Our first swarm

I was weeding the mule garden

about 15 feet away from the hive when the bees decided to swarm, but I

missed the mass flight. I had walked off to the barn to get

another tool, and when I returned I heard a great buzzing overhead and

to my left. By the time I got my eyes turned around, the bees

were out of sight.

I was weeding the mule garden

about 15 feet away from the hive when the bees decided to swarm, but I

missed the mass flight. I had walked off to the barn to get

another tool, and when I returned I heard a great buzzing overhead and

to my left. By the time I got my eyes turned around, the bees

were out of sight.

Luckily, they hadn't

flown far. In fact, they'd settled into the honeysuckle on the

exact same sassafras last

year's absconded package settled on before flying away.

That means the bees would have been right beside our top-bar-hive-turned-swarm-trap...but I had talked Mark into

helping me move that structure behind the barn the day before.

Oops.

We were woefully

unprepared for a swarm, despite the fact that I've been blogging about

little else all week. I really should have known it was coming,

not just because this is the swarming time of year, but also because

the Warre hive's three boxes were getting pretty congested.

I took the top two

photos up through the screened bottom the morning before the swarm

left, catching the back (left) and front (right) of the hive, and it

was evident that the cluster of bees was humongous at that time.

That's why the second photo is out of focus --- the bees were hanging

all the way down to the floor. The hive had been a bit like this

(although not quite so extremely crowded) for a couple of weeks, and if

I'd wanted to slow down swarming behavior, that would have been a good

time to nadir a fourth body into my

hive.

However, I didn't have

the spare equipment on hand because the place I ordered from is swamped

and hadn't mailed my hive bodies two weeks after I paid for them.

(I haven't figured out how to make top bars yet, so I couldn't just

make my own homemade hives.) We do have a fourth hive body, but

I'd been saving that box in case the package

shows up before the new hive parts do. Which is all a long

explanation for why I let the bees get so congested that they swarmed

before they need to have. All of that said, Warre theory is that

you want your bees to swarm to break the pest and disease cycle, so all

I would have been doing with management is slowing down the swarm, not

preventing it.

(As a side note, it's

interesting to compare the inside of the original hive the morning

before (top photos) and the afternoon after the swarm (bottom

photos). The comparison gives you an idea of how much of the

hive's population leaves with the swarm and how much stays home to tend

the worker brood and baby queens. Generally, about 10,000 workers

and drones (two-thirds of the population) leave, but they're soon

replaced by workers hatching out in the old hive.)

Anyhow, mea culpa's

aside, I had a swarm on my hands and I didn't want to lose it. My

first hope was that the bees would find my swarm trap even though the

structure was now a couple of hundred feet away, but I soon discovered

that the bees were considering another site instead. How could I

tell? Well, I've spent the last week reading Honeybee

Democracy (which I'll review here after finishing the last couple

of chapters), and thus had discovered a lot about the behavior of bees

in swarms.

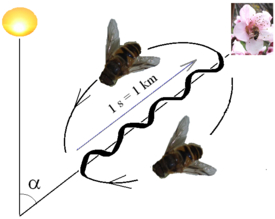

It turns out that after

a swarm leaves the hive, they always settle just like mine did, not far

from the parent hive. At that point, an astonishing exercise in

consensus decision-making occurs. Most of the bees hang out

around the queen, but 300 to 500 workers peel off to survey the

surrounding 30 square miles in search of nest sites. If a worker

finds a potential home, she returns to the swarm and performs a waggle

dance (shown below) to inform her cohorts of the location. Other

bees go and check it out, dancing about the site if they like it or

ignoring it if they don't, and eventually enough bees have settled on

one location that the swarm figures they've found what they're looking

for. At that point, they all take off and relocate to their new

home.

