Planning a high density apple orchard

I enjoyed reading the varied

responses to my

post introducing high density apple orchard techniques, so I thought you'd like to

follow along as I lay out my experiment. Here are the first few

decisions I had to make:

I enjoyed reading the varied

responses to my

post introducing high density apple orchard techniques, so I thought you'd like to

follow along as I lay out my experiment. Here are the first few

decisions I had to make:

Do I

want to use an industrial-type, apple-planting system? Unless you're willing

to commit time every month to playing with your trees, you might be

better off trying something else. Other options for diversifying

your backyard orchard exist, such as espaliers and fruit

cocktail trees, and

if you just want lots of apples with little work, a semi-standard tree

is the way to go. But if your goal is to grow lots of apples in a

small space, and you are willing to put in the effort to win those

rewards, one of these industrially tested systems may work well for you.

Which

kind of high density system should I choose? There are perhaps a

dozen different systems that let you cram lots of apples into a small

space, and each one is managed a little differently. The systems

that put the trees closest together (such as the super spindle) cost

more per acre to begin with since you have to buy a lot more trees and

trellising, but many industry analysts suggest super spindle orchards

also bring in the most profit by the eighth year because apple yields

are higher. Those of us growing trees in the backyard are

probably less concerned about economics and more concerned with

cramming as many varieties as possible into a small space without

committing to an excessive amount of maintenance. I eventually

settled on the tall spindle system as best for most backyard growers

since it combines nearly as high yields as the super spindle with less

fidgety maintenance. (I'll make a post on maintenance later ---

this one's just about designing the planting.)

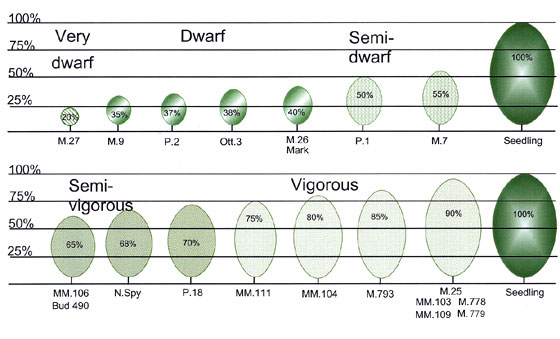

What

kind of rootstock should I choose? Experts suggest G.41,

(aka Geneva 41), G.11, G.935, M.9 (aka Malling 9), M.9T337, or Bud.9

(aka Budagovsky 9). These are all extremely dwarfing rootstocks,

so if you're planting a less vigorous apple variety, the next step up

(like M.26) might be better. Keep in mind that choosing one of

these ultra-dwarfing rootstocks means it's going to be mandatory for

you to keep your trees completely weeded, mulched, and watered at all

times, so if you're going to be neglectful, you might want to follow one

of our readers' suggestion and plant a semi-standard

tree, then use pruning and training to keep the apple's size

down. I'm going to include a few semi-standard trees in my

planting to allow me to compare and contrast with the dwarfs, but I

chose Bud.9 for most of my rootstocks.

How

close together should I plant the trees? Depending on which

expert you talk to (and which high density system you're using), trees

should be spaced two to nine feet apart, in rows that are ten to

fourteen feet separate. This

calculator is a

great way to get an  idea of proper spacing based

on your specific conditions --- I think that three feet is going to be

about the right distance between trees in each row in my garden.

Meanwhile, the recommended between-row spacing should be taken with a

grain of salt if you're squishing these dwarf apples into your home

garden since the distance is really meant to prevent shading of the

next row over. So I felt quite comfortable leaving a mere four

foot aisle between my new tall spindle apple bed and a bed used for

perennial propagation since new cuttings prefer moderate shade.

idea of proper spacing based

on your specific conditions --- I think that three feet is going to be

about the right distance between trees in each row in my garden.

Meanwhile, the recommended between-row spacing should be taken with a

grain of salt if you're squishing these dwarf apples into your home

garden since the distance is really meant to prevent shading of the

next row over. So I felt quite comfortable leaving a mere four

foot aisle between my new tall spindle apple bed and a bed used for

perennial propagation since new cuttings prefer moderate shade.

How

do I prepare for my trees? I laid down a kill

mulch of cardboard covered by well-rotted wood chips to prepare for

late fall planting of my dwarf apple trees. The mulched row will

be about three feet wide, then we'll mow the grassy aisles just like in

our vegetable garden. The one big difference between starting a

high-density apple row and a vegetable row is that I'm going to have to

erect some kind of support for the dwarf trees before they arrive ---

either a ten foot tall stake for each one or a trellis --- and will lay

out an irrigation system now so watering doesn't get away from me in

the spring.

