Pasture ecology

At its best, management

intensive grazing mimics the ecology of a native prairie. Quick

bursts of heavy grazing result in pastures that are extremely diverse,

often hosting up to 30 plant species. Trees and shrubs don't have

a chance to get a foothold the way they do in pastures that are

continuously grazing with low numbers of animals, and the grasses and

legumes produce a lot more leaves than they do when you're grazing

continuously with lots of animals. From an animal's point of

view, the result is much higher quality forage and a lot more of it.

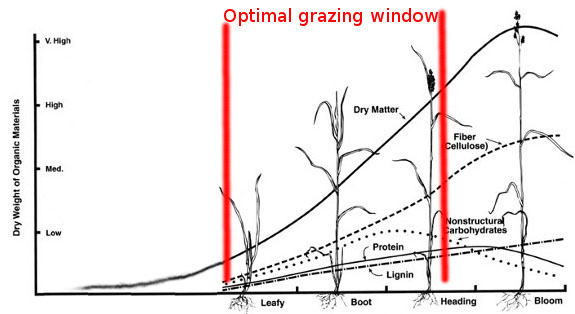

The image above shows

how putting animals on your pasture only during the optimal grazing

window produces the maximum amount of forage of the highest nutritional

value. The far left side of the graph shows what happens if grass

is grazed nearly down to the ground --- at first, the plant grows

very slowly because it has to use up stored energy in its roots to

create new leaves. As the leaf area becomes large

enough to grab energy straight from the sun, the plant grows faster and

faster. But then the plant decides to flower, so it slows down

leafy

growth in order to push some energy toward blooming. After a

certain

point, the plant isn't making any extra leaves at all because it has

gone to seed.

To get the most from your

pasture, you must keep your plants between the two stages marked with

red lines in the

diagram. You never graze the pasture so low that the grasses have

to pull too much

energy from their roots and you never let them get so tall that they

start to bloom. For poultry, sheep, goats, and pigs, you should

let

the grass grow until it's 3 to 4 inches tall, then graze it down to 1

to 2 inches tall before repeating the cycle.

To get the most from your

pasture, you must keep your plants between the two stages marked with

red lines in the

diagram. You never graze the pasture so low that the grasses have

to pull too much

energy from their roots and you never let them get so tall that they

start to bloom. For poultry, sheep, goats, and pigs, you should

let

the grass grow until it's 3 to 4 inches tall, then graze it down to 1

to 2 inches tall before repeating the cycle.

Bill Murphy has

experimented with various methods of renovating poor pastures, and has

discovered that well-timed bouts of grazing of the sort outlined above

are just as effective as costly campaigns of killing the existing sod

and seeding new pastures, overseeding with clover, or alternating

pastures with row crops. Keeping the nitrogen content of the soil

down and the grass grazed low enough favors clovers, and they seem to

spring up on their own to fill in more and more of the pasture sward

every year. That means richer and richer forage for your grazing

animals to eat.

| This post is part of our Greener Pastures on Your Side of the Fence

lunchtime series.

Read all of the entries: |

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

That picture of cattle grazing looks like a herd of White Faced Hereford. The breed my grandmother used to keep. For more on Herfords, I found this page informative http://www.ansi.okstate.edu/breeds/cattle/hereford/

Looking forward to the rest of this series on pasture.