This all sounds a bit

esoteric, but the truth is that once you have a swarm in front of you,

waggle dances are extremely obvious and easy to decipher. After

only a few seconds of observation, I was able to find two workers

dancing about the same location, which I videoed above. The

dance's angle away from vertical shows the angle the actual location is

away from the sun, and the length of time the bee wiggles her butt

shows how far away the site is. Using this data, I was able to

tell that our bees had only found one good site so far, and that it was

two miles away to the southwest --- definitely not my swarm trap.

This all sounds a bit

esoteric, but the truth is that once you have a swarm in front of you,

waggle dances are extremely obvious and easy to decipher. After

only a few seconds of observation, I was able to find two workers

dancing about the same location, which I videoed above. The

dance's angle away from vertical shows the angle the actual location is

away from the sun, and the length of time the bee wiggles her butt

shows how far away the site is. Using this data, I was able to

tell that our bees had only found one good site so far, and that it was

two miles away to the southwest --- definitely not my swarm trap.

My first thought was to

set up a potential hive on the other side of the yard, smear it with

lemon balm, and hope my bees would find the site. Then I changed

my mind and figured I'd set up the potential hive much closer to the

swarm tree to ensure the bees found it. But half an hour of

observation showed that only one worker checked out the empty hive, and

she didn't even think it was worth crawling inside. (Scouts

looking for potential house sites go inside and measure the cavity

volume to ensure the hive is what they're looking for. When

visiting a good site, they'll spend over half an hour buzzing around to

check out the cavity from all directions.)

If we were going to lose

the swarm otherwise, it seemed worthwhile to try to catch it.

Huckleberry told me to lay out a white sheet underneath the swarm and

then cut down the tree to drive the swarm into a box (although I think

our spoiled cat might have mostly been thinking about napping in the

shade), but I got scared and called my beekeeping mentor (aka our

movie-star neighbor). More on the ensuing action in tomorrow's

post....

Want more in-depth information? Browse through our books.

Or explore more posts by date or by subject.

About us: Anna Hess and Mark Hamilton spent over a decade living self-sufficiently in the mountains of Virginia before moving north to start over from scratch in the foothills of Ohio. They've experimented with permaculture, no-till gardening, trailersteading, home-based microbusinesses and much more, writing about their adventures in both blogs and books.

Want to be notified when new comments are posted on this page? Click on the RSS button after you add a comment to subscribe to the comment feed, or simply check the box beside "email replies to me" while writing your comment.

It blows my mind that 1. You were able to decipher the bee dances to see that they did not seem interested in your swarm trap hive 2. You were able to explain it to us what the wiggle dances mean and how to decipher them

Honestly, I am gob-smacked in a very pleasant way. Thanks!

When a hive swarms, I thought it was because of multiple queens. Do you still have a queen in the original hive?

Is there any kind of pheromone attractant that you could place in the swarm catcher?

Gerry --- There are two times when a hive will swarm. After they decide they want to swarm, the hive produces a lot of queen cells (which are full of baby queens), and as soon as those are mature enough that they get capped (a week before the baby queens emerge), the old queen leaves with a lot of the workers. If you want to get technical, that's the prime swarm, which is what we have.

A week later, the queens start popping out. If the hive is only moderately strong, the first queen will kill all the others and you won't get more swarms. But if the hive still has lots of workers and honey, the first queen to emerge will leave with yet more workers, in what's called the bull swarm. The next queen to emerge again assesses the state of the hive (or, rather, the remaining workers do), and she might leave too with a much smaller swarm. Eventually, one of these new queens is the keeper, and kills her remaining siblings. These later swarms (which we could see next week) are smaller and not as likely to build up enough to survive the winter, although they might.

So, to answer your question, I have multiple queens in the old hive, but none of them are running around yet.

We have ordered lemongrass oil, which mimics the pheremone workers use when they find a new house site, for our swarm traps, but it hasn't arrived yet.... You can also order more expensive chemicals that are the actual pheremones, but reports say they don't work any better than the cheaper lemongrass oil.