How many trees should I plant? Experts suggest you

may get 15 to 20 apples per tree the second year, 50 to 60 the third

year, 100 apples the fourth year, and a bushel the fifth year if you

start with well-feathered trees. ("Well-feathered" refers to

whether the tree has small branches --- experts on high-density apple

plantings recommend selecting a tree at least 5/8 inch in diameter and

5 feet tall with 10 to 15 feathers less than a foot long, all above 30

inches off the ground.) So take a look at how many apples your

family consumes, how well the varieties you've selected keep, and how

ripening times are scattered across the year when deciding how many

trees to order. (Don't forget to factor in other

fruits ripening up on your homestead too!)

How many trees should I plant? Experts suggest you

may get 15 to 20 apples per tree the second year, 50 to 60 the third

year, 100 apples the fourth year, and a bushel the fifth year if you

start with well-feathered trees. ("Well-feathered" refers to

whether the tree has small branches --- experts on high-density apple

plantings recommend selecting a tree at least 5/8 inch in diameter and

5 feet tall with 10 to 15 feathers less than a foot long, all above 30

inches off the ground.) So take a look at how many apples your

family consumes, how well the varieties you've selected keep, and how

ripening times are scattered across the year when deciding how many

trees to order. (Don't forget to factor in other

fruits ripening up on your homestead too!)

The only other tidbit I

considered when planning my experimental tall spindle orchard was

comparisons to normal apple trees. I'm curious to discover

whether the ultra-dwarfing rootstocks will be able to find enough

micronutrients to keep apple flavor at its peak, so I'm including a

couple of varieties in my planting that I already have growing as

semi-standard trees in the forest garden. Once they're all

bearing, we'll conduct some side-by-side taste tests.

But that's a long

experiment in the future. Stay tuned for another post about

training and pruning, an essential component of a high density apple

planting, coming up soon.

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

If your interested in knowing: Bud 9 is a nice rootstock. It produces a nice eating apple aswell. Light pinkishy flesh, balanced sweet/acid. It can take the heat well like m111. I have had some fungal issues with it in the summer though. I only use it to test new varieties though. All of my Bud 9 trees are actually grown in 7 gallon pots, because it doesn't do well in the sand.

And because of its lineage including some of the Eurasian crab apples, it is good for pollinating. It has multiple bloom times in a season too in warmer areas, so it can be there for the latter flowering varieties.

I don't have much of a choice in what I can use as a rootstock in my area. I have tried every one I could get my hands on. Nothing stands up to the M111. 20 foot tree, to a 5 foot tree, it has the versatility and adaptability. Apple borers will destroy a tree. I deal with them year round. Very few rootstocks can take them. None of my dwarf trees did, they would normally drop the scion. The only 2 I use are Bud 9 and M111. I'm waiting to get hold of some of the new Israeli rootstocks, but that wont be for a few more years or so. For now M111 is what I recommend and prefer, and what I sell all my trees on. I only use Bud 9 because it would make a tire grow apples. Even if only a couple. All of my seedling wood is grafted onto it, and it easily makes it fruit the third year, if not the second.

Imo, Outside of a commercial orchard setting, or a pot, its one of the biggest mistakes to be made, putting apples on dwarf roots. Most backyard growers don't want a full size tree so buy a dwarf. Then they wonder what they're doing wrong when their apple doesn't thrive. Nurseries charge more for the trees, but don't explain that they need more care, making up for the lack of pruning they need.

I get all this from hands on experience, in case anyone wonders where my pennies worth comes from. Ive grown apples in central Florida for almost 10 years. No mean feat.:)

T, I'm very much looking forward to the side by side comparison of our semi-standard trees pruned to dwarf size versus those grown on Bud 9. I'm also going to try to remember to ask my local apple nursery guy what kind of rootstock he uses with his trees. They've done extremely well (not pruned to be dwarfs, though) in even the poorest soil parts of our yard.

We haven't had trouble with borers, although I've read about them. Our main issue at the moment seems to be cedar apple rust --- fungi generally get us on a lot of our crops.

I really appreciate benefiting from your extensive experience!

Hello Sir How would I order M25 apple trees I have 3 acre land 6500 feet above see level I live in kashmir India Thank-you