Plants for spring and fall grazing

The rest of this week's

lunchtime series is an overview of forage plants that match the three

pasture seasons --- spring/fall (this post), summer, and winter.

You should keep in mind that specifics like this are very location

specific, so if you live in the Deep South or in another area where

warm season (rather than cool season) grasses dominate, you should take

everything I write with several grains of salt. The closer you

live to Gene Logsdon's home base in northern Ohio, the more likely his

suggestions are to fit your pasture like a glove.

The rest of this week's

lunchtime series is an overview of forage plants that match the three

pasture seasons --- spring/fall (this post), summer, and winter.

You should keep in mind that specifics like this are very location

specific, so if you live in the Deep South or in another area where

warm season (rather than cool season) grasses dominate, you should take

everything I write with several grains of salt. The closer you

live to Gene Logsdon's home base in northern Ohio, the more likely his

suggestions are to fit your pasture like a glove.

In Logsdon's (and our)

location, spring is when pasture plants are at their peak, with a

lesser peak ocurring in the fall. You'll plan your meat animals

to match these peaks and (if your operation is big enough) will also

use the extra growth to make hay (or stockpiled

grass) for the

winter. So what do you plant in those spring/fall paddocks?

Logsdon makes a good case for

not planting at all. His experience (and mine) has been that if

you open up the tree canopy and mow close to the ground regularly, bluegrass will eventually dominate

your pastures. You might or might not need to plant the white

clover that works

so well to round out the pasture polyculture.

Logsdon makes a good case for

not planting at all. His experience (and mine) has been that if

you open up the tree canopy and mow close to the ground regularly, bluegrass will eventually dominate

your pastures. You might or might not need to plant the white

clover that works

so well to round out the pasture polyculture.

A less permanent

alternative is to plant ryegrass in the place of the

bluegrass that springs up naturally. Ryegrass is a bit taller

than bluegrass, so it may shade out your white clover (unless you seed

specially formulated clover varieties that can handle the more

aggressive grass), and even the perennial ryegrass versions need to be

reseeded at intervals. On the other hand, ryegrass might make up

for the extra effort since it produces more dry matter per acre than

bluegrass does and establishes quickly. Both bluegrass and

ryegrass are among the most palatable grasses in most livestocks'

estimation, but ryegrass

is often infected with an endophyte.

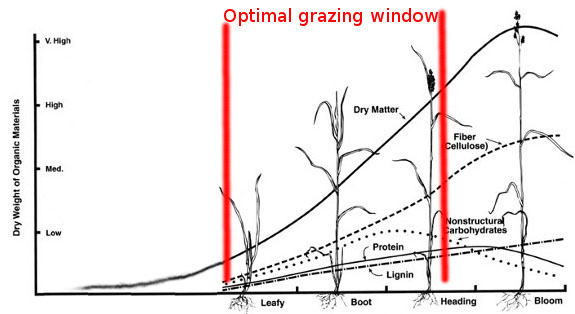

Ryegrass and bluegrass are

managed about the same. As I learned the hard way last year, you

need to graze or mow them hard and repeatedly in the spring and early

summer so they don't go to seed, since fruit production makes the

grasses less palatable and slows their growth considerably. You

can graze the pasture down to one inch, then let the grass regrow to

four to six inches before turning your animals back in. This

happens pretty quickly in the spring, and is one of the advantages of

short grasses.

Ryegrass and bluegrass are

managed about the same. As I learned the hard way last year, you

need to graze or mow them hard and repeatedly in the spring and early

summer so they don't go to seed, since fruit production makes the

grasses less palatable and slows their growth considerably. You

can graze the pasture down to one inch, then let the grass regrow to

four to six inches before turning your animals back in. This

happens pretty quickly in the spring, and is one of the advantages of

short grasses.

Drought, more than heat,

is what prevents bluegrass and ryegrass from barreling on through the

summer, so Logsdon suggests that it might be worth your while to

irrigate your pastures to keep them productive. I noticed that

the paddocks directly downhill from my oft-watered vegetable garden did

much better last summer than grasses in other areas.

Although bluegrass and

ryegrass aren't really winter grasses, you can let them grow in the

fall to stockpile forage for the winter. Logsdon notes that the

dense root structure of the bluegrass/clover sod prevents major damage

when smaller livestock are turned into the pasture in wet weather, and

he finds that the disturbed soil in hoofprints actually helps clover

gain more of a foothold. Stay tuned for later posts detailing

summer and winter alternatives to the bluegrass/clover pasture.

| This post is part of our All Flesh is Grass lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

I feel so lucky that you do all this amazing analysis that I can put into practice someday. On another note, I might try to root some cuttings of the American Holly bush that sits in front of our cabin and try that for a living fence/hedge. It's native to our area, quick to grow, easy to prune/manicure, and the birds enjoy the berries. Fencing in the animal areas is probably impractical, but I thought it might work well as a future garden perimeter.

~ Mitsy

Mitsy --- I look forward to seeing the results of your experimentation as well once you're on the farm! It's great to have people experimenting in the same climate zone as you....

You'll have to let me know how it goes if you try the holly hedge.