftsmen, priests, scribes, and soldiers, none of whom had to worry

much about where their food came from.

We also had time to

create

new tools and technologies. The first example of writing sprang

up in

the Fertile Crescent, probably as a method of recording information

about ownership and production of land. In fact, you can follow

the trail of agriculture all the way to present, tracing the

domestication of wheat, maize, and rice foward to most of humanity's

most striking

accomplishments.

Agriculture basically

created civilization as we know it. In fact, using

anthropologists' definition of civilization, farming was a prerequisite

for civilization in every part of the world. This is the

explanation you'll see in most modern history texts --- doesn't it

sound a bit like a revisionist history? "Look, the people with

agriculture won! Let's say that agriculture created civilization."

This post is part of our History of Agriculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries:

|

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Almost by definition history is written by the winners. According to your reasoning that would make "revisionist history" a pleonasm.

A more widespread view, I think, is to call a history revisionist when it descibes fact verifiably different. Like e.g. calling Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge a paradise on earth.

There are still some hunter-gatherer tribes in remote parts of out planet to this day. To the best of my knowledge (and admitting that I could very well be wrong since I'm not an anthropologist), none of them have advanced much beyond the level of your own hunter-gatherer ancestors.

It seems to me that hunter/gatherers need to move regularly (maybe even seasonally) to prevent overexhaustion of local resources. If you have to be able to carry all your stuff (even with a travois), that doesn't leave room for most of the trappings of civilization. To me that indicates strongly that to develop skills beyond the hunter-gatherer stage, you need to put down roots.

Actually, as you'll see in later posts, the early farmers worked hard to wipe out their hunter-gatherer competition. We should probably look at modern hunter-gatherer tribes as a bit like the American Indians on reservations in the U.S. --- they're struggling to get by in areas that can barely support human life, often being forced to use techniques that aren't their ancestral techniques. No wonder they don't make Toyotas. In the past, many hunter-gatherer tribes actually weren't nomadic, especially those that depended more on ocean life or nomadic fish like the salmon. And they hadn't been relegated to areas barely fit for human habitation.

I think that the issue of civilization (which isn't one I'm really going to delve into in this lunchtime series) is a lot like the issue of intelligence. In my Animal Behavior class in college, I vividly remember my professor pointing out that saying "No animal is an intelligent as a human" is an error in understanding. Intelligence (and, I would argue, civilization) is too complex to be measured on a single IQ scale. Even within humans, IQ isn't a realistic indicator of overall intelligence --- there are people who show amazing social skills or astonishing ability to manipulate electronics but don't have high IQs. I guess what I was getting at with my last throwaway line is that we are measuring cilivization as being a society like ours, when we should instead be looking at a broader idea of what civilization could be.

Alas, coming up with a good question doesn't imply I have an adequate answer. But I'll give it a try.

But I'll give it a try.

First though, I didn't say it had to be one metric. Second, I'd stress the words "objective criteria" to rule out value judgements.

In science, one should always define the citeria which would indicate success before running an experiment.

Most important, I think that a successful civilization should take good care of its members. This could be measured from e.g. lifespans and causes of death and signs of diseases. Things like these can be quantified from acheological evidence. Also important is how it deals with crises. In case of draught, digging wells or a canal to a lake is more effective than building temples or sacrifices.

On the other hand, I've got the feeling that the boundaries we see between civilizations aren't as solid and clear as we think they are. In the real world things tend to be fuzzy. And on historical timescales things are always in motion, and it is hard to form a complete picture about how people lived in the distant past.

It is an established fact that animals and humans evolved. I think there is ample evidence that civilizations adapt to change and evolve as well. For if they don't adapt, they disappear. So how well a civilization adapts is another measure of it's success.

Since civilizations with agriculture became dominant, it must have bequeathed a decisive advantage. And that is not a value judgement, but follows from the facts.

That's it for now. It's way past my bedtime.

I like those metrics, but I would add something to your measure of taking good care of the civilization's members beyond lifespan, cause of death, and signs of disease. Something like how happy its members are, although that gets into sticky, value judgment territory. Still, I think that a society where the common guy is pretty much a slave isn't doing a good job even if the slave is healthy.

I think that there are two ways of looking at how well a civilization is doing --- the straight evolutionary take and a more humanitarian take. An evolutionary take would say that a civilization is a success if it lasts a long time and spreads, regardless of how well the individual people in that civilization fare. But I think that in measuring human civilizations, we have to consider a more humanitarian measure too, one which takes into account inequalities, suffering, etc.