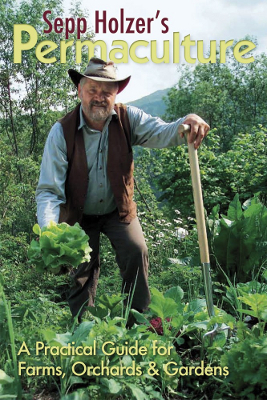

Sepp Holzer's Permaculture

Sepp

Holzer's Permaculture is a book that I recommend

checking out of the library, but probably not buying unless you happen

to live in high elevation Europe or have an obsession with heavy

machinery.

Sepp

Holzer's Permaculture is a book that I recommend

checking out of the library, but probably not buying unless you happen

to live in high elevation Europe or have an obsession with heavy

machinery.

Sepp Holzer writes about

techniques he uses on his 111 acre farm (the Krameterhof), which sits

around 5,000 feet above sea level on the southern slope of the

Schwarzenberg Mountain in Austria. Throughout the book, Holzer

brags about what he can grow at such a high elevation, but from a U.S.

perspective, it's not so unique --- I'm pretty sure he lives in the

equivalent of zone 5 (one zone colder than us).

What I enjoyed most

about the book is the way Holzer developed his own type of permaculture

based on youthful experiments imitating natural cycles. He

started farming in 1962 at the age of 19, and only learned about the

permaculture movement in 1995, but he was practicing permaculture long

before that. As a result, Holzer's book is full of permaculture  techniques you won't find

anywhere else --- he's not simply regurgitating Mollison's ideas (or

anyone else's). On the down side, some of the illustrations in

the book seem to represent flights of fancy that Holzer hasn't yet put

into practice, so be sure to take the non-photographic ramblings with a

grain of salt.

techniques you won't find

anywhere else --- he's not simply regurgitating Mollison's ideas (or

anyone else's). On the down side, some of the illustrations in

the book seem to represent flights of fancy that Holzer hasn't yet put

into practice, so be sure to take the non-photographic ramblings with a

grain of salt.

The other problem I had

with Holzer's book is his obsession with moving lots of earth

around. Yes, his terraces, ponds, hugelkultur mounds (simply called "raised beds"

in the book), humus storage ditches (aka dry

weather swales), and

underground shelters are useful and pretty, but they aren't very

appropriate to small scale permaculturalists who don't happen to have

an excavator at their beck and call. That said, it was easy to

find four topics in his book applicable to the backyard (or at least

the small scale farm), which I'll regale you with this week at

lunchtime.

| This post is part of our Sepp Holzer's Permaculture lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

Anna: I seeded a carboard food take-out (clam shell) container with onion seeds. This morning I was moving it to the green house when the clam shell container folded shut (will cut the 2 halves apart in the future).

I carefully removed what I figured was the dirt and sprouts that fell on top of the other sprouts. Brought them in the house and spent the next HOUR carefully transplanting each delicat onion sprount into 2 big containers. I misted the sprouts often to keep their little tails from drying out.

Do you think these transplanted sprouts will have a 50/50 chance of growing up? I am leaving the others out in the green house and letting them fight to survive the avalanch that just happened in their life. Ha! Ha!

Why not use an excavator if your land stretches out over 1200 feet of elevation like Mr. Holzer's does? It doesn't mean you'd have to buy one. You can easily rent them. And it is basically a one-time expense. Trying to do with a spade what an excavator can do in a day would take depressingly long, I suspect.

Austria has been a cultured landscape for centuries if not milennia. So even on mountains such as the Schwarzenberg there are adequate access roads. Just look at the pictures on his website. The winter 2006 pictures are especially nice.

If you look at the pictures taken from the air comparing his land to that of his neighbours, the difference is stunning.

I'm not saying you should never use heavy machinery, but his use turned me off for a couple of reasons. First, even if it's entirely appropriate for his property, the techniques are much harder to bring to the small-scale, which is what most backyard permaculture readers are going to be trying to do.

Second, I question why he needs to turn his entire property into an agricultural area. If his goal is just to make a living off the land, I suspect he could have done that in a third the area or less, then let the more remote regions return to wild forest. He does mark about a fifth of the property as wilderness on his map, but I think we should tithe much more land area than that to nature. Using heavy machinery makes it so easy to access formerly unaccessible spots that we end up pushing nature to the sidelines. The great thing about hand tools is that they hold us back to only cultivating what we really need to.

From what I can tell, his goal is to be an educator (and a tinkerer, I can sympathize with that ) rather than a homesteader. His piece of land looks a lot nicer than the rather barren surroundings.

) rather than a homesteader. His piece of land looks a lot nicer than the rather barren surroundings.

With regard to your last point, lack of power tools seems a poor substitute for common sense. People were doing stupid things long before power tools existed.

First thanks for the review of the book. I wondered if Sepp did anything smaller scale after viewing his videos. Guess not!

Re: what you said: "He does mark about a fifth of the property as wilderness on his map, but I think we should tithe much more land area than that to nature."

I don't know if he goes over this in his book, but I've seen a video where he talks about the "natural" landscape of his home being pines with shallow soil that causes lots of flood problems. I can't remember whether or not the pines were a result of humans or not. Anyway, it was my understanding that his cultivation was to show that another option was available than pines that nurture more and more acidic soil.

Roland --- I agree with you about his goal, and I totally agree that it can be tough to put limits on your projects when you're experimenting. But it still seems a little extreme to need to terrascape nearly a hundred acres....

(See below about the neighboring properties.)

Chris --- I haven't read his other English Book "Rebel Farmer", so there might be smaller scale stuff in there. (It's less available because I believe it's out of print.)

From this book, I think that the neighboring landscape is all pine plantations, a bit like you'll find in the US Deep South. So the aerial photos Roland saw weren't comparing native woodland to Holzer's property --- they were comparing a pine monoculture. I don't have anything good to say about pine plantations, and I'm positive Holzer's property is ten times more biologically active than that!

Please don't take this as a knock on your homesteading adventures... just wanted to point out that there's more than one way to skin a proverbial cat! If everyone lived on 50 acres, sure, maybe I'd agree that you'd farm a couple of those acres and wild the rest. But most people live in cities, to which food must be trucked from farms, which must produce food for many more people than live on the farm. If you're only subsisting, you're not farming -- and you're little better off than the African subsistence farmers who grace the pages of National Geographic.

Also, the rest of the USA, let alone the planet, is not climactically identical to Virginia. Out here in the arid West (Colorado), a "small family farm" typically runs over a thousand acres; multiply that by 5 for Montana and Wyoming. I have spent time on farms larger than 50 square miles. The climate dictates larger spreads for nominal production, and land area to be worked dictates the use of heavy equipment for almost any task.

Let's not forget that in ancient times, geo-engineering projects were accomplished with human labor -- often thousands of slaves. They built dams, aqueducts, terraces -- massive earthmoving and construction projects. However, being that today it's more difficult to find a reliable source of slaves than it is to hire an excavator or a bulldozer,...

Point being, you scale down from Holzer. I scale up. Way up. Just one of our clients can heal more land and sequester more carbon than a thousand suburbanites with backyard chicken coops. The sooner we can replace millions of acres of sterile, chemical-warfare monoculture with Krameterhofs, the better. Think big!