Rabenberg on brix

"Brix" is one of those terms

tossed around by folks in alternative agriculture circles that I

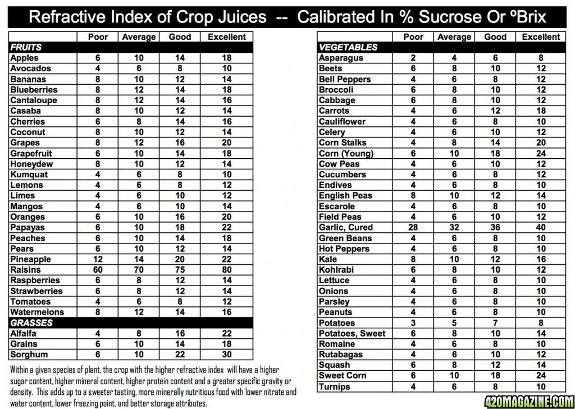

considered a little kooky in the past. The idea is simple --- you

use a meter to determine the percent by weight sugar in a plant, which

gives you a rough estimate of the nutritional quality of the food since

more nutritious crops are usually also sweeter.

"Brix" is one of those terms

tossed around by folks in alternative agriculture circles that I

considered a little kooky in the past. The idea is simple --- you

use a meter to determine the percent by weight sugar in a plant, which

gives you a rough estimate of the nutritional quality of the food since

more nutritious crops are usually also sweeter.

Even though I agree with

the theory behind brix, I used to roll my eyes at the

implementation. I can taste the difference in brix between my

homegrown vegetables and the ones in the grocery store, so why buy a

$100 meter?

Glen Rabenberg's talk on

"Improving crop quality using readily available tools" helped me

realize that my understanding of brix in the garden is overly

simplistic. He doesn't just check the brix of crops being

harvested; he monitors plants at various stages of their life span to

prevent disease and insect problems.

Rabenberg asserts that at

increasing levels of brix, farms become healthier in a holistic

fashion. Disease fungi and thrive at a brix below 7, but when the

leaves of a plant reach a brix of around 10 to 11, Rabenberg sees

drought resistance in the crops and fewer weeds nearby. At 13 to

14, he begins to see resistance to pest insects. Having recently

seen in a scientific source that the fire blight

bacteria are deterred by high levels of sugar in pear nectar, I'm willing to believe that

there's some truth to Rabenberg's ideas.

Rabenberg asserts that at

increasing levels of brix, farms become healthier in a holistic

fashion. Disease fungi and thrive at a brix below 7, but when the

leaves of a plant reach a brix of around 10 to 11, Rabenberg sees

drought resistance in the crops and fewer weeds nearby. At 13 to

14, he begins to see resistance to pest insects. Having recently

seen in a scientific source that the fire blight

bacteria are deterred by high levels of sugar in pear nectar, I'm willing to believe that

there's some truth to Rabenberg's ideas.

So, how do you raise the

brix of your food? As with plant

secondary metabolites,

the key is balanced soil. Rabenberg believes that most soil

problems can be remedied by focusing on five minerals --- calcium,

phosphorus, and (to a lesser extent) potassium, magnesium, and

sulfur. If Rabenberg sees low brix, he performs a soil test and

usually adds calcium and/or phosphorus on the theory that a more

nourished plant will produce more sugar and be more resistant to

problems. In his experience, potassium is actually often too

high, leading to weed problems --- if that's the case, you need to

round out your fertilizing campaign to prevent a buildup of the

important, but easy to overdo, nutrient.

I know I've said "asserts"

and "believes" a lot of times in this post --- it's not because I don't

think Rabenberg is on the right track. However, I want to read up

more on the topic before I take his word as gospel, and suggest you do

too. Still, perhaps Rabenberg is right and I need to start

collecting data on the brix levels of our crops (and on the electrical

conductivity of our soil, a topic which will have to be its own post at

a later date). Perhaps if I noticed when tomato plants were

most at risk, I could head blights off at the pass?

I know I've said "asserts"

and "believes" a lot of times in this post --- it's not because I don't

think Rabenberg is on the right track. However, I want to read up

more on the topic before I take his word as gospel, and suggest you do

too. Still, perhaps Rabenberg is right and I need to start

collecting data on the brix levels of our crops (and on the electrical

conductivity of our soil, a topic which will have to be its own post at

a later date). Perhaps if I noticed when tomato plants were

most at risk, I could head blights off at the pass?

Find out how to test your soil and

interpret the results in Weekend

Homesteader.

| This post is part of our ACRES conference lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.